13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

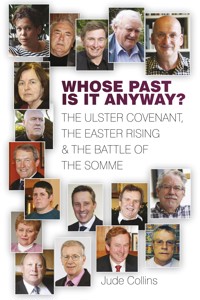

Ireland is on the cusp of what has become known as the 'Decade of Centenaries'. In this unique book, we gain an insight into three of these centenaries – the signing of the Ulster Covenant, the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme – from across the spectrum of political allegiances and perspectives. Including interviews with An Taoiseach Enda Kenny, Fr Brian D'Arcy, Niall O'Dowd and Roddy Doyle amongst many others, this collection of discussions touches upon the ethereal nature of our history, and the constantly shifting sands upon which we build our shared past. But what emerges as a consistent theme throughout these conversations is the degree of understanding that can be offered for our future in reflecting on how these events continue to shape our reality.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

To – who else? – Maureen, Phoebe, Patrick, Matt and Hugh

‘There are two tragedies in life. One is to lose your heart’s desire. The other is to gain it.’ George Bernard Shaw

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

Eoghan Harris

Danny Morrison

Enda Kenny

Jim Allister

Brian Leeson

Tim Pat Coogan

Niall O’Dowd

Davy Adams

Owen Paterson

Robert Ballagh

Ian Paisley Jr

Roddy Doyle

Nuala O’Loan

Mary Lou McDonald

Gregory Campbell

Fr Brian D’Arcy

Bernadette McAliskey

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

In one way, marking centenaries makes little sense. Why one hundred? We could as easily focus on a 99th or a 101st anniversary, and with as much validity. Even on a personal level, the singling out of particular events for anniversary attention – your birthday, my wedding day, the date of someone’s death – is odd. But maybe understandable. We humans feel a need to impose shape on experience, to link the past with the present, to look for pointers that help us understand what has happened and what significance we should attach to it. Without an anniversary to mark an event, there’s a danger it could become blurred or lost in the thicket of other happenings, that danger increasing with the passage of time. And so we choose particular points, erect milestones on the road that tell us where we were and who we are.

Ireland, in 2012, is entering into what some have called ‘the decade of centenaries’. There are a lot of them: the Ulster Covenant, the Dublin Lock-out, the Larne gun-running, the Howth gun-running, the First World War, the Easter Rising, the Tan War, the Truce, the Civil War, partition. Each of these events makes its own contribution to our history, and each relates to the others, not just through proximity in time, but because it builds on or reacts against others.

This book takes three of these centenaries for consideration. The Ulster Covenant saw the unionist people in Ulster solemnly commit themselves to all measures to block the passage of the London Government’s Home Rule Bill. Randolph Churchill encouraged them in their stand, declaring that ‘the Orange card would be the one to play’. And so it proved. Then came 1914, and the Ulster Volunteers, established to resist Britain’s Home Rule intentions for Ireland, marched in support of Britain to the carnage of the Somme – as did thousands of Irishmen from the south. The third centenary looked at here, Easter 1916, is the seminal event of modern Irish republicanism. From its apparent failure came a measure of Irish independence, with the creation in 1922 of a twenty-six-county Free State.

History, we’re told, is written by the victors. The interviews in this book are with people of different political allegiances who see our shared history differently. Some approach the centenaries with caution or even apprehension, fearing the possibility of deepened division in Ireland; more see the potential of these commemorations to speak to our present situation and add to our understanding. Some believe these centenaries should be occasions for the honouring of the dead; others argue for reflection on the events, in the belief that new meanings for today may be found in what happened 100 years ago.

In a few interviews, one can detect a suspicion that commemorations may be manipulated. Jim Allister cautions against the possibility that the centenaries of these three events will be seized by different factions and ownership claimed, because they fear that otherwise the contrast with their own actions – or inaction – might become too glaring. Others, like Mary Lou McDonald, see the centenaries as an opportunity for joint commemoration. Others again, notably Ian Paisley Jr, stress the need to see each event in its historical context.

Granted that we owe a debt to the past, does the meaning of that past change with the passage of time? A recurrent theme among those interviewed was the degree of understanding the past might offer the present, and the extent to which the past shapes our future. Bernadette McAliskey is alert to the danger that the present may become prisoner to the past and is robust in her challenge of such confinement. Other interviewees remark on the need to interrogate the past in order to understand it anew; time changes the meaning events have for us, but only when we are prepared to question them closely. Common sense tells us that our generation sees events from a more distant vantage point than those who participated in them, and this can show what happened in a different light. Some interviewees avoid this kind of emphasis. They believe our debt to the past is a straightforward one: these were people who performed great deeds and it is fitting we recognise with gratitude what has been done for us. Roddy Doyle, in contrast, calls for a humanising of the figures from the past: we must learn to see the mighty dead as mortal beings like ourselves, not as mythic figures.

Few of the interviewees, with the exception of Eoghan Harris, offer much in the way of commemoration specifics. Where it occurs, it is more usually in a negative form: we must avoid any militarisation or triumphalism in our celebrations, for example. Harris outlines a number of practical schemes which he believes would allow people from the north to become more familiar with those from the south and vice versa – a sort of mass education programme. Harris is particularly emphatic on the role of television in commemoration and urges government intervention, north and south, so that this may happen in an effective manner.

The reader may be surprised by the level of optimism in this book. Different political traditions may lay claim to different centenaries, but most interviewees look forward in hope, believing these occasions will provide opportunities in which understanding outweighs any possible danger. None of those interviewed believed that the centenaries need drag us back to the conflict from which Ireland has lately emerged. The belief is rather that the centenaries offer a chance for fresh thinking about the past and what it says to us.

My sincere thanks to all those who contributed so generously of their time in the composition of this book. It is my hope that the views expressed here will provide a stimulus for discussion and debate in the coming days and years, and that the distinguishing features of that debate will be honesty and respect.

Jude Collins

March 2012

EOGHAN HARRIS

Eoghan Harris is a journalist, columnist and political commentator. He currently writes for the Sunday Independent. He was a member of Seanad Éireann from 2007 to 2011, having been nominated by the An Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern.

Background

The house I grew up in was probably the most political house in Ireland – none of my friends had a house like that. My grandfather would visit every Sunday. He’d been an intelligence officer in the First Cork Brigade, and had been out in 1916, but more important than that, he was older than most of the Irish Volunteers in Cork. He had been a founding member of the Gaelic League in Cork with Terence McSwiney and MacCurtain, and MacCurtain was a very close friend of his. He didn’t have that much time for McSwiney; he thought he was a bit of a wimp, to be straight about it. He hated both the Free State and de Valera indiscriminately.

He was a solicitor’s clerk and they held onto him after 1916 pretty well, but his eyesight came against him. There were jobs in Cork Corporation given to fellahs with disabilities, but he couldn’t get one because he wouldn’t take the oath of allegiance. Then when de Valera came in, he hated de Valera as well, so he remained a kind of intransigent republican.

My father was more of a communist. He tried to get to Spain to fight in the civil war. He started a small business, but he remained a very hard-line radical republican and so it was inevitable that I would gravitate towards Sinn Féin.

In our house they talked non-stop. And it was detailed, hard-core stuff. Growing up I knew a lot of the Cork republicans who had been in the Coventry bombing campaign and that kind of thing – Jim Savage, Jim Donovan who was an explosives officer. Cork was full of former hardcore republicans.

When I was at university, I didn’t spend much time in college; I spent most of my time downtown, and the Wolfe Tone Society in Dublin got in touch with us. We didn’t know much about them. Roy Johnston came down once, and myself and Dáithí Ó Conaill, who later became chief-of-staff of the Provos, started a Wolfe Tone Society in Cork. We used to meet in the Father Mathew Hall, and on a wet night, when things were slow, there were only about seven of us there. There were two girls that I think we were half-interested in. On a slow night, the girls would ask Ó Conaill to show his back. He would do so reluctantly, but if we were stuck or bored, having had our meeting, he would take off his shirt. Down along his back were stitched the Sten gun bullets he had received on the northern raid. It was like a nightmare of a back, and how he breathed I don’t know.

I liked Ó Conaill a lot; I got on very well with him. Our first activity was to plant flowers on the Western Road in Cork, to beautify the environs of the city coming in. We wanted to do something civic, and we set up a flower co-operative, which has flourished ever since.

But my first big march or demo: the Earl of Rosse was visiting Cork, and Barry took it into his head that he was somehow connected with an event in the War of Independence – he was very vague about it. Barry was wrong but I didn’t care. Rosse was coming to Cork, and Barry had denounced the visit and called upon the people to boycott Rosse’s visit to the Cork Choral Festival, as it was. Nobody took a bit of notice of Barry – he was old at that time and nearly blind. He lived in a flat above a beautiful part of Patrick Street; he could look down the Grand Parade and look up Patrick Street, so he could see the whole traffic of the city passing. And he called for a boycott. I don’t know – I felt that I somehow owed him. I was a very good organiser and I organised the biggest march ever from UCC, of almost the entire student body – 98 per cent. It was done in total silence. We marched in fours past Barry’s flat and he waved to us from the window as we made our way to City Hall.

I was sent up to Maghera, to one of the founding movements of the civil rights organisation. I was sent up because Roy Johnston had a terrible stutter and Tony Coughlan had written this document about the civil rights movement, and I was up there to drive Goulding when he wouldn’t drive himself. The meeting was in Kevin Agnew’s farmhouse. The northern command of the IRA were all there – Liam McMillen and McBirney from Belfast, Jim Sullivan from Belfast, and a whole lot more – and Francie Donnelly from the border. Then there was a big contingent of representatives from the communist party – I don’t know if Fred Heatley was there but Betty Sinclair was. And they all read this document from Coughlan, which fundamentally was the organisational document of the civil rights movement.

So we started a series of peaceful marches. I remember the famous phrase in it that I had to read out, ‘This whole strategy will fall apart at the first sound of a bomb or a bullet.’ They didn’t see that there could be other eventualities apart from that, such as maybe having civil rights marches broken up forcibly by other means.

Certainly after Bloody Sunday I was in a very militant mood and I can’t honestly say that I had any warm feelings for the British Army. I didn’t, however, believe in an insurrection or armed struggle, because I didn’t believe it was practical. I feared all sorts of things – that the border would be redrawn or something. In 1970, my whole reaction was, ‘Don’t let it happen down here, try and calm this situation down.’ Then as the situation went along, in 1971 and 1972, I fell very much under the thinking of Conor Cruise O’Brien. We had our disagreements – I always remained a bit more republican – but fundamentally I agreed with him that the southern state had never faced the northern question fully and never understood it, and never really understood either the unionists or the nationalists. I said, ‘What are we messing around with this for? We’ve no business dabbling in this.’

My position hardened over the years until finally, I suppose … I never was a two-nationist, but certainly I regard the northern settlement as the least of all evils. I didn’t regard it as a good settlement, nor do I regard the current settlement in Northern Ireland as a very stable one, but I regarded it as the least of all possible evils and I wanted to keep the Republic away from all this stuff, because I thought the Republic was full of shit about Northern Ireland. If they were going to invade or they wanted a united country, they’d have to arm and prepare for it properly. They’d never done that, they just engaged in armchair rhetoric.

I describe myself as a revisionist republican. When I say that the state in the north is unstable, I don’t think it’ll disintegrate into violence or chaos. I mean not stable in the sense that it will evolve; it’s not a permanent political settlement in my view. And I hope it will evolve towards a united Ireland, towards a federal Ireland. That’s my position on it.

The Centenaries

I think the centenaries will receive a lot of public attention. I should point out that from 1966 onwards to the 1970s, and the split taking place, my thinking began to change very strongly. I became slowly but relentlessly very anti-nationalist. I feared a spilling of the northern conflict over the border and the Irish Army getting involved. And far from being sanguine about that, I thought the simple truth was that they’d get the shit kicked out of them – that’s what bothered me. My fear was that there’d be a war, a civil war, and that we would lose! The Republic’s Army wasn’t up to that kind of stuff, nor the IRA. I just thought it was a very stupid kind of notion.

I regard the Ulster Covenant of 1912 as fundamentally a delinquent political act, like I regard the 1916 Rising as a delinquent political act. I regard both of these – and these are foundation events – as fundamentally very problematic. Now they’re completely different to the Somme or the 1913 Lock-out. There are a lot of people trying to get in on these centenaries. The fact is 1912 and 1916 are mirror images of each other. Nineteen sixteen, in my view, was a reaction to the 1912 Covenant in many ways. It was what I call a delusionary reaction; Pearse and that bullshit about, you know, if the Ulstermen have guns in their hands, we should have guns in our hands – all that sort of rhetoric. Not understanding that Northern Ireland has a very intractable problem of a million unionists who are not to be budged.

Now the reason I call the Ulster Covenant a delinquent act is because if Carson believed that he had to defy a parliamentary majority in Westminster, he was actually defying the constitution of the United Kingdom. Then he should have had the courage to go the distance. It was a treasonous act, the Covenant, by the way. If Carson was going to go for treason, then he should have had the courage of his convictions and gone for independence. He should have gone for UDI like Ian Smith, because that was the logic of his position.

I’m not one of these people who share any admiration for Carson. I had admiration for Craig, who I thought was a pragmatist, but I thought Carson was very like Pearse in the kind of delusionary rhetoric he engaged in. For example, he admitted years later that they should have accepted the first Gladstone Home Rule Bill. He wasn’t a partitionist, he mourned the fact that the country was divided; he knew it was an appalling settlement to end up with an appalling 40 per cent Roman Catholic minority. This was no basis for a permanent and stable state. So he knew it in later life and he acted in bad faith in 1912. He fundamentally brought people out in what was the first act in a war of independence to set up a sovereign state of some sort, and hadn’t the guts to carry it through. He wanted the best of both worlds. That dichotomy – the dialectic between a quasi-constitutional position on the part of unionism, married to this extreme kind of pro-union rhetoric – was a total contradiction. There’s a whole tradition in unionism that at one and the same time is radical and resistant – it’s Calvinist republicanism. It’s anti-the United Kingdom, anti-being told to do anything, and not really accepting of the rule of law and the monarch. And then that’s matched with an excessive rhetoric on behalf of the monarchy. I think unionism has never worked this out for itself intellectually and it needs to do so.

So I don’t know how the Covenant centenary will be presented. I think what happened was that Wolfe Tone had a very benign and generally pluralist view of how republicanism would go but it was deeply distorted by a Unitarian, John Mitchel. It was John Mitchel who brought this very vicious physical force and almost hysterical sectarian edge into it, even though he was a Unitarian and from the Protestant tradition. He brought a kind of Calvinism into republicanism – all this, ‘If I could grasp the flames of hell in my hand and hurl them in the face of my country’s enemies’ – and then he went off to become a slaver in the southern states. I regard Mitchel as a very inauthentic person. I was very sorry that Pearse took up that kind of republicanism, which was delusionary and abstract compared to Wolfe Tone’s republicanism. Pearse was in a big tradition of European romanticism at the time, like a whole kind of fevered, delusionary nationalism. That somehow you could have an insurrection in Dublin and somehow the Orangemen would join it or help you. Then to think he could take German aid and there’d be no consequences to it. I regard the whole of 1916 as a very delinquent act. Mary McAleese says the men of 1916 were heroes. Well then, what does that make members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police? Ordinary lads from working-class districts who joined the police and suddenly someone comes up and shoots them in the head.

I think 1916 is very problematic and the legacy is particularly problematic – the legacy of 1916 in the Republic. In 1921, we signed the Treaty. Fine, if we signed the Treaty and let it go at that, and ran our state. But we engaged in this rhetoric, leading northern nationalists to believe that somehow we were going to do something for them if they did something. And when they did something, we didn’t do anything for them. I think the Republic, the Free State, right up to the rhetoric of the 1966 anniversary, which I remember being on RTÉ at the time, is a very inauthentic tradition. And I think the Republic has no right to parade troops past the GPO without accepting that it’s a very problematical tradition, that first of all it was a putsch, it was an attempted coup. Pearse and the others didn’t have the support of the public. They got it retrospectively, but at the time, democratically, it was a coup. I have never found any logical or rational way to extol and hail the 1916 men and condemn any other group of republicans that followed them into a coup.

One of the candidates in the presidential election, who suffered at the hands of Martin McGuinness on the famous Frontline programme, Sean Gallagher, said at one stage he hoped it wasn’t all going to be military pomp and ceremony, although he didn’t follow up on that. If Enda Kenny proposes to march the Irish Army past the GPO and to go into the whole 1916 rhetoric, then he should not be surprised if young men who are coming up to sixteen or seventeen years of age start pondering introspectively things like Ireland, united Ireland, nationalism, Pearse and all the boys, what were they fighting for, whatever. Where is all this going to go?

I don’t think that happened in 1966 but I think that was an accident of history. In 1966, we were going through a huge revolution. I call it the ‘American revolution’. It was a huge sexual and political revolution. There was a big sexual revolution going on, about the Church and about contraception and divorce, and the American civil rights movement rolled over it. And we were coming out of a recession, so there was money around.

The dramas of 1916 depicted in 1966 may have marginally affected young people, but not so much in the Republic of Ireland. I think centenaries generally are very problematical. I remember my grandfather telling me that the 1798 commemoration was the one that brought him into the movement. He joined the IRB, he helped to put up a statue on the Grand Parade, he was on the committee, and from the committee he met members of the IRB and they swore him in. From there he joined the Irish Volunteers. He said that the 1798 commemorations radicalised the young men of Cork.

One hope is that the peace process will be bedded down a bit better by 2016, but I would question any military display by the Republic, with Enda Kenny taking ownership of not just 1916 but what I call the cult of Michael Collins, whereby Fine Gael, which is fundamentally a peaceful constitutional party, takes an inordinate and inappropriate interest in Collins the gunman. They’re quite prepared to celebrate Collins on Bloody Sunday shooting a lot of British agents in the head, but I doubt if they would publicly endorse any other group of the IRA shooting anybody in the head in any other part of the island. There’s a fundamental hypocrisy and contradiction built into the Republic in its position on 1916.

How should those events be commemorated? I’ve been thinking about that a lot and the passions that might be inflamed by certain kinds of marching, certain kinds of commemoration. I think there’s a great need for the Northern Assembly and the Dáil to get together and set up a kind of parliamentary body that would do its best to influence how both 1912 and 1916 would be commemorated. Now nobody’s saying that would be easy, but I regard the Ulster Covenant and 1916 as being twin foundation acts. It’s not quite the same thing with the Ulster Covenant, because there’s not going to be a British Government endorsing that celebration, but obviously the majority unionist tradition will want to endorse it in some way. I think the time has come to get together a parliamentary body to consider how this whole thing is to be dealt with. The Somme has to be dealt with as part of it, because for me the Somme, despite the horror of it, represents a somewhat benign tradition, a chance to actually talk and bring the two traditions together, because of the common sufferings.

It was absolutely disgraceful, the way the south suppressed the issue, up until recently when the Queen of England visited Islandbridge. I was with a lot of old veterans from the Second World War, from all over Ireland, and they were telling me appalling stories of trying to celebrate. A couple of men in Sligo town were not able to get the FCA to parade to do the military honours because Fianna Fáil or Willie O’Dea or the Ministry of Defence was afraid it might reflect badly on him. There’s a lot of foot dragging goes on in these things.

But to go back to 1912, I think we need an all-party parliamentary committee to look at how to commemorate that whole period, to consider it almost as one period of events and to look at the totality. And in looking at the totality, I think you’re talking almost entirely about television. It’s the only medium that actually has the power to deal with this. That means that BBC Northern Ireland and RTÉ should actually be instructed – I mean it’d not be a matter of freedom – by the parliaments of both states on how to go about the commemoration. They can do their own thing separate from that, but there should be a minimum that both parliaments insist upon. Now this would take some working up, but we’ve the time to do it.

For example, they need to show programmes that show the problematical side of 1912. In other words, an appropriate unionist producer should be able to do his bit. If the DUP or the UUP want to make a programme about how wonderful it all was, they should be given the facilities to do it, and expert teams. Then someone from an alternative tradition, who doesn’t agree with that, who believes, like me, that it was a delinquent act that was full of problems – like why Carson didn’t follow through, why he was going around saying he should have accepted the first Home Rule Bill, why in later life he regretted that he’d set up a state with a 40 per cent Catholic minority, which was inherently unstable – needs to make a documentary showing that point of view. I’d like to see a lot of deliberately antagonistic programmes, being transmitted simultaneously by BBC, UTV and the Republic’s television – and they should be pretty well simultaneous transmissions, so people would have to turn over to Sky to get away from it! [Laughs] I mean that the period would be block-booked for a week or so – a week of commemorations – and you’d have films on 1912 and you’d have films on 1916. Unionists should be invited to make a film on 1916 from their perspective. Northern nationalists or a nationalist grouping should be allowed to make a film showing how they saw 1916-21 as an act of betrayal, almost, of their tradition, with what happened with the Boundary Commission. They should be allowed to put their point of view across. And the Republic should be able to make its constitutional Michael Collins case. In other words, I’d like to see a series where there’d be alternative viewpoints; beautifully produced to the highest production values and with plenty of money spent on it. That’s one element of what I call the commemorations.

The second thing I’d like to see done between Northern Ireland and the Republic is something like Pierre Trudeau’s Immersion in French course in Canada, where people had to learn French. I think there should be immersion courses, the equivalent of the Coláistí Samhraidh, the summer courses colleges in Ireland, whereby people from the unionist tradition, northern unionists, would be encouraged to come down, or send their sons and daughters down, for an immersion course of six months to a year, which would be properly funded and have a proper reward system, like college subsistence, etc., attached to it, at a university of their choice. I’d like to see a hundred to two hundred northern students in the Republic doing Irish Studies courses in an immersion, living with Irish families, and the reverse happening in Northern Ireland.

Education is a boring word but education is key to this. I’m talking about education – mass education – with these television documentaries. I’m talking about education at the primary-school level, that there be these exchanges in what I call ‘Irish Studies Immersion Courses’. Sending an Irish family up to live in the Glens of Antrim, to live the ordinary lives of people and hear the traditions of Orangeism, attend their local Orange hall, listen to unionist historians and northern Protestant historians putting their point of view. You’d want to send a group of them, so they wouldn’t feel isolated or that they were being brainwashed, but this immersion in Irish Studies – in the broadest sense of Irish Studies, which includes the northern tradition as well – I’d like to see that go on.

And the third thing I’d like to see is the beginning of mass travel. This has got nothing to do with the unionists at all; it’s equally true of northern nationalists – I’d like to see more travel between Northern Ireland and the Republic, and vice versa. Therefore I’d like to see heavily subsidised holidays at a mass level, in which a couple of thousand people a year could take a holiday in Larne or take a holiday in the Glens of Antrim. And that people from the Shankill would be able to come down and have a decent holiday in rural Ireland, in an environment where there’s a group of them, and everything would be laid on properly for them. If we designated a year for it, that sort of stuff would go on throughout the entire year.

I think that once you open a mind a little bit, there’s no stopping it. I think change is inevitable. I always like to quote John Bruton: he gave a lecture and said that the nationalist tradition in the Republic should have opened itself more fully, opened its eyes to the reality of the unionist presence on the island; but likewise the unionists had an obligation to ask themselves, throughout the Troubles and before, if the Republic weren’t better friends of theirs, in many ways, than Britain? To put it brutally, what he implied was that all the British governments, fundamentally regard Dean Swift and the Irish Protestants in the eighteenth century, as the hunchbacks of the tower – a nuisance to be kept quiet, to be thrown a few baubles. He said unionism should reflect how many friends they had in the Irish Republic, both in government, in terms of its actions, and in people like Conor Cruise O’Brien and others – poets and writers – who upheld their democratic rights. ‘Would they not reflect on this?’ he said. I strongly believe that locking the unionist and nationalist traditions into this cockpit in Northern Ireland – it’s like a cauldron. Despite the merits of the peace process and of the Good Friday Agreement, there’s been no shift in sectarianism, no real shift. This is what preoccupies me. I’m always abused for being revisionist and anti-nationalist, but I think I take a deeper interest. I read all the papers in Northern Ireland, and it seems to me not much has changed. I mean there’s the surface patina, but fundamentally the old tribal animosities are there.