7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Unicorn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

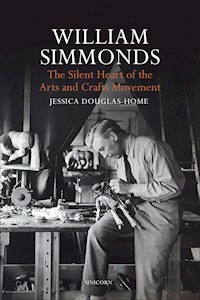

This book uncovers the work of sculptor William Simmonds, one of the forgotten originals of the Arts and Crafts movement. Inspired by his pastoral surroundings in the Cotswolds, he played a particularly vital role in the movement between the two world wars. After the First World War Simmonds emerged as a master of woodcarving, known for his exquisite oak, pine, ebony and ivory carvings of wild and domestic creatures. He earned his living by making puppets and became Europe's most renowned puppet master. His wife Eve, a well-known embroiderer in her own right, made the puppets' costumes and accompanied the puppet shows on the spinet, playing early music discovered by Dolmetsch and pieces by Cecil Sharp and Vaughan Williams. Simmonds's circle included the artists William Rothenstein, Edwin Abbey, John Singer Sargent and E.H. Shepard; architects Ernest Gimson, Detmar Blow, and the Barnsley brothers; potters and stained-glass artists Alfred and Louise Powell and Edward Payne; and textile printers Barron and Larcher. Poets Tagore, W.H. Davies, John Masefield and John Drinkwater; writers Max Beerbohm and D.H. Lawrence; and the musicians Lionel Tertis and Violet Gordon Woodhouse with her 'four husbands' all played their part. This book documents that lost world and adds another dimension to the story of the extraordinary Violet Gordon-Wodehouse, who lived at Nether Lypiatt Manor a mile from Simmonds's cottage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

WILLIAM SIMMONDS

The Silent Heart of the Arts and Crafts Movement

JESSICA DOUGLAS-HOME

Contents

Prologue

When I was six, my father inherited a house in the Cotswolds, Nether Lypiatt Manor, from his aunt, the musician Violet Gordon Woodhouse. Its interior had been kept entirely unchanged, exactly as she had left it, like a shrine to Violet’s memory. On entering the front door for the first time, my eyes lit on animals settled happily on cushions on the drawing- and sitting-room floors: a cat stretched its claws to play with a marble, another bunched up by the fire slept peacefully; a Pekinese gazed soulfully upwards with jet-black eyes (see plate 23); and under the harpsichord there was a hedgehog which, if prodded, waddled along from side to side. All these, I was told later, were carvings by Violet’s close friend, the sculptor and puppetmaster William Simmonds.

Other smaller objects were housed in glass cabinets. I found a tiny ivory duck, an inch long, and a wren sitting on a chestnut-tree leaf painted in gilt. The most intriguing was a 22-inch high puppet of the Archangel Gabriel (see plate 25). The locks that crowned his head were flicks of curly wood shavings, framing intense, happy eyes of deep blue. His mouth was open, as if he were singing to the heavenly multitude; his body was clothed in a tight-fitting garment made of little leather flaps cut like leaves; his wooden wings could be stretched out to a span of almost three feet. Apart from his face, what struck me most was the detail of the carving: the delicacy of the hands and fingers, the feet and toes. Decades later, when I understood more of William Simmonds’s character, this puppet seemed like an unwitting self-portrait. Music and song were as much part of his life as his sculpture.

I used to think it was my mother who led me to become a painter. Lonely in smog-ridden London, where I was taken after my parents’ divorce, she gave me a box of charcoal sticks with which to draw. I experimented with thick lines, shading and smudging with cloth or fingers. I was excited and somehow liberated by this new method of drawing. But now, as I look further back, I think it must have been my father who started me on the track, with more purpose.

Hedgehog, designed to amble along when gently pushed

Cat with Marble that permanently settled on the carpet in the Nether Lypiatt Manor’s drawing room

One late morning in the heat of an early summer sun, he announced we were off for a ‘ten-minute drive’ to the Simmondses’ cottage, The Frith, in Far Oakridge. We left the car on a verge in a lane, scrambled out and pushed through a small gate into a steep field, leaving behind us hedges of roses and honeysuckle, foxglove, bramble and rabbits. As I padded behind my father down the narrow path, I met a head-high wall of ripening green meadow grasses, big as a forest, green as a moving sea, stems supple and billowing in the summer breeze. Through gaps I saw more flowers: willow-herb, cinquefoil, moon daisies, speedwell, eyebright, pimpernel and pink orchid with spotted leaves – all these and others. My father loved flowers and taught me their names. But he would not let me run among them and pressed on – we were always late it seemed – pointing down at the house beyond and urging me with his strong voice and dark-eyed glance to ‘come along’.

There, halfway down the valley, on the edge of the hill stood a mottled grey stone house. It had a moss-covered tiled roof and a chimney, upright, steep and sharp as a child’s drawing. For no traceable reason the first sight of William Simmonds and his wife Eve in their garden, the memory of the sharp meadow grass about my chin and the moon daisies level with my eyes, has stayed with me since.

That morning I had my first lessons in drawing. I know this from William’s pocket diary, in which he had also recorded a far earlier encounter when my father, on leave from Special Operations in Greece towards the end of the war, had brought me to my great aunt Violet’s house. I was then a few days old, my brother aged two.

Drawing lessons with William became a central part of my childhood. His studio in the barn was a world apart: a wounded owl discovered in the woods, perched recovering in the rafters; there was a magnificent workbench, and near the wall a crowd of puppets clipped on to a line of rope. But William had long stopped performing in the barn; it was in The Frith’s sitting room that my brother and I saw the dolls at work. Each school holidays, spring, summer and winter, I would be dropped off to draw with William in the garden, in the fields or, if it was raining, in his studio. Without spelling it out, he conveyed the message that nothing could be achieved without a visual language, which meant a proper study in drawing. Charcoal was a beautiful medium in a dexterous hand, he said, but more adaptable to mass blocks and shapes than to line drawing. To mark the end of our sessions, Eve would look in, remark charmingly on what I had done, and summon us back to the house for scones with jam and cream.

William was convinced that, to be a true artist, inspiration is not enough: there must always be a properly developed craftsmanship. He went through eight years of training, according to a method that originated with the French atelier and the German artists’ guilds, and which had evolved over centuries. This practice had produced some of the great artists of our civilisation, as well as those unassuming artists like William, whose work neither professes to rival the works of genius nor fears the challenge of perfection. William was one of the last graduates of a method that was able to develop natural gifts into a disciplined artistic identity. He became a master of anatomy, science, woodcarving, plaster-modelling, stone carving, watercolours, canvas-preparation and oil painting. He learned all the traditional crafts including the art of mixing his own pigments, plaster-cast drawing and drawing from life.

This exacting training of hand, eye and mind, far from being a constraint on creativity, endowed him with both competence and the freedom to exercise it. He was convinced ever afterwards that true discipline is also a liberation, and that artistic licence without skill leads only to anarchic repetition. In addition to absorbing all those practical skills, he was able to enjoy the benefits of attending weekly lectures on ancient and medieval European art, and on the art and literature of the civilisations of Egypt, Greece and Rome.

In the decades that followed the First World War, William’s puppets gathered a cult following – their design, songs, words, sets and music all his own creation. Many leading musicians, writers, theatre directors, poets, critics and politicians of the day were spellbound by them, such as the Suffragette and composer Ethel Smyth, Bernard Shaw, John Masefield, Thomas Hardy and Winston Churchill. So, too, were local villagers and children from all over the English countryside – all succumbed to their charm, although ‘charm’ would be too platitudinous a term for Ethel Smyth, who wrote to William about the ‘strange haunting absolutely unique impression your art leaves in one’s life … as for “The Woodland” … I long dreadfully to see that scene again’.

But all this was of secondary importance to William; it was his serious sculpture above all that really mattered to him, and where his true genius lay. He worked slowly. Early in his career he acquired a following of serious art collectors, museums and patrons who snapped up everything he could produce. As a result his work seldom came on the market. In 2017 two pieces appeared in the saleroom: the collectors and cognoscenti of the Arts and Crafts world entered a bidding war, proof of Simmonds’s enduring achievement as an artist.

CHAPTER 1

Beginnings

1876–1892

‘William’s father released him, enabling William to take up a scholarship at London’s National Art Training School.’

William Simmonds was the son of John Simmonds, a poor builder who started life in the tiny hamlet of Eton Wick on the outskirts of Windsor, eventually becoming a respected District Councillor of Works. Like many who rise to fame in later life, William romanticised his childhood, attributing to his parents a situation rather more elevated than they had in fact enjoyed. John had lost his own parents at a young age and had been forced to support his three sisters and younger brother by working in the pub that his parents had run, the Grapes Beer House. He also worked as a carpenter and, thanks to this skill, was able to obtain a position in Windsor Castle’s Office of Works. His chance for promotion came in 1872 when the castle’s resident architect, John Lessels, asked him to help him survey and reconstruct the British Embassy in Turkey, in Constantinople’s Galata district, on the European side of the Golden Horn. It was the second time that century that the British Embassy had gone up in flames.

Lessels’s choice of an inexperienced 26-year-old carpenter was risky but inspired. John was an able draughtsman and proved resourceful, determined, industrious and full of artistic talent (the Royal Archives have an accomplished Simmonds drawing of buildings inside the precincts of the castle). Lessels, still negotiating his own contract’s terms, would arrive later in the year, leaving John to undertake the preparatory work single-handed. Living expenses were to be covered by the Embassy and John calculated that within a year he could save enough to get married. He was leaving behind his sweetheart, Martha Walker, a London girl, stalwart and sensible. She had promised to wait.

John set out in January 1872 on the SS Timsah to take on the role of Assistant Clerk to the Office of Works. It was a far larger job than his title and slender salary suggested. Besides the Embassy mansion, he would be supervising the rebuilding in stone of the English Church at Kadiköy, the British Seamen’s Hospital and Institute, the British Consular building, the Ambassador’s Residence, the coach house at Tarabya, the post office and the Jewesses’ College in Galata. Much of the old Ottoman city had been transformed two decades earlier into a relatively modern metropolis, but in its heart it remained a medieval labyrinth. The houses were virtually all built of wood and the city was constantly ravaged by fire.

Unprepared for the fierce intensity of the summer heat, he found the twelve-hour working day exhausting and in July went down with a fever. He recovered in five days and from then on allowed himself a day off a week; after that, as if inoculated, he was never ill again.

As a member of the Embassy staff, he went to most of the official national parties from the staid American Feast Day to the exotic Greek one with its regatta on the Sea of Marmara and the Islamic bayram for which mosques were illuminated all over the city. He went on expeditions, to see the Sultan’s new mosque, an eclectic mix of different styles, built for the Sultan’s mother in Aksaray, to sketch the Galata Tower on the hill below the Embassy or to bathe in the Marmara. Constantinople’s vivid cosmopolitan world opened up before him. He took lessons in Turkish, bought a French dictionary (the city had a large French-speaking community), and began recording the ancient city’s way of life and its minutest architectural details.

When news came that Lessels was arriving by ship with a Captain Galton on 30 September, John, who was becoming a hard taskmaster, pressed his men in the August heat. He finished a sketch for the Porter’s Lodge. Large deliveries of cement were ordered – 100 caskets for the post office, the Embassy and the British Seamen’s Hospital.

The day after Lessels’s arrival, they were all on site. John orchestrated a tour of the Embassy and its outbuildings – stables, coach house, grooms’ quarters, the nearly completed servants’ hall – and Lessels made a final decision on the design for the Embassy’s grand staircase. More than content with John’s work, Lessels agreed to his request for a pay rise and returned to England in December, taking with him a letter from John proposing marriage to Martha.

William’s father, John Simmonds, was in charge of the restorations of the British Embassy in Constantinople after its destruction by fire in 1872

Although William encouraged his mother in old age to talk about life in Turkey, there are no details about her north London background nor how she and John actually met. Now twenty-three and a fiancée, the intrepid Martha Walker arrived in Constantinople on 13 September 1873. John took a small boat out into the Bosphorus to meet her ship, which, he found to his intense disappointment, had been put into quarantine for ten days. He would have to make the preparations for the wedding in two weeks’ time on his own – particularly trying since he and the rest of the Embassy staff had been enlisted for extra work: Queen Victoria’s second son, Prince Alfred, was due to stay en route for Russia. Having narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in Australia, he would need protection in Constantinople’s far more dangerous environment. John managed a half-day holiday to buy things on 26 September, dined that evening with a male colleague and the following morning married Martha in the Embassy chapel.

Martha settled in well enough, and was to some extent captivated by the glamour and colour of the city. But she never came to terms with Turkish brutality and mayhem. To the end of her life one incident remained vividly in her mind: crossing the Bosphorus with her friend in the Embassy, Mrs Meekins, she had noticed a strangely disquieting object beside their small boat. ‘Whatever is that large black thing in the water?’ she asked. Mrs Meekins told her to look away. There had been an attempted rising among the Greeks. Forty papaz, as the priests were called, suspected of leading the insurgence, had been taken out on the Bosphorus and beheaded. ‘And serve them right’, said the boatman.

Violence was so prevalent that John never let his wife out alone and hardly dared walk about the streets himself after dark; if he did, he made sure he carried a paper lantern (on sale in every street) with his pistol, so that he could see where he was shooting. It was certainly not the ideal place to have children but within a year Martha gave birth to a daughter Annie and, eighteen months later, on 3 March 1876, to William.

At the time of William’s birth, life in the city was becoming increasingly alarming. The previous year some Christian peasants in Herzegovina and Bosnia, two small mountainous provinces on the western front of Turkey’s Empire, had rebelled against their Muslim landlords and the Turkish Sultan Abdülaziz. By the spring of 1876 isolated skirmishes had turned into full-scale war, with vicious battles in the hills, woods and valleys of the region, and many dead. The disruption was felt in Turkey itself, with turmoil spreading to Constantinople.

Soon after William’s birth a blaze started close to the Embassy. As the flames came nearer and nearer Mrs Meekins said, ‘For God’s sake close the window’ as the curtains were floating out and sparks from the burning wood were beginning to settle on them. Years later, Martha described to William the sight of hundreds of burning houses and told him how, when a roof fell in 300 yards away and the sparks flew up, the eighteen-month-old Annie had clapped her hands and he had smiled in delight.

For all his promises of reform, the Sultan lost control as the revolt spread to Montenegro and soon to Serbia – an autonomous principality within the Empire – and Bulgaria. Abdülaziz had been on the throne for seventeen years. In 1867 he was the first Ottoman Sultan to visit Western Europe and his trip included a visit to the United Kingdom, where he was made a Knight of the Garter by Queen Victoria and shown a Royal Navy fleet review with Ismail of Egypt. Abdülaziz’s greatest achievement was to modernise the Ottoman Navy. But now public demonstrations forced him to flee from palace to palace with his vast harem and finally to surrender power to his nephew, who for four weeks had been locked in a cellar to acclimatise him to his new role. The Sultan, after ceding power to his nephew, is alleged to have committed suicide with a four-inch pair of scissors.

Constantinople’s Europeans now experienced the full blast of Mohammedan militancy against the Christian minority in Salonica. A Turkish Christian child was snatched from her village and forced to abjure her religion. Trying to secure her safety in a mosque, two of the most influential of the European diplomats – a French and a German consul – were brutally murdered, their bodies stamped on and their mouths stuffed with earth. Mercifully 1876 saw the completion of the Embassy project. The Simmondses were not going to extend their stay a minute longer than they had to. John packed up and was heading back to in Britain as soon as he could find a boat to take them.

It was not easy for John Simmonds to readjust to life in England. After a brief period with Martha’s mother in Middlesex, he decided to try his luck in Scotland. He moved the family to Edinburgh, where his mentor Lessels had had a thriving practice. John would have an introduction there and, he thought, better prospects of work than in England.

We do not know what went wrong, but within five years, despite his connections in Edinburgh, John was back at Eton Wick, where he rented a small cottage and re-established himself as a master builder. The family remained there throughout William and Annie’s early childhood. For William it was an idyll. To him it was the surrounding farms, woods and fields that really mattered. On the flat, undrained farmland, he messed about in the deep ponds with their rich wildlife. He helped milk and plough and bring in the harvest. Soon he was tacking up the farmers’ carthorses, feeding the pigs and milking the goats. He learnt the workmen’s folk melodies and their mildly suggestive pub songs.

Europeans near the British Embassy in Constantinople insulted in the streets during the Simmondses’ time in Turkey (1872–6)

John was not slow to notice his son’s affinity with the natural world. He gave him his old sketchbook and lent him pencils and crayons, and finally a paint box. By the time William was eight, he was out in the fields and meadows making detailed drawings: a sparrow’s nest on the knoll near the church, a hedgehog or a frog in the reeds of a stream. By the age of nine, he was mixing his own paints.

William’s first oil painting is a portrait of his pet guinea pig, painted with a skill and a humanity characteristic of the man to come. This much-loved creature, with its black, orange and white fur, snuffles within a bed of pristinely clean, sticklike straw. The straw was there for artistic effect only, for he lived indoors beside William day and night; William had house-trained him.

Ten years after returning from Turkey, having been promoted within the Urban District Council to Inspector of Factories, John moved from Eton Wick to Eton High Street, where he rented a house with a joiner’s office on the ground floor. The ten-year-old William was taken away from his rural life, but the family was moving up in the world and John had ambitions to found a family partnership. When William was thirteen, John put him to work with him in the afternoons and a year later employed him full-time.

By good fortune a decade earlier the Great Western Railway had sold a plot of land in Windsor to a committee of local philanthropists to build the Windsor and Eton Royal Albert Institute. Their aim was to meet the growing demand for education for the working classes and ‘to aid the pursuit of knowledge and art so loved by Prince Albert’.

Here William was allowed to attend evening drawing classes under the art teacher Charles Hollis, who recognised his talent. The institute gave William more than art classes. It had room for every kind of indoor recreation: a hall for music and for lectures, along with classrooms and a library. He lived in the library. The editor of the Eton and Windsor Express, Charles Knight, had been a local hero who had published plain, useful books without frills. William devoured the fine high-definition pictures in Knight’s Penny Magazine, moving on to Knight’s basic Cyclopaedia and his Cyclopaedia of Arts and Science. Later he discovered the historical novels by the local author, Margaret Oliphant. If his father could spare threepence, he would go to a Tuesday lecture – on parts of the world he had never heard of, or on Shakespeare or on ‘Folk Lore, Legends and Superstitions’; and there were concerts – here he heard for the first time the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan.

By the late 1880s the trustees and the headmaster saw the institute as part of a wider plan, a training ground for promising art students who in turn could become teachers in the new art schools being set up all over England. Hollis forged a close relationship with the Department of Science and Art in Kensington and encouraged selected pupils to sit an exam for the National Art Training School, with a County Council scholarship attached. Even though William could attend only two evenings a week, Hollis watched over his progress with particular care. No one, he thought, was a more worthy candidate to be helped to the next rung of the educational ladder.

Over the next two years, William grew into a good-looking, self-contained young man with evenly proportioned features and a serene expression. He was quiet and shy but determined. When he was sixteen, he asked to see his father for a formal meeting to discuss his future. Could he please be released from his apprenticeship in the Simmonds business? He would be sorry to leave the family, especially his sister Annie, to whom he was close and with whom he shared his love of art. Although the Simmonds practice was winning more District Council work, it had no artistic content – just contracts in surveying and sanitary inspection. Could he not enrol at a prestigious London art school, like the National Art Training School, with whom the Royal Albert Institute had a special connection? His teacher was urging him on. If he did well enough in the exam, he would not cost his father a penny. Not yet sure of his vocation, he argued that he would be given the opportunity to learn many disciplines, from which he could later choose. Whatever happened, he would at least end up qualified to earn a living as a teacher.

The hour-and-a-half entrance test was surprisingly easy. William was given a card with the outline of two ornamental designs from which he had to make a pencil copy, freehand, on a slightly larger scale. Tracing paper, a ruler or any measuring instruments were forbidden. He had a brief pang of conscience when he found that he had automatically checked the design’s width and height with his pencil. He was afraid it might disqualify him. Ought he to own up? He never did.

CHAPTER 2

National Art Training School

1893–1898

‘Crane’s appointment was like a sudden rush of fresh air.’

William found lodgings half a mile from the National Art Training School in a Dickensian bedsit in Merton Road, Kensington (now Kelso Place). Most of the original cottages and terrace had been demolished to make way for the Metropolitan and District line underground. Part derelict, part rebuilt with inferior buildings, Merton Road was no longer a true city street. To the east a filthy right of way forged a route to the Midland Railway coal yard. On the south corner, two builders, by chance named the Simmonds Brothers, owned premises. Facing Merton Road itself, blocking out the sun, stood a vast redbrick infirmary and workhouse, home to 400 mostly aged and infirm paupers, who looked out forlornly at William from the tree-covered courtyards and arcades in their ‘airing grounds’.

Towards Exhibition Road the area changed radically into prosperity. The late-Victorian London of 1893 that greeted the seventeen-year-old William Simmonds was one of the most exciting places on earth, the first modern metropolis, with its underground railway, its busy streets, its gas and electric street lighting, its thick grey fogs and its vivid glimpses into an elegant fashionable world. Great things were afoot in the outside world – the Boer War, the Irish Independence movement and the foundation of the Labour Party – but William, innocently apolitical, was cocooned in his own aspirations. As he wove his way between the Hansom cabs to cross the main road and passed the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) to the School courtyard, he felt exhilarated. Ahead of him lay entry to a new universe.

Amid the feverish change of the period, the School’s heavily bearded Principal, John Sparkes, seemed a timeless fixture. A student at the School forty years earlier, he had emerged as a qualified teacher and a budding scholar. He travelled in Europe to inspect German and Belgian art schools and had established himself as one of the most eminent educators in the land, with several scholarly books to his name. Back as the School’s Principal in 1875, he religiously kept to rules laid down by a previous headmaster, Richard Redgrave, a protégé of Prince Albert’s favourite benefactor, Henry Cole. He had recently lost his wife, his eyesight was deteriorating and he had become prone to bouts of irritability. But retirement was never spoken of. Two damaging reports, commissioned by the School’s board of trustees, had heavily criticised both him and the staff, but they gathered dust and no one pressed Sparkes to accept their conclusions.

William soon became familiar with the rigid teaching methods in the curriculum. The School’s stated aim was to train teachers and craftsmen rather than painters of ‘easel pictures’, through a course of twenty-three steps, learning the ‘grammar of design’. The deeper social purpose was to elevate the status of the designer-craftsman so as to engender respect from industrialists and manufacturers.

William’s introductory class was the elementary course on Geometric Principles, some of which he had already covered in the Royal Albert Institute. From there he progressed to line drawing from plaster casts of classical sculpture and antique ornaments, then to shading in chalk and charcoal. Each task, worked on for weeks, sometimes months, had to be completed to the instructor’s satisfaction before he could move on to the next. Typical was the teaching of Roman lettering. The class was given an alphabet of large Roman letters on separate cards. Each morning they had to do a letter, starting with ‘A’, by making a tracing of it. This they did every day until they knew by heart all the properties and proportions of the letter and could draw it freehand without tracing, at which point they moved on to the next letter. To the end of his life William considered these lettering classes to be an introduction to one of the high points of civilisation.

One teacher stood out from the mediocrity of the others. Edward Lanteri’s lucid sculpture demonstrations were always packed. With his beguiling French accent and charismatic energy, he awakened an astonishing enthusiasm among students who, under the rest of the staff, seemed dead to their studies. The warmth of his personality left his pupils with a lasting affection for him.1

Lanteri thought the copying of idealised Greek classical casts too testing for beginners and gave them instead more striking and distinctive pieces such as Donatello’s Lawyer and the head of the joint Roman Emperor Lucius Verus (AD 161–9). Like Sparkes, he believed that drawing practice was even more important for sculpture than for painting. ‘Only by understanding the body’s anatomical structure,’ he wrote, ‘will the sculptor avoid groping in the dark, gain confidence and find the necessary powers to express truthfully, in the simplest, fastest and surest means, his personal vision: and only then will he be ready to move to the living model.’

Lanteri never tried to restrict his pupils’ creativity. In fact he thought individuality the essence of art, a ‘supreme gift’ granted to few, distinguishing it sharply from eccentricity or artificial striving after originality, both of which usually led to ‘deplorable’ results. His scholarship encompassed an understanding of every type of animal, not least the horse – the placing of the bridle, the importance of the mouth, the paces, ease and uniformity of movement in trot, walk and gallop. Following his own observation of the cart horses and trap ponies of Eton Wick, William became fascinated with the much greater possibilities of wild animals, listening intently to Lanteri on the horse, lion and bull.

William soon discovered another way of satisfying his thirst for wider knowledge. Close to the School the enormous South Kensington Museum bewitched him with its hotchpotch of rooms. He discovered 5,000 years of art in virtually every medium: metalwork, furniture, textiles, paintings, drawings, prints and sculpture. And among these remarkable collections sat some contemporary work, illuminated by the historic forerunners that had helped to shape it.

He would spend hours drawing in different halls. Unable to afford a meal in the green dining room, with its lavish William Morris tiles and beautiful stained-glass windows by Edward Burne-Jones and Philip Webb, or even tea in any of the museum’s other refreshment rooms, he always ended up on the padded seats in the room with the Raphael Cartoons, the only place where he could sit and relax. Just once his savings allowed him a meal of buns and cheese in the grill room, where the cook varied the menu to suit the social standing of its customers.

Most important to William were the School’s visiting lecturers who came several times a term to the astoundingly grand lecture theatre on the first floor. They descended like demigods into an auditorium lit by an enormous gaslight with some 700 fishtail burners, there to be worshipped by inferior mortals. Their ‘performances’ often included slides from the museum’s collection, introducing students in this way to the vast range of its contents. A favourite, Professor Arthur Thomas, lectured on anatomy, which he expounded with magisterial brilliance, clarity and no little drama: he could draw parts of the body simultaneously with both hands on the blackboard. He would bring on to the stage a model to strike positions and demonstrate muscular attitudes; sometimes, with his long bamboo stick, he would point to the hanging bones on a gruesome skeleton that swung from a ring in its skull as if from the gallows.

But William found the permanent staff a disappointment. Their teaching practices worsened with each month. They would turn up intermittently and had little dedication, having received their Teacher’s Certificate many years ago and, as time went by, they relapsed into resentful indifference. The cause of their dissatisfaction was the drop in the number of fee-paying students, from whom they derived the bulk of their income. With their pockets affected, they took it out on the scholarship students, whose work they randomly savaged. William’s new grant increased his maintenance allowance but specified that he could only remain if he did well ‘term by term’. As a scholarship boy, he felt the strain more than most as he awaited the result of his end of term report. Nevertheless he stuck at it: he was determined to show he could survive independently of his father.

After a year of frequent exams and dauntingly hard work, William obtained his Art Master’s Certificate and entered the next four-year phase of the teachers’ course as ‘a student in training’. The same teachers were on hand.

He was now allowed into life drawing, where the standard was what was known as ‘Sight-Size’. An object was to be drawn exactly as it appeared to the artist on a one-to-one scale, so that when viewed from a set vantage point the drawing and the subject had the same proportions. Students measured the subject using a variety of measuring tools such as string, sticks and a straight arm. The aim was accuracy and realism. Rejecting the romantic idea that the academic discipline of art schools stifled the imagination, he knuckled down to learn all there was to know about the theory and practice of drawing.

With little daytime supervision, William found he could go into any classroom and set up his materials. The students gathered in knots, chatting idly and occasionally breaking out into rowdy horseplay. If a lesson was more than ordinarily boring, he and his friend Charlie Pibworth, the son of a Bristol cobbler, passed the time sketching each other or the lecturer, under the guise of taking notes. Discipline had collapsed in mutual disrespect between staff and students. A lecturer who paused for a drink of water would be greeted with ironic applause; but William kept his head down, intent on obtaining his qualification at all costs.

He could attend as many lectures he wanted. Not so the female students. Separation of the sexes was complete. They were taught in different buildings, although at one point the two staircases touched. With less instruction than the men, the women had a strong feeling of being disadvantaged. Most of all they resented not being allowed into the life classes. The evening lectures at the museum were another bone of contention: the women were not allowed out after dark unless chaperoned.

The one place that the two sexes could meet on the School premises was in the art clubs, of which there were many: including Design, Figure Design and the Black and White Club. A tense moment came once a month when the students’ work was placed on the walls for a master to criticise. The experience could be bruising. During one criticism-session, Sparkes himself was in charge and condemned the efforts of Janet Roberts, a rich student from a conventional Victorian family, as ‘shoddy, commercial and Christmas cardy’. She kept a stiff upper lip until the end of the seminar, then fled to the ladies’ room in the ABC tea shop beside South Kensington station. There William and Charlie Pibworth, who had witnessed her earlier humiliation, saw her in tears and invited her to the common area for a consoling cup of coffee. Pooling their sixpence daily food allowance (or ‘remission of feeds’ as it was called), they bought her an ABC special – a lunch cake. It was virtually unheard of in those days for the fee payers to mix with the poor scholars from working class backgrounds, but Sparkes’s outburst was the start of an improbable friendship between Janet and William – albeit one that progressed no further than short conversations.

Despite her sheltered life, William noticed that Janet Roberts, separated in the Design Department, was no shrinking violet when it came to her own education. When she became interested in embroidery and then the Arts and Crafts movement, she was determined to hear a lecture by William Morris’s daughter, May, the embroiderer. In the absence of a suitable maiden aunt, Janet persuaded her mother to send their cook as chaperone to escort her home after dark from the talk. To avoid confusion caused by the many entrances to the museum, Janet had arranged to meet her under a copy of Michelangelo’s David, recently made decent, in case of a surprise royal visit, by a stone fig leaf retrieved from the museum basement. Confused by the size of the statue, the cook mistook it for Goliath and wandered off in search of David, leaving Janet waiting on her own for half an hour beside the statue. The hitch was typical of the minor obstacles faced by the female students. William bumped into her there and chatted away about May Morris until the cook reappeared.

The School’s isolation from artistic currents outside its walls was total. Most students were largely unaware of the revolutionary movements turning Victorian preconceptions upside down. Not only was Impressionism never mentioned by the staff, but even the English Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts movement were studiously ignored. Thus Janet’s enthusiasm for William Morris’s designs and the new shop Liberty, which promoted Arts and Crafts furniture, was of no interest whatsoever to her teachers. This was the more surprising because Morris’s ideas and philosophy and his followers’ efforts to make art accessible to the general public and to resist industrialisation coincided with the School’s own aims.

It was not until the autumn of 1896, when the School suddenly found itself in the spotlight, that changes within the system began to take shape. Journalists had been shocked after an unexpected announcement that the Queen had given permission for the National Art Training School to change its name to the Royal College of Art. It would be granted the right to award diplomas. An article in The Studio magazine led the outcry: they queried the School’s right to a royal title when its methods and practices, so recently lacerated in reports, showed no improvement.

The following year, as the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebration in June drew near, crowds surged in from the provinces. Flagpoles swathed with garlands lined the streets, and drapes and more flags hung down from windows and balconies. A small town of canvas tents was pitched in the park to receive troops from all parts of the Empire. The Queen’s remoteness was felt and resented: her prolonged mourning of Prince Albert, dead now for over thirty years, had made the monarchy unpopular. But on this day, her sixty years on the throne revived the nation’s affection and respect, even awe.

At the end of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebration, William and friends mingled with dancing costa-girls outside the Pears store in Oxford Street

From an advertisement in a local paper, William had picked out a bakery south of the river as a vantage point from where to watch the procession. Detachments of soldiers lined the streets. Among the sandwich booths, picnic breakfasts and straw hats and boaters, the music of bands rose above the murmur of the crowd as it assembled in ever increasing numbers in the hot sun. It would be the hottest day of the year.

The Queen left Buckingham Palace at 11.15 am, followed by a glittering array of emperors, kings, princes and grand dukes and heads of state in uniforms of all colours, Indian princes in turbans displaying swords glittering with precious stones and, from Germany, in honour of Prince Albert, a magnificent old hussar and a grand cuirassier. Then came overseas troops: men in turbans, helmets and fezzes, all loudly cheering.

Slowly, majestically, the procession passed through Piccadilly Circus to St James’s Street, the Strand and Fleet Street to reach St Paul’s Cathedral. Here the Queen was greeted by the Archbishop of Canterbury. By now, because of her age and bulk, she had great difficulty moving, and she remained in her carriage for an open-air thanksgiving service and a Te Deum sung on the cathedral steps.

At last they crossed London Bridge and William’s long wait was over. Craning his head out of the top floor window of the bakery, he saw carriages and horses, with rosettes on their harnesses and ribbons on their tails, slowly approaching to ripples of applause that grew to roars of cheering as the cavalcade turned the corner. A strange hush descended on the crowd. You could hear the clip-clip of hooves in the silence. Slowly and steadily eight cream-coloured horses covered in purple trappings came into view, drawing an open carriage set on springs. In it, for all the world to see, sat the tiny round Queen, rocked gently from side to side: a stately old lady with a bonnet and a white osprey feather on her head, and in her hand a black, white-laced parasol to protect her from the heat of the sun. As she drove by she bowed constantly to left and right. She was pale and almost overcome by the warmth of her reception; tears were streaming down her face.

Then over Westminster Bridge and back to Buckingham Palace, where the Queen appeared on the balcony in her wheelchair, waved to the cheering crowd and disappeared into the shadows of the palace.

If for the Queen the business was finished, for the Londoners it was not. They streamed into overcrowded buses and shouted excitedly from the open top decks. In the early evening William and his friends joined the crowds in Green Park. In Oxford Street, they watched coster-girls dance outside the Pears store, its massive shop window twinkling with coloured lights as if freshened with the famous garden-scented Pears soap, before leading their men on to revel throughout the hot night in Piccadilly, dancing to the music of the concertina and dipping hankies into the drinking fountains. In King Street fairy lights and gas signs were turned on. By ten o’clock the whole of Mansion House, swathed in flowers, was lit up. For the first time a royal pageant was illuminated by electric light. William, however, had left long ago. He was exhausted.

In William’s last year (1898), just as the recommendations in the board of trustees’ reports were finally to be adopted, Sparkes suddenly announced his retirement. The government appointed the Board of Education to run the School, by now renamed the Royal College of Art, and, in an act of daring, brought in Walter Crane as Principal and teacher.

Crane’s appointment was like a sudden rush of fresh air. At the Manchester School of Art, he had established a reputation as an inspirational teacher. A brilliant illustrator of children’s books, published and exhibited throughout Europe, he had been converted by William Morris to Socialism. Crane was also a protagonist of the Arts and Crafts movement and involved in the Art Workers’ Guild, a union in which applied art, architecture and design were as highly valued as fine art and craftsmen of all sorts met as social equals. He also set up the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. If Morris was Socialism’s universal artistic genius, its most original writer, poet, lecturer and polemicist, Crane was the movement’s artist. His cartoons and drawings were blazoned on trades-union banners, published in Socialist newspapers accompanied by stirring poems, or sold separately to be pinned up in homes, factories and meeting places. The images he invented became the ultimate propaganda tool.

A shy man, short and fine-featured, he had immense drive and conviction as an artist, a craftsman and an adventurous – almost revolutionary – educator. He despaired at the way in which industrialisation had impoverished design; to him it was a terrible blight, an assault on the very soul of the nation. The highest standards of art must not only be saved from obliteration, they should, he insisted, be available to people of every walk of life.

Within a few days of his arrival Crane had planned a drastic reorganisation. He found the School ‘in a chaotic state … run as a sort of mill to prepare art teachers’. He would restructure the curriculum, expand the range of studies and rescue design from its role of decorative addition, irrelevant and unrelated to anything: he would return it to its proper status as the expression of an object’s essence.

Drawing, he thought, should not be mere skill in copying but a creative process based on a close study of nature. The School should have a conservatory and an aviary. In learning to draw, students should make rapid sketches from life and then elaborate them. They should develop their powers freely. The copying of casts and historical ornaments should not be their sole reference and guide. He would bring in memory drawing and the study of figures in action with the help of the photographs of men and animals in motion by the pioneering English photographer Eadweard Muybridge. It was the antithesis of the stultifying methods of the old school.

On the principle that the best teachers were generally those who kept in touch with commercial realities and could help the students when they left, he acted quickly to bring in a new wave of practising potters, printmakers and bookbinders as evening lecturers, including the illustrator Joseph Pennell from the Slade, and May Morris, a rare business woman who managed her father’s shop, Morris & Co.

All grades of student would be free to attend the life class, including women – to whose demands for equality he was sympathetic. He believed female students, just as much as the men, should gain technical knowledge of materials and the insight to adapt their designs to those materials for which they felt most sympathy.

William’s first encounter with the work and approach of this prominent figure in the Arts and Crafts movement was a formative experience. Perhaps because of the shyness he had in common with Crane, a strong rapport developed between them. In explaining to William the symbolism in ancient design, Crane would reach for sheets of drawing paper, seize a crayon, deftly sketch a four-footed cross and explain how this image of ‘the axial rotation of the heavens round the poles’ had evolved into decorative designs familiar in archaic pottery, Roman altars and Scandinavian, Celtic, Saxon and Asiatic ornament. He would demonstrate a stream of designs of Syrian and Greek ornament and the frequent appearance of the owl in hieroglyphics. Sometimes he would switch, mid stream, to a tirade denouncing the Empire, which had ‘crushed the arts in far away countries … the sole objective in our modern industrial system of society was to produce not “a thing of beauty and a joy for ever but something that would sell …”’. His advice to William personally was that ‘Our English designers should throw into their art all they knew of their English life and surroundings, instead of going on copying Roman and Greek ideas. Was there no beauty or suggestiveness in our English fields and gardens in the fresh glory of springtime?’

Private tutorials were one thing, but William was astonished by Crane’s inability to express himself coherently in public. He had to have a pencil in his hands or a blackboard in front of him to cope at all. At his first Club criticism in the Lecture Theatre in the spring of 1898, Crane stood with his back to the audience, gazing at the drawings around him. For what seemed an age, he fiddled with his hands and at last managed to get out: ‘This … this … this … composition – this design … this painting needs, needs, needs … some of the quality which it lacks.’ That was all. Nonetheless the students always asked for more.

But as Crane’s year progressed the old guard closed ranks, obstructing whenever they could. The ancient life class master, infuriated by the students Crane had let into his class, set them a difficult anatomy test and failed all but one; the Director of Art gave unexpected notice, forcing on Crane new responsibilities including the Summer Course for Teachers. To William’s pleasure, Crane awarded him first prize for a figure subject in the Summer Sketch Club. By the start of the autumn term Crane became ill. In October he wrote to William thanking him for his letter: ‘glad to say I am better and pleased to offer the Black and White Club a criticism of the drawings each month.’

After several bouts of illness, the truth became clear. Crane’s poor health and nervous stress were caused by the knowledge that he knew his reforms could never succeed: the old inflexible rules for obtaining the required Teachers’ Certificate would continue to hold sway, and the other teachers – with the exception of Edward Lanteri, for whose teaching methods he had the greatest respect – would support them. His vision and idealism were not enough. He could take the departmental infighting no more. After his brief tenure of a mere eight months, Crane resigned.

Among the students rumour was rife: the resignation of their charismatic principal was due to the jealousy of the teachers; others whispered that Crane had been hauled over the coals for paying too much attention to the female students – particularly after he bought one of the girls a beautiful flame-coloured azalea. He had given the students confidence to face up to the more troublesome teachers. One of the many victims of the life class master was Janet Roberts. With Crane gone there was no principal to appeal to when she was thrown out of the life class. She went into action and entered her work for the life exam. To her astonishment she was awarded a star above first class honours. On hearing the news she marched back in to the life class room with head held high, ignoring the master as completely as he continued to ignore her.

Before Crane left, William confided to him that he did not want to devote his life to either design or teaching (something he had never let on to Sparkes) and asked for his help in applying for admission to the Royal Academy School to train as a professional artist. To Crane the Royal Academy stood for much of what he most disagreed with, but ultimately it was one of the most prestigious institutions in Europe. Ironically, his ambitious wife had tried for years to get him elected as an Academician, without success. He immediately wrote the letter of recommendation.

Even though William’s four years at the National Art Training School had coincided with the School’s low point and period of self-doubt, its legacy to him was entirely positive, and one he would never regret. Like Edwin Lutyens before him and Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth after him, he always spoke with pride of what the National Art Training School and the South Kensington Museum had given him and of the freedom its students felt to follow whatever artistic path they might later choose. He left the school liberated, proud of his achievements. The grounding he had obtained was his for life.

CHAPTER 3

Royal Academy Schools

1899

‘Everything in nature is moving, nothing stands. Weather is a capricious master whose whims must be met … record nature’s moods and study the work of great men, Turner and Constable.’

William’s teacher George Clausen paraphrasing the words of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus

One morning in early January 1899, William walked east through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, passing his old school on the right, then on to Green Park. He had kept his dingy lodgings in Merton Road. The evening meal was monotonous and unappetising but the room was cheap and he could afford nothing more. Not that he was seriously worried about money. The Royal Academy offered free tuition and grants for maintenance and materials.

A few yards short of the heavy wrought-iron gates of Burlington House in Piccadilly, feeling as awestruck as he had been on his first introduction to Kensington, he turned off through an arched stone doorway into a narrow wooden passage and slithered along its icy surface towards the almost hidden entrance to the Royal Academy Schools. In the hall he was met by Laocoön, the mythical priest, wrestling in agony with his two diminutive sons against giant serpents sent by the gods. And, stretching ahead down the long corridor, an avenue of more classical casts copied from the British Museum or donated to the Schools by the Academy’s first royal patron George III, among them the famous statue of Hadrian’s lover Antinous.

The most important figure in the running of the Schools was the Keeper, whose august standing was indicated by his occupation of a residence attached to Burlington House (the main building of the Academy itself) with a private studio and enough room for his family, a cook and two maids. Traditionally a practising artist, the Keeper, with two curators under him, looked after the smooth running of the Schools, the library and the casts and was in charge of discipline, which included monitoring the attendance of the students. He now gestured peremptorily to William to turn left into the lecture room, an imposing wooden-floored studio with north-facing windows flanked by velvet curtains.

It was here that Visitors’ lectures and life classes were held. Sturdy anglepoise lamps jutted from the wall, their iron shades shaped like coned shells. On the shelves were more plaster casts and, near the stage, a large freestanding horse on a trolley, head down, neck arched and pawing the ground. Facing the entrance was a two-tiered semicircle of leather-padded benches with attached wooden pencil trays. Already seated in the front row were two National Art Training School alumni, William’s friend Charlie Pibworth and Walter Webster. Within minutes dozens more new students drifted in, half of them painters, the rest sculptors or architects.

The Academy was proudly independent of government control. Its members were all practising artists, elected by a self-perpetuating committee. Rather than employing permanent instructors, the committee selected from their membership nine ‘Visitors’ a year, to serve for a month each as teachers and mentors. Their duties were to examine and instruct the students and to set the live model’s weekly pose, for which they earned a salary of a guinea a night, forfeited on failure to turn up. The models – four per term – were chosen by the Keeper and booked for three days a week. A life class curator would sit in on every session to ensure discipline and propriety.

For the first year William was on probation and could not touch a paintbrush. It took resolve on his part to prolong his drawing. He had to attend more lectures on anatomy and perspective, and submit daily exercises in drawing from antique casts. Later, to prepare for being allowed to paint in oils, he had to learn once more the art of drawing with charcoal, but this time with white chalk on toned paper to develop his understanding of grades of light and shade.

His uncomplaining acceptance of this regime was not unusual: it reflected the conventions of the time. Two centuries before, the Academy’s first President, Joshua Reynolds, had modelled the Schools on the ateliers of Europe, in particular the French Academy of Louis XIV. In a series of discourses, celebrated for their philosophical depth and historical range, Reynolds had lectured on the importance of copying the Old Masters and drawing from life and classical casts. Art was to be learned by training not just the hand and the eye but also the mind. Such a regime would form artists capable of creating works of high moral worth. Reynolds was suspicious of ‘originality’: ‘Every opportunity should be taken to discountenance that false and vulgar opinion, that rules are the fetters of genius … rules are fetters only to men of no genius.’ There was a hint of Plato’s mistrust of undisciplined art in Reynolds’s lectures, and the ethos had survived to William’s day.

Over the decades artists and teachers had fought against the elite practices of the Academy and its Schools. Irritated by its monopoly of power, new generations had periodically set up breakaway movements, established less imposing galleries in which to display their work, or – particularly annoying for the Academy – departed for the continent to complete their education. But the committee was cunning. At crucial moments it had invited recalcitrant artists to ‘join the club’ and offered them the honour of membership: Edward Burne-Jones and John Singer Sargent were among its more recent successful seductions. At the turn of the century, the Academy’s standing as the most prestigious art school in Britain was still unquestioned. William had no social standing and no pretensions to genius of the kind that would attract the attention of the artistic community. Membership of the Academy was his only hope of achieving recognition; only through the Academy could he meet and come to know the artists and critics of the day.

That first week of January, the week of William’s arrival, four paintings by the brilliant neoclassical artist and founding member of the Royal Academy, Angelica Kauffman, had been discovered stacked away, deteriorating in the basement. These were being cleaned and relined to be inserted into circular mouldings in the entrance hall ceiling. William found the two imposing allegorical women depicting Colour and Design particularly beautiful. Kauffman’s neglect seemed shocking.