18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

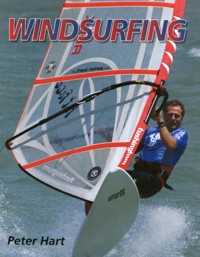

Combine the thrill, freedom and exhilaration of surfing, skiing and sailing, and you have an understanding of the attraction of windsurfing. This book is the ultimate guide to windsurfing; packed full of information and with photographs by John Carter, it offers a full explanation of equipment, a detailed description of the basic as well as intermediate and advanced techniques, and has specific chapters on planing, sailing smaller boards, gybing, wave sailing and much more. With over 200 great photographs, informative diagrams, a glossary and list of useful addresses, this is the complete guide to the sport.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

WINDSURFING

Peter Hart

The Crowood Press

First published in 2004 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Peter Hart 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 963 6

Disclaimer Windsurfing is a potentially hazardous sport. The author and publisher disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

Dedication To the memory of my father, a man of the sea, and to my mother, who bravely put up with the obsession.

Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Annette Hart for her skill on the water and her patience at home; David White and John Carter for their efforts in the searing heat; and Tushingham Sails and Starboard boards for their continuous support.

Principal photographers: John Carter and David White

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Equipment

3. Understanding the Wind

4. The Basics

5. The Harness and Footstraps

6. The Waterstart

7. Sailing a Smaller Board

8. Gybing

9. Manoeuvres

10. Sea Sailing

11. Wave Riding and Jumping

12. Freestyle

13. Windsurfing Competition

Glossary

Useful Addresses

Index

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT WINDSURFING

Windsurfing. The name sums it up so well. You may never have surfed a wave but you can surely imagine the exhilaration of skimming over the water on a tiny craft, driven along by a clean, noiseless energy. Just replace the wave with a sail and some wind and you will come close to understanding the thrill, freedom and accessibility of windsurfing.

This sport of ours has come a long way since its crude beginnings in California in the late sixties, when the pioneers played around with what was little more than a Malibu surfboard and a colourful bag. Since then it has become an Olympic sport. Windsurfers have crossed the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They have held the record for the fastest wind-powered craft, having clocked speeds of 80kph (50mph). Windsurfers jump, fly and ride 12m (40ft) waves. The top performers follow a professional world circuit where they compete over a variety of disciplines such as racing, freestyle and wave sailing. However, the windsurfer is also a very versatile craft, equally at home on the gentle waters of an inland lake and in the towering surf off Hawaii. And as a result, despite its ‘whizzy’ image, people of all ages and abilities enjoy windsurfing.

And is it difficult to learn? If, without any guidance, you take out an old board in a choppy sea on a windy day, it can be close to impossible. But, as the following pages will show, given some light, modern equipment, a gentle breeze, flat water and a game plan, almost anybody can learn to sail, turn round and come back within a few hours.

But to stop there would be like watching the adverts and then leaving as the credits roll for the main feature. It is the relentless mental and physical challenges of moving into stronger winds on higher performance gear and trying the endless moves, which leaves millions of people eternally gripped by windsurfing.

A PATH TO THE TOP

Here is your route to windsurfing mastery.

Step 1 – Up and Back

Your career starts in a light wind, on a large, stable board with a small and very light sail. In this first session you are bombarded with new sensations. You re figuring out how the wind works, how the sail drives the board at the same time trying to keep your footing on a sensitive platform AND control the pull in the sail. Yes at first there is a touch of slapping your head and rubbing your tummy with different hands syndrome but it all falls into place very quickly. The key aims are to learn how to raise the rig, turn the board round on the spot and take up a comfortable sailing position. To become the complete master of your destiny, you then learn how to steer and how to adjust body and rig for the various sailing courses.

The first session is about taking on the very basics of balance and board control. (John Carter)

A larger sail forces you to lean out against the rig. (John Carter)

You can experience the joys of planing within weeks of learning. (John Carter)

Step 2 – More Power, More Speed

Soon you realise that this is a Formula 1 car and you re using it do the shopping. The next step is to tap into more power either by using a bigger sail or waiting for more wind.

Suddenly the stakes are raised. You have to hang right away from the boom and use your body as a counter-weight. More power in the sail translates immediately into more speed, faster manoeuvring and the need for more precise technique.

Step 3 – The Harness, Footstraps and Planing

This is no longer a gentle mode of transport, it’s a sport and your already overworked arms are the first to feel it. Now is the time to attach the harness. The harness is a light, padded belt with a hook on the front, which fastens around your waist. Two lines form a loop on either side of the boom. When you drop the hook onto the line, you can then use your body-weight to take the lion s share of the force, leaving the arms free to make the minor adjustments.

The premier goal is to learn to handle enough power to make the board plane. Planing – it s what ALL windsurfers are fundamentally designed to do. Like a speed boat, when they reach a certain speed, they rise out of the water and skim along the surface. Your speed immediately doubles as does the thrill. The larger modern boards plane in relatively little wind so you can attain this Holy Grail of planing within a few weeks of learning.

With planing speed, you need an extra degree of control. Footstraps – loops on the deck that you slide you feet under – give you that control.

With your feet in the straps, you can hold a secure stance in the rough, keep your footing as water sweeps across the board and, ultimately, control the board in the air. You can fit and practise with the footstraps in light winds and at slow speeds. The idea is to get used to sailing and balancing with the feet locked in one position before doing the same in planing conditions.

Step 4 – Waterstarts, Smaller Boards, Carving Turns

As soon as your sail control in stronger winds is more or less instinctive, you learn the waterstart, a technique where you allow the rig to pull you out of the water and onto the board. It s a life changing skill which not only allows you to start off effortlessly in strong winds but which also allows you to experiment on smaller boards.

Able to waterstart and plane hooked in the harness and with the feet in the straps, your board is no longer a dinghy without a seat, it s a surfboard and needs to be handled as such. Steering from now on comes less from moving the rig and more from simple foot pressure. You want to turn left? Then pressure the left hand edge, bank the board over and feel it carve around like a surfboard or a waterski.

The carve gybe, an 180 degree downwind turn, is windsurfing’s blue riband move. Considerable forces build up if you throw any vehicle into a turn at 20 mph plus and you have to take up some dynamic postures to withstand those forces.

A small board carves through the turns like a water-ski. (Dave White)

Step 5 – Endless Avenues

Where you go from here depends on the level of your ambition and the conditions available to you. Waves, flat water, racing, trick sailing and gentle cruising all beckon if you have the time to practise and the right equipment.

HOW TO START

The easiest, safest and most effective road into the sport is through an official RYA (Royal Yachting Association) course. At centres that carry the flag, you can be confident that the equipment, instructors, sailing area, general facilities and rescue craft are all in place and up to scratch. The scheme itself is clear and logical – but that is the sort of appraisal you’re bound to hear from someone who has had a hand in developing it!

But it is certainly not the only way. Many people get into the sport through people they know, and friends often make good teachers because they are bursting with enthusiasm. You just need to be positive that your chosen friend is of sound mind and body and not the type who would send a non-swimmer out on to a churning ocean in an offshore wind.

The good thing about the RYA scheme is that there are specialist courses or ‘clinics’ for every level on every aspect of the sport. You can, therefore, dip in and out at any time to have either a technical makeover or to learn a completely new set of skills and manoeuvres.

There are recognized centres all over the world. Contact the RYA (seepage 174) to find the one nearest to you.

With the basic skills under your belt, the sky is literally the limit. (John Carter)

CHAPTER 2

EQUIPMENT

Close your ears, at all costs, to the following advice: ‘it doesn’t matter what equipment you choose because, as a beginner, you won’t be good enough to tell the difference’. Having the right gear is as important for the beginner as it is for the seasoned pro. If windsurfing has a reputation for being difficult to learn, this is entirely down to people being put on heavy old equipment of the wrong size and wrong design – sometimes by well-meaning friends, sometimes by less than reputable hire centres.

GETTING STARTED

At first, all you need is to be handed the right equipment and be allowed to get on with it. An advantage of learning at a recognized school is that you will be provided with a suitable board and rig that is set up for your height and weight, leaving you free to concentrate on balance and reacting to the force in the sail. If a friend is teaching you, be sure that the sail is no bigger than 5sq m.

Equipment makes more sense and becomes much more interesting once you’ve had a go. Find out how it all fits together, both to give you a degree of independence from the outset and so you can de-rig the sail on the water, stow it away and paddle home if the wind drops or you have some kind of problem.

Very soon after these first steps you will need to develop a deeper understanding of the equipment if you wish to continue to improve. Although boards and rigs are incredibly versatile and capable of operating in a variety of wind and sea conditions, they do have their limitations and the more exciting aspects of the sport are only open to you if you have the right equipment. You must be able to recognize when your current combination is holding you back and the time has come to trade up. However, more important than gathering a quiver of different boards and sails for every conceivable eventuality, is an understanding of how to customize and tune the equipment for your specific needs. Footstrap placement, rig tension, harness line position, boom height, choice of fin and sail size all exert a huge influence on your comfort and how well the board performs in different situations.

This photo of an entry-level model shows the footstraps, the mast-track, the slot for the daggerboard and the mast base. The board has a shock absorbing, soft rubber deck. Most boards, however, are simply covered in textured, non-slip paint. (John Carter)

The two light wind options: (above) a retracting daggerboard;(below) a removable central fin. (John Carter)

The Board and Rig(John Carter)

Boards for all seasons. From left to right: a Formula racing board; a de-tuned version for learning and improving in light to moderate winds; a 130ltr free-ride board for planing winds; a specialized freestyle model; and, on the far right, an 83ltr wave board. (John Carter)

The wider the board and the bigger the sail, the more fin area you need to resist it. The three more upright shapes on the left offer a good compromise between power and easy turning. The two short, wide, swept-back designs on the right offer extreme manoeuvrability for freestyle and wave sailing.

Volume in action – 200 versus 100ltr. No prizes for guessing which is better for light winds! (John Carter)

BOARDS – SIZES AND DESIGNS

Boards come in a bewildering variety of shapes, so volume, measured in litres, is the easiest dimension to relate to early on. The bigger the board, the bigger the sail it is designed to carry and the lighter the wind it is designed to be used in. Under the feet of an average adult weighing 75kg (165lb), any board with 170ltr of volume or more provides a stable platform for sailing in light wind. It is easy to sail and manoeuvre off the plane and therefore good for learning.

However, it is not a case of big boards being good for beginners and little boards being suitable for experts. The highest specification racing boards have upwards of 200ltr of volume. They need the buoyancy primarily to support the weight of a huge sail, which produces the power to get them scorching along in relatively light winds.

As you move down towards the 130ltr mark, the board will still support the weight of the sailor and rig when stationary but it is fundamentally designed for stronger winds and planing and therefore a higher skill level is required. In most instances it is too unstable for learning in light winds.

Boards below about 100ltr need to be moving before they will fully support the weight of the sailor (again, assuming a weight of around 75kg/165lb) and rig. An experienced windsurfer may have the skill and balance to climb on and pull the rig up in the conventional fashion, but he will be partially under water. From this stage on, the waterstart is the essential starting method.

As to which size of board is easiest to sail, it depends on the strength of the wind and the standard of the sailor. In light to moderate winds, beginners and intermediates will favour bigger boards due to their inherent stability. As the wind gets up, however, big boards become increasingly difficult to control. They bounce along the surface, the waves knock them off course and they present too much area to the wind, which can get under the hull and literally blow them out of the water. A smaller board, in the same conditions, stays in contact with the water and can be kept on course with the slightest heel or toe pressure, so long as it is under the control of a skilled pilot.

Volume only determines the wind range the board is to be used in and the weight and standard of the sailor it is designed for. The other design elements such as length, width and curve decide where its performance strengths lie.

Width and Length

Boards vary relatively little in length these days. With only a few exceptions, they are no longer than 2.8m with the shortest being around 2.2m. It is in the width of the board that the major differences lie. The big light-wind boards measure up to a metre at their widest point. The smallest high-wind board will be less than half that.

Building the extra volume into the width has been found to be far more effective than extending the length. A shorter, wider board is easier to control, more manoeuvrable both in rough seas and on flat water, and earlier to plane than a long thin board of the same volume.

Width in different sections of the board also makes a big difference to performance. A wide tail, for example, is good for early planing and tight radius turns but will make the board less controllable at high speeds. A narrow tail increases your control at high speeds and through long fast turns but is not so good for acceleration.

Other Features

Some more board design features you should become familiar with include:

•

The rocker line. This describes the curve of the board as viewed from the side.

•

The plan shape. The outline of the board as viewed from above.

•

The rails. The edges of the board.

It is difficult to consider these features in isolation, as it is how they all combine that determines the board’s performance and suitability for different conditions and sailing styles.

In general, straight lines and sharp edges translate into speed. Curves translate into manoeuvrability. So it is that both light and strong wind racing boards, whose chief weapon is speed, have parallel sides, a straight, flat underneath shape and sharp edges. All of these design features ensure that they skim smoothly over the water and meet with minimum resistance. To a certain degree, however, those same features hinder manoeuvrability and force the sailor into making long, safe turns.

At the other end of the scale, the wave board is curved in every dimension. The water sucks in around those curves creating more drag (less speed) but it also means you can bank the board over like a surfboard and it will follow the contour of those curves to make super-tight carving turns.

BOARDS – CATEGORIES

It is useful to understand the various board categories just to help you grasp what is being talked about in brochures, magazines and test reports.

There are two major categories: specialist boards, designed to excel in the competitive disciplines of racing, wave sailing, freestyle and speed sailing; and ‘allround’ recreational boards, designed to do a bit of everything.

The straight lines of the racing board and the curves and rounded rails of the wave board represent the two extremes of the design spectrum. (John Carter)

The UK’s Dom Tidy powering upwind on the traditionally shaped Olympic board. He is standing right out on the rail to balance the lift from the daggerboard. (Barrie Edgington)

Racing Boards

Windsurfing has a variety of racing disciplines with models for each.

The Olympic Board

In the Olympics, competitors all use the same model, which is selected some years before the games. Since the Barcelona games in 1992, the chosen board has been the Mistral One design. This traditional board is 3.8m long with a central daggerboard. Although wildly out of date as a design, it is still favoured by the authorities as it can be raced in the very light winds that often prevail at the Olympic venues.

Formula Boards

Almost as wide as they are long, Formula boards have taken competitive windsurfing into new areas both in terms of looks and performance. The revolutionary design includes a massive fin and sail, enabling the board to plane in winds of just 7–10kt (force 3). The racers compete around a long, square course so the board has to perform on all points of sailing – ‘upwind’ (towards), ‘downwind’ (away from) and across the wind – and it does so incredibly efficiently, often travelling at twice the speed of the wind.

On the downside, they are very expensive and, being a development class, they are soon superseded by something just a little bit better and so have little residual value. Despite being designed for winds under 20kn, the extreme positioning of the footstraps combined with the fearsome power of the sail and fin, make them a real challenge to sail.

Formula boards range in size from about 180–200ltr.

Slalom Boards

These are basically speed machines. Slalom, windsurfing’s re-emerging discipline, involves shorter races, mostly across the wind, with a number of gybe buoys (marks where you have to turn). The boards not only have to be fast but also manoeuvrable. The moderate wind models look like mini-Formula boards. On or off the racetrack, they are a lot of fun.

Slalom boards range in size from about 75–130ltr.

Wave Boards

Wave boards are fundamentally surfboards with a sail. The accent is heavily on manoeuvrability in the most extreme situations, like in the air and on the face of a wave. However, they are slower in a straight line and slower to accelerate and to plane than a more all-round design. The smaller wave boards offer the best control in high winds in or out of the waves.

Wave boards range in size from about 60–100ltr.

Freestyle Boards

The wave of weird and wonderful ‘new-school’, skateboard-style tricks has spawned a breed of board that is very quick to plane, turns on a sixpence, jumps with the slightest encouragement and has channels in the nose and tail to allow it to slide forwards, backwards and every which way. They are also relatively wide and stable enough to allow the trickster to recover from extreme angles. They sound like the ideal machine for improver and expert alike. But the one thing they are not so good at is blasting along in a straight line at speed in choppy water, and that is what the majority of people want to do.

Freestyle boards range in size from about 90–120ltr.

Free-Wave or Free-Move Boards

Part freestyle, part wave board, this hybrid is aimed at those who want to take their freestyle routines into small waves. They have the basic outline and nose ‘kick’ of a wave board to allow them to manoeuvre on waves and handle steep landings, but a straighter rocker line to give them more speed and acceleration.

Free-wave boards range in size from about 75–90ltr.

Free-Ride Boards

The ‘free-ride’ label was borrowed from snowboarding in the early nineties. Basically, it described the act of sliding around the mountain and then dealing with whatever you came across, be it groomed piste, powder snow, slush, bumps, drop-offs or natural jumps. Consequently, a very versatile snowboard was needed.

This is equally true in windsurfing – the free-ride board is designed to do a bit of everything in a wide range of conditions. The recreational windsurfer wants to go fast but also wants to enjoy the turns. One day he may be going for top speed on flat water; the next, the wind may have changed strength and direction and he finds himself in breaking surf trying to ride and jump small waves.

Free-ride is actually a pretty nebulous category encompassing all manner of boards. The biggest are de-tuned Formula boards. Although easier to sail, they are still designed to support a huge rig and get going in very light winds. Below that, the size indicates the intended use – the smaller the board, the higher the wind strength it is designed to perform in and the smaller the ideal sail size.

Free-ride boards range in size from about 80–200ltr.

Long and thin became short and fat and the process of balancing and learning became infinitely easier. The traditional shape on the right is actually quite wide compared to the original windsurfer. (John Carter)

Entry-Level Boards

People entering or returning to the sport are often surprised by the sight of the entry-level windsurfer. Most people expect a long and thin replica of the original Malibu surfboard but what stands in front of them is more like a door. What was once long and thin is now short and wide.

Although the traditional shapes still exist, the schools that continue to teach on them are few and far between. There are many advantages to the new shape but the main one is stability, the beginner’s ultimate companion. Stability at slow speeds comes from width not length, so it is that the wide boards are very hard to fall off. There is really no such thing as a dedicated beginner’s board on the market these days. The short, wide design favoured by many beginners is virtually identical to the highest performance racing boards. The only differences are:

•

The entry-level version will be of heavier but more durable and of impact-resistant construction.

•

It may have a soft rubber deck – a generally more friendly surface that absorbs the unsubtle scramblings of the beginner. It also offers a good grip – a slippery surface underfoot makes it impossible for you to relax and balance. It will have either a removable central fin or a daggerboard for stability in light winds.

•

It will have a vast choice of potential footstrap positions. Some are located far forward, just behind the mast base, so you can get used to using the foot-straps off the plane in light winds.

The huge advantage of learning on such a board is that it is wide enough to support a novice sailing in light winds, but it also has the design pedigree to accelerate smoothly on to the plane as the power increases, providing an easy and gradual introduction to higher performance windsurfing.

THE RIG

The rig, which comprises the mast, sail boom and mastfoot is effectively your motor. The amount of power produced is proportional to the strength of the wind and the size of the sail.

Little more than a colourful bag twenty years ago, the rig is now a highly precise aerofoil, constructed out of a mixture of sailcloth and exotic, non-stretch, see-through film. It is an extraordinary bit of kit. The fact that in breaking surf, it can be pummelled by literally hundreds of tons of foaming water and surface without a scratch, says enough.

It acts much like a wing, in that wind accelerates faster over one side to create a pressure differential, which in turn generates the lift to drive the board along. (Actually the board is sucked along but let us not disappear into the jungle of aerodynamics.)

Equally beneficial to the sailor is the rig’s ability to twist, flex and literally shape itself to the wind, and deal with the small changes in strength and direction – so long as it is properly tensioned.

Sails – Sizes, Designs and Categories

The most influential factors in sail design are the size of the sail and the wind strength it needs to be able to withstand.

For adults, sails range in size from about 3–12sq m. The largest are hugely powerful racing sails. The smallest are either for use in very high winds or for beginners looking for an easy time. The commonest sail sizes used by proficient adult recreational sailors who want enough power to plane in moderate to fresh winds are about 4–8.5sq m.

Just as with boards, there is a range of designs to suit the various sailing disciplines. And also like boards, it is important to strike the right balance between the mutually exclusive qualities of speed/ power and manoeuvrability. For example, a sail with a full shape will have a lot of pull and drive but will be heavy to throw around. A sail with a flatter profile will generally be lighter and easier to handle during manoeuvres but will be short on raw power.

Race Sails

These are hugely powerful, designed to handle a lot of wind and place the racer right on the edge of control. The wider luff tube accommodates ‘camber inducers’, tuning fork-shaped widgets that connect the batten to the mast and stabilize the front of the sail.

Wave Sails

Built to withstand the unholy forces exerted by breaking surf, wave sails have a flatter profile and so sacrifice some raw power in favour of manoeuvrability.

Freestyle Sails

Essentially very light in the hands and easy to throw around, freestyle sails provide good acceleration but often not the best top speed.

Free-Ride Sails

Free-ride sails make up about 90 per cent of all sails sold. Designed to work in a wide range of conditions, they are easy to rig and probably offer the best compromise between speed and ease of handling.

Masts

The mast is crucial to how the sail sets. Each sail is designed to take a mast of a certain length and stiffness. The stiffness is measured on the IMCS (International Mast Check System) scale, which measures how much the mast flexes under load. The scale ranges from 19 (soft) to 30 (stiff). Details of the appropriate mast are actually printed on most sails.

Carbon masts make the rig lighter and more responsive. Some wave sailors favour the thinner diameter ‘skinny’ on the left because of its extra strength. (Dave White)

Masts are usually made from a mixture of carbon and fibreglass. The higher the carbon content, the lighter and more responsive the sail feels. However, carbon is more fragile and more expensive.

Ever more popular are the narrower RDM (reduced diameter masts) or ‘skinnies’ as they are more popularly known. There is a continuing debate as to whether they improve the sail’s performance but it is indisputable that, due to the extra thickness of the walls, they are appreciably stronger and so a natural choice for many wave sailors. Smaller people, or least those with small hands, find them easier to grab and hang on to in mid-manoeuvre.

For ease of travel and storage, most masts break down into two pieces – and sometimes more if you abandon them in the waves! (Dave White)

Booms

Booms are made from high-grade aluminium or carbon. The latter is lighter and stiffer but more expensive. Unless it is to be used with a very big sail (7sq m plus), the benefits of a carbon boom are less marked as those of a carbon mast.

Booms have a telescopic back end, which usually extends about 40cm (16in) to fit a variety of sail sizes. To cover a reasonable sail range of about 4–7.5sq m, you can get away with just two booms.

Boom arms come in different diameters and the one you find the most comfortable will depend on the size of your hands, but many prefer the narrower gauge.

Starting Out

Nothing is guaranteed to sap both your energy and enthusiasm more quickly than repeatedly trying to heave up a heavy rig. This may be because the rig is too big but often it is down to certain schools using baggy, low-tec heaps of ancient junk. These days, a good school will use light monofilm sails and carbon masts – the difference is incomparable.

The instructor should assess your weight and the wind strength and relieve you of the burden of choosing a sail size. In the ideal learning conditions of a 3–6kt (force 2) wind (seepage 26) an adult weighing 70kg (155lb) would be using a sail of about 4sq m. It is important that the sail generates a reasonable amount of power so you are forced to counterbalance that pull with your body weight and develop an effective posture…and get a damp rap on the knuckles if you don’t. If the sail is too small or the wind too light, it’s like holding a damp lettuce leaf. You get no feeling for the trim and balance and so quickly develop a multitude of bad habits.

For your safety and pleasure, you have to get the right size rig for your standard, the wind strength and what you want to do. A giant 12sq m sail is perfect for racing champion Ross Williams but a 2sq m sail is better for his six-year-old apprentice. (John Carter)

OTHER GEAR

Windsurfing is a total immersion sport. Falling in is not a surprise or a shock; just part of the game, often the hilarious result of trying something new. Windsurfing has such an amazing safety record because we recognize that fact and dress for the water.

And please forget about the supposed cold. At most times of year, even in the UK, you will return from a session literally steaming thanks to the wonders of the modern wetsuit.

Wetsuits

First and foremost, a wetsuit has to keep you warm but it must also allow you to move with feline stealth and freedom. So it is that the modern wetsuit is basically an insulated, waterproof leotard.

A windsurfing wetsuit is made from either single- or double-lined neoprene rubber. Double-lined neoprene has a nylon layer bonded to both sides of the rubber. The nylon limits the rubber’s natural stretch but because it absorbs a little water it can lead to some wind chill – however, it is very durable and consequently the choice of most schools.

Single-lined neoprene, also known as ‘smooth skin’, has a shiny rubber finish like that of a seal. It is more flexible than double-lined neoprene and since the water runs straight off it, there is little or no wind chill. On the downside, it is more easily snagged and torn.

The thickness of the neoprene varies depending on the season it has been designed for. Winter suits are usually 4–5mm thick over the main part of the body. Suits for the summer and spring are typically 3mm thick and may also have short arms.

A snug-fitting, flexible, one-piece wetsuit with a little room around the forearms and shoulders is best for windsurfing. Despite the name, it should keep you as dry as possible. (John Carter)

The wetsuit works by keeping the body dry and insulated. If water does penetrate, it is trapped and forms a thin layer between body and suit. It is then warmed by the body and provides extra insulation. For this to work, the suit must be tight fitting over the legs and main part of the body.

The fit is as important as thickness to the warmth of a wetsuit. If it is baggy or, worst of all, loose at the neck, cold water flushes through the suit every time you fall in. If it is too tight, it takes a concerted effort just to move and breathe.

A well-stocked shop may carry suits for many different water sports so make sure you are in the windsurfing section. A suit designed for windsurfing has a more generous cut around the upper back so that it is comfortable when your arms are up and stretched out forwards. The forearms will also be looser to give those hard-working muscles room to expand and prevent cramp.

Windsurfers at all levels of proficiency will sometimes end up fully immersed. A wetsuit not only has to keep you warm but must also allow you to move freely and swim. (John Carter)

Footwear

As well as providing warmth and grip, shoes or boots protect the sole against sharp objects on the seabed and the whole foot should it slip and cannon into the mast base.

Specialist shoes and boots have a neoprene upper that is stitched and glued to a soft rubber sole. Shoes must be tight fitting or they rip off when you fall in.

You can use an old pair of trainers for learning but the thicker, heavier and stiffer the sole, the less sensitive you are to what’s going on, which is why a large proportion of experts elect to go barefoot.

Neoprene shoes for summer and boots for winter. (GUL International)

Gloves of any kind restrict your grip but this curved finger model helps you hang on to the boom. (GUL International)

Gloves

The modern boom has a soft, textured grip so gloves are not really necessary for your first sessions.

However, if you are susceptible to blistering or foresee a series of lengthy sailing periods – on holiday, for example – a pair of fingerless sailing gloves will go some way to prevent blistering. The problem is worse in hot climates where the warm water softens the hands.

Ultimately, the best protection against blistering is to windsurf as much as you can and develop horny calluses all over your palms.

Gloves of any kind are not popular as they restrict your grip on the boom, force you to hold on tighter and make the forearms give out prematurely. Even in the depths of winter, many prefer to go without. However, those who do wear gloves tend to favour one of the following:

•

Gloves with pre-shaped, curved fingers that help you grip the boom.

•

Palmless gloves or mitts. This open style of glove where just the top is insulated offers the best grip although the skin is open to the elements.

•

Washing-up gloves. Thin, cheap and useful for keeping the wind off.

Neoprene hats – very efficient without winning any fashion awards. (GUL International)

Hats

A huge percentage of body heat escapes through the head so a neoprene hat can prolong your sailing time by hours as winter closes in. However, as hearing has an extraordinary effect on balance, make sure the ears remain open to the wind.

Helmets

The latest water sports hard hat is light, comfortable and looks business-like. However, whilst some elect to wear one, the majority do not. I can offer no logical explanation apart from the fact that head injuries are rare and that helmets have yet to be fully absorbed into windsurfing culture.

There is anecdotal evidence that helmets can give you an unreal sense of your own safety and make you take unwise risks. I wear one when going for a new move, where I am not sure of the outcome. Some aerial moves, notably loops, which fail to go according to plan, can end up with you being slammed to the water on the side of your face. A helmet goes a long way to protecting you from a burst eardrum.

Windsurfing helmets are light and stylish these days. ‘Head injuries may be rare but you never know…’ is the philosophy of wave sailor Corky Kirkham. (John Carter)

A helmet will also protect you when windsurfing on crowded waters where there is a real risk of being hit by someone else’s falling rig. But enough of such horror stories – as a first timer, the school may offer you a helmet but you will not be made to wear it.

Buoyancy Aids

The message on buoyancy aids is straightforward – if it makes you feel happier and more confident in the water, then wear it. There is no stigma attached.

On a beginner’s course you will be asked to wear a buoyancy aid and they are also compulsory on certain inland waters that come under the jurisdiction of a local water authority. Otherwise, it is a matter of personal choice. The majority choose to go without.

In most situations, when you fall off, you surface right by your board, a huge buoyancy aid in itself. The wetsuit also has a certain amount of buoyancy. So you do not have to be a strong swimmer to enjoy windsurfing. In situations where you might lose the board – namely in breaking surf – a buoyancy aid can actually hinder you because it restricts your swimming action and prevents you ducking under the bigger waves.

However, a buoyancy aid can be useful for the more experienced windsurfer. In the waterstart, for example, it helps to float you in the start position and saves a huge amount of energy.

DRESS FOR THE OCCASION

I’m not afraid to admit this – I once entered the first stages of hypothermia whilst windsurfing in Barbados. I have also suffered from severe heat exhaustion and dehydration to the point where I could barely function whilst windsurfing in England.

In Barbados, I was enjoying a fantastic day in the waves, sailing just in a pair of shorts. After three hours, a rainsquall came through. The wind increased and the temperature dropped a little (by normal standards it was still baking). However, that combination of extreme physical effort, wind chill (the act of the wind literally whipping heat away from the skin) and a drop in temperature, was enough to make my body core temperature drop and for me to suddenly become disorientated and uncoordinated. Luckily I was close to shore.

Windsurfing clad only in a kilt, in the North Atlantic in October, is not to be generally recommended, but this is what you expect from eccentric Irishman Timo Mullen. (John Carter)

In England, I had simply put the wrong wetsuit in the car. It was a summer’s day and I was forced to wear a winter suit. Within half an hour I was teetering on the verge of collapse and barely had the energy to crawl back up the beach. The wetsuit was so efficient that the body had no way of cooling itself.

Dressing for windsurfing is about protecting yourself from the prevailing conditions. This may mean wearing a hat, a T-shirt and smearing yourself with factor 40 sun cream or wrapping every exposed square millimetre of skin in neoprene.

How you dress also depends on the sort of session you have in mind. For example, if you are planning an hour of general freestyle or intense manoeuvre practice in benign conditions on enclosed waters, you can dress fairly scantily. However, more clothing should be worn if you are off on a long coastal cruise where, in the event of a problem, you may have to spend a long time in the water.

As a general observation, I think that many people wear too much. I’m not suggesting doing anything that might lessen your general water confidence and safety but there are those who load themselves up with so many accessories that they lumber around like the first moonwalker. Freedom of movement is a safety aid in itself.

RIGGING

The act of assembling the rig is childishly simple. Every modern rig package comes with a detailed set of instructions specific to that brand so there is no real excuse for getting it wrong. Problems come from a failure to grasp what a colossal influence rigging has on performance, especially in stronger winds; hence in their haste to get out there, people hurl it together believing that it doesn’t really matter.

Slide the mast up the sleeve, pointed end first.

The mastfoot/extension fits into the base of the mast. The downhaul is then attached to the foot of the sail, in this case via a hook and pulley block. When it is tensioned, the hook will come down right to the base of the mast. The extension allows you to adjust the length of the mast to fit the sail exactly.

The jaws clamp around the boom and are locked in place by a lever.

The outhaul rope controls the fullness and power in the bottom of the sail. It threads through the eyelet in the clew and back into a cleat on the back of the boom. Tension it so the sail forms a smooth curve and the belly of the sail is not touching the boom. Adjust the length of the boom so that the clew pulls right to the end.

Rigging Sequence(John Carter)

To pull on the downhaul tension, put one foot on the mastfoot and then straighten the leg rather than trying to pull with the arms. Tension it so the front of the sail is taught and solid, the head of the sail is flat and the leech a little loose.

Tuning

Having a basic knowledge of how a sail works helps you understand how altering its tensions and shape will affect its handling.

You can roughly divide the sail into two halves. The bottom half is the engine and the top half is the exhaust pipe. From the batten above the boom downward, the sail is designed to produce the power. Its shape, foiled like a wing, shouldn’t change under load.

The top half of the sail is designed to change shape. Under load, the mast bends, the ‘leech’ (the sail’s trailing edge) twists open and allows the air to escape. To a certain extent the modern sail is self-trimming. Because the top half can flex, it is able to soften the effects of gusts and lulls. Without that flexibility, you would feel every pressure change and would constantly have to adjust the sail angle to avoid being pulled off balance.

The amount of power the sail produces and the degree of twist and flexibility is controlled via the downhaul and out-haul ropes.

The Downhaul

By downhauling you put tension into the front of the sail, which is essential to its stability. It also compresses the mast and makes it bend. Being thinner, the top bends more and, as it does so, the head of the sail flattens off. Downhauling also makes the leech go loose, which allows the sail to flex and twist.