10,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

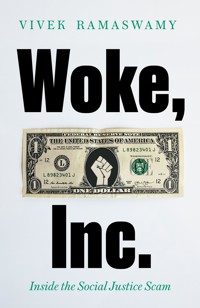

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A young entrepreneur makes the case that politics has no place in business, and sets out a new vision for the future of capitalism. The modern woke-industrial complex divides us as a people. By mixing morality with consumerism, corporate elites prey on our innermost insecurities about who we really are. They sell us cheap social causes and skin-deep identities to satisfy our hunger for a cause and our search for meaning, at a moment when we lack both. Vivek Ramaswamy is a traitor to his class. He's founded multibillion-dollar enterprises, led a biotech company as CEO, trained as a scientist at Harvard and a lawyer at Yale, and grew up the child of immigrants in a small town in Ohio. Now he takes us behind the scenes into corporate boardrooms and five-star conferences, into Ivy League classrooms and secretive nonprofits, to reveal the defining scam of our century. But this book not only rips back the curtain on the new corporatist agenda, it offers a better way forward. Corporate elites may want to sort us into demographic boxes, but we don't have to stay there. Woke, Inc. begins as a critique of stakeholder capitalism and ends with an exploration of what it means to be a member of society in 2021 – a journey that begins with cynicism and ends with hope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 514

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

SWIFT PRESS

First published in the United States of America by Hachette Book Group, Inc. 2021

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2021

Copyright © Vivek Ramaswamy 2021

The right of Vivek Ramaswamy to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-800-75067-8

eISBN: 978-1-800-75068-5

TO MY SON KARTHIK, AND TO HIS GENERATION.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION The Woke-Industrial Complex

CHAPTER 1 The Goldman Rule

CHAPTER 2 How I Became a Capitalist

CHAPTER 3 What’s the Purpose of a Corporation?

CHAPTER 4 The Rise of the Managerial Class

CHAPTER 5 The ESG Bubble

CHAPTER 6 An Arranged Marriage

CHAPTER 7 Henchmen of the Woke-Industrial Complex

CHAPTER 8 When Dictators Become Stakeholders

CHAPTER 9 The Silicon Leviathan

CHAPTER 10 Wokeness Is Like a Religion

CHAPTER 11 Actually, Wokeness Is Literally a Religion

CHAPTER 12 Critical Diversity Theory

CHAPTER 13 Woke Consumerism and the Big Sort

CHAPTER 14 The Bastardization of Service

CHAPTER 15 Who Are We?

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

INTRODUCTION

The Woke-Industrial Complex

MY NAME IS VIVEK RAMASWAMY, and I am a traitor to my class.

I’m going to make some controversial claims in this book, so it’s important you know a bit about me first. My parents immigrated from India forty years ago to southwest Ohio where I was born. They weren’t rich. I went to a racially diverse public school with kids who came from difficult backgrounds. After I got roughed up in eighth grade by another kid, my parents sent me to a Jesuit high school where I was the only Hindu student and graduated as valedictorian in 2003. I then went to Harvard to study molecular biology and finished near the top of my class. Rather than becoming an academic scientist, I joined a large hedge fund in 2007 and started investing in biotech. A few years later I became the youngest partner at the firm.

In 2010, I had an itch to study law, so I went to Yale while keeping my job at the fund. After law school, I started a biotech company called Roivant Sciences. My goal was to challenge big pharma’s bureaucracy with a new business model—which proved to be easier said than done. I started by developing a drug for Alzheimer’s disease that resulted in the largest biotech IPO in history at the time, though a few years later that drug failed spectacularly. Failure hurt, and I was chastened by it. Thankfully the company went on to develop important drugs for other diseases that helped patients in the end. I’ve also co-founded a few tech companies along the way, one that I sold in 2009 and another of which is fast-growing today, and now I’m philanthropically active in a number of nonprofit ventures. I know how the elite business world works—and elite academia and philanthropy too—because I’ve seen it firsthand.

I used to think corporate bureaucracy was bad because it’s inefficient. That’s true, but it’s not the biggest problem. Rather, there’s a new invisible force at work in the highest ranks of corporate America, one far more nefarious. It’s the defining scam of our time—one that robs you of not only your money but your voice and your identity.

The con works like a magic trick, summed up well by Michael Caine’s character in the opening monologue in Christopher Nolan’s movie The Prestige:

Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called The Pledge. The magician shows you something ordinary: a deck of cards, a bird or a man. . . . The second act is called The Turn. The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough; you have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call The Prestige.1

Financial success in twenty-first-century America involves the same simple steps. First, the Pledge: you find an ordinary market where ordinary people sell ordinary things. The simpler, the better. Second, the Turn: you find an arbitrage in that market and squeeze the hell out of it. An arbitrage refers to the opportunity to buy something for one price and instantly sell it for a higher price to someone else.

If this were a book about how to get rich quick, I’d expound on these first two steps. But the point of this book is to expose the dirty little secret underlying the third step of corporate America’s act, its Prestige. Here’s how it works: pretend like you care about something other than profit and power, precisely to gain more of each.

All great magicians master the art of distraction—flashing lights, smoke, beautiful women on stage. Today’s captains of industry do it by promoting progressive social values. Their tactics are far more dangerous for America than those of the older robber barons: their do-good smoke screen expands not only their market power but their power over every other facet of our lives.

As a young twenty-first-century capitalist myself, the thing I was supposed to do was shut up and play along: wear hipster clothes, lead via practiced vulnerability, applaud diversity and inclusion, and muse on how to make the world a better place at conferences in fancy ski towns. Not a bad gig.

The most important part of the trick was to stay mum about it. Now I’m violating the code by pulling back the curtain and showing you what’s really going on in corporate boardrooms across America.

Why am I defecting? I’m fed up with corporate America’s game of pretending to care about justice in order to make money. It is quietly wreaking havoc on American democracy. It demands that a small group of investors and CEOs determine what’s good for society rather than our democracy at large. This new trend has created a major cultural shift in America. It’s not just ruining companies. It’s polarizing our politics. It’s dividing our country to a breaking point. Worst of all, it’s concentrating the power to determine American values in the hands of a small group of capitalists rather than in the hands of the American citizenry at large, which is where the dialogue about social values belongs. That’s not America, but a distortion of it.

Wokeness has remade American capitalism in its own image. Talk of being “woke” has morphed into a kind of catchall term for progressive identity politics today. The phrase “stay woke” was used from time to time by black2 civil rights activists over the last few decades, but it really took off only recently, when black protestors made it a catchphrase in the Ferguson protests in response to a police officer fatally shooting Michael Brown.3

These days, white progressives have appropriated “stay woke” as a general-purpose term that refers to being aware of all identity-based injustices. So while “stay woke” started as a remark black people would say to remind each other to be alert to racism, it would now be perfectly normal for white coastal suburbanites to say it to remind each other to watch out for possible microaggressions against, say, transgender people—for example, accidentally calling someone by their pre-transition name. In woke terminology, that forbidden practice would be called “deadnaming,” and “microaggression” means a small offense that causes a lot of harm when done widely. If someone committed a microaggression against black transgender people, we enter the world of “intersectionality,” where identity politics is applied to someone who has intersecting minority identities and its rules get complicated. Being woke means waking up to these invisible power structures that govern the social universe.

Lost? You aren’t alone. Basically, being woke means obsessing about race, gender, and sexual orientation. Maybe climate change too. That’s the best definition I can give. Today more and more people are becoming woke, even though generations of civil rights leaders have taught us not to focus on race or gender. And now capitalism is trying to stay woke too.

Once corporations discovered wokeness, the inevitable happened: they used it to make money.

Consider Fearless Girl, a statue of a young girl that suddenly appeared one day in New York City to stare down the iconic statue of the Wall Street bull. It was apparently a challenge for Wall Street to promote gender diversity: the placard at Fearless Girl’s feet said, “Know the power of women in leadership. SHE makes a difference.” Feminists cheered. The trick? “SHE” referred not only to Fearless Girl but to the Nasdaq-listed exchange-traded fund (ETF) that her commissioners, State Street Global Advisors, wanted people to buy. State Street was battling a lawsuit from female employees saying it paid them less than their male peers in the firm. Fearless Girl was a line item in an advertising budget.

But it’s not enough to spend money on a PR trick. No capitalist would applaud yet. You have to bring the money back. For its final act, its Prestige, State Street is suing the statue’s creator, Kristen Visbal, saying that by making three unauthorized reproductions of Fearless Girl Visbal damaged State Street’s global campaign in support of female leadership and gender diversity. A master class on the trick itself. Some feminists still adore Fearless Girl. I doubt many of them know about her ETF or the fees State Street charges on it. She now stands guard across from the New York Stock Exchange. Yes, SHE makes a difference—to the bottom line.

An essential part of corporate wokeness is this jujitsu-like move where big business has figured out that it can make money by critiquing itself. First, you start praising gender diversity. Next, you criticize Wall Street’s lack of it, even though you’re Wall Street. Finally, Wall Street somehow gets to be the leader in the fight against big corporations. It gets to become its own watchman and, even better, get paid to do it.

Sincere liberals get tricked into adulation by their love of woke causes. Conservatives are duped into submission as they fall back on slogans they memorized decades ago—something like “the market can do no wrong”—failing to recognize that the free market they had in mind doesn’t actually exist today. And poof! Both sides are blinded to the gradual rise of a twenty-first-century Leviathan far more powerful than what even Thomas Hobbes imagined almost four centuries ago.

This new woke-industrial Leviathan gains its power by dividing us as a people. When corporations tell us what social values we’re supposed to adopt, they take America as a whole and divide us into tribes. That makes it easier for them to make a buck, but it also coaxes us into adopting new identities based on skin-deep characteristics and flimsy social causes that supplant our deeper shared identity as Americans.

Corporations win. Woke activists win. Celebrities win. Even the Chinese Communist Party finds a way to win (more on that later). But the losers of this game are the American people, our hollowed-out institutions, and American democracy itself. The subversion of America by this new form of capitalism isn’t just a bug; as they say in Silicon Valley, it’s a feature.

This is a book that exposes exactly how this disaster unfolded and tells us what we can do to stop it. I’m not a journalist reporting on my research findings. This is the stuff I’ve encountered firsthand over the last 15 years in academia and in business. I’ve seen how the game is played. Now I’m taking you behind the curtain to show you how it works.

In the early chapters of this book, I reveal how the woke-industrial complex fleeces you of your money. Later, I expose how big business, dishonorable politicians at home, and autocratic dictators abroad collude to rob you of your voice and your vote in our democracy. Under the banner of “stakeholder capitalism,” CEOs and large investors work with ideological activists to implement radical agendas that they could never pass in Congress. Finally, I reveal how these actors consummate the most pernicious heist of all: they steal our shared American identity. Woke culture posits a new theory of who you are as a person, one that reduces you to the characteristics you inherit at birth and denies your status as a free agent in the world. And it deploys powerful corporations to propagate this new theory with the full force of modern capitalism behind it.

The antidote isn’t to fight wokeness directly. It can’t be, because that’s a losing battle. You’ll be canceled before you even stand a chance. The true solution is to gradually rebuild a vision for shared American identity that is so deep and so powerful that it dilutes wokeism to irrelevance, one that no longer leaves us susceptible to being divided by corporate elites for their own gain. The modern woke-industrial complex preys on our innermost insecurities about who we really are as individuals and as a people, by mixing morality with commercialism. That might make us better consumers in the short run, but it leaves us worse off as citizens in the end. Banning bad corporate behavior isn’t the ultimate answer. Rather, the answer is to do the hard work of rediscovering who we really are.

Earlier this year, writing this book forced me to rediscover who I was.

On January 6, 2021, an angry mob of rioters stormed the US Capitol as Congress convened to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election. It was a disgrace, and it was a stain on our history. When I watched it, I was ashamed of our nation. It made me want to be a better American.

But I grew even more worried about what happened after the Capitol riot. In the ensuing days, Silicon Valley closed ranks to cancel the accounts of not only the people who participated in that riot but everyday conservatives across the country. Social media companies, payment processing companies, home rental companies, and many more acted in unison. It was a Soviet-style ideological purge, happening in plain sight, right here in America, except the censorship czar wasn’t big government. It wasn’t private enterprise either. Rather it was a new beast altogether, a frightening hybrid of the two.

As a citizen, I couldn’t stomach it. I argued in The Wall Street Journal, along with my former law professor, that companies like Twitter and Facebook are legally bound by the First Amendment and that they break the law when they engage in selective political censorship.4 That’s because Big Tech companies, unlike ordinary publishers, are the beneficiaries of a special federal law that protects them in certain ways but also obligates them to abide by the Constitution.

I couldn’t anticipate what followed. Two advisors to my company resigned immediately. “Please immediately remove my name from all internal and public materials reporting or implying an association with Roivant or any of its subsidiary and affiliated entities,” one of them wrote. “I am submitting my resignation, effective immediately,” another wrote to me. “I was raised to value social justice causes and efforts for the greater good above all others.” A third advisor texted me saying, “I am profoundly disappointed . . . your comments on right wing media have been deeply troubling.”

It wasn’t just my advisors. Close friends called me to say how disappointed they were. One of them pleaded with me on the phone: “My friends have made money by investing in your company. Don’t ruin it for them.” One of my former executives, her eyes filled with tears, said, “Vivek, I had such high hopes for you. What happened?” Many of my employees were upset too, even as some of them privately emailed me to say they agreed with me.

Yet there was a peculiarity about it too. Eight months earlier, my advisors and friends were impatient with me for a different reason. Following the tragic death of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in the spring of 2020, they pressured me to do more to address systemic racism. They felt I hadn’t done enough to condemn it. Apparently, being a CEO required me to speak out about politics sometimes, yet other times it required me to stay silent.

As CEO, I needed to effectively run a business focused on developing medicines without getting intertwined in political matters. Yet as a citizen, I felt compelled to speak out about the perils of woke capitalism. I tried my best to avoid using my company as a platform to foist my views onto others. But eventually I had to admit that I couldn’t do justice to either while trying to do both at once.

So in the end I decided to practice what I preached. It wasn’t easy, but in January 2021, I stepped down as CEO of my own company, seven years after I founded it, and gave the job to the person who was most qualified to do it—our longtime CFO, whose political perspectives couldn’t be more different from my own. He’s liberal. He’s also brilliant. On the day I appointed him, I said that he would speak for the company going forward, and I meant it.

There was a certain irony to the decision that lingered with me. When left-leaning CEOs like Marc Benioff write books about their views on business and politics, it doesn’t hurt their companies at all. Rather, it seems to help them. But my situation was different. At the company townhall explaining my decision to step down, I said that it was important to separate my personal voice as a citizen from the voice of the company in order to protect the company. No one was confused.

I do think there’s a double standard at play in America, but ultimately I didn’t step aside because I feared a firestorm. I did it because my own beliefs told me I had to keep business and politics apart.

A good barometer for the health of any democracy is the percentage of people who are willing to say what they actually believe in public. As a nation, we’re doing pretty poorly on that metric right now, and the only way to fix it is to start talking openly again. I wasn’t free to do that as a CEO, but now I am as an ordinary citizen. I hope some of you will find what I have to say worthwhile.

CHAPTER 1

The Goldman Rule

IN ONE OF MY FAVORITE EPISODES of South Park, two sleazy salesmen try to sell shoddy vacation condos in the glitzy ski town of “Asspen” to the lower middle-class residents of South Park. Their sales pitch is simple: “Try saying it, ‘I’ve got a little place in Asspen.’ Rolls off the tongue nicely, doesn’t it?” Eventually, the residents open up their checkbooks.1

This is exactly what happened when recruiters from Goldman Sachs used to show up on Ivy League campuses in the early 2000s. You didn’t join Goldman as a summer intern for the $1,500-per week-paycheck, though that wasn’t bad. Or for the possibility of a $65,000-a-year full-time offer for a 100-plus-hour-a-week job. You did it for the privilege of saying: “I work at Goldman Sachs.” There was something intoxicating about working at the most elite financial institution in America. For analysts who worked for Goldman in its day, the rush you got from saying you worked there was the equivalent of how today’s graduates feel when they say they work for a “social impact fund” or a “cleantech startup in the Valley.”

In the spring of 2006, I was a 20-year-old junior at Harvard College, and I fell for the trick. I joined Goldman Sachs that summer as an intern.

By the end of June, I knew that I had made a terrible mistake. People walked around Goldman Sachs with polished black leather shoes, pressed shirts, and Hugo Boss ties. I was selected to work in the firm’s then-prestigious investment division, where the essence of the job wasn’t so different from what my boss at a hedge fund had explained to me the prior year: to turn a pile of money into an even bigger pile of money. Yet at Goldman, we carried out that mission in a more genteel way. The managing directors at Goldman—the bosses at the top of the food chain—wore cheap digital watches with black rubber wrist straps, prominently juxtaposed against their expensive tailor-made dress shirts. It was an unspoken Gold-man tradition.

One of the many vice presidents who worked in the cubicle diagonally across from mine would make a small scene every time he needed to use the restroom, dashing out and walking fast to and from his desk, just to show everyone how busy he was. I was the only one with a direct view of his computer screen; he was usually surfing different news sites on the web. Six weeks into the internship, I hadn’t learned a single thing—save for the polite suggestion from my superiors that I wear nicer shoes to the office.

The hallmark event at Goldman Sachs the summer I worked there wasn’t a poker tournament on a lavish boat cruise followed by a debauched night of clubbing, as it had been at the more edgy firm where I’d worked the prior summer. Rather, it was “service day”—a day that involved dressing up in a T-shirt and shorts and then dedicating time to serving the community. Back in 2006, that involved planting trees in a garden in Harlem. The co-head of the group at the time was supposed to lead the way.

I welcomed the prospect of a full day spent at a park away from Goldman’s cloistered offices. Yet when I showed up at the park in Harlem, very few of my colleagues seemed interested in . . . well, planting trees. The full-time analysts shared office gossip with the summer analysts. The vice presidents one-upped each other with war stories about investment deals. And, of course, the head of the group was nowhere to be found.

It was supposed to be an all-day activity, yet after an hour I noticed that very little service had actually been performed. As if on cue, the co-head of the group showed up an hour late—wearing a slim-fit suit and a pair of Gucci boots. The chatter among the rest of the team died down, as we awaited what he had to say.

“Alright, guys,” he said with a somber expression, as though he were going to discipline the team. A moment of tension hung in the air. And then he broke the ice: “Let’s take some pictures and get out of here!” The entire group burst into laughter. Within minutes we had vacated the premises. No trees had been planted. Within a half hour, the entire group was seated comfortably at a nearby bar that was well prepared for our arrival—pitchers of beer ready on the tables and all.

I turned to one of the younger associates sitting next to me at the bar. I remarked that if we wanted to have a “social day,” then we should’ve just called it that instead of “service day.”

He laughed and demurred: “Look, just do what the boss says.” Then he quipped back: “You ever heard of the Golden Rule?”

“Treat others like you want to be treated,” I replied.

“Wrong,” he said. “He who has the gold makes the rules.”

I called it “the Goldman Rule.” I learned something valuable that summer after all.

NEARLY A DECADE and a half after I learned that whoever has the gold makes the rules, the Goldman Rule had only grown in importance. In January 2020, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon declared that Goldman would refuse to take companies public unless they had at least one “diverse” member on their board. Goldman didn’t specify who counted as “diverse,” other than to say that it had a “focus on women.” The bank just said that “this decision is rooted first and foremost in our conviction that companies with diverse leadership perform better” and that board diversity “reduces the risk of groupthink.”

Personally, I believe the best way to achieve diversity of thought on a corporate board is to simply screen board candidates for the diversity of their thoughts, not the diversity of their genetically inherited attributes. But that wasn’t what bothered me most about Goldman’s announcement. The bigger problem was that its edict wasn’t about diversity at all. It was about corporate opportunism: seizing an already popular social value and prominently emblazoning it with the Goldman Sachs logo. This was just its latest version of pretending to plant trees in Harlem.

The timing of Goldman’s announcement was telling. In the prior year, approximately half the open board seats at S&P 500 companies went to women. In July 2019, the last remaining all-male board in the S&P 500 appointed a woman. In other words, every single company in the S&P 500 was already abiding by Goldman’s diversity standard long before Goldman issued its proclamation. Goldman’s announcement was hardly a profile in courage; it was just an ideal way to attract praise without taking any real risk. Another great risk-adjusted return for Goldman Sachs.

Goldman’s timing was also impeccable in another way. Its diversity quota proclamation stole the headlines from a much less flattering event: Goldman had just agreed to pay $5 billion in fines to governments around the world for its role in a scheme stealing billions from the Malaysian people.2 In what has become known as the 1MDB scandal, Goldman paid more than $1 billion in bribes to win work raising money for the 1Malaysia Development Berhad Fund, which was supposedly meant to fund public development projects. In actuality, Goldman turned a willfully blind eye as corrupt Malaysian officials immediately turned the fund into their own private piggy bank, buying art and jewelry. Some of that money literally ended up funding The Wolf of Wall Street.3

Goldman’s effort to change the narrative didn’t go unnoticed. As one Redditor on the now-infamous forum WallStreetBets observed, “They want to make sure that any IPO they bring to market has a brown or black person on the board of the company they are IPOing, but are perfectly okay with ripping off millions of Malaysians by engineering a slush fund for an oil tycoon’s jewelry collection and private jet.”4,5 Well, yes. Welcome to the woke-industrial complex.

Large banks like Goldman Sachs are particularly adept at playing the woke capitalist game. But in reality, by 2020 it was the prevailing model business in corporate America. Stakeholder capitalism—the trendy idea that companies should serve not just their shareholders but also other interests and society at large—was no longer simply on the rise. It had been crowned as the governing philosophy for big business in America.

At the end of 2018, the Business Roundtable, the top lobbying group for America’s largest corporations, overturned a 22-yearold policy statement that said a corporation’s paramount purpose is to serve its shareholders. In its place, its 181 members signed and issued a commitment to lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders—not only shareholders, but customers, suppliers, employees, and communities. “Multi-stakeholder capitalism is the answer to addressing our challenges holistically,” Walmart CEO and Business Roundtable Chairman Doug McMillon said.6

In the years that followed, the Business Roundtable’s CEO members dutifully recited their new catechism. “We uniquely appreciate the new definition of a corporation and the critical mindset it represents for business,” said Beth Ford, CEO of Land O’Lakes. “The role of business is larger than the already high calling of providing value to those who buy our products and services,” said Scott Stephenson, CEO of Verisk Analytics. “Verisk is an inclusive workplace that values diversity and perspectives.” Of course, “diversity and perspectives” is different from a diversity of perspectives.7 Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment firm, issued an open letter to CEOs describing a “Sustainability Accounting Standards Board” that would tackle issues ranging from labor practices to workforce diversity to climate change. Scores of others followed.

If the turn of the decade was a tipping point, then the murder of George Floyd, a black man, at the hands of a white police officer in May 2020 broke the dam. Companies ranging from Apple to Uber to Novartis issued lengthy statements in support of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. In a surprising about-face, L’Oréal rehired a model it had fired for her comments about “the racial violence of white people.” Well-respected companies like Coca-Cola implemented corporate programs teaching employees “to be less white” and that “to be less white is to be less oppressive, be less arrogant, be less certain, be less defensive, be more humble” and that “white people are socialized to feel that they are inherently superior because they are white.”8 Starbucks said it would mandate anti-bias training for executives and tie their compensation to increasing minority representation in its workforce.

In 2021, the new trend became unstoppable. In response to Georgia’s new voting rules this year, Delta’s CEO declared that “the final bill is unacceptable and does not match Delta’s values,” failing to explain why Americans should care whether a voting law matches the values of an airline company.9 Coca-Cola’s CEO added: “Our focus is now on supporting federal legislation that protects voting access and addresses voter suppression across the country,” a statement that sounded more like that of a Super PAC than a soft drink manufacturer.10 Biotech industry leaders called on CEOs to “actively consider alternatives to investing within states that have enacted voter suppression laws” and to encourage “alternative venues for conferences and major meetings.”11 Hundreds of other companies issued similar statements.

Fifteen years ago, stakeholder capitalism might have represented a challenge to the system. Today, it is the system—and its tolerance for dissent is vanishing. Al Gore recently declared that stakeholder capitalism is “the proven model for business” and that corporate executives who fail to act accordingly could be sued for violating their fiduciary duties.12 Marc Benioff, billionaire founder of Sales force.com, proclaimed that shareholder capitalism is “dead.”13 Politicians on both sides, from Elizabeth Warren to Marco Rubio, have jumped on the bandwagon. Today the case is basically closed. In 2018, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat called this trend “woke capitalism.”14 I call it “Wokenomics”—a new economic model that infuses woke values into big business.

In late 2020, on the 50th anniversary of Milton Friedman’s famous 1970 defense of shareholder capitalism, a few economists made a meek last-ditch attempt to resist this trend by defending “the Friedman Doctrine.” But their arguments were at best persuasive only to other economists accustomed to speaking in the parlance of economic efficiency, lacking the moral sheen of the other side. For example, Harvard economist Greg Mankiw argued in The New York Times that corporate executives are unlikely to be well equipped with the necessary skills to serve society and that there is no “metric” to determine how well executives are serving society as a whole.15 University of Chicago economist Steven Kaplan cited the US auto industry in the 1960s and 1970s as a cautionary tale about stakeholder capitalism: by treating their unions and employees as partners and stakeholders, US automakers significantly underperformed Japanese competitors.16

These economists miss the main point. The real problem with stakeholder capitalism isn’t that it’s inefficient. The deeper threat is this: it’s the Goldman Rule in action. The guys with the gold get to make the rules. Not just market rules, but moral rules too.

Speaking as a former CEO myself, I’m deeply concerned that this new model of capitalism demands a dangerous expansion of corporate power that threatens to subvert American democracy. For corporations to advance social causes, they must first define which causes to prioritize and what position to take. Yet that isn’t a business judgment; it’s a moral one. America was founded on the idea that we make our most important value judgments through our democratic process, where each citizen’s voice is weighted equally, rather than by a small group of elites in private. Debates about our social values belong in the civic sphere, not in the corner offices of corporate America.

I’d love to hear Larry Fink’s favorite stock picks, but as a citizen I don’t particularly care for his views on racial justice or environmentalism. Democratically elected officeholders and other public leaders, not CEOs and portfolio managers, should lead the debate about what values define America. Business leaders are supposed to decide how much to spend on a manufacturing plant or whether to invest in one piece of technology or another—not whether a minimum wage is more important for society than full employment or whether reducing America’s carbon footprint is more important than the geopolitical consequences of doing so. CEOs are no better suited to make these decisions than an average politician is to, say, make the R&D decisions of a pharma company.

To be clear, that doesn’t mean that citizens, including CEOs, should refrain from speaking up strictly in their personal capacities. Corporations may not be people, but CEOs definitely are, and it’s a good thing when citizens personally engage on civic issues. But there’s a difference between speaking up as a citizen and using your company’s market power to foist your views onto society while avoiding the rigors of public debate in our democracy. That’s exactly what Larry Fink does when BlackRock issues social mandates about what companies it will or won’t invest in or what Jack Dorsey does when Twitter consistently censors certain political viewpoints rather than others. When companies use their market power to make moral rules, they effectively prevent those other citizens from having the same say in our democracy.

Curiously, today the most ardent supporters of stakeholder capitalism are liberal. Many progressives who love stakeholder capitalism abhor the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission because it permits corporations to donate to political campaigns and influence electoral outcomes. Al Gore, one of the principal proponents of stakeholder capitalism, has described this ruling as “obscene” and proposed overturning it through a constitutional amendment.17 Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama have all made similar comments.

Yet stakeholder capitalism is Citizens United on steroids. It not only permits corporations to influence our democracy, it demands that they do that by advancing whatever social values they choose. Ironically, those who most vehemently proclaim that “corporations aren’t people” are the ones who now demand that corporations act more like, well, people.

Advocates of stakeholder capitalism say it’s totally consistent to oppose corporate contributions to political campaigns while still demanding that corporate leaders pursue social agendas that are good for society at large. Yet this argument ignores why it’s bad for corporations to influence elections in the first place. It’s not just the election that matters, but what the election symbolizes: the idea that every person’s vote counts equally in our democracy. That’s what’s special about an election. That’s what makes capitalist influence over elections so troubling—because when dollars mix with votes, everyone’s vote no longer counts equally. When they pick which politicians to support, they’re just pursuing their self-interest, and it’s no different when they pick which “social goals” to prioritize too. Either Al Gore doesn’t understand that, or else his new business interests as an ESG investor make that an inconvenient truth.

The damage to democracy is further-reaching. The heart of our democracy isn’t just about casting a ballot in November. Rather, it’s about preserving democratic norms in everyday life, including free speech and open debate. When companies make political proclamations, employees who personally disagree with the company’s position face a stark choice: speak up freely and risk your career, or keep your job while keeping your head down. That isn’t how America is supposed to work, yet that is a reality for many Americans today.

Even worse, partisan politics is now infecting spheres of our lives that were previously apolitical. Our social fabric depends on preserving certain spaces as apolitical sanctuaries, especially in an increasingly divided polity like ours. Until earlier this year, Major League Baseball used to offer one of those rare sanctuaries: fans were bound together by their love of baseball—whether black or white, Democrat or Republican. Thanks to the MLB’s dramatic protest of Georgia’s new voting rules earlier this year, that sanctuary has vanished.

Democracy loses twice: corporate influence pollutes the public debate about moral questions, and social solidarity is eroded as apolitical institutions slowly disappear. Stakeholder capitalism poisons democracy, partisan politics poisons capitalism, and in the end we are left with neither capitalism nor democracy.

In practice, liberals love stakeholder capitalism only insofar as companies advance social goals that they personally find appealing. Most liberals dislike the Supreme Court’s ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores for permitting a corporation to limit health insurance coverage of certain contraceptives for its employees. But they cheered when Goldman Sachs issued its diversity edict for American companies that want to pursue an IPO. At core, Goldman’s diversity edict is Hobby Lobby on steroids too. Hobby Lobby is a family-owned arts and crafts store whose policy applies to its own employees, whereas Goldman’s quota system applies effectively to every public company in America. If liberals dislike Hobby Lobby on principled grounds, they should shudder at the raw societal power exercised by behemoths like Goldman Sachs.

Wokenomics is crony capitalism 2.0, and here’s how it works: big business uses progressive-friendly values to deflect attention from its own monolithic pursuit of profit and power. Crony capitalism 1.0 was straightforward by comparison: corporations simply had to make campaign contributions to legislators in return for favorable legislative treatment. Here’s an example: big Wall Street banks hire lobbyists to exert influence in Washington, and in return they get favorable regulations that codify their status as gatekeepers who enjoy oligopoly status in taking companies public. The regulations are so complex and onerous that they prevent upstart competitors from getting in on the action, keeping the oligopoly intact. Championship-level players of this game like Goldman Sachs top it off with a flourish, by lending their executives to serve as US treasury secretaries (Steve Mnuchin under President Trump, Hank Paulson under President George W. Bush, and so on). And it pays off in the end: winners like Goldman Sachs get bailouts in tough times like 2008, while less adroit competitors like Lehman Brothers are hung out to dry by Hank Paulson. That much is simple enough.

But crony capitalism 2.0 is far trickier. It uses a different playbook from that used by version 1.0—one that’s designed to escape public notice. In January 2020, when David Solomon, first issued the Goldman’s diversity proclamation at the World Economic Forum in Davos, it was at a time when Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two of the biggest critics of the US government’s 2008 bailout of Goldman Sachs, were presidential frontrunners. Having supplicated to the swamp uni-party of crony Republicans and centrist Democrats for decades, the moment had arrived for Goldman Sachs to begin placating the identity-politics-obsessed far left, just as that wing of the Democratic party had begun to accrue greater political power. Their new CEO is woker than woke, and he’s a DJ on the side too. That’s how the 2020 edition of crony capitalism looks; Hank Paulson is outmoded by comparison.

TO BE SURE, many CEOs who promote stakeholder capitalism do it genuinely. Ken Frazier, the former chairman and CEO of Merck, is a pharma industry leader I greatly admire for his company’s accomplishments in the treatment of cancer and other diseases. In 2020, he publicly declared that it’s important for businesses like Merck to “stabilize society” amid rising economic inequity and racial injustice, saying it was time for “industry to step up to the plate.” In a public interview in October 2020, he said: “What makes me worry ultimately is when people don’t believe in our institutions, they don’t believe in our system, they don’t believe there’s fundamental fairness, then I think our society begins to come apart.”18 Earlier in 2021, Ken was one of corporate America’s most powerful voices against Georgia’s new voting rules.19

Having met Ken myself, I can attest that he truly believes these things. He’s an authentic leader; several employees at my company who used to work for Merck truly revere him. Merck is also a fundamentally different company from Goldman Sachs: its employee base is motivated by improving patient care rather than by the number of green pieces of paper that end up in their bank account at the end of bonus season. Personally, I don’t necessarily think that one of those is inherently better than the other, though they are fundamentally different.

But Ken misses the point that his own acts, however well intentioned, may actually contribute to the public’s loss of faith in our system. Many Americans no longer believe in our institutions precisely because CEOs and other leaders use their institutional seats of power to crowd out the voices of ordinary Americans. When CEOs tell people what they’re supposed to think about moral questions, then people stop believing that their own opinions really matter. In other words, they stop believing in the system.

Ken and I debated this issue in an email exchange last year. He quoted George Merck, his company’s founder, who said that “medicine is for the people, not for the profits,” and asked me whether rejecting stakeholder capitalism means putting profits ahead of patients.

My answer was no. In the long run, the only way for a pharmaceutical company to be successful is by serving patients first. But putting patients first also means putting them ahead of fashionable social causes. It means that we don’t care if the scientist who discovers a cure to COVID-19 is white or black or a man or a woman. It means that we don’t care if the manufacturing and distribution process that delivers cures most quickly to patients is carbon neutral.

Ken may self-identify as liberal, but his view actually reflects conservative European social thought, which was skeptical of democracy and convinced that well-meaning elites should work together for the common good, as long as the common good could be defined by them. In the Old World, that often meant some combination of political leaders, business and labor elites, and the church working together to define and implement social goals. But America was supposed to offer a different vision: citizens defining the common good through the democratic process—publicly through open debate and privately at the ballot box—without elite intervention.

That’s what makes America great. That’s what makes America itself.

But today, with the advent of Wokenomics, we are slowly receding back to the pre-American Old World model on the global stage. Even the Vatican is getting in on the act. In December 2020, Pope Francis issued an implicit endorsement of stakeholder capitalism by launching a “Council for Inclusive Capitalism” in partnership with the Vatican. The council “boasts over $10.5 trillion in assets under management, companies with over $2.1 trillion of market capitalization, and 200 million workers in over 163 countries.”20 This council endorses not only equality of opportunity but also “Equitable Outcomes’’ and “Fairness Across Generations on the Environment.” There’s a page on its website dystopically titled “Our Guardians,” which includes a creepy-looking photo of billionaires like Marc Benioff of Salesforce, large corporate CEOs from Wall Street to big pharma, and descendants of the Rothschild banking family in Europe surrounding the Pope and making a pledge to “change capitalism for good.”21 The American vision of separating church from state, and democracy from capitalism, has been supplanted by this new global vision of mixing them all with one another—leaving us with none of them in the end.

In 2019, I attended a closed-door forum hosted by J.P. Morgan for a select group of startup company founders. It was the first time I’d been invited to join their ranks, so I attended with curiosity. Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan, spoke to the audience during dinner. Another CEO asked him: “Would you ever consider running for president?” Dimon didn’t miss a beat: “I would love to be president. I just don’t like the idea of running for president.” The audience laughed—not because it was obviously outlandish, but because it was obviously true.

Dimon couldn’t have better summarized the motives of many CEOs who embrace stakeholder capitalism: it allows them to exercise quasi-political power without having to go through the hassle of getting elected. Yet that hassle is part and parcel of democracy itself.

Jamie Dimon probably won’t ever get to be president. But by being CEO of one of the largest banks, in today’s world he still gets the social platform that he craves. Following George Floyd’s death last summer, Dimon broadcast a video of himself dramatically kneeling in his office to demonstrate his solidarity with the protesters in the street. He was widely praised for doing so. I couldn’t help but be amused. In a prior century, the founder of J.P. Morgan—John Pierpont Morgan—had once famously stated: “I owe the public nothing.” He was hated in his day. Jamie Dimon wasn’t quite as rich as John Piermont Morgan, but he had learned that if you claim to owe the public everything, you will in fact owe it nothing.

Many Americans have justifiably lost faith in government yet still recognize that we need to solve important social problems. If government has failed us, then someone else needs to step up. And if that’s big business, then so be it, right?

I think not. Admittedly, our democracy today is a far cry from the ideal that our Founding Fathers envisioned. But we owe it to ourselves to do the messy work of fixing our democracy from within rather than delegating that hard work to self-interested corporate leaders. Our democracy is messy for the same reason that it is beautiful: we often disagree with our fellow citizens about our most pressing social questions. Our mechanism for dealing with those disagreements is through public debate in our civic institutions, not corporate fiats issued from the mountaintops of Davos.

The crux of our concern about capitalism shouldn’t be that companies serve their shareholders exclusively. That’s just what capitalism is. Rather, our concern should be that capitalism has begun to pollute our democracy through the influence of dollars on our political system—and it’s done so in more ways than one. The right answer isn’t to force democracy and capitalism to share the same bed.

What we really need is social distancing between the two . . . to prevent each from infecting the other.

IN PRINCIPLE, “STAKEHOLDER capitalism” can mean one of two things. It could mean that corporations should affirmatively take steps toward addressing important societal issues like climate change, racism, and workers’ rights. That’s the bandwagon that most companies are jumping on these days—committing capital to fight climate change, making donations to BLM, conducting mandatory training sessions for employees on how to be “anti-racist,” and so forth. That’s where my criticism in this book is focused. This trend has taken corporate America by storm in recent years and threatens to subvert the integrity of American democracy.

But there’s a more sympathetic version of the same idea that refers to something much simpler—namely, the idea that executives should just account for the negative externalities, or unintended consequences, of their actions before making important business decisions. That just means they should avoid hurting people. We all have a basic moral duty not to hurt others, and we don’t lose it when we band together and start calling ourselves corporations, the argument goes.

Think of a tobacco company that might face a choice about whether to include an ingredient that makes its product more addictive, in a way that leaves both consumers and society worse off. If a company knows that its product will harm people but there’s no technical legal prohibition on selling it, the “negative-externality” folks argue that the company should still exercise restraint even though the profit-maximizing course of action is to sell as much of the product as possible.

I acknowledge that’s a hard case. In theory, it raises a dilemma for my argument. But in actuality this kind of case rarely arises in the real world: most corporate actions that are known to harm people are either illegal or likely to hurt the company’s reputation—and profits—in the long run. During my seven years as a biopharmaceutical CEO, I never once had to make that kind of choice: our company’s commitment to long-term value meant that it was never in our interest to harm people. We made medicines, not cigarettes.

Regardless of where you land on those hard cases, my point is this: a tobacco company’s decision to include ingredients that are less addictive in its cigarettes is fundamentally different from that same company writing a check to BLM or mandating anti-racist employee training about how “to be less white.” The ordinary duty not to hurt people doesn’t require corporations to reshape the world into their vision of utopia.

Many sincere woke activists resist that distinction—and that’s the root of our disagreement. According to their view, capitalism itself systematically rewards, say, white people over black people. That inequity is a negative externality of the very capitalist system that makes corporations possible, according to them. So any company that benefits from America’s capitalist system is therefore contributing to systemic racism—and is obligated to fix it. According to this view, Marlboro should write a check to BLM for the exact same reason that it’s obligated to include less addictive ingredients in its cigarettes.

The sometimes-blurry line between actively doing good and merely avoiding doing harm is one of those iconic debates in moral philosophy, and it reveals an important point about my disagreement with sincere woke capitalists. Our dispute comes down to this: they think they’re morally obliged to minimize the harm that they already do just by “being capitalists,” whereas I think they’re overstepping their authority by trying to affirmatively enact their own conception of the good by using their market power. I think they’re trying too hard to save the world; they think they’re just trying not to make it worse.

But they are making it worse. Even if they’re right that the American system harms some groups, the burden of remedying that harm falls on the American people, and the American people should decide what to do about it democratically. It is not a CEO’s duty to shoulder America’s responsibilities; in reality, that just causes new problems. I believe even honest woke capitalists fail to see how much additional harm they do to American democracy when business elites tell ordinary Americans what causes they’re supposed to prioritize. In my view, this represents a new negative externality that must be weighed by any corporate leader who actually wants to do the right thing.

So that’s my disagreement with sincere woke capitalists. But my bigger beef is with the insincere woke capitalists. Here’s what the sincere guys miss: when they create a system in which business leaders decide moral questions, they open the floodgates for all their unscrupulous colleagues to abuse that newfound power. And there are far more CEOs who are eager to grab money and power in the name of justice than there are CEOs who are agnostic to money and power and care only about justice.

Under the guise of doing good, the corporate con artists hide all of the bad things that they do every day. Coca-Cola fuels an epidemic of diabetes and obesity among black Americans through some of the products it sells. The hard business decision for the company to debate is whether to change the ingredients in a bottle of Coke. But instead of grappling with that question, Coca-Cola executives implement anti-racism training that teaches their employees “to be less white,” and they pay a small fortune to well-heeled diversity consultants who peddle that nonsense. That’s the Goldman playbook. It’s not by accident; it’s by design.

So the “I’m just trying not to hurt anyone” version of stakeholder capitalism inadvertently provides intellectual cover for the real poison at the heart of modern Wokenomics. In the real world, very few American companies are able to harm people over the long run while still making sustainable profits—because the public holds them accountable over time, through both market mechanisms and democratic accountability. But now the rise of woke capitalism creates a decoy that prevents those corrective mechanisms from working as they should. It’s the equivalent of tampering with a smoke detector in the airplane lavatory—which is a federal crime because it risks hurting people.

Some of my fellow CEOs make thoughtful arguments in response. I recently caught up with Nick Green, a former college classmate of mine, who leads Thrive Market, a very successful healthy lifestyle company in California. We’re good friends (we even invested in each other’s companies), but we disagree about stakeholder capitalism. Nick argues that stakeholder capitalism “works” because consumers are demanding more of companies. Consumers want to buy things from companies who share their values. And often that means supporting social causes that their consumers care about. What’s wrong if companies just do what consumers want them to do? Isn’t that what capitalism is all about?

Nick is a great CEO. He built a thriving enterprise from scratch. Each dollar that I invested in his company a few years ago is now worth nearly a hundred. So if he has something to say about building great companies, then he has my attention.

After reflecting on Nick’s comments, I realized that practitioners of stakeholder capitalism come in a few different forms, each of which raises unique issues. First, there are woke executives, who use their positions as corporate managers to advance a particular social agenda. This is fraught with principal-agent conflicts. An agent is supposed to represent a principal. For example, a lawyer is an agent, and his client is the principal. A principal-agent conflict arises when the agent has different interests from the principal—for example, if the lawyer stands to make more money if the client loses her case. In the case of a company, the principal is the company’s shareholder base, and the CEO is the agent. Often, the CEO has an interest in using the company to maintain his personal brand, often at the expense of the company’s shareholders. Here, the main victims are the company’s shareholders.

That’s distinct from the phenomenon of woke investors, who demand that otherwise humdrum CEOs use their companies to advance certain pet social causes favored by the investors themselves. This isn’t the agent betraying the interests of the principal, but the principal (a shareholder) demanding exactly what the agent (the CEO) should do. Effectively, this is what ESG investing is all about. But it’s not just ESG investors who play this game. Sometimes these activist investors include sovereign nations and autocratic dictatorships like China who have their own ideas about what causes to advance.

Woke executives and woke investors raise distinct problems that I address later in the book, but at core they’re both examples of this form of paternalism. In both cases, it’s about business elites telling ordinary Americans what they’re supposed to do and how they’re supposed to think. Each presents an equal affront to American democracy. My critique is mostly directed at this top-down elitism.

But my friend Nick is talking about a third, distinct phenomenon in which woke consumers are the ones who demand that companies drive social change. That’s what I call “woke consumerism.” That isn’t a top-down phenomenon. It’s a grassroots, bottom-up demand that consumers make upon companies. For example, in 2020 many consumers boycotted Goya Foods following its CEO’s praise of President Trump. This isn’t a new trend; back in 2012, consumers turned on Chick-fil-A after its CEO made anti-same-sex marriage comments. That’s different from top-down elitism, and it raises unique issues of its own. Woke consumerism is real. It divides us as a people and weaponizes buying power to stifle authentic debate. And there’s no easy fix, since we live in a free country and people still get to do what they want.

Fundamentally, it’s a cultural problem that demands a cultural solution, one that neither business nor law can provide. But woke consumerism is not nearly as big of a phenomenon as CEOs and investors claim. The idea that “consumers are demanding it and we’re just giving them what they want” is often just a hollow excuse to justify top-down power-grabbing by influential executives and investors. Very few retail “mom-and-pop” investors in the stock market choose a BlackRock mutual fund over one from Fidelity based on the social values it adopts. They make their choices on the basis of investment performance, fees, or the warm smile of a financial broker.

In reality, companies like BlackRock, and in particular their leaders, are using social causes as a way of assuming their place in a moral pantheon. And in the process, they’re quietly dropping hints to consumers to take the bait and make purchasing decisions on the basis of moral qualia rather than product attributes alone. And many consumers then do it, especially when they’re feeling lost and hungry for a purpose, as so many Americans do today. It’s like the equivalent of Virginia Slims targeting insecure teenagers with catchy cigarette ads in the 1990s. Woke consumerism is born when woke companies prey on the insecurities and vulnerabilities of their customers by deflecting our focus away from the price and quality of their products. As it turns out, morality makes for a great marketing tactic. Just ask Fearless Girl. SHE will tell you what to buy.

BEFORE THE 2008 financial crisis, “capitalist excess” took the form of lavish spending on oft-inappropriate entertainment: strip clubs, “dwarf-tossing” from private yachts, chartered jets to the Super Bowl, and so on, all funded by the corporate Amex card.

I had a front-row seat to capitalist excess during my first corporate internship—one that I did in 2005, the year before my internship at Goldman Sachs. That summer I worked at a hedge fund called Amaranth. The little-known investment firm had held a campus recruiting event at Harvard in the fall of 2004, and I’d shown up because the company had offered a free dinner at a fancy restaurant. Amaranth had hired a team of doctors and scientists who professionally evaluated biotech stocks. It sounded pretty cool to me, so I decided to give it a try.

The most valuable lesson I learned that summer was to understand the essence of what it meant to pursue pure wealth for its own sake. The firm’s founder, Nick Maounis, graciously spent time with the summer interns during lunch sessions. He explained with disarming clarity that the purpose of a hedge fund was “to turn a pile of money into an even bigger pile of money” and “to get paid a lot for doing that.” It sounded simple. Even honest. I asked him: “What’s the main goal of your career?” He thought about it deeply in silence and then answered: “To be a billionaire. And also to own a sports team.”

Sadly, Maounis never achieved either goal because Amaranth famously imploded the following year. It used complicated tactics to corner the market for natural gas, which proved to be a profitable strategy in the short run, but the house of cards came tumbling down when the market turned sharply against it. Maounis still left the whole situation a wealthy man because hedge fund managers lock in gains on an annual basis, and even if they lose everyone else’s money, they usually still get to walk away with a good chunk of what they made during the good years. As one colleague explained to me, it wasn’t all that surprising or even that unfair. Every job has its perks. If you’re a nurse, you go home with a few extra latex gloves. If you’re in finance, you go home with a few extra bucks.22 His take was cynical, but there was something self-evident about it too.

But these attitudes can be fraught with potential problems. The most obvious is naked self-dealing. I heard that some corporate executives were able to use the company piggy bank to fund their own lifestyles and tastes through a new model of expense accounting. This kind of thing often led to prosecution. Tyco’s storied CEO Dennis Kozlowski went to jail for “looting” over $600 million from his company to pay for lavish parties, fancy art, and an opulent Manhattan apartment.23 His behavior was different only in degree, not in kind, from some of his peers in that era.

Yet self-dealing wasn’t the biggest problem. Some of these behaviors were questionable; others made for reasonable business strategies to drive profit. By appealing to base and primal human instincts, these companies were able to compete with their peers to attract talented traders, woo lucrative clients, and ultimately do what successful companies do best: make money.