Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

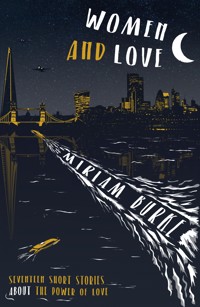

'I couldn't sleep that night; our conversation was like a trapped bird flying around inside my head. The next morning, I texted to say I wouldn't be coming back. I lied about having to return to my country to nurse a sick relative. I couldn't bear to see my story mirrored in his eyes, and to see what we never had. I knew he'd understand.' Women and Love is a thought-provoking collection of seventeen tightly woven tales about the power of love, all its trials and complications, and the shattered lives it can leave in its wake. The stories explore a huge variety of sorts of love surrounding women in wildly differing settings, and features an unforgettable cast including GPs, burglars, inmates, emigrant cleaners, carers, young professionals, and many more. Navigating heavy themes, with a particular focus on LGBTQ+ experiences, including gender dysphoria and searching for a sperm donor, the stories leave the reader burning with indignation, full of empathy and wonder.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Women and Love

miriam burke

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

‘The Existentialist and the Minestrone’ first published in Bookanista in 2020

‘Vincerò’ first published in The Manchester Review in 2019

‘We’re Not Born Here’ first published in The Honest Ulsterman in 2019

‘The Luck of Love’ first published in three parts on fairlightbooks.co.uk in 2018

This collection first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2022

Text © Miriam Burke, 2022

Cover design by Will Dady

Miriam Burke asserts her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental, or is used fictitiously.

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

Contents

Women and Love

The Luck of Love

Things That Matter

The Otherness of People

Vincerò

You Never Really Know

Looking Out

We’re Not Born Here

The Currency of Love

The Unchosen

The Thing About Being Human

Yes, She Said

The Existentialist and the Minestrone

Beyond Love

Falling Together

The Vulnerable Hour

A Splash of Words

Footprints

women and love

The Luck of Love

My mind pulls on any rope that ties it, so I like my job because my mind is free. My clients speak slowly, using simple words, when they talk to me. I’m an emigrant with a PhD in English Literature, but I let them think I’m uneducated and a little stupid.

The Hewitts live in North London, in a big old house with high ceilings, long windows and a garden that has been photographed for a magazine. The carved oak dining-room table came from the refectory of a French monastery and the teak four-poster bed was made in Goa. Mrs Hewitt bid for her furniture at auctions, one piece at a time, and had the damaged pieces restored. She went to artists’ studios with plastic bags full of cash to haggle about the price of the abstract expressionist paintings that cover her walls. Mrs Hewitt loves the house, and everything in it, except her husband. They bought the house when it was a warren of bedsits – she showed me the photos – and she made it beautiful. The house is her life’s work. Everything in her home looks like it cost much more than she paid for it, with the exception of her husband.

Mrs Hewitt worked as a solicitor, helping people buy and sell their homes, which must be a terrible job – boring legal work combined with having to deal with people at their maddest. She got out as soon as she had finished renovating and furnishing the house. Mr Hewitt is a director of a management consultancy firm.

Georgina, their daughter, is thirty years old and lives in her bedroom. She wears a lavender one-piece suit with a fur-trimmed hood, and she has the face of a child on the body of a woman. When Georgina was bullied at school, her parents employed tutors to educate her at home. It is many years since she has felt the sun on her skin. I looked at her search history when I was cleaning her room, and discovered she spends her days following female celebrities: the woman nobody knows spends her life learning about the lives of women everyone knows.

I was cleaning the kitchen cupboards last Monday morning when Mr Hewitt came into the room, dressed in a navy suit that fitted too well to be off the peg. His grey hair was as short as a newly mown lawn and his beard was carefully sculpted. His wife and daughter were sitting at the mosaic table drinking vegetable juice. I am very interested in couples, in how they survive without killing each other or themselves, so I watched and listened.

‘Will you be home for supper?’ asked Mrs Hewitt, without looking at him.

‘I’m not sure.’ He knew this would infuriate her.

Controlling her irritation, she said, ‘I just want to make sure I have enough fish.’

Georgina stared at her father with the loathing her mother was concealing.

‘It depends on whether I have to work late, and that depends on how often I’m interrupted. Can’t you buy enough fish for three and freeze some if I can’t make it?’

‘It’s never as good if you freeze it.’

‘Put my portion in the fridge and I’ll eat it when I get home if I’m late.’

‘You never eat when you come home late. The meal will be thrown out.’

‘Couldn’t you get some steak? That’ll keep.’

‘Georgina doesn’t eat meat any more, and I’m not going to cook two different meals.’

‘I’ll ring as soon as I know what’s happening.’ He didn’t want to give her the pleasure of anticipating his absence.

‘It would make life easier if you made a decision now.’

‘And your life is so hard.’

Mrs Hewitt got up from the table, turned her back on him and started loading the dishwasher. Georgina glared at him and rushed out of the room.

Mr Hewitt felt guilty because he loves his sullen hermit daughter.

‘I’ll ring before eleven to let you know.’

‘I don’t care what you fucking do.’

He walked out the kitchen door, stood at the bottom of the stairs and shouted up: ‘Goodbye, Georgina.’

She didn’t reply.

‘Enjoy your day, Georgina.’

There was no answer.

‘We’re lesbians,’ said Margo, on the first day I met them. ‘If you can’t deal with that, we won’t employ you.’

Every family in my country has an aunt who lives with a special friend, or a cousin who shares his life with a man he met in the army or in a bar. We don’t attach words to it, but we accept them. The English seem to think they invented homosexuality.

‘I’m a composer,’ Margo said. She teaches piano to schoolchildren and she’s been working on an opera for ten years. The opera will never be completed. She wears her hair a little wild and she tilts her head so that she resembles a bust of Beethoven.

Jo is a carpenter and she makes sets for theatre companies. She has short blond hair that stands up on her head and her fine-boned, symmetrical face is a pleasure to look at. She is about twenty years younger than Margo.

They’ve knocked down the internal walls of their small terraced house in South London, and put windows in the roof, and Jo has made fitted furniture for all the rooms, so the house feels much bigger than it is. They can’t afford a cleaner, but they have me once a fortnight because Margo says she can’t take time out from her opera to do her share of the cleaning.

I was defrosting their fridge last Tuesday while they were having a goat’s cheese salad for lunch at the ash breakfast bar in the kitchen. Der Rosenkavalier was playing through their multi-room hi-fi system.

‘Who will we invite round this weekend?’ asked Jo.

‘Do we have to have people every weekend, darling?’ Margo stabbed a cherry tomato with her fork.

‘It’s fun. We work hard, and we need to play. What about Jules and Sylvia?’

Margo looked as if she had a sudden stomach cramp.

‘What does that face mean?’

‘Well, we do see an awful lot of them.’

‘We haven’t seen them for a month!’

‘A month isn’t very long.’

Jo put down the forkful of goat’s cheese that had been on its way to her mouth.

‘They’re close friends. Why don’t you want to see them? I thought you liked them.’

‘I do like them, sweetheart. I just don’t like what they do to you.’

‘Do to me? I don’t understand.’

‘Well, you always get drunk with them and take coke and you’re wiped out for the rest of the weekend.’

‘It’s just a bit of fun. It’s good to let your hair down now and then.’

‘“Now and then” seems to come around quite often… and they’re so vicious about everyone. I can’t imagine we’re spared.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t be surprised if they make fun of us when they visit their other friends. Jules is a great mimic. I sometimes think they only come to see us to get fresh material to entertain their other friends with.’

‘Jules wouldn’t do that to me! We’ve been friends since we were at school.’

‘She doesn’t spare anyone.’

Jo stared down at the rocket leaves on her plate, as if she was asking their advice.

She lifted her head. ‘I’m not going to drop them, if that’s what you want.’

‘It’s not what I want, darling. I’m sorry – I didn’t mean to upset you.’ She reached out her hand and put it on Jo’s.

‘I’m not upset.’

‘All I’m saying is that you might find as you get older that you don’t see so much of some friends because you’ve changed, and you may not have a lot in common any more. When people reach their late twenties they divide into two groups: the ones who continue partying like students, and they usually end up in rehab years later, and those who do something with their lives.’

‘Old friends are the joists in your life – you can’t discard them!’

‘Some joists begin to rot with age, and they’re no longer much support. Have you ever spent an evening with Jules and Sylvia when you haven’t got drunk?’

‘Probably not. But I don’t see why that matters. I have fun with them.’

‘Try it next time they come for dinner; it would be an interesting experiment.’ She skewered a radish that had rolled off her fork.

‘You’ve made your point. You don’t want them to come round, so I won’t invite them.’

‘No, no, do invite them. I don’t want to stop you seeing your friends, sweetheart. I’ll go to bed after the meal and you can stay up having fun with them.’

‘They’ll think you don’t like them if you go to bed early.’

‘They’ll forget about me as soon as I leave the room.’

‘It wouldn’t feel right staying up without you.’

‘I get bored listening to the nonsense they talk when they’re off their heads.’

‘Jules can be very funny.’

‘For half an hour, and then they both become boorish and repetitive and vicious.’

‘What do I become?’

‘Never vicious, sweetheart.’

‘We could invite them for lunch on Sunday, and they won’t stay late because they’ll have work on Monday.’

‘Sunday is the one full day I have to work on the opera, and…’

I left the kitchen and hurried upstairs to clean a toilet because I had heard too many of these conversations. There was no narrative tension; the outcome was always the same.

The Gilberts were eating pasta with their three children in the kitchen-diner of their newly built red-brick house in West London the evening I met them for the first time. They asked me to join them, but I said I had already eaten. Sarah Gilbert made me a coffee, using freshly ground beans, and I sat with them while they ate. She was tall and thin, with long dark hair, and would have been very beautiful if her lips had been fuller and her nose a little shorter. Her husband, Harry, was losing his hair and looked like he ate pasta too often, but it was the face of someone you’d be happy to find yourself sitting next to at a wedding.

‘I’m a manager at an airline, so I’m out of the country a lot, and it isn’t fair to expect Harry to do the cleaning as well as everything else when I’m away.’ She looked at her husband, who smiled at her.

I liked that they felt they had to justify having a cleaner – they didn’t take their privilege for granted.

‘I work from home, so I’m here when the kids get back from school,’ he said.

‘Is there any chance you could come twice a week? It would stop things mounting up,’ she said. ‘These monsters do create quite a mess.’

The monsters smiled proudly at me.

‘Yes, I think I could manage that; one of my clients is leaving the country in two weeks.’

‘I might occasionally have to go out for an hour and leave you alone with the kids – they’ll be doing their homework,’ said Harry.

‘That’s fine. You can give me a mobile number in case there’s a problem.’

‘That would be great.’

‘Gerry, could you try to eat your spaghetti without decorating the room with it? Twist a few strands around your fork like I showed you.’

Gerry looked about eight years old.

‘You’ll never keep a girlfriend if you cover her in spaghetti when you go on a date,’ said Nick, who was around six years older than his brother.

‘Nick is going steady,’ said his mother, raising her eyebrows. ‘He has dates in McDonald’s.’

‘Maybe Gerry will have a boyfriend,’ said Florence, his sister. She was the eldest.

Gerry looked as if he was going to cry.

‘It would be lovely if you had a boyfriend, Gerry,’ said his mother. ‘Girlfriend, boyfriend; it won’t matter to us.’

‘Gerry might be a girl when he grows up. We have three boys transitioning in our school,’ said Nick.

Gerry looked confused. ‘What’s transitioning?’

‘Nothing you need to know about yet, darling,’ said his mother. She turned to the other two. ‘For God’s sake, stop teasing him.’

‘Ms Chapman said it’s important we have open and frank discussions about sexuality and gender. It’s good for our mental health,’ said Nick.

‘And your father and I agree with Ms Chapman, but do we have to have these discussions when we have a guest?’ She turned to me. ‘They’re putting on this performance for you.’

‘It’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’m enjoying it.’

She smiled at her husband to let him know that she would trust me with their children.

I looked forward to my days at the Gilberts’ – I liked the noise and the energy of family life. Gerry followed me around the house, telling me about his video games; I think he missed his mother, and he wasn’t allowed to interrupt his father when he was working. Nick sometimes asked me to put mousse in his hair, and to help him style it before he went on dates. Florence played me tracks by her favourite group, and showed me photos of the band members.

The children were at school one morning when Harry came into the bathroom I was cleaning and asked if I’d like a coffee. I had woken late that morning and rushed out without breakfast, so I accepted his offer. When he came back with two cups, he said, ‘Have a break. Join me in the kitchen.’

I must have looked dubious: I’d had experience with neglected husbands.

‘I haven’t had a conversation with an adult for four days, and I’m beginning to talk like, you know, a teenager. And it ain’t cool, man.’

I laughed. ‘Well, it would be good to have a break.’

We sat opposite each other at the ceramic kitchen table and he passed me a packet of shortbread.

‘The coffee is good,’ I said.

‘Life is too short for cheap wine and bad coffee. You’re great with the kids – they really like you, especially Gerry. He’d go home with you if he could.’

‘He’s a lovely boy. They’re all great.’

‘Thank you. Do you have children of your own?’

I wasn’t expecting the question, and tears started spilling down my face.

‘I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘I didn’t mean to—’

‘It’s OK,’ I said. ‘I had a miscarriage – a very late one.’

‘That’s terrible – really awful. I know how frightened we were of miscarrying when Sarah was pregnant.’

‘My husband killed himself a few months earlier; he died the night I was going to tell him I was pregnant. He was an anaesthetist, so he knew how to do it efficiently.’

‘I don’t know what to say. It’s so… sad.’

‘I didn’t know there was anything wrong. I thought we were happy.’ I looked out of the kitchen window at newly planted trees and shrubs.

‘Was he depressed?’

‘He didn’t seem to be. We both loved our jobs; he was working at the best hospital in the country and I was lecturing at the university. We had a busy social life. Nobody could believe it. I kept looking for answers, secrets he kept from me, but there weren’t any. Maybe for some people this life isn’t enough.’

‘It’s no reason to kill yourself!’

‘He must have thought it was.’

‘I shouldn’t have brought it up… it was just my clumsy attempt at small talk. I am sorry.’

‘You didn’t bring it up – it’s always there. He killed our child, too – that’s what I can’t forgive.’

‘Do you think he would have lived if he’d known you were pregnant?’

‘Probably. But staying alive for the sake of other people isn’t much of a life.’

‘No.’

‘I look at other couples and I wonder how they do it – how they succeed where we failed.’

‘There’s a lot of luck involved. If you’re very lucky, you meet someone and everything about them feels right. You don’t have to work at it. Just seeing them walk across a room is a pleasure. And you’ll do anything to keep them. As long as they’re in your life, living is… joyful. And you don’t worry about the meaning of life, or that you and everyone you love is going to die.’

‘We didn’t have that. We were good together, or I thought we were, but we didn’t have what you have.’

‘I don’t think many people do. I’ve never met anyone else I could love the way I love Sarah. I couldn’t imagine having another relationship if we split up. I remember reading a poem once that said if you think you’ve loved more than once, you’ve never loved. And I think it’s true – or it’s true for me.’

‘It takes courage to love like that.’

‘It takes courage to live without it.’

‘I suppose it does. I thought of killing myself after I lost the baby. I thought about it a lot.’

We talked for a long time before I went back to cleaning the bathroom. I felt closer to Harry Gilbert that afternoon than I’d ever felt to another human being.

I couldn’t sleep that night; our conversation was like a trapped bird flying around inside my head. The next morning I texted to say I wouldn’t be coming back. I lied about having to return to my country to nurse a sick relative. I couldn’t bear to see my story mirrored in his eyes, and to see what we never had. I knew he’d understand.

Things That Matter

Ilie in the darkness, listening to the sobbing of my cellmate. She is missing her children. A woman at the other end of the corridor is screaming; her attacker is always with her. My mind is going over and over what happened, searching for a different ending.

My limbs are accustomed to sprawling across a queen-size bed. My limbs are accustomed to being entwined with other limbs. Eight years of a narrow, stained mattress, eight years of listening to sobbing and screams. I close my eyes and see ringed plovers dancing at the water’s edge and I hear the lament of the curlew.

My mother used to read to me every night – stories where women crossed wild seas to discover new lands, climbed mountains to claim them for their queen, fought wars to win justice for the oppressed and travelled to planets where they met friendly and charming aliens who had a lot to teach humans about how to live. She made up half of them. My father turned people’s dreams into concrete and glass.

I inherited my father’s passion; I love the simple lines of beams and struts, and the beauty of mathematical equations that keep buildings standing for centuries and stop roofs blowing off in a storm.

I was in the library looking at the syllabus for my first-year engineering course when Alice sat down opposite me and said, ‘I’m looking for a fourth to play tennis tomorrow, and you look like you’ve got a good forehand.’

Something in her fine-boned face made me feel I wanted to protect her.

‘My backhand is better, and I’m left handed.’

‘Great. You’re playing with me, because my backhand is crap.’

‘It’s freshers’ week – shouldn’t we be getting drunk and taking drugs?’ I asked.

‘Drugs are for people who have no imagination.’ She took out her phone. ‘Give me your number and I’ll text you the address for the courts.’

It was one of those hot October days when the sun feels like a much-loved friend who has come back to say a final goodbye. The municipal courts in west London had grass growing through cracks in the tarmac and the net was rotting. Two boys kicked a football on the court next to us. Alice made up for her weak backhand with a serve that sent our opponents running for cover. We showed no mercy.

We drank cold lager in a pub garden with stone walls covered in blood-red leaves. We were high on the forgotten pleasure of sun on our skin and the triumph of winning.

‘Why did you think I had a good forehand when you saw me in the library?’

‘I didn’t. I thought you looked like one of Caravaggio’s beautiful boys, and I wanted to know you.’ She put her hand on mine. ‘I hope you don’t mind me saying you look like a beautiful boy.’

‘I’ve never felt the need to be a girl or a boy – I am me.’

‘Will you marry me?’

‘Your backhand isn’t good enough.’

‘I’ll work on it.’

We made love a few weeks later, and it was like the continuation of a conversation we’d been having since we met. She moved into the house I was sharing a month later. Loving her was easy – too easy. University is where you should make your mistakes, when the stakes aren’t high.

When we finished university I got a job in a big engineering company. I worked on extensions to private houses – lofts and side extensions. The houses were Victorian and there was never much room for the extensions. It was going to be years before I would be given anything interesting.

Alice got a job working for a children’s charity. We bought a flat on a street with goldfinches singing in the lime trees and cars with baby seats; our parents gave us the money for the deposit. We often spent weekends on the coast in Dorset in a holiday home owned by Alice’s parents. We’d walk for hours by the sea, watching and listening to the sea birds.

We were at a party one Saturday night and I was standing on my own when a woman with spiky blond hair, a black leather bomber jacket and a short tartan skirt came up to me.

‘You’re bored,’ she said.

I looked at the room full of women dancing and chatting. ‘It’s a good party.’

‘I didn’t mean tonight.’ Her accent was a mixture of Jamaican and East End, but I had a feeling it wasn’t her real accent.

‘You don’t know anything about me.’

Her eyes were the colour of mussel shells and she had a tattoo that looked like a Jackson Pollock painting on her neck.

‘I know you’re not one of them.’ She nodded towards the other women in the room. ‘They’re talking about property prices – you can tell by the greed in their eyes. And babies – the new lesbian accessory.’

‘Why are you here if you despise us so much?’

‘The door was open, so I came in. I never pass an open door.’

‘What do you talk about at parties?’

‘Things that matter. Give me your number and I’ll send you an invitation to an exhibition of my paintings. You might want to buy one as a present for your girlfriend.’

I gave her my number. I had once dreamed of being a painter.

‘I’m Lyssa. Go home and watch a good film. Anything is better than this shit.’ She turned and left the room.

Two weeks later, I had a text saying: ‘Exhibition tomorrow evening.’ She gave the address. I lied to Alice about having a meeting with a client. I was hoping to get her a painting as a surprise birthday present – that’s what I told myself.

Lyssa had a long room on the top floor of a warehouse in Dalston. Explosions of dark colours covered the walls. One painting looked like a volcano, another a bomb site and a third was a raging sea.

‘They’re great,’ I said. ‘Very powerful. The technique is brilliant.’

‘I hate the way women make small art, working with textiles and all that shit. They’re frightened of taking up space.’ Her black combat trousers and blue shirt were covered in paint.

I looked around the room and asked: ‘When are the other people coming?’

‘It’s a private viewing – no one else is invited.’

A charge coursed through my body.

I followed her to the living space at the far end of the room. There was a mattress on the floor, a sink and a camping stove with a double burner. We sat on old wooden garden chairs painted the colours of the rainbow.

‘How did you learn to paint so well?’

‘By painting badly for a long time. And by making it the only thing in my life that matters.’

She took a small packet from her trousers and laid out two lines of coke on a yellow plate.

‘Do you have a Jane Austen?’ she asked.

‘A first edition?’ I asked, confused.

‘A tenner,’ she said, and mimed snorting with a note.

I laughed and took one from my jeans.

After we’d had two lines each, she took my hand and pulled me on to the bed. The blue bed linen was clean and made of very fine cotton. She lay on top of me, unbuttoned my blouse and bit hard into the flesh on my shoulder. I let out a little yelp and she laughed. She moved her hands slowly over my body as if she was stretching and flattening a canvas. She stopped every few minutes and had a little bite or pressed hard on my skin.

‘I’ll do anything you want me to,’ she whispered in my ear. ‘I’ll make your filthiest dreams come true.’

When her hands had finished their journey around my body, she suddenly pushed deep inside me, again and again. I felt the rope that moored me give way.

Alice was already asleep when I got home. I’d texted to say I was having something to eat with the client. I undressed in the bathroom and saw bite marks all over my body and the beginnings of bruising. I’d have to be very careful.

She woke when I got in beside her. ‘How was it, sweetie?’

‘Boring.’

‘Poor you.’

She put her arms around me and fell back to sleep.

Betraying Alice was as easy as loving her. When friends had told me about their secret affairs, I’d never been able to understand how their partners hadn’t known.

‘Living with someone makes you an expert on how to deceive them,’ said one friend.

I heard nothing from Lyssa for weeks. I saw her everywhere, heard her voice and smelled her paint. My disappointment was shading into relief when I saw her sitting on a motorbike outside my office one evening.

‘Hop on,’ she said.

‘How did you know…?’

‘We are all prey on the savannah of the internet.’

‘Nice bike.’

‘It’s not mine.’

She drove fast down bicycle lanes, past the rush hour traffic, terrifying cyclists. She parked the motorbike on a footpath when we reached the Thames. I followed her down stone steps set into the river wall until we reached the stony sand. The sun was low in the grey metal December sky. We stood under a bridge, looking at the churning water and listening to the siren of an ambulance scream above us. A cormorant with outstretched wings stood on a high wooden post, watching us.

‘I love it here,’ she said.

She took my face in her hands and kissed me, her tongue slowly exploring my mouth. She opened my coat and moved her hand tenderly around my body while I watched the treacherous water rise.

I didn’t see her again for a month, but she was with me always – inside me. I’d forgotten to turn off my mobile one night and I got a text at about 3 a.m. with the message: ‘Private viewing tomorrow evening.’

‘Who was that, darling? There’s nothing wrong, I hope?’ said Alice. She kissed the back of my neck as I was turning the phone off.

‘Just a stupid ad.’

She was wearing a short, tight black silk dress with stilettos, and she was heavily made up. Her pupils were dilated and she was moving fast around the room.

‘I sold a painting today, for a shit load of money.’

‘Congratulations.’

‘Have you ever been fucked up the ass?’

I didn’t answer.

She laughed. ‘You haven’t – you’re a virgin! Oh, I’m going to have fun tonight.’

I got used to hiding the bites and bruises. I’d always take a shower when Alice was finished in the bathroom, and I wore a T-shirt in bed.

‘You seem different – happier,’ said Alice, after we’d eaten one evening. ‘Is work getting more interesting?’

‘Yes, it is.’ I didn’t even have to look away any more when I lied.

‘I’m glad, darling.’

I lied to the office about a site visit so that I could meet Lyssa one afternoon. When I arrived home after seeing her I had a shower, knowing Alice would be at her book club. I was stepping out of the shower when I saw the bathroom door open.