28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

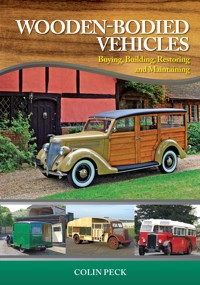

Wooden-Bodied Vehicles - Buying, Building, Restoring and Maintaining provides practical advice for anybody who is contemplating the purchase, restoration or even the building of a wooden-framed vehicle. It will guide the reader around some of the common problems and pitfalls associated with such vehicles, while at the same time highlighting some of the techniques required to end up with a beautiful wooden vehicle of which they can be justifiably proud. Combining a wide range of advice from highly skilled professional and home restorers, and the author's own experience, the book gives tips, advice and techniques concerning the ownership and restoration of a diverse range of wooden-bodied vehicles, from small cars to buses. It covers the following: How to buy - choosing the right vehicle; Dismantling a vehicle and cataloguing parts; Stripping off old varnish and sanding; Selecting the right wood; Making templates; Repairs and dealing with bugs; Bleaching and preserving; New builds and re-builds; Colouring and varnishing; Wood graining. An invaluable practical manual for anyone contemplating the purchase, restoration or even building of a wooden-framed vehicle. Gives tips, advice and techniques concerning the ownership and restoration of small cars to buses. Of interest to all woodie owners, enthusiasts and restorers. Superbly illustrated with over 450 full colour photographs showing the fantastic results that can be achieved with the right tools and techniques. Colin Peck is the founder of the Woodie Car Club and a regular contributor to road transport and classic car media.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 291

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

WOODEN-BODIED VEHICLES

Buying, Building, Restoring and Maintaining

COLIN PECK

First published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Colin Peck 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 626 0

Acknowledgements

In compiling this book I have drawn on the immense experience, ingenuity and resources of numerous vehicle bodywork restorers and builders, both professional and amateurs, from around the world: without their help this book would just not have been possible. So, it is dedicated in part to all those people who have been involved in this immense project, and also to all those future restorers and builders who may draw inspiration from reading its content.

Due to the book’s sheer size and depth it is not possible to attribute specific images to individuals, as there have been so very many. In addition I would like to offer a sincere and special vote of thanks, in no particular order, to Peter and Sandie Bayliss of Clanfield Coachbuilding (UK); Warren Kennedy and Gary Tuffnell at Classic Restorations (UK); Cumbria Classic Coaches (UK); Peter Delicata at Delicata Coachbuilders (UK); Sebastian Marshall of Historic Vehicle Restorations (UK); Steve Foreman at Forwoodies (UK); Lyle Meikle and Chris Hinks at Wicked Coatings (UK); Ron Heiden of Heiden’s Woodworking (USA); Glenn Redding of Redding Woodworks (USA); Eric Johnson at Treehouse Woods (USA); Rick Mack at Rick Mack.com (USA); Doug and Suzy Carr at Wood N’Carr (USA); Chip Kussmaul at Cincinnati Woodworks (USA); and Evan Westlake at Grain-It Technologies (USA).

I would also like to offer a vote of thanks for the personal involvement of Tim Baker, Chris Bewick, Geoff Boyd, Paul Brook, Ian Brown, Trevor Burrows, Joe Cocuzza, David Fetherston, Alan Flowers, Charles Furman, Brian Glass, Jim Grace, Frank Healey, Peter van den Heuvel, Paul James, James McIntyre, Derek McLeish, Bill Munro, Norman Reynolds, Phil Robertson, Peter Russell, Graeme Rust, Richard Smith, Bryan Smothers, Ian Strange, Mike Walker and Jeff Yeagle.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Types of Vehicle Covered

2 How to Buy – Choosing the Right Vehicle

3 Tools and Workshop Health and Safety

4 Dismantling, Cataloguing and Storing Parts

5 Stripping Off Old Varnish and Sanding

6 Selecting the Right Wood

7 Making Patterns and Templates

8 Dealing with Bugs and Making Repairs

9 Bleaching and Preserving

10 How to Build Wood-Framed Bodywork – an Introduction

11 How to Build Coachbuilt Cars

12 How to Build Shooting Brakes

13 How to Build Light Vans, Trucks and Buses

14 How to Build Newbuilds and Phantoms

15 Colouring and Varnishing

16 Woodgraining

Appendix: Sourcing Hardware

Suppliers and Resources

Index

Introduction

Wood was the material of choice for a large number of vehicle bodies from the dawn of the automobile until well into the 1950s. As a carryover from the era of the horse and cart, wood could be cut and shaped with hand tools, was relatively easy to craft into intricate shapes and – perhaps best of all – it was in plentiful supply.

The art of coachbuilding – a term derived from the horse-drawn coach era – saw wood framing used on everything from van, truck and bus bodies through to a wide variety of automobile bodies, ranging from the cheapest family sedans and open roadsters to the most expensive hand-built limousines and convertibles. In the early days of motoring most vehicle manufacturers only supplied the rolling chassis, leaving the customer to engage a coachbuilder to skilfully craft bodywork to their own specific design and requirements.

In fact, before World War II virtually all ultra-luxury vehicles were sold as chassis only. For instance, when Duesenberg introduced its Model J, it was offered as a chassis-only option for $8,500. Other examples include the Bugatti Type 57, Cadillac V-16 and all Rolls-Royces produced before World War II. Delahaye had no in-house coachworks, so all its chassis were bodied by independents, which created some of their most attractive designs on the Type 135.

Sleek metal skins were formed over hardwood frames at virtually all of the specialist marques.

Wood framing was the material of choice for vehicle bodywork until well into the 1950s.

The Austin A135 Princess was built using traditional aluminium panelling over ash framing at the Kingsbury, London, works of Vanden Plas. (Courtesy Vanden Plas Owners Club)

Austin also contracted Papworth Industries in Cambridgeshire to build 500 wooden-bodied shooting brakes in 1947 on its ‘Sixteen’ chassis.

In general, coachbuilding skills were so specialized that most chassis manufacturers procured contracts with favoured coachbuilders to build bodies for their chassis to ensure that quality standards were maintained. While most vehicle manufacturers eventually brought the coachbuilding side of the business in house, the relative ease with which wood could be cut, shaped and formed meant that wood-framing techniques enabled coachbuilders to create a number of stylish and exotic body styles that would have been difficult, if not prohibitively expensive and virtually impossible to produce in small quantities using a metal sub-structure.

Convertibles, limousines and even station wagons (US) or shooting brakes/estate cars (UK) were usually sold in small numbers, and so were often farmed out to specialized coachbuilders for their bodywork.

Coachbuilding was even more diverse at the heavier end of the market where van, truck and bus bodies were usually custom built to meet specific customer and operator requirements. While open truck bodies were often simple, if not crude in design and construction, those built for the bus and coach market often mimicked the styles and aerodynamics of some of the most stylish cars of the day. Yet underneath, they often used the same wooden structure and employed the same joints and the same construction methods as used on truck bodies.

However, while wood proved popular with coachbuilders, wood preservatives were in their infancy, and wooden bodywork often cracked under load and fell apart, rotted out, or was attacked by wood-munching bugs within a matter of years. While it was common practice for buses, trucks and luxury cars to have their bodywork replaced, often with a more modern style, after a decade or so of hard use most lightweight vans and family sedans usually ended up on the junk pile once their bodywork started to lose its structural integrity.

The Foden FE range featured one of the most stylish truck cabs ever offered on a British-built truck.

Trolleybuses began replacing tramcars in the UK from the 1930s onwards, and their sleek modern designs were constructed around a traditional wooden framework.

One of the most notable wooden-bodied vehicles of the era was the vehicle we now generically refer to as the ‘woodie’.

One of the most notable wooden-bodied vehicles of the era was the vehicle we now generically refer to as the ‘woodie’. While examples were built in many countries of the world, they were most popular in North America and the UK. The overall design and functionality was similar, but they evolved to fulfil totally different market needs.

However, their construction came to an end, almost universally, in the early 1950s as manufacturers switched to building steel-bodied wagons, which were cheaper to make and required none of the maintenance associated with wooden bodies. Also, with the increasing use of unitary bodies it was no long possible to attach structural wood framing.

Curiously, there was one woodie that was actually launched as wooden-framed coachbuilt cars were being phased out, and that was the British-built Morris Minor Traveller. Launched in 1953, it remained in production until 1971. Wood was, however, used in the framing of specialist car, van, truck and bus bodies well into the 1960s, and in some cases even in the framing of truck cabs.

The wooden-bodied station wagon was developed in the USA from an early form of taxicab, known as the ‘depot hack’.

The aim of this book is to serve as an inspiration to anybody who is contemplating the purchase, restoration or even the building of a wooden-framed vehicle, and hopefully to guide them round some of the common problems and pitfalls associated with such vehicles. At the same time it sets out to highlight some of the techniques required to end up with a wooden wonder of which they can be justifiably proud.

Unlike other books, which have focused on high levels of technical data or have drawn on the knowledge and experience gained by one individual working on a single type of vehicle, this book aims to cover as many body types and as many restoration and building techniques as possible to provide the reader with the widest possible spread of possible options and solutions.

There is no way that one single book can be the definitive guide to all coachbuilding requirements, techniques and vehicle restoration processes, but it should go some way to steering the would-be restorer down the right path. Like many things in life, there are usually multiple possible routes, options and solutions, and this is what this book aims to provide.

In researching the content of this book I found that as fast as one person would say that something could only be done one way, then along would come another individual who could prove, with a finished vehicle, that the task could be done in a completely different manner.

So in order to provide the would-be restorer or builder with the most comprehensive range of solutions, I have combined my knowledge of restoring two woodies over an eleven-year period with words of wisdom and advice from a wide range of sources. These have included some of the best known professionals and a diverse assortment of home-restorers on both sides of the Atlantic.

In completing my research I have visited a number of workshops and garages, and while the size, shape and facilities varied considerably, I found a universal passion for crafting wood that I have never found in any metal-bashing environment.

Working with wood is an art form that doesn’t come naturally to everybody, which is why this book provides builders and restorers with solutions that should match their skill and experience levels. Some may have the skill-set and enthusiasm to tackle a complete body rebuild, while others may have to farm out the work to a skilled professional in order to end up with a vehicle that meets their expected restoration standards.

So whatever your requirements, I hope that you will find this eclectic mix of views, techniques and solutions useful, and while some sections of the book may contain a number of alternative suggested fixes, I sincerely hope that you will find one that best suits your needs.

Colin Peck

Working with wood develops a passion that will be found in no other workshop or garage.

Wooden bodywork is virtually an art form in its own right, and the finished vehicle can become a thing of amazing beauty.

CHAPTER 1Types of Vehicle Covered

The art of coachbuilding encompasses a wide range of vehicle types, so I decided from the outset that as many variations as possible would be included in this book, since many of the techniques used and skills required are fundamentally the same, except perhaps in the area of size or scale. So by bringing together such a diverse range of vehicle body styles and their relative restoration processes, the reader will benefit from the experiences of the widest selection of experts ever brought together in one volume.

This chapter comprises a brief photographic description of the types of vehicle covered in these pages.

COACHBUILT CAR BODIES

The elegant and streamlined designs of the 1930s, which often mimicked developments in the aero industry, were a radical departure from the box-like vehicles of the 1920s.

AC was one of the many small car builders that used wood-framed coachbuilt bodies until the late 1950s.

This 1935 Daimler 15 with Mulliner sports saloon bodywork is typical of the 1930s coachbuilders’ art.

Just like AC, Allard also used wood framing on its sedans and sports cars

WOODIES

This category includes wooden-bodied station wagons, estate cars and shooting brakes.

The Rolls-Royce 20/25 is the epitome of the shooting-brake era of the 1920s and 1930s when such vehicles were built specifically to transport wealthy visitors to hunting lodges and game reserves.

The Ford Motor Company was one of the first car makers to bring the wooden-bodied station wagon to the masses, both in the USA and the UK.

Lancia was one of the few European automakers to offer a wooden-bodied vehicle.

Immediately following the cessation of hostilities across Europe in 1945, Britain witnessed a period of austerity, coupled with a shortage of metal and the introduction of a 30 per cent purchase tax on all new cars. Car dealers and suppliers found a loophole by constructing wooden-bodied utility vehicles that were classified as commercial vehicles and were therefore exempt from tax. This 1948 Healey was one of seventeen such vehicles bodied by Dobbs.

VANS

Many early vans were built on car chassis, such as this diminutive Austin Seven

The coachbuilders’ art could be adapted to a wide variety of body styles, such as this Morris Y-type ambulance.

The 25ft turning circle of the Austin taxicab chassis made the ideal basis for coachbuilt newspaper delivery vans in London during the 1950s.

TRUCK BODIES AND CABS

Even mass-produced trucks with steel cabs had bodywork constructed from wood right up to the 1970s.

Coachbuilt truck cabs allowed transport operators to adapt them to their operational needs, and they could be easily repaired when damaged.

The very earliest trucks had both bodywork and cabs constructed entirely from wood – some even had doors!

BUSES AND COACHES

Electric-powered trolleybuses replaced tramcars in the UK during the 1930s, and used traditional coachbuilding techniques in their construction.

Petrol- and diesel-powered buses were also constructed extensively with wooden frames during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

Wood framing allowed coachbuilders to create some truly artistic designs in low volumes that would not have been economically possible using metal framing.

NEW-BUILDS OR PHANTOMS

New-build woodies are proving extremely popular in the USA, where car builders are taking models never previously available with a wooden body and building unique vehicles.

This Canadian new-build features sheet metal from a 1950s Morris Oxford combined with woodwork in the style of a Pontiac woodie.

This woodie van was built on an Austin A40 body in Australia.

Even the Citroën 2CV could be rebuilt as a woodie.

Ford never built a Sportsman convertible on the 1939–40 models, so Eric Johnson, from Treehouse Woods in Florida, built his own.

Chrysler Corp never built a Town & Country sedan on its Plymouth range, but that didn’t stop this owner from creating one.

This little Austin Seven Special now sports wooden boat-tail bodywork.

This Railton started life as a drophead coupé, but after falling into disrepair was given a new lease of life by being re-bodied as a woodie.

CHAPTER 2How to Buy – Choosing the Right Vehicle

The purchase of any motor vehicle with a wooden body frame is not something to consider lightly. With steel bodywork on cars, vans, trucks and buses becoming mainstream during the 1940s and 1950s, there’s a strong possibility that many of today’s auto restorers will have only a limited previous experience, or none at all, of either the delights or the pitfalls of working with wood. So ‘buyer beware’!

During the fifteen years that this author has been restoring and owning woodies, I’ve seen a great many wooden- bodied vehicles that have been snapped up by eager buyers, keen to have their first experience of restoring something different – only to put the vehicle back up for sale a few months later when they realized the amount of work, time and cost involved in turning the vehicle back into anything like its original condition.

It’s far too easy to be blinded by the potential value of a restored vehicle without a full appreciation of the work involved in turning a ‘project’ vehicle into a thing of beauty and a pleasure to own and drive. I’ve always tried to remove the ‘rose-coloured glasses’ when going to view a potential purchase, but even years of experience of buying the good, the bad and the downright ugly have sometimes failed to stop me buying the proverbial ‘lemon’.

So, rather than just reflecting on my personal criteria for checking out a vehicle prior to purchase, I have sought the opinions of professional and home restorers on both sides of the Atlantic – and whilst many of their views are diverse, they certainly make a lot of sense. Here are some of their suggestions.

By carefully selecting the right project vehicle you can help to reduce the time, cost and effort it will take to build a roadworthy vehicle.

GET THE BASICS RIGHT

Suzy Carr from renowned Southern Californian woodie restorers Wood N’Carr, advises that there are a number of ‘basics’ that you need to get right when going to look at a prospective project vehicle. The first of these is to make any assessments and judgements based on viewing the actual vehicle and not just photos. This sounds like complete common sense, but it’s amazing how many people buy over the internet or from a magazine advert, and rather than travelling to view beforehand, just take a chance that the vehicle will live up to the condition that the photos appear to show.

On actually viewing the vehicle, Suzy recommends checking the structural integrity of the chassis and steel floorpan (assuming that it has one), as not only is metal very expensive to repair, but if the vehicle’s underpinnings are rusted out then there is really nothing on which to build a new wooden body.

One of the most complicated and expensive parts to repair or replace on a wooden-bodied station wagon are the main roof side headers. Covered in fabric, they are often overlooked during the initial vehicle assessment stage, but the work involved in crafting new ones can sometimes make or break a project. Suzy advises using the butt of a pocket knife to start tapping around the top where it’s covered in vinyl. ‘If you hear a hollow sound, and not solid wood, that could be a huge expense,’ she continues. ‘If you need to have new wooden headers made for, say, a 1946–48 Ford, then you are looking at around $5,000 for the pair. These are large items, which include finger joins, so check them very carefully.’

When considering the purchase of a vehicle that obviously needs major bodywork repair, you really need to ask yourself if you have the resources, the enthusiasm, and deep enough pockets to see it through to final completion.

The rarity and desirability of woodies now means that even very dilapidated vehicles are being restored.

Roof side rails are big, heavy and expensive toreplace. If tapping reveals a hollow sound then there could be internal decay.

Woodworm and bug infestations not only have an unsightly impact on the exterior surface of the wood, but they can also weaken the internal structure and joints.

This amount of woodworm damage will usually indicate a serious loss of structural integrity, and replacement of the entire section will be the only effective remedy.

These two pieces of sectioned timber show just how deep woodworm can burrow, and each hole can weaken the entire structure.

WOOD-BORING PESTS

While rot can be a headache, replacement is fairly straightforward. However, this is not the case with any form of bug infestation. Different parts of the world are home to different insects and pests, but any form of wood-boring beetle or bug can wreak havoc with wooden-bodied vehicle structures.

In the UK, woodworm is a common pest. The larval stage of a number of wood-boring beetles thrive in high humidity and poorly ventilated buildings, and while they may not attack a vehicle kept in everyday use, the same cannot be said for one that is put on blocks in a barn and locked away for years.

Peter Baylis, who runs Clanfield Coachbuilding in Oxfordshire in the UK, recommends checking the structural integrity of all joints, especially those in doors, as the residue from the animal and fish glues often used in the coachbuilding trade in the 1940s and 1950s seems a particular favourite of woodworm. This writer has actually purchased woodie doors that initially seemed rigid only to have them ‘explode’ once any pressure was put on the joints! Woodworm often bore into the joint and devour much of the tenon, leaving it with the tensile strength of honeycomb!

If left unchecked, woodworm attack can lead to serious weakening of structural timber framing and can spoil the appearance of decorative timber, giving it a pock-marked appearance where the bugs have made their escape. Whilst bug attacks on timber are often generally attributed to woodworm, there are other wood-boring pests that can also do damage; these include the common furniture beetle, death watch beetle, powder post beetle, house longhorn beetle and weevils. All of these are treated in the same way.

Spotting the Tell-Tale Signs

All these insects are beetles, and have a very complex life cycle. Eggs are laid on the surface of the wood by the adult female beetles, and these hatch out into grubs (larvae) that bore into the wood. It is these grubs (woodworm) that cause damage to the timber. The grubs eventually pupate within the wood and change into adult beetles, which emerge from the wood, mate and lay new eggs to start a new generation.

The time spent in each stage of the life cycle differs for the various insects, and in all cases the damaging grub stage is the longest. The familiar woodworm holes are caused by the adult beetles emerging from the wood.

Attack by wood-boring insects is easily distinguished from other forms of wood deterioration by the distinctive flight holes that appear both on the surface and, if examined, below the surface by the tunnels produced by the larvae.

Fine dust and powder from when woodworms have exited their bore holes is a tell-tale sign of a potential problem.

If you can slip a sharp blade into the wood then rot has surely taken hold and the section needs to be replaced.

The adult beetles of the different species can easily be distinguished, but these only live for a short period at certain specific times of the year. The larvae are most difficult to distinguish, and when there are no adults a diagnosis must rely on the nature of the destruction.

Fine wood powder and dust is often a giveaway that something has been chewing at the wood, and Suzy Carr recommends looking for termite ‘droppings’ along running boards and side mouldings, as this is a classic sign of termite infestation or post-hole beetles. She also suggests taking a small sharp knife and testing whether the blade will slip easily into suspect areas of wood. If it goes in really easily, that could mean fungus or dry rot, and if either of these conditions exists, they both just keep growing on and on, so will need to be cut out to stop the spread.

Unlike the British woodworm, whose exit holes are a sign that the ‘pest has left the building’ so to speak, termites are not that easily eradicated. So if you do buy a car that is knowingly infested, then it will need to be bagged and fogged, just like a house. Alternatively, if you have access to a large freezer of the type normally used for meat or seafood, putting the woodie into deep freeze for a while should also solve the infestation.

The decayed condition of the wood on this Morris Traveller is a clear indication of major structural problems.

A major bug infestation can reduce a woodie wagon to a pile of splinters in no time at all.

LEARN ALL YOU CAN ABOUT THE VEHICLES

Charles Furman, from the San Diego Woodie Club and chairman of Wavecrest 2011, concurs that many first-time purchasers forego the most important first steps in woodie ownership and then regret it once they realize what they have taken on.

He suggests the following basic rules to ensure that potential purchasers fully understand the vehicles, their values and culture before rushing headlong after the first one that is offered for sale.

1. What types, makes and models are available?

There’s no point in rushing in and buying the first one that comes along – do some research of model types, availability and potential values first in order to set a benchmark.

2. Which models are plentiful and which are rare?

It’s essential to know the marketplace. While the more common models may have a greater following and a good parts supply, will these virtues be reflected in lower values? On the other hand, a rare model may be highly desirable, but will you need to travel to the four corners of the globe to find parts to complete its restoration?

By benchmarking values, and the availability and desirability of the various parts, you can avoid buying a project vehicle that you will perhaps later regret.

3. Which have parts readily available, and which don’t?

So what is the main attraction of a wooden-bodied vehicle? Is it the style of the bodywork or the name of the chassis manufacturer? If it’s the latter then you need to seriously consider the availability of spare parts.

For example, a mid-1930s Ford car will have a better parts supply chain than, say, a Hudson or a Studebaker, whilst a Rolls-Royce of the same era will have better parts availability than a Hillman or a Jowett: but will the prices be astronomically expensive, and will this cost be reflected in the overall value of the finished vehicle?

Large, rare and high value coachbuilt cars may prove difficult to find spares for.

4. Some models are more popular than others – so why is that?

Some vehicles are clearly more popular than others, and an understanding of the reasons behind this phenomenon could save you much heartache further down the road. Popularity could be down to large numbers of similar vehicles being available for sale, or perhaps it’s because they are cheap and easy to restore. It could also be down to having an active club supporting owners and restorers or maybe because of excellent spares availability. But does popularity also mean that you’ll see one at every classic vehicle show from here to Timbuktu, and start to wish you had something a little more special?

No matter what the body style is, or was, and whether it’s a car, van, truck or bus, the availability of chassis parts has to be a key factor in the decision-making process.

The Morris Minor Traveller was built from 1953 to 1971, and due to the large numbers built is still one of the most numerous and popular woodies available.

5. Which best suits your intended use?

You wouldn’t buy a sports car to go off-roading or a double-decker bus when you only needed a taxicab, yet few people buy classic vehicles as a result of considering how they will be used.

If you are building a show vehicle and you’ll be the only rider, then maybe two doors and two seats would be plenty, but if there’s a need to transport friends and family, and luggage, club regalia or associated products or even pets, then maybe a few extra seats or doors might be in order.

There’s also the question of size, and whether it will fit in your garage, as well as the thorny question of engine size and performance. If you never intend to go further than a few local shows and rallies, then a slower performing motor could be all right, but if you intend to make long distance trips then you’ll need to choose a vehicle with the right mechanical specification to avoid thrashing the drive train to within an inch of its life.

Original specification engines are notoriously less powerful and thirstier than modern vehicles, so unless you are considering transplanting modern running gear, you’ll need to research drive-line options and data before you buy. While you may be happy to ‘adapt’ your requirements to the vehicle once it is finished, looking at all the possible usage requirements from the outset could make the difference between ending up with a vehicle that is just acceptable, or one that is fantastic!

Do you really need more than two seats?

A bus or coach may meet your needs in terms of passenger carrying capacity, but do you really have room to rebuild or store it?

Vintage Bentleys always sell for top prices, but the shooting brake body on this 1925 example was removed soon after it was sold at auction in the UK so that the chassis could be re-bodied as a seemingly more valuable open tourer.

6. What are the various types of woodie worth?

While this question is more specific to wooden-bodied station wagons, it could also have some bearing on other types of wooden-bodied vehicles.

The US surfing scene is intrinsically linked to the woodie culture, which has resulted in these wooden wonders eclipsing the prices of the finest equivalent sedans and convertibles. It has also seen Ford and Mercury woodies become the most desirable and therefore the most valuable.

Prices vary a great deal, so don’t go and buy the first vehicle you see for sale. It is important to benchmark condition, desired options and values via the appropriate clubs, such as the National Woodie Club (USA) and the Woodie Car Club (UK), as well as magazine classifieds and internet auctions, and then make an educated decision.

For a start, rarity does not always equate to desirability or value. For instance, a vehicle might now be considered rare because it was initially produced in low numbers because it was not particularly well received in the marketplace.

For example, in the USA a fairly rare and high quality 1948 Packard woodie might only be worth $60,000, while a fairly common 1948 Ford woodie in similar condition might be worth twice as much because Fords have a greater following and therefore demand is much higher. Truck-based woodies are also extremely rare, yet are typically less valuable than car-based versions.