Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

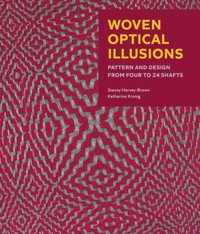

Woven Optical Illusions explores a variety of optical effects through the medium of weaving. Suitable for weavers of all experience levels, it explains the basic principles behind the illusions and shows how to create the effects in selected weave structures to give a wide range of examples and possibilities. Projects are taken from concept through weave design and development to a woven result. With over 500 illustrations, including detailed drafts and images, this fascinating book is designed to whet the appetite of anyone who is interested in optical play. Includes Clear step-by-step explanations of the complete design process and describes the science behind the optical effects and some of the history of their discoveries. It also incorporates inspirational images from other weavers working in optical effects and projects range from plain weave through to advancing twills, featuring tied weaves such as summer and winter, taqueté and beiderwand, double cloth, colour-and-weave, shadow weave, and deflected double weave.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

1Introduction

2Colour In Illusions

33D Depth Perspective

Part One – Movement

Part Two – Block building

Part Three – Weavers’ effects

4Phantom Effects

5Tilt Illusions

6Eye Jitter

7Gallery

8Technical Weaving Notes

References

Glossary of Optical Effects

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

W elcome to the wonderful world of optical illusions in weaving. If you are reading this book, it is highly probable that your attention has been caught in the past by arresting images of graphic artwork that seem to vibrate or pulse, flash or move, swell or warp. They can even have you seeing things that are not actually there! This style of art, which became known as ‘Op Art’ and ‘Pop Art’ (although notably Bridget Riley did not appreciate her art being tagged in this way as she did not want it to be seen under predominantly commercial aspects) brought these largely abstract and often monochrome geometry-driven dramatic images to a fascinated audience in the early 1960s and 1970s and they have continued to intrigue and challenge viewers since then. In fact, it is most often the paintings of artists such as Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely, M. C. Escher, Richard Allen, Jeffrey Steele and Richard Anuszkiewicz that are featured on various social media, although sadly largely unattributed. The power of these images to draw people in is magnetic.

Fig. 1.0: Nested Squares.

As weavers and designers, it was a logical step to investigate how optical illusions would translate into the woven structure. There are many examples of optical illusions and optical effects available, mostly in digital form, so a wide field was open to delve into and there is still enough material left to keep on exploring. This book was created with the intention of exploring what kinds of optical illusions can be translated into weaving and working out how best to do that. The design potential for weavers is immense, both in literal interpretations and in the development of ideas that suit the vertical, horizontal and diagonal character of weaving.

In this chapter, we lay out the basics of optical illusions, what we hope you will gain from the book, how to navigate the book and the context behind the illusions that we have chosen.

WHAT ARE OPTICAL ILLUSIONS?

An optical illusion is traditionally defined as a visual experience where what we perceive is different from what is actually present. An early example is perspective drawing. It was perfected by Renaissance artists who, greatly helped by the invention of the camera obscura, created paintings which do not seem to lie flat on the canvas. Humans take pleasure in being visually deceived – just think of magic tricks – and we often choose to try to beguile our senses with special kinds of optical stimulation. Nearly 2,500 years ago, Plato noted that ‘the same objects appear straight when looked at out of the water, and crooked when in the water; and the concave becomes convex, owing to the illusion about colours to which sight is liable. Thus every sort of confusion is revealed within us; and this is that weakness of the human mind on which the art of conjuring and of deceiving by light and shadow and other ingenious devices imposes, having an effect upon us like magic.’

As we become intellectually aware of the disparity between what we think we see and what is actually there, we become involved in the ‘seeing’ process. We most often find these visual conflicts in the field of art, but it is in science that the understanding of how these effects occur is investigated. In their most modern application optical illusions are part of Virtual Reality. There they are used to transport the viewer into a reality he/ she believes they are part of. So it is no coincidence that much scientific research has been and is still being done on our brain functions and that many researchers into these illusions are producing artworks of their own. An example for this group of artists/scientists is Akiyoshi Kitaoka, Professor of Psychology at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan. He studies visual perception and illusion and has created many wonderful images of visual illusion. His dazzling art is underpinned by serious scientific investigation. With this he stands in the tradition of the artists of the Renaissance, to name only Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo.

It is staggering to realise that the entire rainbow of light (or radiation) observable to the human eye, known as visible light, only makes up a tiny portion of the electromagnetic spectrum – about 0.0035 percent. This range of wavelengths runs from below 400 Nm (towards ultra-violet) to around 700 Nm, heading out to the infrared wavelengths.

There are about 126 million light-sensitive cells in each of our eyes. The largest proportion – 95 per cent – are rods which detect light and dark. The remaining 5 per cent are the cones, which are colour sensitive. Of these latter, there are usually three types of cone which respond to different wavelengths – 440 Nm, 530 Nm and 560 Nm. The last two longer wavelengths are associated with the ‘warmer’ colours of yellows, oranges and reds.

Everything we see is in this very narrow part of the total spectrum. How and what we see is all down to the brain and the interpretation of what the eyes see, which is heavily influenced by many factors. There are the more obvious elements of physical seeing – lenses, light levels, brightness, intensity – but also those hidden aspects which are based on more social factors which can include upbringing and education, our personal experiences and history, even our geographical location.

Anthropologically speaking, we are not the same. We don’t experience colour in the same way. There are various quotes about Nordic cultures that have many words to describe the whites of their environment as well as the myriad words for shades of green in the language of people who live in more temperate climates. There is also documented evidence that some cultures do not have a separate word for blue as Oliver Sacks documented in his book, The Island of the Colorblind. Perhaps the majority of people reading this book would find that idea quite challenging because we have so many words to describe what we see and understand as blue. And of course, anyone who is colour-blind certainly doesn’t see the world in the same way as those who have full visible spectrum sight. Colour-blindness is caused by a fault in one or more of these cone cells. Different ways of seeing are not limited to colour either. Research has shown that our understanding of perspective in art and design is heavily influenced by the rectilinear architecture that is predominant in the Western culture. Other cultures don’t necessarily share this concept.

Whilst we rely so heavily on what we see, our eyes are not to be completely trusted, and what we think we see isn’t necessarily what we actually see. Matthew Lukiesh, the Director of Applied Science at the Nela Research Labs (US) gave a definition of optical illusions in 1922:

‘In general, we do not see things exactly as they are. That is, the intellect does not always correctly interpret the deliverances of the visual sense. Sometimes the optical mechanism of the eye is directly responsible for the illusion. An illusion does not generally exist physically but it is difficult sometimes to explain the cause… Objects emit or reflect light and the eye projects images of the object on the retina. Messages are then carried to the brain where they are interpreted.’

In other words, the brain forms a perception of what’s being seen, and this perception doesn’t necessarily represent the reality.

The University of Queensland, Australia, gives a simple description of vision:

‘Our eyes and brain speak to each other in a very simple language, like a child who doesn’t know many words. Most of the time that is not a problem and our brain is able to understand what the eyes tell it.

‘The colour of an orange, the size of a chair, how far away the door is – your brain knows all these things because the eyes told it so in simple language.

‘But your brain also has to “fill in the blanks” meaning it has to make some guesses based on the simple clues from the eyes. Mostly those guesses are right (for example, I can see the door looks about this big and the light falls on it that way, so my brain is taking these simple clues and guessing the door is about one metre away).’

However sometimes the brain gets it wrong. The language can be simple, but the interpretation gets a bit mixed up. This can often be due to the paths that the information is taking through the brain – some of the routes to specific interpretation centres are somewhat convoluted, and, like the game of Chinese Whispers where a whispered message gets passed from one person to another, these brain messages get mixed up and misunderstood along the way and can end up radically different from the starting point in comprehension and/or perception. As we introduce the different categories of effect in the book, we will include scientific explanations where they are known, or what scientists think is going on.

Neuroscientist Patrick Cavanagh suggests that it is really important to understand that we are not seeing reality – we are seeing a story that is being created for us by and through our brains. In fact, our vision runs 100 milliseconds behind the real world. The more you dive into this world, the more questions you find yourself wanting to explore and this book is the result of us asking, and seeking to answer, some of those questions.

The Aim of the Book

If you are new to the world of illusions and optical effects, we hope to show you how to develop these designs into woven form and to provoke curiosity in you to delve further into this fascinating design source. Illusions are most often seen in print, digital media and painting which are all two-dimensional forms. Weaving too has a two-dimensional aspect, especially when it is seen from further away and when flat weave structures are used.

But it also possesses an inherent three-dimensionality through the interlacement of warp and weft and in that the yarns are spun and often plied, which makes fabric more than a flat plane.

Even a weft-dominant and flat weave like taqueté has a very slight textural effect, which can lead to disappointment when trying to emulate an optical effect. However, we occasionally have found that, even though not quite achieving what we hoped for, an initial idea could be further developed into an exciting fabric or art piece. And this can be the start and part of another design journey, leading out of the confines of optical illusions. On odd occasions we have included such a sample to show that the subject matter does not necessarily curtail design freedom.

In this book we are mostly focusing on eight shafts plus, but if you have four or two, do not put it down just yet! Log cabin (colour-and-weave – seeChapter 8, Technical Weaving Notes) only requires two shafts and you can play a lot with that. If you have four shafts, you can create two layers of log cabin as well as experiment with shadow weave (another colour-and-weave). You can also explore a number of Op Art ideas with double cloth or tied weaves on four shafts, optical movement involving twills and visual dimensionality with crammed-and-spaced, and colour play.

We also often try out ideas with multiple shafts and then distil the information down to fewer shafts. Wherever it is possible, we have done this so that it makes more of the ideas accessible to more weavers, whether you have a table loom, a floor loom or a dobby loom. We interchange tie-ups with liftplans. If you use a floor loom, you will probably want to re-arrange the treadles into an order that suits you. If your loom allows you to use two pedals at the same time, then you will be able to use a skeleton tie-up to give you more options. With countermarch looms, if you have a deep enough shed, this is possible if you just tie the shafts you want to raise, but you would need to check carefully that your shuttles will pass through easily, or maybe consider using low-profile shuttles.

We want to inspire and encourage you to try out the illusions and effects in other weave structures, and to develop your own effects. To empower less experienced weavers, you will find many full drafts here. But you will also find lots of profile drafts, enabling you to translate the principles into your own preferred weave structures and techniques whatever your level of weaving experience. For newer weavers, if you are not sure what a profile draft is, head to Chapter 8, Technical Weaving Notes. There you will find explanations and sample drafts of the structures we have used.

After that you will find lists of resources both online and in book form that you can mine for ideas and deeper specific technical knowledge to expand your understanding.

It may well be that you think what this might lead to, other than sampling. What are the applications of these woven illusion fabrics? We understand that not everyone is a sample queen, as we both admittedly are. However, even if one or the other woven effect ends up just being sampled, it might have added to your vocabulary of weave structures or to more familiarity with your loom or different yarns.

But be assured that there is much more. Woven optical illusions can be a talking point. We both have experienced this, when friends have looked with surprise and wonder that optical illusions can be seen outside of computers, phones, in books or art. Imagine a range of placemats arranged on a table, all woven in different colourways on the theme of twisted cord curves (seeChapter 5, Tilt Illusions), and guests can’t believe the lines they see are actually straight and parallel. That will certainly be a talking point!

Or you might wear a jacket woven with a pattern inspired by the Ehrenstein illusion (Chapter 4, Phantom Effects). Being complimented on that jacket, you could point out that the circles between the grid lines are actually ‘phantom’ shapes.

Apart from the aesthetics and the wonder of developing the weavings, this book often shows ideas on how to develop a design further, sometimes leading to a fabric that bears only a little resemblance to the original inspiration. And is it not also this that many handweavers want to create – a unique fabric of their very own making? Many classic weaving patterns have an inherent quality of optical illusion. We have presented examples of these in Part Three of Chapter 3, 3D Depth Perspective, at the same time showing how to interpret them with a more liberal approach. Chapter 6, Eye Jitter, has another example for an interpretation of the jitter effect. Here it is shadow weave, which may not be found (as yet) in any catalogue of illusions but certainly has all the hallmarks of the effect.

In Chapter 7, Gallery, you can see some extremely sophisticated examples of woven optical illusions by incredibly talented weavers, often on multi-shaft dobby looms. Many of these weavings are not yet achievable for the intermediate weaver. As with any publication, there are limits as to what can be included. The overriding aim for this book is to guide weavers with limited shaft capacity or experience towards creating optical effects. However, the experienced weaver will also find inspiration for many exciting projects. If you find yourself looking at visual effects with a new appreciation of how they work and ideas of how you might incorporate them into your own weaving, our goal will have been achieved.

Layout

Different elements of a particular type of optical effect are explored in the different chapters. There are also beautiful examples of textiles from other weavers in Chapter 7, Gallery. We are so fortunate to be connected with the world wide web of weaving and to share work from weavers internationally. These are there to showcase what has been done and is being created and to encourage you to dive in and have a go.

With a book of this nature – both inspirational and practical – it is difficult to strike the balance between keeping the flow of the text going whilst using references that the reader has to look up at the back, or by including some of the technical information in the main text. There is always a danger of over-duplicating. We have no wish to repeat information for the sake of it, but we do want to ensure that the information you want and need is in a place that you can find easily. Our solution is to include a certain amount of information in the text but if you want to do a deeper dive, you will need to refer to the Technical Weaving Notes in Chapter 8, or the other Resources as required. Whilst we are including the basic principles of the weave structures that we have used in the book so that most weavers will be able to understand and apply the principles, this is not designed to be a deep dive into specific weaving techniques and the serious student will be well served to browse publications that already exist which are dedicated to specific techniques.

In the resources at the end of the book there is an alphabetical glossary of the various optical effects we have used. We have done our best to present the information in the most understandable (if somewhat necessarily brief) interpretation possible within the context of a weaving book. If you have specialist knowledge, we apologise in advance for any errors in our understanding of the texts we have studied.

References and a bibliography of relevant research and resource material in weaving, art and science are also included.

The distinction between artist and scientist is a relatively recent historical development and you will find many of the creators of these images are physiologists, psychologists and other scientists, as well as the artists who have inspired us. Johannes Itten describes this marriage of disciplines beautifully:

‘The physicist studies the nature of the electromagnetic energy vibrations and particles involved in the phenomena of light… the physiologist investigates the various effects of light and colors on our visual apparatus – eye and brain – and their anatomical relationships and functions. The phenomenon of afterimages is another physiological topic… The psychologist is interested in problems of the influence of color radiation on our mind and spirit [including] subjective perception and discrimination of color… The artist is interested in color effects from their aesthetic aspect and needs both physiological and psychological information.’

It is difficult to find out who first uncovered various illusions, as they have been repeatedly discovered and rediscovered over the last century. And to complicate matters, new discoverers of the patterns, unaware that others precede them or else believing the uniqueness of their work, are in the habit of coining new names for the same basic phenomenon (something we know from our own field of weaving). It is even harder these days with the ubiquity of images on the internet to find out who the originator was. Where we have been able to source copyright holders of images found online, we have sought their permission and can acknowledge them and include them in the book. Where we have not found the copyright holder, we have provided details so that those images can be viewed online. (Please note that the details were correct prior to publication of this book, but may have since then been subject to change.) Whilst this is not ideal, we are lucky to be able to share the inspirations behind our explorations.

Visual illusions and effects are so much fun to explore, full of unexpected results and surprises. No matter your level of weaving experience, so long as you can calculate a warp, and put it on your loom, you will hopefully find something here to try out and get excited about!

Context

What are the illusions we are going to weave?

3D depth perspectiveRounded Shapes

This is one of the most accessible and known effects – a picture or pattern creates the impression of depth although it is drawn on the two-dimensional plane. Throughout the ages artists have used the rules of perspective drawings and while they mostly used and still use depth as a tool to depict dimension and make their work look realistic, mid-century artists (such as Riley, Escher or Vasarely) have used 3D depth in their paintings as a way to create a sensation in the viewer. It is depth itself that is explored in these artworks. Examples of the 3D depth effect come in many shapes and forms. The simplest would be blocks of ever-decreasing sizes, dazzling the eye and invoking a sense of infinity.

Fig. 1.1: Bridget Riley, Movement in Squares, 1961, creates a feeling of depth. (© BRIDGET RILEY 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRODUCED WITH KIND PERMISSION)

There are also columnar shapes. Richard Anuszkiewisz used geometry, colour and progression of lines to paint his Translumina series of seemingly impossible tubular effects. This sketch of four tubes is inspired by one of his pieces.

Victor Vasarely painted incredibly dimensional bulges, Vega-Nor to name but one. The blue, black and white bulge image was inspired by the painting. Bulges are another 3D depth effect. The Balcony print by M. C. Escher is another stunning example in which a very mundane balcony is transformed into a fantastical bulging fish-eye.

Fig. 1.2: Translumina graphic, based on Richard Anuszkiewicz’s artwork, gives the illusion of dimensional columns or threads.

Fig. 1.3: This graphic, based on Victor Vasarely’s artwork, seems to bulge out of the flat page.

Organic forms

Depth effects in fluid shapes are particularly captured in Bridget Riley’s Cataract paintings.

Fig. 1.4: Bridget Riley, Cataract 3, 1967 shows optical movement. (© BRIDGET RILEY 2022. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRODUCED WITH KIND PERMISSION.)

Block forms

Another form of the 3D effect are geometric shapes and sharp angles which evoke the sense of dimensionality – this classic example of tumbling blocks will be familiar and has been explored in art and craft. We guide you through the development of the motif in design and weaving as well as exploring variations of the theme.

Fig. 1.5: Tumbling blocks is a familiar dimensional illusion found in textiles and in decorative art.

Nested squares explore a different aspect of 3D depth which we investigate via the Vasarely Vonal-Sri painting (seeReferences).

There is a lack of stability in these concentric squares – the centre could be coming forward but could also be doing the opposite. Nested squares are also a feature in the intriguing Coffer illusion by Anthony Norcia, which includes another trick on the eye: hidden in plain sight are a number of circles.

Fig. 1.6: This nested squares graphic, based on an artwork by Victor Vasarely, either recedes down a tunnel or pops up like a pyramid.

Fig. 1.7: Anthony Norcia, Coffer illusion, reprinted with kind permission, holds many rectangles, but also hidden in plain sight are circles.

Weavers’ effects

We don’t have to leave our own field to find 3D depth perspective. Weavers’ patterns, such as basic interlacement, herringbone and plaited twills, all have a dimensional aspect. You will see in this book how their geometry can be examined and enlarged to emphasise their inherent 3D effect.

Fig. 1.8: This traditional herringbone graphic is very familiar to weavers.

Fig. 1.9: This weave motif is instantly recognisable as a possible plaited twill.

Fig. 1.10: The strong horizontal and vertical lines here give more of an interlaced feel.

Tilting lines and shapes

These illusory effects are endlessly fascinating; they play on the horizontal or vertical grid and seem to distort straight lines. Much research has been done on these illusions by neuroscientists. The twisted cord curves illusion causes straight lines to seemingly buckle. And there are other twisted cord effects, where parallel lines seem to slant towards each other.

Fig. 1.11: Twisted cord curves – straight lines that appear to bend.

Another effect is named after James Fraser, a British psychologist. His research centred on what appears to be a spiral but is really a series of concentric rings bordered by twisted cords. Although the original effect would be far too complicated to replicate on a shaft loom, we have based our work on a simpler image where twisted cords, drawn through diamonds, seem to tilt.

Fig. 1.12: Fraser diamonds have twisted cord lines that appear to be tilted.

We also look at parallel lines that seem to diverge or converge. We explore the Zöllner effect, widely researched in neuroscience.

Fig. 1.13: The Zöllner graphic illusion shows converging and diverging lines in all directions.

Here is a tilted squares illusion which was presented under the name ‘Kindergarten illusion’ in 1898. Decades later, a tiled café wall in Bristol became famous when the tilt effect of its tiled pattern was noticed and researched by neuroscientists at the local university.

Fig. 1.14: Café wall graphic with horizontal lines seemingly sliding in different directions.

Colour in illusions

Colour is used as a tool in art and design, but it can also create its own illusory effect. Again, researched extensively, there are effects named after their researchers. These show how colour can appear to be different depending on its surrounding colours.

Fig. 1.15: Bezold graphic showing impact of black and white on the same adjacent colour.

Phantom effects

Fig. 1.16: How many triangles do you see? The answer should be none but has often been between two and eight. The Kanizsa graphic shows a range of phantom shapes.

Eye jitter

Here is an illusion that tricks the eye into detaching a pattern or shape from its surroundings. Modern scientists (Ōuchi et al) have done much work on these phenomena. We explore weavable patterns and colours around this image.

These are illusions that conjure up colours or shapes out of literally nothing. The viewer’s perception gets tricked into assuming the existence of shapes or colours that are only suggested by grids or arrangements of objects. Much research has been done on these intriguing effects. They mostly carry the name of their discoverer.

Fig. 1.17: Do you see circles floating above a grid? The Ehrenstein illusion shows how interrupted grid lines give the suggestion of phantom circles.

Fig. 1.18: This Ōuchi-Spillman (adapted version) illusion has a central disc of vertical rectangles which appears to have a life of its own, moving independently from the horizontal rectangles surrounding it.

Science – How are Optical Illusions Created?

Optical illusions are nothing new – even as far back as Ptolemy (100–170 CE) visual phenomena were collated into classifications including colour, position, shape, size and movement.

Here is a very simplified definition of visual perception as the sum of three events:

1. The presence of lightLight is electromagnetic energy from the sun, transmitted to us in waves of different length. The spectrum of wavelength ranges from red (long waves) to blue (short waves). While the energy of light is expressed in its intensity and measured in lumen, brightness is our perception of this intensity and thereby relative to the viewer.

2. An image being formed on the retinaChemical changes are set in motion when light strikes the receptor cells of the retina. This process transmits information through millions of specialised cells to the brain.

3. An impulse is transmitted to the brainThe transmission of information causes changes of brain activity. These alterations are essentially what we call ‘seeing’ – a result of the analysis of the visual phenomena which we encounter.

Optical, or visual, illusions are caused by varied interactions in the brain’s visual system and cerebral cortex. There are three main types of effect – physical, physiological and cognitive. There are many visual phenomena that fit into at least two of these groups.

PHYSICAL ILLUSION

A simple example of a physical illusion is what you see when a stick half submerged in water appears to bend, which is caused by the physical appearance due to the optical properties of water.

PHYSIOLOGICAL ILLUSION

Among the topics of this book is physiological fiction. It can be an after-image, such as when you look at a light and then look away and ‘see’ a corresponding floating shape of the light in the same (positive) or complementary (negative) colour. Another example is the interaction of colours in a design or a painting.

The effect can also be seen if you gaze at a simple grid with contrasting black and white lines and then look away or close your eyes. You will see an imaginary grid in either the same distribution of light and shade as the original or its complement. Physiological illusions either arise in the eye itself or in the visual pathway, for instance where a specific receptor type in the eye has been excessively stimulated as when looking intensely at a specific colour point or area (such as a grid) and then relaxed when the eyes rest somewhere else, such as on a neutral surface – a blank page or wall – or in the middle distance.

A positive after-image, featuring the same colours as the original image, doesn’t usually last as long as a negative one (showing the complement of the original), which is why the latter are usually more noticeable. The image gradually reduces in intensity and duration depending on the colour(s) involved. This is not surprising when you think of the values of the different colours.

Another physiological phenomenon is called lateral inhibition. This is created by stark contrast, for instance, a grid of white lines on a black background. Responding to strong differences in light, contradictory signals of information occur in the brain. This leads to a lack of clarity (inhibition) in the response signals. The result is grey dots which appear at the intersections of the grid.

COGNITIVE ILLUSIONS