Xenakis – Back to the Roots E-Book

0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: transcript Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: mdwPress

- Sprache: Englisch

The electroacoustic works of the Greek-French composer Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) captivate with their radical ideas, sounds and compositional models. They were often conceived as multimedia works for specific locations and architectures. The richness of the approaches and processes gave rise to an extensive body of sources. Therefore, this volume is particularly dedicated to a philological approach, combining contributions by companions of Xenakis and renowned experts in Xenakis research with studies in philology of electroacoustic music. It concludes with a roundtable discussion of the performance of these electroacoustic works, thus linking the philological questions back to musical practice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 362

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Reinhold Friedl studied piano, composition, musicology and mathematics. He received his PhD at Goldsmiths University London and is guest professor at the Katarina Gurska Institute in Madrid. He directs the avantgarde ensemble zeitkratzer and released over a hundred CDs and LPs as a composer and performer. He received numerous prizes and fellowships as well as commissions by the French state, Berliner Festspiele, Wiener Festwochen, and BBC London, among others.

Thomas Grill works as a composer and performer of electroacoustic music, as a media artist, technologist and researcher of sound. He earned a doctorate in composition and music theory at Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Graz and researched as a Post-Doc at the Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence (OFAI) in the domain of machine listening and learning. He is currently heading the certificate program in electroacoustic and experimental music and co-heading the Artistic Research Center at Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien.

Nikolaus Urbanek is professor for musicology and currently serves as Dean of Research Studies at mdw – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. His research focuses on philosophy of music, music historiography, and theory of musical writing.

Michelle Ziegler is Deputy Director of the Seewen Museum of Music Automatons and a lecturer in Basel, Bern and Vienna. Previously, she worked as a postdoc at the chair of history of technology at ETH Zürich and the Paul Sacher Stiftung Basel. Her research areas include music of the 20th and 21st centuries, music and technology, archival practices and digital historiography.

Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Nikolaus Urbanek, Michelle Ziegler (eds.)

Xenakis – Back to the Roots

Philological Approaches to Electroacoustic Music

The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Open Access Fund of the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at https://dnb.dnb.de/

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY-NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, built upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/bync/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material.

First published in 2025 by mdwPress, Vienna and Bielefeld

© Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Nikolaus Urbanek, Michelle Ziegler (eds.)

transcript Verlag | Hermannstraße 26 | D-33602 Bielefeld | [email protected]

Cover layout: bueronardin/mdwPress

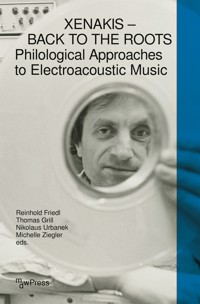

Cover illustration: Iannnis Xenakis, Indiana University, 1972. Collection Famille Xenakis DR.

Copy-editing: Johannes Fiebich

Proofread: Kimi Lum

Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar

https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839474297

Print-ISBN: 978-3-8376-7429-3 | PDF-ISBN: 978-3-8394-7429-7

EPUB-ISBN: 978-3-7328-7429-3

Contents

Introduction

Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Nikolaus Urbanek and Michelle Ziegler

Writing Electroacoustic Music

Xenakis’s Œuvre as a Theoretical Challenge

Nikolaus Urbanek

Archives, Sources, Persons and Personae in the Art of Electronic Sounds

Laura Zattra

Sketching on Paper and Tape

Creative Practices of Early Tape Music

Michelle Ziegler

Synchronising Different Temporalities

A Challenge of Writing in Musique Mixte from 1958 to 1960

Elena Minetti

Common Sonic Entities in the Electroacoustic and Orchestral Music of Iannis Xenakis

James Harley

Spatial Treatment of Sound in the Polytope de Cluny

Pierre Carré and François Delécluse

Orchestrating Noise

Traces of Mycènes alpha in Anémoessa

Marko Slavíček

Sonic Otherness. Traces of Traditional Musics in Xenakis’s Electroacoustic Œuvre

Reinhold Friedl

The Voice of the UPIC: Technology as Utterance

Peter Nelson

La légende de Xenakis

Curtis Roads

Why Did I Decide to Erase all Production Tapes of my Musique Concrète Except for the Final Compositions?

A Clarification

Michel Chion

Xenakis: Back to the Roots

A Conversation with Nikolaus Urbanek and Michelle Ziegler

Jan Brocza, Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Katharina Klement, Christian Tschinkel and Anatol Wetzer

About mdwPress

Introduction

Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Nikolaus Urbanek and Michelle Ziegler

This volume is the result of a symposium at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (mdw) in May 2022 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Iannis Xenakis. It focuses on the electroacoustic work of the Greek-French composer. Taking advantage of the possibilities at mdw, the symposium approached Xenakis’s electroacoustic works from two perspectives – through theoretical reflection on the one hand and through the performance of all of Xenakis’s electroacoustic works on the other. The performances at mdw’s Klangtheateroffered a unique opportunity to directly perceive continuities and discontinuities in his electroacoustic œuvre, giving audiences the chance to expand their experience by listening to both the composer’s aesthetic development and the technological changes taking place from the mid-1950s to the mid-1990s.

The electroacoustic work of Iannis Xenakis can be differentiated into individual phases, each of which is related to different aesthetic, technical and historical contexts.1 An early first phase in the late 1950s and early 1960s is marked by his experiences in Le Corbusier’s architectural studio, his contact with Pierre Schaeffer and his work at GRMC (Groupe de recherches de musique concrète). Inspired by musique concrète, Xenakis used pre-recorded acoustic material in his electroacoustic works, which could range from crackling and hissing like burning charcoal to noises sounding like jet engines or the processed recordings of bells. This phase comprises the following tape works: Diamorphoses (1957), Concret PH (1958) for the Philips Pavilion of the Brussels World’s Fair, Analogique B (1959), Orient-Occident (1960) and finally the scandalous Bohor (1962) – the two withdrawn film soundtracks Vasarely(1960) and Formes rouges (1961) should also be mentioned in this context. The second phase is marked by the composition of the first ‘polytope’, Polytope de Montréal (1967) for the French Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Montréal, the ballet Kraanerg (1969) combining instrumental and tape music and the 12-channel work Hibiki Hana Ma (1970) for the World’s Fair in Osaka. The transition to what James Harley calls the third phase of large multimedia spectacles is rather smooth: Persepolis (1971), Polytope de Cluny (1972), La Légende d’Eer (1978) – the latter for the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Central to this phase of his electroacoustic composing is the inclusion of space against the background of the specific local and architectural conditions as well as the coordination of the specific multimediality of light, movement and music – which required not least the technically demanding synchronisation of sound spatialisation, lights, lasers and music. The fourth phase is marked by the development of the computer-based sound synthesis system UPIC (Unité Polyagogique Informatique de Centre d’Études de Mathématique et Automatique Musicales/CEMAMu), which allows the user to directly transform graphic structures – realised with the help of an electromagnetic pen on a large electromagnetic drawing board – into musical ones. The sonic results of this phase are Mycènes alpha (1978), the radiophonic work with texts by Françoise Xenakis Pour la paix (1981), Taurhiphanie (1987), Voyage absolu des Unari vers Andromède (1989) and the withdrawn work Erod (1997). The fifth and final phase in the early 1990s comprises only two computer-generated works: GENDY 301/GENDY 3 (1991) and S.709 (1994). Harley calls it the ‘phase of stochastic synthesis’.

This richness of different approaches as well as Xenakis’s ambition to configure his electroacoustic material on his own using sophisticated processes (multiplicative tape techniques, stochastic synthesis, granulation, to name just a few) gave rise to an extensive body of sources. This allows glimpses into his compositional process but also vividly demonstrates the experimental and at times almost contradictory ways in which he proceeded. Against this backdrop, a philological study of this heterogenous material is not only essential but also promises to be fruitful for future research of other electroacoustic musical works and source studies. The questions to be addressed are quite fundamental and include the following: In what sense can electroacoustic recordings be regarded as text? What do words like “original” and “authenticity” mean, and what are the consequences for electroacoustic music’s performance and interpretation? Furthermore, due to the specific material situation of the sources of electroacoustic music, basic philological research is urgently needed: tapes are increasingly falling victim to physical decay, unsystematic digitisation is obscuring musical evidence, and some machines used for the reproduction of electroacoustic music have long since been discarded and disappeared. What’s more, and not insignificantly, there exists an urgent need to preserve knowledge of how to use these machines and read the various carrying media. Against this background, a philological approach that interprets historical documents not only as textual sources but also as cultural sources could provide valuable insights.

That is why the contributions in this volume are particularly dedicated to a philological approach under the title ‘Back to the Roots’. The perspective taken by the collected contributions is twofold: On the one hand, the volume is primarily dedicated to specific philological case studies of Xenakis’s electroacoustic work and thereby contributes to Xenakis research, which has received rather little attention to date (section “Philological Practice”). On the other hand, the special characteristics of Xenakis’s compositions allow essential insights into basic philological research in the field of electroacoustic music (section “Philological Context”).

Philological Context: Based on musical-philological considerations, Nikolaus Urbanek discusses the question of how Xenakis’s electroacoustic œuvre represents a particular challenge for the development of a theory of musical writing, with a view to current approaches in transdisciplinary writing research. Laura Zattra reflects on the personal archives of different composers of electroacoustic music as a whole body of sources and a mirror of the collector’s personality, incorporating mixed methods of philology, archaeology, oral history and ethnography. In the case of early tape music, Michelle Ziegler argues that a comprehensive evaluation of compositional practices needs to consider sketches on paper in connection with sketches on tape, as they both reveal integral parts of the creative process. Elena Minetti explores the writing strategies of different composers to achieve a specific function in musique mixte: the synchronisation of musical events between recorded sounds and live instruments or voices.

Philological Practice – Xenakis’s Challenge: As a vantage point for the subsequent philological studies of Iannis Xenakis’s works, James Harley anchors the electroacoustic music of the composer in his orchestral œuvre by demonstrating common sonic entities in both. Two case studies then evaluate expansive archival sources: Pierre Carré/François Delécluse demonstrate that the recent discovery of a digital command tape for the Polytope de Cluny not only allowed different re-enactments of the multimedia show in 2022, but in combination with an examination of other archival documentation gives an insight into Xenakis’s thinking on sound and space. Based on a close study of the sources for the electronic piece Mycènes alpha and the instrumental pieceAnémoessa (1979) for choir and orchestra, Marko Slavíček argues that for Xenakis self-borrowing was a means of exploring instances of sonic material in diverse contexts, relying on drawing as a compositional tool. Reinhold Friedl digs for hidden sources and shows that Xenakis was not only inspired by traditional musics but also borrowed their sounds extensively in his electroacoustic work. Peter Nelson breaks with the notion of the legendary intransigence of Xenakis’s computer instrument UPIC by reimagining it as the re-intonation of ancient voices, thereby envisioning “technology as utterance”.

Back to the Roots: The third and final section of the book reveals the liveliness of an encounter with Xenakis’s person and music with the accounts of two of Xenakis’s companions and with a round table on the performance practice of his electroacoustic works. Curtis Roads describes how his encounters with Xenakis provided a clear direction for starting his own composition algorithms and in general fostered an understanding of composing as a contribution to humanity. Michel Chionexplains the decision to dispose of the production tapes for his musique concrète from a composer’s perspective in order to avoid the undocumented publication of single elements and to prevent the work from being misunderstood as a “succession of pretty sounds” that might be abused as such in other music. In the concluding roundtable, Jan Brozca, Reinhold Friedl, ThomasGrill, Katharina Klement, Christian Tschinkel and Anatol Wetzer give insight into their decisions in the preparation of the performances in 2022 and thereby reveal the variety and vitality of approaches that consider the roots of the past and result in a lively actualisation of Xenakis’s electroacoustic work.

The editors are deeply indebted to Max Bergmann and the mdwPress Board of Trustees for including this volume in the mdwPress publishing programme. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose peer reviews provided important information. Many thanks also go to Kimi Lum for her fantastic foreign language editing and to Johannes Fiebich for his help in finalising the manuscript. Last but not least, many thanks to the authors for their wonderful co-operation.

Basel – Berlin – Vienna, summer 2024

Reinhold Friedl, Thomas Grill, Nikolaus Urbanek and Michelle Ziegler

1The years of composition given in this book are based on the Xenakis catalog of works by Durand-Salabert-Eschig (https://www.durand-salabert-eschig.com/en-GB/Composers/X/Xenakis-Iannis.aspx) and the website of “Les amies de Xenakis” (https://www.iannis-xenakis.org/en/category/works/). In cases of doubt, the information follows the premiere dates and not the composition dates, as in the case of La Légende d’Eer, for example.

Writing Electroacoustic Music

Xenakis’s Œuvre as a Theoretical Challenge

Nikolaus Urbanek

Even though the catalogue of electroacoustic works represents only a small part of Xenakis’s extensive œuvre, it is nonetheless a very central group of works, to which eminent music-historical significance must be attributed in various respects.1 As he was not bound by instrumental limitations and traditional performance conventions, Xenakis had the opportunity to develop creative ideas and musical concepts with great radicalism. Not least against this background, the discussion of Xenakis’s electroacoustic works remains an extremely productive challenge in several respects. On the one hand, the electroacoustic works of Xenakis reflect in their chronological progression central situations of a history of electroacoustic music that essentially also refers to developments in the field of (studio) technology. On the other hand, the musical, medial and material heterogeneity – ranging from tape compositions with the inclusion of pre-existing acoustic and musical material, to works of ‘musique mixte’ (a combination of tape music with instrumental music), to the great multimedia ‘ spectacles’ that allow space, light and music to interact, to graphically conceived computer music – leads to considerable differences in the given compositional practices – to which the surviving sources, at least, bear eloquent witness.

Back to the Roots?Towards a Philology of Electroacoustic Music

But what do we actually hear when listening to the electroacoustic music of Iannis Xenakis? This challenging question marks the starting point of Reinhold Friedl’s dissertation Towards a Philology of Electroacoustic Music – Xenakis’s Tape Music as Paradigm (cf. Friedl 2019). It is not meant to be a rhetorical question but deals, rather, with a remarkably delicate issue in a very concrete sense: As Friedl has extensively shown, commercially available versions of some works and even official performance versions contain major faults. These faults include the use of incorrect sample rates in the transfer of individual versions, fundamental errors in digitisation (for example, the performance version of La Légende d’Eer was digitised backwards) or the absence of individual tracks or entire passages, etc. (cf. Friedl 2012, 2015, 2019). Friedl develops his diagnosis starting from the obvious irritation of basic observations (e.g., different lengths of different versions) and continues this in the analysis and comparison of diverse sources such as master tapes, official rental material for performance as well as commercially available versions on CD. Finally, the reflections gained from the acoustic sources are discussed on the basis of further workshop materials (sketches, notes on technical conditions, scores, but also letters and ego documents among others), so that Friedl plausibly explains the process of creation of selected works on the basis of the workshop materials and in locating the individual (textual) sources stemmatologically within this. On the basis of his comprehensive research, Friedl succeeds in making clear how profitable it can be to go back to the sources when researching electroacoustic music; this is indispensable in order to be able to secure the foundations, to develop an understanding that there may be not only one original but multiple manifestations of a single work, to identify and eliminate existing errors – ultimately with a view to publishing a critical edition of the works.2

But when do we know that something is an error at all? Symptomatic in this context is Gérard Pape’s response to Friedl’s error diagnoses with regard to the transferring of La Légende d’Eer:

Why does Friedl call it a ‘fault’ that the test tones were left in? (Here I mean in the new master tape that Salabert has published, not in the Mode recording, which does not include these tones.) If they were included on the master tape, Xenakis must have put them there for a reason. In any case, it was quite typical to include such tones for performance reasons at the time (1970s). Anyone that knows Xenakis’ music, even a little, wouldn’t make the mistake to think the test tones are part of his music. (Pape 2015: 123)

Regardless of how the question regarding the error is ultimately to be decided, the strategy of Pape’s argumentation is of considerable interest at this point: It makes clear that the diagnosis of what can be regarded as an error at all can only be made plausible on the basis of intensive philological research, which also refers to theoretical, historical, aesthetic and compositional contexts. Pape’s argumentation is by no means based exclusively on source findings, but also on the intentions (of the composer or the publisher) and the customary practices of the respective environment at the time of the composition. This shows that the first thing to be clarified is whether a certain moment that is assumed to be defective is to be evaluated in the context of “common language usage”, as a remarkable “compositional audacity” or simply as a “textual error” in need of correction (Urbanek 2013: 160f.). The answer to the question of musical error therefore does not result solely from the comparison and analysis of preserved sources3 – the recourse to the preserved sources is a necessary condition, but by no means already a sufficient one. At this point, musical philology comes into play as the scientific discipline that deals with the issue of the error in a methodologically assured manner and develops criteria for higher textual criticism, which ultimately presupposes an interpretation of the sources on the basis of the inclusion of the respective context (cf. Feder 1987; Urbanek 2013; Appel and Emans 2017).

However, it must be noted that a philology of electroacoustic music has not yet been developed to the extent that can be claimed for the general philology of music. Since fundamental questions present themselves differently with regard to electroacoustic music, this also applies to terminological issues and the relation to established musical philology. The endeavour of developing a philology of electroacoustic music can and must take its starting point in the specificity of the sources (but should go beyond that): An essential point in which a specific philology of electroacoustic music will complement the general debates of musical philology concerns the status, function and relevance of the significant sources within the creative processes. Against this backdrop Zattra elaborates

that sources, or ‘texts’ as philologists call them, have a fundamental role for the study of computer music. This type of research already shows an important background of studies, that is the textual criticism, or the philology of music. Musicological investigation of electroacoustic music should start from that and rethink philological methodologies in the light of what an electroacoustic music source could be. (Zattra 2006: 1)

In his discussion of the source situation of La Légende d’Eer, Friedl refers to the specific heterogeneity of sources that must necessarily be included in the analysis of the creative process: “Texts, graphic drafts, scores, realisation sketches from the studio, et cetera, must be taken into account just as much as material tapes, multitrack versions, stereo reductions for CD release, et cetera”4 (Friedl 2012: 33). This is what Zattra systematises in her discussion of the concept of musical sources in the field of creative processes of electroacoustic music:

Nevertheless the text within electroacoustic music is not necessarily a visible or symbolic trace. In the computer music[5] field a witness can indifferently be: 1) the audio source, that is the tape where the computation is analogically converted, or the CD, the mini disc, the memory of the computer; 2) the data storage device containing the digital data and algorithms for any process of synthesis, transformation, spatialization, automatic composition; 3) printed digital scores; 4) traditional scores in the case of mixed music; 5) different sketches by the author; 6) articles dedicated to the piece; 7) mental texts. (Zattra 2006: 2)

Considering the special status of musical sources in the field of electroacoustic music this systematisation is an important starting point. However, the effort to establish a philology of electroacoustic music cannot stop here. In her contribution to this volume, Michelle Ziegler points out a fundamental difference between sources on paper and sources on tape, which is also eminently significant for the development of a philology of electroacoustic music and has to be taken into account: Unlike notations on paper, both production and reception of sonic recordings always require a “technical mediator”. Against this background, Ziegler argues that due to the “challenges of mixed media sources in sketch studies” the philology of electroacoustic music “requires mixed methods and an expansion of traditional sketch studies” (cf. the contribution by Michelle Ziegler in this volume).

With regard to the specific situation of electroacoustic music, the mediality and materiality of the technical equipment of the studios is therefore of particular importance. The necessary inclusion of technical development, i.e., the special consideration of media history, leads to further points worth considering, as Friedl points out:

It is necessary to try to set up a genesis of the production process in respect of the media history, including the distinction between technical and musical signals, considering also text sources and oral history, and last but not least the visualization of the sound files. Also the role of the edition houses is much more important than for example in literature, because of the different legal situation, the access to the archives and the economic difference, a smaller market and a more expensive production. The media history has to be considered especially as regards the media compatibilities, technical conventions such as colours indicating the velocity a tape has to be played at, etc. (Friedl 2015: 122)

The analysis and critique of the preserved sources, which must necessarily be extended to develop a philology of electroacoustic music, raise fundamental questions that touch on far-reaching theoretical and methodological issues:

•Writing Practices: What is the specific role of the different practices of sketching, drawing, recording, electronic editing, manipulation, and programming in the creative processes of electroacoustic composing? In what sense can we speak of practices of ‘writing’ here in an emphatic sense?

•Writing Systems: What changes with the use of recording or writing systems that allow the direct fixation and manipulation of sound on tapes or other media? What are the theoretical consequences of machines (‘technical mediators’) being significantly involved in production and reproduction processes?

•Writing Spaces: To what extent does the space of composing – for example the electronic studio – play an essential role in the creative process?

•Performances: In what sense can we speak of a ‘score’, ‘script’ or ‘text’ in regard to electroacoustic works? To phrase this question slightly differently: Is there a text that is read in order to be sonically realised in a performance? What are the consequences for the performance of electroacoustic music?

Scenes of Musical Writing

The fact that ‘writing’ electroacoustic music posed a new challenge for composers in the middle of the last century is due not least to the fundamental developments in the technical and media fields, which provide new possibilities and evoke new practices of composing. Elena Minetti describes this in her dissertation Schrift als Werkzeug. Schriftbildliche Operativität in Kompositionsprozessen früher musique mixte (1949–1959) as a change in ‘scenes of musical writing’ (cf. Minetti 2023; for a theorisation of the term ‘writing scene’ cf. Campe 1991 and, regarding the field of music, more recently also Celestini and Lutz 2023). As already noted above, the changes in the writing scene of electroacoustic music touch on fundamental issues. First of all, it should be noted that the writing scene of composing electroacoustic music takes place in other spaces: The usual composer’s workshop (be it the usual study room or a ‘Komponierhäuschen’ as Gustav Mahler had during his summer vacations) is joined by the electronic studio as an important place for creative work. Usually, this studio is not situated in the realm of the private but in public spaces such as radio stations or universities. In addition, the practices of composing are also changing significantly. Not only does the use of other tools (tapes, microphones, computers) lead to collaborative forms of composing in the electronic studio, in which sound engineers, for example, can play an eminent role, but it also leads to changes in the actions and practices relevant for composing. Thus, the question arises whether one can or should speak of writing in the sense of ‘inscribing’ (in a way that sufficiently stable material traces are made by writing instruments on a writing media) with regard to the work with sound recordings. Furthermore, a fundamental change can be observed in relation to the material ‘products’ of the compositional creative process: The ‘musical text’ of electroacoustic music does not exist primarily in the form of scores written on paper but in recordings of the sound itself. This has implication for the status of the text, since the question of original and copy arises in a different way when one thinks about versions and multiple sonic formats (4-channel, 8-channel, stereo, etc.), as they were often produced for specific spaces and performances settings. All in all, fundamental questions concerning the relationship between text, recording and performance are at stake.

In numerous conversations and interviews Xenakis addresses fundamental questions of notating, writing and fixing music. Thus, he answers Bálint Andras Varga’s question as to how he arrives at melodic figures with a view to the inadequacies of traditional notation:

The drawing and thinking of the sound-image go hand in hand, the two can’t be separated. It would be silly to leave out of account, when drawing, what will sound in reality. We have also to be able to find on paper the visual equivalent of the musical idea. Any changes and modifications can then be carried out on the drawing itself. This feedback has to operate all the time. What advantage do arborescence have over traditional notation? If I use traditional notation I lose the continuity. Let us say that I have a bush of three lines that stem from the same root. If I map it in the Cartesian system of coordinates I have before my eyes the picture of what it sounds like. If I were to write the same on staves I would have to break it down into many staves and continuity would be lost. The whole thing would be much more complicated. […] While I am composing the rotation has to be quick and easy. After that we can decide on the most practical solution using traditional notation. To help planning I developed with my friends a graphic electromagnetic system at CEMAMu with which we can draw any shape and obtain the corresponding music with the help of a computer. (Varga 1996: 90)

It becomes clear that writing as the visual elaboration of musical thoughts is of considerable relevance for Xenakis, also with regard to the electroacoustic works concerning pictorial or diagrammatic aspects or the specific mediality and materiality between sound recordings and notations. Against this backdrop, it should be called to mind that the 1950s and early 1960s – the phase in which Xenakis enters the stage of music history and also composes his first electroacoustic works – were marked by fundamental debates about musical notation. They were based on the diverse developments in compositional technique and aesthetics that were of central importance in this phase of composing. This holds not only for electronic and electroacoustic music but also for the further development of serial techniques, the inclusion of chance operations, the field of instrumental theatre and (free) improvisation (cf. Borio and Danuser 1997). In addition, there were experiments with notating music in the field of so-called graphic scores (in-depth discussion of recent research into writing, for example concerning Anestis Logothetis and Roman Haubenstock-Ramati: Finke 2019, 2023 and, referring to Sylvano Bussotti: Freund 2022). The (new) notation possibilities were problematised to initiate further debates and documented as a future reference: The annual congress at the Darmstadt Summer Courses in 1964, for example, was dedicated to fundamental questions of musical notation; Earle Brown, György Ligeti, Mauricio Kagel, and Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, important protagonists of the international composer scene, gave lectures (cf. Thomas 1965; Weigel 2023: 12ff.). Haubenstock-Ramati organised an exhibition in Donaueschingen in 1959 with numerous examples of new forms of notation (cf. Zimmermann 2023), and Erhard Karkoschka and John Cage published ‘inventories’ of new forms of musical notation (Karkoschka 1966; Cage 1969). Against this background, it is not surprising that this neuralgic point in the history of musical notation has received particular attention from music-related writing research in recent years (to name a few further research contributions: Czolbe 2014; Czolbe and Magnus 2015; Grüny 2020; Magnus 2016; Schmidt 2020; Zimmermann 2009).

Towards a Theory of Writing Music6

The fundamental questions raised with regard to practices, places, and sources of writing electroacoustic music presuppose, that we take a closer look at the issue of writing music in general. Surprisingly, in the relevant musicological encyclopaedias and lexicons there is no dedicated lemma on the topic of ‘writing music’ (cf. Minetti 2023: 11). This lack of a separate, consistent theorisation in the field of musical writing is quite significant – perhaps one is so sure of the self-evident, that no further explanation is needed. We finally find what we are looking for under the term ‘notation’ – as defined in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians: Notation is

a visual analogue of musical sound, either as a record of sound heard or imagined […] Broadly speaking, there are two motivations behind the use of notation: the need for a memory aid and the need to communicate. (Bent 2001)

Even if ‘notation’ and ‘writing’ are by no means congruent terms, the reference to their functions as memory aid and communication tool addresses two essential elements that can help us in our thinking about musical writing: Music is a temporary, fleeting, ephemeral phenomenon – as soon as it is heard, it is already gone. The written fixation, on the other hand, enables the archiving, distribution and representation of the ephemeral sound phenomenon; music thus gains an independent presence in its written ‘fixation’ and ‘reification’. With the written capturing of music, cultural techniques have developed in quite different forms, enabling a switch of media from the auditory to the visual realm, thus the transformation from a transient to a permanent phenomenon. In this way, music can be saved in memory and reproduced and played back independently of its immediate context of origin. The written capturing overcomes the ephemeral nature of sound, so to speak; it is written in order to fix, to remember, to archive, to communicate, to transmit.

But is that all that must be taken into account when we discuss writing music? Let’s take a step back and try to look at the obvious: First of all, we should remember that we usually perceive written sources visually. As we can see and read music in its written state, we speak of visual objects. With regard to the ontological status of the ‘text’ of electroacoustic music, which exists for example in the form of tapes, the question of visibility would have to be extended in the direction of (machine) readability. I will return to this central problem in the course of my reflections. Secondly, it is immediately obvious that what is written is always materialised in some way, whether it is written down in pencil on sketch paper, carved in stone with a chisel or fixed within the framework of other writing systems – we therefore always and necessarily speak of material objects when we refer to writing. Beyond that, a fundamental fascination of writing music lies in the fact that not only what is already mentally present is written down, but that through writing, a space of reality that was not there before is created. Loosely formulated, we could perhaps call this process ‘composing’.

Even if we take this into account, we would have to emphatically question once again whether the lexical definition quoted above is sufficient. Is not musical writing, understood as the ‘visual analogue of musical sound’, essentially underdetermined? Do other moments play a role that cannot be considered ‘visual analogues of sound’? A change of perspective in order to expand the observation space and consider hitherto neglected aspects of musical writing is necessary.

A Change of Perspective – Towards a Broader Understanding of Writing

Writing and writtenness have always been the subject of many reflections, especially in the humanities, arts and cultural studies; as a transdisciplinary object of research, this topic is not particularly new or original. In a certain sense, this debate is also a footnote for Plato, since the discussion of writing inherits from him a formative figure of thought: the idea of the subordination of writing to the spoken word (see Plato 1922: St. 274ff.). This very idea has been authoritative in various forms over a long period of time; for example, in Ferdinand de Saussure’s fundamental reflections on linguistics in general, one can read: “Spoken and written language are two different systems of signs; the latter exists only for the purpose of representing the former”7 (de Saussure 2001: 28).

In this powerful tradition of thought, writing is first and foremost written language. As musicians and musicologists, we are by no means unfamiliar with this figure of thought; it not only underpins the definition from the New Grove Dictionary quoted above but is also decisive for the development of musical sketch research and large parts of music philology. According to a traditional understanding, musical writing is considered to be – almost parallel to the definition of writing as written language – written sound. If I were to exaggerate, I might outline the underlying model as follows: The composer has a vivid and complete idea of sound in her or his creative head and puts it down on paper in an ecstatic act of transcription without any loss or alteration. In this interpretation, the media shift from the world of compositional thought to paper is achieved without any difficulties. This perspective can be emblematically illustrated by the traditional description of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s creative process: In great contrast to the ‘titan’ Ludwig van Beethoven, who struggled to write down his works with a pencil and many sketchbooks,8 Mozart was long regarded as a pure ‘brain worker’, whose musical thoughts found their way through the pen into the immediately completely fixed score almost as if by themselves, without any effort of written drafting, sketching, checking, discarding and correcting. The fact that Mozart himself had also worked intensively on paper, as Ulrich Konrad was able to prove in a detailed study of Mozart’s sketches (Konrad 1992), was shocking news for music historiographers. The assumption that musical writing primarily represents ‘written sound’ shows not only a questionable pre-understanding of musical creative processes but also of the traditional idea of the relationship between notation and sounding interpretation: In, or better, through her or his performance, the interpreter reawakens the sound imaginations that have withered in writing to sonic life. (The strange metaphor of a ‘living interpretation’ in contrast to an ‘inanimate writing’ is all too common here and points to the precarious relationship between musical writing and performance.) To cut a long story short: In this scenario, writing is regarded as a sign for something else – musical writing is exclusively an indication of the musical sound. In this traditional interpretation, writing would then be a completely transparent medium that neutrally serves the sole purpose of archiving and communicating pre-existent sound or pre-existent ideas about sound.

In recent years and decades, there have been various changes in thinking about writing, which, for all their differences, do coincide in one aspect:9 It is increasingly being questioned whether writing should really be committed solely to representing signs for something else, or whether it might not be more adequate to think of writing as a medium in its own right (see, e.g., Grube et al. 2005). In order to do justice to the phenomenon of writing as a fundamental cultural technique in its entire breadth, we must take into account that “writings open up possibilities for action that are denied to their oral form”10 (Krämer 2011: 1). Against this theoretical background, special attention to fundamental aspects of writing-specific materiality, the focus on the discussion of the visual perceptibility of musical writing, the consideration of phenomena of performativity inscribed in musical writing systems as well as the analysis of operative moments in the act of writing itself promise particular gain. These four aspects represent constitutive and inescapable moments of musical writing and, moreover, are to be understood to a considerable extent as genuinely writing-bound aspects in which what one might call the inherent capacity of writing manifests itself in a paradigmatic way. These are aspects in which it becomes particularly clear that (musical) writing is not limited to being written language or written sound.

The proposed change of perspective does not seek to deny that different musical sign systems have been developed in the course of music history to ensure fixing, archiving and transmitting the ephemeral musical sound through notation, but points out with emphasis, that musical writing is not limited to the mere “referentiality” of a pure system of communication – musical writing is always more than written sound.

Materiality – Operativity – Iconicity – Performativity

Of course, these four aspects are not symmetrical to each other but intertwined in many ways. I would like to comment on them briefly, in some places referring to specific moments of Iannis Xenakis’s creative processes. By referencing the four aspects of materiality, operativity, performativity and iconicity, I am referring to the aforementioned theoretical approach that has been developed in the Writing Music research project in recent years (cf. Celestini et al. 2020 for further theoretical context). My point in making this reference is twofold: Firstly, the theoretical framework developed here seems to me to offer some productive considerations for approaching the situation of Xenakis’s electroacoustic composing. Secondly, the electroacoustic work of Xenakis seems to me to pose a veritable challenge to a theory of musical writing and in this sense serves as a kind of stress test for the theoretical approach.

Materiality

An indispensable prerequisite without which there can be no writing is the existence of writing materials: Materially available things with which something can be recorded in writing are always needed (for a discussion in the context of general writing research see, e.g, Greber et al. 2002). In this context we differentiate materials that are used for writing and materials upon which writing is done. Writing is bound to the writing materials used in each case: “Writing is done in accordance with the material, i.e., the material is used according to its properties – one does not chisel in paper or dip a pencil into the inkwell”11 (Celestini et al 2020: 15). Writing is dependent on a materially existing flatness, a physical surface. This results in a special spatiality of two-dimensionality, which leads to the temporally ordered succession of sonic events being transformed into a spatially ordered arrangement of written characters on a vertical and horizontal plane. This, of course, also has consequences for electroacoustic composing.

Asked what he had on the table in front of him when he started to write a score, Xenakis replied:

The notes of a scale, for instance. Or a sieve[12]. Or other notations about the synthesis with cellular automata, or pages with staves so that I can start writing, combining the various materials. […] Everything could be useful at any one time. (Varga 1996: 184, 188)

If “everything” can be of use in due course – what does this mean for the musical creative process? What is it that constitutes a source within the framework of a creative process? These first preliminary considerations already suggest that, especially regarding the electroacoustic work of Xenakis, it might be extremely worthwhile to ask to what extent and in what way the materials and tools of writing influence the writing itself, since in this context everything that serves as a tool for composers must be taken into account – therefore, we have to broaden the analytical horizon with respect to the ‘writing’ situation of electroacoustic music: the studio or the software, etc.

Operativity

The concept of ‘operativity’ was coined in the context of current debates on writing and literacy, especially by the philosopher Sybille Krämer, and in its theoretical anchoring it represents a strong argument for the necessary expansion of the understanding of writing in the direction of a non-phonographic concept of writing, because here it can be made clear that in the aspect of operativity a salient feature emerges “where writing transcends language”13 (Krämer 2005: 24): “Writings […] do not only represent something, but also open up spaces for handling, observing and exploring what is represented”14 (Krämer 2009: 104). Writing, including musical writing, serves here as a tool to produce something new; musical writing, as a tool for composing, opens up new spaces for thinking.

In the sense of a ‘diagrammatic operativity’, Xenakis refers to the importance of ‘explorative-epistemic’ writing (cf. Ratzinger 2023; Celestini et al. 2020: 24), for example, with regard to Pithoprakta:

As far as rhythms are concerned, there’s no trace of the golden section; I applied probability theory almost exclusively. I spent many months studying and experimenting in order to be able to keep all that in hand and head. I wrote down parts separately, made diagrams to find the suitable parameters of the formulas. The fact that we know a formula doesn’t on its own ensure that it will achieve our aim. We have to work keeping an eye on the end result. In other words: I had to imagine how all that would sound. And that took a long time. (Varga 1996: 75f.)

In order to clarify this fact, which remains largely unquestioned in its obviousness, from a scriptural-theoretical point of view: Musical writing serves not only the transcriptive representation of already existing sonic imaginations but also the creative production of musical sound events and (sound) phenomena. The neuralgic point of an analysis of the category of operativity within the framework of a theory of musical writing now lies in the fact that moments play a role here that have no direct “equivalent on the sound level” (Raible 1997: 29, quoted in Krämer 2003: 160) or at least on the level of sonic instantiation: What is written – as what is to be read – is available in a completely different way than sound: it can be discarded, deleted, modified, varied, improved, continued, glossed, commented on, etc. These are genuinely script-based moments in which the – ultimately also practical – potential of writings proves itself in a paradigmatic way. A spoken word, a sung sound, cannot be undone – in the realm of writing, however, there is the possibility of deleting, erasing, correcting. Ephemeral sound events, to generalise, become manageable, reflectable and manipulable in their written reification. At this neuralgic point, the study of Xenakis’s (electroacoustic) work (cf. on this issue fundamentally Xenakis 1992) provokes the question of how the theoretical framework