2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

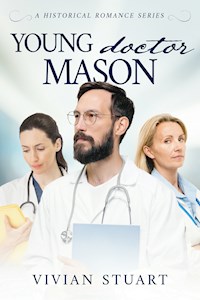

INTRIGUE. TENSION. LOVE AFFAIRS: In The Historical Romance series, a set of stand-alone novels, Vivian Stuart builds her compelling narratives around the dramatic lives of sea captains, nurses, surgeons, and members of the aristocracy. Stuart takes us back to the societies of the 20th century, drawing on her own experience of places across Australia, India, East Asia, and the Middle East. Young Doctor Mason was dedicated, sympathetic, and a very good doctor. When Kate Cluny came to assist him in his practice she knew she was going to enjoy her work, even though, in off-duty moments, Joe Mason was cool and distant to her. And then one day Barbie Ryker walked into the surgery and asked to see Joe Mason again ... Barbie Ryker who was beautiful and clever, and who had broken Joe's heart once before. Kate didn't know just how Barbie was going to win Joe back again, but she knew the lovely, scheming woman was going to try ...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Young Doctor Mason

Young Doctor Mason

© Vivian Stuart, 1970

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2022

ISBN: 978-9979-64-484-2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

CHAPTER I

‘Your coffee, Dr Mason. And there are only two more patients waiting to see you.’

The voice of his new nurse-receptionist held a note of studied and determined cheerfulness, but Joe Mason thanked her with a noticeable lack of warmth. He accepted the proffered cup, since she was holding this out to him, instead of placing it on the corner of his desk, and then, noticing that the coffee was a pale brown colour, he eyed it with distaste.

‘Well, gosh almighty? What is this? What in the world did you make it with—raw beans?’ His slow, Southern drawl expressed a wealth of scorn.

‘No, I . . . that is, I made it with boiled milk, Doctor.’ Beneath the neat white cap, the girl’s face was pink.

‘Boiled milk!’ Dr Mason exclaimed. ‘Miss Cluny, in these United States we take our coffee black or with cream. I like mine black . . . black and very strong, with plenty of sugar. Surely Miss O’Hara must have told you?’

Nurse Cluny shook her head, the embarrassed colour still glowing in her cheeks. ‘No, Doctor, I’m afraid not. But I filled the percolator, so I can easily get you another cup—it won’t take a moment. I—I’m awfully sorry.’

‘Forget it, Miss Cluny,’ the young doctor bade her irritably. He did not return his cup, continuing to study the contents as if he were inspecting a particularly nauseating laboratory specimen. ‘Don’t trouble yourself, I——’

‘It’s no trouble, Doctor,’ his new receptionist assured him. ‘That’s what I’m here for, isn’t it?’

‘Why . . .’ Joe Mason resisted the temptation to tell her acidly that he had engaged her to look after his patients, not himself.

His practice was in Harmony, once a sleepy cotton town in the State of Arkansas, which had lived up to its name, with whites and blacks co-habiting peacefully enough, so long as they were separated by the natural barriers imposed by comparative wealth and comparative poverty. Over the past twenty years or so, however, the town, under the spur of industrial development, had doubled in size and almost trebled its population. The underprivileged coloured inhabitants, who had turned —at first reluctantly—from cotton picking to find employment in coal-mines and factories or the new steel plant, were no longer poor and, in consequence, no longer content to accept either the barriers or the deprivation of their citizen rights.

There had been riots throughout the long, hot summer last year, ugly incidents, pitched battles fought between police and Negro workers and students, and outbreaks of arson and vandalism, with the inevitable bloodshed. Joe Mason, in common with the rest of the town’s doctors, had been called upon to deal with a spate of accidents and other emergencies, in addition to his day’s normal work. His office, being situated close to the University campus, where some of the fiercest battles had raged, had at times resembled a military field hospital and he had been hard put to it to cope with the demands increasingly made on his time and skill . . . most of all on his time.

Hence the need for a trained receptionist, with sufficient surgical experience to handle such emergencies when he himself was absent on his rounds or at the hospital. The summer was just beginning and there were always more outbreaks of violence when it was hot, so, Joe thought, it wasn’t too bad an idea to be prepared. The practice was scarcely large enough to carry two men or, at any rate—he smiled wryly to himself—it wasn’t prosperous enough. Too few of his patients paid their medical accounts to enable him to employ an assistant, although he could certainly have used one, for he was often run off his feet.

He glanced up to see that Miss Cluny was still waiting expectantly, her hand outheld, by his desk. He sighed and, to avoid further argument, started to drink the frothy contents of his cup. This tasted pleasanter than he had imagined it would, but in spite of the fact that his cup was empty when he set it down, he continued to feel faintly resentful—boiled milk, for crying out loud! He had known he was going to miss old Bridget O’Hara when she finally carried out her threat to retire, but until today he hadn’t realized how much he was going to dislike working with a stranger.

Bridget had been with him ever since he had taken over the practice from his father . . . and with his father before that, of course. She might have been a mite old-fashioned, he reflected, but she knew her job, she knew the patients and their case histories, as well as their addresses, and she also knew exactly how he liked things done—from the mid-morning preparation of his coffee to the listing and filing of his calls and appointments. She had been as reliable as his own right hand, as familiar to him as the room in which he worked; she had always understood his moods, sensed when he was tired and out of temper and, bless her stout old heart, while she had occasionally bullied him, she had never tried to fuss over him. Whereas this girl . . . he thrust his cup, clattering, to the far side of the desk.

Kate Cluny was young, more than usually good-looking and, Dr Mason supposed, studying her covertly, she was attractive. A combination of smoke-blue eyes, dark hair and healthily suntanned skin usually was, especially when these were set off by the impeccable neatness of a nurse’s uniform. Certainly the uniform—British, like herself—became Miss Cluny admirably, as even he was forced to concede. The demure, blue striped dress, with its white cuffs and silver-buckled belt, the starched apron and the watch pinned to her bib, might have been designed for the sole purpose of enhancing her appeal to the masculine eye. But the trouble, so far as he was concerned, Joe reflected glumly, was that, during his working hours, he did not like having his eye distracted, and he wondered again, what could have possessed Kate O’Hara to choose this girl as her successor.

He had left the choice to her. Busy with his work, absorbed in it, he hadn’t wanted to be bothered, and in any case, he had always trusted Bridget to make such decisions. for him in the past. She had engaged a substitute when she took her vacation, year after year, one of her own contemporaries, and he had had no reason to complain . . . had, in fact, hardly noticed the difference. He took his pipe from his pocket, frowning, feeling suddenly as if he needed its solace.

His new receptionist had surgical experience, Bridget O’Hara had said, and she had added, a trifle anxiously, ‘With all the trouble we’ve been having here, Doctor Joe, I figure you’re going to need someone with a cool head—and more knowledge of modern medical treatment than I’ve got—if anything of the kind starts up again on campus. Remember the last time, when they called out the National Guard and this office was right in the middle of it?’

Sure, Joe thought, he remembered all right. It had been over three hours before the ambulances had been able to get through the mob, in order to transfer casualties from his crowded office to the downtown hospital, and those three hours had been a nightmare. Bridget had done the best she knew how, but, good nurse though she was, it had been a long time since she had left training school, and as she had admitted herself, she wasn’t familiar with modern surgical techniques, was neither willing nor capable of acting on her own responsibility, even in an emergency of such magnitude. She had blamed herself for the death from haemorrhage of young Negro student, whose condition she hadn’t recognized. Which might well have been the reason why she had decided to retire and, he supposed, might also explain her choice of Miss Cluny as his office nurse. She . . .

Miss Cluny selected a record card from the box file on his desk and laid it in front of him, interrupting his thoughts and reminded him that he had no time to linger over his mid-morning break. Her glance at his as yet unlit pipe was reproachful.

‘Mrs Carelli is next, Doctor. You have her down for a home delivery in ten days’ time. There were some renal complications in the sixth month, she told me, so I checked her blood pressure while she was in the waiting room, and the specimen too. I made a note of the results for you.’

She was quick, Joe conceded grudgingly. The waiting room had been crowded, but she had still found time to talk to Mrs Carelli and to the kid with the badly gashed leg, who had come in just before she had brought him his coffee. Not that it was easy to avoid talking with Mrs Carelli, even in a crowd. She was a friendly, garrulous soul, who had been a patient of his father’s and who, having known him since he was a raw young medical student, was inclined to take advantage of the fact. Probably she had whiled away the long, tedious wait gossiping, more freely than Bridget O’Hara had ever allowed her to, with his new receptionist.

He sighed and returned his pipe to his pocket. ‘Right, then I guess I ought to see Mrs Carelli. Ask her to come in, will you?’

‘Very good, Doctor.’ Miss Cluny’s voice was pleasantly lilting, Joe’s ear registered, but he couldn’t place the accent. The only other Scots he had known had spoken with much broader accents, whereas the musical rise and fall of Kate Cluny’s voice and the pure vowel sounds were outside his ken. He knew, of course, that she had trained initially at a famous Edinburgh hospital and that she was of Scottish descent, since she had told him so, and the hospital’s reference—a particularly glowing one—had been among those she had submitted, when applying for the post as his office nurse. He found himself wondering, as she turned to leave him, why she had applied for the post and why she should have chosen Harmony, of all places, in which to work when, with her qualifications and her United States registration, she could have taken her pick of most of the big name hospitals, almost all of which were chronically short of trained nursing staff. Obviously she had chosen Harmony for some reason, since she had been acting as relief to Mrs Carmody, Head Nurse of Surgery B at the General Hospital, when old Bridget O’Hara had tracked her down and persuaded her to become his receptionist. But . . .

‘Good-a morning, Doctor! I am here once-a more, like you said.’ Mrs Carelli was breathless, heavy with the weight of her coming child—her sixth—but, as always, courageously smiling and determined to make light of her condition and the troubles that inevitably went with it, when the claims of a young family made the rest he had advised impossible for her to take.

Deftly assisted by Miss Cluny, Joe examined her, breaking into the flow of her eager chatter in order to ask a few essential questions. Mrs Carelli sought to evade them, but he persisted obstinately and learnt that, as he had feared, she had ignored his advice, wasn’t resting and had made no attempt to follow the diet he had ordered for her. He lectured her, without much hope, as she dressed behind the screens, and knew that she wasn’t listening to him, even when Miss Cluny went back to her post in the waiting room, leaving them alone together.

‘I’ll pay you a house call in a couple of days,’ he told her, making a note on his call-sheet. ‘No need for you to come to the office any more now, Mrs Carelli. You’ve simply got to try to take things easy, understand? At your age and with your blood pressure, pregnancy isn’t just the best state for you to be in.’

‘Sure, I know,’ Mrs Carelli answered resignedly, emerging from behind the screens, her fingers still busy with the buttons of her shabby brown coat and her hat, a shapeless felt, thrust defiantly on to the back of her head. ‘But I guess you know as well as I do that I can’t take things easy, Doc. Someone has-a to wash and cook and clean for the kids and my old-a man . . . well, he ain’t much of a hand at women’s work.’

‘Then tell him he’d better learn.’

‘Oh, sure, I’ll-a tell him—same as I tell him you say he’s not-a to make me pregnant!’ Reaching his desk, Mrs Carelli eyed Joe with indulgent mockery. ‘You see how much notice he takes, don’t-a you, eh?’ Her big, ungainly body shook with laughter. ‘I won’t-a repeat what he say about you. It was-a very insulting.’

‘I’ll bet it was,’ Joe acknowledged, grinning. ‘Maybe I should have a word with him myself. But seriously, Mrs Carelli’—his smile faded—‘you simply have to take care of yourself. You——’

She cut him short. ‘Say, that new nurse of yours, Doc—quite a looker, ain’t she?’

‘She is? Well, I can’t say I’ve given it much thought,’ the doctor returned untruthfully. He avoided Mrs Carelli’s bright, inquisitive eyes, conscious of embarrassment. ‘Still, it’s nice to know you approve of her.’

‘I approve very much,’ Mrs Carelli assured him enthusiastically. ‘It was-a doing me good to see someone young and-a pretty around this-a place for a change. That old Miss O’Hara, why, she was all right for your father, I guess, and she was a good-a nurse. But you are young, Doctor Joe . . . and you are getting just a mite too-a set in your ways, you got to admit it.’

‘You think so?’ Joe looked up from the prescription he was writing to stare at her, mildly surprised.

‘Why, sure I do!’ His patient’s tone was emphatic, though it wasn’t critical. ‘You know what-a they say about all-a work an’ no play, don’t you? Well, you want to start-a remembering that, Doc, else you’ll-a waste the best years of your life on folk like-a me and my old man . . . and those-a young psychos on campus who can’t-a find anything better to do than carve-a each other up and try to burn the place down.’ Mrs Carelli accepted the prescription Joe hastily finished writing up for her and smiled at him, the mockery in her dark, expressive Italian eyes succeeded, to his shocked astonishment, by something that was closely akin to pity. ‘Ain’t-a it about time you forgot what happened?’ she asked gently. ‘There are more women than one in the world, Doctor Joe, and you ought to notice a good-a looking young woman when she’s-a right under your nose, honest you ought. How old are you, huh? Thirty-four, thirty-five, maybe?’

Joe shrugged. She was a little out in her reckoning, he reflected ruefully—he wasn’t yet thirty-three. But he did not correct her, simply rose, red of face though still determinedly courteous and escorted her to the door of the waiting room.

There was some justice in her accusation, he had to admit. He worked too hard to have time for much in the way of amusement, and besides, his leisure was too restricted, too often curtailed for him to put it to the best use. In med. school, he had played football with enthusiasm and, until a couple of years ago, had taken regular weekend hunting trips to the Lake with old Ben Tracey, his father’s closest friend, but Ben’s death had put an end to that. Now, although Ben had left him the lakeside cabin in his will, Joe seldom went out there. He hadn’t lost interest, he had just been too tired, when the weekend came, to make the effort. And then, of course, there had been Barbie after that, to occupy every moment of his scant spare time . . . there had been Barbie and her son, Dave, for almost a year.

Joe hesitated by the waiting room door, as it closed behind Mrs Carelli. Miss Cluny had told him that he had one more patient to see and he knew he ought to press the buzzer by his desk, which would signify his readiness to receive whoever it was. But although he returned to his desk, he didn’t immediately press the buzzer. Instead he allowed his thoughts to drift back to Barbie, a freedom he hadn’t allowed himself for a long while. He even sought for and found the framed photograph of her that, at one time, had always stood in front of him on the desk-top. It now lay in the locked drawer in which he kept personal records and confidential case reports, and he smiled wryly to himself, as he recalled having placed it there in a fit of cold and bitter anger, the day he had read the announcement about her in the local morning papers. There was a photograph of young Dave there too, but he left that where it was, taking out only the one of Barbie.

Her face looked back at him from its frame, achingly familiar still and, he realized, still possessing the power to hurt him unbearably even now. The photograph, taken by a clever downtown photographer who had been a friend of Barbie’s, was an excellent likeness. The pose and the skilfully contrived lighting emphasized the smooth curve of her lifted chin and the delicate moulding of her cheekbones, the small firm mouth, the wide-set eyes beneath their beautifully arched dark brows, and the shapely head, with its gamine curls, held with characteristic grace and confidence.

Yet all the same, Joe decided, it was lifeless. No photograph could show Barbie Ryker as she really was. This one didn’t even hint at the infectious gaiety she had always been bubbling over with or reveal the strange, quicksilver quality about her which made her at once the most unpredictable and the most stimulating woman he had ever known. If didn’t show her as she could be either, he thought, tormenting himself with the bittersweet memory . . . tender, responsive, loving, that firm little mouth relaxed and smiling, the lips parted, the tawny eyes shining as she waited, face upraised to his, for his kiss. And it didn’t show her as she had been when they had bade each other goodbye, Joe reminded himself, with grim cynicism. He hadn’t known just how ambitious she was until then, hadn’t suspected—cotton-picking idiot that he was—that she could be cruel.

He had loved her, deeply and sincerely, and had believed that she returned his feelings in full measure. Darn it, she had certainly acted as if she did, and this had seemed to him enough— more, a million times more, than he deserved, of course—but a right and fitting basis for marriage, whenever she was ready to abandon her career and become his wife. He knew she had been married before, was aware that the marriage hadn’t been a success and that it had been on the verge of breaking up when Barbie’s husband lost his life in an airplane crash in Europe. Although he hadn’t known the husband, he had heard rumours and gathered that Vincent Ryker drank heavily and, a good deal older than Barbie, that he had virtually kidnapped her when she was little more than a High School kid, incapable of knowing her own mind. But . . . Joe laid the framed photograph down on his desk, continuing to look at it. He had liked Dave, Barbie’s small son, liked and pitied him and, in all honesty, had looked forward to becoming the boy’s stepfather and making a home for him, where he would feel secure and wanted, for his own sake as well as for hers.

Joe’s mouth tightened involuntarily. He had been every kind of a stupid, conceited fool, no doubt of that, he told himself. For God’s sake, he had never looked any further, never questioned his luck and certainly hadn’t suspected, during the year he had known her, that Barbie might regard him as a temporary expedient, a useful and devoted escort, who would do until somebody better came along. Or—he smothered a sigh. Or until the chance was offered for her to escape from the uninspiring drudgery of the reporters’ room of the Harmony Herald to the glamour and the limitless opportunities which went with the job of fashion columnist on a New York newspaper. He didn’t blame her for taking the chance when it came. In her place, he had to concede, he would have found it hard to resist and, the Lord knew, Barbie had worked hard and waited long enough to have earned that chance twice over.

It was, he guessed, the manner of her going which had hurt so much . . . the finality of her goodbye, the swift ruthlessness with which she had severed the ties between them, ties that he had imagined binding and indestructible. She had offered, to his uncomprehending surprise, to leave young Dave with him, to allow the adoption of the boy to proceed as they had originally planned that it should, but because he had displayed a certain hesitation, his over-sensitive conscience bothering him, in the end she had taken her son with her and out of his life. It hadn’t been until a long while later that he had found out she had left him for another man, and then his disillusionment had been complete. He knew and he understood, but that hadn’t made it any easier to forgive, and he wondered, sitting there with Barbie’s photograph in front of him, whether this was the answer to Mrs Carelli’s accusation. Barbie hadn’t married the other guy, but . . . maybe it was.

Anyway, it seemed the most logical explanation for his mistrust of Miss Cluny and his reluctance to work with her. Joe opened the drawer and thrust the photograph back inside it, where it also covered the one of Dave. He felt suddenly ashamed of himself, as he turned the key in its lock. All good-looking young women weren’t like Barbie Ryker, of course. Kate Cluny, with her soft, lilting voice, her brisk competence and her British reserve, was probably a darned nice girl and the soul of honour . . . but he didn’t propose to find out, one way or the other. He was set in his ways, Mrs Carelli had told him and, he decided, that was how he preferred to be. He wasn’t consciously lonely or bored or unhappy—he had his work, which he liked and which kept him too occupied and too interested to be any of these things, and he had the daily human contact with his patients to satisfy his emotional needs. True, he missed young Dave Ryker, often thought about him and, still more frequently, worried about him. Yet in his more rational moments, he knew that he couldn’t have kept the little boy in what had become an austere bachelor household, run by a housekeeper and a succession of daily helps and geared entirely to his own needs, bound by his erratic time-table. Bridget O’Hara would have helped him to care for the boy and, indeed, had volunteered to do so, for she had become very attached to Barbie’s lonely little son, but when she retired, could he have asked Miss Cluny to take on the responsibility for a small boy’s upbringing, in addition to her other duties? Joe’s lips twisted into a wry grimace. If he had asked her any such thing she probably wouldn’t have accepted the post and he doubted whether anyone else would have accepted it either. There was only one Bridget O’Hara . . .

He leaned forward to press the buzzer on his desk with a suddenly impatient hand. His last patient of the morning, a husky young steelworker with a Colles’ fracture, which he had seen the previous week, was quickly dealt with and, his plaster checked, dismissed. Miss Cluny locked the street door to the office and, with a perfunctory knock, came back into his consulting room and without his asking her to, started to clear up.

Joe watched her, disguising his interest by making a pretence of sorting out his case notes and adding names to his call-sheet. She went about her work quietly and neatly and did not speak until her self-imposed task was finished. Then, glancing at him enquiringly, she said, ‘You do calls—that is, you make housevisits, don’t you, Dr Mason, until lunchtime?’

‘I make house-visits until the urgent ones are cleared up,’ Joe answered. ‘Sometimes that’s by lunchtime, sometimes it’s not. But my schedule needn’t concern you, Miss Cluny—you’re free till three o’clock. My housekeeper, Mrs Loomis, takes care of things and answers the phone. Miss O’Hara did her shopping in the lunch hour, I believe, and she had lunch in that little place across the street—the Bonnington. It’s owned by patients of mine, a Greek couple called Akilos. The food’s good and it’s quite respectable. I can recommend it, and of course it’s handy if you’re wanted for an emergency—Patty Loomis can just run across to fetch you.’

‘I see.’ Kate Cluny’s quick, amused smile was disconcerting. ‘Thank you, Doctor, but I brought sandwiches with me. I want a little time to make myself familiar with your files and so I thought, if you’ve no objection, that I’d stay in for the first week or so, until I’ve caught up with the book-keeping. I shall be in my own office, so I need not be in your way.’

Joe was to bless her for this conscientious decision, but he didn’t bless her now. The lunch hour—moveable feast though this always seemed to be—was the only chance he had, in a long day, to snatch a brief rest alone in his consulting room, jacket off, feet up and a pile of medical journals by his side. Patty, the housekeeper, knew better than to disturb him, but if this darned nurse was there, tapping away on her typewriter next door, coming in to check files and accounts, he wouldn’t get much peace. He scowled, but bit back the rather sour rejoinder that was on his lips. She was the proverbial new broom, he told himself. No doubt she would pretty soon get tired of it. His evening office hours were elastic, and as long as there were patients in the waiting room, he went on seeing them, often till nine or ten o’clock. Old Bridget O’Hara had never minded how long he went on, never reproached him save when she considered he was driving himself too hard, but this girl would find she had her work cut out to keep pace with the demands made on her and would be glad enough of the leisure he was able to allow her, once her first week was over. He snatched up his call list, thrust it into his pocket and reached for his bag . . . but Miss Cluny was before him.

‘Shall I make sure you’ve everything you need, Dr Mason?’

Joe relinquished the bag to her. He gave her a list of the drugs he habitually carried and gestured to the locked cabinet. ‘Miss O’Hara explained our system to you, I guess? Whatever is taken out of here has to be signed for and the quantity entered in the drug ledger and dated.’

‘I understand, Doctor,’ his new receptionist assured him gravely. She held out her hand. ‘May I have the key, please?’

‘You had better have Miss O’Hara’s key and keep it.’

‘Very well, Doctor.’ She took the key he gave her, stepping past him to open the cabinet. She found the drugs he had asked for, entered them in the register and then placed them carefully in his bag. The drug register in her hand, she turned her gaze uncertainly on Joe. ‘Will you sign for these, Dr Mason, or shall I?’

‘You have to, of course.’ He tried not to show his impatience. ‘Since you issued the drugs, you are responsible for any errors that may occur—I’m not. Maybe you ought to check there aren’t any.’

She did as he had suggested, signed her name and, replacing the ledger on its shelf, locked the cabinet and gave Joe his bag. ‘Will that be all, Doctor?’ Her tone was quiet and pleasant, but once again a faint tinge of colour burned in her cheeks, as if he had reproved her.

Feeling strangely guilty, Joe nodded. ‘Sure, Miss Cluny, and —ah—thanks.’ He moved towards the door, adding as an afterthought, ‘We don’t run to car radios in this neck of the woods, but Patty knows my routine, and if you should need to contact me for anything urgent, a call to the General Hospital will reach me up to about midday. I take an ante-natal clinic there two mornings a week.’

‘Very good, Doctor,’ Miss Cluny acknowledged. Joe flashed her a swift, apologetic smile and made for the door.

CHAPTER II

Kate Cluny followed her new employer to the door. Standing there, a hand on it lightly, she watched him as he crossed to where his car was parked, a tall, broad-shouldered figure in a grey suit which could have done with pressing, the worn leather bag gripped in his right hand like the badge of his calling, his fair head bare and the crew-cut hair a trifle untidy.

Why, she wondered, did he so obviously resent her? She was a stranger, in a strange place, working in unfamiliar surroundings and the routine of a general practice couldn’t be picked up in a few short hours by someone like herself, she had had no previous experience of it. Didn’t he realize that, even if she had made some mistakes, she was doing her best to please him, to learn her job and carry out her duties as efficiently and as unobtrusively as she could?

‘Why, sure you’ll like young Dr Mason,’ Head Nurse Carmody had told her with certainty, when she had first spoken of the possibility of becoming his office nurse. ‘He was a surgical resident here, you know, before his father—old Dr Luke Mason —died, and we were all very fond of him. Such a bright, lively young man . . . and he was pretty good at his job, too. I guess he could have gone a long way as a surgeon if he hadn’t had to take over his father’s practice. Dr Mason—old Dr Mason—had a coronary and he was ill for a long time, so of course young Dr Mason gave up his appointment here at the hospital and acted as locum tenens to his father. He could have come back, I suppose, when the old man died, but he didn’t, which I’ve always thought was a pity from his point of view. But, like I said, Miss Cluny, you’ll like him.’

Turning back into the now deserted waiting room, with its scattered magazines and disarranged chairs, Kate Cluny wondered whether, after all, she was going to like her new employer as much as Mrs Carmody had seemed to think she would. So far, he had struck her as touchy and unfriendly, far from the bright and amusing young houseman her colleague had so glowingly described. Probably he was tired and overworked, as so many G.P.s were, and he had neither assistant nor partner to help him, but still, even that didn’t entirely excuse his churlishness. He had hardly given her a smile all morning; he had been angry because she had forgotten he was an American and had given him white coffee instead of black, which surely wasn’t a crime? Over the drug register, he had been positively rude, biting her head off simply because she had aked him a natural and necessary question concerning one of the points Miss O’Hara hadn’t made clear.

Automatically setting the disordered room to rights, Kate stifled a sigh and sought the sanctuary of her own small domain. The receptionist’s office was a minute cubbyhole of a place, lined with green-painted metal filing cabinets and with a sliding hatch, which opened into the waiting room to enable her to take down the patients’ names and particulars as they entered. Her desk was large and it occupied most of the small amount of available space, with its heavy, old-fashioned typewriter and the telephone, set in the far right-hand side, a pad and ballpoint pen beside it for noting calls. The desk drawers contained letter and bill-heads and a variety of prescription forms, report and request cards for X-rays and hospital lab. tests, printed receipts for fees and numerous other forms and documents which, up to now, she had glanced at, but hadn’t studied.

Now was as good an opportunity as any, Kate decided, to make herself familiar with them. When she had typed the few letters and reports Dr Mason had given her and filed the cards used during this morning’s consultations, it would be time to have lunch. As she ate her sandwiches, she could investigate the various contents of the desk drawers so that, when next the doctor asked for a particular card or form, she would be able to produce it with a minimum of searching. The patients’ files would bear a careful check, too. Although in alphabetical order, it was evident that Nurse O’Hara hadn’t always returned them in that order, after use . . . but probably she knew the patients so well that, to her at any rate, this hadn’t mattered. To a newcomer, it mattered very much, and time spent now, in restoring each file to its correct place, would not be wasted. Indeed her time would have been well spent, Kate thought wryly, if only in order to convince her new employer that, whatever other failings she might have, in his eyes, she was at least reasonably intelligent and anxious to give satisfaction.

She had been working away steadily for two hours and was drinking her final cup of percolated black coffee, when Mrs Loomis tapped on the waiting room side of the hatch, to put a beaming plump face through the aperture.

‘The Doctor told me you’d be staying in till he gets back,’ the housekeeper announced. She was dressed for the street, in outdoor coat and headscarf, a tall, buxom woman in her late fifties, and she added, gesturing to the capacious net bag which hung from her arm, ‘If you’re going to be here to attend to the phone, Miss Cluny, I figured maybe you’d have no objection if I slipped out to the supermarket. I’ve groceries to get in for Dr Mason and there’s no sense in both of us stopping in to mind the phone, is there? So if you don’t mind——’

‘I don’t mind,’ Kate assured her. ‘But’—she consulted her watch—‘it’s after one o’clock and Dr Mason will have left the General Hospital, won’t he? He didn’t say where he’d be after that.’

‘He never does, Miss Cluny. But he’ll call if he’s got time, and he ought to be back pretty soon anyway. There’s a steak in the oven ready for him, if he gets back before I do. Not that he needs much looking after—he can turn his hand to most things, cooking included, so you don’t need to worry your head about anything like that.’ Mrs Loomis smiled, the smile a warning, offered in a friendly manner from one woman to another. ‘He always says he can’t stand being fussed over, and if you’ll take my advice, Miss Cluny, you’ll remember that. Get on a whole lot better with him if you do.’

‘Thank you,’ Kate acknowledged, somewhat at a loss. Had she made the mistake, she wondered, of ‘fussing over’ Dr Mason this morning? Perhaps she had. She looked into Mrs Loomis’ plump, homely face and saw that it was innocent of guile. ‘What makes you say that?’ she asked.

The housekeeper’s smile faded. ‘No partic’lar reason, Miss Cluny, except that you’re new here and I’m trying to help you. I know Dr Mason—bin coming here for over ten years now, first as a patient and then, after I lost my husband, as housekeeper, so I guess I ought to—both him and the old doctor. Young Doctor Joe . . . well, this may be telling tales out of school, but I reckon you’ll hear about it sooner or later. He went through a pretty bad time a year or two back and it’s left him kind of bitter and a mite over-cautious where women are concerned.’

‘You mean he doesn’t like women?’

‘No, not as bad as that. He’s careful, that’s all, doesn’t want to get himself involved again, see?’

‘Not quite,’ Kate confessed. A frown momentarily puckered her brow. Mrs Carmody had told her nothing of this and, aware that she ought not to encourage Dr Mason’s housekeeper to gossip about him, her curiosity was nonetheless aroused. She hesitated and then asked innocently, ‘Was he married—unhappily married, perhaps?’

‘No.’ Mrs Loomis shook her head. ‘Lucky for him it didn’t get as far as that, although it would have, if Doctor Joe had had his way. He fell for a women reporter on the Herald, a real classy young woman, with looks you couldn’t miss, but hard as nails. Barbara Ryker her name was, Mrs Ryker. She was a widow when she came here, with a small son, and I reckon she took the job on the Herald as a stop-gap, to tide her over till something better came up. Took Doctor Joe for much the same reason. I used to read her pieces . . .’ the housekeeper sighed reminiscently. ‘She was good—too good for the Harmony Herald, of course, but that idea never seemed to enter Doctor Joe’s head. He was young then and—well, I guess he was a bit of a romantic.’

It was an old story, Kate thought as, with a wealth of irrelevant detail, Mrs Loomis unfolded it, but it explained many things about Joe Mason which initially had puzzled her. She found herself feeling sorry for him, instead of being resentful because of the way he had behaved to her on that first difficult morning, at the start of her new job. From the security of her own happy love affair with Harvey Kestler—on whose account she had decided to stay on in Harmony—she could pity Dr Mason in his lonely disillusionment, pity and sympathize with him.

She and Harvey weren’t officially engaged, yet—but that would come, she knew, as soon as Harvey became a senior resident and could afford the luxury of a wife, which he had told her would be in six months’ time. Six months wasn’t long to wait, and in the meantime, they could see each other whenever he was free of his hospital duties and she of hers, and they could make plans, eager, exciting plans, for a future that held such glowing prospects for them both and . . .

‘Lord sakes, I must be on my way!’ Mrs Loomis said, bringing Kate abruptly back to earth. She hitched up her mammoth shopping bag and then hesitated, reddening a little. ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have told you all that, Miss Cluny. But like I said, I figure you’d have heard it from somebody or other sooner or later and if you know what the situation is, you’ll find Dr Joe a whole lot easier to deal with. And that old Miss O’Hara, she wouldn’t have warned you, of course—she’d just have let you dive in head first. Only . . .’ again there was a slight hesitation and then the housekeeper went on apologetically, ‘I’d appreciate it if you didn’t let Dr Mason know that I’d mentioned Mrs Ryker to you. She’s not here any more—got a job as columnist on some flash New York daily, they say—so you’re not liable to run into her or anything like that. But the doctor’s—well, a mite touchy, you understand, and he wouldn’t like it if he knew I’d gabbed about him to you.’

‘I won’t breathe a word,’ Kate promised readily, ‘about you or Mrs Ryker, don’t worry. All the same, I’m grateful that you told me because I think it will make it easier for me to work with Dr Mason, now that I—well, now I understand.’

Mrs Loomis looked relieved. ‘Thanks, Miss Cluny,’ she said, and let the hatch fall. The sound of her retreating footsteps and the faint slam of the street door, a few moments later, told Kate that she had departed on her belated shopping expedition.

The house seemed very quiet when she had gone. Kate completed her study of the account books and patients’ files and, before returning the latter to their cabinets, she restored as many as she could to their correct order. It was now two-fifteen and she decided, in Dr Mason’s continued absence, that she would make a check of the drug cupboard before he returned to his consulting room. Since she must share the responsibility for the cupboard’s contents with him, it would be as well, for her own peace of mind, to know precisely what drugs he kept in stock. Also, she supposed, as his office nurse she would be expected to replenish his stock and to make sure that he never ran short of drugs which were in daily use.

She closed her own small office and went back to the consulting room. The telephone rang just as she entered, and to her relief, when she answered it, it proved to be the hospital switchboard calling to inform her that Dr Mason would be at the hospital for the next hour.

‘He has an emergency just admitted,’ the operator explained. ‘And he asked me to tell you that he will have a meal in the canteen. If you need him, you can call here.’

Kate thanked the girl and, after removing the plate of—by this time—rather unappetising-looking steak from the oven in Mrs Loomis’ huge, high-ceilinged kitchen, she returned once more to the consulting room, unlocking the drug cupboard with the key Dr Mason had entrusted to her. The register was, as he had told her, quite simple to keep and easy to follow. Whenever the doctor required a particular drug, he or Miss O’Hara had taken it from the cupboard, noting the date and the amount taken, together with the stock still remaining . . . which made the re-ordering of supplies very easy and straightforward, she noted approvingly. In cases where a drug had been given to a specific patient, that patient’s name was, she saw, also noted, but when Dr Mason required it for his bag, for use in case of an emergency, the amount was entered against the date and described as ‘replenishment’. He carried pain-killing drugs and heart stimulants in neat plastic-cased ampules, each with its own ready sterilized hypodermic, of the kind that is discarded after one use, but there were plenty of these in the cupboard so that, beyond jotting down a note of quantity and nature from the stockist’s list, nothing more was needed.