Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Third Editions

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

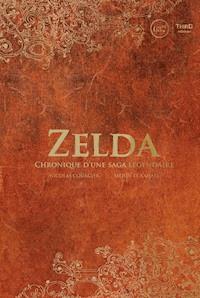

A collector's book to learn more about the world of one of the most legendary video games!

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of The Legend of Zelda, Third Editions wanted to pay respect to this legendary saga, one of the most prestigious in the gaming world. This work chronicles every game of the series, from the first episode to the latest Hyrule Warriors on 3DS, deciphering the whole universe using deep analysis and reflection. Dive into this unique publication, presented as an ancient tome, which will allow adventure fans to finally (re)discover the amazing Legend of Zelda.

Immerse yourself in this unique collection, presented in the form of an old grimoire, which will delight all adventure lovers to finally discover the fabulous legend of Zelda!

EXTRACT

In the kingdom of Hyrule, a legend has been passed down since the beginning of time: A mysterious artifact known as the Triforce, symbolized by three golden triangles arranged to form a fourth triangle, is said to possess mystical powers.

It is hardly surprising that this object has been coveted by many power-hungry men over the centuries. One day, the evil Ganon, the Prince of Darkness whose ambition is to subjugate the entire world to his will, sends his armies to attack the peaceful kingdom. He manages to capture one of the fragments of the Triforce, the triangle of power.

Daughter of the king of Hyrule, Princess Zelda is terrified at the prospect of seeing Ganon’s armies swarming over the world. She, too, seizes a fragment of the Triforce, the triangle of wisdom, and chooses to break it into eight pieces, which she then scatters across the world, hiding them to prevent Ganon from ever acquiring them. She then orders her faithful nursemaid Impa to go forth and seek a warrior brave enough to challenge Ganon.

As Impa roams the kingdom of Hyrule in the hope of finding a savior, Ganon learns of Zelda’s plans and has her locked up before sending his men to track down the nursemaid. Surrounded by these ruthless creatures, Impa is saved by a young boy named Link at the very moment when it appears that all is lost. As unbelievable as it may seem, Link has been chosen by the golden triangle of courage, and thus holds a part of the Triforce himself. Convinced that she has finally found the one who will save the kingdom, Impa hurries to tell him her story. Link accepts his mission to rescue Zelda without hesitation. Before confronting Ganon, however, he will have to gather the eight fragments of the triangle of wisdom, which are his only hope of gaining entry to the dungeon deep beneath Death Mountain where the Prince of Darkness hides. His quest has only just begun.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi - Fascinated by print media since childhood, Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi wasted no time in launching their first magazine, Console Syndrome, in 2004. After five issues with distribution limited to the Toulouse region of France, they decided to found a publishing house under the same name. One year later, their small business was acquired by another leading publisher of works about video games. In their four years in the world of publishing, Nicolas and Mehdi published more than twenty works on major video game series, and wrote several of those works themselves: Metal Gear Solid. Hideo Kojima’s Magnum Opus, Resident Evil Of Zombies and Men, and The Legend of Final Fantasy VII and IX. Since 2015, they have continued their editorial focus on analyzing major video game series at a new publishing house that they founded together: Third.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Yuna and Isia B.

Zelda. The history of a legendary saga.by Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi Published by Third Éditions 32 rue d’Alsace-Lorraine, 31000 TOULOUSE, France [email protected] www.thirdeditions.com

Follow us: @Third_Editions – Facebook.com/ThirdEditions

All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form, in whole or in part, without the written authorization of the copyright holder. Copying or reproducing this work by any means constitutes an infringement subject to the penalties stipulated in copyright protection law n°57-298 of 11 March 1957.

The Third logo is a registered trademark of Third Éditions in France and in other countries.

Edited by: Nicolas Courcier et Mehdi El Kanafi Texts by: Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi Chapter on “Link: A Character and His Evolution”: Selami Boudjerda Chapter on “Music in Zelda”: Damien Mecheri Proofreading and page layout: Thomas Savary Covers: Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi Cover assembly: Frédéric Tomé Translated from French by: Keith Sanders (ITC Traductions)

This educational work is Third Éditions’ tribute to the classic Zelda video game series. The authors present an overview of the history of the Zelda games in this one-of-a-kind volume that lays out the inspirations, the context and the content of these titles through original analysis and discussion.

The Legend of Zelda is a registered trademark of Nintendo. All rights reserved.

English edition copyright 2017 Third Éditions. All rights reserved.

ISBN 979-10-94723-59-3

This book is dedicated to Justin Carroz, to his family,to his friends and everyone who loves the legend.Remember, the world can always use another hero.May the Triforce guide you on all your adventures.Never stop working for a better future.

PREFACE

In February 2016, the Zelda saga celebrated its thirtieth anniversary. More than a quarter-century later, Nintendo’s hit series is still very much a standard-bearer for the brand, alongside its iconic Mario series. Created by Shigeru Miyamoto in 1986, the saga is still viewed by players with a certain reverence. Each individual title has a strong reputation, and the series as a whole enjoys a level of prestige that is rarely called into question. With installments available on all of Nintendo’s different platforms, this flagship franchise has also served as a showcase for the Kyoto-based developer’s technical and design prowess.

The first episode of Zelda made a powerful impression upon its release, introducing a new approach to the action-adventure genre. One Zelda installment followed another in sure-footed succession, displaying an impressively consistent level of quality that few other series have been able to match. Although the franchise has appeared in many incarnations in a variety of media (manga, animated series, merchandise), it has above all been a source of inspiration to other games that have taken it as a model. Those titles, ranging from Ōkami and Darksiders to Alundra and 3D Dot Game Heroes, all of them heirs to the original ideas first set forth by Miyamoto, have helped to popularize and build upon the Japanese designer’s vision for video games.

What is it that defines the Zelda series more than anything else? We might start by mentioning the world in which it takes place, Hyrule, along with its three main characters: Link, Princess Zelda and the evil Ganon. We might also mention the Triforce, the magical artifact that everyone covets. However, as part of the more rigorous and analytical approach that we intend to take here, we will instead focus on its gameplay system, quite innovative for 1986, which ties the hero’s development of new skills to exploration and the acquisition of precious new objects. To complete his quest, Link has to visit villages, explore dungeons, and battle tough bosses, all within a well-defined framework that is re-used in one episode after another.

We can also quite reasonably argue that the essence of Zelda lies first and foremost in Nintendo’s skill in game design. In these games, the developer has chosen to express its own vision of what an adventure game should be: a seamless blend of action, adventure and role-playing (stripped of the genre’s unwieldier aspects), yielding a gameplay experience that is not only simple, but deeply intuitive. This original structure reflects a certain philosophy towards video games, manifested on screen in the character of Link—so very appealing, and yet so very silent.

Just as in the Mario and Donkey Kong games, players find themselves on familiar ground from the very first moments of a Zelda game. In fact, this sense of familiarity goes well beyond visual impressions. It’s something you experience with the controller in your hands, through a control scheme that instantly feels natural and immediate. Anyone returning to the world of Zelda has the chance to re-experience the unique science of its gameplay, in which the individual elements (story, level design, difficulty) are masterfully combined in service of a single goal: player enjoyment.

Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi

Fascinated by print media since childhood, Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi wasted no time in launching their first magazine, Console Syndrome, in 2004. After five issues with distribution limited to the Toulouse region of France, they decided to found a publishing house under the same name. One year later, their small business was acquired by another leading publisher of works about video games. In their four years in the world of publishing, Nicolas and Mehdi published more than twenty works on major video game series, and wrote several of those works themselves: Metal Gear Solid. Hideo Kojima’s Magnum Opus, Resident Evil. Of Zombies and Men, and The Legend of Final Fantasy VII and IX. Since 2015, they have continued their editorial focus on analyzing major video game series at a new publishing house that they founded together: Third.

CHAPTER I

THE LEGEND OF ZELDA

In the kingdom of Hyrule, a legend has been passed down since the beginning of time: A mysterious artifact known as the Triforce, symbolized by three golden triangles arranged to form a fourth triangle, is said to possess mystical powers.

It is hardly surprising that this object has been coveted by many power-hungry men over the centuries. One day, the evil Ganon, the Prince of Darkness whose ambition is to subjugate the entire world to his will, sends his armies to attack the peaceful kingdom. He manages to capture one of the fragments of the Triforce, the triangle of power.

Daughter of the king of Hyrule, Princess Zelda is terrified at the prospect of seeing Ganon’s armies swarming over the world. She, too, seizes a fragment of the Triforce, the triangle of wisdom, and chooses to break it into eight pieces, which she then scatters across the world, hiding them to prevent Ganon from ever acquiring them. She then orders her faithful nursemaid Impa to go forth and seek a warrior brave enough to challenge Ganon.

As Impa roams the kingdom of Hyrule in the hope of finding a savior, Ganon learns of Zelda’s plans and has her locked up before sending his men to track down the nursemaid. Surrounded by these ruthless creatures, Impa is saved by a young boy named Link at the very moment when it appears that all is lost. As unbelievable as it may seem, Link has been chosen by the golden triangle of courage, and thus holds a part of the Triforce himself. Convinced that she has finally found the one who will save the kingdom, Impa hurries to tell him her story. Link accepts his mission to rescue Zelda without hesitation. Before confronting Ganon, however, he will have to gather the eight fragments of the triangle of wisdom, which are his only hope of gaining entry to the dungeon deep beneath Death Mountain where the Prince of Darkness hides. His quest has only just begun.

A SUCCESSFUL PREMIERE

The Legend of Zelda was released in Japan on February 21, 1986, on the Famicom Disk System, an extension that sat on top of the Famicom console and allowed it to read games from floppy disks. But this first installment of the Zelda series appeared in the familiar cartridge format when it came out for the NES the following year in the United States and Europe. The rest, of course, is history: The game made an exceptionally strong impression and became an unbelievable critical and commercial success, selling more than 6.5 million copies. It was the start of one of Nintendo’s most prestigious series, one which continues to fascinate and inspire players to this day.

THE BIRTH OF ZELDA...

Much like another little game known as Super Mario Bros., which was also a huge success on the NES, Zelda was created by Shigeru Miyamoto. It was thanks to his father, a friend of Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi, that Miyamoto— trained as an industrial engineer—was able to find a job at the company. Initially tasked with designing arcade cabinets, Shigeru Miyamoto was assigned in 1981 to direct the Donkey Kong project, which was destined to become a major hit. It was soon followed by Mario Bros. (1983) and Super Mario Bros. (1985), after which Miyamoto set to work on Zelda. He decided to give his new game a very different structure from that of Super Mario; the idea was to provide an open environment that players could explore however they saw fit. But first, let’s back up a bit in order to more fully understand the origin of this first episode of Zelda.

In 1984, two new role-playing games were all the rage. Created by Namco, the first was entitled The Tower of Druaga and took video arcades by storm. The second, Hydlide, was a highly popular RPG from T&E Soft. Like many of his peers, Miyamoto was a fan of The Tower of Druaga—so much so that he even had a coin-op machine of the game delivered directly to his office! This action RPG would turn out to be an inspiration to the entire Japanese video game industry— and Miyamoto and his future Zelda series were no exception. In December 1984, just after the release of Devil World and Excitebike, Miyamoto chose to move forward immediately with two new projects. The first one starred a plumber with an impressive mustache and a spring in his step. The second, known at the time as Adventure Title, was intended for release as a coin-op arcade game. As you may have guessed, it was Adventure Title that would go on to become the first chapter in the Zelda saga. As in The Tower of Druaga, the initial concept went no further than exploring the different levels of a citadel. At this stage of the project, there was not yet any thought of allowing the player to explore the great outdoors. However, the game already had a distinct focus on puzzles. It had even started to look like one big two-dimensional puzzle: “The game was becoming more and more puzzle-oriented,” Miyamoto explains in the official guide to A Link to the Past. “So much so that I sometimes wondered whether it was really still an adventure game.” There was even a plan to include “random” and “edit” modes, in which dungeons would be randomly generated by the console or created by the player, respectively.

The character of Link started to take shape in the first few weeks of the project: the hero of Adventure Title was soon equipped with a sword, bombs and a bow. To complete what would soon become a familiar arsenal, a variety of objects were planned, including keys, candies, flasks, a genie’s lamp, and logs. Aside from these last two accessories, we can see that the basic equipment was already in place.

As the weeks went by, however, the project and its designers’ ambitions continued to evolve. Before long, Adventure Title was no longer destined for release as a coin-op arcade game, but rather for the Famicom Disk System. For Miyamoto, the fact that Nintendo’s new peripheral allowed for rewriting data was the perfect way to allow any player to create their own dungeons and challenge others to solve them.

An amusing anecdote has it that in his efforts to use as many of the options available to him as he could, Miyamoto even briefly explored the idea of using the Zapper and the microphone of the Famicom controller. But weak sales of the infrared pistol accessory, and the lack of a microphone in Western versions of Nintendo hardware, proved fatal to some of Miyamoto’s and Takashi Tezuka’s more unusual ideas. A little-known but incredibly important figure at Nintendo, Tezuka was Miyamoto’s right-hand man, and co-director of the first episodes of the Mario and Zelda series.

As mentioned earlier, the other game that had the greatest influence on Miyamoto was Hydlide. To ensure that his nascent Zelda game would fit in with other games of the time, Miyamoto integrated new ideas inspired directly by the popular title from T&E Soft. This was how Adventure Title began to take on certain features that were quite different from those of the original project. The game was initially designed as a series of underground dungeons around what would eventually become one of the series’ best-known locations: Death Mountain. However, as we will see, this early iteration of Zelda would soon break free of this template and its influences.

The area that would come to be known as Hyrule Field was born of Miyamoto’s wish to offer players more than just a series of dungeons. His desire to break with tradition was becoming increasingly clear. The 128 KB of disk space available with the Disk System gave the men behind The Legend of Zelda an opportunity to bring their hero out from underground and offer players a kind of “open world.” So Miyamoto and Tezuka got started on designing these vast landscapes.

They began by drawing their immense map on large sheets of graph paper, and filling in even the tiniest details: “We wanted to present an above-ground world outside of the dungeons, so we added forests and lakes, and Hyrule Field started to take shape little by little,” recalls Miyamoto in the book Hyrule Historia. Exploration was on its way to becoming the heart of the Zelda experience. For Miyamoto, “it’s a game where we can explore mysterious places on our own.” “A child’s state of mind as he enters a cave all alone— the game has to capture that. As he makes his way in, he has to feel the cold air around him. He discovers a fork in the path and has to decide whether to explore it or not. Sometimes he will get lost,” he adds in an interview with Rolling Stone in January 1992. We mentioned the idea of an “open world” a moment ago, albeit somewhat hesitantly; in any event, it is clear that Miyamoto wished to offer players a more open-ended experience than in other games of the era. His main ambition was to imbue the game with a feeling of discovery—even to the point of obscuring how players should go about achieving their goals in his game. For Hiroshi Yamauchi, the president of Nintendo, this last point was something of a shock: “We can’t sell a game where the player doesn’t know where their goal is!”

Miyamoto decided to convince his boss of his approach by presenting the start of the adventure, when the hero is completely alone and unarmed. In this situation, both player and avatar feel a bit lost, and are forced to search for and discover a solution on their own. To provide players with a bit of much-needed guidance, he placed “a cave they couldn’t possibly miss” on the very first screen of the game. Miyamoto also notes that “The Neverending Story got really popular around that time. It was a world that started off with a message like: ‘Here kid, take this sword.’ In a word, it was plain,” he acknowledged in an “Iwata Asks” interview. Presumably, that’s precisely the template he had in mind when he began to design the opening moments of his game.

... OF ITS WORLD...

In creating the world of the future Zelda games, Miyamoto took inspiration from his own personal experience. As a child, and later as a teenager, he loved to explore the forest, getting lost in unfamiliar environments and discovering a lake here, a cave or an abandoned house there. It was his own sense of wonder that he hoped to capture in Zelda, even going so far as to say that he hoped to make a game that players could use as a sort of “miniature garden” to visit at their leisure. It seems that when Miyamoto visits an unfamiliar place, he prefers to discover it for himself, without seeking out any information at all about it beforehand. That’s probably the reason why, when entering a dungeon in Zelda, Link has to go through a number of different rooms before finding the map and the compass that will help him find his way to the exit. Miyamoto has said that Ridley Scott’s Legend (1985), starring a young Tom Cruise, was a source of inspiration for the game’s world. The story of this feature film was based in a classic world of fantasy: Jack, a sort of wood elf with a strong connection to the natural world, is in love with the beautiful princess Lily. But the Lord of Darkness desires her as well. The living incarnation of Evil itself, he seeks to bring darkness upon the world by killing the two unicorns who are the guardians of peace in the kingdom.

The team’s press agent came to Miyamoto with the idea of publishing a book of illustrations that would introduce the world of the game in more detail, providing an opportunity not only to present images of the game’s different characters, but more importantly, to reveal the beauty of the princess that players would be asked to save. During the discussion, the press agent brought up the example of Zelda Fitzgerald, the wife of the famous American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald. “The book project didn’t interest me at all, but I loved the name Zelda, so I asked him if we could just use the name. He said yes, and that’s how The Legend of Zelda was born,” Miyamoto explains. Although it’s surely a coincidence, it is amusing to note that Zelda is a short form of the Italian name Griselda (itself most likely of Germanie origin), which originally meant “gray warrior.”

Zelda was Miyamoto’s first game to include end credits. Before the advent of floppy disks, the Famicom didn’t have any way to display text on-screen, so movie-style credits had never been possible before. Players may be surprised to note that Miyamoto’s name does not appear in the credits! But a certain “Miyahon” does appear in the appropriate place. The other half of the dynamic duo behind this installment of Zelda, Takashi Tezuka, appears under the name of “Ten Ten.” Obscuring the creators’ names in this way was a common practice at the time, intended to prevent other companies from poaching top talent.

... AND OF LINK

As for the process of creating the character of Link, Miyamoto would not share any details until much later. In November 2012, the French journalist William Audureau asked the Japanese designer directly as part of an interview for the Gamekult website. His response: “Actually, it was Tezuka-san who designed the sprite for Link. As you know, the NES was very limited at the time, and we could only use three different colors. But we still wanted a recognizable character. What I wanted above all was for him to use his sword or his shield, and for that to be visible. So we gave him these big weapons so that you could recognize them on the screen. Then we needed to create a hero that people would be able to distinguish from his weapons, despite his small size. So we thought of giving him a long hat and big ears. That made us think of a fairy-tale character, so we went with the idea of making him look like an elf. At the time, a character with pointy ears immediately made you think of Peter Pan, and since I like Disney a lot, we started to take inspiration from that. Not only from that, of course—that wouldn’t have turned out so great... At that point, I figured that Peter Pan green was perfect for our character. Now, since we were limited to three colors and there were lots of forest environments in the game, that worked out pretty well, so we just kept going with that idea.”

With the similarities to Peter Pan now an official part of the design and a carefully considered decision on the part of the creators, the team then went even further with other analogies to J. M. Barrie’s classic work. For instance, consider the Kokiri in Ocarina of Time, a society of children (also dressed in green) who never grow up. Much like Peter Pan and his tribe of Lost Boys, they remain forever young.

When the same journalist went on to ask where their character’s name came from, Miyamoto responded: “It’s not a very well-known story, but back when we first started designing The Legend of Zelda, we imagined that the fragments of the Triforce were actually electronic chips! It was supposed to be a video game that took place in both the past and the future. Since our hero was the link between those two times, we decided to use the English word ‘link’ for his name. But ultimately, Link never went to the future, and the game remained as a work of heroic fantasy. As a matter of fact, there turned out to be nothing futuristic about it at all! [laughs]” The idea was abandoned in the end, not because of any requirements imposed by the story, but for much more prosaic reasons: this futuristic world would have required the creation of an entirely new science-fiction universe.

Finally, note that the second quest owes its existence entirely to a mistake made by Tezuka. When creating all of the game’s dungeons, he only used half of the available memory. To fill up the remaining fifty percent, Miyamoto had the idea of adding a second quest.

SOLID GAMEPLAY MECHANICS

Right from the beginning, The Legend of Zelda immerses you completely in the kingdom of Hyrule, which takes the form of an open world. You play as Link, a young hero dressed in green whose mission is to save Princess Zelda. At the time, one especially noteworthy aspect of the game was its choice of a top-down perspective, allowing players to move around in two dimensions. The player moves freely from one screen to the next, able to retrace their steps at any time. In all, the world of Hyrule as seen in this first installment consists of one hundred and twenty-eight screens. To move the story forward, Link must reconstruct the triangle of wisdom after finding its eight fragments, hidden in various dungeons where he must triumph over adversity. He will find a number of objects along the way to assist him in his journey: for example, the raft will allow him to travel to lands surrounded by water, while other found objects serve to increase his strength. Both within the dungeons and in the outside world, the core gameplay is focused on combat—no surprise when we remember that Miyamoto’s initial idea was that the dungeons would be Zelda’s only playable zones. The idea of a world map connecting the dungeons to one another was not added until later. However, this action-oriented aspect of the game is balanced by the adventure and exploration aspect: the player must continually observe the environment and keep an eye out for any secret passages or mechanisms to open hidden doors.

TWO APPROACHES TO ROLE-PLAYING GAMES

1986 saw the creation of two of gaming’s greatest classics. Without knowing it, the two Japanese publishers Nintendo and Enix had each been working to design a game based around an open world. These parallel developments culminated in the release of Zelda and Dragon Quest, the founding works of two distinct branches within the genre that would later become known as JRPGs (for “Japanese role-playing games”). Miyamoto (at Nintendo) and the duo of Yuji Horii and Koichi Nakamura (at Enix) did not have the same ambitions, to be sure: whereas Zelda was built around the idea of exploration, Dragon Quest was obviously intended as a response to American role-playing games, and especially to Wizardry on the Apple II, which Horii and Nakamura had discovered with great excitement in 1983 while attending Applefest in San Francisco. While Enix was seeking inspiration from role-playing games on microcomputers, Nintendo’s approach would turn out to be both more personal and more visceral. Although Shigeru Miyamoto, as we have seen, was not completely free of outside influences, his primary concern was to give life to an internal vision, closely tied to his own personal experience. No sooner had the JRPG genre been established than it began to diverge into two clearly distinct orientations. On the one hand, Dragon Quest offered an epic quest in which the player was responsible for controlling an entire team. To acquire the experience needed to progress in the game, the heroes were required to do battle with monsters. These clashes made use of a different on-screen representation than the one used for the map exploration phase; in addition, they cropped up at random moments during play. In the Enix title, then, the team’s increasing strength was quantified in numbers: accumulated experience allowed heroes to level up, which led to an increase in the number of points to be distributed over a long list of attributes (hit points, magic, defense, etc.). In Zelda, on the other hand, Link’s increasing strength was tied to the acquisition of specific objects, and was not expressed in numerical terms.

Another point of distinction between the two productions is accessibility. Since 1986, Miyamoto has displayed a truly unique sensibility which is nevertheless on its way to becoming a universal one, recognized by players all around the world. Zelda was extremely ambitious for its time, as we have already noted. And yet its mechanics are extremely simple ones, allowing even the youngest players to pick them up almost immediately. Unlike its “competitor,” Zelda does not provide the player with any information about the effects of player or enemy attacks; the action is presented in a transparent style. Dragon Quest, meanwhile, has a substantially richer interface in this regard, offering various menus and a multitude of options during battles—elements that Miyamoto chose not to include in Zelda. Therefore, there is no need for a system of menus to manage the heroes’ statistics, their progression, their equipment, and so on; the same is true of the sections that take place in villages or shops, in which every interaction is pared down to its simplest form. This accessibility clearly made it easier for the game to find an audience outside of Japan, thereby contributing to its worldwide success. The first Dragon Quest was not so lucky on that front: although sales were impressive within Japan (1.3 million copies), the game fell short of that success in foreign markets. In the United States, the series was known as Dragon Warrior, and the franchise didn’t make it to European stores until the eighth installment.

But lest we leave the reader with the impression that Zelda and Dragon Quest were the very first role-playing games to appear on consoles, let’s not forget examples like Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Cloudy Mountain and its sequel, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Treasure of Tarmin, which came out for Intellivision in 1982 and 1983. Still, the creations of Horii and Miyamoto were the first representatives of the JRPG genre, which has since gone on to widespread fame and launched a long line of descendants. While Dragon Quest has rightly earned its reputation as the genre’s gold standard, Zelda was the game that established the style now known as action RPGs, a genre that persisted by influencing many other publishers to produce games like Secret of Mana, Secret of Evermore, and Illusion of Time—or, more recently, Kingdom Hearts.

THE HERO

As the hero of the Zelda saga, Link’s defining look and personality traits are definitively established from the very first episode: he is a young boy dressed in green, with an elf-like appearance, whose much-vaunted courage has earned him the right to bear the corresponding triangle from the Triforce. We never see the character speak, although subsequent episodes make it clear that he can communicate perfectly well with the various inhabitants of Hyrule. His words simply never directly appear in the game (whether in written or spoken form), except for a few brief interjections. In this first Zelda game, Link is a perfect example of the classic video game hero: altruistic and brave, but without much real substance. He does have one unique feature, though: he’s left-handed! As in most games at the time, his personality is little more than a sketch, his character is rather simple, or even stereotypical—and his one, crystal-clear objective is as straightforward as can be: to save the princess. In that sense, Zelda is much like other leading games of that era such as Super Mario Bros., Ghosts ’n Goblins, and others. In order to encourage players to form an attachment to their avatar, the game also allowed them to choose their own name—as did Dragon Quest, for that matter.

THE MYTHOLOGY OF HYRULE

While the character of Link turns out to be a mere outline at this point, the mythology in which he takes part is a fairly rich one from the outset. At the heart of a perpetual conflict lies the Triforce, a mythical artifact symbolizing three values (power, wisdom and courage) that each correspond to one of the main characters: Ganon, Zelda, and Link, respectively. The backdrop to this struggle is the world of Hyrule, with a wide variety of environments (lakes, forests, mountains, etc.) inspired by fantasy stories and home to fairies and monsters. As we saw earlier, Link’s appearance also evokes the typical image of an elf, even if the word “elf” is never mentioned explicitly.

The origins, appearance and role of elves in mythology remain largely unclear. In Germanic myths, for example, they are never really described, even though they are always a “part of the scenery.” In Nordic mythology, elves even live in their own territory, known as Álfheim. Although the etymology of the word elf has been the subject of various interpretations and hypotheses, the term is generally traced back to the Indo-European root *albh, meaning white. The elf is considered to be a benevolent being with supernatural powers. Note in this connection that the mandrake, a plant traditionally associated with magical rituals, is called Alraune in German; the Proto-Germanic roots of this word are said to signify secret of the elves. Elves’ virtuous character and pointed ears were clearly the basis for the character of Link. However, the hat worn by the hero is more typically associated with gnomes or leprechauns. Fairies, meanwhile, are part of medieval Western folklore. Traditional Romanesque and Celtic imagery represents them as playing the role of protectors, lovers, or even wives; believed to be agents of fate, fairies are closely associated with notions of dreams and destiny, which are referred to in Latin with the term phantasia, originally of Greek origin. Frequently combining animal and humanoid traits, fairies are often associated with the color white (symbol of the supernatural), and are considered as protective figures. It was said that they would choose a person as their lover and take charge of their fate.

Hyrule is presented as a small kingdom. Insofar as neither the king nor his army appear in this first episode, however, Zelda alone, whom we suppose to be the king’s daughter, is the embodiment of authority. With a few rare exceptions (a couple of old wise men and merchants), Link never has the chance to meet any friendly inhabitants of the kingdom in the first episode, and he never enters a single village. His primary interactions are thus limited to battles against a variety of enemies, including a confrontation at the end of each dungeon with an iconic adversary who guards one of the fragments of the Triforce: a dragon, a giant spider, a dinosaur, and so on.

The theme of a knight battling a tyrant in a world where elves and fairies coexist with humans clearly goes back to heroic fantasy and to the literary genre of fairy tales. Originally part of the oral tradition, fairy tales take place “outside of time” and reject the notion of realism. Fairy tales rarely provide even the slightest information about the time or place in which their story is set, but they do generally display a significant concern for aesthetics. Aiming at universality, fairy tales are often based around a conflict between good and evil, with an emphasis on archetypes like the beautiful princess or the courageous prince, thus inviting the audience to focus their attention on the action. And while they often communicate a message along with certain values, fairy tales’ main purpose is to entertain. All of this applies perfectly to Zelda, even if the title of the first installment would seem to align the game more closely with legends than with fairy tales. Unlike traditional fairy tales, which come from the oral tradition, a legend is first and foremost a written story (legenda is Latin for “things to be read”); the content of a legend is still just as fictitious, but it often mingles with real elements as well. With more focus on detail than in a fairy tale, a legend is often centered on a specific person, place or event—ail elements that we find in The Legend of Zelda.

A FEELING OF GREAT FREEDOM

Pixel soup! That would be one way to summarize the graphics in games for the Famicom and competing platforms of its era. And yet, children of the 1980s can’t help but feel a bittersweet twinge of nostalgia when they remember their video gaming experiences of that time. The stories were simple, the quality of the graphics was poor, and any broader sense of setting was nonexistent. Nevertheless, players used their imaginations to transcend these limits, transforming these adventures into true interactive fairy tales. In this sense, the most important aspects of games from this era came to life inside our minds. The structure of the stories was similar from one game to the next, so much so that the ins and outs of the narrative felt completely obvious after just a few hours of play. But once again, that wasn’t what players were really concerned with. In fact, the absence of narrative and graphical detail actually served to stimulate the imagination, allowing each player to shape their own world. Video games from the era of the Famicom/NES, Master System, and their contemporaries relied much more on suggestion and implication than modern titles do. Taking advantage of how the medium has evolved, today’s games put the emphasis on showing the action in a spectacular or even bombastic way.

We can consider these 8-bit games as lying along a narrow fringe at the border between literature and cinema. Whereas literature invites the reader to construct a mental world drawn from the author’s prose, movies give viewers the chance to ride along on an intoxicating visual journey. Halfway between these two modes of expression, video games of the 1980s present simple imagery, consisting of colors and situations, which nevertheless give free rein to personal interpretation. We can go further with our cinematic analogy by comparing video games of this era to silent movies. These early films also guided the audience with music and images, while leaving their imaginations free to fill in the gaps inherent to the medium. Indeed, the films of Keaton and Chaplin relied on a similar grammar to those of video games in the NES era. With live interpretation by an orchestra or pianist to accompany the action, the music of the first movies finds an echo in the music of these video games, designed to guide the player’s path. The dialog in the first Zelda game is also similar to the title cards in silent films, thus justifying the comparison to works from the first few decades of the cinema. Finally, what better way to describe Link, the game’s hero who has no voice and expresses himself solely through gestures, than as a bridge between written stories and silent film?

Allowing players to let their imaginations roam freely reinforces the sense of freedom already built into the very design of the game. At the start of his adventure, the hero, and by extension the player, is desperately alone— alone, but therefore free to go wherever he chooses. Right from its very first installment, Zelda breaks through the boundaries that had kept players trapped inside of self-contained levels, with invisible walls like those that forced Mario to keep moving forward without ever stopping, and a dynamic screen-scrolling mechanism that created a constant sense of urgency. Although the goal is the same in both games (to free the princess), we do not feel this same sense of urgency in Zelda—because in fact, saving the captured princess is not really what motivates the player.

What truly electrifies the player and incites their passion for the game is adventure in its truest form, the kind that puts us face-to-face with ourselves and leaves us to our own fate. The game does very little to force the player’s path; from the very first second, the world of Hyrule is largely open to us. The idea of a game like Grand Theft Auto had not yet even crossed the minds of the creative forces at DMA Design, but even in this early era, Zelda was already offering the vision of an open world. Of course, that vision was still light years away from what an “open world” means to the young players of today. Nevertheless, Nintendo deserves credit for having brought to life a real feeling of freedom with this game.

A FASCINATING STORY... TOLD MOSTLY IN THE MANUAL

Nowadays, video games can draw on a toolbox of their own genre-specific codes to tell a story, or on the tools of the cinema. But in the mid-1980s, all of those tools had yet to be invented. The games of the era reflect the emergence of this new mode of storytelling, often awkward and stumbling at this early stage. As explained earlier, it was Zelda and Dragon Quest that first cleared the path for a discussion in Japan about the best way to bring engaging adventures to life through video games. In fact, however, the fable told in Zelda is not much more ambitious than the story of Mario’s mission to rescue Princess Peach. Despite this, Nintendo’s new title had a distinctly more epic character, and even if the story as presented was every bit as simplistic as that of its platformer cousin, the player taking on the role of Link was meant to be filled with a sense of courage and valor. This was a daunting challenge for the designers, who obviously had to deal with the very limited resources available on the consoles of that era. Clearly, the available capacities of the Famicom and its Disk System would not allow them to construct their story through a series of close-ups and wide-angle shots. The most obvious solution for the team was to present a brief summary of the story on the game’s title screen after a short pause. Only the broadest outlines were explained there. In addition, nothing forced players to read the synopsis; this showed that the narrative aspect was never intended to get in the way of pure gameplay, the true heart of the experience. The first few seconds of Zelda made clear the vocabulary that Nintendo would be using: with no further explanation, Link is dropped into a vast and hostile open world. The hero is completely free to take all the time he wants to accomplish his mission. Such freedom of action would be almost unthinkable today: even as players strive to break free of any and all restrictions, they still prefer that their games be structured by a consistent story to guide them and provide them with goals.

To compensate for the lack of raw computing power that prevented the creators from expressing themselves however they wished, the team had no choice but to make use of another source that was available to everyone who bought the game: the user’s manual! Utterly outdated today, this little booklet was an essential reference at the time, allowing game designers to share tips and instructions that were absent from the game itself. The gameplay mechanics in Zelda are not comparable in any way to those of today’s games. The playable tutorial sequence, designed to teach players the basic rules of the game, had not been invented yet. Reading the manual was therefore an essential step in learning to play the game. The developers took advantage of this to make the manual a full-fledged narrative tool in its own right. In reading through the booklet that came with the cartridge, the player could learn the details of the plot, alongside illustrations of the different protagonists in the adventure. These few pages were an indispensable supplement to the game, and provided information that would have been impossible to present on the consoles of the time. In addition to the manual, Nintendo decided to include a map of all the lands of Hyrule in the game box. This map was another concrete object that allowed the designers to provide the player with essential information that did not appear in the game; but more importantly, in this specific context, it served as a connection between the player and the game. The Zelda cartridge came equipped with a save chip—a first. However, each time the game was started, and after every “game over” screen, players found themselves back at the starting point of the game: any objects or rupees that they had collected would be saved, but not the place where they died. Players therefore had to make their own way back to where they had left off, and without a map, this would have been an arduous task. This is where the map provided by Nintendo turned out to be truly useful. It would be an exaggeration to call this an early instance of transmedia storytelling, a systematic approach first discussed in theoretical terms in the early 2000s by which multiple different media are used together in synergy to develop a multifaceted fictional world. Still, it is interesting to note the recent trend back towards objects, with a game like Level-5’s Ni no Kuni including a real spell book with its DS version—an apparent echo of Nintendo’s choice with The Legend of Zelda.

At the end of the text that scrolls across the screen after starting the game, the developers at Nintendo advise the player to read the manual to learn more about the world of Zelda. Nevertheless, this part of the manual was still an entirely optional narrative tool. Players who chose not to read it were not prevented from making progress in the adventure. Recall that at the time, the story underlying a video game was far from the top priority: the market primarily targeted children, and as a new medium, games focused almost exclusively on the gameplay aspect of the experience. With imagination of their own to spare, young minds could take inspiration from the clunky patterns of pixels on their cathode ray tube TVs to make up their own adventures, and turn them into magical tales.

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS

As with many Nintendo licenses that would drive the company’s success for years to come, this first installment of Link’s adventures has everything it takes to found a franchise; and indeed, it determined the course of all the Zelda games that would follow it. Right away, all of the foundations are laid. The world of Hyrule, the Triforce, and the connections between Link, Zelda and Ganon would serve as the basis for the story of most later episodes, each one tirelessly relating the struggles among the different protagonists within the kingdom, with some seeking to conquer and others to protect. The gameplay would continue to maintain a tight connection between action and exploration, along with the iconic top-down view in the 2D episodes—except for the second episode. Players loved the music as well, especially Koji Kondo’s famous theme, which fans looked forward to hearing again in each new episode. Finally, we can conclude by evoking a number of small details scattered throughout Legend of Zelda that were to become permanently associated with the series: the hidden heart containers that extend the player’s life meter; the ability to map items to controller buttons and see them on the screen; the rupees used as a local currency (although they were referred to as “rubies” in the original game manual); the compass and the map that showed the layout of a dungeon and the location of the boss; and of course the indispensable bow, bombs, boomerang, shield, and other essential accessories.

A LEGENDARY GAME

The first episode of Zelda made a huge impression when it was released. It offered players a colossal adventure in comparison to other games of its era, requiring players to explore a gigantic world—not to mention that by completing the adventure once, or by choosing “ZELDA” as the name of their hero, players could take part in a new quest, with a slightly modified world map and different dungeons. The presence of battery-powered RAM for saved games (a first for the era) was a clear indication of the size of the task that awaited young adventurers. Link’s increasing power as he collected new objects throughout the game provided a real sense of experiencing an epic quest, punctuated by battles in increasingly complex dungeons. Although the gameplay obviously feels dated today, and the narration a bit abrupt, this first installment still holds an undeniable attraction for many players. But let’s not forget how difficult this adventure was. Producer Eiji Aonuma even admits that he has never finished this episode. “I actually never got to the end of it. I think there’s practically no other game that’s more difficult than that one. Every time I’ve tried to play it, I wind up with too many ‘game over’ screens and I end up quitting. After playing the original Zelda