17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

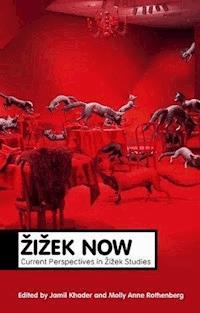

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Polity Theory Now

- Sprache: Englisch

Arguably the most prolific and most widely read philosopher of our time, Slavoj iek has made indelible interventions into many disciplines of the so-called human sciences that have transformed the terms of discussion in these fields. Although his work has been the subject of many volumes of searching criticism and commentary, there is no assessment to date of the value of his work for the development of these disciplines. iek Now brings together distinguished critics to explore the utility and far-ranging implications of iek's thought and provide an evaluation of the difference his work makes or promises to make in their chosen fields. As such, the volume offers chapters on quantum physics and iek's transcendentalist materialist theory of the subject, Hegel's absolute, materialist Christianity, postcolonial violence, eco-politics, ceremonial acts, and the postcolonial revolutionary subject. Contributors to the volume include Adrian Johnston, Ian Parker, Todd McGowan, Bruno Bosteels, Erik Vogt, Verena Conley, Joshua Ramey, Jamil Khader, and iek himself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 425

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Theory Now

Title page

Copyright page

Acknowledgments

Notes on Contributors

Part One

Introduction: Žižek Now or Never: Ideological Critique and the Nothingness of Being

1 Žižek’s Sublime Objects Now

There

Then

Now

Part Two

2 Hegel as Marxist: Žižek’s Revision of German Idealism

Absolutely Immanent

Retaining the Monarch

From Hegelian to More Hegelian

3 Žižek and Christianity: Or the Critique of Religion after Marx and Freud

A Plea for Vulgar Thinking

The Atheist Core of Christianity

The Only Truly Logical Monotheism?

From Kant to Hegel

Marx, Freud, and the Critique of Religion

Consequences and Tasks

4 Ceremonial Contingencies and the Ambiguous Rites of Freedom

Repetition and Contingency

The Lesson of Parsifal

Ritual Reticence

Part Three

5 A Critique of Natural Economy: Quantum Physics with Žižek

6 Slavoj Žižek’s Eco-Chic

Ecology and the Emancipatory Subject

Ecology without Nature

Fear and Terror

Apocalypse vs Apocalypticism

“What is to be done”?

7 Žižek and Fanon: On Violence and Related Matters

The Ambiguity of Subjective Violence Facing Objective-Systemic Violence

Self-Violence as Passage to Proper Political Subjectivization

Violence and the Question of Political Organization

For a Postcolonial Universal Politics

8 Žižek’s Infidelity: Lenin, the National Question, and the Postcolonial Legacy of Revolutionary Internationalism

Žižek and the Postcolonial: Between a Supplement and an Excremental Remainder

“Beyond the Pale of History”: Lenin, the National Question, and the Postcolonial Legacy of Revolutionary Internationalism

The Postcolonial Hypothesis: Two Words for Žižek

Part Four

9 King, Rabble, Sex, and War in Hegel

Index

Theory Now

Series Editor: Ryan Bishop

Virilio Now John Armitage

Baudrillard Now Ryan Bishop

Žižek Now Jamil Khader and Molly Anne Rothenberg

Copyright © Jamil Khader and Molly Anne Rothenberg 2013

The right of Jamil Khader and Molly Anne Rothenberg to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2013 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5370-9 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5371-6 (paperback)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6437-8 (Multi-user ebook)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6438-5 (Single-user ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Acknowledgments

The editors wish to extend their sincere thanks to all the contributors to this volume for their commitment to the success of this project. In particular, they would like to thank Slavoj Žižek for his support of and collaboration on this project. The editors also gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of the staff at Polity, especially Andrea Drugan, Lauren Mulholland, and Susan Beer.

Both of us would like to thank our families for making this project possible. Jonathan Riley has provided much-needed and appreciated support, good humor, and expertise to Molly.

Jamil would like to thank his wife, Marie B. Velez, and three daughters, Jamila M., Alana J., and Salma L., for their unconditional love, encouragement, and patience with him through the endless hours he spent working on this project, especially when Žižek’s ideas on everything contemporary became the main topic of discussion around the dinner table or on family trips.

At Stetson University, Jamil would like to thank the outgoing Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Dr Grady Ballenger, and various colleagues, especially Karen Kaivola and John Pearson, for their encouragement and support for his work. He would like also to acknowledge the assistance of Susan Connell Derryberry and Cathy Ervin at the Dupont-Ball library at Stetson University. Part of the research for his chapter in this book was supported by a summer grant from Stetson University. Molly thanks her colleagues at Tulane University, especially Dean Carole Haber, whose encouragement of her scholarship during her time as chair was particularly welcome. She also gratefully acknowledges support from the fund for her Weiss Presidential Fellowship at Tulane. Both editors thank Engram Wilkinson for his research assistance.

Notes on Contributors

BRUNO BOSTEELS is Professor of Romance Studies at Cornell University. He is the author of Alain Badiou, une trajectoire polémique (La Fabrique, 2009); Badiou and Politics (Duke University Press, 2011); The Actuality of Communism (Verso, 2011); and Marx and Freud in Latin America: Politics, Psychoanalysis, and Religion in Times of Terror (Verso, 2012). He is also the author of dozens of articles on modern Latin American literature and culture, and on contemporary European philosophy and political theory.

VERENA ANDERMATT CONLEY is Long-Term Visiting Professor of Literature and Comparative Literature and of Romance Languages and Literatures at Harvard, where she teaches courses on Parisian cityscapes, transformations of space in contemporary culture, the city, technology, existential literature, and cultural theory. Her recent books include: Spatial Ecologies: Urban Sites, State and World-Space in French Critical Theory (Liverpool University Press, 2012); Littérature, Politique et communisme: Lire “Les Lettres françaises,” 1942–72 (New York: Lang, 2005); The War with the Beavers: Learning to be Wild in the North Woods (Minnesota, 2003; 2005); and Ecopolitics: The Environment in Poststructuralist Thought (Routledge, 1997). She is also the editor of Rethinking Technologies (Minnesota, 1993; 1997).

ADRIAN JOHNSTON is a Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and an Assistant Teaching Analyst at the Emory Psychoanalytic Institute in Atlanta. He is the author of Time Driven: Metapsychology and the Splitting of the Drive (2005); Žižek’s Ontology: A Transcendental Materialist Theory of Subjectivity (2008); and Badiou, Žižek, and Political Transformations: The Cadence of Change (2009); all published by Northwestern University Press. He has three books scheduled for publication over the course of the next year: Self and Emotional Life: Merging Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Neurobiology (co-authored with Catherine Malabou and forthcoming from Columbia University Press); Adventures in Transcendental Materialism: Dialogues with Contemporary Thinkers (Edinburgh University Press); and The Outcome of Contemporary French Philosophy: Prolegomena to Any Future Materialism, Volume One (the first installment of a trilogy forthcoming from Northwestern University Press). With Todd McGowan and Slavoj Žižek, he is a co-editor of the book series Diaeresis at Northwestern University Press.

JAMIL KHADER is Professor of English and Director of the Gender Studies Program at Stetson University. He is the author of Cartographies of Transnational Feminisms: Geography, Culture, Identity, Politics (Lexington, 2012) and numerous publications on transnational feminisms, supernatural fiction, and literary theory that have appeared in various national and international literary journals including, among others: Ariel, Feminist Studies, College Literature; MELUS; The Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts; The Journal of Postcolonial Writing; The Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies; The Journal of Homosexuality; and other collections.

TODD McGOWAN teaches critical theory and film at the University of Vermont. His books include: Out of Time: Desire in Atemporal Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2011); The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (State University of New York Press, 2007); and with Paul Eisenstein, Rupture: On the Emergence of the Political (Northwestern University Press, 2012).

IAN PARKER was co-founder and is co-director (with Erica Burman) of the Discourse Unit (www.discourseunit.com). He is a member of the Asylum: Magazine for Democratic Psychiatry collective, and a practicing psychoanalyst in Manchester. His research and writing intersects with psychoanalysis and critical theory. He is a member of the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research, the London Society of the New Lacanian School and the College of Psychoanalysts, UK. His books include: Revolution in Psychology: Alienation to Emancipation (Pluto, 2007); and Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Revolutions in Subjectivity (Routledge, 2011).

JOSHUA RAMEY is Visiting Assistant Professor at Haverford College. His work covers issues in contemporary continental philosophy, aesthetics, and philosophy of religion. He is the author of The Hermetic Deleuze: Philosophy and Spiritual Ordeal (Duke University Press, 2012). He has also published work on figures such as Žižek, Adorno, Warhol, Cronenberg, Deleuze, Badiou, and Rancière in such journals as Angelaki, Discourse, SubStance, and Political Theology.

MOLLY ANNE ROTHENBERG is Professor of English at Tulane University and a practicing adult psychoanalyst. Her publications include: The Excessive Subject: A New Theory of Social Change (Polity 2009); and Perversion and the Social Relation (Duke University Press 2003, co-edited with Slavoj Žižek and Dennis Foster). Her work has appeared in Critical Inquiry, PMLA, ELH, and the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, among others. A chapter on Jacques Rancière’s work is forthcoming in Modernism and Theory (Routledge), edited by Jean-Michel Rabaté. At present, she is working on a book manuscript that highlights the reactionary positions implicit in diasporic identifications.

ERIK VOGT is Gwendolyn Miles Smith Professor for Philosophy at Trinity College (USA), as well as Dozent for Philosophy at University of Vienna (Austria). He is the author and (co-)editor of fourteen books and has translated six books by Žižek into German. His most recent publications include: Slavoj Žižek und die Gegenwartsphilosophie (Vienna – Berlin: Turia + Kant, 2011); Monstrosity in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and Philosophy, ed. with G. Unterthurner (Vienna – Berlin: Turia + Kant, 2012); Antirassismus – Antikolonialismus – Politiken der Emanzipation: Zur Aktualität von Jean-Paul Sartre und Frantz Fanon (Vienna – Berlin: 2012, Turia + Kant, forthcoming).

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK is a Hegelian philosopher, Lacanian psychoanalyst, and Communist social analyst. He is a researcher at the Institute of Humanities, Birkbeck College, University of London. His latest publications include: Less Than Nothing and The Year of Dreaming Dangerously (both London: Verso Books 2012).

Part One

IntroductionŽižek Now or Never: Ideological Critique and the Nothingness of Being

Jamil Khader

Arguably the most prolific and widely read philosopher of our time, Slavoj Žižek has made significant interventions in many disciplines of the human and natural sciences. Appropriating Lacanian psychoanalysis as a privileged conceptual fulcrum to reload German idealism (Hegel) through Marxism and, more recently, Christianity, Žižek has written extensively (and in several languages) on a dizzying array of topics that include global capitalism, psychoanalysis, opera, totalitarianism, cognitive science, racism, human rights, religion, new media, popular culture, cinema, love, ethics, environmentalism, New Age philosophy, and politics. His interdisciplinary oeuvre juxtaposes diverse fields and disciplines in many surprising ways, regularly springing unexpected twists and reversals on the reader. He not only subjects these disciplines to an ideological metacritique of the nature of knowledge itself, but also engages these disciplines through a parallax view, the “confrontation of two closely linked perspectives between which no neutral common ground is possible” (Žižek 2006: 4). For Žižek, rubbing these disciplines against each other does not produce a totalizing synthesis of opposites but rather allows for articulating the gaps within and between these fields through the Hegelian method of negative dialectics that clears a space for elaborating new responses to the underlying antagonism.

Who is this Žižek? What is his work all about? What are the broader theoretical trajectories that frame his work? How can his popular appeal as a philosopher and public intellectual be explained? Slavoj Žižek was born on March 21, 1949 in Ljubljana, Slovenia, the northernmost republic in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and grew up under the rule of Marshal Josip Broz Tito, who served as president from 1953 to 1980. Although he was a founding member of the Cominform, Tito defied Soviet hegemony and developed an independent path to socialism, while also suppressing particularistic national sentiments in the name of a unified Yugoslavia. The relative cultural freedom in Tito’s “second Yugoslavia” has been credited with having an everlasting impact on Žižek’s intellectual development and career, allowing him to define his position on the margins of dominant national culture, in critical distance from and resistance to the party line and its institutions or any other mainstream orthodoxy.1 In this semi-liberal environment, Žižek developed an obsession with and an appreciation for Western cultural commodities, particularly Hollywood films and detective fiction written in English, over and against cultural and literary products in his own country, which he considered to be either Communist or nationalist propaganda. Nonetheless, as Ian Parker notes in his contribution to this volume, living in “the times of lies” that characterized the regime left its indelible mark on Žižek’s thought, which was “intimately linked to sarcastic and then increasingly open opposition, a politics of ideology critique that was smart enough not to believe that it spoke in the name of any unmediated authentic reality under the surface.” After abandoning his teenage idea of directing films, as he says in a recent interview with the Telegraph, Žižek realized by the age of seventeen that he wanted to be a philosopher. He thus obtained an undergraduate degree in philosophy and sociology in 1971, and a Master of Arts in philosophy in 1975 from the University of Ljubljana, writing a 400-page thesis on French structuralism, which the authorities deemed to be ideologically suspicious, costing him a teaching position he was promised at the university. In fact, as Žižek recalls in a conversation with Glyn Daly, he “had to write a special supplement because the first version was rejected for not being Marxist enough” (Daly 2004: 31).

For the next two years, Žižek served in the Yugoslav army and translated German philosophy to support his wife and son, until 1977, when he took up a “humiliating job,” as he states in the film Žižek!, at the Central Committee of the League of Slovene Communists. In these years, Žižek founded, with Mladen Dolar and Renata Salecl, who became his second wife, the Society for Theoretical Psychoanalysis in Ljubljana, served on the editorial board of a journal called Problemi, and published a book series called Analecta. In 1979 Žižek took a job as Researcher at the University of Ljubljana’s Institute for Sociology, where he “had the freedom to develop [his] own ideas” in philosophy and Lacanian psychoanalysis and earned his first Doctor of Arts degree in philosophy in 1981, writing his dissertation on German Idealism. In the same year, he traveled to Paris for the first time where he met Lacan’s son-in-law, Jacques-Alain Miller, who invited Žižek and Dolar to attend an exclusive thirty-student seminar on Lacan at the École de la Cause Freudienne, analyzed him, and secured a teaching fellowship for him as visiting professor at the Department of Psychoanalysis at the Université Paris-VIII. Four years later, Žižek successfully defended his second doctoral dissertation, a Lacanian reading of Hegel, Marx, and Kripke, with Miller, but the latter refused to publish Žižek’s dissertation in his own publishing house, forcing Žižek to publish it outside mainstream Lacanian circles.

Meanwhile, Žižek became more involved in the oppositional democratic politics back in Slovenia, writing for the radical youth magazine Mladina, publicly resigning from the Communist party in protest at the trial of journalists associated with that magazine, cofounding the Liberal Democratic Party, and running as its candidate in the first multi-party presidential elections in the country in 1990, but narrowly missing office. He served as the Ambassador of Science for the republic of Slovenia in 1991, and continues to serve as an informal advisor to the Slovenian government. Žižek is currently a Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Ljubljana, the International Director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities in London, a returning faculty member of the European Graduate School, and since 1991 he has also held visiting positions at different universities in the US and the UK. He also serves on the editorial board of the Analecta series in Slovenia, and helped establish two series, Wo es war for Norton, and SIC for Duke University Press, in German and English.

Žižek burst onto the intellectual scene in Western Europe and North America in 1989 with the publication of his first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology, in a series edited by the Argentinean philosopher Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. In his psychoanalytic examination of human agency and ideology, Žižek combined his pioneering reading of Freud and Marx with his Lacanian analysis of ideological fantasy, his encyclopedic knowledge of popular culture, his non-standard approach to Hegel, and his Hegelian reading of Christianity. The effects of this dazzlingly eclectic text were unprecedented, and the fact that Žižek was at the time a virtually unknown author, at least among English-speaking audiences, added to the intriguing appeal of the book among the general public. Moreover, Laclau’s preface to the book almost instantly secured Žižek’s international reputation within leftist circles worldwide. Indeed, the book resonated deeply with many readers around the world who were committed to the possibility of reinvigorating both the radical core of revolutionary politics and the relevance of philosophy for politically engaged readers.

Since the publication of The Sublime Object of Ideology in 1989, Žižek has published over fifty books, edited several collections, and published numerous articles. He has also written books in German, French, and Slovene, and many of his works have also been translated into twenty different languages. Žižek’s increasingly expanding oeuvre can be divided into four main categories. First, introductions to Lacan through popular culture and everyday examples, as seen in Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jaques Lacan through Popular Culture (1991); Enjoy Your Symptom: Jacques Lacan in Hollywood and Out (1992); and more recently How to Read Lacan (2006). Second, theoretical works that intertwine philosophy and psychoanalysis to develop a critique of ideological fantasy and a political theory of agency and subjectivity: this category includes books such as The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989); For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (1991); Tarrying with the Negative: Kant, Hegel, and the Critique of Ideology (1993); The Metastasis of Enjoyment (1994); The Indivisible Remainder: An Essay on Schelling and Related Matters (1996); The Abyss of Freedom (1997); The Plague of Fantasies (1997); The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology (1999); The Fright of Real Tears (2001); On Belief (2001); Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism (2001); Organs without Bodies (2004); The Parallax View (2006); and Living in the End Times (2010). Third, writings that address current political and social events such as Welcome to the Desert of the Real!: Five Essays on September 11 and Related Dates (2002); Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle (2004); Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (2008); In Defense of Lost Causes (2008); and First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (2009). And fourth, works that appropriate the radical atheist core of Christianity including: The Fragile Absolute (2000); The Puppet and the Dwarf (2003); and The Monstrosity of Christ (2009). His most recent tome is titled, Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism (2012), in which he presents his own unique interpretation of Hegel and calls for the return to a Hegelianism that exceeds Hegel’s accomplishments and repeats, to paraphrase his typical phrase, what in Hegel that is more than Hegel himself.

This prolific output, its political undercurrents and advocacy of anti-capitalist struggle, has put Žižek in the spotlight of international media. He has thus been the subject of a documentary called Žižek! The Movie (2005) by Astra Taylor; he was also featured, together with seven other professors at American universities, in her film, Examined Life. There are also two films featuring formal presentations by Žižek – The Reality of the Virtual (2004) by Ben Wright and The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006) by Sophie Fiennes. Žižek has also been a regular guest on Al Jazeera TV in English and the BBC, and he has maintained a tireless speaking schedule around the world. No wonder, then, that critics have dubbed him the “giant of Ljubljana” and the “most formidable philosophical mind of his generation” (Harpham 2003: 504) and that he is usually referred to in the popular media as the “Elvis Presley of cultural theory” and an “intellectual rock star.”

But his increasingly expanding work, international fame, and charismatic presence have also been the source of consternation and concern for Žižek. For one, his tendency to use humor in his lectures has endeared him to the public outside the realm of academic audiences; but it also gives some critics reason to trivialize and dismiss his work as entertainment, with some even going so far as to describe him as a “comedian.”2 Žižek himself laments in Taylor’s Žižek!: The Movie how for some “making me popular is a defense against taking me seriously.” Furthermore, because of the speed with which he writes and publishes, almost a monograph per year, and as a result of his idiosyncratic recursive writing style, some critics have expressed concerns that Žižek’s work is unsystematic, repetitive, and contradictory. These critics miss the point, for as Ian Parker argues in this volume that despite his appropriation of Lacan to reload Hegel through Marxism, Žižek insists that such a theoretical elaboration “should be open, negative, and indeterminate.” Laclau’s preface to The Sublime Object of Ideology, moreover, inadvertently helped to define, for better or worse, some of the popular myths about Žižek’s writings among the general readership. About the book itself, for example, Laclau writes:

It is certainly not a book in the classical sense; that is to say, a systematic structure in which an argument is developed according to a pre-determined plan. Nor is it a collection of essays, each of which constitutes a finished product and whose ‘unity’ with the rest is merely the result of its thematic discussion of a common problem. It is rather a series of theoretical interventions which shed mutual light on each other, not in terms of the progression of an argument, but in terms of what we could call the reiteration of the latter in different discursive contexts. (Žižek 1989: xii)

The fact that Žižek continues to revisit and elaborate on the main issues he raised in his first book in English testifies precisely to the systematic nature of his work. Furthermore, Žižek’s engagement with fleeting political and social events cannot be properly understood without situating his arguments in the context of the general trajectories and presuppositions of his theoretical writings. Indeed, Žižek’s philosophical edifice, which he has been building and refining book by book, in dialogue and debate with many intellectuals, critics, and philosophers from all over the world, remains narrowly focused in its theoretical framework and concerns.

Although his work has been the subject of many volumes of searching criticism and commentary, to date there has been no assessment of its value for the development of the human and natural sciences. Addressing this lack, Žižek Now seeks to explore the utility and far-ranging implications of Žižek’s thought to various disciplines and provide an evaluation of the difference his work makes or promises to make in different fields. The volume offers chapters on quantum physics and Žižek’s transcendentalist materialist theory of the subject, Hegel’s absolute, materialist Christianity, postcolonial violence, eco-politics, ceremonial acts, and the postcolonial revolutionary subject. The contributors chart broad trajectories in Žižek’s work, showcasing the innovations that his work has inaugurated, mapping continuities and departures in it, and relating it to broader theoretical trends in these fields. While some of these authors use his theoretical framework as a tool for engaging his work in its own terms (McGowan, Bosteels, and Ramey), others assess Žižek’s position on a recurrent theme in his oeuvre either in the context of the current debates in these fields or in dialogue with prominent thinkers in them (Johnston and Conley). Some find in Žižek’s work an opportunity to intervene in a field that he does not address (Vogt and Khader). Rather than re-presenting his work as the lone voice in the desert of academe, therefore, this volume engages his work in relation to the hegemonic trends of the postmodern zeitgeist, be it the universalized historicism of cultural studies, the evolutionism of cognitive science, or the hermeneutics of suspicion of literary theory.

Following this Introduction, in the second chapter of Part One of this volume, the renowned Žižekian critic Ian Parker overviews the three major theoretical trends, within which Žižek frames his work namely, Marxism, Lacanian psychoanalysis, and Hegelian dialectics. Although Parker takes issues with Žižek’s polemical style, he considers him a “thinker for our times” whose interventions gain special urgency under contemporary conditions of the global capitalist crisis and concomitant forms of global “psychologization,” a concept Parker borrows from the recent work of Jan De Vos, who uses it to name the various technologies, by which every aspect of our thoughts and experiences is adapted, co-opted, and reintegrated within capitalist rationality (De Vos 2011). In Parker’s view, Žižek utilizes the internal fissures within the three theoretical currents of his work as well as the contradictions among them to make possible not only “another world,” but also “another subject,” a project that must necessarily stay incomplete. Parker thus argues that Žižek’s oeuvre remains concerned from beginning to end with the “conditions of impossibility,” of negativity and nothingness at the core of social field that not only frustrate any desire for unity or wholeness, but whose contradictions will also “at some point explode and change the symbolic coordinates within which we choose and act.” Exploring the ramifications of this nothingness to Žižek’s work, Parker concludes by discussing five targets of Žižek’s ideological critique – psychologistic assumptions about the integrity of the self, the exhortation to achieve liberation by de-repressing libidinal energy, the calls for an authentic community, the search for the hidden but true meaning, and the celebration of the free play of narrative. His discussion provides a succinct summary of the major themes and issues that the other contributions to this volume elaborate on in their critical engagement with Žižek’s multifaceted work.

In Part Two of this collection, Todd McGowan, Bruno Bosteels, and Josh Ramey establish the grounds for understanding Žižek’s critical theory of dialectical materialism. Utilizing Žižek’s theoretical framework as a tool for engaging his work in its own terms, McGowan, Bosteels, and Ramey provide the starting point for the critical examination of Žižek’s appropriation of Lacan to reactualize German Idealism, Marxism, and Christianity, and for assessing the revolutionary potential – and limitations – of Žižek’s thought for philosophy, religion, and politics. Todd McGowan takes his start in Žižek’s dialectical materialism as grounded in German idealism, but he focuses especially on the “dialectical” dimension of Žižek’s thought which is uniquely predicated on Hegel’s “hidden political core” as the basis for formulating an anti-utopian emancipatory politics. Hegel’s absolute, in particular, allows McGowan to highlight Žižek’s complete identification of political struggle with the recognition of the fundamental antagonism as it reveals itself under conditions of global capitalism. The absolute provides Žižek with an insight into “antagonism without escape,” since the absolute makes it clear that “there is no possible reconciliation without the acknowledgment of a fundamental self-division that no amount of struggle can ever overcome.” McGowan thus examines Žižek’s retroversive reading of Hegel as a critic of Marx, for it is only through Hegel, as Žižek sees it, that we can discern “what is in Marx (the revolutionary potential) more than Marx.” In particular, the Hegelian theorization of antagonism as the rejection of the oneness of being underwrites Žižek’s Hegelian critique of Marx’s fatal conviction that the means of production themselves are self-identical, when in fact they are not. In Žižek’s hands, moreover, Hegel’s absolute radicalizes Marx’s revolutionary philosophy, by offering a basis for the politicization of the subject, since political revolution constitutes a “new way of seeing that foregrounds the ubiquity of antagonism and thus of subjectivity.” According to Žižek, in short, the political act forces the subject to confront this irreducible antagonism and refuses any attempt at overcoming the structural fact of the antagonism. This is the only way that neo-liberal democracy can be subjectivized, by lashing out at ourselves and at our faith in democracy as the end of history, to allow for the radical interrogation of global capitalism. Hegel, McGowan concludes, “enables Žižek to retain violence (and thus antagonism) within his politics without succumbing to the logic of the gulag.”

Bruno Bosteels engages Žižek’s writings on religion, interrogating the political limitations of Žižek’s materialist defense of Christianity’s perverse atheist core – that there is no big Other that can determine the ‘objective meaning’ of our actions – as a legacy worth fighting for and retrieving in its organized form before it had congealed into an institutionalized ideology. The problem with Žižek’s materialist defense of Christianity, Bosteels argues, is that it remains confined within a proper philosophical matrix through the triangulation of Hegel and Lacan by way of Christianity. Žižek’s Lacano-Hegelianism, Bosteels charges, “remain strictly speaking at the level of a structural or transcendental discussion of the conditions of possibility of subjectivity as such.” What remains missing in Žižek’s materialist defense of Christianity is a genealogical or historical materialist investigation that places the “politics of the subject in a permanent tension field between theory and history.” To begin filling in this gap in Žižek, Bosteels examines the ways in which his perverse-materialist reading of Christianity revises, and perverts, Marx’s and Freud’s critiques of religion which are, nonetheless, not a match for the perverse core of Christianity. For Žižek, according to Bosteels, Marx “disavows the fact of human finitude in the name of an absolute subject-object of history,” while Freud “acknowledges and names this traumatic dimension of finitude,” only to send us “back to a cosmic-pagan battle of life and death, Eros and Thanatos.” As an alternative to Žižek’s limited philosophical approach, moreover, Bosteels suggests the development of a historical and genealogical agenda, along the lines of the genealogical work of the Argentine Freudo-Marxist León Rozitchner, which can clear a space for exposing the extent to which theorization of political subjectivity remains embedded and inscribed within Christian theology. Through a close reading of Saint Augustine’s Confessions, Bosteels contends, Rozitchner did not only demonstrate that capitalism would not have developed the way it did without Christianity, but that he also “continues to expand the historical overdeterminations of the subject in the long run.” This is the only way, he suggests, that the subject’s real transformation can be rendered possible.

In the last chapter of Part Two, Joshua Ramey takes up a specific dimension of Žižek’s political philosophy namely, the potential of liturgical-ceremonial forms in sustaining freedom and authentic revolutionary acts. Drawing on the particular modality of virtual temporality that Gilles Deleuze refers to as the “pure past,” Ramey articulates how Žižek proposes “the free Act does not so much open a totally new present as retroactively alter the nature of the past, ‘retroversively’ determining which pasts now matter, or what in the past is now determinative.” It is only after the fact, that is, that a truly free Act can be discerned. Although for Žižek the rediscovery of contingency in the past leads to the reconfiguration of history, Ramey still detects an ambiguity in Žižek’s understanding of freedom in relation to the ability of the subject to realize her participation in the unfolding of free acts. To activate or realize freedom, therefore, Žižek argues for the importance of liturgical-ceremonial gestures for authentic revolutionary acts as “an encounter with the ‘zero-level’ of sense.” Ramey thus notes that for Žižek “ritual and ceremonial acts seem to offer an immanent model of continuity between the transcendental sources of freedom and the shape of concrete historical acts,” for the repetition of certain formalities, which cannot simply be wholly arbitrary, realizes the truth of a political movement. Hence, Ramey points out, Žižek has recently affirmed the power of liturgical-ceremonial acts to serve as an authentic dimension of communist culture, foregrounding the ability of liturgical gestures to politicize enjoyment as the “ceremonialization of everyday life.” While it is impossible to guarantee a “stable relationship to virtual potencies of emancipation, love or justice,” Ramey contends, the source of the revolutionary act and the substance of all ceremony for Žižek can be located in the “fecundity of the virtual itself.”

In Part Three of this book, Adrian Johnston, Verena Andermatt Conley, Erik Vogt, and Jamil Khader highlight specific provocations in Žižek’s work that prove fruitful for guiding us to unexpected areas of inquiry in the context of current debates in quantum physics, media studies, ecological studies, and postcolonial studies. The renowned Žižek critic Adrian Johnston examines Žižek’s appropriation of quantum physics, in order to reassess his materialist deployments of natural science and to disprove that any theory of the free subject has to offer a thoroughly materialist account. While Johnston believes it is important for Žižek to ground his ontology partially in scientific theory, he criticizes Žižek for failing to offer a cogent transcendentalist materialist theory of the subject, since Žižek is insufficiently careful in moving between the scientific and the ontological. He thus questions Žižek’s recourse to quantum physics on general philosophical grounds, stating that the “theoretical form of his extensions of quantum physics as a universal economy qua ubiquitous, all-encompassing structural nexus (one capable of covering human subjects, among many other bigger-than-sub-atomic things) is in unsustainable tension with the ontological content he claims to find divulged within this same branch of physics (i.e., being itself as detotalized and inconsistent).” In other words, Žižek risks turning quantum physics into the One-All of a big Other in stark violation of his own ontology. In fidelity to what he refers to as a “Žižekian ontology of an Other-less, barred Real of non-All/not-One material being,” Johnston offers an alternative account of subjectivity grounded in biological emergentism, coupled with a Cartwrightian “nomological pluralism.”

Verena Andermatt Conley considers the radical as well as the conservative dimensions of Žižek’s “eco-chic,” questioning Žižek’s attitude toward nature and his reliance on outdated rhetorical oppositions in his critique of New Ageism. While she criticizes Žižek for his selective appropriation of ecological debates and for his vague deployment of the term political ecology, Conley finds Žižek’s focus on political ecology compelling, since he addresses problems of nature alongside with those of the “part of no part,” or the excluded from the global capitalist system by way of an elaboration of the idea of revolutionary-egalitarian justice. She writes, “Considering ecology in the context of the new emancipatory subject, Žižek holds that contra the present ideological mystification of ecology – in effect contra the limited lessons of a balanced, harmonious nature that many of its new-age adepts impose with righteous sanctimony – a candid view of an ecology that works against itself can come about only when we first think the immense emancipatory potential of the urban slum dwellers.” The value of Žižek’s contribution to environmental studies can thus be attributed not only to his recognition of the world’s massive ecological catastrophes, but more importantly to his theorization of the ecology as a collective experience, “even as a rehabilitation of a “communism” cleansed of its capitalist – and communist – mystifications, that is, for a worldwide effort to build a common that includes a redistribution of resources.” Indeed, Conley maintains, for Žižek a true ecology cannot be thought without socialism or even without communism, since ecology coincides with the communist call for a genuine collective experience.

In the last two contributions of Part Three, Erik Vogt and Jamil Khader address the utility of Žižek’s thought for postcolonial studies, an area Žižek does not address explicitly but which, in these encounters, offers new vistas of intellectual inquiry in both Žižek studies and postcolonial studies. Erik Vogt stages an encounter between the conceptions of emancipatory universal politics in the work of the Martinique psychoanalyst and revolutionary Frantz Fanon and Žižek, tracing the various parallels and correspondences in their views on the controversial topic of violence that continues to haunt leftist politics in the West. Even though Fanon and Žižek employ distinct theoretical frameworks, Vogt argues, they still “converge in a trenchant critique regarding the perceived dissimulation of the systemic, objective violence central to the capitalist (neo)-colonialist system – a dissimulation that is generated in large part by depoliticizing representations of different manifestations of subjective violence.” After all, Žižek himself has advocated a return to the anti-colonial “problematic of Frantz Fanon,” as a way to foreground the potential inherent in subjective forms of violence to become sites of radical re-politicization of certain socio-political impasses, even though this violence can be manifested in the form self-violence (“self-beating”) on the part of Fanon’s “wretched of the earth” and Žižek’s “part of no part.” Vogt also notes that for both Fanon and Žižek, this violence facilitates the emergence of alternative modalities of collective political subjectivization which require the development of specific political organizations that can stabilize proper universal politicization, so as not to revert into mere spontaneous voluntarism. Finally, Vogt argues that both Fanon and Žižek envision a new type of postcolonial humanity that is grounded in the recognition that “the gap in their self-identity is precisely the universal separating them from themselves – the space in which new concepts of humanity have to be worked out.”

In the last chapter of Part Three, Jamil Khader argues that we can salvage Žižek’s call to repeat Lenin by recuperating an important dimension of Lenin’s revolutionary pedagogy, namely, Lenin’s mediation of the national question and his increasing faith in the capacity of the subjects of colonial difference to serve as the vanguard of revolutionary internationalism. He thus argues that if Lenin is to be repeated today, “postcoloniality should (retroactively) be considered one of those causal nodes around which a Leninist act is formed,” for Lenin’s revolutionary politics can be seen as being over-determined in a retroactive endorsement of the postcolonial link that will determine the future of revolutionary internationalism. Nonetheless, Khader takes Žižek to task for obliterating the history of the national liberation movements in the postcolonial world and for foreclosing the possibility of the construction of the postcolonial as the subject of history and revolutionary internationalism. He attributes this missing link in Žižek’s revolutionary politics to his understanding of the postcolonial which is fraught with ambivalence as to the status of the postcolonial under contemporary conditions of global capitalism – he considers the postcolonial in terms of either its function as an ideological supplement to global capitalism or its position as capital’s excremental remainder. Khader thus concludes that “Žižek’s infidelity to this other/wise Lenin notwithstanding, a genealogy of the position of postcoloniality in Lenin’s work can retroactively foreground the exclusion in Žižek’s revolutionary politics, clearing a space for its politicization.”

In Part Four of this collection, Slavoj Žižek offers an original contribution that responds, directly and indirectly, to the major themes and concerns that were raised in this collection. If Žižek seems to shift his position on some of the issues under consideration in this collection, we should remember that, as he says in an interview, we ought not be afraid to change our positions, since repetitions can reveal new possibilities over time.3 It is in this new field of (im)possibilities that Žižek’s work opens up for us that we should seize this Žižekian moment, now or never.

Notes

1 This biographical sketch of Žižek’s life draws on information gleaned from Myers 2003: 6–10, Parker 2004: 11–35, and various interviews, including the ones with Glyn Daly in his Conversations with Žižek (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2004). It is important to note that Myers and Parker take completely opposite views about the ways in which the modern history of Yugoslavia shaped Žižek’s intellectual and ideological development.

2 After describing his appearance – his beard, proletarian wardrobe, his accent, and his “accessible absurdity,” Rebecca Mead states that Žižek might appear like a serious leftist intellectual, but that in fact he is more like a “comedian.” See Rebecca Mead, “The Marx Brother: How a Philosopher from Slovenia became an International Star,” The New Yorker May 5, 2003: 38. This essay can also be accessed on Lacanian ink @ http://www.lacan.com/ziny.htm.

3 Interview with Fabien Tarby, quoted in Conley in this volume.

1

Žižek’s Sublime Objects Now

Ian Parker

Slavoj Žižek is a radically divisive conceptual activist. Juxtaposition of academic argument in dense difficult explorations of a wide range of philosophical themes with paradoxical funny excursions into popular culture makes his work into something disturbing. It forces his readers to take sides, and to take sides with him or against him. His theoretical activity is always configured as an intervention, and rare moments of descriptive explanatory prose invariably twist rapidly into cutting polemic. He is a thinker for our times even when he is wrong, and he identifies deadlocks even when he cannot break through them. But where does this naming and refusal of reigning categories of thought, of dominant symbolic forms come from, what resources does it borrow and turn against itself, and where is it going now?

There

A first predictable and reductive way of answering such questions would be to trace the trajectory of Žižek himself from being a student of philosophy at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia in the late 1960s to researcher in social theory, with a master’s degree thesis in 1975 on “The Theoretical and Practical Relevance of French Structuralism,” a detour through Frankfurt School tradition psychoanalytic theory, and a doctorate in 1981, before arriving in Paris shortly afterwards. His work had already raised suspicions about his political trustworthiness in what was then still part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and he had failed, as a consequence of these suspicions, to obtain a permanent academic position in the university.

His time in Paris, with a second doctorate in psychoanalysis in 1986, a brief analysis with Jacques-Alain Miller and a first major book (in French) on Hegel and Lacan, prepared him for a return to Slovenia, where he stood as presidential candidate for the Liberal Democratic Party in 1990. By now his first book in English The Sublime Object of Ideology (Žižek 1989) was already starting to make an impact, partly through the patronage of UK-based “post-Marxist” political discourse theorists (Laclau and Mouffe 1985). Insofar as it is possible to look back at his earlier more critical-theoretical psychoanalytic interventions into the work of Lasch (1978) on the “culture of narcissism,” for example, we can then see Žižek (1986) anticipating themes that were to erupt into full view in 1989. The first English-language book and a stream of lengthy elaborations of a circuit around Lacan, Hegel, and Marx since have provoked new research questions and, more importantly, mobilized a new generation of academics around questions of political action.

One might say that Žižek is a consummate political operator, rhetorician, and self-publicist, but to arrive at that as an explanation for his popularity now would precisely to be trapped in the ideological forms that he is trying to dismantle. That is, to treat this particular individual as the locus of all the now politically charged lines of argument that we might debate as being “Žižekian” would be to remain bewitched by the figure of the gifted genius, which is surely one of the sublime objects – Lacan’s “objet petit a” – that fascinate us, and which we aim to emulate or subject ourselves to in capitalist society. And, when we are not enthralled by such an individual – the individual as such a powerful object and model of self-hood, which operates as an essential part of the machinery of identification – we can then be just as tempted to find the source of all failures of the argument in the faults of this self-same individual. In the logic of admiration and identification that Lacan (2006) described as running along the line of the imaginary, disappointment focused on the one who fails us overlooks where the real failures are. The bare bones of this biographical account of where he is coming from do not do justice to the history which bears him, and us.

So let us take another path – of the kind elaborated in Žižek’s reading of Hegel – after this first step which was in error, into something closer to the truth. To do that we have to say something about what is sometimes, just as mistakenly as focusing on the individual, called the “context” for his work (Parker 2004). At that very moment in the 1970s when Žižek was gathering the conceptual resources for his later work, for what some would like to see as the Žižekian system, the political system around him was beginning to rupture. There are two things to note about this process of social decomposition that the Right now glories in as the end of communism marked by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The first is that Yugoslavia declared itself to be “socialist,” even to be from the 1950s a system of democratic “socialist self-management,” but was nothing of the sort. The Tito bureaucracy was a form of state-management, and with a little more flexibility and few more cracks in which those who were sceptical could survive and even, to some small extent, organize. However, despite the break with Moscow and the geographical and political location of Yugoslavia as a buffer-zone between the West and Eastern Europe, the regime was still Stalinist in character. The proclaimed unity of the federal republic was the cover for all manner of tactics of divide and rule, including on ethnic and quasi-nationalist grounds, well before the civil wars of the 1990s, and the supposed toleration of dissent was the excuse for insidious monitoring of the population and enforcement of party rule.

Žižek’s writings in the 1980s and 1990s are peppered with jokes which speak of what it was like to live in such conditions, of the lies which had to be endorsed in order to survive, especially when one was part of the cultural apparatus, which academic production of social research in the university certainly was. There is another side of this condition of living in a time of lies, of course, which only became evident when the system collapsed and Slovenia was levered out of Yugoslavia by Western European capitalism, to be launched into the maelstrom of neo-liberal capitalism. Out of the frying pan into the fire, the Left opposition to the regime is even now haunted by nostalgia for what actually seemed, in retrospect, not so bad after all, for the way things were then. And it is easy to read Žižek’s own scorn for old Stalinist self-management socialism as tinged with regret that things have turned out so badly, and with justifiable rage at how capitalism is now ravaging the whole planet.

The second thing to note about the disintegration of Yugoslavia is that the opposition movement in Slovenia, of which Žižek was a part, even while he was working as a minor functionary in a sub-committee of the party apparatus, was quite distinctive. Different strands of the “dissident” and opposition movement in Eastern Europe were influenced by free-market liberal or socialist ideas, and there were currents of work, including in other parts of Yugoslavia, that drew on Frankfurt School critical theory. The opposition in Slovenia, on the other hand, and this much is already indicated in the title of Žižek’s master’s thesis, was very taken with structuralist theory. Althusser’s (1971) account of the role of “interpellation” of the subject by ideological state apparatuses and Foucault’s (1977) descriptions of disciplinary “self-management” as self-regulation in the service of power seemed ideally suited to what was happening inside Slovenia, and an increasingly popular politics of subversion and “resistance” also drew on the kinds of situationist strategies that accompanied structuralism and so-called “post-structuralism” in France. And then, when things did kick off in the 1970s against the regime, they did so through punk (Simmie and Deklava 1991).

This gives us the conditions of possibility for forms of theory intimately linked to sarcastic and then increasingly open opposition, a politics of ideology-critique that was smart enough not to believe that it spoke in the name of any unmediated authentic reality under the surface. The contradictions in the regime were thus exploded from within, opened up in such a way as to keep them open rather than allow anyone – religious groups, nationalists, old socialists – to close them over again. This contestation of power, in which Žižek was deeply involved as student and as theoretical inspiration, was one which relied on strategies of “overidentification,” internally contradictory and paradoxical disruption of the ideological apparatus which pretended to buy into what it corroded, which ate away at what it seemed to be agreeing to. This is the time of Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), a more slippery and indeterminate form of opposition than the regime could handle, and as lies of the regime were met by more enjoyable and potent truth through avatars of this opposition movement, we could see a necessarily and always divided critique pitted against a cracked but defensive system (Monroe 2005). And we can see in this the battle lines drawn on which Žižek wrote then, a field of conceptual activism that he still speaks from and to now.

Then

This then provides the setting for the articulation of theoretical resources – from Marxism, psychoanalysis, and Hegelian philosophy – that exploits the internal fractures of each, and works those contradictions against each of the other traditions. There had, of course, been attempts to combine Marx and Freud in the Frankfurt School tradition, and this also within a broadly Hegelian framework (Adorno and Horkheimer 1979), but it was evident that a seamless combination of the three currents of work was impossible. Impossibility is the name of the game for Žižek; what Kant and then Foucault referred to as “conditions of possibility” for something to be thought, for a theoretical practice and cultural form, and, more importantly, conditions of impossibility. This is why there is no unity, wholeness, cosmology, or worldview without contradictions that will not at some point explode and change the symbolic coordinates within which we choose and act. Let us take each resource in turn, and notice what Žižek does with it.

First, Marxism that pretended to be a coherent tradition of work was evidently no such thing. Marxism is the theory and practice of class struggle, which in Žižek’s hands becomes the site of a fundamental antagonism in the “symbolic” while also operating as traumatic kernel of the “real” as that which resists and disrupts both the symbolic and “imaginary” understanding of what we each and all are like. Already Žižek indexes this antagonism to the lack of sexual rapport in Lacan’s (1988) Seminar XX. There is no sexual rapport, and for Žižek there is no overarching common interest or point of agreement that transcends the real of class struggle.