Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

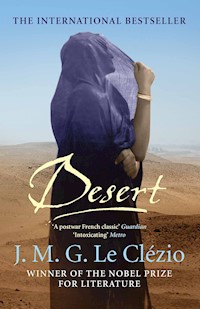

The international bestseller, by the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature 2008, available for the first time in English translation. Young Nour is a North African desert tribesman. It is 1909, and as the First World War looms Nour's tribe - the Blue Men - are forced from their lands by French colonial invaders. Spurred on by thirst, hunger, suffering, they seek guidance from a great spiritual leader. The holy man sends them even further from home, on an epic journey northward, in the hope of finding a land in which they can again be free. Decades later, an orphaned descendant of the Blue Men - a girl called Lalla - is living in a shantytown on the coast of Morocco. Lalla has inherited both the pride and the resilience of her tribe - and she will need them, as she makes a bid to escape her forced marriage to a wealthy older man. She flees to Marseilles, where she experiences both the hardships of immigrant life - as a hotel maid - and the material prosperity of those who succeed - when she becomes a successful model. And yet Lalla does not betray the legacy of her ancestors. In these two narratives set in counterpoint, Nobel Prize-winning novelist J. M. G. Le Clézio tells - powerfully and movingly - the story of the 'last free men' and of Europe's colonial legacy - a story of war and exile and of the endurance of the human spirit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DESERT

J. M. G. Le Clézio was born on 13 April 1940 in Nice and was educated at the University College of Nice and at Bristol and London universities. Since publication of his first novel, Le Procès-verbal (The Interrogation), he has written over forty highly acclaimed books, while his work has been translated into thirty-six languages. He divides his time between France (Nice, Paris and Brittany), New Mexico and Mauritius. In 2008 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

J.M.G. Le Clézio

DESERT

Translated from the French by C. Dickson

Originally published in French in 1980 as Désert by Editions Gallimard, Paris.

First published in English translation in the United States of America in 2009 by Verba Mundi, David R. Godine, PO Box 450, Jaffrey, New Hampshire, 03452.

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airport and export trade paperback in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Editions GALLIMARD, Paris, 1980 Translation copyright © C. Dickson, 2009

The moral right of J. M. G. Le Clézio to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of C. Dickson to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

13579 10 8642

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 381 0

eBook ISBN: 978 1 84887 384 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Happiness

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Life wth the Slaves

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

About the Author

DESERT

Saguiet al-Hamra, winter 1909-1910

THEY APPEARED as if in a dream at the top of the dune, half-hidden in the cloud of sand rising from their steps. Slowly, they made their way down into the valley, following the almost invisible trail. At the head of the caravan were the men, wrapped in their woolen cloaks, their faces masked by the blue veil. Two or three dromedaries walked with them, followed by the goats and sheep that the young boys prodded onward. The women brought up the rear. They were bulky shapes, lumbering under heavy cloaks, and the skin of their arms and foreheads looked even darker in the indigo cloth.

They walked noiselessly in the sand, slowly, not watching where they were going. The wind blew relentlessly, the desert wind, hot in the daytime, cold at night. The sand swirled about them, between the legs of the camels, lashing the faces of the women, who pulled the blue veils down over their eyes. The young children ran about, the babies cried, rolled up in the blue cloth on their mothers’ backs. The camels growled, sneezed. No one knew where the caravan was going.

The sun was still high in the stark sky, sounds and smells were swept away on the wind. Sweat trickled slowly down the faces of the travelers; the dark skin on their cheeks, on their arms and legs was tinted with indigo. The blue tattoos on the women’s foreheads looked like shiny little beetles. Their black eyes, like drops of molten metal, hardly seeing the immense stretch of sand, searched for signs of the trail in the rolling dunes.

There was nothing else on earth, nothing, no one. They were born of the desert, they could follow no other path. They said nothing. Wanted nothing. The wind swept over them, through them, as if there were no one on the dunes. They had been walking since the very crack of dawn without stopping, thirst and weariness hung over them like a lead weight. Their cracked lips and tongues were hard and leathery. Hunger gnawed their insides. They couldn’t have spoken. They had been as mute as the desert for so long, filled with the light of the sun burning down in the middle of the empty sky, and frozen with the night and its still stars.

They continued to make their slow way down the slope toward the valley bottom, zigzagging when loose sand shifted out from under their feet. The men chose where their feet would come down without looking. It was as if they were walking along invisible trails leading them out to the other end of solitude, to the night. Only one of them carried a gun, a flintlock rifle with a long barrel of blackened copper. He carried it on his chest, both arms folded tightly over it, the barrel pointing upward like a flagpole. His brothers walked alongside him, wrapped in their cloaks, bending slightly forward under the weight of their burdens. Beneath their cloaks, the blue clothing was in tatters, torn by thorns, worn by the sand. Behind the weary herd, Nour, the son of the man with the rifle, walked in front of his mother and sisters. His face was dark, sun-scorched, but his eyes shone and the light of his gaze was almost supernatural.

They were the men and the women of the sand, of the wind, of the light, of the night. They had appeared as if in a dream at the top of a dune, as if they were born of the cloudless sky and carried the harshness of space in their limbs. They bore with them hunger, the thirst of bleeding lips, the flintlike silence of the glinting sun, the cold nights, the glow of the Milky Way, the moon; accompanying them were their huge shadows at sunset, the waves of virgin sand over which their splayed feet trod, the inaccessible horizon. More than anything, they bore the light of their gaze shining so brightly in the whites of their eyes.

The herd of grayish-brown goats and sheep walked in front of the children. The beasts also moved forward not knowing where, their hooves following in ancient tracks. The sand whirled between their legs, stuck in their dirty coats. One man led the dromedaries simply with his voice, grumbling and spitting as they did. The hoarse sound of labored breathing caught in the wind, then suddenly disappeared in the hollows of the dunes to the south. But the wind, the dryness, the hunger, no longer mattered. The people and the herd moved slowly down toward the waterless, shadeless valley bottom.

They’d left weeks, months ago, going from one well to another, crossing dried torrents lost in the sands, walking over plateaus, climbing rocky hills. The herd ate stubby grasses, thistles, euphorbia leaves, sharing them with the tribe. In the evening, when the sun was nearing the horizon and the shadows of the bushes grew inordinately long, the people and animals stopped walking. The men unloaded the camels, pitched the large tent of brown wool, standing on its single cedar wood pole. The women lit the fire, prepared the mashed millet, the sour milk, the butter, the dates. Night fell very quickly, the vast cold sky opened out over the dark earth. And then the stars appeared, thousands of stars stopped motionless in space. The man with the rifle who led the group called to Nour and showed him the tip of the Little Dipper, the lone star known as Cabri, and on the other side of the constellation, Kochab, the blue. To the east, he showed Nour the bridge where five stars shone: Alkaïd, Mizar, Alioth, Megrez, Fecda. In the far-eastern corner, barely above the ash-colored horizon, Orion had just appeared with Alnilam, leaning slightly to one side like the mast of a boat. He knew all the stars, he sometimes called them strange names, names that were like the beginning of a story. Then he showed Nour the route they would take the next day, as if the lights blinking on in the sky plotted the course that men must follow on earth. There were so many stars! The desert night was full of those sparks pulsing faintly as the wind came and went like a breath. It was a timeless land, removed from human history perhaps, a land where nothing else could come to be or die, as if it were already beyond other lands, at the pinnacle of earthly existence. The men often watched the stars, the vast white swath that is like a sandy bridge over the earth. They talked a little, smoking rolled kif leaves; they told each other stories of journeys, rumors of the war with the Christians, of reprisals. Then they listened to the night.

The flames of the twig fire danced under the copper teakettle, making a sound of sizzling water. On the other side of the brazier, the women were talking, and one was humming a tune for her baby who was falling asleep at her breast. The wild dogs yelped, and the echoes in the hollows of the dunes answered them, like other wild dogs. The smell of the livestock rose, mingled with the dampness of the gray sand, with the acrid odor of the smoke from the braziers.

Afterward, the women and children went to sleep in the tent, and the men lay down in their cloaks around the cold fire. They melted into the vast stretch of sand and rock – invisible – as the black sky sparkled ever more brilliantly.

They’d been walking like that for months, years maybe. They’d followed the routes of the sky between the waves of sand, the routes coming from the Drâa, from Tamgrout, from the Erg Iguidi, or farther north – the route of the Aït Atta, of the Gheris, coming from Tafilelt, that joins the great ksours in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, or else the endless route that penetrates into the heart of the desert, beyond Hank, in the direction of the great city of Timbuktu. Some died along the way, others were born, were married. Animals died too, throats slit open to fertilize the entrails of the earth, or else stricken with the plague and left to rot on the hard ground.

It was as if there were no names here, as if there were no words. The desert cleansed everything in its wind, wiped everything away. The men had the freedom of the open spaces in their eyes, their skin was like metal. Sunlight blazed everywhere. The ochre, yellow, gray, white sand, the fine sand shifted, showing the direction of the wind. It covered all traces, all bones. It repelled light, drove away water, life, far from a center that no one could recognize. The men knew perfectly well that the desert wanted nothing to do with them: so they walked on without stopping, following the paths that other feet had already traveled in search of something else. As for water, it was in the aiun: the eyes that were the color of the sky, or else in the damp beds of old muddy streams. But it wasn’t water for pleasure or for refreshment either. It was just a sweat mark on the surface of the desert, the meager gift of an arid God, the last shudder of life. Heavy water wrenched from the sand, dead water from crevices, alkaline water that caused colic, vomiting. They must walk even farther, bending slightly forward, in the direction the stars had indicated.

But it was the only – perhaps the last – free land, the

land in which the laws of men no longer mattered. A land for stones and for wind, and for scorpions and jerboas too, creatures who know how to hide and flee when the sun burns down and the night freezes over.

Now they appeared above the valley of Saguiet al- Hamra, slowly descending the sandy slopes. On the floor of the valley, traces of human life began: fields surrounded by drystone walls, pens for camels, shacks made of the leaves of dwarf palms, large woolen tents like upturned boats. The men descended slowly, digging their heels into the sand that crumbled and shifted underfoot. The women slowed their pace and remained far behind the group of animals, suddenly frantic from the smell of the wells. Then the immense valley appeared, spreading out under the plateau of stones. Nour looked for the tall, dark green palms rising from the ground in close rows around the clear freshwater lake; he looked for the white palaces, the minarets, everything he had been told about since his childhood whenever anyone had mentioned the city of Smara. It had been so long since he’d seen trees. His arms hung loosely from his body as he walked down toward the valley bottom, eyes half shut against the sun and the sand.

As the men neared the floor of the valley, the city they had glimpsed briefly disappeared, and they found only dry, barren land. The heat was torrid, sweat streamed down Nour’s face, making his blue clothing stick to his lower back and shoulders.

Now other men, other women also appeared, as if they’d suddenly sprung up from the valley. Some women had lit their braziers for the evening meal, children, men sitting quietly in front of their dusty tents. They’d come from all parts of the desert, beyond the stony Hamada, from the mountains of Cheheïba and Ouarkziz, from Siroua, from the Oum Chakourt Mountains beyond even the great southern oases, from the underground lake of Gourara. They’d come through the mountains at Maïder Pass, near Tarhamant, or lower down where the Drâa joins the Tingut, through Regbat. All of the southern peoples had come, the nomads, the traders, the shepherds, the looters, the beggars. Perhaps some of them had left the Kingdom of Biru or the great oasis of Oualata. Their faces bore the ruthless mark of the sun, of the deathly-cold nights deep in the desert. Some of them were a blackish, almost red color, tall and slender, they spoke an unknown language; they were Tubbus come from across the desert, from Borku and Tibesti, eaters of kola nuts, who were going all the way to the sea.

As the troop of people and livestock approached, the black shapes of humans multiplied. Behind twisted acacias, huts of mud and branches appeared, like so many termite mounds. Houses of adobe, pillboxes of planks and mud, and most of all, those low, drystone walls, barely even knee-high – dividing the red soil into a honeycomb of tiny patches. In fields no larger than a saddle blanket, the harratin slaves tried to raise a few broad beans, peppers, some millet. The irrigation canals extended their parched ditches across the valley to capture the slightest drop of moisture.

They had arrived now in the environs of the great city of Smara. The people, the animals, all moved forward over the desiccate earth, along the bottom of the deep gash of the Saguiet Valley.

They had been waiting for so many hard flintlike days, so many hours, to see this. There was so much suffering in their aching bodies, in their bleeding lips, in their scorched gaze. They hurried toward the wells, impervious to the cries of the animals or the mumbling of the other people. Once they reached the wells and were before the stone wall holding up the soggy earth, they stopped. The children shooed off the animals by throwing stones, while the men knelt down to pray. Then each of them dipped his face in the water and drank deeply.

It was just like that, those eyes of water in the desert. But the tepid water still held the strength of the wind, the sand, and the great frozen night sky. As he drank, Nour could feel the emptiness that had driven him from one well to the next entering him. The murky and stale water nauseated him, did not quench his thirst. It was as if the silence and loneliness of the dunes and the great plateaus were settling deep inside of him. The water in the wells was still, smooth as metal, with bits of leaves and animal wool floating on its surface. At the other well, the women were washing themselves and smoothing their hair.

Near them, the goats and dromedaries stood motionless, as if they were tethered to stakes in the mud around the well.

Other men came and went between the tents. They were blue warriors of the desert, veiled, armed with daggers and long rifles, striding along, not looking at anyone; Sudanese slaves, dressed in rags, carrying loads of millet or dates, goatskins filled with oil; sons of great tents with almost black skin – dressed in white and dark blue – known as Chleuhs; sons of the coast with red hair and freckles on their skin; men of no race, no name; leprous beggars who did not go near the water. All of them were walking over the stone-strewn red dust, making their way toward the walls of the holy city of Smara. They had fled the desert for a few hours, a few days. They had unrolled the heavy cloth of their tents, wrapped themselves in their woolen cloaks, they were awaiting the night. They were eating now, ground millet mixed with sour milk, bread, dried dates that tasted of honey and of pepper. Flies and mosquitoes danced around the children’s heads in the evening air, wasps lit on their hands, their dust-stained cheeks.

They were talking now, very loudly, and the women in the stifling darkness of the tents laughed and threw little pebbles out at the children who were playing. Words gushed from the men’s mouths as if in drunkenness, words that sang, shouted, echoed with guttural sounds. Behind the tents near the walls of Smara, the wind whistled in the branches of the acacias, in the leaves of the dwarf palms. And yet, the men and women whose faces and bodies were tinted blue with indigo and sweat were still steeped in silence; they had not left the desert.

They did not forget. The great silence that swept constantly over the dunes was deep in their bodies, in their entrails. That was the true secret. Every now and again, the man with the rifle stopped talking to Nour and looked back toward the head of the valley, from where the wind was coming.

Sometimes a man from another tribe walked up to the tent and greeted them, extending his two open hands. They exchanged but a few brief words, a few names. But they were words and names that vanished immediately, simply vague traces that the wind and the sand would cover over.

When night fell over the well water there, the starfilled desert sky reigned again. In the valley of Saguiet al- Hamra, nights were milder, and the new moon rose in the dark sky. The bats began their dance around the tents, flitting over the surface of the well water. The light from the braziers flickered, giving off a smell of hot oil and smoke. Some children ran between the tents, letting out barking sounds like dogs. The beasts were already asleep, the dromedaries with their legs hobbled, the sheep and the goats in the circles of drystone.

The men let down their guard. The guide had laid his rifle on the ground at the entrance to the tent and was smoking, gazing out into the night. He was hardly listening to the soft voices and laughter of the women sitting near the braziers. Maybe he was dreaming of other evenings, other journeys, as if the burn of the sun on his skin and the aching thirst in his throat were only the beginning of some other desire.

Sleep drifted slowly over the city of Smara. Down in the south, on the great rocky Hamada, there was no sleep at night. There was the numbing cold, when the wind blew on the sand, laying the base of the mountains bare. It was impossible to sleep on the desert routes. One lived, one died, forever peering out with a steady gaze, eyes burning with weariness and with light. Sometimes the blue men came across a member of their tribe sitting up very straight in the sand, legs stretched out in front, body stock still in the shredded clothing stirring in the wind. In the gray face, the blackened eyes were set on the shifting horizon of dunes, for that is how death had come upon him.

Sleep is like water, no one could truly sleep far from the springs. The wind blew, just like the wind up in the stratosphere, depriving the earth of all warmth.

But there in the red valley the travelers could sleep.

The guide awoke before the others, he stood very still in front of the tent. He watched the haze moving slowly up the valley toward the Hamada. Night faded with the passing haze. Arms crossed on his chest, the guide was barely breathing, his eyelids did not move. He was waiting for the first light of dawn, the fijar, the white patch that is born in the east, above the hills. When the light appeared, he bent over Nour and woke him gently, putting a hand on his shoulder. Together they walked away in silence; they walked along the sandy trail that led to the wells. Dogs barked in the distance. In the gray dawn light, the man and Nour washed themselves according to the ritual, one part after another, starting over again three times. The well water was cold and pure, water born of the sand and of the night. The man and the boy washed their faces and their hands once more, then they turned toward the east for the first prayer. The sky was just beginning to light the horizon.

In the campsites, the braziers glowed in the last shadows. The women went to draw water; the little girls ran through the water shouting a little, then they came teetering back with the jars balanced on their thin necks.

The sounds of human life began to rise from the campsites and the mud houses: sounds of metal, of stone, of water. The yellow dogs gathered in the square, circling each other and yapping. The camels and the herds pawed the ground, raising the red dust.

The light on the Saguiet al-Hamra was beautiful at that moment. It came from the sky and the earth at once, a golden and copper light that shimmered in the blank sky, without burning or blinding. The young girls, drawing back a flap of the tent, combed their heavy manes of hair, picking out lice, tying up their buns and attaching their blue veils to them. The lovely light shone on their copper faces and arms.

Squatting very still in the sand, Nour was also watching the light filling the sky over the campsites. Flights of partridges passed slowly through the air, making their way up the red valley. Where were they going? Maybe they would go all the way up to the head of the Saguiet, all the way to the narrow valleys of red earth between the Agmar Mountains. Then when the sun went down, they’d come back toward the open valley, over the fields where human houses look like termite houses.

Perhaps they had already seen Aaiún, the town of mud and planks where the roofs are sometimes made of red metal; perhaps they had even seen the emerald and bronze-colored sea, the free and open sea?

Travelers began arriving in the Saguiet al-Hamra, caravans of people and animals coming down the dunes raising clouds of red dust. They went past the campsites without even turning their heads, still distant and lonely as if they were in the middle of the desert.

They walked slowly toward the water in the wells, to soothe their bleeding mouths. The wind had begun to blow up on the Hamada. Down in the valley it lost momentum in the dwarf palms, the thorn bushes, the labyrinths of drystone. Still, the world far from the Saguiet glittered in the travelers’ eyes; plains of razor- sharp rocks, jagged mountains, crevasses, blankets of sand glinting blindingly in the sunlight. The sky was boundless, of such a harsh blue that it burnt the face. Still farther out, men walked through the maze of dunes, in a foreign world.

But it was their true world. The sand, the stones, the sky, the sun, the silence, the suffering, not the metal and cement towns with the sounds of fountains and human voices. It was here – in the barren order of the desert – where everything was possible, where one walked shadowless on the edge of his own death. The blue men moved along the invisible trail toward Smara, freer than any creature in the world could be. All around, as far as the eye could see, were the shifting crests of dunes, the waves of wide open spaces that no one could know. The bare feet of the women and children touched the sand, leaving light prints that the wind erased immediately. In the distance, mirages floated, suspended between the earth and the sky, white cities, fairs, caravans of camels and donkeys loaded with provisions, busy dreams. And the men themselves were like mirages, born unto the desert earth in hunger, thirst, and weariness.

The routes were circular, they always led back to the point of departure, winding in smaller and smaller circles around the Saguiet al-Hamra. But it was a route that had no end, for it was longer than human life.

The people came from the east, beyond the Aadme Rieh Mountains, beyond Yetti, Tabelbala. Others came from the south, from the al-Haricha oasis, from the Abd al-Malek well. They walked westward, northward till they reached the shores of the sea, or else through the great salt mines of Teghaza. They had come back to the holy land, the valley of Saguiet al-Hamra, loaded with food and ammunition, not knowing where they would go next. They traveled by watching the paths of the stars, fleeing the sandstorms when the sky turns red and the dunes begin to move.

That is how the men and women lived, walking, finding no rest. One day they died, taken by surprise in the sharp sunlight, hit by an enemy bullet, or else consumed with fever. Women gave birth to children, simply squatting in the shade of a tent, held up by two other women, their bellies bound with wide cloth belts. From the first minute of their lives, the men belonged to the boundless open spaces, to the sand, to the thistles, the snakes, the rats, and especially to the wind, for that was their true family. The little girls with copper hair grew up, learned the endless motions of life. They had no mirror other than the fascinating stretches of gypsum plains under the pure blue sky. The boys learned to walk, talk, hunt, and fight simply to learn how to die on the sand.

* * *

Standing in front of the tent on the men’s side, the guide remained still for a long time, watching the caravans moving toward the dunes, toward the wells. The sun shone on his brown face, his aquiline nose, his long, curly, copper-colored hair. Nour had spoken to him, but he wasn’t listening. Then when the camp had calmed down, he motioned to Nour and together they walked away along the trail leading north, toward the center of the Saguiet al-Hamra. At times they encountered someone walking toward Smara, and they exchanged a few words.

“Who are you?”

“Bou Sba. And you?”

“Yuemaïa.”

“Where are you from?”

“Aaïn Rag.”

“I’m from the South, from Iguetti.”

Then they separated without saying goodbye. Farther along, the almost invisible trail led through the rocks and straggly stands of acacia. Walking was difficult due to the sharp stones jutting up from the red earth, and Nour had a hard time following his father. The light was brighter, the desert wind blew the dust up under their feet. The valley wasn’t wide there, it was a sort of gray and red crevasse that gleamed like metal in places. Stones cluttered the dry bed of the torrent, white and red stones, black flints glinting in the sun.

The guide walked with his back to the sun, bent forward, his head covered with his woolen cloak. The thorns on the bushes tore at Nour’s clothing, lashed his naked legs and feet, but he paid no attention. His eyes were fixed straight ahead on the shape of his hasting father. All of a sudden, they both stopped: the white tomb had appeared between the stony hills, shining in the light from the sky. The man stood still, bowing slightly as if greeting the tomb. Then they started walking again on the stones that rolled underfoot.

Slowly, without turning his eyes away, the guide climbed up to the tomb. As they drew nearer, the domed roof seemed to rise out of the red rocks, grow skyward. The lovely pure light illuminated the tomb, inflated it in the furnace-hot air. There was no shade in that place, only the sharp stones of the hill, and beneath, the dry bed of the torrent.

They came up in front of the tomb. It was just four whitewashed walls set on a foundation of red stones. There was only one door, like the opening to an oven, obstructed by a huge red rock. Above the walls, the white dome was shaped like an eggshell and ended in a spearhead. Now Nour saw nothing but the entrance to the tomb, and the door grew larger in his eyes, becoming the door to an immense monument with walls like cliffs of chalk, with a dome as high as a mountain. Here, the desert wind and heat, the loneliness of day stopped: here, the faint trails ended, even those where lost people walk, mad people, vanquished people. Perhaps it was the center of the desert, the place where everything had begun long ago, when people had come here for the very first time. The tomb shone out on the slope of the red hill. The sunlight bounced off the tamped earth, burned down on the white dome, caused small trickles of red powder to sift down along the cracks in the walls from time to time. Nour and his father were alone next to the tomb. A heavy silence hung over the valley of the Saguiet al-Hamra.

From the round door, as he tipped the large rock away, the guide saw the powerful cold shadows and it seemed to him that he felt a sort of breath on his face.

Around the tomb was an area of red earth, tamped with the feet of visitors. That is where the guide and Nour stopped first – to pray. Up there on top of the hill, near the tomb of the holy man, with the valley of the Saguiet al-Hamra stretching its dry streambed into the distance and the vast horizon upon which other hills, other rocks appeared against the blue sky, the silence was even more striking. It was as if the world had stopped moving and talking, had turned to stone.

From time to time, Nour could nevertheless hear the cracking of the mud walls, the buzzing of an insect, the wailing of the wind.

“I have come,” said the man kneeling on the tamped earth. “Help me, spirit of my grandfather. I have crossed the desert, I have come to ask for your blessing before I die. Help me, give me your blessing, for I am of your own flesh. I have come.”

That is the way he spoke, and Nour listened to his father’s words without understanding. He spoke, sometimes in a full voice, sometimes in a low murmuring singsong, swaying his head, constantly repeating those simple words, “I have come, I have come.”

He leaned down, took up some red dust in the hollow of his hands and let it run over his face, over his forehead, his eyelids, his lips.

Then he stood up and walked to the door. In front of the opening, he knelt down and prayed again, his forehead touching the stone on the threshold. Slowly, the darkness inside of the tomb dissipated, like a night fog. The walls of the tomb were bare and white, the same as on the outside, and the low ceiling displayed its framework of branches mixed with mud.

Nour went in now too, on all fours. He felt the hard cold floor of earth mixed with sheep’s blood under his hands. The guide was lying on his stomach at the back of the tomb on the mud floor. Palms on the ground, arms stretched out before him, melting in with the earth. Now he was no longer praying, no longer singing. He was breathing slowly, his mouth against the ground, listening to the blood beating in his throat and ears. It was as if something unknown were entering him, through his mouth, through his forehead, through the palms of his hands, and through his stomach, something that went very deep inside of him and changed him imperceptibly. Perhaps it was the silence that had come from the desert, from the sea of dunes, from the rock-filled mountains in the moonlight, or from the great plains of pink sand where the sunlight dances and wavers like a curtain of rain, the silence of the green waterholes, looking up at the sky like eyes, the silence of the cloudless, birdless sky where the wind runs free.

The man lying on the ground felt his limbs growing numb. Darkness filled his eyes, as it does before one drifts into sleep. Yet at the same time new strength came to him through his stomach, through his hands, creeping into each of his muscles. Everything inside of him was changing, being fulfilled. There was no more suffering, no more desire, no more revenge. He forgot all of that, as if the water of the prayer had washed his mind clean. There were no more words either, the cold darkness in the tomb made them pointless. Instead there was this strange current pulsing in the earth mixed with blood, this vibration, this warmth. There wasn’t anything like it on earth. It was a direct force, without thought, that came from the depths of the earth and went out into the depths of space, as if an invisible bond united the body of the man lying there and the rest of the world.

Nour was barely breathing, watching his father in the dark tomb. His fingers were spread out on the cold earth which was pulling him through space on a dizzying course.

They remained like that for a long time, the guide lying on the ground and Nour crouching, eyes wide, staying very still. Then when it was all over, the man rose slowly and helped his son out. He went to sit down against the wall of the tomb. He seemed exhausted, as if he had walked for hours without eating or drinking. But there was a new strength deep within him, a joyfulness that lit his eyes. Now it was as if he knew what he needed to do, as if he knew in advance the path he must follow.

He pulled the flap of his woolen cloak down over his face, and he thanked the holy man without uttering a word, simply moving his head a little and humming in his throat. His long blue hands stroked the tamped earth, closed over a handful of fine dust.

Before them, the sun followed the curve of the sky, slowly descending on the other side of the Saguiet al- Hamra. The shadows of the hills and rocks grew long in the valley bottom. But the guide didn’t seem to notice. Sitting very still, his back leaning against the wall of the tomb, he had no sense of the passing day, or hunger, or thirst. He was filled with a different force, from a different time that had made him a stranger to the order of man. Perhaps he was no longer waiting for anything, no longer knew anything, and now he resembled the desert – silence, stillness, absence.

When night began to fall, Nour was frightened and he touched his father’s shoulder. The man looked at him in silence, with a slight smile on his face. Together they started down the hill toward the dry torrent. Despite the gathering night, their eyes stung and the hot wind burned their faces and hands. The man staggered a little as he walked on the path, and he needed to lean on Nour’s shoulder.

Down at the bottom of the valley, the water in the wells was black. Mosquitoes hung in the air, trying to get at the children’s eyelids. Farther on, near the red walls of Smara, bats skimmed over the tents, circled around the braziers. When they reached the first well, Nour and his father stopped again to carefully wash each part of their bodies. Then they said the last prayer, turning toward the approaching night.

THEN GREATER and greater numbers of them came to the valley of the Saguiet al-Hamra. They came from the south, some with their camels and horses, but most of them on foot, because the animals died of thirst and disease along the way. Every day the young boy saw new campsites around the mud ramparts of Smara. The brown woolen tents made new circles around the walls of the city. Every evening at nightfall, Nour watched the travelers arriving in clouds of dust. Never had he seen so many human beings. There was a constant commotion of men’s and women’s voices, of children’s shrill shouts, the weeping of infants mingled with the bleating of goats and sheep, with the clattering of gear, with the grumbling of camels. A strange smell that Nour wasn’t really familiar with drifted up from the sand and floated over in short wafts on the evening wind; it was a powerful smell, both acrid and sweet at the same time, the odor of human skin, of breathing, of sweat. The fires burning charcoal, bits of straw, and manure were being lit in the twilight. The smoke from the braziers rose up over the tents. Nour could hear the soft voices of women singing their babies to sleep.

Most of those who were arriving now were old people, women and children, exhausted from their forced march through the desert, clothing torn, feet bare or tied with rags. Their faces were black, burnt with the light, eyes like two pieces of coal. The young children went naked, wounds marking their legs, bellies bloated with hunger and thirst.

Nour wandered through the camp, weaving his way through the tents. He was astonished to see so many people, and at the same time he felt a sort of anxiety because, without really knowing why, he thought that many of those men, those women, those children would soon die.

He was constantly running into new travelers walking slowly down the aisles between the tents. Some of them, black like the Sudanese, came from farther south and spoke a language that Nour didn’t understand. Most of the men’s faces were hidden, wrapped in woolen cloaks and blue cloth; their feet were shod with sandals made of goat leather. They carried long, flintlock rifles with copper barrels, spears, daggers. Nour stepped aside to let them pass, and he watched them walk toward the gate to Smara. They were going to greet the great sheik, Moulay Ahmed ben Mohammed al-Fadel, who was called Ma al- Aïnine, Water of the Eyes.

They all went and sat down on the small benches of dried mud that circled the courtyard in front of the sheik’s house. Then they went to say their prayer at sunset to the east of the well, kneeling in the sand, turning their bodies in the direction of the desert.

When night had come, Nour went back toward his father’s tent and sat down beside his older brother. On the right side of the tent his mother and sisters were talking, stretched out on the carpets between the provisions and the camel’s packsaddle. Little by little, Smara and the valley fell silent again; the sounds of human voices and animal cries faded out one after the other. The magnificently round white disk of the full moon appeared in the black sky. Despite all the heat of day accumulated in the sand, the night was cold. A few bats flew across the moon, dove suddenly toward the ground. Nour, lying on his side with his head resting against his arm, was watching them as he was waiting to doze off. He fell abruptly to sleep, without realizing it, eyes wide open.

When he awoke he had the odd impression that time had stood still. He looked around for the disk of the moon and upon seeing that it had begun its descent to the west, he realized he had slept for a long time.

The silence hanging over the campsites was oppressive. All that could be heard was the distant howling of wild dogs somewhere out on the edge of the desert.

Nour got up and saw that his father and brother were no longer in the tent. He could only make out the vague shapes of the women and children rolled up in the carpets on the left side of the tent. Nour started walking along the sandy path between the campsites toward the ramparts of Smara. The moonlit sand was very white against the blue shadows of stones and bushes. There was not a single sound, as if all the men were asleep, but Nour knew that the men weren’t in the tents. Only the children were sleeping, and the women were lying very still, rolled up in their cloaks and carpets, looking out of the tents. The night air made the young boy shiver, and the sand was cold and hard under his bare feet.

When he neared the city walls, Nour could hear the murmuring of men’s voices. A little farther on, he saw the motionless shape of a guard squatting in front of the gate to the city, his long rifle propped against his knees. But Nour knew of a place where the mud rampart had collapsed, and he was able to enter Smara without going past the sentinel.

He immediately discovered the men assembled in the courtyard of the sheik’s house. They were sitting in groups of five or six on the ground around braziers where large copper kettles held water for making green tea. Nour slipped silently into the gathering. No one looked at him. All the men were watching a group of warriors standing in front of the door to the house. There were a few soldiers from the desert, dressed in blue, standing absolutely still, staring at an old man dressed in a simple cloak of white wool that was pulled up over his head, and two armed young men who took turns speaking out vehemently.

From where Nour was seated, it was impossible to understand their words, due to the sounds of the men who were repeating or commenting on what had already been said. When his eyes had adjusted to the contrast of the darkness and the red glow of the braziers, Nour recognized the figure of the old man. It was the great sheik Ma al-Aïnine, the man he’d already caught a glimpse of when his father and older brother came to pay their respects after their arrival at the well in Smara.

Nour asked the man next to him who the young men beside the sheik were. He was told their names: “Saadbou and Larhdaf, the brothers of Ahmed al-Dehiba, he who is called Particle of Gold, he who will soon be our true king.”

Nour didn’t try to hear the words of the two young warriors. All of his attention was focused on the frail form of the old man standing motionless between them, with the moon lighting his cloak and making a very white patch.

All the men were looking at him too, as if with the same set of eyes, as if he were the one really speaking, as if he would make a single gesture and everything would suddenly be transformed, for the very order of the desert emanated from him.

Ma al-Aïnine did not move. He didn’t seem to hear the words of his sons, or the endless murmur coming from the hundreds of men sitting in the courtyard before him. At times he would cock his head slightly, look out over the men and the mud walls of his city toward the dark sky, in the direction of the rocky hills.

Nour thought that perhaps he simply wanted the men to return to the desert, from where they had come, and his heart sank. He didn’t understand the words of all the men around him. Above Smara the sky was unfathomable, frozen, its stars dimmed in the white haze of moonlight. And it was a bit like a sign of death, or abandonment, like a sign of the terrible absence that was hollowing out the tents that stood so still near the city walls. Nour felt this even more strongly when he looked at the fragile shape of the great sheik, it was as if he were entering into the very heart of the old man, entering his silence.

Other sheiks, chieftains of great tents, and Tuareg warriors came to join the group one after another. They all spoke the same words, their voices cracking from fatigue and from thirst. They spoke of the soldiers of the Christians who made incursions into the southern oases bringing war to the nomads; they spoke of fortified towns the Christians were building in the desert barring access to wells all the way to the seashore. They spoke of lost battles, of the men who had died, so many of them that their names could no longer be remembered, of swarms of women and children fleeing northward through the desert, of the carcasses of dead livestock strewn everywhere along the way. They spoke of caravans that were cut short when the soldiers of the Christians liberated the slaves and sent them back to the south, and how the Tuareg warriors received money from the Christians for each slave they had stolen from the convoys. They spoke of merchandise and livestock being seized, of bands of brigands that had forayed into the desert along with the Christians. They spoke also of troops of soldiers marching for the Christians, guided by the black men from the south, so numerous that they covered the sand dunes from one end of the horizon to the other. And the horsemen who encircled the camps and killed anyone who resisted them on the spot, and then took the children away to put them into Christian schools in the forts on the coast. So when the other men heard this, they said it was true, by God, and the clamor of voices swelled up and heaved in the square like the sound of a rising wind.

Nour listened to the clamoring of voices growing louder, then subsiding, like the passage of the desert wind over the dunes, and there was a knot in his throat because he knew a terrible danger was threatening the city and all the men, a danger he was unable to understand.

Now, almost without blinking, he was watching the white shape of the old man standing very still between his sons in spite of the weariness and the cold night air. Nour thought that he alone, Ma al-Aïnine, could change the course of this night, calm the anger of the crowd with a wave of his hand or, on the contrary, unleash it with just a few words that would be passed from mouth to mouth and make the wave of rage and bitterness seethe. Like Nour, all the men were looking at him, eyes bright with fatigue and fever, minds tense with suffering. They could all feel their skin, leathered from the burning sun, their lips, blistered from the desert wind. They waited, almost without moving, eyes fixed, searching for a sign. But Ma al-Aïnine didn’t seem to notice them. In his eyes there was a steady remote look as he gazed out over the men’s heads, out beyond the dried mud walls of Smara. Maybe he was looking for the answer to the men’s anxiety in the depths of the nocturnal sky, in the strange blur of light swimming around the disk of the moon. Nour looked up at the place where he could usually see the seven stars of the Little Dipper, but he saw nothing. Only the planet Jupiter was visible, frozen in the icy sky. The haze of moonlight had covered everything. Nour loved the stars, for his father had taught him their names ever since he was a baby; but on this night, it was as if he couldn’t recognize the sky. Everything was immense and cold, engulfed in the white light of the moon, blinded. Down on earth, the fires in the braziers made red holes that lit up the men’s faces oddly. Maybe it was fear that had changed everything, that had emaciated the faces and hands and filled the empty eye sockets with inky shadows; it was night that had frozen the light in the men’s eyes, that had dug out the immense hole in the depths of the sky.

When all the men had finished speaking, each standing up beside Sheik Ma al-Aïnine in turn – all the men whose names Nour had heard his father utter in the past, chieftains of warrior tribes, the men of the legend, the Maqil, the Arib, Oulad Yahia, Oulad Delim, Aroussiyine, Icherguiguine, the Reguibat whose faces were veiled in black, and those who spoke the Chleuh languages, the Idaou Belal, Idaou Meribat, Aït ba Amrane, and even those whose names were not familiar, come from the far side of Mauritania, from Timbuktu, those who had not wanted to sit near the braziers, but who had remained standing near the entrance to the courtyard, wrapped in their cloaks, looking at once guarded and contemptuous, those who hadn’t wanted to speak – Nour observed each of them, one after the other, and he could feel a terrible emptiness hollowing out their faces, as if they would soon die.

Ma al-Aïnine didn’t see them. He hadn’t looked at anyone, except maybe once when his eyes had fallen briefly on Nour’s face, as if he were surprised to see him amidst so many men. Since that barely perceptible moment – quick as a flash in a mirror, even though Nour’s heart had begun beating faster and harder – Nour had been waiting for the sign that the old sheik was to give to the men grouped together before him. The old man stood still, as if he were thinking about something else, while his two sons, leaning toward him, spoke in hushed tones. At last he took out his ebony beads and squatted down very slowly in the dust, head bowed. Then he began to recite the prayer he had written for himself, while his sons sat down on either side of him. Soon afterward, as if that simple act had sufficed, the muttering of voices ceased and silence fell over the square, a cold and heavy silence in the overly white light of the full moon. Distant, barely perceptible sounds from the desert, from the wind, from the dry stones on the plateaus began to fill up the space again. Without saying goodbye, without a word, without making a sound, the men stood up, one after another, and left the square. They walked along the dusty path, one by one, because they didn’t feel like talking to one another anymore. When his father touched his shoulder, Nour got up and also walked away. Before leaving the square, he turned back to look at the strange, frail figure of the old man, all alone now in the moonlight, chanting his prayer with the top part of his body rocking back and forth like someone on horseback.

In the following days anxiety began to mount again in the Smara camp. It was incomprehensible, but everyone could feel it, like a pain in the heart, like a threat. The sun burned down hard during the day, bouncing its brutal light off the edges of rocks and the dried beds of torrents. The foothills of the rocky Hamada shimmered in the distance, and there were always mirages over the Saguiet Valley. New bands of nomads arrived each hour of the day, haggard with weariness and thirst, coming in forced marches from the south, and their silhouettes melted into the horizon along with the scintillating mirages. They walked slowly, feet bandaged with strips of goatskin, carrying their meagre loads on their backs. Sometimes they were followed by half-starved camels and limping horses, goats, sheep. They set up their tents hastily on the edge of the camp. No one went to greet them or ask them where they came from. Some bore the marks of wounds from battles they had fought against the soldiers of the Christians or the looters in the desert; most were on the verge of collapse, spent from fevers and stomach ailments. Sometimes all that was left of an army arrived, decimated, bereft of a leader, womanless, black-skinned men, almost naked in their ragged garments, their glassy eyes bright with fever and folly. They went to drink at the spring in front of the gate to Smara, then they lay down on the ground in the shade of the city walls, as if to sleep, but their eyes remained wide open.

Since the night of the tribal assembly, Nour hadn’t seen Ma al-Aïnine or his sons again. But he distinctly felt that the great clamor of discontent that had been assuaged when the sheik had begun his prayer had not really stopped. It was no longer a matter of words, now. His father, his older brother, his mother said nothing, and they turned their heads away as if they didn’t want to be asked any questions. But the anxiety was still mounting, in the sounds of the camp, in the bleating of the livestock that were growing impatient, in the sound of the footsteps of newcomers arriving from the south, in the harsh words that men spit out at one another or at their children. Anxiety was also present in the sharp odors of sweat, of urine, of hunger – so much acridity seeping up from the ground and from the hidden recesses of the camp. It mounted as food became scarcer, a few pepper dates, sour milk, and oatmeal to be swallowed hastily at the crack of dawn, when the sun had not yet risen from the dunes. Anxiety was in the murky water of the well that the tramping of humans and beasts had disturbed and that green tea could not improve. Sugar had been rare for a long time, and honey too, and the dates were as dry as rocks, and the tough pungent meat came from camels that had died of exhaustion. Anxiety was rising in the dry mouths and bloody fingers, in the weight that bore down on the heads and shoulders of the men, in the heat of day, and then in the cold of night, making children shiver in the folds of worn carpets.

Each day as he walked past the campsites, Nour heard the sound of women crying because someone had died in the night. Each day people edged a little further into despair and anger, and Nour felt his throat growing tighter. He thought of the sheik’s distant gaze drifting out over the invisible hills in the night, then coming to rest on him for a brief moment, like a flash in a mirror that lit him up inside.

All of them had come to Smara from so far away, as if it would be the end of their journey. As if nothing else could be lacking. They had come because there was a lack of land under their feet, as if it had crumbled away behind them, and now it was no longer possible to turn back. And now they were here, hundreds, thousands of them, on land that could not provide for them, land without water, without trees, without food. Their eyes endlessly scoured every point in the circle of the horizon, the jagged mountains to the south, the desert to the east, the dry streambeds of the Saguiet, the high plateaus to the north. Their eyes were also lost in the empty cloudless sky, in which the blaze of the sun was blinding. Then anxiety turned to fear, and fear to anger, and Nour felt a strange ripple pass over the camp, an odor perhaps that rose from the tent tops and circled around the city of Smara. It was also a light-headed feeling, the dizzy feeling of emptiness and hunger that transformed the shapes and colors of the earth, that changed the blue of the sky, that generated great lakes of fresh water in the scorching bottoms of the salinas, that brought the sky to life with clouds of birds and flies.

Nour would go and sit in the shade of the mud wall when the sun was going down and watch the spot where Ma al-Aïnine had appeared that night in the square, the invisible spot where he had squatted down to pray. Sometimes other men would come, as he did, and stand motionless at the entrance to the square to see the wall of red earth with narrow windows. They said nothing, they just looked. Then they went back to their campsites.

Then, after all those days of anger and fear on the earth and in the sky, after all those freezing nights in which one slept very little and awoke suddenly for no particular reason, eyes feverish, body soaked with rank sweat, after all that time, the long days that slowly killed off elderly people and infants, suddenly, without anyone knowing why, the people knew that the time to depart had come.

Nour heard about it even before his mother mentioned anything, even before his brother laughed and said, as if everything had changed, “We’re leaving tomorrow, or day after tomorrow – now listen, we’ll be heading north, that’s what Sheik Ma al-Aïnine said, we’re going far away from here!” Maybe the news had come in the air, or in the dust, or else maybe Nour had heard it as he was gazing at the tamped earth in the square in Smara.