Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

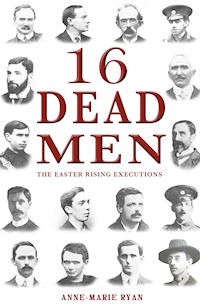

Sixteen men were executed in the aftermath of the Easter Rising in Ireland, 1916: fifteen were shot and one was hanged. Their deaths changed the course of Irish history. But who were these leaders who set in motion events that would lead to the creation of an independent Ireland? The executed leaders of the Easter Rising were a diverse group. This book contains fascinating accounts of the life stories of these men and recounts the events that brought each of them to rebellion in April 1916.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 285

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my parents, Kevin and Mary Ryan

Sixteen Dead Men

O but we talked at large before

The sixteen men were shot,

But who can talk of give and take,

What should be and what not

While those dead men are loitering there

To stir the boiling pot?

You say that we should still the land

Till Germany’s overcome;

But who is there to argue that

Now Pearse is deaf and dumb?

And is their logic to outweigh

MacDonagh’s bony thumb?

How could you dream they’d listen

That have an ear alone

For those new comrades they have found,

Lord Edward and Wolfe Tone,

Or meddle with our give and take

That converse bone to bone?

W. B. Yeats

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Anne-Marie Ryan, 2014

ISBN: 978 1 78117 134 9

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 306 0

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 307 7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Contents

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Patrick Pearse

Thomas Clarke

Thomas MacDonagh

Edward Daly

William Pearse

Michael O’Hanrahan

Joseph Plunkett

John MacBride

Seán Heuston

Michael Mallin

Éamonn Ceannt

Con Colbert

Thomas Kent

Seán Mac Diarmada

James Connolly

Roger Casement

Endnotes

Bibliography

Abbreviations

AOH Ancient Order of Hibernians

BMH Bureau of Military History

CYMS Catholic Young Men’s Society

DMP Dublin Metropolitan Police

GAA Gaelic Athletic Association

GPO General Post Office

GSWR Great Southern and Western Railway

ICA Irish Citizen Army

ILP Independent Labour Party of Ireland

IRA Irish Republican Army

IRB Irish Republican Brotherhood

ISRP Irish Socialist Republican Party

ITGWU Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the support of a number of individuals and institutions while researching and writing this book.

The staff of the reading room at the National Library of Ireland went out of their way on many occasions to locate material. I am also grateful to the staff of the libraries of University College Dublin and Trinity College Dublin. The Trojan work of the staff of the Military Archives in digitising the witness statements collected by the Bureau of Military History between 1947 and 1957 has been of enormous assistance in preparing this book.

I would like to thank the staff at Mercier Press, in particular Mary Feehan and Wendy Logue, for their assistance and encouragement throughout the production of this book. I would also like to thank Robert Doran for his work on proofreading the text.

I acknowledge the support of my former colleagues at Kilmainham Gaol Museum, who over the years have been a source of information, debate and inspiration. I am grateful for the assistance of Niall Bergin, who provided images from the Kilmainham Gaol collection for this book. I would like to give particular thanks to Brian Crowley, curator of the Pearse Museum, for the mentoring, advice and help he gave me throughout my time working for the Office of Public Works.

This book would not have been possible without the patience and encouragement of my family and friends, too numerous to mention here by name.

I owe an eternal debt of gratitude to my parents, Kevin and Mary Ryan, to whom this book is dedicated.

Introduction

The ‘Sixteen Dead Men’ about whom Yeats wrote his poem in the aftermath of the Easter Rising were a diverse group. Ranging in age from twenty-five to fifty-eight, their occupations included headmaster, tobacconist, poet, railway clerk, university lecturer, printer, humanitarian, water bailiff, art teacher, silk weaver, corporation clerk, farmer, trade union leader, bookkeeper, chemist’s clerk and newspaper manager. Two of the leaders were born outside Ireland: Thomas Clarke in the unlikely location of a British Army barracks on the Isle of Wight, James Connolly in the Irish ghetto of Edinburgh. Some had complicated national and religious identities: Patrick and Willie Pearse were the sons of an English stone carver, Thomas MacDonagh’s mother was the daughter of English parents, Roger Casement was raised a Protestant but secretly baptised a Catholic by his mother, and John MacBride was the son of an Ulster-Scots Protestant from Co. Antrim. Others had close links with the institutions of British imperialism that they would later fight against: Michael Mallin and James Connolly were former soldiers in the British Army, Éamonn Ceannt was the son of a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) constable and Roger Casement had been knighted for his services as a British consul exposing the dark side of the rubber trade in the Congo and Peru.

This group of men, who participated in an armed rebellion against British rule in Ireland in April 1916, came to the point of insurrection by a variety of pathways. For many of them, their revolutionary instinct had developed at a young age. Thomas Kent was in his early twenties when he was imprisoned for his activities with the Land League in Co. Cork in the late nineteenth century, Michael O’Hanrahan grew up hearing stories of his ancestors’ involvement in the 1798 rebellion in Co. Wexford, Edward Daly was born into a Limerick family prominent in the Fenian movement, Con Colbert and Seán Heuston were members of the nationalist youth organisation Na Fianna Éireann, and Seán Mac Diarmada’s republican politics were nurtured by his national schoolteacher, who provided him with books on Irish history.

For some, the declaration of an Irish Republic on 24 April 1916 was the culmination of a lifetime’s struggle. Thomas Clarke had become active in the secret revolutionary organisation the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) as a young man and had served fifteen years’ imprisonment for his involvement in the preparations for a Fenian bombing campaign in Britain; James Connolly had devoted his adult life to improving conditions for working-class people in Scotland, Ireland and America, and was a long-standing advocate of the establishment of a socialist Irish republic. But for others, the conversion to radical nationalism came late. Patrick Pearse was a speaker at a pro-Home Rule rally as late as March 1912, Éamonn Ceannt’s nationalist activities were mostly confined to the Irish language movement until he was elected to the Provisional Committee of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913, while Thomas MacDonagh was not co-opted onto the Supreme Council of the IRB until shortly before the Easter Rising.

Seven of the executed leaders of the rebellion sealed their fate by signing the Proclamation of the Irish Republic shortly before the outbreak of the Rising. The document, which declared ‘the right of the Irish people to the ownership of Ireland’ and which guaranteed ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens’, was read aloud by Patrick Pearse outside the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) shortly after noon on Easter Monday. Pearse was president of the provisional government and commander-in-chief of the army of the Irish Republic. He was accompanied by Thomas Clarke, the mastermind of the rebellion, who was invited to be the first signatory of the Proclamation in deference to his contribution to the Fenian movement since the late 1870s. Also present was James Connolly, a fellow signatory and commandant-general of the forces of the Irish Republic in Dublin. Two other signatories were also stationed in the GPO, the headquarters of the rebel forces: Joseph Plunkett, the military strategist of the rebellion, who was dying from tuberculosis, and Seán Mac Diarmada, Clarke’s right-hand man, whose involvement in the action was restricted by lameness in his right leg caused by a bout of polio. The remaining two signatories were in command of outposts in the south-west of Dublin city. Thomas MacDonagh, commandant of the 2nd Battalion, Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers, saw relatively little action at his position at Jacob’s biscuit factory on Bishop Street. By contrast, Éamonn Ceannt, commandant of the 4th Battalion, was involved in intense fighting during Easter Week at the South Dublin Union, a workhouse and hospital complex in the Rialto area of the city.

For the other executed men, the extent of their involvement in the planning of the uprising and their participation in it varied greatly. Edward Daly, like MacDonagh and Ceannt, held the position of commandant of a Volunteer battalion, but he did not learn of the plans for the Easter Rising until the Wednesday before it was due to take place. His rank as commandant of the 1st Battalion, positioned in the area surrounding the Four Courts, ensured that his death sentence was carried out. Likewise Michael Mallin, who held the rank of commandant in Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army (ICA), faced the firing squad for his role in leading the rebel forces who seized the Royal College of Surgeons on St Stephen’s Green during Easter Week.

John MacBride was a veteran Fenian, but his alcoholism and humiliating divorce from Maud Gonne made him an outcast in republican circles and he was not involved in the planning of the Rising. His chance encounter with Irish Volunteers as they assembled at St Stephen’s Green on Easter Monday, while he was on his way to his brother’s wedding, led to his appointment by Thomas MacDonagh as second-in-command at Jacob’s. MacBride’s accidental participation in the rebellion, along with the British authorities’ longstanding resentment of his organisation of the Irish Brigade that fought against the British during the Boer War in South Africa, led to his execution in the Stonebreakers’ Yard of Kilmainham Gaol. Michael O’Hanrahan, who fought alongside MacBride in Jacob’s, held only the rank of quartermaster of the 2nd Battalion. His execution may have owed much to the fact that he was known to the police as a clerk working in the offices of the Irish Volunteers, but it is equally likely that it was due to the fact he was sentenced to death early on in the period of executions, before the tide of public opinion turned against the authorities. Similarly Con Colbert and Seán Heuston – who commanded smaller outposts at Jameson’s Distillery in Marrowbone Lane and the Mendicity Institution – were both executed on 8 May 1916, three days before John Dillon addressed the House of Commons and accused the British authorities of ‘letting loose a river of blood’ in their response to the uprising.

Willie Pearse’s participation in the Easter Rising came about entirely through his close relationship with his brother, Patrick. He was involved in the planning of it only insofar as he accompanied his brother to meetings, and throughout the rebellion he mostly acted as aide-de-camp to the newly appointed president of the Irish Republic in the GPO. Unique among the executed rebels, he pleaded guilty to the charge that he ‘did an act to wit take part in an armed rebellion and in the waging of war against His Majesty the King’. His guilty plea may have bolstered the case for his execution, but he certainly did not play a significant leadership role in the Rising, and his execution can be linked to the fact that he was the brother of the commandant of the rebels.

All fourteen rebels who were executed as a result of their participation in the Easter Rising in Dublin were shot in the Stonebreakers’ Yard at Kilmainham Gaol. Elsewhere, Thomas Kent faced a firing squad at Cork Detention Barracks and Roger Casement was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London. Although Kent faced the same charge as the Dublin men – participating in an armed rebellion – he was not a leader of the Easter Rising and there was little or no rebel activity in Co. Cork in April 1916. His execution was the result of a military raid on the Kent family home at Bawnard, during which a member of the RIC was fatally wounded. Roger Casement’s involvement in the Easter Rising was over before the rebellion had even started. Casement had been working in Germany to raise support for a rebellion in Ireland and was arrested on Banna Strand, Co. Kerry on Good Friday 1916, after an attempt to land arms for the rebellion failed. His hanging at Pentonville on 3 August 1916 brought to an end the executions of those involved in the Easter Rising.

The rebellion, which started in Dublin on 24 April 1916, was the outcome of a series of events that had begun with the introduction of a Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons on 11 April 1912 by the British prime minister, Herbert Asquith. This was the third attempt to legislate for self-government for Ireland since 1886. However, this time it appeared the efforts of the Liberal Party and their allies in government, the Irish Parliamentary Party, would be successful. The House of Lords had lost its power of veto on bills from the House of Commons in August 1911, and now the way was clear for the enactment of the Home Rule Bill within two years of its passing. The proposed introduction of Home Rule prompted strong opposition in parts of Ulster, with protests concentrated in the four counties in the north-east of the province. The majority unionist, Protestant population there was outraged by what they perceived as a threat to the union of Great Britain and Ireland. On 28 September 1912, Ulster Day, half a million people signed the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant, pledging to oppose the introduction of Home Rule. By the end of the year a volunteer militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), had formed to oppose Home Rule, by force if necessary.

The formation of the UVF prompted nationalists in the south of Ireland to imitate the Ulster unionists by setting up their own military force. The Irish Volunteers were founded at a meeting at the Rotunda Rink in Dublin on 25 November 1913. Unlike the UVF, however, their aim was to defend the introduction of Home Rule in Ireland.

The year 1913 had been an eventful one, particularly in Dublin. In August 1913 William Martin Murphy, a major Dublin employer, instigated an industrial dispute when he ‘locked out’ from their jobs employees who were members of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). The subsequent strike, led by James Larkin and James Connolly, lasted until early 1914, during which time another volunteer militia, the ICA, was formed to protect the interests of workers.

Tensions were heightened in 1914 as the deadline for implementing Home Rule approached. In April 1914 the UVF landed arms at Larne, an event largely ignored by the authorities. The Irish Volunteers staged their own gun-runnings in July and August 1914 at Howth in Co. Dublin and Kilcoole in Co. Wicklow. Soldiers of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, returning to Dublin city centre after their efforts to prevent the landing of arms at Howth had failed, opened fire when a crowd on Bachelor’s Walk began to jeer them. They killed four civilians.

But the event that changed the course of history, and which made the Easter Rising possible, was the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914. The immediate consequence for Ireland was the suspension of the implementation of Home Rule until after the war. On 20 September 1914 John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, made a speech at Woodenbridge in Co. Wicklow in which he encouraged members of the Irish Volunteers to join the British Army, in anticipation that Ireland would be rewarded with Home Rule at the end of the war. This prompted a split in the Irish Volunteers and the vast majority of the estimated 188,000 members followed Redmond and joined a new organisation, the National Volunteers. The remaining men, at most 13,500, stayed with the Irish Volunteers and were led by Eoin MacNeill.

The Irish Volunteers formed the nucleus of the men who would participate in the Easter Rising. At a meeting of key figures in the nationalist movement at the library of the Gaelic League on 9 September 1914, it was decided in principle to stage a rebellion against British rule while the war in Europe was ongoing. The old republican dictum ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’ became the mantra of radical Irish nationalists, including Thomas Clarke, who had long regretted the failure to have an uprising in Ireland during the Boer War, when the British Army was engaged in southern Africa. The planning of the rebellion was carried out by the secret oath-bound organisation, the IRB. Clarke and Mac Diarmada directed the course of events, rejuvenating the IRB with younger members, infiltrating other nationalist organisations such as the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), seeking financial assistance from republican figures in the United States and building a network of like-minded individuals around Ireland. An IRB military committee was formed. Its membership initially included only Pearse, Plunkett and Ceannt, but it was eventually expanded to include Clarke and Mac Diarmada.

By January 1916 preparations for a rising were under way. At this point senior IRB members became concerned that James Connolly, commander of the ICA, was planning on staging his own socialist uprising. Knowing that a small ICA rebellion would scupper plans for their larger rebellion, IRB leaders confronted Connolly. They persuaded him to hold back on his plans for an uprising, and Easter Sunday 1916 was agreed as the date for a joint ICA/Irish Volunteers rebellion.

Not everyone in the republican movement approved of a rebellion, however, not least Eoin MacNeill, president of the Irish Volunteers, and senior IRB figures Bulmer Hobson and Michael O’Rahilly. These men believed an uprising should only occur if there was a strong possibility of success or if the Volunteers were attacked first by the British. MacNeill was kept in the dark and did not learn of plans for the rebellion until the Thursday before Easter Sunday. When he heard on Holy Saturday of the sinking of a German ship carrying arms for the Volunteers off the coast of Co. Kerry, MacNeill decided he should stop the rebellion. Late that evening he issued a countermanding order, published in the Sunday Independent, cancelling all Volunteer manoeuvres for Easter Sunday. Chaos ensued, but at a meeting of the Supreme Council of the IRB at Dublin’s Liberty Hall on Easter Sunday, it was decided that the rebellion would take place the next day.

On the morning of Easter Monday, approximately 1,000 men and women seized control of important buildings across Dublin city, taking the GPO as their headquarters. The Irish Volunteers made up the largest proportion of the rebels and were reinforced by the ICA. It is estimated that 140 women were active participants in the Rising.1 Female members of the ICA were involved in the fighting, while members of Cumann na mBan, the female auxiliary force of the Irish Volunteers, participated by mostly acting as couriers, tending to the wounded and cooking meals for the rebel garrisons.

The effort to hold City Hall was over by Tuesday, but the rebels held on to most of their positions until the evacuation of the GPO on Friday. Overwhelmed by the strength of the British forces and seeking to prevent further civilian casualties, Pearse surrendered to Brigadier General W. H. M. Lowe at 2.30 p.m. on Saturday 29 April. The vast majority of the rebels were brought to Richmond Barracks, where the leaders were identified and court-martialled. Those considered to be ordinary rebels were transferred to Frongoch internment camp in Wales. In total, 186 men and one woman were tried by court martial in the aftermath of the Easter Rising.2 The death sentence was confirmed in fifteen cases and those who were spared execution were imprisoned in England.

The stories of the sixteen men executed following the Easter Rising are not, of course, the story of the entire rebellion. Other figures on the rebel side also played significant leadership roles. Éamon de Valera, commandant of the 3rd Battalion Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers at Boland’s Mills, was sentenced to death. He avoided execution, possibly because he held American citizenship but more likely because he was not court-martialled until 8 May, by which point the British authorities had decided to execute only the most prominent rebel leaders. Constance Markievicz, second-in-command at St Stephen’s Green, was also sentenced to death but spared the firing squad: the execution of a woman would have outraged public opinion. Other prominent rebels were killed in action, including Michael O’Rahilly, shot dead on Moore Street in the retreat from the GPO, Seán Connolly, who led the attack on City Hall and was killed there, and Michael Malone, who was in command at Mount Street Bridge during an attack on British reinforcements marching in from Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire).

In total, sixty-four rebels died in action during Easter Week and sixteen were executed. There were 132 casualties in the British Army and Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) and 230 civilians died as a result of the fighting. It is the stories of the men and women who participated in the rebellion, who witnessed it happening or who tried to suppress it, that make up the narrative of the Easter Rising. But the ‘Sixteen Dead Men’ who were executed for their part in the rebellion became the martyrs of Easter Week and provided the inspiration for the subsequent revolution in Ireland. Their stories did, as Yeats wrote, ‘stir the boiling pot’.

Patrick Pearse

There was little in Patrick Pearse’s childhood and upbringing to suggest that one day he would command a rebellion against British rule in Ireland. The son of an English father and an Irish mother, he was born on 10 November 1879 at 27 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin, the location of the Pearse family home and stone-carving business.

His father, James, was born in Bloomsbury, London, and trained as a stone sculptor in Birmingham. He came to Ireland, possibly in the late 1850s or early 1860s, to take advantage of a boom in church building.1 James Pearse was a self-educated man who read widely on various topics and was most likely an atheist. In 1886 he published a pamphlet in support of Home Rule.

Patrick’s mother, Margaret (née Brady), came from a farming background in Co. Meath; her father later worked in the coal business at the North Strand in Dublin. Her grandfather and great-uncle are believed to have fought in the 1798 rebellion. Margaret was James’s second wife. His first wife, Emily (née Fox), died in 1876. Patrick had a step-brother and step-sister from his father’s first marriage, and an older sister (Margaret), a younger brother (William) and younger sister (Mary Brighid). Pearse was conscious of the diverse backgrounds of his parents and of the influence they had on his development. He later wrote in his unfinished autobiography:

[W]hen my father and my mother married there came together two widely remote traditions – English and Puritan and mechanic on one hand, Gaelic and Catholic and peasant on the other; freedom loving both, and neither without its strain of poetry and its experience of spiritual and other adventure. And these two proper traditions worked in me and, fused together by a certain fire proper to myself … made me the strange thing I am.2

Although he lived for most of his childhood in close proximity to the tenement dwellings of Dublin’s poor at Townsend Street, Pearse’s upbringing was mostly comfortable, as his father’s business prospered. His early childhood was spent in the company of his siblings and cousins, playing with their wooden horse, Dobbin, riding the circular tramline from Westland Row to College Green and later using the magic lantern his father bought him to give slideshow lectures to his family.3 He attended the Christian Brothers school on Westland Row, where he stood out from the other children because of his slight English accent.4 Pearse was a diligent student and it was at Westland Row that he began learning Irish under the tutelage of Brother Maunsell, a native speaker from Co. Kerry. He completed the Intermediate Certificate examinations in 1896, coming second in the country in the Irish exam. At seventeen years of age, he was too young to begin his studies at the Royal University and in the intervening period he taught Irish at Westland Row and founded the New Ireland Literary Society, where members gave lectures on literary topics. In 1898 he began his studies for a Bachelor of Arts degree at the Royal University and also studied for the bar exams at the King’s Inns. Pearse qualified as a barrister in 1901 and never practised as a lawyer, although he did represent a Donegal poet, Niall Mac Ghiolla Bhríde, over his right to have his name painted in Irish on his cart.

The Gaelic League – an organisation founded in 1893 to promote and protect the Irish language – was the focus of Pearse’s professional life in his early adulthood and his involvement made him known in Irish nationalist circles. He joined in 1896 and began attending meetings of the central branch. He quickly came to prominence, becoming a member of the Coiste Gnótha (executive committee) in autumn 1898 and was appointed secretary of the publications committee in June 1900. Pearse showed a level of dedication to the Gaelic League that he demonstrated for other, more political causes later in his life. He missed just six out of 109 meetings of the Coiste Gnótha during his first year as a member of the committee and as publications secretary he rapidly expanded the number of books and pamphlets produced by the Gaelic League.5 The League provided Pearse with a ready-made social circle and he benefited from the travel opportunities presented by the organisation, including trips to Cardiff, Paris and Glasgow.

In March 1903 Pearse was elected editor of An Claidheamh Soluis, the weekly newspaper of the Gaelic League. His plans to expand the paper impressed those who voted for him, although, when implemented, his modernising efforts caused financial difficulties for the League. Pearse’s contributions to the newspaper were non-political and often concerned issues relating to education, particularly the status of the Irish language in schools. A trip to Belgium in 1905, during which he visited schools to see bilingualism in practice and study the use of the Direct Method for teaching languages, provided him with extensive material for his editorials in An Claidheamh.

Pearse’s devotion to the Irish language helped to foster in him a love of the West of Ireland, in particular the Gaeltacht region of Connemara. He learned the dialect of this area and spent his summers living among the native speakers at his summer house in Rosmuck, and he considered the West of Ireland to be the purest living example of an Irish-speaking, Gaelicised Ireland:

In the kindly Irish west I feel that I am in Ireland. To feel so in Dublin, where my work lies, sometimes requires a more rigorous effort of imagination than I am capable of.6

The west also provided Pearse with the inspiration for his writings, including a collection of short stories, Íosagán agus Sgéalta Eile, published by the Gaelic League in 1907. However, Pearse had a tendency to romanticise life in the West of Ireland and ignore the poverty experienced by the people living there. He wrote articles in An ClaidheamhSoluis opposing emigration from the west as it contributed to the decline of the language, but he failed to acknowledge the economic realities that forced people to leave their homes.

Pearse’s research and writings on education eventually brought him to a decision to establish his own school for boys. Scoil Éanna, or St Enda’s College, was to be different from any other school in Ireland at that time. The Irish language and culture would be at the heart of the school, new teaching practices – including the Direct Method and bilingual teaching – would be utilised, the curriculum would include modern subjects, including European languages, zoology, shorthand and book-keeping, and students would experience a holistic education with an emphasis on sport, drama and other activities. St Enda’s opened at Cullenswood House, Ranelagh, in September 1908. Pupils included the sons of important members of the Gaelic League and the school had high-profile supporters, including Douglas Hyde, Eoin MacNeill, W. B. Yeats and Padraic Colum, all of whom gave lectures to the boys during the first school year. Kenneth Reddin, a former pupil of the school, summed up his sense of what made St Enda’s different to other schools:

The atmosphere of St Enda’s was completely un-institutional. I have never looked into the Refectory of any great Public School and sensed its bareness and cleanliness without thinking of a prison, a reformatory, or a hospital. The atmosphere of St Enda’s was neither that of a prison, a reformatory, nor a hospital. In fact at night we often went down to Mrs Pearse for a biscuit or, if that failed, for a slice of bread and a glass of milk, or to Miss Pearse or Miss Brady. … And in the Refectory we all ate together, Headmaster, teachers and students. We lived en famille, and in full family atmosphere.7

In 1910 Pearse decided to relocate the school to a more rural setting in Rathfarnham, South Dublin, and he obtained a lease on a large house called the Hermitage, which was surrounded by extensive grounds. He also established a school for girls, Scoil Íde, at Cullenswood House. The move to Rathfarnham had disastrous consequences for the school, as Pearse could not afford to rent the Hermitage or pay for the expensive alterations required. Fewer day pupils attended because the school was too far from the transport network of the city centre. Pearse’s financial difficulties continued until the end of his life.

Pearse was a shy person and was something of an outsider at social occasions. Some of his insecurity was brought about by the fact that he was self-conscious about a cast in his left eye. He always posed for photographs in profile so that the cast would not be seen. Pearse’s closest friend was undoubtedly his brother, Willie, who taught art at St Enda’s. Willie was Patrick’s confidant and could influence his actions. Their mutual friend Desmond Ryan later wrote: ‘Pearse listened most courteously to all critics and went on doing as he liked until Willie lisped his fierce word’.8 Pearse never married, although he was linked romantically to Eveleen Nicholls, who drowned while swimming off the coast of Kerry in 1909. Although he had some close friendships with women – he holidayed in the West of Ireland with Mary Hayden, a colleague in the Gaelic League, seventeen years his senior – Pearse could behave quite awkwardly in female company.

Pearse first came under the influence of ideas around Irish independence when he moved his school to Rathfarnham in 1910. One of the reasons Pearse chose to relocate to the Hermitage was its association with one of the great heroes of Irish nationalism, Robert Emmet, who was executed for his leadership of a small rebellion in Dublin in 1803. Emmet was believed to have courted his love, Sarah Curran, in the grounds of the Hermitage, which was situated near her home. Shortly after the move to the Hermitage, Pearse began reading the writings of the republican leader Theobald Wolfe Tone and the Jail Journal of John Mitchel. Emmet, Tone and Mitchel greatly influenced the development of his nationalist thinking.

Pearse first came to prominence in advanced nationalist circles when he was asked by Seán Mac Diarmada to speak at a Robert Emmet commemoration in 1911. Mac Diarmada and his close associate Thomas Clarke were key figures in the IRB – the secret underground organisation responsible for the planning of the Easter Rising – and they were impressed by his speech.

However, up until 1912 Pearse’s interest in politics was mostly confined to the Irish language and education policy. His development as an advanced nationalist came later. As late as March 1912 he spoke at a rally on Sackville Street, Dublin, in support of the Third Home Rule Bill, introduced to parliament by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Pearse spoke in favour of the prospect of limited self-government for Ireland, but warned that if the bill was not passed there would be war in Ireland.

Pearse felt that he needed an Irish language platform from which to express his developing political ideas and he founded a newspaper in 1912, An Barr Buadh, which ran for eleven issues. He also contributed articles to the radical newspaper Irish Freedom.

Pearse’s growing involvement in Irish politics coincided with an extraordinary period in Irish history during which new organisations were formed to try to determine the future of Ireland. The prospect of Home Rule was strongly resisted by the majority Protestant population in north-east Ulster. In September 1912 nearly half a million men and women signed the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant, pledging to defend the province from the introduction of Home Rule. Four months later 100,000 men who had signed the Covenant joined the UVF, a militia which aimed to resist Home Rule by force. The landing of arms by the UVF at Larne in April 1914 demonstrated that the organisation was serious in its intent.

Meanwhile, in Dublin nationalists began to suggest the formation of a similar organisation to protect Home Rule. In an article, ‘The Coming Revolution’, published in November 1913, Pearse wrote: ‘I am glad that the Orangemen have armed, for it is a goodly thing to see arms in Irish hands. … I should like to see any and every body of Irish citizens armed’.9 That same month, Eoin MacNeill raised the prospect of forming a militia in the south in an article in An Claidheamh Soluis, entitled ‘The North Began’. A meeting was held at Wynn’s Hotel, Dublin, on 11 November 1913 to discuss the formation of a militia, and it is indicative of Pearse’s growing importance in nationalist circles that he was invited to this meeting.