17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: A Day

- Sprache: Englisch

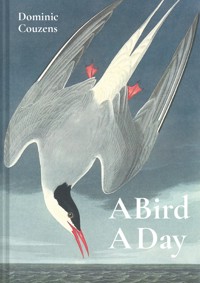

'Perfect for dipping into, beautifully written, and great to look at.' – Birdwatching 'An ideal reference book for fledgling ornithologists.' – The Field The beauty and fascination of birds is unrivalled. Every day of the year, immerse yourself in their world with an entry from A Bird of Day, where Dominic Couzens offers an insight into everything from the humble Robin to Emperor Penguins, who are in the midst of Arctic storms protecting their young on 1 July. Or discover the fate of the Passenger Pigeon which became extinct through overhunting on 1 September 2014. If you ever visit the Himalayan uplands, go in late November when you can see a flock of the cobalt blue Grandala birds, which is one of the wonders of the natural world. The author is a world expert on birds and particularly bird behaviour and he reveals endless fascinating stories of birds from all over the globe to give a rich tapestry of avian life with stunning photography, illustration and arresting art. All of bird life is covered, from nesting, migration, and courting to birdsong and curious bird behaviour. From the promiscuous Fairywren of Australia, who gives petals to his mistresses, to the singing instructions of the female Northern Cardinal in North America, this is a delightful dip-in-and-out book for any nature lover.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

A BIRD A DAY

CONTENTS

Introduction

JANUARY

FEBRUARY

MARCH

APRIL

MAY

JUNE

JULY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

Picture Credits & Further Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

There isn’t a day of the year when birds aren’t around us, visible and audible. There isn’t a day when, assuming our circumstances allow it, we cannot see them and enjoy them – if only briefly out of a window, or the corner of our eye, or as part of our life’s soundtrack. Birds are ubiquitous and global. There are only a handful of places in the world where there aren’t birds.

This book celebrates that fact. Its real aim is to encourage and inspire people to look at birds, whenever and wherever they can. Hopefully, it can open a window on the wonderful world of birds, because the world of birds is awe-inspiring.

According to the latest official list, compiled by the International Ornithological Congress, there are 10,770 species, plus another 158 that have become extinct since the beginning of the 16th century. That means that there are 10,928 birds that are known to people. That is undoubtedly the tip of the iceberg of the number of species that have evolved since birds first arose about 150 million years ago.

This book celebrates one species a day. It could be 30. Every bird species has a story. You could write this book ten times over and still have interesting stories left. However, for the purpose of actually producing a publication, it has been necessary to be selective, and the 366 species included (including one for the leap year) are hopefully a satisfactory range from the glittering array available.

The process of selection has various stages. Some birds pick themselves; if you had to pick, say, 366 actors, then some are so famous or charismatic, or currently fascinating, that you couldn’t possibly leave them out. So it is with a bird such as an ostrich – unique, iconic and world famous. It’s the same for albatrosses and penguins and birds of paradise.

Other species you cannot leave out include those that have a place in our cultures, so they are significant for our interactions with them. These are many and varied but include birds we consume and hunt, species such as chickens (red junglefowl), turkeys and grouse, those in literature (poems, stories) and those that are intimately wrapped up in our different lives and cultures – emus to aboriginal Australians, common loons to native Americans and peafowl to Hindus, among many others. Some of their cultural stories are told in this book.

Hand-colored lithograph, published in 1880 showing 1) Bird-of-paradise, 2) Hawfinch, 3) Guianan toucanet, 4) Green-crowned plover crest, 5) Red crossbill, 6) Wallcreeper, 7) Eastern ground parrot, 8) European roller, 9) African grey parrot, 10) Lapland longspur, 11) Collared flycatcher, 12) Rhinoceros hornbill, 13) Eurasian nightjar, 14) European goldfinch, 15) Crag martin.

Some birds are scientifically significant. The last few decades have been awash with pioneering research, and the advent of such advances as DNA fingerprinting and satellite tracking have unveiled many remarkable facts. Birds do extraordinary things and their lives are much more complicated that anyone imagined 40 years ago. Many of the best discoveries are included in this book.

Of course, in a particular book like this you must also include characters that are seasonally significant. Birds have seasonal resonance – just think of the arrival of a swallow in the northern hemisphere in spring, and then of the same bird in the southern hemisphere in their spring. Think of geese and cranes arriving in autumn to various points around the globe. Think of the swelling of bird songs in the rainy season in the tropics, or before the monsoon. Around the world, the arrival of certain birds in certain places has heralded delight and understanding. Throughout this book I have tried to place birds on appropriate days, with migratory movements, song delivery or breeding signs in mind.

Parrots. Chromo-lithograph 1896.

Finally, there are some birds that remind us that our world is in dire need of conserving. Sprinkled through the book are stories of endangered birds, some with unhappy endings, but many with ongoing hope. I have included some anniversaries of extinction dates, but also some where a species’ fortunes turned.

As we all know, though, our earth is changing, and the danger to all life on earth has become apparent, through climate change and many other factors. There is a real possibility that some of the seasonal resonance of bird arrivals and departures will diminish in the future.

So there are many reasons to include a bird in this book, but perhaps the most important is to heighten knowledge and respect for wild creatures in general. The future of birds on this planet partly depends on conservationists winning the hearts and minds of people around the world, so that they can accept the political and cultural changes that will help save the environment. If a book like this can make a very small contribution towards more people loving birds, it will have been worth writing.

Akeel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus) encounters a montezuma oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma) in Costa Rica.

1ST JANUARY

RED-CROWNED CRANE

Grus japonensis

It’s the New Year, a time when we all hope for peace and longevity. No bird symbol represents these quite like the red-crowned crane, a bird steeped in the culture of the Far East. For centuries it has been depicted in art and legend.

In China, the red-crowned crane represents immortality. In Japan, it was once believed that it could live for 1,000 years. It is also a symbol of fidelity; the cranes do indeed mate for life.

These days the red-crowned crane is a rare bird, with a world population of only around 3,000. The longevity of the species itself is far from assured.

A pair of red-crowned cranes dance the New Year away in Hokkaido, Japan. The species also breeds in China.

2ND JANUARY

COMMON KESTREL

Falco tinnunculus

For the sheer joy of observation, and the sheer joy of language leaping in all directions, it is hard to top Gerard Manley Hopkins’ description of a kestrel in ‘The Windhover’, a poem he wrote in Wales (UK) in 1877.

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

The kestrel hovers in just this way above open ground, searching for its staple diet, small mammals.

The common kestrel hovers over open ground everywhere from western Europe to far-eastern Russia. Small mammals are the main prey.

3RD JANUARY

WANDERING ALBATROSS

Diomedea exulans

King of the Roaring Forties, the wandering albatross rides out the wrath of the Southern Oceans with barely a wingbeat. With a 3.5m (11½ft) wingspan, the greatest of any bird, the albatross is perfectly adapted for gliding, its slender wing shape promoting lift and reducing drag. It can travel enormous distances over the oceans, expending little or no energy, harnessing the power of the wind and the waves. It routinely travels 2,000km (1,250 miles) just to go foraging for its young in the nest.

Recent radio tracking has shown that parents foraging from the sub-antarctic Crozet Islands in the Indian Ocean (46°S) go in search of food in different directions: the males go south and clockwise, the females north and anti-clockwise.

Now is the middle of the egg-laying period for wandering albatrosses on the few islands where they breed in the southern oceans.

4TH JANUARY

GOLDEN EAGLE

Aquila chrysaetos

These magnificent birds of prey inhabit huge tracts of wild, remote country, where they terrorize a wide range of prey, from medium-sized birds such as grouse, to mammals like rabbits and hares. It is claimed that they can spot a mountain hare from a distance of 2km (1¼ miles), such is their visual acuity.

These birds use a variety of techniques for hunting. One of the more remarkable is to chase large animals to a place of great peril – so, for example, they might corner a young ibex on a precarious rock face, causing the unfortunate animal to lose its footing and fall to its death.

The golden eagle’s main foraging technique, however, is flushing, in which the eagle flies low over wild country, following the slopes, hoping to come across prey and surprise it into the open. Pairs of golden eagles practice this method in tandem, one bird performing the flush, the second making the kill.

A remarkably widespread and successful eagle, inhabiting much of North America and Eurasia, mainly wild, treeless country.

5TH JANUARY

GREAT TIT

Parus major

Although it’s only the beginning of January, throughout Europe male great tits are already in full voice. Their cheerful, breezy ‘Teacher, teacher’ song chimes across the bare winter woodlands and their brilliant colours are telling. Birds from deciduous woodland, which is high-quality habitat, have brighter breasts than those born in coniferous woodland. The latter is marginal great tit habitat, so those raised there are from the wrong side of the tracks – and, to a potential mate, that shows.

Abundant bird of Europe, the Middle East, central and northern Asia.

6TH JANUARY

EURASIAN WREN

Troglodytes troglodytes

A strange folk ritual known as Wrenning used to take place in parts of the British Isles and Ireland. People would go out on Twelfth Night (6th January) or St Stephen’s Day (26th December), wearing fancy dress and beat the vegetation to flush out a wren. They would catch the wren and either put it in a cage or nail the unfortunate bird to a pole. The captors would then walk from house to house asking for gifts of food and drink in exchange for wren feathers.

A songbird of dense vegetation in Europe and Asia.

7TH JANUARY

MUTE SWAN

Cygnus olor

Swans are magnificent birds, with their crystal clear, white plumage, long necks and marvellous, imperious flight with slow, powerful wing beats. They are among the heaviest of all birds, with a male mute swan weighing in at 10kg (22lb) and a female 8kg (17½lb). They need a long run, with much foot-pattering, just to take off; the wide-bodied jets of the bird world.

The mute swans is unusual among swans for its relative silence, although it grunts regularly and will make whining sounds. The other swans, however, make loud, bugling or twanging calls, and their flocks are a babble of conversation. No wonder its English common name is ‘mute’.

But this swan does have a song, it is just that it is made by its wings. As the bird flies, the primary feathers swish in the air to produce a sweet, rhythmic sighing. This marvellous sound is audible for up to 2km (1¼ miles), so the flock can easily stick together and not bother to open their mouths.

Mute swans are found in Europe and western Asia; some populations migrate south in winter. Introduced to North America.

8TH JANUARY

DARK-EYED JUNCO

Junco hyemalis

To many in North America, juncos are the ultimate winter birds. Breeding in the far north, from Alaska to Labrador, they spill south in autumn and gather into flocks that are a familiar sight in backyards, woodlots, parks and suburban areas. Handsome, with their white outer tail feathers and bold plumage, many still refer to them as ‘snowbirds’, as renowned naturalist and painter John James Audubon did in 1831. They live as many human snowbirds do, taking up winter residence in warmer climes to escape the chill back home.

Juncos (the name is thought to come from Juncus, a genus of rushes, although juncos are not birds of wet areas) come in a number of colour forms, especially in the west. These were once recognized as separate species.

Dark-eyed juncos breed across northern and upland parts of North America, in various types of forest; mainly in winter south of the Great Lakes.

9TH JANUARY

ZEBRA FINCH

Taeniopygia guttata

If you’re a male zebra finch, a small nomadic bird found in arid parts of Australia and Indonesia, you should be suspicious of the gender of your offspring. If your mate tends to produce females, the chances are that she doesn’t think much of you.

Some female birds, including zebra finches, are able to manipulate the sex ratio of their offspring, although how they do this is unknown. If their mate is particularly attractive, they tend to produce more male offspring, since it pays for the father’s good genes to be passed on. However, if their mate is nothing special, they produce more female offspring, since there is no point producing yet more inadequate males!

These finches are common across arid regions of Australia and some Indonesian islands; a popular cage bird.

10TH JANUARY

LONG-TAILED TIT

Aegithalos caudatus

On cold nights in January, long-tailed tits huddle tightly together. This close bodily contact means that they lose heat at a slower rate.

These long-tailed tit huddles involve family members, including the mother and father, the previous brood and some adult relatives. Surprisingly, the adults take the warmest positions in the centre, leaving their offspring to cope with the chilliest, most perilous spots around the outside of the huddle.

These gregarious birds are found in small flocks in woodland all across Europe and Asia as far east as Japan.

11TH JANUARY

LITTLE PENGUIN

Eudyptula minor

It’s easier than you think to see a wild penguin. Most people think they are only found in the Antarctic, while some, including film makers, mistakenly believe they live cheek by jowl with polar bears in the Arctic. In fact, any suitably chilly water in the southern hemisphere will do, including around Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and southern South America.

Probably the easiest of all to see are the little penguins found in Australia and New Zealand, where a handful even live wild in Sydney Harbour. There is a permanent viewing platform on Phillip Island, near Melbourne, where visitors can pay to see the birds coming ashore on Summerland Beach.

The world’s smallest penguin breeds all year round on the sandy and rocky islands and coasts of southern Australia and New Zealand.

12TH JANUARY

‘I’IWI

Drepanis coccinea

We should be grateful that the gorgeous ‘I’iwi still exists in the world. This lovely bird with its crimson plumage, remarkable curved bill and vivacious manner is a member of a group of birds called Hawaiian honeycreepers. Their populations have slumped dramatically since the arrival of human settlers on the remote Hawaiian archipelago. No less than 18 of the 39 recognised species are now extinct.

The biggest cause, besides the usual issue of loss of habitat due to deforestation, has been an unusual one: malaria caused by introduced mosquitoes. Ninety per cent of all ‘I’iwis bitten by a single infected mosquito die, and 100 per cent of all individuals bitten more than once. Only places above 1,300m (4,250ft), where it is too cold for mosquitoes, remain safe for these birds.

Pronounced ‘ee-EE-vee’ this vibrant bird uses its curved beak to drink nectar. It can be found on the main islands of Hawaii, Maui and Kauai; all but lost from Molokai and Oahu.

13TH JANUARY

WHITE-WINGED CHOUGH

Corcorax melanorhamphos

The hardships of the Australian dry country make birds do some very strange things, and none more so than the white-winged choughs.

These birds live in family groups, based on an adult pair and their offspring from previous years. The group defends its territory from neighbouring groups, sometimes violently, and the birds spend each day foraging together on the ground. When it comes to breeding, the adult pair build a nest out of mud, and everybody contributes to raising each year’s young.

Raising young is hard, even with co-operation, and the largest groups of choughs have the best chance of success, since these have the most helpers. Because there is a direct relationship between the size of the group and nesting success, some groups resort to extreme measures to increase their flock size. They do so by kidnapping the youngsters from neighbouring groups during disputes!

Just now the young choughs are hatching and being fed in the open eucalypt woodlands of eastern Australia.

14TH JANUARY

ANDEAN CONDOR

Vultur gryphus

The world’s largest bird of prey, with a wingspan of up to 3.2m (10½ft)and a weight up to 15kg (33lb), the Andean condor is the last remaining massive scavenging bird in South America. There were once raptors with wingspans up to 6m (19½ft) soaring over the plains here, feeding on the carcasses of prehistoric megafauna while the Andes were still foothills. Nowadays the condor is only rivalled by a few albatrosses, swans and pelicans as the world’s largest flying bird of any kind. It soars effortlessly over Andean peaks and patrols the cliffs bordering the oceans. Its huge size, colourful face and gorgeous white-centred wings render it unmistakable.

It looks fierce but is no more than a scavenger, eating the carcasses of large animals, often domestic ones such as sheep or llamas. On the coast, dead sealions or whales suffice.

The condor has been idolised by people for at least 4500 years. In Andean mythology it is associated with the sun god, and the Upper World. In more recent times it has been the object of the remarkable, elemental Yawar Festival, which takes place in many Peruvian villages. A condor is captured and tethered to a bull, the latter of which is knifed to death by the villagers, who set the condor free when the bull expires. The ceremony marks the release of the Andean peoples, represented by the condor, from their Spanish oppressors, represented by the bull.

Found all year round in the Andes of South America, from Colombia to Tierra del Fuego, condors can live as long as humans.

15TH JANUARY

GREAT CORMORANT

Phalacrocorax carbo

Cormorants are water birds that aren’t waterproof. At first glance this makes them seem utterly unsuited to a life of immersive fishing, as if they were pilots afraid of flying. The reality, though, is that having feathers that quickly become saturated with water reduces the bird’s buoyancy and allows it to pursue fast-moving fish underwater without too much drag. When diving, cormorants hold their wings at their sides and steer using their tail and the webbing of their feet.

The cormorant’s dense bones and reduced body fat also ensures that they sink easily; they occasionally swallow stones for the same purpose. However, there is a downside for this saturated bird when it returns to land. It must spend hours holding its wings out to dry – and that, indeed, is often our most familiar image of this bird.

The non-waterproof cormorant has to hang itself out to dry. This successful waterbird is found in Europe, eastern North America, North Africa, parts of Asia and Australia.

16TH JANUARY

ROOK

Corvus frugilegus

In the bare trees of a northern winter, the script is written by the network of stark, leafless twigs writing against the colour-drained sky, denuded by the ravages of autumn and with the green light of spring still far away. Here, though, on a warmer day, the heart can be lifted by the sight of rooks refurbishing their nests. Exceptionally early breeders, these loquacious colonial birds are responding to inner impulses governed by the increasing day-length from late December onwards. Their timetable is internally programmed, and despite the meagreness of the season, their stick-arranging proves the inevitability of what is coming.

Rooks and their rookeries can be spotted over much of Europe and Asia where fields and woods intermix.

17TH JANUARY

CROWNED EAGLE

Stephanoaetus coronatus

Africa’s crowned eagle is not the world’s largest eagle – that’s the harpy eagle of South America – but it is certainly among the most ferocious. It has unusually large talons, too, and this has earned it a very rare distinction: it is occasionally inclined to prey on humans.

There are several documented records of the crowned eagle attacking children; the skull of a child has been found in a nest. As the birds rarely, if ever, scavenge dead bodies, the child was probably killed as food for the young. On another occasion a severed human arm was found among a crowned eagle cache. And a seven-year-old boy was witnessed being attacked and badly injured by an eagle that was killed during the attempt.

An African man-eater, found south of the Sahara.

18TH JANUARY

GREAT SPOTTED WOODPECKER

Dendrocopos major

It’s mid-January, and the forests of Europe and Asia resound, on fine days, to the atmospheric ‘drumming’ of the great spotted woodpecker. The sound is made by the bird striking wood with its bill ten or so times in less than a second.

The distinctive noise, though, is not the sound of a bird drilling a hole. It is purely for show, a replacement for the song of other birds, to advertise an individual’s presence. It is like a drum roll, hitting a surface to make a sound, but not damaging it.

The ‘tree striker’ resides in all kinds of woodlands in Europe and Asia.

19TH JANUARY

WHOOPER SWAN

Cygnus cygnus

Swans have enthralled humankind for millennia. That much is clear from artefacts found in Eastern Siberia, at a site called Mal’ta, near Irkutsk. Depicting birds with long necks and heavy bodies, they are carved from mammoth tusks and are thought to be 15,000 years old.

Imagine that: our ancestors would have heard the bugling calls of swans as they hunted the long-extinct mammoth.

The whooper swan is still going strong in North Eurasia, migrating south in winter.

20TH JANUARY

SNOWY OWL

Bubo scandiacus

The big cat of the bird world, with its piercing yellow eyes, luxuriant plumage and brilliant white coloration, the snowy owl is one of the great symbols of the Arctic, together with polar bears and reindeer. In common with big cats, its looks bely its character, which can be extremely aggressive. Humans and other predators, such as wolves, have been attacked and injured by these great birds.

In common with several other Arctic predators, snowy owls depend largely on the tundra’s production line of small mammals for food. They are particularly fond of lemmings – those supposedly suicidal rodents (it isn’t true that they jump off cliffs) – and a single owl may consume around 1,600 of these a year.

Amazingly, some snowy owls remain in the Arctic all winter, even where the darkness does not relent. Here they often live near human settlements, using what light there is to hunt.

Although widespread, snowy owls are thinly scattered across the high latitudes of North America and Eurasia.

21ST JANUARY

LAUGHING KOOKABURRA

Dacelo novaeguineae

This Australian icon is part of the country’s incredible dawn chorus. Well before it gets light, this chunky, brash bird will launch into its laughing call, and often the two members of a pair will sing in chorus. As a laugh, it is definitely on the hysterical end of the scale, becoming louder and more out of control as it goes on; a slapstick start to the day.

Those who are familiar with the Eurasian kingfisher – small, bejewelled and charming – are amazed when they hear that the kookaburra belongs to the same bird family. Hefty, plain-coloured, shunning rivers and impossible not to see – indeed, adorning powerlines, signposts, gum trees (of course!), fences and even barbecues – it is as far from the European perception of a kingfisher as it is possible to get.

It doesn’t eat fish, either. It is a bird of dry country, with a voracious appetite for large insects, lizards, small mammals and occasionally snakes. The famously venomous spider fauna of Australia also takes a battering. The hunter simply sits on an elevated perch, scanning below, and slips down to snatch what it finds.

The largest member of the kingfisher family lives in open forests in eastern Australia and the far south-west.

22ND JANUARY

MARABOU STORK

Leptoptilos crumenifer

It’s fair to say this is no one’s favourite African bird. It is unattractive on a continent overflowing with colourful birds, it has revolting feeding habits and hangs out in insalubrious places such as rubbish tips, looking distinctly sinister.

This is a stork identifying as a vulture. It is a scavenger that occupies the fringes of vulture scrums, running in to pick up dropped scraps, or even mixing in at the carcass.

The marabou also, though, has a sideline in predation. At rubbish tips it eats rats and mice, which is very helpful to the human population. It also eats flamingos at their colonies, catching and drowning them, and then tearing them apart.

The ‘undertaker bird’ is common in Africa south of the Sahara.

23RD JANUARY

WHITE TERN

Gygis alba

An apparition from tropical seas sometimes called the angel tern, this pure white beauty with soothing dark eyes builds one of the most remarkable nests in the world – and that is no nest at all. It simply lays its single, speckled white egg precariously perched on a bare branch. No frills.

The nest of the white tern is no nest at all! Widepread over tropical oceans, many populations are breeding now.

24TH JANUARY

GREY-HEADED ALBATROSS

Rhalassarche chrysostoma

After breeding, adult grey-headed albatrosses take a sabbatical to spend the next year wandering the oceans. Some simply set their wings to the wind and circumnavigate the globe, and some even do this twice! One radio-tracked individual from Bird Island, South Georgia, flew around the world in 46 days. That’s an average of almost 600 miles (950km) per day.

These birds have also been tracked flying at over 80mph (130km/h) during a storm.

Widespread across southern oceans, breeding on islands.

25TH JANUARY

DOWNY WOODPECKER

Dryobates pubescens

A backyard bird over most of North America, the downy woodpecker is the pint-sized version of woodpeckerdom. It uses its diminutive stature to climb up weed stems as well as tree trunks, and to forage far out in the topmost, spindliest twigs of the canopy, foraging sites out of the reach of larger woodpeckers.

This bird demonstrates how, among birds, males and females may have significantly different ecological niches. Male downy woodpeckers almost always use the thinnest twigs and branches and consequently forage higher up and lower down (on snags and weeds) than females, which use trunks and branches with a greater diameter. When males are experimentally removed, the females will venture into the niches left behind.

Averaging only 15cm (6in) in length, this small woodpecker is common throughout most of North America in any wooded habitat; also gardens.

26TH JANUARY

EMU

Dromaius novaehollandiae

Today is Australia Day. The emu is the national bird of Australia and aptly so, for it has been part of the way of life of Aboriginal communities for many thousands of years. It has long been appreciated as a source of meat, and the fat has been used as a lubricant and as a dressing for wounds. Every part of the bird was used. The feathers were, not surprisingly, used as adornments in rituals, the eggs were eaten and the eggshells used as small carriers for water. The long leg bones were sometimes used for more gruesome purposes – as a spear to pierce the chest of an enemy who lay sleeping.

The Aboriginal peoples caught emus in many ways, none more ingenious than poisoning the tall, flightless birds’ water supply. The hunters would crush the dry leaves of the pitchuri thornapple, a plant containing nicotine and nornicotine, and use the powder to contaminate small waterholes. The birds would drink, become stupefied, and were easy to kill.

This iconic flightless giant has been found throughout mainland Australia for millennia, as shown by this 2,000-year-old aboriginal depiction of emu feet found at Carnarvon Gorge, Queensland.

27TH JANUARY

SCARLET ROBIN

Petroica boodang

In the history of European settlement, it was common for people to give the animals and birds of their new land epithets that were familiar back home. It probably gave comfort to homesick people. Sometimes the result is a little incongruous, though. The New World warblers don’t warble. And the American robin – well, it’s not even a robin on steroids.

At times, though, the glove fits, and this is certainly the case for the delightful scarlet robin, of Australia. DNA studies show that it isn’t at all closely related to a European robin, but in its habits it is remarkably similar, as well as bearing that smart scarlet breast. It is, for example, similarly a perch-and-pounce insectivore: both species perch above the ground on the lookout for small invertebrates, which they then swoop down to catch. Both are territorial. The similarity also extends to some of their breeding behaviour. The female builds the nest, for example, but the male provides her with food to keep her going, passed from bill to bill.

The similarities come from convergent evolution; the convergent naming came later.

The eucalypt forests of south-east and extreme south-west Australia and Tasmania are the territories of this monogamous bird.

28TH JANUARY

WHITE-EYED RIVER MARTIN

Pseudochelidon sirintarae

On the evening of 28 January 1968, a small bird flopped into a net at Bung Boraphet, an artificial lake in central Thailand. A swallow-like bird, it was taken to local zoologist Kitti Thonglongya, who immediately realised from its large white eyes and velvety plumage that it was something completely new to science. This was astonishing, bearing in mind that Thailand had been well explored by ornithologists for more than 100 years and Bueng Boraphet was nothing more exotic than a big lake (previously a swamp) in a large area of human population, the last place you might expect to find something new.

The following night another was captured, and on 10 February 1968, seven more. The next winter another appeared. A pair was delivered to Bangkok Zoo in 1971 and six were seen over the lake on 3 February 1978.

And that was it. The white-eyed river martin was never seen again. Where it came from and where it went is a complete mystery.

Recorded in winter from a lake in Thailand, breeding grounds unknown. Probably extinct.

29TH JANUARY

INDIAN VULTURE

Gyps indicus

It wasn’t long ago that the skies above India swirled with vultures, riding the plumes of warm air above the seething melting pot of humanity. Unloved, but usually unhindered, vultures and kites thrived in unsanitary corners, performing an astonishing clean-up service, relishing the ever-present reality of death and decay. Such was their efficiency and ubiquity that they inveigled their way into human culture, most notably that of the Parsis, a Persian minority concentrated in southern India.

Quite simply, the Parsis adopted the practice of letting the vultures dispose of their dead, a tradition known as ‘sky burial’. After death, the human bodies would be taken up a moderately tall, fortified tower known as a dakhma (often colloquially called a Tower of Silence) where, after the funeral, they were exposed to the elements and to flesh-eating birds.

In the 1980s and 1990s, however, a catastrophe occurred when a drug called diclofenac began to be used as an anti-inflammatory for livestock. It proved toxic to vultures and the population crashed. From a population of 80 million in the 1980s, the numbers have sunk to a few thousand. The result is a crisis of sanitation. Other scavengers, including feral dogs, have vastly increased, while rates of infection have also soared. And, for the moment, the Parsis are having difficulty effectively disposing of their dead.

Once abundant throughout India and Pakistan, the population has crashed, and is now very localised.

30TH JANUARY

GURNEY’S PITTA

Hydrornis gurneyi

Pittas are probably the most beautiful birds in the world that you’ve never heard of. Found in the leaf litter of forests in tropical Asia, Australasia and Africa, they are secretive birds which, despite their gaudy plumage, are difficult to see in the half-light of the shade where they hunt. Each of the 30 or so species is breathtakingly colourful or boldly patterned. You would think that they would be among the best known of all birds, along with the similarly scintillant hummingbirds and birds-of-paradise.

Take a look at the Gurney’s pitta. This bird, among the most beautiful of all, is on the verge of extinction. Can you imagine a world without it?

Vanishingly rare in one rainforest in Thailand and a few in Myanmar.

31ST JANUARY

AMERICAN FLAMINGO

Phoenicopterus ruber

Everyone knows flamingos: they are tall, pink and strange-looking. But in spite of this, everything about them makes sense. Flamingos have existed for 10 million years; their body plan works.

Take those long, bare legs. Flamingos often feed in hypersaline water, so it pays not to immerse too many feathers that might become encrusted with salt, or otherwise damaged. The birds need to be tall so that they can wade at different depths, and their necks must also be long enough to reach the water. Flamingos can also swim, using their webbed feet.

And what about the colour? It is certainly unusual but is simply the by-product of what the birds eat, which in the case of the American flamingo is crustaceans and algae rich in carotenoid pigments.

And what of their curious bill, oddly bent in the middle? Well, flamingos are filter feeders, and their bills are fitted above and below with tiny, comb-like structures called lamellae which together overlap and form a sieve from which small items in suspension can be trapped. The tongue is used as a piston to force water through the network of lamellae.

This filter system only works when the bill is slightly open. The advantage of the bent bill is that, when it is open, the space between mandibles remains the same from base to tip. If the bill was straight, the gap between the mandibles would be wider at the bill tip and very narrow at the base, making the filtration system less effective.

These flamingos take 2–3 years to gain their full hot-pink colour. They are localised around Caribbean, Central America and the Galapagos Islands, usually in salty lagoons.

1ST FEBRUARY

NORTHERN GANNET

Morus bassanus

With its 2m (6½ft) wingspan and gleaming, clean white plumage with crisp black wing-tips and butterscotch-infused crown, the northern gannet is an impressive seabird – and even more so when it plunge-dives into the sea to catch fish, sometimes from a considerable height, occasionally 30m (100ft). It hits the water head-first at speeds up to 95km/h (59mph), closing its wings at the last minute to maximize speed. To prevent damage, the gannet’s nostrils open internally into the bill-chamber; otherwise the water would rush up its nose.

The dazzling plumage may help gannets to congregate easily at a food source. They can see one another from such a great distance that, if one begins plunge-diving, others far away will spot the action, and birds even further away will see their neighbours change course towards the commotion. The presence of many plunge-diving predators confuses and panics the shoals of fish, potentially making them easier to catch.

The northern gannet breeds on cliffs and islands of the North Atlantic and flies mainly over shelf waters.

2ND FEBRUARY

LAKE DUCK

Oxyura vittata

Birds don’t exhibit much in the way of penises. On the whole, a coming together of reproductive organs is enough for fertilization to take place, with little or no intrusion required. However, there are certain situations where a penis, or more correctly a ‘cloacal phallus’, is highly necessary. Birds that copulate on unstable surfaces, such as water, need a little more purchase. Or, in the case of Argentina’s lake duck, a lot of purchase. This species holds the record for the longest avian penis. At 42.5cm (16¾in), it is as long, or even longer than the bird itself, and longer than that of an ostrich (just 20cm/8in). The penis is spiral-shaped and can be retracted after use.

Why the lake duck is so richly endowed is not known.

This record-breaking duck can be found on freshwater lakes and wetlands in southern South America.

3RD FEBRUARY

GREAT ARGUS

Argusianus argus

Argus was the hundred-eyed giant of ancient Greek mythology. He was charged by the goddess Hera with protecting the priestess Io, who had been transformed into a cow, the sort of thing that seemed to happen a lot in those days. Unfortunately, Argus was killed by Hermes, and thus failed in his mission. His eyes were thrown by Hera into the tail of a peacock. And, don’t you know it, the peacock has overshadowed the argus ever since.

The great argus occurs in warmer tropical regions than the peacock, in south-east Asia, usually in thick forest. Its call is a purer, less clanging effort, sounding like an impressed ‘Oh, wow!’ Its display is similar, with the tail coverts fanned almost all around the face and body, but its many eye spots are not as large or ornate. Nonetheless, without the brilliance of the peacock, the great argus, bearing some of the longest feathers in the whole bird world, would probably be just as famous and renowned.

This pheasant is native to the dense forests of the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra and Borneo. Displays are beginning about now.

4TH FEBRUARY

RED JUNGLEFOWL (DOMESTIC CHICKEN)

Gallus gallus

Today is as good as any day to celebrate the domestic chicken, the world’s most widely eaten bird. Fifty billion are reared annually as a source of meat and eggs. However, on this day in 1975, the population of the city of Haicheng, China, would find themselves grateful to chickens. On 4 February a magnitude 7.5 earthquake struck the city and 2,000 people were killed. However, in the preceding weeks the locals had observed a great deal of strange behaviour among animals. Chickens would run around their coops in panic in the middle of the night and had stopped laying eggs. Cows and horses were restless. Even snakes left their hibernation hideouts and many froze to death. The behaviour was so unusual that the Chinese authorities, who had also noticed odd groundwater events and seismic foreshocks, decided to evacuate the city about 12 hours before the earthquake struck. It is estimated that 150,000 lives were saved following what has been the only successful earthquake prediction in history.

Distributed worldwide in captivity, in the wild it is found in woodland in India and south-east Asia.

5TH FEBRUARY

COMMON HAWK-CUCKOO

Hierococcyx varius

Almost everyone on the Indian subcontinent knows the common hawk-cuckoo, but not by that name. They know it as the notorious ‘brain-fever bird’, or perhaps just as the bird that could conceivably have the most annoying call in the world. It isn’t that the three-note advertisement is inherently untuneful, it is that it is repeated in short cycles, each three-note rendition slightly rising in pitch and sounding, as it continues, concerned, worried, alarmed, desperate, delirious. The sense of anxiety in the rising pitch is palpable.