17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

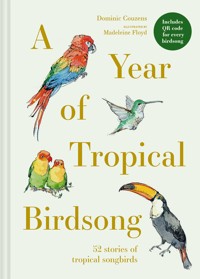

'Whether you are new to wanting to understand birdsong, or are already a fully fledged birdwatcher, this book casts a spell. A truly lovely reading experience' - Love Reading This is a book full of fascinating stories about birdsong for every week of the year, with QR codes to bring each song to life. Leading bird expert and writer, Dominic Couzens, takes you on a journey to enjoy an authentic year of birdsong around the world, one for every week of the year. From the ancient song of the Rifleman that was likely the first sound made by a songbird to the Eurasian Skylark who evokes the zenith of summer, from the constant companion of the American Robin whose song resonates from the top of skyscrapers and complements the howling of a wolfpack in Alaska to the drumming rhythm of the Great Spotted Woodpecker. This book covers a myriad of topics including bird nature and behaviour, stories and literary masterpieces inspired by birdsongs, the musicality of the notes, and what different songs communicate. Each of these fascinating stories are accompanied by illustrations by award-winning artist Madeleine Floyd and a QR code to let you listen to the birdsong while you read. A natural wonder that has captivated and fascinated generations, birdsong is the soundtrack to life. This book offers the perfect tonic whether you are an avid birdwatcher or just want to understand the songs that are often the first thing we hear in the morning and the last thing we hear at night.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 193

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

_________

WEEK 1 Rifleman

WEEK 2 Song thrush

WEEK 3 Great horned owl

WEEK 4 Greater hoopoe-lark

WEEK 5 Common chaffinch

WEEK 6 Eurasian blackbird

WEEK 7 White-throated sparrow

WEEK 8 Great spotted woodpecker

WEEK 9 American robin

WEEK 10 Reed bunting

WEEK 11 Willow warbler

WEEK 12 White-crowned sparrow

WEEK 13 Common nightingale

WEEK 14 Sedge warbler

WEEK 15 Wood thrush

WEEK 16 Common cuckoo

WEEK 17 Marsh wren

WEEK 18 Eastern whip-poor-will

WEEK 19 Red junglefowl

WEEK 20 Chestnut-sided warbler

WEEK 21 Common hawk-cuckoo

WEEK 22 Brown thrasher

WEEK 23 Yellowhammer

WEEK 24 Eurasian nightjar

WEEK 25 Eurasian skylark

WEEK 26 Northern cardinal

WEEK 27 Common snipe

WEEK 28 Northern mockingbird

WEEK 29 Lawrence’s thrush

WEEK 30 White bellbird

WEEK 31 Superb lyrebird

WEEK 32 Common wood pigeon

WEEK 33 Streak-backed oriole

WEEK 34 Eastern towhee

WEEK 35 Laughing kookaburra

WEEK 36 African fish-eagle

WEEK 37 European robin

WEEK 38 Regent honeyeater

WEEK 39 Musician wren

WEEK 40 Australian magpie

WEEK 41 Hwamei

WEEK 42 Tawny owl

WEEK 43 Coppersmith barbet

WEEK 44 Marsh warbler

WEEK 45 Common crane

WEEK 46 White-rumped shama

WEEK 47 Yellow-rumped cacique

WEEK 48 Ring-necked dove

WEEK 49 Common myna

WEEK 50 White-nest swiftlet

WEEK 51 Island canary

WEEK 52 Great tit

Introduction

_________

BIRDSONG IS ONE OF THE JOYS OF LIFE FOR THOSE OF us fortunate enough to be able to hear it. It is also a free gift, requiring no charge to appreciate, although recognizing the species might require the help of a tutor or an app. This gift is offered all around the world. Other than some inhospitable desert and polar regions, and over the open ocean, the sound is everywhere, even in the midst of urban centres. And it is almost universally adored. You rarely hear people saying: ‘I hate the sound of birds singing,’ unless their sleep has been broken at dawn, in which case the birds themselves are quickly forgiven.

The universality of birdsong also extends to the year. While in many parts of the world the zenith of the phenomenon, and the high tide of the dawn chorus, is seasonal, that doesn’t mean that it ceases completely. There are always wild voices out there, even lone ones. A drop in singing in one part of the globe might well coincide with a swelling in another, so while the northern hemisphere birds go quiet in summer and autumn, their counterparts in the southern hemisphere start to warm up. In the tropics the best bird choruses coincide with rainy seasons, when most birds are breeding. So, within these pages we can enjoy an authentic year of birdsong around the world.

This book celebrates 52 memorable bird songs, one for each week of the year. The species and their noises are chosen for many different reasons; not all of the featured voices are even particularly harmonious. Some are chosen because they are apposite to the season, others because they demonstrate an interesting piece of bird song research. Some songs reflect on us, and how we hear and appreciate them. There are stories associated with songs, and literary masterpieces inspired by them. Some songs have an irresistible sense of place.

Although there are birds featured from all over the world, I have chosen mostly from species that are well-known to audiences in Europe and North America. One reason is purely commercial; there might be some wonderful songs from Madagascar, for example, but readers are going to prefer to read about sounds that they know or can imagine hearing. However, the other reason is that most bird song research has been done in these parts of the world, so the most interesting stories and insights, at least until recently, tended to come from here.

The book has been specially written so that any reader can at least get some idea of the actual sound of the bird from a description in words, or even a memory phrase used to identify it. It could be read cover to cover without hearing any of the voices within. However, there is no substitute for actually hearing the songs and calls described, so we have included QR codes. I suggest that you also use a birdsong app (such as Merlin, which covers much of the world) or visit a website such as Xeno-Canto. Many of the songs are on YouTube as well. Most are easy to find online.

Before you read the accounts that follow, it is necessary for me to explain a few very important terms that are used throughout the book, and also to give a brief explanation of what bird vocalizations are actually for. Without these explanations, certain pages might cause puzzlement.

The book is entitled A Year of Birdsong, but not all the sounds featured are, strictly speaking, songs. That’s because birders make a (rather loose) distinction between songs and calls. Part of this distinction is purely descriptive, but a significant amount lies in the biological purpose of the vocalization.

To those of us hearing them, bird SONGS are typically complex vocalizations that last a few seconds at least. They are multisyllabic, and could perhaps be described as sentences, or even paragraphs, depending on the bird. On the other hand, those same species might make different, usually less elaborate vocalizations, which are single words or syllables, or sometimes trills and screams. These are CALLS, or CALL NOTES, which are part of the simpler vocabulary of the bird.

Bird songs are usually seasonal. These more intricate vocalizations rise and fall with the breeding season. In many species, at least part of the song is learned. In the majority of species, especially in temperate parts of the world, they are sung largely, or even only by males. The function of a song is primarily twofold. The male is the main claimer and keeper of a territory, so it sings to other males to keep them away. However, the same (or a different) song is also directed at females, with the intention of attracting their attention and, in a perfect world, eventually mating with them. There are many variations of this theme but understanding its fundamentals will help.

Although most birds, especially those that live in forests or scrubland, sing their songs from a perch, a significant minority perform from the ground, or up in the air, while flying. For the sake of definition, songs which are uttered wholly or usually in flight are known as ‘flight songs’, and the displays in which songs are uttered are known as ‘song flights’.

Calls are used in many contexts and can be very specific, such as those used to incite copulation, or have a broader purpose, such as alarm. They aren’t usually learned, but innate.

The situation is complicated by birds that aren’t strictly songbirds making sounds that are, effectively, a song! Let me explain. Birds are divided into many different groups, by far the largest of which is known as passerines. It’s an unequal divide: more than 60 per cent of the world’s species are sparrow-like passerines, including many of the ones we know best, such as warblers, finches, tits, thrushes and swallows. These passerines are often called perching birds on account of their opposing toe arrangement on the foot, with three facing forwards and one back, allowing for an excellent perching grip. However, passerines are also the world’s main songbirds. This is due to the nature of their sound-producing organ, the syrinx, situated at the bottom of the windpipe, where it divides into the two bronchi (branches) of the lungs. It is much more complicated and advanced than those of other birds – with extra rings, musculature, and so on. The passerine syrinx is a marvel, and much of what makes them special.

However, the lack of a fancy syrinx does not exclude non-passerine birds from defending their territory or attracting a mate by vocalizing. Birds such as cuckoos and doves, for example, obviously do this, often loudly and atmospherically. But they inherit their ‘songs’, and although their voices are often individually distinct and recognizable, they don’t add to them by learning. On the whole, I have tried to call the sounds that they make ADVERTISING CALLS.

There is one more technical matter to describe. Bird song is complex, especially when you listen carefully, and it sometimes needs to be broken down into its constituent parts. For example, birds might repeat a sentence again and again – this is best described as a PHRASE. Within a phrase (or a long monologue) there are often easily distinguished sections, some with several or multiple syllables. These can be called ELEMENTS or STROPHES, the ingredients of the song.

Finally, I will briefly mention a bird sound that is very famous but is not included as itself in the book, and that is the DAWN CHORUS. Clearly, it’s a jumble of voices, but not of a single species. Nevertheless, it is a theme throughout the book. Despite the fact that it occurs around the world, and has drawn much attention, it is poorly understood. Why should birds start singing in the predawn darkness?

There are various hypotheses. Firstly, the transmission of song is often enhanced at dawn, either by atmospheric conditions or the sheer lack of other competing sounds, including human ones. Secondly, dawn song is relatively safe, because night predators are thinking of retiring and the day predators will wait for the light. And thirdly, it’s too dark to find food during the predawn, so it won’t interfere with other activities.

However, these hypotheses cannot explain the full phenomenon, because none of them compel a bird to sing; they just facilitate it. The dawn chorus surely has a compulsion element. One is that, after the night, a bird is wise to protect its territory and mate by reminding everybody that it is still there. Vacancies are noticed immediately and borders soon broken when not defended.

And then there is the effect on the female. The dawn chorus is often at its height, in a particular species, during egg laying, when the female is most fertile; it also peaks at dawn, when a bird has just laid an egg. During this time the male must be vigilant, noisy and impossible for the female to ignore. A male that isn’t singing loudly close by the nest before dawn is likely to find that its mate’s attention wanders elsewhere. A male’s fear of losing its paternity is not the most joyful explanation for the dawn chorus, but it is certainly intriguing!

And song is intriguing. And beautiful, and wonderful; and it lifts the heart. My hope is that, in a small way, this book will do the same.

WEEK 1

Rifleman

_________

Acanthisitta chloris

NEW ZEALAND, 7–9 cm (2¾–3½ in)

IN A BOOK ON SONGBIRDS IT MIGHT SEEM odd to begin with a bird that barely has a song at all. Shouldn’t we start with a bang, a clash of cymbals to lift off the year, or introduce the subject with a soaring, glorious voice that will elevate every heart? What’s the point in listening to the squeak of a rifleman, a midget that lives in the lush southern beech forests of New Zealand? It utters merely a high-pitched ‘seep’ sound, which many people can only hear if they strain their ears.

Why indeed? Well, great things have a habit of starting small and quietly. The best New Year resolutions aren’t the loud promises we make to others, but the silent hopes that are barely whispered.

If you watch the rifleman foraging and calling on a chilly morning on an alpine slope in New Zealand, you might see a diminutive bird, but what you hear is a voice from deep time. Those quiet trills are stirrings. They are close to what was probably the first sound made by any songbird anywhere on Earth, a breath taken as the non-avian dinosaurs breathed their last.

The rifleman is a member of the most ancient living group of songbirds – or at least the most ancient group known from the original songbird lineage, which evolved around 60 million years ago. The rifleman’s family, or New Zealand wrens, are known to have evolved about 55 million years ago, when they branched off from those ancestral forebears. The New Zealand wrens have the simplest sound producing organ, the syrinx, of any songbirds, without any intrinsic muscles, and confined to the trachea. Within the body of the tiny rifleman, and reflected in its breath, is the origin of all the finest bird songs we hear today.

They are close to what was probably the first sound made by any songbird anywhere on earth, a breath taken as the non-avian dinosaurs breathed their last.

Not long ago, scientists assumed that the passerines must have evolved somewhere in the northern hemisphere. However, through DNA sequencing studies and by looking at the palaeogeography of the shifting continents, it is now known this isn’t so. Surprising as it may seem, bird song as we know it began in that part of Gondwanaland that is now Australasia.

That means that every one of our northern hemisphere favourites – larks and warblers, thrushes and nightingales, wrens and mockingbirds, robins and robin-chats, babblers, tits and finches – owes their song prowess to birds that first opened their mouths in that southern region. The dawn chorus, the melodrama of spring, the territorial song flights, the duets, the major soundtrack of the wild – it all began down under.

And, of course, so does our year. The first day of January begins in Oceania and spins westwards. New Zealand is one of the first places to receive the New Year sunlight. And the chances are that, for countless millennia, the quiet calls of the rifleman were among the first species to cast their sounds to the air every year. Small beginnings indeed.

Bird song as we know it began in that part of Gondwanaland that is now Australasia.

WEEK 2

Song thrush

_________

Turdus philomelos

WESTERN EUROPE; FURTHER EAST TO CENTRAL ASIA, 20–23 cm (8–9 in)

IT HAPPENS NOW UNTIL APRIL AT LEAST, without fail. Every year is the same. The gardens of Britain and Northern Europe resound to a sweet-voiced bird song, and everybody is confused.

‘I’ve heard this loud song in my garden,’ says a neighbour. ‘Can you tell me what it might be?’ Another says: ‘I keep getting woken up by this bird singing in the dark and I’ve tried all the bird apps, and still don’t know what it is.’ The answer is always the same. It’s a song thrush. It really is, honestly.

The reason why it confuses people is that listeners just hear a few fragments of a seemingly distinctive song and think it should be obvious what it is. But this is a classic case of information impatience. If everybody just gave the bird a chance to show off its regular singing rhythm, they would find it easy to identify. You just have to give it time.

The song of the song thrush has been described thus in a guidebook: ‘Loud, varied and with a distinct tendency for rhythmic repetition of phrases.’ But far better, and soaked with artistic glamour, are these lines from the poem ‘Home Thoughts from Abroad’, written by English romantic poet Robert Browning in 1845:

That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

The essence of this thrush, then, is that it repeats every phrase (or strophe) several times, in a studied, unhurried fashion. It then moves on to another phrase and repeats that, too, and the next. So you will hear something like: ‘It’s me, it’s me, it’s me! I’m a song thrush, I’m a song thrush, I’m a song thrush! Listen out, listen out! I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here …’. In all, a single song thrush may have more than 200 phrases in its vocabulary, although it will tend to use favourites again and again.

The song thrush’s proclamations are a serenade of earliness, both of the year and the day.

The other characteristics of the song are that it is loud, clear and well-enunciated – all of which means that it’s very easy to notice, breaking out from the running soundtrack of your everyday mind, even when you aren’t a frequent listener to bird song.

Another reason for those January bird song enquiries is that the song thrush’s proclamations are a serenade of earliness, both of the year and the day. It sings at its best during the lightening or the darkening of the sky. It is naturally a bird that feeds in shade, so the predawn and dusk are its comfort zones. In these conditions it is often a lone voice or is sharing the airwaves with the European robin (see here); but it can easily be dominant, so if a sleepy person is opening the curtains or leaving home for the day shift, this is the song that they hear.

There are several intriguing peculiarities about the song thrush and its song. It can start singing as early as November, a couple of months before many resident birds, presumably to establish a territory for the future breeding season. Its peak starts early. Most unusually for any bird, the song thrush also appears to have no visual displays to begin or cement the pair bond. The song is evidently the key. Again unusually, the male stops singing, except at dawn and dusk, as soon as it is paired. Yet another curious behaviour is that in midsummer there is another late resurgence of song, perhaps when young birds can try out their own voices for the first time (see chaffinch, here).

It seems as though even when you know the singer is a song thrush, not all your questions are easily answered.

WEEK 3

Great horned owl

_________

Bubo virginianus

NORTH AMERICA AND SOUTH AMERICA (Outside Amazonia), 46–63 cm (18–24 in)

THE NORTHERN FORESTS ARE IN THE GRIP of winter; nights are desperately cold and seemingly never-ending. The very idea of thriving, let alone surviving, in such conditions would seem almost impossible. But for the great horned owl, that mighty owl of all the Americas, the breeding season is about to begin, even in regions fringing the Arctic.

All through the longest nights, this owl has been sending out its solemn, foghorn-like advertising call, which echoes through forests on still, frosty nights, carrying far. The male doesn’t mince its hoots – one rendition of the five-syllable phrase could be ‘Who … the hell … are … you?’ It doesn’t sound friendly, and it isn’t meant to be; great horned owls are fiercely territorial and will kill persistent intruders.

But the doleful hooting has another purpose, exemplified by the fact that the female great horned owl duets with its mate at this time of the year. Although the female is larger than the male, its voice is higher pitched, and it characteristically adds a few more hoots to its feminine phrase. The male typically starts a bout of duetting, then the female calls, then the male again, and so on; and both sexes sometimes start before the other one has finished. Duetting is, of course, about togetherness. Great horned owls make long-term, and probably lifelong, pair bonds, cocooned in their exclusive territory.

Duetting is, of course, about togetherness. Great horned owls make long-term, and probably lifelong, pair bonds, cocooned in their exclusive territory.

Remarkably, then, now in late January, the female may lay its first egg, although this can happen any time between now and mid-March. The birds are thought to start this early so that the young hatch with enough time to learn hunting skills before next winter kicks in. Even so, conditions can be tough; great horned owls have been found incubating eggs in external temperatures of -30°C (-22°F).

The great horned owl’s hunting skills are remarkable. It sits on an elevated perch in the darkness and waits for something to move below, whereupon it will drop on its target, killing the animal with its talons. These owls take a wide range of prey, mainly mammals, from small rodents to rabbits and hares, as well as birds of all sizes – legend has it that they will kill turkeys. They are famed, of course, for their remarkable vision and hearing, the former being at least three times better than our night vision (which is actually quite good by most standards). Their eyes are packed with super-sensitive rod cells, ideal for contrast in low lighting conditions. Their hearing is undoubtedly superior to ours, the owl depending on its ability to make out the slightest rustle below, which might betray a prey animal. It is a curiosity that a great horned own listens for high-pitched cues such as squeaks and crackles, yet its owl calls are invariably deep. Perhaps the difference is intentional.

The nocturnal habits of owls have long fed the notion that these birds are somehow mysterious, untrustworthy; creatures to be feared. In some parts of the world, they are considered to be spirits and devils, taboo, well worth avoiding. For many years the Apache peoples of North America kept up the tradition of burning down the houses of the departed, so that owls could take their spirits away. It is a deep part of our humanity to fear the dark, so it isn’t surprising that those who inhabit the night should be in league with the shadows.

And yet the magnificent hoot of the great horned owl, calling in the depths of the late winter night, is something very different. It is surely a calling of life, a hastening of the end of the cold. We all delight in those early spring birds, the American robins (see here) on one side of the Atlantic and blackbirds (here) on the other. The shrill vibrancy speaks the promise of spring. Yet the hoots of owls make the same promise earlier. The message might seem sterner, but it is no less optimistic.

WEEK 4

Greater hoopoe-lark

_________

Alaemon alaudipes

NORTH AFRICA; FURTHER EAST TO PAKISTAN AND INDIA, 19–23 cm (7½–9 in)

IF YOU WERE EVER TO SEEK A LIST OF the world’s best bird songs online, you might be surprised to learn that the greater hoopoe-lark is often included among the usual icons such as nightingales and mockingbirds. The hoopoe-lark is a pretty obscure species found in the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East, and further eastwards to the arid areas of Pakistan. Not many people are fortunate enough ever to hear one in person.

There is, of course, a whiff of the romantic about selecting a poorly known bird to appear along with the megastars; the amateur acting alongside Hollywood giants. But there is, of course, no reason to leave out an obscure bird either.