Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: A Day

- Sprache: Englisch

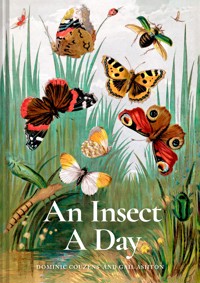

Richly illustrated stories of fascinating insects from across the globe in 366 daily entries. In this beautifully produced collection, nature experts Gail Ashton and Dominic Couzens tell the stories of hundreds of insects with information about behaviour, migration and protection mechanisms, as well as their involvement in folklore, history, literature and more. Learn the scientific name for each bug and why they are important while reading what both poets and scientists have recorded about them over the years. Discover the story of the gnat, whose wings beat at 1000 times a second, the glowworm, who has captured the power of light, and the sacred scarab beetle, worshipped in Egypt thousands of years ago. Illustrated with stunning photographs and works of art, showcasing the colours, textures and strange and unique features of these fascinating creatures, this collection is a celebration of insects and their special place in our ecosystems and culture.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

JANUARY

FEBRUARY

MARCH

APRIL

MAY

JUNE

JULY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

Index

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

INTRODUCTION

Insects are everywhere, all the time, every day of the year. We might not see them on a daily basis, but they are still somewhere. They could be underground, in the sky or anywhere in between. Insects are permanent inhabitants of every continent on Earth. They still haven’t quite figured out the deep oceans, but everywhere else is fair game; insects have filled pretty much every available niche since their ancestors left the seas and made landfall around 480 million years ago. Of course, we are more likely to see them in warmer conditions, especially if we live in more seasonally extreme areas, because most insects are exothermic – requiring warmth and sunshine to function physically and metabolically. In temperate regions, insects will have more defined windows of phenological behaviour; that is, their reproductive and hibernacular cycles are tied to summer and winter respectively. In equatorial and sub-tropical regions, however, where there is little seasonal fluctuation, insects are active most of the year as temperatures and food sources are enduringly more favourable. Go towards the poles and insects spend most of the year in homeostasis, emerging for a period of weeks or even days in the brief windows of weak sunshine and relative warmth. The beauty of these climatic adaptations is that we can see insect activity nearly all the time, whether it be the warm hum of hoverflies in the spring garden, the ladybird snuggling up cosily into a hollowed plant stem in autumn, or the hippity-hop of snow-fleas across frosty moss in midwinter.

Before we commence our year-long odyssey, let’s remind ourselves what an insect actually is. Insects are classified in the kingdom Animalia, and within that the phylum Arthropoda, which is characterized by a segmented body, multiple pairs of jointed legs and a sclerotized (hardened) exoskeleton surrounding a soft body. Insects further distinguish themselves into their own class, Insecta, with a three-sectioned body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed legs and two pairs of wings, putting themselves in a different taxonomic group to similar arthropods, such as spiders and isopods. The subject of wings is something of a grey area, because not all insects have wings, and many appear to have just one pair, the other pair having long ago evolved into something else. The forewings of beetles, for example, have been modified into hard, protective covers beneath which they stow their hindwings. Flies’ hindwings have gone the other way, reducing down into tiny, clubbed stalks that seem useless but have evolved into super-sensitive sensory organs called halteres, which act as gyroscopes and send real-time flight and atmospheric data straight to the pilot’s brain. So, while we can’t always see wings in insects, what we can be sure of is that if it’s small, has wings and isn’t a bird or a bat, it’s definitely an insect.

Thousands of insects depend upon just a single plant species, or a few related species, to survive. The four-barred knapweed gall fly lays its eggs, as its name implies, in the seed heads of knapweeds.

Writing about insects has been, for two entomophiles, the easy part – for who could fail to be interested, intrigued, fascinated or even fixated with this group of animals? The hard part has been choosing which species to include, because the maths involving insects are truly staggering. One in two living creatures on Earth is an insect and they make up 90 per cent of all known animal species. The number of known global insect species currently sits at around 1 million, and it is possible that we are barely scratching the surface. Estimates fluctuate wildly between 2 and 30 million insect species on Earth right now, and that doesn’t include the many species that are becoming extinct before we’ve even discovered them. According to the Royal Entomological Society, there are around 1.4 billion insects per human on Earth; their mass outweighs humans 70 times. Other sources estimate that there could be 10 quintillion individual living insects on Earth as you read this – that’s a ten with 18 zeros on the end of it. We still don’t even talk about money or data in these terms: humans are lagging way behind with mere billions and trillions as a measure of hugeness. Social wasp nests can house tens of thousands of individuals, and termite mounds, hundreds of thousands. So how can our planet house so many insects when we humans are struggling to balance the ecological scales with a global population of 8 billion?

The sheer number of species of insects is remarkable. The elephant hawk-moth Deilephila elpenor is one of 1,450 species in its family Sphingidae, and one of 160,000 species of the order Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths.

It comes down to size. We tend to measure success on scale – bigger is better and all that – but the foundations of this theory become very shaky when insects are brought into the picture. Insects used to be a lot bigger; take, for example, the gargantuan Meganisoptera of the late Carboniferous period, when atmospheric oxygen levels exceeded 20 per cent. These giant, dragonfly-like beasts had wingspans of 0.5m (½ft) and would give modern-day birds of prey a run for their money. This proved to be an unsustainable body plan, however, as a series of cataclysmic climate events and decreasing atmospheric oxygen levels wiped out the majority of species on Earth. The largest insects were pushing the limits of a successful body plan anyway (the rules of insect biomechanics can only go so far), so over hundreds of millions of years they became smaller, needing less food, water, free oxygen and space to survive. Combined with their short life span and prolific reproductive rate, which allow for rapid adaptation, insects have processed along a wildly successful avenue of evolution that brings us to the modern day, with an almost unquantifiable global population of insects, the diversity and variety of which is truly staggering.

It is so incredibly sad, then, that instead of admiring the success of the insects of Earth, we choose to demonize them. In the very short span of history that humans have occupied the planet (around 2 million years, a little shorter than the near 400-million-year occupation of insects), we have put our six-legged roommates in Room 101, the sin bin, the bad books. We blame them for everything from itchy skin to global food shortages, and our self-styled solution has been to kill them. It is our absolute conviction they are The Enemy, and thus we spend a disproportionate quantity of our time and resources obliterating them from existence, and this is a huge problem. We swat, spray, splat and squash them without really thinking about the consequences of this wholesale insecticide, because we only see the short-term benefits of having fewer insects bothering us. But learn more about insects, and look closely at them, and the veil of disgust will quickly fall away to be replaced with fascination, respect and yes, even affection. Because insects are beautiful! They are fluffy and have big eyes and they often look at you quizzically – they are basically tiny puppies. And many will sit happily on your hand; they can be very good company. They are superb parents, laying their eggs strategically, cleaning and tending their young and protecting them from harm, just like we do. And relatively, they don’t bother us at all. For every delirious, hypoglycaemic wasp that panics in our terrifying presence and stings us, and every fiercely determined female mosquito who desperately needs to catalyze her egg production with a blood meal, there are literally millions of other insects that never come near us and have no desire to do so, they just want to get through the day. Sound familiar?

Most of the species in this book will never cross paths with each other, or even be aware of each other’s existence, but they all share a strong bond, because they are all part of an expansive and intricate web of life, in which every individual insect plays a critical role. It may become food for something else; it may inadvertently assist in driving global food production through pollination services; it could be one of the recycling team that processes matter into soil nutrients, before its own body ends up as particles of loamy, nutritious compost. It might be one of a legion of predatory or parasitic insects, which naturally suppress population explosions, and scaffold food security within agricultural systems. It could even be one whose toxic biochemistry is being synthesized into the new generation of cancer-killing drugs. Every one of these roles is minor, but together they have formed the glorious, diverse, stable, habitable planet upon which we live today. I don’t know about you, but I think that deserves respect and kindness, rather than a fly swatter or the sole of a shoe.

It is with delight and pride that we present to you 366 insects and stories of insect folklore; one for every day of the Gregorian year – including that quadrennial leap day that offers us an extra 24-hour window and – in this book – a bonus opportunity to meet another incredible insect. Our selection contains six-legged ambassadors from all over the globe, all with astonishing adaptations. You will meet a ghostly butterfly that haunts the permanent twilight in the darkest recesses of the tropical rainforests and encounter a surprisingly resilient moth in the frozen Arctic depths. We also dive into the rich cultural fabric that binds us to insects through history via myth, legend and fossil record. If that hasn’t piqued your interest, how about a beetle that can conjure its own water supply from the air in the hottest, driest deserts, and even an insect that has conquered the surface of the ocean? You will read about residents from your own doorstep that you know very well and be introduced to fascinating new species from far-away places. We want you close this book at the end of the year with a new perspective on insects; an increased sense of empathy towards them, an understanding of their place in the world, or maybe even the resolve to go out and discover these extraordinary beasts in the wild. If we can spread our love of this marvellous group of animals further into the world, then we will be very happy.

DOMINIC COUZENS and GAIL ASHTON, 2024

The lacewing is just one example of the extraordinary evolutionary paths that insects have taken over the last 480 million years.

1ST JANUARY

THE FLY

It isn’t easy for us humans to imagine life through the eyes of an animal the size of a fly. Conversely, the human world is so large that it is almost imperceivable to the micro-verse. And yet, here we are, co-habiting this planet in our very different ways…

How large unto the tiny fly

Must little things appear! –

A rosebud like a feather bed,

Its prickle like a spear;

A dewdrop like a looking-glass,

A hair like golden wire;

The smallest grain of mustard-seed

As fierce as coals of fire;

A loaf of bread, a lofty hill;

A wasp, a cruel leopard;

And specks of salt as bright to see

As lambkins to a shepherd.

WALTER DE LA MARE (1873–1956)

A negative image of a housefly.

2ND JANUARY

VAMPIRE MOTHS

Calyptra spp. | Lepidoptera / Erebidae

No matter how much we learn about the extraordinary diversity of the insect world, it is still capable of delivering the most unlikely surprises. Within a group of insects that are almost exclusively vegetarian, there is a moth that has thrown the rule book out of the window. Calyptra – numbering less than 20 species – is the only known genus of moth that drinks blood and, even more strange, it is only the males that are sanguivorous. This is highly unusual, as it is usually females that require blood meals in order to activate the development of their eggs, and it is unknown if males synthesize blood for reproductive purposes. Both sexes have a piercing proboscis; males can pierce the skin of large mammals, whereas females appear to stick to sucking the liquid from soft fruit.

Only the males drink blood, the females prefer soft fruit.

3RD JANUARY

GREAT DIVING BEETLE

Dytiscus marginalis | Coleoptera / Dytiscidae

In temperate regions there are slim pickings for finding adult insects in the middle of winter, but freshwater is still excellent, and one of its most impressive inhabitants is the great diving beetle. Sometimes you can spot it through the ice on ponds. This beetle has long, oar-like hind legs, which are flattened and fringed with hairs to help it move through the water. To breathe, it holds an air bubble on its ventral surface. It is a voracious predator in both the adult and larval stage, and it is perfectly capable of eating fish, frogs and newts. It can also fly from pond to pond, always at night.

The great diving beetle of Europe and Asia can grow to 35mm long.

4TH JANUARY

FOSSILIZED WASP

Palaeovespa florissantia | Hymenoptera / Vespidae

Apicture of a wasp is rendered on a rock. It is exquisitely detailed, such as the impression a screen print or photogram could leave behind. Every abdominal segment is marked out; thoracic marks, even the thinnest veins on the wings are present. But this isn’t a picture, it is a fossil. The Florissant Fossil Beds of Colorado, USA, house one of the richest arthropod fossil reserves yet discovered on Earth. The fossil beds are shales formed around 34-44 million years ago, resulting in layers of fossilized organisms, including this beautifully preserved palaeovespa florissantia, a direct ancestor of modern hornets and social wasps. This and other wasps were living socially, in colonies, as they still do, and nectaring on flowers that must have been present in the area. Fossils such as this are an extraordinary snapshot of a time otherwise unrecorded, helping us to piece together how the world looked so many years ago.

This image is not a painting, but one of the earliest known fossilized impressions of a social wasp, dated to around 40 million years ago.

5TH JANUARY

ORCHID MANTIS

Hymenopus coronatus | Mantodea / Hymenopodidae

The mantids are famous for their striking prayer posture, and for incidences of post-coital mariticide. Mantids use camouflage to hunt, and many species are slender and green, blending into vegetation. However, the flower mantises have evolved to mimic inflorescences. The orchid mantis is pearly white with subtle markings, and its back two pairs of legs are modified to look like the petals of orchids. Although it appears to just mimic the orchid’s appearance, its success could be down to more complex factors. Smelling like, and copying the UV markers of, an orchid may also be at play in the mantis’ strategy for luring its prey – so much so that controlled experiments have found that the mantis is actually more attractive than its floral counterparts!

Not only does this mantis look like an orchid, it smells like one too!

6TH JANUARY

SILVERFISH

Lepisma saccharinumZygentoma / Lepismatidae

If you’ve ever glimpsed a silverfish scuttling away when you switch on the light in your kitchen, you have looked through a window into the distant past. The silverfish is a small, flightless insect that closely resembles those that dominated in the Silurian period 420 million years ago, before they developed wings. It is thus a throwback, and a survivor.

The Silverfish is the living fossil in your kitchen.

7TH JANUARY

HUMP EARWIG

Anechura harmandiDermaptera / Forficulidae

Mothers the world over are famous for the sacrifices they make for their offspring, and they number insects among them. Few make the sacrifice quite as fully as the hump earwig, however. This insect breeds in the winter, which is great for avoiding predation, but not so good for gathering provisions to feed the growing nymphs. The answer is known as matriphagy – the offspring kill and eat the mother.

The hump earwig makes a bigger sacrifice than most.

8TH JANUARY

FAIRY WASP

Dicopomorpha echmepterygis | Hymenoptera / Mymaridae

Size matters. Or does it? In a world where bigger is better, let’s ponder the fact that the extraordinary evolutionary success of insects is largely (no pun intended) due to their size. Being small is a great survival model, but just how far can you physically take that? The smallest insect currently known, dicopomorpha echmepterygis, is a wasp that occupies less space than an amoeba. It is about as small as we think functional multicellular life can possibly get. The blind, wingless males measure around 140µm, less than the width of a human hair. The comparatively gargantuan females, at around 200µm, are still so small that their wings do not require a membranous surface. At this scale, air moves more like liquid and the wasp can be propelled along, aided merely by thin paddles fringed with long, delicate hairs. If you haven’t heard of these micro-beasts, it isn’t because they are rare. On the contrary, they are everywhere; but their near-impossible size means that we just don’t see them.

The fairy wasp is the smallest insect you can encounter.

9TH JANUARY

GOLDENROD GALL-FLY

Eurosta solidaginis | Diptera / Tephritidae

It’s remarkable how many small and seemingly unexciting insects have extraordinary talents. In the case of the goldenrod gall-fly, it’s the larvae – they are incredibly hardy, being among the very few insects that are cold tolerant, allowing ice to form in their tissues. The larvae live in galls on the goldenrod plant (Solidago spp.). Their tissues contain glycerol and other cryoprotectants, which means that they don’t freeze until it is at least –20°C (–4°F). But they can cope beyond that, their body allowing ice to form in the gaps between cells. These animals have ice in their veins – and mild winter temperatures can be fatal to them.

Goldenrod gall-fly larvae can survive partial freezing in the depths of winter.

10TH JANUARY

ARMY ANT

Eciton burchellii | Hymenoptera / Formicidae

Two hundred thousand ants on the move makes for an intimidating sight. The ground seethes with them as they march in living tributaries across the forest floor, searching for any living thing of the right size to feed their growing larvae back at the colony. During a 12-hour raid, the columns, some 200m (650ft) long, may kill as many as 100,000 other animals as they sweep across an area, leaving the ground bereft of life. The next day, they will do it again. Each night, the ants make a bivouac of nothing more than living bodies, held together with hooks on the workers’ feet, in a different place each night.

The daily raids happen during the ant colony’s ‘nomadic phase’, when the eggs have hatched and the larvae are always hungry. After 15 days, the colony enters a ‘statary phase’, when the queen is in egg-laying mode, and the raids are only once every other day. During this phase, they ants may bivouac in the same place on consecutive nights.

Army ants must carry their larvae across the forest floor when relocating.

11TH JANUARY

TIMBER FLIES

Pantophthalmus spp.Diptera / Pantophthalmidae

Timber flies of Central and South America are enigmatic, gentle giants that almost rival the Mydas flies in length and wingspan. Females lay eggs in trees or deadwood. The larvae develop in galleries within the wood; their diet is something of a mystery – possibly fermenting sap or the wood itself. They aren’t quiet about it either, and can be heard munching away inside the tree from metres away.

Timber flies are gentle giants, and superbly coloured, with bright yellow wings.

12TH JANUARY

CLEARWING

Greta otoLepidoptera / Nymphalidae

Common clearwing butterfly wings have two distinctive scale structures. The clear area has waxy, anti-reflective properties and sparse, hair-like scales that transmit light. The coloured parts have densely packed, tooth-shaped scales that not only block and reflect light, but also prevent the wings sticking together. The result is a living trompe-l’oeil in the forests of Central America.

These butterflies have complex wing structures that help them camouflage in the dappled rainforest sunlight.

13TH JANUARY

ARCTIC TERN LOUSE

Quadraceps houri | Psocodea / Philopteridae

What’s the world’s best-travelled insect? The answer is almost certainly an insect that cannot actually fly. If you discount headlice, which could be attached to well-travelled humans (even astronauts!), then the lice or fleas of birds would be good candidates.

One strong possibility is a parasite attached to a long-distance migrant, such as the Arctic tern (sterna paradisaea). Quadraceps houri is an example, which uses hosts of several bird species. The Arctic tern flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic in autumn and back again in spring, and may cover 80,000km (50,000 mi) a year. The average bird louse lives about one month, so that could still be quite a ride!

The much-travelled Arctic tern carries passengers with it.

14TH JANUARY

LEAFCUTTER ANT

Atta spp. | Hymenoptera / Formicidae

By the time humans even thought about cultivation and farming, the leafcutter ants of South America already had a long-established, highly successful system of agriculture that still exists today. Over 200 species of leafcutter ants have developed a mutualistic relationship with fungi, which they grow and harvest within their nest for food. You’ve probably seen documentary footage of lines of ants carrying sections of leaf in convoy across the forest floor. Perhaps surprisingly, the ants don’t eat the leaves themselves; back in the nest, they chop up the leaves and spread them over the subterranean fungal threads called hyphae. The hyphae ingest the leaves and are themselves eaten by the ants. But why go to all that effort, when the ants could simply eat the leaves? The plant material contains polymers that the ants cannot metabolize, meaning they cannot access all of the nutrients within. However, the fungi can break down those polymers, and by eating the fungi the ants gain significantly more nutrients. This mutualistic relationship has been happening for so long that the cultivated fungi found in ant nests cannot be found anywhere else in the wild; so specialized is it that a newly emerged queen will take a ‘cutting’ of her nest’s hyphae with her when she leaves to begin her own colony.

Humans don’t have a monopoly on farming; leafcutter ants cultivate fungal hyphae as food for themselves.

15TH JANUARY

WESTERN HONEYBEE

Apis mellifera mellifera | Hymenoptera / Apidae

We celebrate the honeybee today, clever insect extraordinaire. In recent years, scientists have unearthed abilities and attributes that, until recently, would have seemed inconceivable for an insect with a tiny brain of only 1 million neurons (by comparison we have 100 billion). Who, for example, would ever have predicted that an insect could count? But they can, to four (it takes humans at least 10 months to acquire this ability). Recent research even suggests that they can do simple sums. They can also remember the colours and shapes of flowers for several days (but they cannot see red colours). They can work out complex tasks such as lifting lids to get food. They can also pass on instructions to other bees and, in turn, learn how to do things by watching demonstrations.

Honeybees are not little robots, but have distinct personalities, with individual strengths and faults. Some are not as effective at the tasks they are meant to perform as others. Some, you may be delighted to hear, just aren’t that good at housework!

It may come as a surprise that the honeybee has the ability to count.

16TH JANUARY

AN ABUNDANCEOF BEETLES

Coleoptera

With at least 350,000 described species, the order Coleoptera outranks every other known group of animals on the planet. One in four of every described species of anything is a beetle, and a group of beetles, the weevils (Curculionoidea), contain more living species (80,000) than all birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish put together.

‘The Creator, if he exists, must have an inordinate fondness for beetles.’

J. B. HALDANE

‘Whenever I hear of the capture of rare beetles, I feel like an old war-horse at the sound of a trumpet.’

CHARLES DARWIN

‘It seems therefore that a taste for collecting beetles is some indication of future success in life.’

CHARLES DARWIN

The beetle body blueprint is one of the most successful on Earth.

17TH JANUARY

UPSIDE-DOWN FLY

Neurochaeta inversaDiptera / Neurochaetidae

With a name like that, these flies simply have to occur in Australia, don’t they? Only discovered in the 1960s, they are now also known to be from New Guinea, Malaysia and Africa. They have a very strange habit of always clinging on to a vertical surface with their head pointing down. If you put them in a container and turn it upside down, all the flies reorientate to face down. Whatever direction they go, even sideways, the head stays down. If they ascend, they walk backwards.

The only way to get these flies facing sideways is to pin them!

18TH JANUARY

ICE CRAWLERS

Grylloblattodea / Grylloblattidae

The frozen Arctic is home to some highly specialized insect species, including the ice crawlers. A rather unique group of insects, they look like a mixture of termite, cricket and cockroach. Ice crawlers endure almost constantly freezing temperatures in the Arctic Circle, living in ice caves or underground, feeding on any dead organic matter they can find. Their unusually slow metabolism means that they can also live much longer than many insects – up to ten years.

The ice crawlers have adapted to the harshest conditions on Earth, surviving at temperatures that are almost permanently sub-zero.

19TH JANUARY

BLUSHING PHANTOM

Cithaerias pireta | Lepidoptera / Nymphalidae

Butterflies are well known for their habit of flying in the daytime and loving warm, sunny weather, in contrast to their relatives, the moths, which are generally nocturnal. Nature does, however, like to bend the rules. We have moths that fly by day, and there are also butterflies that like the dark. The Haeterini are a tribe of butterflies, including the blushing phantom, that live in the dense understory of the Amazon rainforest. They negotiate their way through the gloom in a leisurely fashion, feeding on rotting fruit and fungi. These elusive butterflies are not easy to find in the almost permanent twilight between forest floor and canopy, and they emerge at dusk, possibly to avoid diurnal predators. Their inconspicuous behaviour is compounded further by their morphology: Haeterini wings are a delicate mix of pigment, structural colour and translucency, the result of which is a diaphanous film which reduces them to mere phantoms in the shadows.

The blushing phantom lives a twilight existence in the shadowy rainforest understorey.

20TH JANUARY

SALTPOOL MOSQUITO

Opifex fuscus | Diptera / Culicidae

This mosquito is endemic to New Zealand, where it lives by the ocean inhabiting coastal rockpools and intertidal margins (only about 5% of mosquito species live in this type of habitat). Eggs are laid above the waterline and are washed into rockpools where they overwinter; the emerging larvae are omnivorous, eating small invertebrates and tidal sediments. Saltpool mosquitoes are highly unusual in that adult females do not need to ingest blood for their eggs to start developing.

The saltpool mosquito lives in rock pools on New Zealand’s coast.

21ST JANUARY

GLOWING CLICK BEETLE

Deilelater physoderus | Coleoptera / Elateridae

As if click beetles aren’t fabulous enough, with their nifty, spring-loaded hingelock system that propels them through the air with a G-force that can exceed 300, some of them have their own headlights, too! The glowing click beetles of the American tropics are bioluminescent. The back corners of the pronotum shine brightly with the presence of oxygen, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and the bioluminescent enzyme luciferin, which, when combined, produce a light that is bright enough to be seen at some considerable distance, which has has earned them the nickname ‘headlight elaters’. They can even control the intensity of the light with an in-built ‘dimmer switch’.

The glowing click beetle can produce a bioluminescence so bright that it looks like it is equipped with headlights.

22ND JANUARY

MILICHID FLIES

Phyllomyza spp. | Diptera / Milichiidae

‘Will you walk into my parlour?’ said a spider to a fly;

‘’Tis the prettiest little parlour that ever you did spy.

The way into my parlour is up a winding stair,

And I have many pretty things to shew when you are there.’

‘Don’t mind if I do,’ said Phyllomyza, ‘kind of you to ask.

‘It happens that I’m sitting here and ready for the task.

‘You cannot see me, I’m too small, my body you can’t feel,

‘But when you’ve wrapped the struggling prey, my purpose I’ll reveal.’

‘When work is done, when enzymes sweet have bodily digested,

‘The fly right here, whose sad demise your silken web invested,

‘I’ll play my hand and drink some juice, I only need the dregs,

‘And when I’m full I’ll leave, unseen, to go and lay my eggs.’

ADAPTED FROM THE POEM ‘THE SPIDER AND THE FLY’ BY MARY HOWITT (1799–1888)

The Milichid fly’s small size gives it unusual feeding opportunities.

23RD JANUARY

WINGS

Apart from birds and bats (and prehistorically the pterosaurs), insects are the only group of animals on Earth capable of flight. No other animals have successfully evolved parts of their bodies into appendages that can carry their body weight through the air for long periods. The possession of wings gives insects an enormous advantage in the game of life, as flight allows you to travel greater distances to find food and potential partners. A further contribution to success are the different ways in which insect wings have adapted over millions of years, creating distinct groups. In flies, for example, the hindwings have been reduced to small appendages that act as flight stabilizers, leaving the forewings for actual flight. The beetles have adapted their forewings into hardened casings – often colourful or patterned – that conceal the flying wings. And wings aren’t only used for flight; they can also be a powerful communicator during courtship displays, or to establish territory.

Insect wings have evolved over hundreds of millions of years into vastly diverse structures that suit many different lifestyles and purposes.

24TH JANUARY

GLITTER WEEVILS

Pachyrhynchus spp. | Coleoptera / Curculionidae

These spectacular, glittery weevils have to be seen to be believed; they’re part beetle, part kid’s art project!

Sometimes an insect comes along that just doesn’t seem real. The almost ubiquitous usage of image manipulation and AI can have us doubting whether what we have seen can possibly be genuine. This can particularly be the case for many insects, some of which appear in this book and prove that fact is truly stranger than fiction. And then there is the glitter weevil. It doesn’t look like the pinnacle of photoshop though; it looks like a child stuck sequins all over the family dog. This weevil has a rich, black cuticle that is adorned with the most spectacular, tiny iridescent scales. It is the sort of experimental crafting that may initially bring out the cynic in you, and have you wondering what random turns evolution felt the need to take to end up with a miniature disco pug. But once the disbelief has diminished, you will realize that this is not a TikTok prank, but a genuine animal better than anything the human imagination could concoct.

25TH JANUARY

METALLIC STAG BEETLE

Cyclommatus metallifer | Coleoptera / Lucanidae

There are impressive stag beetles in Europe and the USA, but for sheer star quality, both are outshone by this extraordinary beetle from Indonesia. It comes in two colour forms, gold (which is the most common) and black, which naturally arise in both wild and captive populations. The males bear the outsized mandibles, which are used in combat over females. Well-matched males indulge in gladiatorial combat, jostling with their mandibles and trying to bite one another, with an end game of throwing your rival off the log or branch on which you are competing.

This is the gold form of the extraordinary metallic stag beetle.

26TH JANUARY

LEAF-ROLLER FLY

Trigonospila brevifacies | Diptera / Tachinidae

Parasitic flies may not sound particularly endearing to most people, but here’s one that surely cannot fail to charm. The leaf-roller flies (trigonospila spp.), found in Australia and New Zealand, are snazzily striped species with crisp black and white (or pearly) horizontal bands, making them look like tiny, walking pedestrian crossings. These enigmatic flies are thought to parasitize leaf beetles (chrysomelidae) and for this reason are seen as beneficial biological control.

The leafroller fly is a super-smart fly native to Australia and New Zealand.

27TH JANUARY

SPUR-LEGGED STICK INSECT

Didymuria violescensPhasmatodea / Phasmatidae

This is a common species of stick insect, which, bearing in mind it lives in Australia, has made the very sensible career move to feed on the leaves of eucalyptus. As these are the dominant local trees, numbers of this phasmid can easily build up to almost plague-like proportions, and they can defoliate entire forests. Strangely, the more abundant they get, the more colourful they become, seemingly abandoning their usual green and brown camouflaging colours. The flying males, in particular, can be gorgeous with their startling violet wings.

This stick insect shows off impressive colours in flight.

28TH JANUARY

MEALWORM BEETLE

Tenebrio molitor | Coleoptera / Tenebrionidae

Did you know the mealworms you leave out for your garden birds are actually a beetle? Mealworm beetle larvae are bred in farms, then dehydrated and packaged into a wide variety of animal feed, including bird feed. They have a high percentage of protein relative to their mass, making them extremely energy efficient to both produce and to eat. They require less water, space and food, and produce less CO2 per kg of bodyweight than cattle or similar livestock. The European Food Safety Authority recently classified mealworms as safe for human consumption, and around the world they are already an integral part of our diet. Ground-up mealworms are made into a protein powder that can be incorporated into everything from milkshakes to burgers. These beetle larvae are likely to become a standard Western ingredient on a par with large mammal livestock and could be the key to our planet’s food security.

Beetles and other insects are already intrinsic to the diet of many countries and could be the key to future global food security.

29TH JANUARY

DANCING JEWEL

Platycypha caligata | Odonata / Chlorocyphidae

Damselflies, those high-viz insects that live in a world of dazzling colours, go in for some pretty fervent, highly charged courtship. In the case of the dancing jewel, there is more leg-showing than a tango. The male is adorned with a fancy livery, with a shining, powder-blue abdomen, plus crimson below the abdomen, and long legs with an eye-catching combination of red and brilliant white. As soon as a female approaches, the male flashes his white tibiae, then flies around the female and waves his blue abdomen, without subtlety. If the potential mate remains in place, the zenith of the display is to hover in front of her, shivering the white parts of the legs until they are a blur.

It’s the white flashes on the legs of the male dancing jewel that catch a female’s attention.

30TH JANUARY

HONEY ANT

Camponotus inflatus | Hymenoptera / Formicidae

In the Australian desert, where water and food are scarce, a group of ants has taken matters into their own hands, literally turning themselves into a food store for the rest of the colony. Honey ant colonies contain a section of workers that have incredibly elastic abdomens, within which a rich, sugar-rich liquid is stored. These workers hang from the ceiling of the nest while provisions of honeydew are delivered and fed to them by foraging sisters. When fed, the abdomens of these ‘living larders’ distend to huge proportions, bursting with sugary liquid. They remain in place like little vending machines, regurgitating their honey stores, as required, to feed the colony in lean times. Foraged by Indigenous people for generations, their ‘ant honey’ is recognized as having antimicrobial properties, the applications of which are already used by communities to heal wounds and soothe throat infections – yet another way in which insects are beneficial to humans.

Honey ants have evolved a novel way to ensure year-round food availability, by turning part of their workforce into a living larder.

31ST JANUARY

SOCIAL WASP

Polybia paulista | Hymenoptera / Vespidae

It’s safe to say that humans aren’t keen on being stung by wasps. The venom delivered into the skin, depending on the wasp, can register anywhere from mild annoyance to blinding pain. Polybia paulista is a social wasp that is endemic to south-east Brazil. It is one such wasp capable of administering a painful injection when feeling particularly threatened itself, or on behalf of its nest colony. But the venom of this wasp contains something else that we have discovered is far more beneficial. Polybia paulista contains a peptide that has been named Polybia-MP1 (MP1 for short) and is capable of selectively killing some cancer cells. This wasp is just one example of how our problematic relationship with insects may actually be causing us more harm in the long term. We can potentially unlock the key to many more medical breakthroughs, if we focus our efforts on conserving and understanding insects that pose a risk to us, rather than seeking to eliminate them.

Far from being our enemy, this social wasp (Polybia paulista) could in fact save many of us in the fight against certain cancers.