Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

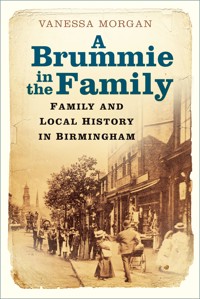

Family history is one of the most popular hobbies of recent years, with many looking into their roots and finding out about their past. In this book you will learn how to find dates and events in your ancestors' lives, and it will help put flesh on the skeletons too, giving clear instructions of how to start researching your family history in Birmingham. You will then begin to learn the full story of how Birmingham grew and how our 'Brummie' ancestors lived, played and worked. This book is not just a 'how to' book, but also tells the story of how Birmingham expanded during the nineteenth century, as our ancestors moved here to find work in the new industries. Some lived in the cramped conditions of back-to-back housing, whilst others prospered and joined the ranks of the more well-to-do. Not just the wealthy, but the poor, too, all played their part in the development of this now-sprawling city.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Brummiein theFamily

Family and Local History in Birmingham

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Vanessa Morgan, 2021

The right of Vanessa Morgan to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9756 0

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Some fifty-odd years ago Dodds, a local comedian, used to sing:

‘Brumagen has altered so,

There’s scarce a place in it I know

Round the town you now must go

To find old Brumagem.’

Had he lived till these days he might well have sung so, for improvements are being carried out so rapidly now that in another generation it is likely old Birmingham will have been improved off the face of the earth altogether.

Showell’s Dictionary of Birmingham (1885)

Old Square. Once found on the corner of Bull Street with Upper and Lower Priory, Old Square was swallowed up by the development of Corporation Street. (Author’s Collection)

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 Birmingham – a History in its Making

2 Researching your Birmingham Roots

The 1939 Register

The Census

Births, Marriages and Deaths

Parish Registers

Bishop’s Transcripts

Nonconformist Records

Using the Internet

The Library of Birmingham

3 Expanding your Roots

The Parish Chest

Vestry Meeting Minutes

Settlement and Removals

Apprenticeship Indentures

Bastardy Bonds

Overseers’ Accounts

Churchwardens’ Accounts

The Workhouse and the Poor Law Unions

Newspapers

Court Records

Cemeteries

Wills and Probates

Directories

Electoral Registers

Land Tax Assessments

Hearth Tax

Enclosure Awards

Tithe Maps and Apportionments

School Log Books

Rate and Rent Books

Manorial Records

Military and Police Records

4 Compiling and Writing your Family History

5 Working in Birmingham

6 Life in Birmingham

7 Around Birmingham and its Suburbs

Aston

Saltley

Erdington

Sutton Coldfield

Castle Bromwich

Yardley

Sheldon

Acocks Green

Hall Green

Balsall Heath

Moseley

Kings Heath

Selly Oak

Bournville

King’s Norton

Northfield

Edgbaston

Harborne

Quinton

Handsworth

Great Barr and Perry Barr

Acknowledgements

To tell the story of Birmingham I have found it, in places, more appropriate to use quotes from archival books written many years ago. In that way I am letting the people of the time tell their own story and showing what Birmingham was really like at the time.

One such writer, John Langford, explained in his A Century of Birmingham Life that he felt it ‘would be more interesting and useful to let our forefathers speak for themselves, than tell their story in other words’. So that is exactly what I have decided to do when describing some of the people and certain parts of the history of Birmingham.

Although there is a large section on ‘How to do your Family History’, this book is also very much a local history book, which will help you put flesh on the bones of your Brummie ancestors. Hopefully it will show who they were, what they did and how they lived.

So I would like to acknowledge the following that have been invaluable research tools for this book:

History of Birmingham by William Hutton (1783), plus various later editions including the updated version by James Guest, 1836.

A Description of Modern Birmingham by Charles Pye, 1818.

Pigot’s Directory, 1841.

Birmingham: History and General Directory of the Borough of Birmingham by Francis White & Co., 1849.

A Century of Birmingham Life (1741–1841) by John Alfred Langford, 1868.

Kelly’s Directory, 1872.

Personal Recollections of Birmingham and Birmingham Men, edited from pieces taken from the Birmingham Daily Mail signed S.D.R. and published by E. Edwards, 1877.

Showell’s Dictionary of Birmingham by Thomas T. Harman and Walter Showell, 1885.

A Tale of One City: The New Birmingham by Thomas Anderton, 1900.

Victoria County History, first published 1901.

I would also like to acknowledge those who contacted me through social media, namely Chris Lea, Ivor Roth, John Sullivan and Peter Jones.

I

Birmingham – a History in its Making

What and who is a Brummie, and where did the name come from?

‘Brummie’ is an affectionate term used to describe someone who lives in or originated from Birmingham. But why the term Brummie? Throughout time, Birmingham has been recorded with many variations – Brumwycham, Bermyngeham, Bermicham, Bromwycham, Burmyngham, Byrmyngham and Birmingham. But the one name that stuck is Brummagem. This name dates back many centuries and is thought to have derived from a name still being used in the seventeenth century, Bromicham. It should be noted that the word ‘Bromwich’ is prominent in this part of the Midlands, with other towns such as Castle Bromwich and West Bromwich.

In A History of Birmingham, William Hutton tells us that the ‘original seems to have been Bromwych: Brom, perhaps, from broom, a shrub, for the growth of which the soil is extremely favourable: Whych, a descent; this exactly corresponds with the declivity from the High Street to Digbeth.’ Others say the ‘ham’, being the Saxon word for home, was then added and therefore translating the name as ‘home on the descent on which broom grows’.

However, Charles Pye tells us in A Century of Birmingham Life, that ‘the derivation of the word Birmingham has been the source of considerable controversy; and has afforded “gentle dullness” one of its favourite occupations.’ He also quotes from a piece written in September 1855 by John Freeman in a magazine, the Athenaeum:

The word Birmingham is so thoroughly Saxon in its construction that nothing short of positive historical evidence would warrant us in assigning any other than a Saxon origin to it. The final syllable, ham, means a home or residence, and Bermingas would be a patronymic or family name, meaning the Berms (from Berm, a man’s name, and ing or iung, the young, progeny, race, or tribe). The word, dissected in this manner, would signify the home or residence of the Berms; and there can be little question that this is its true meaning.

Other sources refer to the word Brummagen as being a variant to the name, or the way it was said, which appeared locally in the early 1600s. However long ago and how it first started the name has certainly retained its charm right into the twentieth century and beyond as even today Birmingham is still fondly known as Brummagen, or Brum for short.

It may seem incredible now but William Hutton tells us that Birmingham in 1783 was the smallest parish in the district. The largest was King’s Norton, being eight times larger than Birmingham. Aston and Sutton were five times larger and Yardley, four times larger. He talked of the springs in Digbeth being so plentiful they could supply the city of London. But in reprinting the book in 1836, James Guest said he was ill-informed, that the springs often dried up and the water from the pumps was hard and not suitable for washing.

From the pages of his book, Hutton takes us on a walk around historic Birmingham as he asks us to:

perambulate the parish from the bottom of Digbeth, thirty yards north of the bridge. We will proceed south-west up the bed of the old river, with Deritend, in the parish of Aston, on our left. Before we come to the flood-gates, near Vaughton’s Hole, we pass by the Longmores, a small part of King’s Norton. Crossing the river Rea, we enter the vestiges of a small rivulet, yet visible, though the stream has been turned, perhaps a thousand years, to supply the moat.

At the top of the first meadow from the river Rea, we meet the little stream above mentioned, in the pursuit of which, we cross the Bromsgrove Road, a little east of the first mile stone. Leaving Banner’s Marlpit to the left, we proceed up a narrow lane, crossing the Old Bromsgrove Road, and up the turnpike at Five Ways, in the road to Hales Owen. Leaving this road also to the left, we proceed down the lane, towards Ladywood, cross the Icknield Street, a stone’s cast east of the observatory, to the north extremity of Rotton Park, which forms an acute angle, near the Bear at Smethwick.

From the River Rea to this point, is about three miles, rather west, and nearly in a straight line with Edgbaston on the left. We now bear north-east, about a mile, with Smethwick on the left till we meet Shirland Brook, in the Dudley Road; thence to Pigmill. We now leave Handsworth on the left, following the stream through Hockley Great Pool, cross the Wolverhampton Road, and the Icknield Street at the same time down to Aston furnace, with that parish on the left. At the bottom of Walmer Lane we leave the water, move over the fields, nearly in a line to the post by the Peacock, upon Gosty Green.

We now cross the Lichfield Road, down Duke Street, then the Coleshill Road at the A B House. From thence along the meadows to Cooper’s Mill; up the river to the foot of Deritend Bridge, and then turn sharp to the right, keeping the course of a drain in the form of a sickle, through John-a-Dean’s Hole into Digbeth, from whence we set out.

In marching along Duke Street, we leave about seventy houses to the left, and up the river Rea, about four hundred more in Deritend, reputed part of Birmingham, though not in the parish. This little journey, nearly of an oval form, is about seven miles.

The Francis White Directory of 1849 describes Birmingham as:

a Parish, Market Town, and Borough, situated near the centre of the kingdom, in the north western extremity of the County of Warwick, in a sort of peninsula. A small brook, at the distance of about 1½ mile from the centre of the town of Birmingham, separates this county from that of Stafford; and a narrow tongue from the county of Worcester runs into Warwickshire, on the east side of Birmingham. For Ecclesiastical purposes Birmingham is divided into the district parishes of St Martin, St George, St Thomas, and All Saints, in the Archdeaconry of Coventry and Diocese of Worcester.

There seems to be no trace of any prehistoric existence in Birmingham, the suggestion being that the marsh land in the Rea valley would not have attracted any such settlement. When the Romans arrived they set up camp at Metchley in Edgbaston, where the Queen Elizabeth hospital now stands, and built a station on a nearby hill. Named Bremenium, Bre and Maen meaning the high stone, it provided a good view of the surrounding country. Ryknield Street passed to the west of what we now know of as Birmingham, and joined the camp at Metchley with the camp at Wall, near Lichfield. It ran through Hockley into Handsworth and then on to Sutton Park.

Of Ryknield Street Charles Pye wrote:

The old Roman road, denominated Iknield-street, that extends from Southampton to Tynemouth, enters this parish near the observatory in Ladywood-lane, crosses the road to Dudley at the Sand Pits, and proceeding along Warstone-lane, leaves the parish in Hockley-brook; but is distinctly to be seen at the distance of five miles, both in Sutton Park and on the Coldfield, in perfect repair, as when the Romans left it.

The first evidence of the beginnings of a town, or-be-it a village, in these early centuries was in Saxon times. Here a small settlement was established in the scrubland and woods that formed part of the Forest of Arden, which then covered a large area of Warwickshire and parts of Staffordshire between the River Avon and the River Tame. Although no actual documentation exists, it is thought that an officer, who came over during an invasion in AD 582 was given the land as a reward and that it was his family who eventually took the name ‘de Bermingham’.

It was Peter de Bermingham who is first recorded as using the name when in 1156 the manor, as it had now become, was granted a market charter by Henry II. For centuries the market was held regularly on a Thursday but with expansion in later centuries additional markets were held on Mondays and Saturdays. In 1251, William de Bermingham acquired a charter from Henry III to hold two fairs in the town; one at Whitsun, commencing on the eve of Holy Thursday and continuing for four days, the other on the eve of St Michael, continuing for three days.

The manor house, home to the ‘de Bermingham’ family, was known as The Moat and stood close to St Martin’s Church just west of Digbeth, with the water supply for the actual moat coming from a small stream fed by the River Rea. This stream flowed from Vaughton’s Hole on the border with Edgbaston. Of the moat, William Hutton wrote ‘being filled with water, it has the same appearance now as perhaps a thousand years ago, but not altogether the same use. It then served to protect its master, but now to turn a thread mill.’

St Martin’s Church and the Bull Ring, early 1900s. Once the centre of medieval Birmingham. (Author’s Collection)

The manor house is known to have existed at the time of the Domesday Book but how far back it went before then is not known. However, in the 1960s excavations were carried out in order to build a new ring road and it was discovered that the entrance seemed to point away from what was the town centre in medieval times, suggesting the building was there before the town had developed around the market. Maps of the 1700s for the area show that all medieval buildings had gone and then in the early 1800s The Moat was also demolished to provide space for a new market.

By 1538 Birmingham had a population of 1,500. It was made up of one main street, a few side streets and 200 houses. However, the manor was now no longer owned by the de Bermingham family.

Edward Bermingham was born in 1497 and, because his father had died, succeeded his grandfather at the age of 3. A ward-ship was granted by Henry VII to Lord Edward Dudley but by the time the young Edward was old enough to take charge of the manor, the Dudley family had become ambitious. John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, wanted the manor for himself and offered to buy it but Edward refused. Determined to have it, Dudley hatched a dastardly plan. He arranged for some men to be on the road at the same time as Edward, then having met him to strike up a conversation with him and to continue to ride with him. Further up the road another man would be waiting for them. The plan fell into place and when Edward arrived at the designated spot his new companions drew their guns and robbed their waiting accomplice. Keeping up the pretence, the man reported the robbery and Edward, being highly recognisable, was arrested. The other men, of course, were never found so Edward, despite protesting his innocence was tried, found guilty and sentenced to death. His lands were confiscated by the King and Dudley was then able to acquire them for himself. However, he did arrange for Edward to be pardoned and he was given an income of £40 a year in compensation for the loss of property.

William Hutton tells us that the place the robbery took place was Sandy Lane in Aston.

Afterwards the Bermingham family seem to fall into obscurity, except William Hutton does say that he once met a man who had the name Birmingham and ‘was pleased with the hope of finding a member of that ancient and honourable house; but he proved so amazingly ignorant, he could not tell whether he was from the clouds, the seas, or the dunghill; instead of tracing the existance of his ancestors, even so high as his father, he was scarcely conscious of his own.’

However, in this modern age, a search on various family history sites bring up a lot of people in Birmingham with the name Birmingham in various genealogy records. Perhaps someone has done their family history and has found they are descended from this illustrious family. Or perhaps you will.

In the 1500s Birmingham was growing and had a successful industry in the weaving and dyeing of wool, and the making of leather goods. But also a new industry, which was to shape the future of Birmingham, was established. With the natural resources of iron ore, coal and streams, many forges and water mills were being set up where knives and nails could be made. The iron ore provided the necessary material for these items, the coal and the streams provided the fuel needed to power to the forges.

Between 1538 and 1543 John Leland, a poet and antiquary, travelled through England making observations, which he sent to Henry VIII. Of Birmingham he wrote, as reprinted in Francis White’s Directory of 1849,

I came through a pretty street as ever I entered, into Birmingham town. This street, as I remember, is called Dirtey (Deritend). In it dwell smiths and cutlers, and there is a brook that divides this street from Birmingham, an hamlet member belonging to the parish thereby. There is at the end of Dirtey a proper chapel, and mansion house of timber (the moat) hard on the ripe (bank) as the brook runneth down, and I went through the ford by the bridge, the water came down on the right hand, and a few miles below goeth into the Tame. This brook, above Dirtey, breaketh into two arms; that a little beneath the bridge close again. This brook riseth, as some say, four or five miles above Birmingham, towards black hills. The beauty of Birmingham, a good market town in the extreme parts of Warwickshire, is one street going up alonge, almost from the left ripe of the brook, up a mean hill, by the length of a quarter of a mile. I saw but one parish church in the town. A great part of is maintained by smithes, who have their iron and sea-coal out of Staffordshire.

The oldest building in Birmingham is undoubtedly the Old Crown Inn, having been standing on the High Street in Deritend since 1368, and it seems the same family owned it for many years as Showell’s Dictionary tells of a Mr Toulmin Smith, ‘in whose family the Old Crown House has descended from the time it was built’. The writer goes on to say that it was thought Deritend was originally known as Deer-Gate-End but that ‘Leland said he entered the town by Dirtey, so perhaps after all Deritend only means ‘the dirty end’. ‘We are also told that Digbeth was known as Dyke Path, or Dicks’ Bath, and was another puzzle to the antiquarians, ‘It was evidently a watery place, and the pathway lay low.’

It does not seem that Birmingham became too involved in the Civil War, although it is listed as being a parliamentary town. However, the Battle of Birmingham did take place on 3 April 1643 around Camp Hill when a company of Cromwell’s men from a garrison in Lichfield, together with some local men, tried to prevent a Royalist detachment led by Prince Rupert from entering the town. Prince Rupert’s battalion of foot soldiers and cavalry killed a number of inhabitants and burnt around eighty houses, causing damage amounting to £30,000. Then, at the end of that year, Parliamentary soldiers, again with the help of some townsmen, captured Aston Hall.

By the end of the 1600s the population of Birmingham amounted to 4,000 and an anonymous writer, whose comments were published in Showell’s Dictionary of Birmingham, wrote in 1691 that:

Bromichan drives a good trade in iron and steel wares, saddles and bridles. A large and well-built town, very populous, much resorted to, and particularly noted a few years ago for the counterfeit groats made here, and dispersed all over the kingdom.

In 1731 another anonymous writer spoke of the people of Birmingham being – ‘mostly smiths, and very ingenious in their way, and vend vast quantities of all sorts of iron wares’.

In 1766 A New Tour through England, written by George Beaumont and Capt Harry Disney, describes Birmingham as:

a very populous town, the upper part of which stands dry on the side of a hill, but the lower is watry, and inhabited by the meaner sort of people. They are employed here in the Iron Works, in which they are such ingenious artificers, that their performances in the smallwares of iron and steel are admired both at home and abroad.

The London Chronicle wrote in August 1788 of a gentleman who visited Birmingham and said. ‘The people are all diminutive in size, sickly in appearance, and spend their Sundays in low debauchery.’ Of the manufacturers he noted that there was ‘a great deal of trick and low cunning as well as profligacy’.

During the 1700s those small but ‘ingenious’ people in Birmingham had doubled in size. In 1720 the population had risen to almost 12,000. Thirty years later that figure had doubled. By the end of that century it had risen to 73,000, with a census in 1801 giving a population of 73,670. Industry was also booming. Metal workers were producing numerous items including shoe buckles, buttons, pens, knives and bolts. Brass was also popular, as was gun making.

It was during the 1700s that industry took an important role in the development of Birmingham and one man who played a major role in this was Matthew Boulton and his innovation, which was the Soho Works.

Soho was just a barren heath between Birmingham and Handsworth but in 1756 Edward Rushton leased a piece of land, deepened Hockley Brook and built a small mill. Eight years later Boulton purchased the lease from him and the site was transformed. A directory of 1774, an extract of which was published in Showell’s Dictionary, described the works as consisting of ‘four squares of buildings, with workshops, &c., for more than a thousand workmen’. Soho House, the home Boulton bought for himself in order to be on the doorstep of his works, was host to many celebrities of the day; inventors rubbing shoulders with lords and ladies, students with philosophers and such-like.

Soho House. The home of Matthew Boulton, now a museum celebrating his life and work. Bought in 1766 when just a farmhouse, Boulton spent many years renovating it into a gentleman’s mansion typical of the Georgian era. (Author’s Photograph)

Up until this time the roads around Birmingham had not been good. In 1659 it took four days to get from London to Birmingham, but this had improved by 1747 and coaches were advertising that the journey could be done in two days. With the lack of a navigable river and roads of poor quality, the development of Birmingham had been slow but the river did have its uses, as Charles Pye writes:

The only stream of water that flows to this town is a small rivulet, denominated the river Rea, which takes its rise upon Rubery Hill, near one mile north of Bromsgrove Lickey, about eight miles distant, from whence there being a considerable descent, numerous reservoirs have been made, which enables the stream, within that short space, to drive ten mills, exclusive of two within the town; and what is very remarkable, some person has erected a windmill very near its banks, where the ground is not in the least elevated. The curiosity of a windmill being erected in a valley, is very visible soon after you have passed the buildings on the road to Bromsgrove.

After leaving its source the River Rea travels through Rubery and Longbridge, and after travelling through an underground culvert, reaches Northfield. From there it runs through Stirchley, Cannon Hill Park, Balsall Heath to Digbeth. Stretching 14 miles, it joins the River Tame at Gravelly Hill.

It was the development of the canal system that helped in the expansion of Birmingham and its industry. An act in 1767 saw the building of a canal between Birmingham and the collieries near Wolverhampton and Wednesbury, meaning the easier distribution of coal, which had previously been transported by land. Following the opening of the canal, there was an immediate reduction in the price of coal. Eventually the canal was extended to reach the Staffordshire canal.

Charles Pye wrote of the canal system in 1812:

In the year 1767 an act of parliament was obtained to cut a canal from this town to the collieries, which was completed in 1769, at the expense of £70,000. There is now a regular communication by water between this town, London, Liverpool, Manchester and Bristol; to the three former places, goods are delivered on the fourth day, upon a certainty; there being relays of horses stationed every fifteen minutes.

The Dictionary of Birmingham tells us that on 6 November 1769 the first boat-load of coal arrived in Birmingham from Bilston and was ‘hailed as one of the greatest blessings that could be conferred on the town’.

In 1793 the cutting of the Warwick canal began and Pye wrote:

The Warwick Canal was opened for the passage of boats, by forming a junction with the Birmingham canal by means of which goods may be conveyed from the upper part of this town, to London, one whole day sooner than they can by steering immediately into the Warwick canal. At King’s-Norton, this canal is conveyed under ground, by means of a tunnel, two miles in length, which is in width 16 feet and in height 18 feet, yet it is so admirably constructed, that any person by looking in at one end, may perceive day-light at the other extremity.

There was a price to pay for the convenience as a small charge was made per tonnage. But most thought it was worth it in order to save a day’s travel. And going along the new route boatmen also avoided twelve locks that could cause wear and tear on their boats.

During the first week in January 1800 newspapers reported the opening of this new canal, plus another:

At 12 o’clock on Thursday, a boat, loaded upwards of 20 tons of coal, navigated along the Warwick and Birmingham canal, and a boat, loaded with 100 qrs. of lime, navigated along the Warwick and Napton canal, met at the junction of the two canals, at Warwick; their arrival was announced by the firing of cannon and ringing of bells, and received with the loudest acclamations by a great concourse of spectators, assembled on the occasion. A wagon, loaded with coals from the boat, was drawn through the town by men, attended by several of the canal proprietors, several inhabitants of the place, and more than 600 men who had been employed in the works, walked in procession, with a band of music, flag flying, &c. The opening of these canals will be a vast advantage to the trade of Birmingham with the metropolis. Goods sent by water, via Warwick and Oxford, will have 41 mile less to go than by any other navigation.

The canals were a great asset to Birmingham industry as Charles Pye continues:

the trade of this town has within the last fifteen years increased in an astonishing manner, for in the year 1803, six weekly boats were sufficient to convey all the merchandize to and from this town to Manchester and Liverpool but at the present time, there are at least twenty boats weekly employed in that trade.

Other canals joined the system around Birmingham, which provided a link not only with Dudley, Stourbridge, Fazeley, Coventry and Warwick but further afield to Oxford, Manchester and Liverpool. However, the building of the canal system was no easy task for the canal engineers. The steep inclines and slopes around Birmingham meant an abundance of locks. The canal to Wednesbury had to be built up a hill, which meant the construction of six locks. It took twenty-four years to build the Worcester to Birmingham canal.

So Birmingham, once cut off through having no navigable river in its vicinity, was now accessible to the rest of the country with an abundance of waterways and as described by Charles Pye: ‘Notwithstanding there is only one stream of water, the streets are so intersected by canals, that there is only one entrance into the town without coming over a bridge, and that is from Worcester.’

Birmingham may have avoided any involvement in the Civil War but in the space of just under fifty years it was to witness two vicious assaults on some of its residents and property.

In 1791, with the French revolution still in the minds of people, many were becoming suspicious of those who had become dissenters, in particular their head, Joseph Priestley. So when a notice appeared in the newspapers inviting ‘like-minded people’ to a dinner at the Dadley Hotel on Temple Row suspicions were raised. The dinner for eighty-one guests took place on Thursday, 14 July at 3 o’clock, and while the guests dined a mob gathered outside. It started quite peaceable with jeering and booing but then someone supposedly heard a toast being made of ‘destruction to the present government and the King’s head upon a charger’. What followed was a weekend of terror.

The mob rushed into the hotel, breaking windows and furniture and as the diners tried to make their exit they were pelted with stones. From there some of the mob went to Priestley’s meeting house and set fire to it, while others went to his house at Fair Hill and set fire to that – although not before looting his cellar and becoming intoxicated on his wines. As more joined the mob, other houses suffered the same fate: John Ryland’s house on Easy Hill; John Taylor’s property, Moseley Hall; William Hutton’s house on Bennetts Hill and many more all over the town, including other meeting houses. All the time the rioters were chanting, ‘Long live the King, Church and State. Down with dissenters.’ Soldiers came from both Oxford and Nottingham but it took all weekend to dispel the rioters. Many scattered and avoided arrest. Of those who were arrested, only two were hanged for their so-called crimes: Francis Field and John Green. Others miraculously found themselves alibis.

The Chartist Riots took place in the summer of 1839. There had been a large number of Chartist meetings all over the country and on 1 July they started assembling in the Bull Ring in Birmingham. The police tried to move them on but were attacked with the flag poles the crowd were carrying. Soldiers arrived to help and forced the crowd down Digbeth and eventually to St Thomas’ Church. Here the mob pulled out the iron palisades from around the church and used them as weapons. On this occasion they were eventually dispersed but two weeks later another meeting was organised that was to take place at Holloway Head and 2,000 people assembled. At first it was very peaceful but when it ended large groups went on the rampage. Rushing down to the Bull Ring and the streets of Deritend, they threw stones at windows and broke iron palisades to use as weapons. They ransacked shops and made bonfires of the contents they had dragged from the buildings. Furniture was destroyed and goods from the shelves were piled high on the bonfires, in fact anything that could be burned was thrown on to the fires. Eventually the military arrived to assist the police and the mob fled. Thirty people were arrested. Four were eventually executed, while others were sentenced to transportation for varying periods.

It would be another hundred years before Birmingham saw devastation such as this and by then it would have grown and developed at an alarming rate, once again all down to a new transport system.

In the 1800s the canals around Birmingham were becoming so populated they were at times too overcrowded and so thoughts quickly turned to the new mode of transport – the railway.

As early as 1824 a suggestion had been made in parliament regarding the building of a railway in Birmingham, but it had been refused. Six years later another survey was drawn up for a line to be built between Birmingham and London. Eventually the act was passed and the work began in June 1834. It took four years to complete and by September 1838 passengers could travel not only to London but locally to Coventry and Rugby, too.

At first there were two separate companies – the London & Birmingham Railway Company and the Grand Junction Railway Company. Both had their stations side-by-side in Curzon Street. Then in 1846 they merged to become the London and North Western Railway, taking passengers to Manchester and Liverpool, and locally to Walsall and Wolverhampton. When other lines were completed, passengers could travel to Bristol and the West Country or north to Derby, Sheffield, Newcastle upon Tyne and then on to Scotland.

There were other railway stations in Duddeston Row, Lawley Street, Vauxhall and Camp Hill, but it was soon realised that a central station was necessary and New Street was the chosen spot. Work to clear the area began in 1846 and Showell’s Dictionary of Birmingham tells us that ‘several streets were done away with, and the introduction of the station may be called the date-point of the many town improvements that have since been carried out. The station, and the tunnels leading thereto, took seven years in completion, the opening ceremony taking place June 1, 1853.’

There was no grand opening, just a low-key ceremony as passengers had actually been able to use the station since 1851.

The coming of the railways were not only good for the economy of Birmingham but also for its well-being. In 1900 Thomas Anderton wrote of the squalor of the previous thirty years and that these improvements had been slow, with the powers-that-be too careful and economical to make any changes. However, he also wrote that:

the construction of the London and North Western Railway station cleared away a large area of slums that were scarcely fit for those who lived in them. A region sacred to squalor and low drinking shops, a paradise of marine store dealers, a hotbed of filthy courts tenanted by a low and degraded class, was swept away to make room for the large station. The Great Western Railway station, too, in its making also disposed of some shabby, narrow streets and dirty, pestiferous houses inhabited by people who were not creditable to the locality or the community, and by so doing contributed to the improvement of the town.

Birmingham now saw an even larger opening for its commercial businesses with a quicker turnover in the movement of both the raw materials it needed for its factories and its ability to pass on the finished product to its customers. All this needed more workers and so the population increased as workers arrived from other parts of the neighbouring counties and even farther afield. This saw the need for more public buildings.

The Public Office and prison had been built on Moor Street in 1805 and contained the offices for the Street Commissioners as well as the magistrates’ court but by 1830 it needed to be enlarged. Thirty years later, in 1861, it was enlarged again.

The original prison in Peck Lane had opened in 1697 and was extended in 1757. In Showell’s Dictionary of Birmingham we read that:

A writer, in 1802, described it as a shocking place, the establishment consisted of one day room, two underground dungeons (in which sometimes half-a-dozen persons had to sleep), and six or seven night rooms some of them constructed out of the Gaoler’s stables. The prisoners were allowed 4d per day for bread and cheese, which they had to buy from the keeper. In 1806 a new gaol was built at the back of the Public Office in Moor Street which consisted of two day rooms, sixteen cells and a courtyard.

The new gaol was built to avoid the gathering of crowds who came out to watch the prisoners travelling between Peck Lane and the Public Office. It was only used as a temporary holding place while the prisoner was being held in custody. Once they had been charged by the magistrates, in most cases, they were sent to Warwick gaol to await their trial at the assizes. When the Victoria Law Courts were opened in 1891 the Moor Street site was eventually developed into a railway station and the lock-up was moved to Steelhouse Lane, where a tunnel under Coleridge Passage was used to move prisoners between the cells and the court.

For petty crimes, punishment could be a session in the stocks. The stocks were situated in the yard at the Public Office. Prior to 1806 they were at Welch Cross, at the junction of Bull Street, High Street and Dale End.

Previously the office for the Justices of the Peace was situated in Dale End and a prison on the High Street in Bordesley. In 1802 this prison was classed as the worst gaol in England as Showell’s tells us that:

the prison was in the backyard of the keeper’s house, and it comprised two dark, damp dungeons, twelve feet by seven feet, to which access was gained through a trapdoor, level with the yard and down ten steps. The only light or air that could reach these cells (which sometimes were an inch deep in water) was through a single iron-grated aperture about a foot square. For petty offenders, runaway apprentices, and disobedient servants, there were two other rooms, opening into the yard, each about twelve feet square.

The use of the underground rooms was discontinued in 1809.

The imposing and austere Victoria Law Courts c. 1900. (Author’s Collection)

The old Debtors’ Prison was in Philip Street in a small courtyard and consisted of one dirty damp room, 10ft by 11ft at the bottom of seven steps. Sometimes this room held fifteen people at one time, male and female. This was also closed in 1809 with the building of the new Public Office.

As Birmingham was part of Warwickshire, the majority of criminals were taken to Warwick Gaol and tried at the Warwick Assizes. It was not until the 1840s that Winson Green Prison was built.

Built between 1845 and 1849, Winson Green Prison contained 321 cells for both men and women. When it opened on 29 October 1849 it was known as the Gaol at Birmingham Heath. In 1885 it became a hanging prison for those convicted at the Birmingham Assizes. The first man hanged there was Henry Kimberley for the murder of Emma Palmer.

The foundation stone for the Victoria Law Courts was laid by Queen Victoria on 23 March 1887. She arrived at Small Heath station at about 1 o’clock, from where a small procession of soldiers, police and firemen accompanied the two carriages which carried her and her entourage to the Town Hall. The streets were crowded and she arrived at the Town Hall just after 2 o’clock to a fanfare of trumpets. After a short musical presentation, the Queen had a private lunch. Afterwards the procession took her to Corporation Street, where the first stone lay waiting. She tapped the stone three times with an ivory mallet and then left for Snow Hill station and her return to Windsor.