5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

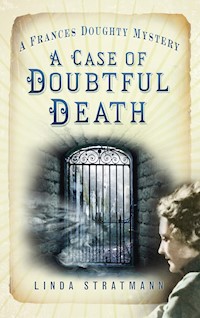

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

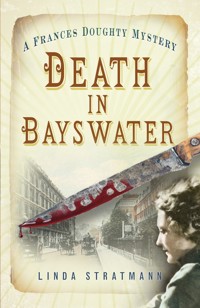

The year is 1880. In West London, a dedicated doctor has set up a waiting mortuary on the borders of Kensal Green Cemetery, where corpses are left to decompose before burial to reassure clients that no one can be buried alive. When he collapses and dies on the same night that one of his most reliable employees disappears, Frances Doughty, a young sleuth with a reputation for solving knotty cases, is engaged to find the missing man, but nothing is as it seems. In this, her third case, Frances Doughty must rely on her wit, courage and determination – as well as some loyal friends – to solve the case. Suspicions of blackmail, fraud and murder lead to a gruesome exhumation in the catacombs, with shocking results. The third book in the popular Frances Doughty Mystery series.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the Friends of Kensal Green and the General Cemetery Company with especial thanks to Lee Snashfold and Henry Vivian-Neal for all their help with my research.

www.kensalgreencemetery.com

www.kensalgreen.co.uk

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Author’s Note

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

In the cooler months, Henry Palmer’s most important duty was to keep the coal fires of the mortuary burning steadily. After all, as Dr Mackenzie used to say with his most engaging smile, an expression that ladies often commented was wasted on the dead, it wouldn’t do for the ‘patients’ to be too cold. Cold was the enemy of putrefaction, and worse than that, it paralysed the living, giving them a ghostly semblance of death that could delude the most skilled physician into certifying that life was extinct. While eminent medical men were confident that cures to the deadliest of disorders were almost within their grasp, science was still plagued with fundamental uncertainties. One of these, declared Dr Mackenzie, whatever practitioners liked to claim (and where, indeed, was the doctor of medicine who would ever admit to making a mistake?) was the infallible diagnosis of death. Failure to see the spark of life in a pale still form which seemed to have given up its last breath was, in his opinion, the worst possible error a doctor might make, for it could lead to horrors almost beyond human imagination.

The causes and consequences of premature burial were something he had made his special study for many years. To Mackenzie, the establishment, of which he was both founder and chief director, was not a place of death, but of reassurance. He called it the Life House, and the new admissions, who were laid gently on flower-strewn beds, were, at his express instructions, referred to as patients, and never corpses. He even ensured that the main repository was divided by a curtain into male and female wards. It would never do for a patient to awaken and find themselves in the company of persons of the opposite sex, a shock which might have a fatal termination in someone already in a fainting state. Every patient, on first being admitted, was carefully examined, and if no sign of life was apparent, a length of thin cord was tied to a big toe and a finger, and connected to a bell, which was hung from a hook on the wall. Should any of the patients revive, the smallest movement would announce to the orderly employed to keep constant watch over the wards that one of his charges was alive, and every means of resuscitation that modern medicine could provide was at hand to ensure the speedy and effective restoration of consciousness.

As far as Henry Palmer was aware, in the fifteen years of the Life House’s existence no patient had ever revived. Enshrouded by the warmth of the carefully tended winter fire, or in balmier seasons, the glow of the sun seeping through high windows, there was no answering flush on sinking cheeks, no sheen of sweat on pallid brows, only the spreading and darkening stains of decay. From time to time, the sound of a bell would be heard, but that was only due to undulations of the abdomen brought on by putrefactive gases causing a tremor, which rippled into the dead limbs. Before long it would be necessary to inform relatives that the patient had undeniably passed away, and the remains would be consigned to a coffin, placed in a side room referred to as the ‘chapel’, and later borne to a final resting place in All Souls Cemetery, Kensal Green.

Palmer had a great deal of respect for Dr Mackenzie, despite his employer’s eccentric beliefs, and while many a man might have recoiled from the uncongenial and unrewarding work, the young orderly took satisfaction from knowing that he brought comfort to bereaved families. During the long, quiet hours spent with the dead he saw that all was neat and well kept, changed the linen coverlets, maintained the banks of fresh flowers around the silent forms, cleaned the bedsteads, and sprinkled and swabbed the floor with a solution of carbolic acid. The pungent tarry smell of the liquid, the odour of wilting bouquets and the warm nostril-stinging tang of burning coal were between them almost enough to conceal what would otherwise have been the most powerful smell in the building – the sickly odour of the decomposition of human flesh. He made a round of the patients every hour, looking for clues that life remained, and, finding none, entered the details in a report, priding himself on his meticulous and neatly-kept records. Dr Mackenzie, who lived close by in Ladbroke Grove Road, called twice a day, and his partner, Dr Bonner, daily. The third director, Dr Warrinder, was also a regular visitor, although Palmer felt that his interest was merely to supply an occupation for his retirement, something that had been forced on him by failing eyesight. The three doctors would solemnly examine every patient as Palmer gave them his verbal account of the day’s transactions, then they would read and initial his record book, and compliment him on a duty well done. There were occasional visitors, strictly by appointment, who were always medical men. Mackenzie abhorred the idea of prurient persons hoping to glut their gross tastes on scenes unfit for all but the eyes of professional gentlemen, and most especially would not tolerate visits from members of the press, or females. Families wanting a last view of the departed were never shown into the wards, the body being decently laid out in the chapel.

On the day of the funeral Palmer would be there in his good dark suit of clothes, looking like an undertaker’s man and assisting the bearers. It was only on the patient’s final day above ground that he allowed himself to think of whom he or she had once been, and say his own farewell. His sister, Alice, and her friend Mabel Finch, to whose company he had recently become very partial, had both said, not without a laugh from Alice and a blush from Miss Finch, that he was almost ladylike in his feelings, not that that was in any way a bad thing. Dr Mackenzie was also at the funerals, with large sorrowful eyes, a man of science forever searching for the truth and always disappointed.

Although friends and relatives were known to cling desperately to the hope that their loved one might not after all be dead, the prospect of revival was not something the Life House made much of in its message to the public. The enterprise made only one very clear guarantee. No customer of Dr Mackenzie’s Life House would ever be buried alive.

‘How very curious!’ exclaimed young detective Frances Doughty, making a careful study of a letter she had received that morning. It was a single sheet, with pale handwriting very lightly impressed upon the paper as if the writer was elderly or ill, and there were little stops and starts, suggesting that the composition of the message had been interrupted in a number of places by sudden and uncontrollable floods of emotion.

Sarah, her trusted companion and assistant detective, a burly woman whose broad, plain face and stern expression concealed a world of loyalty and kindness, looked up from the drift of lacy knitting that seemed to flow effortlessly from her powerful fingers.

‘New customer?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ said Frances, ‘her name is Alice Palmer, and she will be calling this afternoon.’ A small photograph wrapped carefully in light tissue as if it was a jewel, had been enclosed in a fold of the paper, and she showed it to Sarah. The sitter was a slender young man in his Sunday-best suit, looking self-conscious and clutching a hat. ‘Miss Palmer’s brother, Henry. Have you ever seen him?’

Sarah peered at the picture and shook her head. ‘No, I can’t say as I have. Isn’t he the man Reverend Day told us about in his sermon yesterday?’

‘Yes, Mr Palmer disappeared six days ago, and his family is very anxious for his safety. But here is a detail that piques my curiosity. For the last two years he has been working as an orderly at the Life House in Kensal Green.’

‘I’ve heard of that place,’ said Sarah, scornfully, ‘and they’ve no business calling it a Life House when all they do is take in dead folk. Coffins in and coffins out. I’ve never heard of anyone coming back to life.’

‘Nor I,’ agreed Frances. ‘There are stories of course, but they may be made up. But there is no denying that many people feel a great anxiety in case they should be taken ill and appear to be dead, and then buried before their time. If they know that they will be taken to the Life House it will put their minds at rest.’ Frances laid down the letter and photograph and picked up a copy of the Chronicle. ‘This, however, is the really interesting part. Henry Palmer disappeared on the very same evening that his employer, Dr Mackenzie, died.’

Sarah nodded. ‘So he could have murdered Dr Mackenzie and then run away?’

‘There are many ways that the two events could be connected,’ said Frances cautiously, ‘or it could be that they are not connected at all. There is such a thing as coincidence, and I do allow for that when events are in themselves commonplace and unremarkable. But, where two rare and unexpected things happen on the same day and concern people who are acquainted, that circumstance deserves a very close examination. It does appear, however, that there was nothing suspicious about Dr Mackenzie’s death, although he was only forty-seven. It says here,’ she went on, perusing the Chronicle’s obituary, ‘that he had been very ill for some time, and it was well known that he had a weak heart. He had been advised to rest or even give up business altogether, but in common with many dedicated gentlemen he chose to ignore his doctor’s warnings. On the evening of the twenty-first of September, he was making his usual rounds of the Life House when he appeared to faint, but it was soon discovered that he was dead. His associate, Dr Bonner, said that he died from disease of the heart brought on by a septic abdomen, almost certainly made worse by overwork.’

‘Did Dr Mackenzie get put in his own Life House, then, and left to go all rotten?’ asked Sarah.

‘Apparently so,’ replied Frances. She put the newspaper aside and waited.

In the few months that had elapsed since the shocking case of murder that had elevated Frances’ reputation in the public mind, Frances and Sarah had become quite settled in their new home and also into an acknowledged position in Bayswater society as ladies who could deal with any difficulty. Frances was spoken of in hushed tones across fashionable tea tables as a clever young woman of almost masculine mind, while a story had recently flown about the district of how Sarah had exposed the activities of a thieving footman by dint of picking him up and shaking him until the teaspoons in his pockets rattled.

They occupied a first-floor apartment on Westbourne Park Road, rooms which would, in the days when the house had been the home of a gentleman with offices in the City, have been family sleeping accommodation. There was a large front room, which made a comfortable parlour where they dined and received visitors. A smaller room at the back of the house was where Frances slept and where she also kept her late father’s writing desk and all her papers and books. The compartment which connected the two must once have been a dressing room, and Frances had hesitated, because of its small size and Sarah’s imposing width, to suggest that she might like to make it her sleeping quarters, but Sarah, anticipating Frances’ concerns, had at once appropriated it to her sole use, firmly declaring it to be the cosiest bedroom she had ever known.

The furnishings throughout were plain and practical, since Frances liked to be surrounded by things that were useful and easily kept clean. Ostentatious decoration, she believed, was something that should be reserved for important public buildings. She had been in too many homes where the acquisition of pretty trinkets had disguised a discontented household. When her friends, Miss Gilbert and Miss John, leading lights of the Bayswater Women’s Suffrage Society, had first called upon her, they had gazed upon the simple austerity of the parlour with expressions approaching panic, although they would not have dreamed of offering any comment or suggestion. Soon afterwards Frances had been sent, almost as one sends a parcel of food to a starving family, two large cushions made of maroon velvet with heavy gold fringes, one embroidered with the figure of Britannia and the other with Boadicea. Frances made a special point of always placing these on display whenever the ladies called for tea.

As to the matter of family portraits, an essential in any parlour, Frances was in some difficulty as she had only one, a study of her late brother Frederick taken on the occasion of his twenty-first birthday, and that she had placed in a prominent position. She had no pictures of her father, and if there had been any of her mother or of her parents’ nuptials, those she felt sure had been destroyed long ago. Sarah had a photograph of her eight brothers, but it was felt best to place this in another room, so as not to alarm visitors.

During the day, Frances and Sarah saw clients and pursued their enquiries. In the evenings, they sat in easy chairs before the fire, enjoying a princely feast of cocoa and hot buttered toast, and while Sarah wielded her needles, Frances read aloud from the newspapers. This was not merely for the entertainment they had to offer; as Bayswater’s busiest detective she must make sure to know everything she could about recent events and notable people in that bustling part of Paddington. Sarah’s tastes were for the more sensational items of news, anything that might make her open her eyes wide or even declare ‘well I never!’ She often laughed heartily at the reports in the Bayswater Chronicle of the sometimes unseemly quarrels between the men of the Paddington vestry, and commented that if she was there she would bang their silly heads together and then perhaps they would attend to their business more and there would be fewer holes in the macadam on Bishop’s Road.

Frances’ first venture into her new profession had not been without some anxiety. For several weeks she had worried less about solving cases than keeping herself and Sarah fed and housed. Fortunately the success of her first case, which was not unconnected with the recent General Election, had been followed by a secret meeting with a parliamentary gentleman as a result of which she had since been in receipt of a modest salary, on the understanding that her services would always be available to the government. It would not make her a rich woman, but it provided a measure of financial security.

That summer she had been entrusted with a mission of great delicacy. An eminent gentleman had asked her to deliver a message to a lady, a message of such sensitivity that it could not be committed to paper. Tact and discretion were required. Frances had duly delivered the message, but finding that tact and discretion were insufficient to achieve the desired result she had added a few firm and well-directed words of her own, thereby avoiding a scandal. Her probity and discretion had been appreciated in the form of a very handsome honorarium, and Prime Minister Mr Gladstone, who was torn between a natural compulsion to save her from an unsuitable life and his awareness of her usefulness, had made her the gift of a prayer book in which he had been kind enough to inscribe his signature. That item, too, occupied a place in the parlour, although modesty forbade Frances to show the dedication to visitors unless specifically requested.

For the most part, however, Frances’ commissions had been of a more mundane nature – discovering the whereabouts of erring husbands, enquiring after the honesty of ardent suitors, or recovering letters written in the heat of a passion that had since cooled.

The only case in which she had failed was a quite trivial one, and yet it remained on her mind. Mrs Chiffley was the wife of a prosperous tea merchant, and some months ago her husband had presented her with the gift of a parrot. Unfortunately, while her husband was away on business, Mrs Chiffley had carelessly allowed the bird to escape. She did not wish to advertise in the newspapers for its return in case her husband came to know of her error, neither was there the option of buying a replacement as the bird had very distinctive markings which Mr Chiffley had commented upon. Mrs Chiffley, in desperation, had come to Frances, offering a substantial reward for the safe recovery of her pet, but Frances could do no more than make discreet enquiries and ask her trusted associates to keep their eyes well open. The bird could have flown back to India or even China for all she knew, although she did occasionally submit to the fear that she would discover Mrs Chiffley’s parrot in the windows of Mr Whiteley’s emporium, its sapphire feathers enhancing a fashionable hat.

Frances could not help wondering if there were other private detectives who experienced failure. It seemed unlikely that she was the only one. Unfortunately, she did not know any other detectives and even if she had it would have been impertinent to say the least to ask them about their unsolved cases. She suspected that other detectives did not take their failures to heart as she did, but cast them aside without a trace of guilt and forgot them in a moment.

Closer to her inner soul was her indecision as to whether she should try to find her mother. Frances had been brought up to believe that her mother had died when she was three years old, and had not long ago found that the abandonment was of a more earthly nature, and in the company of a man. Early in 1864, her mother had given birth to twins, a girl and a boy, of whom her husband William had suspected he was not the father, but the girl had died very young. It was possible that Frances’ mother was still alive, and also her brother – perhaps, it had been hinted, a full brother – who would now be sixteen. Frances felt sure that she was equal to the quest, but still she hesitated. She was afraid not of what she might find, but that her efforts would be met with a cruel rejection. She had lived above her father’s chemist’s shop on Westbourne Grove for many years after her mother’s departure, and even now that she had quit the Grove, everyone there knew her new address, so if her mother really wished to see her she could easily discover where she might be found. Supposing her father to have been the obstacle to a reunion, her mother could hardly be ignorant of William Doughty’s death, a tragedy which had exercised the gossips of Bayswater for some weeks, and whose aftermath was still unresolved. It was the strongest possible indication that her mother, for reasons of her own, did not wish to be discovered. All the same, every time Frances pushed the idea aside it returned, and she tormented herself with the thought that her mother might have come into the shop as a customer, and never revealed who she was, and she might have seen and spoken to her and never known it. The only other place that she and her mother held in common was Brompton cemetery where her father, older brother and sister were buried. Frances went regularly to tend the graves, but saw no signs of another visitor, and no one could tell her if another lady came there.

With the hour approaching for the arrival of Miss Palmer, Frances peered out of the window. Although it was only September the weather had been shockingly inclement, and the early days of what had promised to be a delicious autumn had suddenly declined into a misty gloom and whole days of smoke-laden fog. A cab paused outside and a gentleman alighted, helping a frail-looking lady descend. Her head was bent and she was muffling her face with a woollen shawl. Frances watched them as they approached her door and then waited for them to be shown upstairs.

Frances supposed that other detectives must have offices where they saw clients across a desk, but she, having none, used the parlour table, which was always furnished with a carafe of water and a glass, so that nervous clients could moisten their throats, also a discreetly folded napkin which was often pressed into service as a handkerchief. A notebook and a number of sharp pencils were essential for recording what was said, but just as valuable to Frances was Sarah’s no less sharp observation and opinions.

Alice Palmer was twenty-two but she seemed faded like a portrait badly painted and left in the sun. Anxiety lay upon her, a deadly unseen canker that consumed her energy. Frances suspected that the young woman had barely eaten since her brother’s disappearance. Miss Palmer’s gentleman companion, who was scarcely older, helped her to be seated and introduced himself as Walter Crowe, saying that he and Alice were engaged to be married. Frances did not normally provide nourishment for her clients, but in this case, sent for tea and sponge cake. Mr Crowe smiled sadly as if to say that nothing could tempt Alice to eat until her brother was found.

Frances knew that asking timorous clients to talk about themselves often helped ease them into a frame of mind where they could talk more freely about the things that troubled them. She invited both Alice and Walter to tell their stories, and learned that Walter was the son of a journeyman carpenter, and, seeking to better himself, was now a joiner with his own business. Alice’s mother had died when she was seven, and she and her three brothers, of whom Henry was the eldest, had been left orphans when their father died in a railway accident four years later. Henry, who had been just fifteen at the time, had been the mainstay of the family, ensuring that all the children were kept clean and decently clothed, received an education and, in due course, found respectable employment. Her brother Bertie was now eighteen and worked in a butcher’s shop on the Grove, living above the premises, and sixteen-year-old Jackie was apprenticed to Walter and lodged with him. Alice worked in a ladies’ costume shop on the Grove, and she and Henry shared lodgings in Golborne Road.

The tea and cake arrived, and Sarah stared at Alice with an expression of savage determination, which Frances knew very well, realising that the young woman would not be permitted to leave the house without having accepted some nourishment. Alice, moved almost to tears of terror at Sarah’s look, sipped milky tea and put a fragment of cake into her mouth.

The Life House, Frances was told, was situated in Church Lane not far from the eastern entrance of All Souls Cemetery, Kensal Green. Henry’s duties lasted from midday to midnight every weekday after which the other orderly, a Mr Hemsley, was there for the next twelve hours. Henry had never complained about the nature of his work, or his long hours, or made any suggestion that he might seek other employment. He invariably walked home, but was careful to creep in quietly so as not to wake Alice, who was always in her bed by 11 p.m. He was a sound, reliable man, a man you might set your watch by and know that once he had promised to do a thing it was as good as done. He was the very last man to run away and put his family to worry and distress.

Tuesday the 21st of September had started showery, but as the day wore on the streets had gradually become occluded by a cold, grey fog. Alice had gone to her work that morning as usual, leaving Henry’s breakfast and some food for his luncheon on the table, and returned to find that the breakfast had been eaten, the dishes cleared, and the luncheon taken. She had gone to bed at her usual time, but when she awoke the next morning she saw, to her surprise and concern, that Henry’s bed had not been slept in. She was obliged to go to her work, but as soon as she was able, she sent an urgent message to Walter to say that Henry had not come home. From that moment Walter’s efforts to find her missing brother had been both determined and tireless.

Walter’s first action was to go to see Alice’s brother Bertie at the butcher’s shop, who confirmed that he had not seen Henry that day. Walter then sent Jackie to Golborne Road to see if Henry had returned home, but the boy came back with the news that Henry was not there.

Walter next called on Alice at her place of employment, hoping that Henry might have gone to see her or at least sent a note, but she had still heard nothing from her brother and was now almost out of her wits with worry. Walter then took a cab up to the Life House and found that while he was not permitted to enter the wards, which were the preserve of staff and medical men, he could be admitted to the side chapel, which he found crowded with visitors; friends of the recently deceased Dr Mackenzie who had come to pay their respects. The doctor’s remains were in an open coffin, surrounded by floral tributes and sad faces. There was nothing unusual about the corpse, which looked very peaceful.

Walter was informed by a distressed and exhausted Dr Bonner that his colleague had collapsed and died the night before, indeed Mackenzie had been speaking to Henry Palmer when he had suddenly clutched his stomach and chest, groaned with pain, and fallen. Bonner and Palmer had spent an hour doing all they could to revive him, but had at last given up hope. Bonner, who was well acquainted with Mackenzie’s history of ill health, was in no doubt that the doctor had indeed breathed his last. Since Bonner understood that Mackenzie’s landlady, Mrs Georgeson, waited up for her tenants so she could lock the premises at night, he had instructed Palmer to call on her and inform her of what had occurred. It was by then almost eleven o’clock, so Bonner had told Palmer that after speaking to Mrs Georgeson, there was no need for him to return to the Life House that evening, and he should go home. Palmer had departed as instructed, and Bonner had not seen or heard from him since, but then he would not have expected to. He had remained at the Life House after Palmer left until the arrival of the other orderly, Mr Hemsley, an hour later, and had then gone home to try and get a little rest. Early the next morning, he had notified Mackenzie’s friends by telegram, inviting them to a viewing at the chapel at ten o’clock. As far as he was aware he was still expecting Palmer back at the Life House at midday for his next period of duty.

Walter had observed but not spoken to the other partner in the Life House, Dr Warrinder. That gentleman had been very upset and was fussing about the place, constantly asking Bonner if he was sure that his friend was really dead. He had even held a mirror to Mackenzie’s nose looking for the misting that would show the doctor still breathed, but without finding anything that might give him hope.

Walter had next gone to Dr Mackenzie’s lodgings and spoken to the landlady Mrs Georgeson, who had just returned from viewing the body. She confirmed that Henry Palmer had come to the house a little after eleven o’clock the previous night to inform her of Dr Mackenzie’s death. He had left after a few minutes’ conversation and had last been seen walking down Ladbroke Grove Road. At this point in Walter’s narrative, Frances fetched a directory with a folding map on which he pointed out Henry’s most probable route home, going south down Ladbroke Grove Road away from the Life House, and making a left turn either down Telford Road, Faraday Road or Bonchurch Road, all of which would have led to Portobello Road, then turning right down Portobello Road for a short distance and left into Golborne Road.

It was about a ten-minute walk from Dr Mackenzie’s lodgings to Henry’s home, allowing for the darkness and the fog. Walter had carefully followed each of Henry’s possible routes, but had seen no sign of him. He asked everyone he met on the way if a man had been there and suffered an accident or been taken ill, but had learnt nothing. That evening Walter and the Palmers held a family conference and agreed that if Henry was not back by the next morning they would inform the police.

Early the next day Walter went to Kilburn police station. The desk sergeant listened with grave attention, but took the view that Henry would have been upset by the death of Dr Mackenzie and had either taken a little more drink than was good for him, or his mind had become temporarily unhinged. Walter had found it impossible to convince him that both these suggestions were out of character. He then spoke to an Inspector called Gostelow, who impressed him as a very sensible man, and promised that he would circulate Henry’s description to his constables and ask them to look out for the missing orderly, but he comforted Walter with the comment that in such cases most people turned up later of their own accord, looking more embarrassed than anything else. Given that Henry had experienced a shock, he thought that such behaviour was not unexpected. Walter was unhappy that nothing more was to be done at that stage, but accepted that since Henry was an adult and had been missing for less than two days, the matter was unlikely to be treated as an emergency. Fearing that Henry had met with an accident and was lying unconscious in a hospital bed, Walter then sent messages to every hospital in Paddington giving Henry’s description and asking if an unidentified patient had been admitted. There was another family conference, and it was decided to put an advertisement in the Penny Illustrated Paper, which was duly arranged, although it was by then too late for an engraved portrait to go in the current week’s edition. Walter also asked Reverend Day at St Stephen’s to make an announcement during his Sunday sermon.

Walter and Jackie went out searching together, visiting any public houses where Henry might have called, not that he frequented such places, but it was possible that after the shock of witnessing Dr Mackenzie’s death he might have felt in need of a restorative. They entered every shop along the way, stopped at market stalls, spoke to street traders, beggars and idle loiterers, showing them Henry’s photograph, but returned home exhausted and none the wiser.

On the Friday morning Walter, without telling Alice the nature of his errand in case it distressed her, visited the mortuaries at the Kilburn and Paddington workhouses to ask if any unidentified bodies had been recently brought in, but the only one received which was still unnamed was at Kilburn and it was that of a young woman, probably an unfortunate, who had drowned herself in the Grand Junction Canal about two weeks previously.

At Kilburn police station, Walter learned that all constables had been alerted to look for Henry, but so far without result. Walter’s next thought had been to interview the cabmen who drove along Ladbroke Grove Road, but due to the inclement weather on the night that Palmer had disappeared none could recall having seen him. Walter, seeing Alice’s health decline with the pain of uncertainty, had then suggested employing a detective. Miss Doughty, he had heard, was clever and sympathetic, and did not demand fees beyond what a working man might afford. They had some money put aside for the wedding but agreed that they were willing to spend it on finding Henry.

That very morning Walter had been present at the funeral of Dr Mackenzie at All Souls, Kensal Green, and looked carefully about him during the brief but heartfelt ceremony. Henry was not there. Walter had been worried enough until that moment, but once he saw that Henry Palmer, a man of duty and sensitive emotions, had not attended Dr Mackenzie’s funeral, he felt suddenly convinced that the young man was dead.

Frances felt a little guilty about taking the couple’s wedding savings, but as she looked at Alice, who was making a great meal out of her little corner of cake, she thought that if Henry was not found soon, there might be no wedding, but a funeral. Walter gently took Alice’s thin white hand and stroked it as if it was a piece of bone china that might break. He looked appealingly at Frances. ‘Do you think you can help us?’

‘I will make some preliminary enquiries,’ said Frances, ‘and if I feel there is nothing I can do, there will be no charge.’

‘And you’re to eat something,’ growled Sarah, looming over Alice, ‘because you’re no good to your brother like that!’

Alice crammed a piece of cake into her mouth and burst into tears.

Once the clients had departed Frances gave careful thought to all the many possible reasons for Henry Palmer’s disappearance. The two most important factors, she believed, were the character of the man, and the death of Dr Mackenzie. Everything that she had been told about Palmer suggested that he was most unlikely either to have turned to drink or gone insane. Even the possibility that the mortuary might close down following Dr Mackenzie’s death, a matter that cannot in any case have been determined that same night, would not have been enough to provoke any unexpected behaviour. Palmer was a young man of proven ability who might easily have found another post on the recommendation of Doctors Bonner and Warrinder, and he had calmly and resolutely seen his family through far worse crises than this. It followed that he had been overtaken by some unforeseen catastrophe, which had occurred somewhere between Dr Mackenzie’s home on Ladbroke Grove Road and his own in Golborne Road. If he had been taken ill, or met with an accident, and was lying insensible in a hospital or had lost his memory, or had died and was in a mortuary, the efforts of his family would surely by now have alerted an attendant to his identity. It was, thought Frances, far more likely that during his ten-minute walk under the concealing cloak of foggy darkness he had become a victim of foul play, which explained why those in the vicinity had seen, or professed to have seen, nothing. His body might in the course of time make itself known by foul odours emanating from a cellar or a drain. If Dr Mackenzie’s death had had anything to do with Palmer’s fate, it might only be that it had resulted in the young orderly having had the misfortune to be in a place where he would not otherwise have been at that time.

Frances, however, could not help wondering if Dr Mackenzie’s death, even though due to natural causes, had been brought on by some external factor as yet unknown, something that might have resulted in Henry Palmer’s disappearance. The last people who had seen Palmer alive were Dr Bonner and Mrs Georgeson. She composed notes to them saying that she would be calling for an interview, and ordered a cab.

CHAPTER TWO

Logic dictated that Frances should attempt to recreate Henry Palmer’s last known journey, but the night was closing in and she did not feel bold enough to retrace his steps on foot in the dark and the fog, while a possible murderer roamed at large. That would have to wait until daylight, when she might at least, weather permitting, be able to look about her.

Before setting out on her first call, Frances asked Sarah to take a message to two friends of hers who were always happy, in return for a small consideration and sometimes gratis, to supply information about Bayswater trade, often of a nature that was not publicly known.

Charles Knight and Sebastian Taylor, usually known as ‘Chas’ and ‘Barstie’, were two enterprising and energetic individuals, men of business whose fortunes appeared to ebb and flow with the tides. Since the summer they had been enjoying a period of comparative calm and, for them, stability. Their nemesis, a loathsome young man carrying a sharp knife, who was known only as the ‘Filleter’ and often lurked about Paddington exuding a noxious air of menace, had not been seen for some weeks, and while they anxiously awaited the glad news that he was in a place where he could no longer trouble them, Chas and Barstie had decided to become citizens of Bayswater. They had accordingly taken accommodation in Westbourne Grove above the shop of Mr Beccles, an elderly watchmaker. Chas, bulging with optimism at this recent development, spoke airily of their ‘apartments’ and their ‘offices’, his words conjuring up a picture of vast suites of elegance and comfort, as if the apartment and the office was not in fact one and the same location and numbered more than a single small room, and was not at the top of two flights of damp, narrow stairs. The elevation of the premises above street level was, thought Frances wryly, what justified Chas in claiming that he was going up in the world of commerce. They had recently established a company, The Bayswater Display and Advertising Co. Ltd, although whether that was actually the nature of its business Frances was unsure. Whatever it was they did, it seemed to involve long hours facing each other across a shared desk, a great deal of running up and down stairs, and occasional food fights.

‘Mr Palmer’s disappearance may have nothing at all to do with his occupation or any person at the Life House, but I must first satisfy myself of that before I dismiss the idea,’ Frances told Sarah. ‘If the gentlemen can tell me anything about the business, the directors or the employees, whatever it might be, that would be of the greatest assistance.’

Dr Mackenzie’s lodgings were on the east side of Ladbroke Grove Road, just a little to the north of its junction with Telford Road. The houses in that location were not so tall or so grand as those in other parts of the long thoroughfare, and the builder had not thought it necessary to encrust them with pillars and porticoes, but they were respectable enough. As Frances stepped up to the door she saw the top of a housemaid’s cap bobbing about in the basement area below. At the sound of the knocker, the maid turned her head up to look, her face a white circle, as pale as the cap, with watery grey eyes and a pinched nose. She said nothing, but made to go indoors at a pace that suggested that Frances might have to wait several minutes for admission. Moments later, however, the front door was opened by the landlady.

Mrs Georgeson was a capable-looking woman in her middle years. The hardened fingers that peeped from her mittens suggested a life spent in toil, but they were not roughened by recent work. Frances explained her errand while Mrs Georgeson studied her calling card as if it was a difficult acrostic. ‘So he’s not been found, then. You’d better come in.’

Frances stepped into the hallway finding it drab, and only tolerably clean; she felt sure that Sarah would have regarded the state of the cornices with something approaching indignation. Little flaps of wallpaper that might once have been flesh pink but had died away to the colour of weak coffee, curled like dried leaves edged with brown. A single gas lamp turned to its lowest setting supplied just enough light to pass through the hall, but failed to conceal an enforced neglect which the landlady might have hoped her potential tenants would not notice. Queen Victoria stared from the only portrait on the wall with an expression of stern disapproval.

‘There are only gentlemen lodgers here,’ said Mrs Georgeson, as she led Frances down the stairs at the rear of the house. ‘That was the position when Mr Georgeson and I chose to supervise the premises and so it has remained. Respectable single gentlemen, preferably those in the professions, they are so much more reliable.’ Mrs Georgeson, while having no ambitions to appear genteel, was determined to be accounted worthy, and revealed that her husband was engaged in work of the utmost importance to society. She was so evasive when Frances politely enquired as to the nature of Mr Georgeson’s occupation that she could only conclude it had something to do with sewage.

Near the foot of the stairs they met the housemaid on her way up, a tall thin girl, with long untidy curls of light hair wriggling from an over-large cap. She looked like a plant that had grown in too little light and was searching for the sun. She observed them gloomily, turned without a word, and went down again. At the bottom of the stairs there was a small, dark parlour, and the maid passed through it and disappeared into the next room, where a loud metallic clatter announced that this was a kitchen where she was busy either scrubbing pans or knocking them together to give the impression that she was. There was a faint odour of overcooked egg.

Frances and the landlady sat at a small table, where a large brown teapot that looked as if it needed a good scouring stood next to some used cups. Mrs Georgeson frowned at them as if she felt something needed to be done about this situation, and glanced at the kitchen door.

‘Please don’t trouble yourself,’ said Frances, quickly. ‘I would like you to tell me all you know of Dr Mackenzie. How long did he live here? Did your other tenants know him well?’

Frances learned that Dr Mackenzie had occupied the uppermost apartment in the building for the last three years, and had been a quiet and largely solitary individual. A Mr Trainor, who travelled in medical sundries, had lived on the ground floor for ten years and was, if anything, even quieter than Mackenzie. Mrs Georgeson did not think either man had visited the other’s apartments. The first floor had been empty at the time of Dr Mackenzie’s death following the departure abroad of the previous tenant, although a new gentleman had since moved in. Mr and Mrs Georgeson occupied comfortable rooms in the extensive basement and Mary Ann, who was sixteen and had worked there for a year, slept on a folding bed in the pantry.

‘Please describe the evening when Mr Palmer called to report Dr Mackenzie’s death,’ asked Frances. ‘This is extremely important, since as far as I have been able to gather you were the last person to see him before he disappeared.’

Mrs Georgeson made a little grimace as if the fact alone brought her closer to tragedy. ‘Of course I’ll tell you all I can but it’s little enough. And I have already said everything to Mr Crowe. Poor Dr Mackenzie had been so unwell, worn down and tired, and I said to him perhaps he ought not to go out as the weather was cold and foggy, and it might get on his chest and then you never know what might happen. But he insisted he had to go, and so I promised to wait up and see that he got a hot drink and perhaps a little sip of brandy when he came in. I was just starting to worry that he was late back when Mary Ann went to answer the door, and the next thing I knew she rushed down here in tears saying there was a man called to say Dr Mackenzie was dead. Of course I went up at once and found Mr Palmer in the hallway talking to Mr Trainor, who had come out of his room when he heard the commotion. I was told that Dr Mackenzie had suffered a fit and was now a customer of his own establishment.’

‘Had you met Mr Palmer before that day?’

‘No, never. None of us had.’

Frances was disappointed. Only someone who knew Palmer well could judge whether his mood and behaviour that night were characteristic of him. ‘Can you describe how he appeared to you?’

‘Well, he was upset of course, as you might expect, but not crying or anything like that. Shocked, I would say, but quiet and dealing with it like a man. He had a message to bring, a duty to do and he did it.’ She nodded, approvingly. ‘He told me there was to be a private viewing for the doctor’s friends and relatives next morning at ten, and I would be very welcome to attend, so of course I went up to pay my respects. Dr Mackenzie was a good man, always thinking of others, never of himself. He was in a little room at the side, laid out very nice with flowers and candles. Poor gentleman,’ said the landlady wistfully, ‘he had looked so ill these last few months; I’ll swear he appeared better once he was dead. Some of them do, you know, more at peace, all their troubles gone.’

‘Did Mr Palmer look like someone who might go away and have too much to drink to steady his nerves, or a man whose mind might break down with grief?’ asked Frances.

Mrs Georgeson considered this for a moment, and then shook her head. ‘I would say not. He just sighed and said he would go off home to his bed, but he didn’t think he would be able to sleep after what had happened. He said Dr Mackenzie had collapsed right into his arms and he would never forget it.’

‘Did you see Mr Palmer out?’

‘I did.’

‘And did you see where he went – what direction he walked in?’

‘Oh I couldn’t say – it was that bad out I just saw him to the bottom of the steps and then shut the door. Mary Ann might know, as she was back and forth.’

‘In that case, I had better speak to her.’

Mrs Georgeson called the servant from the kitchen, and Mary Ann emerged, peering about her as if short-sighted.

‘This is Miss Doughty, the detective,’ said Mrs Georgeson.

The transformation was immediate. The girl suddenly straightened from her miserable slouch, her mouth forming a dark circle of surprise. ‘Oh, are you the lady in the stories?’ she exclaimed.

‘Stories?’ said Frances. ‘You mean in the newspapers?’

‘No, I mean the halfpenny books. The Lady Detective of Bayswater. They’ve got pictures and everything.’

Frances gulped, having no idea that anyone had seen fit to illustrate her adventures and sell copies to impressionable young people. Her immediate instinct was to deny any connection, but then she realised that it was a situation she might turn to her advantage. ‘I have not seen the stories you mention, but they may very well be about me,’ she said.

Mary Ann beamed with excitement. ‘Oh you are very brave, Miss!’ she said, admiringly.

‘Thank you,’ said Frances, a little worried at what it was she was supposed to have done. ‘Now, I would like you to sit down and tell me everything you can remember about Mr Palmer who called here to say that Dr Mackenzie had died.’

Mary Ann sat at the table, and stared at Frances as if she was a lady of very great moment.

‘He was a nice-looking young man,’ she said, ‘very tidy and clean, with good manners; and sad. He said that Dr Mackenzie had fallen down all of a sudden, and he and the other doctor had done what they could to help him, but they were sure he was gone. I went to fetch Mrs Georgeson and then came back up the stairs because – to see if I was wanted for anything.’

Mary Ann’s milky face went a little pink and Frances realised she had crept up to the hallway to get another look at Henry Palmer. ‘But Mrs Georgeson said I should go back down to the kitchen, so I did. Has he still not been found, Miss?’

‘No, I am afraid not. Did you see where Mr Palmer went after he left here?’

‘Yes, I was in the area, and he came down the steps. He stopped for a while, like he was thinking about something, and then he turned and walked down the road.’

‘Did he turn the corner and go down Telford Road?’

‘No, I think he crossed over and went on walking. But it was very foggy and I didn’t see him after that.’

Frances nodded. ‘Thank you Mary Ann, you have been very helpful. I had better speak to Mr Trainor, now.’

‘He’s away on business,’ said Mrs Georgeson. ‘I expect him back on Thursday afternoon. I’ll let him know you called. I’m sure he would be more than willing to tell you all he knows.’

‘Then I will return to see him on Thursday. And now I would like to examine Dr Mackenzie’s room. Has it been re-let?’

‘Not as yet,’ said Mrs Georgeson with an air of disappointment, ‘but the room has been emptied, so there’s nothing for you to see.’

‘All the same,’ said Frances, ‘I will see it. Who disposed of the doctor’s effects?’

‘Dr Bonner. He and Dr Warrinder are the executors, but I think it’s Dr Bonner who does all the work. Not that there was a great deal for him to take. Medical books, mainly. Business papers. He asked me to give the clothes to charity. Come with me.’

They ascended two flights of thinly carpeted stairs where Dr Mackenzie’s apartments consisted of two small, comfortless rooms, a parlour and bedroom both with the simplest and plainest of furnishings. There was a sour, dusty smell as if the floor had been roughly swept but not assiduously cleaned.

‘If you know of any single gentlemen looking for respectable lodgings …’ said Mrs Georgeson, hopefully. ‘They get a boiled egg and tea every morning.’

‘I will be sure to mention that you have rooms available,’ Frances promised. She had always assumed that medical men lived in some affluence, but it was clear that Dr Mackenzie had subsisted on a very small income. ‘Did he have many visitors?’ she asked.

‘Some yes, his medical friends. No ladies – never any question of it. Dr Bonner called and Dr Warrinder, and young Dr Darscot.’

‘Dr Darscot? I don’t know that gentleman. Does he work at the Life House?’

‘Oh, that I couldn’t say. But he must have been a very great friend of Dr Mackenzie. He was very upset that night.’

Frances turned to her. ‘That night?’ she exclaimed. ‘Do you mean the night Dr Mackenzie died? Dr Darscot was here?’

‘Yes,’ said Mrs Georgeson, unaware that she had said anything of interest. ‘He came knocking at the door saying he wanted to speak to the doctor and it was very important and he wouldn’t take “no” for an answer. I had to tell him; I said Dr Mackenzie has just died.’

‘So Dr Darscot called quite late – after Mr Palmer had gone.’

‘No more than five minutes after, I would say. When I told him the doctor was dead he went into quite a state, wouldn’t hear of it, wouldn’t believe it, said it couldn’t be true, and demanded to go up to the rooms and see for himself. I told him, the body isn’t there, it’s at the Life House. Then he says he still wants to see in the rooms as the doctor had borrowed something from him and he wanted it back. I said I couldn’t let him up there – that the only person I would let up there was Dr Mackenzie’s executor, and once he had the papers to prove it was him he could do as he pleased. Then Mr Georgeson comes along and wants to know what the matter is and I told him. And he said the rooms were locked and would stay locked. And Dr Darscot looked very unhappy and ran out, calling for a cab.’

‘Did he return?’ asked Frances.

‘No, I’ve not seen him since.’

‘Do you have his address? I should like to speak to him.’

‘No, but I expect Dr Bonner will know.’

‘Very well, I shall be seeing him soon. And those were the only callers?’

‘As far as I know, yes. Those nights when Dr Mackenzie wasn’t at the Life House he was usually here working. He used to write medical papers and sometimes he gave talks to other doctors. And I think he had started to see patients again. Live ones, that is, only he didn’t see them here. I don’t know where he saw them. It was all work with him,’ she said sighing. ‘All work.’

‘Did he get many letters?’

‘Yes, from time to time.’

‘Who wrote to him?’ Mrs Georgeson bridled at the question and Frances paused, realising that in her eagerness to know the answer she had phrased the enquiry somewhat insultingly. ‘Forgive me; of course you could not possibly have known that unless he told you. What I meant to say was did he ever tell you who wrote to him?’

Mrs Georgeson accepted the apology with a nod. ‘He didn’t say, but there were letters posted in London, and from Scotland, and from somewhere abroad.’

Frances had seen all that she wished, but asked Mrs Georgeson to write and advise her when Mr Trainor was available. She returned home to find visitors in the parlour; Chas toasting currant buns before the fire and passing them to Barstie, who was covering them liberally with strawberry jam spooned from a jar.

‘Only the best, Miss Doughty,’ said Chas with a smile and a wink, as Sarah brought tea and plates. He was looking comfortable and prosperous, and Frances hoped fervently that he was not about to make a declaration of affection. He had once hinted that her expertise in maintaining the account books of her father’s business had excited his esteem, something he would not be able to acknowledge openly until he felt financially settled. While she wished him every success, she would be perfectly happy if he found another lady with which to share it. ‘Now then, you wanted to know all about the late Dr Mackenzie and his associates. I’m sorry to say there isn’t really a lot to tell.’

‘A very peculiar place, the Life House,’ said Barstie, thoughtfully. ‘I shouldn’t care for it myself.’ Barstie, a slender individual lounging casually opposite his plumper friend, had, Frances knew, spent the last two years in the amorous pursuit of an heiress who had so far remained immune to his attentions, a situation which gave him a permanently mournful air.

‘It’s one business I can think of where the customers don’t complain,’ said Chas. ‘If they’re dead why they can’t, and if they sit up again and take notice, well that’s all to the good. And families will pay any amount for peace of mind and a decent disposal of the remains. Death is the one certainty in life. There’s good money in death.’

Barstie sighed as if he could already see Chas making plans to open a new business.

‘Dr Mackenzie was not a prosperous man,’ said Frances. ‘I have seen his lodgings and they were very modest.’

‘He was a man of high principles,’ said Chas, ‘at least he always represented himself as one, and such men never prosper. He first promoted the idea of a Life House in 1862, although it was three years before he could open it. It was partly paid for with his own money, part came from Dr Bonner and the rest was collected by public subscription. He was paid the smallest salary he felt the business could afford, but it has not made a good profit yet, although it may well do in future. Funerals, on the other hand – you could name your price. We could start small, Barstie – lap dogs and kittens, pet monkeys and such like.’ Barstie’s despondency increased, but Chas breezed on.

‘Dr Bonner, now he is financially comfortable, but it’s not because of the Life House. Did well out of his medical practice, did even better by marrying a widow with property but no standing in society. Better still, she ignores him and spends all her time on ladies’ committees. He amuses himself nowadays by seeing rich patients with troublesome ailments who pay for his discretion, and elderly persons with something in the funds who he can persuade to become customers of the Life House.’ Sarah poured tea and handed him a cup, and he smiled and helped himself to a bun. ‘You are very kind, Miss Smith.’ Sarah did not look especially kind, but then she so rarely did.

‘Dr Warrinder,’ said Barstie, ‘is not a man of wealth, but neither is he poor. He used to be a consultant at the Hospital for Diseases of the Throat and Chest in Golden Square. Then there was that unfortunate occurrence three years ago, when a lady died after an operation. Words were said and Dr Warrinder thought it best to retire – from tending to the living at any rate. He lives quietly and modestly now.’

‘And Dr Darscot?’ asked Frances. ‘Does he work at the Life House?’

The two men glanced at each other with surprised expressions and shook their heads. ‘No, the only men employed at the Life House are the three directors and the two orderlies. No one called Darscot.’