Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

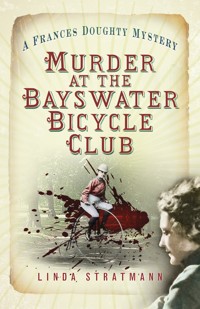

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Frances Doughty Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

London 1882: In this, her most demanding case, Frances Doughty goes undercover for Her Majesty's Government to investigate some disturbing information regarding the apparently innocuous Bayswater Bicycle Club. Before long, she is plunged into a murky world of deadly secrets, a suspicious disappearance and a brutal murder, and the Lady Detective is forced to do the unthinkable to avoid becoming the next victim. With a new and exciting future before her, is there anything the dauntless Miss Doughty cannot do?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to my husband Gary, who learned to ride a penny-farthing just for me, and Edwin J. Knight, who taught him how.

First published 2018

The Mystery Press, an imprint of The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uks

© Linda Stratmann, 2018

The right of Linda Stratmann to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8736 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

PREFACE

Summer 1881

Morton Vance was riding for his life, and he knew it. The worst of his predicament was that he couldn’t be sure exactly who wanted to kill him, or even how many of them there might be. He had found himself in the miserable and terrifying position of being able to trust no one, even, and in fact most especially, his fellow members of the Bayswater Bicycle Club.

What had started out as a pleasant and healthful exercise on a tranquil afternoon had led him into a nightmare. He had stumbled across the unthinkable, the unimaginable. It had taken time for his mind to accept what he had seen, to recognise that it was a horrible truth, and not a cruel prank or a delusion. Now he could not erase the sight from his mind. All he knew was that he had to get away as fast as possible.

More than ever he was thankful for the smooth and efficient performance of his new mount, the Excelsior, with its hollow front forks, sprung saddle, robust rubber tyres and 50-inch front wheel, so much better than the old boneshaker on which he had first learned to ride. As his feet pounded at the pedals, wheels throwing up little puffs of dust like smoke almost as if they were on fire, he wondered with grim irony if he was breaking a record, or achieving a personal best at least. He was certainly breaking the law, but that couldn’t be helped. For once he actually hoped he might meet a constable on the road who would want to pull him up for furious driving. A stiff fine was the least of his worries.

He was riding south down Old Oak Common Lane, and would normally have turned right into East Acton, but that was now the one place he had to avoid at all costs. He rode on, with broad open fields on either side, his path flanked by ditches and hedgerows, and the long culvert covering the flow of the old Stamford Brook, passing the occasional low stone cottage and sensing from time to time the hot reek of a pigsty. The worst threats here were the dry rutted road that could without warning cause a spill over the handlebars, and a possible encounter with Sam Linnett the pig keeper, who hated all bicyclists and never lost the opportunity of taking his horsewhip to a passing wheelman. Vance fixed his determination on one task; all he had to do was reach the Uxbridge Road and the well-populated route into Hammersmith and he would be safe.

In the warm quiet of the summer’s day, with barely a breeze to cool him, he began to hear what he had most dreaded, a whisper of sound behind, a narrow gauger on packed earth, the faint crunch of dry mud under rubber and metallic singing of turning cranks. He risked a rapid glance over his shoulder, and as he feared it was another bicycle, still too far away for him to recognise the rider, only that he was in the Bayswater club uniform; but whoever he was, he was pedalling fast and gaining.

Vance redoubled his efforts, but he was tiring, and the other man was better, fresher, long legs pumping strongly. He knew that he must be nearing a sharp curve in the road up ahead, and looked for the white marker post that acted as a warning sign, telling bicyclists that it was time to check their speed, but either he had failed to see it in his panic, or it was missing, and now, to add to his woes, he was unsure of exactly where he was and what he should do. It was a risk, but he kept going.

Moments later he saw the overhanging branches that signalled the curve in the road only yards away, and was obliged to put some back pressure on the pedals, to slow as much as he dared so as to avoid a spill. At least he knew his pursuer would have to do the same.

When he saw the new danger ahead it was far too late to avoid it. He tried to slow further, as safely as he could, knowing that too sudden a stop would only propel him forwards, parting him from the machine. He would then be offered the choice of all men who came a cropper from such a height, a broken skull or a flattened nose. The handlebars rocked in his grip as the heavy front wheel juddered and twisted, but his palms were sweating and he had still not come to a halt before he lost control. He made a last desperate swerving skid before the inevitable collision. It was side on, but more than enough to violently dislodge him, and he crashed out of the saddle and onto the rocky path, his stockinged shins cracking against the handlebars, his shoulder driving into the baked mud and collapsing with the unmistakable sound of fracturing bones, a thump on the side of his head following for good measure.

At last he came to rest, the dented frame of his prized Excelsior lying across him, its steel backbone warm like a living thing. Dazed and nauseous, his chest heaving for breath, he gazed up at the bright sun, knowing that this was his last pain-free moment before his shocked body began to register its injuries.

The other rider, perhaps more skilled, and having more time to react, must have avoided a crash, for he heard no sound of violent contact. Instead, there was a brief grinding of rubber on earth, signalling a sudden stop. A few moments later Vance heard footsteps coming towards him. Sweat dripped into his eyes, but despite the heat he began to shiver. A figure stood over him, a black silhouette against the clear bright sky. All hope of help vanished. He thought of his parents; he thought of Miss Jepson and the things he had meant to say to her and never had, and now never would. The figure did not speak. He was holding something, a staff or a cudgel, and raised it up purposefully over the fallen man. Vance closed his eyes.

CHAPTER ONE

Summer 1882

‘Good afternoon, Miss Doughty.’

On a clear and sunny afternoon, Miss Frances Doughty, often hailed in the popular press as London’s premier lady detective, was taking the air in Hyde Park, when as if by chance, she met a middle-aged gentleman of respectable demeanour.

As every government agent knows, if secrecy is essential there is no better place to hide oneself than in a teeming and diverse crowd of persons all earnestly devoted to their own individual business. The great undulating space of parkland, dotted here and there with clumps of craggy trees, was crossed by many paths along which groups of strolling visitors were strung like beads on silk, inhaling the grassy perfume, admiring clusters of flowering shrubs and whispering words of scandal, intrigue or romance. The more drably clad males of the species were accompanied and outshone by their ladies, who greeted the sun in brightly coloured dresses and straw bonnets garnished with ribbons. If the park was a little scant of shady woodland in which to linger, this was more than compensated for by small forests of parasols. There were solitary figures, too, artists with their sketchbooks and pencils trying to capture the refinements of nature, and idle youths lying on the cool thick grass and contemplating nothing at all.

At that hour of the day all the public gates were open, and far more persons were eager to enter the park than were prepared to depart. It was time for the fashionables to make themselves known, and promenade around the carriage drive in the kind of elegant equipages that most Londoners could only inhabit in their dreams. So profuse were they that vehicles slowed with every new arrival and occasionally even stopped altogether, giving the strolling crowds the chance to pause and speculate on which noble personages might be within. There were other carriages, too, a little brighter and smarter, the horses coiffed to perfection, which, it was believed, were occupied not by the higher ranked ladies of society but by the female gentility of quite another world, who attracted many curious eyes. Their smiles, at least, were offered gratis.

The early morning bathers had long departed the grey waters of the Serpentine, and their places had been taken by boats, both of the narrow variety propelled by diligent oarsmen and the miniature wooden sailing vessels of children, adding laughter and ripples to the atmosphere. Later that evening, as the sun declined and the hour of dinner approached, the park would be quiet, almost deserted, the carriages gone, the horses gone, the hire boats drawn up onto the banks of the Serpentine like beached dolphins, and new inhabitants would arrive, those for whom the turf was the only soft place where they might lay their heads, and others whose only thoughts were of mischief.

That afternoon, however, a lady and a gentleman who had important business to discuss without anyone taking particular notice, might well use Hyde Park for a secret meeting.

Frances took the gentleman’s arm, and after strolling for a few moments they found a bench and sat side by side, looking for all the world like a modestly clad niece enjoying the pretty scene with her favourite uncle. In all their meetings, Frances had never learned his name, or even asked for it, but he was a pleasant looking silver-haired man approaching sixty, who inspired both confidence and respect.

‘I trust you are well?’ he asked. There was a note of caution in his voice, and the creases around his eyes deepened with concern. It was more than just the usual polite enquiry.

Frances’ reply was strong and confident, yet calm. She knew that she often sounded and looked more confident than she felt, but her profession required it, and the deception had become easier with time. ‘I am, thank you, very well indeed.’

‘Last year we had some fears for your health.’

‘As did I, and my friends, but I am fully restored now,’ she assured him. ‘There were some terrible times, tragedies, actions on my part that I regret, and always will, and I still mourn those who are lost, but life continues, as it must. I continue.’

His expression eased and he nodded approvingly. ‘I am glad to hear it, because we have a new mission for you, and I wanted to be sure you could undertake it. It is,’ and he permitted himself a pause, ‘a little different from what you have been asked to do before. You may refuse it if you wish.’

‘Tell me,’ said Frances. ‘I am ready.’

A cluster of young women walked past, deep in conversation, stabbing the air with little trills of laughter. The gentleman was silent until they were out of earshot. ‘In two weeks’ time, the Bayswater Bicycle Club will be holding its annual summer meeting. There will be a large gathering of spectators, races, displays, sales of goods, a band, prize-giving, light luncheon and afternoon tea. You will attend.’

‘That sounds very pleasant. Where will the event be held?’

‘At Goldsmith’s Cricket Ground, East Acton. The club’s chief patron is Sir Hugo Daffin, a long-time enthusiast of the wheel who lives in Springfield Lodge nearby. The club members use rooms in his house for meetings and social events, and those who are unable to keep their bicycles at home in town can store them in his coach house together with the machines that are owned by the club and kept for hire to the public.’

‘And what must I do?’

He gave her a searching look softened by a slight smile. ‘As little as possible. Observe. Listen. Take great care not to draw attention to yourself. If you notice anything that strikes you as unusual, or suspicious, make a note of it. Remember, but write nothing down. As ever on these occasions, if your true intentions are suspected we will not admit to having sent you. And at the first hint of danger, you must leave at once.’

Frances absorbed this, but had to admit that there was little enough to absorb. ‘Can you tell me nothing more? For what am I looking or listening?’

The gentleman considered this question for a while, and she guessed that he was debating with himself how much he might safely tell her. At length he spoke again. ‘We believe that the club is being used by unscrupulous and traitorous persons to carry secret messages and stolen documents to anti-government agents. The bicycle is a fast and silent mode of transport unimpeded by the usual vagaries of horses or weight of traffic. The club structure and current enthusiasm for the bicycle, the many informal and recreational journeys taken at all hours of the day, and even at night, are the perfect concealment for this activity. We don’t know who is organising this, it could be anyone, not necessarily even a member of the club, perhaps a relation or an associate, but the club is somehow at the centre of it. We know this because of a message intercepted by one of our agents, but the messenger himself could not or would not tell us any more except that he had been paid for his services in the usual way. We kept a watch on him, but he managed to elude us and we have not been able to trace his whereabouts.’

Frances was thoughtful. ‘I seem to recall reading that a member of the club was murdered last year.’

‘Yes, the club secretary Morton Vance. He was killed by a pig farmer who had a grudge against bicyclists.’

‘Do you think there was a connection between the murder and the traitorous activities?’

‘Naturally we considered it, but on the whole, we think not. The farmer, Sam Linnett, was an illiterate brute, and a thoroughly untrustworthy type. Not a man one could rely upon to keep secrets. A criminal agency wishing to conceal its activities would not employ him for choice, and there is no evidence that he was paid for what he did. As for Vance, we have made careful enquiries and discovered nothing against him. A member of a respectable family, he had no unsavoury associates, and left a modest estate all accounted for by his salary and a small inheritance.’

‘I see,’ said Frances. The murder and subsequent trial had been fully reported in the Bayswater Chronicle, and she resolved to refresh her memory on the subject when she returned home.

‘We have sent a male agent to join the club, and participate in its activities,’ the gentleman continued, ‘but it would be useful to have a lady present as she might learn something from conversation that a man might not. But don’t be deceived – the people concerned may appear reputable, but they will be ruthless and dangerous. For that reason you must not go alone. Take a small party of friends, and it must be composed of people you trust above all others. They, too, must be subject to the same rules as yourself. Quiet observation, no more. Reveal to them only that you are watching for criminal behaviour, although I understand that your associate Miss Smith knows more of your affairs than most. You must confide your true purpose to no one else.’

Frances was surprised. ‘Not even the police?’

His gaze hardened. ‘Most especially not the police, as we hope our mission will proceed without anyone suspecting what is occurring. If they should need to be informed, it is we who will take that decision, and not you.’

Frances sensed a difficulty. ‘These events attract a substantial crowd. What if I encounter someone who knows me, and guesses that I am there for work and not recreation? That is a possibility.’

‘We have every confidence that you will be able to deal with that eventuality.’

There was no point in contradicting him. ‘I suppose even a detective can enjoy a day of leisure. Very well, the first person I shall consult is a good friend who took up bicycling last spring, and is a member of the club. He assures everyone who he meets that it is the finest sport in the world. Often at some length – and in very great detail.’

The gentleman smiled. ‘Yes, we know. Mr Cedric Garton. He is your introduction to bicycling.’

‘Ah, now I see why you have offered this task to me.’ Frances’ mind inevitably drifted to a story she had read not long ago, a penny publication called Miss Dauntless Rides to Victory, by W. Grove, in which the valiant heroine had leaped onto a bicycle on which she had pursued and captured a criminal. Miss Dauntless was an invention of the writer, a lady detective who dared do all a man might do and far more. Some of Frances’ clients assumed that this fictional Amazon was a thinly disguised portrait of herself, and she was obliged to disabuse them of that belief very firmly. She might have been annoyed with Mr Grove, except for what had transpired at their one and only meeting. He had then been rather dashingly and mysteriously arrayed in a long black cloak and Venetian mask, and had proceeded to save her from certain death. So relieved was he to find that she was unhurt that he had then clasped her warmly in his arms, a familiarity which under the circumstances it would have been churlish for her to refuse. Frances could still recall the pleasing aroma of his Gentleman’s Premium Ivory Cleansing Soap. She wondered where he was now, and what he might be doing.

‘Miss Doughty?’

Frances realised that she had been daydreaming. ‘I’m sorry. I was thinking … I was thinking … er … do I need to learn to ride a bicycle?’

To her surprise the gentleman laughed gently. ‘Oh, dear me no. The bicycle is not for the female sex. Well, not unless they are persons of a certain kind – in a circus and therefore improperly dressed – or possibly French. Ladies, and older gentlemen, married gentlemen who do not wish to risk life and limb, prefer the tricycle, or indeed the ‘sociable’, that is a machine which permits two persons to ride side by side.’

‘Well that sounds very pleasant. I should like to see that.’

‘Then you accept the mission?’

‘I do.’

The gentleman had a folded newspaper under his arm, which he handed to Frances. ‘You will find the information you need in there.’

Frances took the newspaper. She knew better than to unfold it in public. There was an envelope lying between the pages and she would open it and study the contents when she was alone.

On the other side of the Serpentine music began to play, a lively tune emanating from the bandstand that nestled amongst the trees of Kensington Gardens.

‘I must leave you now,’ said the gentleman, rising to his feet and taking a packet of cheroots from his pocket. ‘I have one more word of advice. If you should meet a man called Gideon, he is your friend.’ He stuck a match and lit the cheroot. ‘We have never met. This conversation never happened.’ He walked away.

CHAPTER TWO

Dainty ladies who valued their pale complexions might have taken a cab home, but Frances, whose overly tall angular figure could never be thought dainty, liked the sunlight, and enjoyed a walk in fine weather. When her father, William Doughty, had been alive, and she had been little more than an unpaid servant in his chemist’s shop on Westbourne Grove, his extreme parsimony had required Frances to walk almost everywhere, and even now that she could afford to travel by cab, she often chose not to. Long walks cleared her mind, as well as exercising her body. A mystery that might have puzzled her as she sat by her own fireside could sometimes be brought to a clear and obvious solution as she walked. The worries and frustrations of daily life were eased by her brisk vigorous stride, and she would arrive home refreshed rather than weary.

After the gloom and distress of last autumn and winter, the warm weather had brought Frances a kind of rebirth. Weeks of suffering that might have crushed another person had only served to prove to her that she could endure terrible trials and they would not weaken her; in fact, in a way that she did not fully understand, she felt stronger than before.

In the spring she had at last shed the grey demi-mourning she had worn in memory of her father and older brother, and found new shades of quiet blue and subtle violet, restrained yet pleasing. Her mirror showed her a new woman, one who, while still very young, had a world of experience behind her eyes, and was eager for more. Not only had she healed and flourished, there lay in the deepest recesses of her mind another thought, a tantalising possibility that she could be better still, in ways that she was yet to discover.

The detective business was doing well. Frances tried to avoid fame and drama, although she was not always successful in this, especially since her natural curiosity and instinct to solve a puzzle prompted her to pursue enquiries even when unasked. Her clients, who included some of the most respectable denizens of Bayswater, valued her industry and discretion. She was careful, however, never to allow her portrait to appear in any publication. Her government missions made it imperative that her face was not widely known.

Frances had not encountered any cases of serious crime for some months. Small thefts, missing persons and pets, suspicious behaviour connected with love and marriage, disputes with neighbours; these were the humdrum events by which she earned her daily bread. Swiftly dealt with, usually without unhappy traces remaining. Sadly, one could rarely draw a line under felonies; catastrophes whose spreading stain of loss and shame reached determinedly into the future. Her work had left her with few enemies. Those criminals she had brought to justice had received the penalty of the law; others whom she merely suspected but whose guilt could not be proved had fled to new lives.

There was one remaining anxiety; the evil and malodorous criminal known as the Filleter due to his sharp knife and lack of restraint in using it. It was Frances who had apprehended him during the widespread terror in the autumn of 1881 caused by the horrible murders of the Bayswater Face-slasher, indeed for some time he had been suspected of actually being that shadowy figure. The Filleter had been confined at Paddington Green Police Station, but before he could be charged, a destructive storm had swept through London, and the station roof had collapsed into the cells. The prisoner, his body horribly crushed, was taken to hospital where he lay close to death for some weeks before his foul associates came to remove him. Months later, he remained too broken to prowl the streets, and in any case, Bayswater had become a little too dangerous for his liking. He was now, so Frances had been informed, conducting his nefarious business south of the Thames, where he controlled a youthful gang of criminals. If he held her responsible for his infirmity, and meant to exact his revenge, he would have agents who would know where to find her, and might be waiting their moment.

As Frances approached the exit from Hyde Park on that delightful afternoon she found the Italian water gardens more alluring than ever, and paused to admire them. The white marble urns gleamed in the sunlight, and the delicious spray of the fountains cooled the air. She had once been told that this beauty had been created by love, a gift to the Queen from Prince Albert, her adored and adoring consort. Frances, wondering if the Queen herself had stood on this very spot and found peace and pleasure, could not help but reflect on the Queen’s married happiness and how tragically it had been cut short. Was it better to be so beloved only to be left cruelly alone, or never to have found love at all?

Frances dismissed those difficult musings from her mind and walked on; all her wits would be needed when crossing the teeming thoroughfare of Bayswater Road. Safe at last in the shadow of the lofty white villas that faced the park, she devoted her thoughts to those she would ask to accompany her on her new mission. Happily, she had no difficulty in identifying her most trusted allies.

Sarah Smith had once been the Doughtys’ maid-of-all-work, when the family had lived in apartments above the chemist’s business on Westbourne Grove. More than that, however, she had been the closest female companion of Frances’ childhood, her friend, her support in times of trouble, and the nearest she had ever known to a sister. When Frances launched her career as a detective Sarah had proved to be both an invaluable assistant and strong right arm. She was the only one of Frances’ associates who was aware of the occasional government missions, and often felt concerned that she had not yet been asked to play a part, if only to ensure her friend’s safety. Brought up by the East London dockside as the only girl in a family of nine siblings, Sarah was forthright and practical, stood no nonsense from anyone, male or female, and seemed to fear nothing. Her brother Jeb, a boxer known as the Wapping Walloper, had been heard to say that if Sarah had ever gone into the ring, there were many men she might have left the worse for wear.

Cedric Garton was Frances’ near neighbour and friend, who lived in a beautifully decorated apartment with his faithful and attentive manservant, Joseph. Cedric had been born in Italy, where his family was engaged in the export of wine, but after visiting London for the inquest on his brother, a Bayswater art dealer, he had been obliged to remain to deal with the complicated issues that had arisen from that loss. Cedric liked to adopt the air of a languidly idle aesthete, which concealed a fine brain and a strong active physique. Bicycles were his new passion.

Tom Smith had once been the Doughty chemist shop’s delivery boy, and was said to be Sarah’s cousin. Frances had long suspected that the family relationship was far closer, and most probably the reason behind Sarah’s glowering contempt for most men, whom she liked to instruct, sometimes quite forcefully, on the correct way to treat women. Sarah would have been fourteen when he was born, the same as Tom’s present age, and as he grew to young manhood the resemblance between their facial features became increasingly obvious. An enterprising youth, Tom spent every waking moment considering how to make money, and had built up a thriving business, a message and delivery service known as ‘Tom Smith’s Men’, with nothing but hard work, dedication and careful conservation of his resources. He had a clear ambition in life, to own property, become very rich and marry Miss Pearl Montague, the niece of the chemist shop’s new owner. No member of Miss Montague’s family, least of all the enchanting maiden, suspected that she was the object of Tom’s silent and respectfully distant adoration. Tom, and anyone who knew him well, had no doubts that in time all his ambitions would be realised.

‘Ratty’ was the nickname of a fifteen-year-old boy who had spent much of his early life without a home following a family tragedy that had deprived him of his parents. He was Tom Smith’s best agent, and since meeting Frances had developed ambitions to become a detective. He currently assisted her enquiries, managing his own group of boys whose eyes and ears were all over Bayswater. Fast on his feet, Ratty knew West London as if he had an unrolled map in his head. His courage and initiative were beyond question.

For some months, Sarah had been walking out with Professor Pounder, the proprietor of a high-class sporting academy that taught the gentlemanly art of pugilism. Cedric exercised there, and regarded his instructor with considerable respect. Sarah had begun teaching female-only classes, demonstrating to Bayswater ladies how to exercise themselves for health and take care of their safety, preferably with a concealed weapon. It was there that Frances had learned the art of the Indian club, a practice of rhythmic manipulation that helped her strength and dexterity and brought peace to her mind in times of trouble. The Professor was tall, athletic, good-looking, calm and quietly spoken. His devotion to Sarah was tangible in a way that did not need to be expressed. Although Frances had not known him for long she could recognise that he was utterly dependable when any kind of danger was present. She also knew that for a man to earn Sarah’s trust he had to be truly exceptional.

Before plunging into the long terraces of Bayswater proper, Frances studied the traffic of cabs, carriages and delivery carts, and the surging mass of shiny-flanked labouring horses. In amongst them, daring and darting, were young men on bicycles. Now she thought about it, the bicycle was starting to appear on the London streets with increasing regularity. Barely four or five years ago one almost never saw a high-wheeled bicycle in town. It was a youthful novelty, and so fraught with risk that it was seen almost entirely as a countryside touring vehicle. The earlier invention, the velocipede, often referred to as a ‘boneshaker’ with, she had been assured, very good reason, was by comparison a heavier but slower and safer vehicle, whose wheels were more similar in size. Difficult to steer and a desperately uncomfortable ride on all but the smoothest of surfaces, it had nevertheless earned many dedicated adherents, principally for want of something better.

The velocipede, according to Cedric Garton, could never be the ultimate in wheeled rider-propelled vehicles. It had only ever been a promise of what might be possible in future. That future, Cedric had enthused, with all the verve of a recent convert, had come to its full flowering in the high-wheeler. It was fast, it was light, it was elegant, it was a beautiful design that brought pleasure to the senses and would last forever. There was the small matter of the danger of catching one’s legs in the handlebars when taking a header on a sudden stop – a not infrequent occurrence – but great minds were working on that difficulty, and in the meantime one could always drape one’s legs over the bars when running downhill.

The secret of the bicycle’s speed was the enormous front wheel, which quite dwarfed the trailing wheel, and could reach heights of sixty inches, the choice depending on the leg length of the rider. The recent innovation of tubular steel for many of its parts had resulted in a machine that was both strong and light, and skimmed along with ease.

Despite Cedric’s predictions, Frances could not imagine that bicycles could ever be truly useful in town, where riders balancing high on a slender wheel would have to try and steer a safe path between horse-drawn carriages, omnibuses and careless pedestrians. A stray dog, a stone or a nervous horse was all that was needed to cause a dreadful accident, and there had been several of late, resulting in grave injuries and even the deaths of both pedestrians and riders. It was unsurprising that from time to time bicyclists avoided muddy, crowded roads by taking to the pavement, much to the annoyance of those on foot. Newspapers were frequently bombarded with irate letters from citizens who declared bicycles to be a menace, and urged that they should be banned altogether. Occasionally frustrated waggoners would deliberately drive into bicyclists and knock them down.

On reaching Westbourne Grove, the vibrant heart of fashionable Bayswater and West London’s leading shopping promenade, Frances left a message for Tom and Ratty at the office of Tom Smith’s Men, and continued to Westbourne Park Road, where she left a similar message for Cedric Garton before taking the short walk to her home. Sarah had not yet returned, but was expected back for supper. Professor Pounder’s whereabouts would not be hard to discover since he lived in the ground floor apartment of the same house in which Frances and Sarah occupied the first floor. The Professor often joined the ladies for supper, although there were also evenings when Frances was left alone with her thoughts and her reading and Sarah and her beau kept company.

The top floor of the house was home to a spinster lady who was engaged in works of charity, but she had recently announced her intention of quitting London at the end of the month, and going to those parts of the country where she felt her energies could be better applied. The landlady, Mrs Embleton, was already looking for a new tenant. Frances could not help wondering if Mrs Embleton might be concerned that prospective tenants would be anxious about sharing an apartment house with a private detective and a professor of pugilism, a house, moreover, which had once been the scene of a violent death for which one of the occupants had been responsible. Mrs Embleton, although a kind and understanding lady, had seen a great deal of upset both in the house and immediately outside it since Frances had taken lodgings there, and more than once it had been touch and go as to whether the troublesome tenant might be asked to leave. Although Frances took great care never to be late with the rent, and had once been of service to Mrs Embleton in a small matter of some stolen washing, for which she had made no charge, she still felt her situation to be precarious.

Frances had therefore decided to put a suggestion to her landlady that Tom Smith and Ratty should take the upper lodgings. They had been living in cramped circumstances in a corner of their office space on Westbourne Grove, but the rapid and profitable expansion of their business had made this situation increasingly difficult. Tom was always looking for talented and hardworking boys to employ, and he often found them living on the street in miserable and unhealthy conditions. He offered them regular paid work, somewhere warm and safe to lay their heads, as much day-old bread as they could manage, and copious libations of hot tea. Now that their ablest lieutenant Dunnock had reached the advanced age of thirteen, he was considered mature enough to supervise the more junior agents in the absence of the main men. Tom and Ratty at last felt able to enjoy their success by luxuriating in their very own bachelor apartment, and were eager to move in.

Although Frances had been advised that the murder of a member of the Bayswater Bicycle Club in the previous year was not thought to be connected with the subject of her mission, she could not help but reflect on it, while reminding herself that this was one occasion when she did need to keep her curiosity in check. If she was to attend a race meeting, however, she ought first to find out all she could about the club, its members and its history. Frances was a close reader of the Bayswater Chronicle, copies of which she saved for reference, and determined that once she was home she would search her collection for the trial report. Still more than the murder of the unfortunate wheelman, however, there was something else on her mind, an insistent provoking little idea that no matter how hard she tried, she could not control.

In her own cool and quiet parlour she might have opened the large brown envelope she had been handed by the silver-haired gentleman she had officially never met at a meeting that had never happened, or brought out her editions of the Bayswater Chronicle, but instead she made a nice pot of tea and sat down to consult her copy of the penny story Miss Dauntless Rides to Victory by W. Grove. She had not misremembered it – that annoyingly impossible Miss Dauntless really had sprung valiantly onto a high-wheeler and not a velocipede, and bowled along the road like a champion racer in pursuit of her quarry. Unfortunately, the engraving on the front cover did not offer any clues as to how the redoubtable heroine had actually achieved this feat, as it only showed the top half of the lady’s unnecessarily buxom figure, and left the rest to the imagination. Now that Frances thought about it, from a practical point of view any woman who attempted to straddle such a vehicle would be unable to do so with any measure of decency or safety when encumbered by long heavy skirts and petticoats.

That conclusion ought to have been the end of any thoughts Frances might have entertained of learning to ride a bicycle, yet she remained unwilling to abandon the idea. She had noticed that Mr Grove’s stories sometimes seemed to hold messages for her. Sarah had suggested that they were really thinly disguised love notes, but Frances was sure that they were something more. Before Mr Grove had appeared before her in his rather fetching cloak and mask, he had written a story in which Miss Dauntless was romanced by a man clad in exactly that way. It was as if he was preparing her to recognise and trust him. Was this story of Miss Dauntless and the bicycle a suggestion that she should learn to ride? Or was it simply a challenge to her determination, energy and ingenuity, to see if she could overcome the obstacles? If so, it was a challenge Frances felt she would like to accept.

CHAPTER THREE

Frances finished her tea and opened the envelope she had received in confidence. It contained a map of East Acton and the surrounding area, the last quarterly newsletter of the Bayswater Bicycle Club, and a notice of the arrangements for the annual meeting. There was to be a special parade of new vehicles, a competition for the best turned-out bicycle, and a busy programme of races over varying distances and for all classes of riders. This included a contest reserved for professional wheelmen, a competition for boys, novices’ races, and a tricycle race for ladies. The prizes took the form of medals and cups generously donated by the club patron, Sir Hugo Daffin. The most sporting wheelman of the year, an award voted for by the committee, would have his name engraved on the Morton Vance memorial cup.

Frances frowned as she read that name, and then began to search back through her copies of the Bayswater Chronicle of 1881, which were stored in a neat pile on her dressing table. Since starting to keep her weekly issues for reference, she had accumulated some two years’ supply, a measure that had saved her many a visit to the newspaper offices on Westbourne Grove. Her growing library also included street directories, maps and timetables. She might have been anxious that the collection would eventually outgrow the space allocated in her bedroom, but since she owned few personal luxuries, that eventuality was still some way in the future.

Recalling that the trial of the young bicyclist’s killer had taken place at the Old Bailey during last year’s autumn session, she located the report without difficulty. Sam Linnett, aged forty-eight, a pig farmer of Old Oak Common Lane, East Acton, had been tried for the murder of twenty-seven-year-old Morton Vance, commercial clerk and secretary of the Bayswater Bicycle Club, who had been found battered to death the previous August.

Linnett, said the prosecution, was notorious for making unprovoked attacks on passing bicyclists, by cutting at them with a horsewhip or throwing stones. He had twice been arrested and appeared before the magistrates at Hammersmith Police Court, who had fined him for these offences. He was also in the habit of cutting staves from the hedgerows and leaving them lying in the path near the entrance to his farm, although there were no witnesses to him doing so. A horse, the learned gentleman pointed out for the benefit of the non-bicycling members of the jury, might pick its way neatly over such an obstruction, but a high-wheeler could be so unsettled, bouncing off the rough wood on its hard rubber tyres, that it would propel its rider violently to the ground, resulting in serious injury or even death. The court would hear from members of the Bayswater club who would testify that they had learned to be wary of Sam Linnett. Since the lane was the principal way between East Acton and the Uxbridge Road it was hard to avoid using it altogether. The club members had very sensibly placed a white-painted marker post as a warning to all riders that the farm entrance, which when approached from the north was partly concealed by a curve in the lane and overhanging hedgerows, was imminent. When wheelmen saw the marker post they knew to slow down and look out for potential danger, hoping not to encounter the irate pig-man. Some actually dismounted and walked past the farm entrance, wheeling their machines along, so as to be less vulnerable to attack, and any staves found lying in the road were picked up and thrown into the ditch.

That fatal afternoon, Morton Vance had been riding south down Old Oak Common Lane when he had collided with Sam Linnett’s high-sided livestock cart, which had been turning into the farmyard, creating an impassable barrier across the width of the narrow roadway. The accident, if that was what it was, had resulted in broken bones; however, according to the prosecution, Sam Linnett had then descended from his cart, picked up a discarded stave and murdered Morton Vance with two hard blows to the skull, after which he had calmly proceeded about his business as if nothing had happened.

The jurymen, wrote the Chronicle’s reporter, had looked on the accused with ill-concealed disgust. Sam Linnett had entered the dock in his stained workaday clothes, which in the warm, crowded and airless court exuded an eyewatering and stomach-turning reminder of his occupation. What appeared to be a permanent scowl was fixed to his face, although, said the Chronicle, it could not be determined whether this was evidence of how he felt about his unenviable position, or his everyday expression, revealing the monstrous character of the man.

Sam Linnett’s defence counsel did his best for his unprepossessing client, explaining that there were mitigating circumstances that had caused the farmer’s antagonism to bicyclists. A year earlier Linnett’s only son Jack, then aged sixteen, had been driving the pig cart when his horse had shied and bolted on encountering a passing bicycle. The cart had overturned, and crushed the boy’s leg. Although he had not lost the limb, he was now crippled for life. The defence gave a moving description of the fond father’s overwhelming grief at this tragedy, asserting that since then Linnett had become excited to the point of insanity, and possibly even beyond, at the mere sight of a bicycle. It was this misfortune that had led him to make the attacks with whip and stones, and lay the staves, all of which offences he freely admitted. Linnett had given up laying staves after being warned about it by the police, and he had not made any attacks after being fined. He still shook his fist when he saw a bicyclist go past, but that was wholly understandable and could hardly be counted as a crime. This did not mean that Linnett had killed Morton Vance, an act he strongly denied. He had no quarrel with Vance as a man. The rider who had caused young Jack’s calamity was not even a member of the Bayswater Bicycle Club. It was well known that he was a Mr Babbit of the Oakwood Bicycle Club, who, although he was not obliged to do so, had actually admitted some liability and paid the farmer a sum of money in compensation.

Sam Linnett, said the defence, made no secret of the fact that on the day of the fatality Morton Vance had collided with his cart; however, the accident had been entirely Vance’s fault. His client utterly denied that he had deliberately used his cart to obstruct the roadway. The young bicyclist, he stated, had been riding down the lane at a dangerous speed and would have been able to stop and avoid a collision had he been proceeding at a sensible pace. The young man was lying in the road, very much alive, when Linnett had last seen him. He had no duty of care over Vance, and therefore had no compunction in leaving him where he lay, assuming that his associates would shortly come and assist him. The speed of the bicycle had led him to believe that Vance was racing, and that another man would arrive very soon. He didn’t see another bicycle but then there was a slight bend in the road and some overhanging hedgerows just north of the farm, which would have hidden an approaching bicycle from his view.

Yes, Sam Linnett had abandoned a seriously injured man lying in the road, that much he admitted, but he had not killed Morton Vance. Another person, possibly a fellow bicyclist, must have arrived soon afterwards and committed the murder. The jurymen, according to the Chronicle, had narrowed their eyes sceptically at this unconvincing explanation.

There were several witnesses for the prosecution. Members of the bicycle club testified describing previous acts of violence towards bicyclists by Sam Linnett. Morton Vance, they said, was an excellent young man, a hard-working club secretary, who had not had a falling out with anyone. Particularly distressed in the witness box was fellow bicyclist Henry Ross-Fielder, who had discovered the body of his friend. There had been no doubt in his mind that Vance had already breathed his last and was beyond any help. He had known better than to appeal to the Linnetts for assistance in removing the body and had ridden to East Acton as fast as he could to get a carrier.

A surgeon, a Mr Jepson of Acton Town, who had examined the body, confirmed that Vance had died from blows to the head inflicted by some hard object. The collision with the cart would not have caused those injuries or been fatal. A stave found lying in the roadway was stained with blood, and hair resembling Vance’s was sticking to it. He had no doubt that this was the murder weapon. He had also examined Linnett’s pig cart and there were marks on it that looked as if they had been made by a recent collision with another vehicle. The bicycle, which was painted dark blue, was damaged, and he had found flakes of the same coloured paint on the pig cart.

Jack Linnett was called to give evidence and there were gasps of surprise and sighs of pity for the fine-looking youth who limped to the witness box on a twisted leg. His working clothes were rough but clean and well mended, and he did not bring the odour of the farmyard into the court with him. Many of the onlookers, including the Chronicle’s correspondent, found it hard to believe that this was the true offspring of the surly degenerate in the dock. The young man’s evidence, given quietly and with due respect to the court, was oddly unhelpful to either side. He said that he had not witnessed the accident, but recalled his father bringing the cart home on the day of the murder. Sam Linnett had mentioned only that a bicyclist had been racing down the lane and collided with the cart, but he had made no further comment, and had simply gone about his work and eaten his dinner as usual.

Even without the reporter’s embellishments, Frances could imagine how well the pig-man’s defence had been received in court. While the accused deserved some sympathy for his son’s circumstances, and had in all probability acted in the heat of the moment, nevertheless he had a record of assaulting men who had had nothing to do with the accident involving his son and had unashamedly admitted his disgracefully callous behaviour towards a badly injured man.

The jury had taken several hours to reach a verdict and finally declared Sam Linnett guilty of murder, with a recommendation to mercy. That mercy had been denied, and Sam Linnett had gone to the gallows.

CHAPTER FOUR

There was one name in the trial record that was familiar to Frances, since she was sure she had seen it in the newspapers quite recently. She looked back through her copies of the Chronicle and found the trial of Robert Coote, unemployed, aged twenty-five. Some two months ago, Coote had been found guilty of aggravated assault causing actual bodily harm in a public place against the Reverend Duncan Ross-Fielder of Holland Park and resisting arrest, resulting in minor injuries to Police Constable Gordon. Although the Christian names differed and the clerical victim of the assault could not therefore have been the same man who found the body of Morton Vance, the unusual surname and the Holland Park location, not far from East Acton, suggested to Frances that the two were related.

Unusually, Coote had asked for permission to make a statement to the court. On learning of this request, his counsel had asked for time to consult with his client in private, and this had delayed the hearing by several minutes. When counsel and prisoner returned to the courtroom it was apparent from the strained manner of both men that there had been a heated exchange of words. Observers inferred that Coote’s own defence had strongly advised him against making the statement. In the event, the court had denied the request. The nature of the statement remained a mystery, although it was rumoured that the prisoner was intending to make accusations against his victim that could not be substantiated, and counsel must have felt that this would hinder rather than assist his case. For the remainder of the trial, Coote stood silently in the dock, his mouth twitching with the words he wanted to be heard.

There were several witnesses to the crime. Coote had been seen lurking in the street near to Ross-Fielder’s home for at least an hour before the assault. He had not attempted to beg from anyone else, but on seeing the reverend gentleman he had approached him with urgent demands for money. When this request was refused in the mildest of terms, he had then launched an unprovoked attack. The respected clergyman, aged fifty-three, had been punched, pushed to the ground and kicked violently. Several witnesses had cried out for help, and Constable Gordon, who had come running to the reverend’s aid, had also been assaulted. A second policeman had been required to secure the struggling, abusive prisoner and remove him to the police station.

Coote, said the prosecution, had never previously met or been employed by Ross-Fielder, although he had recently been annoying him with a spate of barely literate letters asking for money. It was thought that he had made the clergyman a target of his demands because his victim was a man of honour, well known in West London for his service on a number of charitable bodies, and who gave alms by private donation.

The defence could only say in mitigation that his client was in straitened financial circumstances having lost his employment as a parcel carrier through no fault of his own. He was also distressed by the recent death of his widowed mother. He had come to court alone, and had no friends or family to assist and support him. Coote had freely admitted that he had written to the clergyman asking for money, and on receiving no reply had approached him in the street to beg assistance. When the reverend had instead directed him to an appropriate charity, he had been upset, and had simply lost his temper.

Had the incident occurred between two drinkers in a beer house, Coote might have been consigned to prison for six months, but violence towards both a clergyman and a policeman were more than the judge could stomach, and with many harsh words he sentenced Coote to eighteen months with hard labour.

As Frances waited and made her plans, her associates gathered. First to arrive was Sarah, who, once she knew what was proposed, quickly arranged a hearty supper of bread and butter with cold meat, cheese, pickles, hardboiled eggs and tomatoes, and sent the maid out to fetch strawberry tarts. Professor Pounder, who was next, was immediately deputed to bring bottled beer and cordials.

Cedric Garton arrived in lively form, freshly shaved and cologned, dressed in the newest and most fashionable gentleman’s apparel with a flower in his buttonhole and eagerly enquiring why he had been summoned by Bayswater’s finest detective. Tom and Ratty soon followed. Everyone assembled around the parlour table, piled their plates with food, helped themselves to their chosen beverages, and gazed at Frances expectantly.

‘I have been asked to undertake a mission,’ said Frances, nibbling the edge of a crusty slice with care, so as not to interfere with her address, ‘and it is a very simple one, but one which may potentially have some danger attached to it. I have therefore been advised that for safety I should be accompanied by those people I trust most.’ She looked about her and smiled. ‘And here you all are, my dearest friends and associates, those who I know to be brave and clever and honest. My task will be undertaken while spending a delightful day out in East Acton for the annual summer race meeting of the Bayswater Bicycle Club.’

‘My word!’ exclaimed Cedric, almost dropping a neatly constructed sandwich of cold chicken. ‘Well that won’t be hard for me, as I am to attend that event myself. I am entered for the two-mile handicap, and the competition for the best turned-out machine. But what is your mission? Are you permitted to reveal the identity of the client?’

Frances had given a great deal of thought to how much she could reveal. ‘All I am allowed to say is that my task is simply to observe my surroundings and take note of anything that might strike me as unusual. That may seem very simple, but it requires unceasing vigilance, and I am instructed to be very careful to do nothing adventurous that might attract attention.

‘Mr Garton, your advice would be extremely valuable. I would like to learn all you know about the club and its members. It would be a very great help if you made a list of the gentlemen’s names with notes of anything you know about them. You can include their friends and family too, if you have any information. But please, and this is very important, you must not ask any questions. If you make special enquiries of your own you might reveal too much in the wrong quarters.’

Cedric gazed at her enquiringly. ‘And now I am more than a little concerned; not for myself, but for you. What, exactly, are the wrong quarters?’

‘That, unfortunately, is the one thing I don’t know, which explains the potential for danger. We can’t tell who our friends and enemies are.’ Apart, she thought, from the mysterious Gideon mentioned by the gentleman with silver hair. ‘We must trust each other, of course, but we trust no one else. So you must assemble that list from memory alone.’

‘You are stretching the capacity of my poor brain again,’ sighed Cedric, smoothing his already smooth blond hair, ‘but of course, for you, dear lady, as always I will do my best.’

‘So there’ll be dangerous types there?’ asked Sarah, with an anticipatory glint in her eye.

‘Possibly.’

Sarah cracked her knuckles. ‘We can deal with them.’

Professor Pounder said nothing but he glanced at Sarah, and his expression spoke for him.

‘But suspicious persons are not to be approached,’ warned Frances. ‘That rule is for us all. Should there be any hint of actual danger I am under strict instructions to leave at once.’

Cedric nodded approvingly. ‘We’ll keep you safe, have no fear!’

‘That nasty Filleter won’t be there, I hope?’ said Sarah, wrinkling her nose with disgust.

‘I doubt it,’ said Frances. ‘Even if he could be, and I understand that nowadays he is unable to walk unaided, he is a crude individual and this is a different matter altogether.’

‘That filthy fellow would be spotted at once and thrown out of any sporting event,’ declared Cedric. ‘His picture was in all the illustrated papers last autumn, and I for one have made it my business to study his image and look out for him. I can promise you he has not been in Bayswater again, for which we can all be thankful.’

‘But he will have agents,’ said Frances, ‘and they will be no better than he.’ She glanced enquiringly at Tom and Ratty, who exchanged looks. Tom shook his head and swallowed a mouthful of cheese and pickle. ‘Nah. We ain’t seen ’im. An’ if ’e’s got men, we ain’t seen ’em, either.’

‘I find it hard to believe that any of the club members are involved in crime,’ Cedric continued. ‘They all seem such decent sorts.’

‘How many members are there?’

‘About a dozen or so I think. We meet up once a week for a club ride, and there are race meetings in clement weather and the most delightful social events in the winter.’

‘Tell me about the patron, Sir Hugo Daffin.’

Cedric wielded a napkin with dexterity. ‘Oh, he’s a splendid fellow, must be sixty-five if he’s a day, but he still rides around the village on his bicycle. We have suggested that he might be better advised to take up the tricycle but he’ll have none of it. It’s thought he must have been on two wheels since the days of the dandy-horse. He lives at Springfield Lodge in East Acton and the club uses his rooms to meet, and he has visiting wheelmen to stay when they are touring. He’s dedicated to improving the lot of bicyclists and is forever patenting new inventions.’

‘What kind of inventions?’ asked Frances, scenting the possibility of work that might make the inventor the target of thieves.