5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

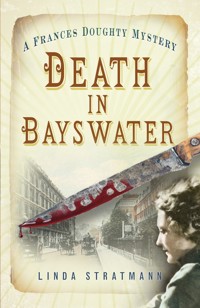

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Frances Doughty is a young sleuth on her first professional case, trying to discover who distributed dangerously feminist pamphlets to the girls of the Bayswater Academy for the Education of Young Ladies. Armed with only her wits, courage and determination, she finds that even the most respectable denizens of Bayswater have something to hide, and what begins as a simple task soon becomes a case of murder. As election fever erupts and the formidable ladies of the Bayswater Women's Suffrage Society swing into action, Frances' enquiries expose lies, more murders and a long-concealed scandal, and she makes a powerful new friend. The second book in the popular Frances Doughty Mystery series.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

To

Nige, Sabine, Karen and Simon

Because four Furlongs always go the extra half mile

CHAPTER ONE

Algernon Fiske was a very worried man. For some years he had been accustomed to living in the state of pleasurable equilibrium to which he felt he should be entitled, but suddenly all had been thrown into anxiety and confusion.

His late father had been a successful grocer, and while Mr Fiske would have been the first to state that grocers were splendid fellows he had declined to become one himself. The rent of several shops had enabled him to subsist on his true passion, English literature, and he enjoyed a modest celebrity as an author, lecturer and reviewer of books. His interests were especially directed towards the education of the impressionable young, and since he was the father of two girls he was particularly concerned with the prudent development of the female brain. His wife Edith was the daughter of a clergyman, whom he had selected not for love or beauty or fortune but for her good temper and the excellence of her mind.

A woman’s intellect was, he believed, too often neglected. Was it not the duty of womankind to conduct the management of the home, that haven of comfort so essential to the successful man? And while a nursemaid was more than adequate to tend to the bodily comforts of the very young, it was to their mother that they should turn for stimulation of the mind during their tenderest years. As he watched his infant daughters, Charlotte and Sophia, grow into sturdy and serious little girls, he began to wonder what school might be best for their development into the young women he hoped they would become, and lighted upon a small but promising establishment whose proprietors, Professor Edward Venn and his wife Honoria, appeared to be suitable in almost every way. The only small drawback was the Professor’s delicate state of health, which ill-equipped him for the burden of administration. Thus it was that Algernon Fiske MA became patron and governor of the Bayswater Academy for the Education of Young Ladies. He was soon joined by two other gentlemen with similar concerns, landowner Roderick Matthews, whose market gardens supplied the denizens of Bayswater with fruit, vegetables and fresh flowers, and Bartholomew Paskall, property agent. Under their guidance the little school moved to a larger establishment in respectable but not showy Chepstow Place and opened its doors to more pupils, the carefully brought up daughters of Bayswater gentlemen of substance. The unfortunate early death of Professor Venn, whose long hours of toil on a great work of history was both a fine example to society and his downfall, might have threatened the future of the school, but Mrs Venn had bravely stepped into his place. In all its years of existence there had been no suggestion that the school was anything other than the most perfect of its kind. This was the situation until the afternoon of Wednesday, 3rd March 1880, when fourteen-year-old Charlotte Fiske was unexpectedly escorted home by one of her teachers in a state of great distress.

Miss Bell (grammar, spelling and elocution) was quick to reassure the Fiskes that their daughter had done nothing wrong. That morning, Charlotte had discovered an item of printed matter in her desk that appeared to have been placed there by a prankster, but, being a sensitive girl, she had been upset by the incident and the school had thought it advisable that she return home for the afternoon to be comforted by her family. Edith Fiske was a shrewd woman who felt sure that Miss Bell, who loved the English language so much that she normally put it to constant use, was keeping something back. She ordered her cook to prepare a glass of warm milk, and as Charlotte sipped the soothing liquid, she carefully questioned her daughter.

‘Well, my dear?’ asked Algernon, a few minutes later, peering over his spectacles as his wife entered his study. There was a book of poetry on the desk before him. He had been struggling to compose a review and was trying to determine whether it was a greater kindness to the author to say only what good there was in his work, or tell him the truth and risk hurting his feelings.

‘It is both better and worse than I had feared,’ said Edith. ‘Charlotte assures me that she read very little of the offending item, but it was enough to learn that it was a treatise attempting to persuade young girls that they ought not to marry.’

‘Ought not to marry!’ exclaimed Algernon, astounded. ‘On what grounds?’

‘Thankfully,’ said Edith, dryly, ‘Charlotte did not read sufficient to discover that.’

Fiske threw aside his pen. ‘But why would anyone send our daughter such a thing? I hope she has taken no notice of what it says.’

‘She will not,’ said Edith. ‘You may leave that to me. But you, Algy dear, must go to the school at once and speak to Mrs Venn. The person who did this must be found and stopped. Who knows what wickedness they may commit in future?’

Algernon sighed and looked down at his barely commenced review of the works of aspiring poet Augustus Mellifloe, a task that had suddenly acquired more relish, especially in view of the keen wind making hollow mocking sounds down the chimney.

‘Don’t worry, my dear,’ said Edith, briskly. ‘I will deal with Mr Mellifloe. And remember to wear your muffler.’ Resignedly, Fiske rose from his desk. Edith took his place, selected a pen, tested the sharpness of its nib, and set to work.

Fiske returned home an hour later, his face grey with misery, and sank into an armchair. ‘The whole school has been under the most hideous attack!’ he exclaimed. Edith had, in his absence, completed the review to her satisfaction, although not, in all probability, to the satisfaction of Mr Mellifloe, and was stitching a lace edging to a new cap while simultaneously reading a book on English history, achieving this feat with a device of her own invention which held the pages of the volume open as she worked. She now abandoned both activities to give her unhappy husband her full attention and pour him a warming glass of sherry.

Fiske had learned that the morning class, which consisted of twelve girls, had assembled in the schoolroom to do an hour of quiet study on whatever subjects had been individually assigned. When Charlotte Fiske opened her arithmetic book a piece of folded paper had fluttered out. She had begun to read it when Miss Baverstock (music, deportment and dancing) who had been supervising the class, noticed the paper and investigated. Miss Baverstock decided to take Charlotte and the paper to see Mrs Venn (headmistress, history and geography) when a horrid thought struck her. She quickly ordered all the other girls to go up to the common room, and arranged for Mlle Girard (French, and plain and fancy needlework) to supervise them.

Mrs Venn, having perused the paper with understandable distaste, and establishing that Charlotte had no knowledge of how it had arrived in her desk, at once comprehended Miss Baverstock’s way of thinking and both women went down to the empty schoolroom, leaving Charlotte to be comforted by Miss Bell. Every desk was opened and thoroughly searched, and in every one there was an identical paper, each one neatly tucked into the pages of a book. Mrs Venn then set about interviewing all the girls individually, but none of them had as yet discovered the pamphlets placed in their desks or had any idea how they might have come to be there. Mrs Venn concluded that it was merely chance that it had been Charlotte Fiske who had been the first to find hers.

‘And what was your opinion of the item in question?’ asked Edith.

‘I did not see it myself,’ confessed her husband, ‘but I am told that it has been most carefully removed from innocent eyes. One hopes that it will never be seen again.’

Edith frowned and returned to her sewing. ‘What does Mrs Venn propose to do?’ she asked.

Fiske hesitated. Everything had been so very clear when he had spoken to the headmistress, but now, having to explain the position to his wife, he found it less easy to justify. ‘It is my understanding that she considers no further action to be necessary.’

Edith raised an eyebrow. ‘That is very surprising,’ she said.

‘She believes that the whole incident may have been no more than a childish mischief, the culprit being one of the girls who would not have understood the meaning of the publication,’ said Fiske. ‘Having spoken most firmly to all the pupils, she is convinced that the girl, whoever she may be, is now so thoroughly frightened by what she has done that she regrets her transgression and it will not recur.’

‘And do you share this view?’ asked Edith. There was something subtle in her tone that her husband could not help but find alarming.

‘I would like to,’ he said, hopefully.

Edith stopped sewing and looked at him with a direct stare that was all too familiar. ‘But you are understandably afraid that she may be mistaken.’

He sighed. ‘Supposing it is no thoughtless prank, but a plot by strident mannish women to affect the minds of our girls?’

‘Then,’ she informed him, ‘you must be concerned that such a thing may happen again.’

‘I am,’ he said unhappily.

‘And who knows what indecent material they may select for their next attempt?’

Fiske shuddered. ‘I wish I knew what to do.’

‘Mr Paskall and Mr Matthews both have daughters at the school,’ Edith observed. ‘It would seem appropriate to advise them of the situation.’

‘Yes! Yes of course!’ Fiske rose from his chair. ‘I will go and see them at once. In fact, I will call a meeting – an extraordinary meeting of the governors. This thing must be stopped. Our girls must be protected at all costs!’ He was visibly trembling as he left the room. Edith nodded approval, took up her scissors and cut a thread.

Later that evening Mr Fiske sat dejectedly in Bartholomew Paskall’s study in company with Mr Paskall and Roderick Matthews. The three men, although all in their late forties and joined in a common purpose, were remarkably unalike: Mr Fiske, short, slightly portly, with greying side whiskers and a thinning pate; Matthews, tall with a broad forehead, glossy dark hair and trim beard, drawing languidly on a cigar, Paskall, thin and intense with a nose like an eagle’s beak. While Fiske’s study was warmly lined with the leather backs of lovingly bound volumes, and Matthews’ spoke more of leisure than work, Paskall’s was an extension of his business, the shelves stuffed with cracked ledgers and bundles of papers tied with string. The desk was piled high with newspapers and political pamphlets, since Paskall, to his considerable pride, had recently been selected as one of the two Conservative candidates for Marylebone in the forthcoming General Election. Those with their fingers on the parliamentary pulse confidently predicted that this would take place in the autumn.

‘Of course you were right to alert us, Fiske,’ said Matthews, whose two youngest daughters Amelia and Dorothea and a ward, Wilhelmina, were all pupils of the school, ‘and right too to get the whole story from Mrs Venn. But the question is, what’s to be done?’

‘I don’t think this is a childish prank,’ said Paskall, frowning. ‘And neither do I think it is some confederation of women who may be easily dismissed as misguided. It is more serious than that. It is a personal attack on me. I have political enemies, and the success of the Conservatives in the recent by-elections makes my victory in the autumn almost certain. Someone seeks to destroy me by creating a scandal in the school. Of course I am concerned for my daughters, but Beatrice and Leticia are sensible girls and they will listen to me.’

‘Oh, I don’t smell politics in this,’ said Matthews, nonchalantly. ‘It could be some rival school about to open its doors and hoping to gain pupils by discrediting us.’

‘One thing we dare not do is make a public statement,’ said Fiske. ‘To deny wrongdoing would simply arouse suspicion where there was none before. Neither should we have anything to do with the police.’

‘I doubt they’d be interested, Fiske,’ said Matthews dismissively. ‘From what you say it isn’t even a crime.’

‘Can you imagine if anyone were to see policemen going into the school?’ said Paskall, his voice faint with horror. ‘And as for detectives—’

‘I would never condone persons of that sort speaking to our girls,’ said Fiske. ‘These men are in daily contact with the lowest type of criminals, and some of them are little better than criminals themselves. Many have actually been dismissed from the police force, for what reasons I dread to imagine.’

For a moment or two the only sound in the room was that of Matthews sucking at his cigar and a squally wind rattling the window and driving raindrops against the pane like pebbles.

‘Why not ask Mrs Venn to make enquiries?’ suggested Fiske. ‘She is a sensible woman.’

‘From what you have told us, Mrs Venn prefers that no enquiries should be made,’ said Paskall. ‘I agree that we should appoint someone, but it should be an individual with no involvement in the work of the school.’

‘What about a female detective?’ said Matthews with a laugh, which quickly evaporated when he realised that his two associates had taken his joke seriously.

‘Is such a person entirely respectable?’ asked Fiske. ‘It seems a very strange sort of proceeding for a woman.’

Paskall suddenly pulled a recent copy of the Bayswater Chronicle from the pile of newspapers on his desk. ‘Did you hear about Miss Doughty, the chemist’s daughter?’ he asked, and turned to the inner page of local news. ‘Reading between the lines she danced rings round the police and it is she we must thank for solving the murder of Mr Garton.’ He proffered the paper to the others and they examined a column headed ‘My Remarkable Career by a Lady Detective.’

‘What do you suggest?’ asked Fiske when he had read the item.

‘It can do no harm to engage her to look into the matter,’ said Paskall. ‘If the young lady can unmask murderers then I think she will be equal to this. The family is respectable, and I understand that her reputation is beyond reproach.’

Matthews put down his cigar and looked around for the brandy. ‘Agreed,’ he said, and somehow – and Mr Fiske never learned how – it was all settled in a moment that he should go to the chemist shop in Westbourne Grove and engage Frances Doughty as a detective.

The next morning Mr Fiske was unsurprised to discover that after the recent tragedies and charges of murder which had centred around Doughty’s chemist shop, the business was under new management. The shop was bustling with ladies, all casting simpering looks at the new young pharmacist Mr Jacobs, from whom he learned that Miss Doughty had not yet vacated the apartments next door. There, he presented his card to the maid-servant, a burly young woman with a face like a disgruntled bulldog, and was shown upstairs to a parlour, almost bereft of comforts, a large box suggesting that arrangements were being made to move to new accommodation.

Miss Doughty was very young, scarcely old enough to have left school herself, but that, to Mr Fiske’s mind, was to her advantage, as she might thereby gain the confidence of the girls. He was impressed by her calmness and composure, and as she listened to him, saw that she was already considering the difficulty and how she might resolve it. There was no hint of frivolity about Miss Doughty, no trace of unwarranted ornament or vanity, or a mind distracted by thoughts of romance. Miss Doughty would never have put a flower in her bonnet and made eyes at Mr Jacobs. Fiske departed, feeling a new confidence.

Frances was left alone for a while, and despite her cool exterior, her heart was thudding with excitement. Only an hour before she had been facing the dull but not unpleasant prospect of becoming a dependent of her Uncle Cornelius, a kindly man who she knew would attend to her comfort and happiness. Her main regret had been that Cornelius had no place for her maid, Sarah, who had been a quietly loyal and steadfast presence in her life for the last ten years. Sarah had first come to the Doughtys as a squat fifteen year old with an expression of deep gloom and the capacity for ungrudging hard work, and had become someone in whom Frances placed a confidence and trust that she would have shared only with a mother or sister. Cornelius had recommended Sarah to a family in Maida Vale, something Frances was still gathering the courage to mention, as she suspected that Sarah’s feelings on the subject were even stronger than her own.

Mr Fiske’s request had startled her, but it had opened a window that afforded her a view of a quite different future, and she had been bold enough to accept. Now that she had done so, doubts came crowding in and she took a clean scrap of paper and began to calculate how they might live. She had a little money left after paying her father’s debts, and Mr Fiske had been kind enough to advance her some funds for expenses. Against that she had to set the cost of lodgings and other necessaries. Her conclusion was that she had a month to achieve success. Even if this engagement proved to be her only one, it would be an adventure, and she reassured herself that at the end of a month she would be very little poorer than at present.

She was so engrossed in her task that she did not see Sarah approach until a substantial shadow fell upon the paper.

‘You won’t send me away, will you?’ said Sarah. ‘I’ll work for nothing. I’ll do extra washing and cleaning, it won’t be any trouble.’

Frances smiled reassurance. ‘I hope it will never come to that,’ she said. ‘No, it seems that I must hang out my shingle as a private detective.’

‘Oh!’ exclaimed Sarah, relieved. ‘Only I thought the gentleman might have come about —,’ she rubbed her broad red hands on her apron. ‘Because I wouldn’t have gone away and left you and there’s no one could have made me, so there!’ She pondered this new development and a smile spread across her face. ‘A detective!’ she said. ‘And you’ll be the best one in London – or in the world – which is about the same thing, really.’

‘But the best news is, I am being well paid for the work, and will be able to rent accommodation once we leave here. I must write to my uncle at once and advise him that I will not after all be taking advantage of his kindness.’ Frances had already decided to inform Cornelius that she was about to be employed by a girls’ school, which was very nearly the truth. Not long ago she would have hesitated about telling even a small untruth, but that time was past. She was becoming more practised at gentle deceit, something she felt sure would be a useful skill in her new calling.

‘There are lots of very respectable apartments to let hereabouts,’ said Sarah. ‘Only —,’ a new concern clouded her features, ‘they mostly have a housekeeper, and a washerwoman that calls, and I don’t suppose you’ll need a maid of all work.’

‘That is true,’ said Frances, ‘but what I will need is a lady companion on whom I know I can rely. Perhaps you might apply for the position?’

‘I’d like nothing better!’ was the eager response.

‘Then that is settled, and without the need for an advertisement.’

After fortifying themselves with tea and bread and butter, the two women set about their errands, Sarah to view apartments and Frances to undertake her first visit to the Bayswater Academy for the Education of Young Ladies, where Mr Fiske had preceded her to make an appointment.

The school occupied a single-fronted premises, with a ground floor, commodious basement and two upper storeys. Neatly kept, it nestled amongst the homes of professional gentlemen and elderly persons of the middle classes who enjoyed comfortable annuities. As Frances rang the bell, she wondered briefly if she was equal to her appointed task, but she pushed the thought aside, and determined that necessity would lend her whatever resources of skill and character she needed. After all, she thought reassuringly, with this inquiry she would not be required to solve a murder.

CHAPTER TWO

The door was opened by a diminutive maidservant with a pointed chin, sharp nose, sparkling eyes and more bounce in her manner than Frances would have thought appropriate.

‘Miss Doughty to see Mrs Venn,’ said Frances.

‘You’re expected,’ said the maid tartly. ‘Follow me.’

Frances, realising that her position in the house ranked just a fraction above tradesperson, entered a narrow high-ceilinged hallway, the walls adorned with botanical prints and pastel-shaded maps, and followed the maid up a flight of stairs to a heavy polished door, the brass plate announcing ‘Mrs H. Venn, Headmistress’.

As Frances was ushered into the study, the headmistress rose to meet her with a coolness of manner which was more than mere formality. Frances recognised at once to her considerable dismay that she was not wanted there, and the tight-lipped politeness of Mrs Venn’s greeting only confirmed that impression. She realised with some concern that when Mr Fiske had engaged her he had almost certainly done so without previously consulting Mrs Venn, something the lady could only have seen as a personal affront.

Mrs Venn was a lady of more than middle height and aged about forty-five. Her carriage was dignified without being unnaturally rigid, her air that of confidence in her own domain. She wore a plain costume of stout dark cloth with a bunch of keys at her waist, a fob watch on a chain about her neck, and a discreet mourning brooch at her throat. Her hair, once pale brown, now streaked with grey, was swept into a high knot. She had never been beautiful, but the approach of the middle time of life had lent her a poise that was not unflattering.

The study was small and well lined with books and ledgers, the desk neither too cluttered, which would have indicated a disordered mind, nor too bare, which would have suggested idleness. Everything was tidily arranged, and Frances felt sure that Mrs Venn would be able to lay her hand on any document required at a moment’s notice. There was a small, framed portrait on the wall, a painting in oils of a gentleman with bushy brows and a wide mouth with a pendulous lower lip that gave him a mournful if eccentrically intelligent look. Frances suspected that this was the late Professor Venn. There was also, very prominently displayed, a photograph of the front of the school building, with a group of three gentlemen – one of whom Frances recognised as Mr Fiske – standing on the steps handing a key to the Professor, with Mrs Venn a decorous shadow at his side. Of the other two gentlemen, whom Frances assumed were Fiske’s fellow governors, one was tall with a proud handsome face, while the other had a less flattering profile. Behind them was a small group of demure and identically dressed schoolgirls.

‘I must apologise for this intrusion,’ Frances began, in what she hoped was a suitably mollifying tone. ‘It is my intention to carry out what I have been asked to do with the least possible disruption to the work of the school.’

If there was a softening of Mrs Venn’s expression, the device that could have measured it had not yet been constructed. ‘Since the governors have appointed you to make enquiries, I will of course extend my full co-operation to enable you to complete them speedily,’ said the headmistress, in a voice that could have attracted frost. ‘My own opinion is that the whole matter is a trivial, childish piece of mischief, best forgotten.’

‘That is my thought exactly,’ said Frances, deeming it best to start by agreeing as far as possible with whatever the headmistress might say. Mrs Venn waved her to a seat and Frances took out her notebook and pencil, while Mrs Venn resumed her place behind the desk and sat in almost regal pose, her hands clasped comfortably before her. ‘I would like to begin by seeing a copy of the pamphlet.’

‘I am afraid that is not possible,’ said Mrs Venn.

Frances smiled. ‘I know that I am very young, but I will do my best not to be shocked by its contents.’

‘I meant,’ said Mrs Venn, ‘that they have been destroyed. On finding them my one thought was to protect my girls. Had I known that the governors would appoint someone to look into the matter I would of course have retained one for you to see.’

‘Well, that is a setback,’ Frances admitted, ‘but I am sure I will find a copy elsewhere. In the meantime could you tell me as much as you can remember about it – the title and the author – the publisher?’

‘I did not make a note of the publisher,’ said Mrs Venn. ‘I doubt if a respectable establishment was employed. It was an unpleasant, cheap thing, little more than a page folded in two and the interior printed. The title was something like “Why Marry?”, or some such nonsense. The author did not have the courage to provide a name.’

‘And the object of the pamphlet was to persuade girls not to marry?’

‘It appeared so. The entire tenor was most objectionable.’

Frances made a note in her book. ‘Can you recall any of its content?’

‘Miss Doughty, I have better employment for my mind than memorising material fit only for the fireplace.’ Mrs Venn gave a tilt of the chin that told Frances that she had now said all she would say on that subject.

A chart on the wall was a boldly lettered timetable of lessons, and Frances rose and studied it carefully. ‘I understand that Charlotte Fiske discovered the pamphlet in her arithmetic book at approximately nine o’clock yesterday morning. According to this timetable, the last time she would without doubt have opened that book was in a lesson which was held the previous morning between eleven and twelve o’clock. If the pamphlet had been there then, she would have seen it, so it must have been placed there between those times. I will need to interview Charlotte, of course, but I will also require a list of all persons who were in the school between those hours, and a copy of this timetable. I will also need to see the schoolroom.’

Mrs Venn’s expression did not change, but the fingers of one hand tapped on the back of the other in a small gesture of annoyance. ‘Very well,’ she said at last, taking a copy of the timetable from her desk drawer and handing it to Frances. ‘I will compose a list for you of all pupils, teaching staff and servants. I do not, of course, know what callers there were at the servants’ entrance, you must speak to the housemaid Matilda about that. I received three visitors on the afternoon of March 2nd. Mr Julius Sandcourt, the husband of a former pupil, came at two o’clock to discuss his desire to invest in the future of the school. He was here for about half an hour. Mrs Sandcourt is the eldest daughter of Mr Roderick Matthews, one of the governors. I then received a visit from Mr Fiske, with whom you are already acquainted, and he brought with him a Mr Miggs, who is establishing a new business publishing educational books. They wish me to write a book about the instruction of girls. They were here between four and five o’clock and took tea. I think we may assume that none of these visitors wish any harm either to the school or its pupils.’

‘I agree,’ said Frances, although she added all those names together with that of the third governor, Mr Paskall, to the list of people to whom she might speak. Even if someone was not a suspect, she thought their knowledge of the school might provide an insight which would lead to the culprit. ‘How long have the servants been with the school?’

‘I have no reason to suspect their involvement, if that is what you mean,’ said Mrs Venn. ‘The housemaid, Matilda, has been with us since the school opened, some ten years ago. She is due to be married very soon, and has every expectation of happiness. Mrs Robson, the cook, has been with us for seven years. Her husband, of whom I understand she has no complaint, is a coachman and they reside in Porchester Mews. Mrs Thorn, a widow, comes in to help with the cleaning twice a week, on Mondays and Fridays, as she has done for a similar length of time.’

Frances wrote this down. ‘And now I would like to speak to Charlotte and see the schoolroom.’

Mrs Venn consulted her watch. ‘There is a lesson about to conclude in a few minutes. Let us go down.’

Frances learned that there were two schoolrooms, both on the ground floor. They did not connect and each had a separate entrance from the hallway. At the far end of the house another door gave access to stairs, which led to the basement kitchen and a room where meals were taken.

Mrs Venn first showed Frances the front room, which was currently unoccupied. Because of its size and the generous natural light, it was used for music, dance, deportment and art. There was a small pianoforte in one corner and a cupboard for paints and brushes. The walls were tastefully decorated with examples of the girls’ work, which showed that the most recent subject studied was a vase of flowers, and there was also a pretty display of painted fans and posies of dried flowers embellished with ribbon. Frances inspected the room and made polite compliments, until the movement of feet next door told her that the French lesson with Mlle Girard had ended. They passed into the hallway, where the teacher, a dainty little woman of about twenty-five, was ushering the girls from the room. The pupils, who appeared to range in age from twelve to seventeen, were clad in plain grey dresses and spotless white pinafores, each girl’s hair shining as if brushed only moments ago, and tied with a grey bow. Mrs Venn spoke briefly to Mlle Girard, who cast her dark eyes and an arched eyebrow at Frances. She then spoke to one of the girls before departing with her youthful train following, leaving Charlotte Fiske, who was already starting to look afraid, in the custody of Mrs Venn.

‘Come with me, Charlotte,’ said Mrs Venn, in a far kinder tone than she had reserved for Frances. ‘This is Miss Doughty, who would like to ask you some questions.’

Charlotte was fourteen but looked younger. She re-entered the schoolroom timidly, and Frances realised that with her awkward height, she must tower over the girl. She wondered what Charlotte was most afraid of – being blamed herself, or causing another’s disgrace.

The schoolroom was comfortably large enough for a class of twelve. There were individual wooden desks with lids, arranged in three rows of four, a higher desk and chair for the teacher, and a large cupboard for stationery. A blackboard rested on an easel and had already been thoroughly scoured. A chart on the wall listed which girls were responsible for such tasks as cleaning the board after each lesson, the supply of ink, and ensuring that the room was tidy before being vacated. There were maps on display, some framed embroidery samplers, and a portrait of the Queen. Frances would have preferred to speak to Charlotte alone, but Mrs Venn at once went to the instructor’s chair, sat down, took up a pen and looked immovable.

‘Charlotte,’ said Frances gently, ‘Your father has asked me to find out who put the pamphlets in the desks. I know it was very upsetting for everyone, so when I know who that person is I would like to speak to them and ask them not to do it again.’

Charlotte’s lower lip trembled. ‘I don’t know who did it – really I don’t!’

‘And I believe you,’ Frances reassured her. ‘But I am hoping you may be able to help me. I know that you are a clever girl and your Papa and Mama are very proud of you.’ Charlotte looked less afraid and managed a little smile. ‘So – would you like to show me where you found the pamphlet?’

Charlotte went to a desk on the far side of the room and opened the lid. Inside Frances saw a pencil case and a pile of exercise books with covers of different colours denoting the subject within – green for botany, blue for French, pink for arithmetic and so on. Charlotte’s name, written with a studied effort at neatness, was on every book. The French book was on top of the pile and Frances picked it up, to see immediately underneath it a primer of French phrases and a book of nouns and verbs. ‘So when you have just completed a lesson, the books for that lesson are generally to be found on top,’ said Frances. ‘Can you show me which book the pamphlet was in?’

Charlotte quickly rifled through the desk and found her arithmetic primer, a volume of about a hundred pages and some smaller booklets of about eight pages each, which were sets of exercises. ‘It was in here,’ said Charlotte, holding out a booklet devoted to the subject of long division.

Frances took the booklet. ‘Whereabouts in your desk was this yesterday morning?’ she asked.

‘It was inside my arithmetic book. That was underneath most of the others.’

‘And when did you last look at these exercises?’

‘At the lesson the day before.’

‘You are sure that the pamphlet was not there then?’

‘Oh yes, quite sure,’ said Charlotte. At that moment the doorbell sounded.

Frances turned to the headmistress. ‘Mrs Venn, I believe you conducted the search of the other desks?’

‘Together with Miss Baverstock, yes,’ said Mrs Venn, somewhat taken aback to be made the object of questioning in front of one of her pupils.

‘I suppose that no note was made of exactly where each pamphlet was found?’

The headmistress set her mouth in a firm line of displeasure.

‘I am sure that at the time no such need was anticipated,’ said Frances.

‘You are correct. All I can tell you is that they were in locations similar to that Charlotte has described.’

‘Tucked well away so that someone making a routine inspection of the desks would not have seen them,’ said Frances.

‘Exactly so.’

There was a knock on the door and the maidservant entered.

‘Yes Matilda, what is it?’ asked Mrs Venn.

‘It’s Mr Rawsthorne to see you Ma’am.’

Frances wondered why the prominent Bayswater solicitor had come calling. He was also her own family’s solicitor and a friend to her father, who had given them much sympathetic assistance during the recent distressing time. She knew that he had two young daughters and thought it possible that they were pupils at the school.

‘He says it’s very important,’ added Matilda.

From her expression, the headmistress was clearly unhappy about leaving the room. She glanced at her watch and sighed. ‘Very well, show him up to my study.’ She rose and handed Frances a sheet of paper, on which she had been writing during the interview the list Frances had required of staff, pupils and servants. ‘Charlotte – the next lesson is deportment and will take place in one minute. Do not be late!’

As soon as Mrs Venn had departed, Frances managed to fold her tall frame into one of the girls’ chairs, so that she was more on a level with Charlotte.’ Just one or two more questions,’ she said. ‘When you found the pamphlet, you began to read it, didn’t you, because of course you were curious to know what it was.’

Charlotte began to look afraid again. ‘Yes, but – I don’t remember anything!’

‘I am sure,’ said Frances, soothingly, ‘that your Papa and Mama are very pleased to know that you recall nothing of what was in the pamphlet, and Mrs Venn shares that view. I, on the other hand, am very sorry to hear it, as it would help me a great deal.’

Charlotte frowned and contemplated her feet.

‘Perhaps if you could try to remember just a little. I am told that the title was “Why Marry?” Is that correct?’

‘Yes, I think so,’ said Charlotte grudgingly. ‘I didn’t really understand what it meant.’

‘And had the author been courageous enough to put his or her name to it?’

‘No. There was no name, only – A Friend to Women.’

‘I see,’ said Frances, smiling encouragement, ‘how very interesting! I wonder what that charitable person had to say? I would be most entertained to find out!’

The girl’s lips moved but no sound emerged.

Frances leaned forward and spoke in a confidential tone. ‘You have my promise that I will say nothing of what you tell me.’

Charlotte glanced quickly over her shoulder at the door, then took a deep breath. ‘It said – that before a woman marries she should discover all of the man’s character – but that many women, on finding it out, would choose not to marry at all. But I don’t know what that means and I didn’t read any more!’

Frances felt quite sure that Charlotte had read more, but was also certain that this was all she would tell.

When Charlotte had scurried away to her lesson, Frances made some notes and considered what she had learned. For a person to enter the schoolroom and distribute the pamphlets by simply placing one in each desk was a task that could be accomplished in less than a minute. To extract a booklet, put the pamphlet inside and then conceal it between the pages of a book and then tuck it securely away, and do this twelve times, was altogether a lengthier operation. The culprit must have had the leisure to do it, with reason to feel confident that he or she would not be interrupted, and might also have been someone who would have been able to explain away their presence should another person unexpectedly appear. Frances looked at the timetable. After the Tuesday arithmetic lesson ended at twelve the class had been split into two, the older girls remaining in the schoolroom for history with Mrs Venn and the younger transferring to the front room for music with Miss Baverstock. Following this there was an hour when the girls and staff all took luncheon together. In the afternoon there had been four lessons, but at no time had the schoolroom been unused. Lessons ended at five o’clock, when the pupils who did not board had been collected and those who did had afternoon prayers then made their ablutions, had supper, and went to bed. The obvious time to put the pamphlets in the desks was between five, when classes ended for the day, and nine the following morning.

The list provided by Mrs Venn showed that only three pupils boarded, the daughters – aged twelve, thirteen and fifteen – of a gentleman called Younge. The only servant who boarded was the housemaid, Matilda, and of the teaching staff, only Mrs Venn, Miss Baverstock and Miss Bell. Mlle Girard and Mr Copley (botany, painting and drawing) resided elsewhere.

She was deep in thought when Mrs Venn returned. ‘I would like to view the rest of the premises and see where those who reside here are accommodated,’ said Frances.

‘Of course,’ said Mrs Venn with glacial politeness.

Mrs Venn, Frances found, slept in a small but comfortably appointed room that adjoined her study, which also served as a washroom and dressing room. On the same floor was a bedroom for the accommodation of Miss Baverstock and Miss Bell, a water closet, a wash room, and a common room where the girls did needlework and informal study and had tea. On the second floor was a girls’ dormitory, a storeroom, and a small room for Matilda. The basement was divided into two, a kitchen and a room where meals were taken. There were twelve places set at a long table for the pupils and a smaller table for the teaching staff. The servants, after bringing in the meals, ate in the kitchen. Frances thought it very possible that one of them might have been able to slip away to the schoolroom for a few minutes without arousing suspicion.

Matilda and Mrs Robson were working in the kitchen, the former stirring a pot of soup and the latter, with heavily floured arms, putting the finishing touches to a large, thick-crusted pie of savoury aspect. Mrs Robson stopped what she was doing as the headmistress and Frances entered, and stood respectfully by the table, but Matilda simply looked around briefly and went on stirring.

‘I trust that that is all you need to see?’ enquired Mrs Venn.

‘It is,’ said Frances, sitting down. ‘And after such hard work I would welcome a cup of tea.’

Mrs Venn paused a little longer than was necessary. ‘Matilda,’ she said at last, ‘please provide Miss Doughty with a cup of tea before she departs.’ Without a word, Matilda put her spoon down and went to fetch the teapot.

Frances glanced at the timetable. ‘I will return after two o’clock to speak to Mr Copley, Mlle Girard, Miss Baverstock and Miss Bell. I would be grateful if a private room could be provided. At five I would like to see the three girls who board here.’

‘Of course,’ said Mrs Venn, with an effort at being accommodating, ‘I will make the arrangements.’

‘This is all about those silly papers in the girls’ desks, isn’t it?’ said Mrs Robson, when Mrs Venn had left. ‘I hope you don’t think we had anything to do with it?’

‘Not at all,’ said Frances. ‘But you may be able to help me by letting me know what visitors came to the house between twelve on Tuesday and nine the next morning?’

‘Mr Sandcourt came on the Tuesday,’ said Matilda, bustling with the teapot, which Frances saw was being filled for more than one, ‘and then Mr Fiske with Mr Miggs.’

‘And they all had appointments?’

‘They did, and I took them straight up to see Mrs Venn, and showed them out when they went.’

‘No one else was here? No one who might have waited in the hallway?’

Matilda shook her head. Mrs Robson put the pie in the oven and opened a box of currant biscuits and they all sat down to tea.

‘Were there any visitors on the Wednesday morning?’ asked Frances.

‘Not at the front door, no,’ said Matilda.

‘There were the usual delivery men at the kitchen door, and Mrs Armstrong, who collects the linens to go to the washhouse,’ said Mrs Robson, ‘but none of them even came inside let alone went upstairs.’

‘And Davey came to see me,’ said Matilda with a superior smile. ‘My intended. I gave him a cup of tea.’

‘Mrs Venn has no objection to your young man calling here?’ asked Frances with some surprise.

‘None at all,’ said Matilda, firmly.

‘Can you think of anyone who might have had the opportunity to put something in the girls’ desks – or who might have wanted to do such a thing?’

Both the servants shook their heads. ‘I can’t see what all the fuss is about,’ said Mrs Robson.

‘What was in the papers?’ asked Matilda, with a sly little laugh and a mischievous twinkle in her eyes. ‘It wasn’t one of those romance stories with pirates and brigands? Can I see one?’

‘They were not stories at all, so I understand,’ said Frances, ‘but they have been burnt so I have not been able to examine one.’ Matilda looked disappointed.

‘Well,’ said Mrs Robson, ‘If Mrs Venn has burnt them then it must be for the best.’ She gave a firm nod, gulped the rest of her tea and went back to work.

There was no more to be discovered so Frances finished her tea and departed. Thus far, she reflected as she walked home, her enquiries had resulted in the conclusion that those people who had the opportunity to put the pamphlets in the desks were the very ones who had no motive to do so. She was left with two very important questions. At some point in the future she would firstly have to ask Mrs Venn for the real reason she had destroyed the pamphlets, and, secondly, what it was that she was afraid of, but that time had not yet come.

CHAPTER THREE

Frances returned to her almost desolate rooms in Westbourne Grove and ate a simple dish of boiled eggs, then Sarah conjured a wonderful pudding from old bread, apples and sugar. She had not yet succeeded in finding a suitable apartment, and Frances gathered from Sarah that the cost of respectable lodgings for two was greater than she had supposed and more than Frances could reasonably spare from her carefully hoarded resources. Nevertheless, when the meal was done, Sarah voyaged forth again with a tangible air of optimism, leaving Frances to study the notes of her interviews. Alone, with her few possessions packed in boxes around her, Frances contemplated her future, and hoped that she had not given Sarah false hopes of success. One commission was all very well, but she had not given any thought as to how she was to find another. She wondered about the cost of putting an advertisement in the Bayswater Chronicle. ‘Lady detective. Discretion assured.’ If nothing else that would attract the ladies in Bayswater who had bad husbands, and Frances felt confident that there would be many of those.

For the present her thoughts revolved around the possible motives for the placement of the pamphlets in the school. Mr Fiske had already told her of Mrs Venn’s impeccable history, but she wondered if there was something to be learned from the circumstances of the three governors – not what they proudly showed to the world, but those matters on which they preferred to remain silent.

When Sarah returned she brought with her two unexpected visitors. Charles Knight and Sebastian Taylor. ‘Chas’ and ‘Barstie’, as they were familiarly known, were two businessmen, as inseparable as brothers, who had befriended Frances very recently. She had wisely decided quite early in the acquaintance not to ask them the nature of their business. While their fortunes ebbed and flowed, sometimes with startling suddenness, the one thing that remained constant was their abject fear of an individual who they knew only as ‘The Filleter’. Frances had only encountered him once, a black-clad, repellently odorous and greasy young man with a thin sharp knife at his hip. The mere mention of his name was enough to put them to flight.

When Frances had last seen them, they were smartly dressed, but leaving Bayswater as fast as their legs could carry them. Today, while glad of their company, she was sorry to see that they were clad in garments which, while once worn proudly by gentlemen of fashion, would nowadays be rejected by all but the most desperate pawnbroker.

Frances greeted them warmly, and, noticing a jaded look which they were polite enough to try and conceal, sent Sarah to bring them tea, bread and potted meat, which they consumed with considerable relish.

‘I will be taking new apartments soon,’ declared Frances. ‘When I am settled, I would be very pleased for you to call. I hope that you intend to remain in Bayswater?’

‘We are even now in search of suitable accommodation in this immediate area,’ replied Barstie, waving a languid hand as if all the amenities of the district were laid out for his choosing. ‘Bayswater is quite the pinnacle of gentility for those of us who prefer to live useful lives.’

‘We have the strongest possible reasons to be drawn to its opportunities, its multitudes and its delights,’ said Chas. The tea and food had restored his strength and his rounded face glowed pink with energy. ‘My friend has an ardent romantic nature and wishes to lay his heart at the feet of a young lady with considerable financial expectations. The young lady, sadly, is immune to his protestations – in short, she will not have him. But he will not abandon his quest.’

‘Now don’t pretend that your heart is unengaged,’ said Barstie. ‘Bayswater also holds the key to your happiness.’

‘Happiness is a full purse, and something in the bank,’ said Chas. ‘All my business is here, and no man, not even a certain person whose name I will not mention for fear of soiling my lips, will keep me from it. I mean to make my fortune, Miss Doughty, and then I hope to be worthy of a young lady of exceptional qualities. A young lady who knows the value of things – who I can entrust with my heart, my life, even my books of account.’

‘She must be very remarkable,’ said Frances, who had once received an unsubtle hint that the business acumen she had gained during the years working in her father’s shop had stirred Mr Knight’s tender interest.

‘Oh, she is, she is. But I have not spoken one word of devotion – nor will I until my fortune is secure!’ He nodded very significantly.

‘Well, gentlemen, if you have not yet found suitable accommodation – I hesitate to mention it as it is hardly more than bare rooms —,’ she saw their faces brighten and pressed on. ‘Although I am leaving very soon, I do have the use of this property for two or three more days before Mr Jacobs brings his effects. You are very welcome to stay until then. There are two quite unoccupied rooms above.’

‘That is very kind of you,’ said Barstie, casually. ‘I think, Chas, we may consider availing ourselves of the offer.’

Chas frowned. ‘Er – as to the question of rent —’

‘Oh please don’t think of it,’ said Frances. She pretended not to notice their palpable relief.

‘Such generosity!’ said Chas, beaming. ‘We accept at once!’

Frances decided not to raise the question of their luggage, which might cause them embarrassment as she was fairly certain there was none. ‘There is, however, one little service you might perform for me,’ she went on. ‘I need information about three gentlemen who reside in Bayswater. Their business and family circumstances.’

Chas and Barstie exchanged worried glances. ‘This is not another case of murder, Miss Doughty?’ asked Barstie anxiously.

‘Oh, no,’ she reassured him, ‘nothing so terrible as that. I would like to know if these gentlemen might have rivals – or enemies, even. Whether justified or not. Even the most respectable of men may make enemies who envy them their success.’

Chas and Barstie both nodded sagely as if they had whole armies of envious rivals. ‘Let us know their names and we will find out everything we can,’ said Chas.

‘They are Mr Algernon Fiske, who is an author I believe, Mr Roderick Matthews, a market gardener, and Mr Bartholomew Paskall, property agent.’

‘They are known to us by repute only, though not personally,’ said Chas.

‘I would also like to know something of the circumstances of Mr Julius Sandcourt, who is married to Mr Matthews’ eldest daughter, and an associate of Mr Fiske’s called Miggs,’ Frances added. ‘I will meet any expenses of your enquiries of course.’ She paused. ‘In advance – why not?’ She found a few shillings in her purse and handed them over. ‘Now, gentlemen, I have an appointment very shortly, but if you were to join me for supper at seven, I would be delighted.’

The arrangements completed, Frances returned to Chepstow Place, where Matilda admitted her to the school and asked with a smirk if she had solved the puzzle yet.

‘Not yet,’ said Frances, ‘unless there is something you can tell me.’

‘Oh I’ve said all I know, which isn’t anything,’ said Matilda. ‘Mr Copley’s waiting for you. Now I’d be very surprised if he didn’t know something.’

Frances was ushered into the art room, where she found Mr Copley carefully arranging chairs in the largest circle the room would permit. In the centre of the circle was a small table on which sat a cut-glass vase, which held a fresh posy of spring flowers. Copley, a small sprucely dressed man of about thirty with a prematurely receding hairline, looked up with a smile as Frances entered the room.

‘Ah, Miss Doughty, how may I assist you?’ he enquired brightly, flapping his hand at Matilda by way of dismissal. She turned and flounced back to the kitchen.

‘I was hoping you would be so good as to answer some questions,’ said Frances.

‘Of course! Of course! And you may assist me, Miss Doughty,’ he said, placing a chair beside the little table, ‘by seating yourself here.’

Frances sat and took out her notebook while Mr Copley bustled about, checking the view of the table from each of the seats in the circle. ‘I understand that you do not lodge in the school,’ Frances asked.

‘Oh dear me, no, that would be quite improper. I have my own rooms in the Grove. Some might call my humble abode an attic, but to me, Miss Doughty, it is a place near to heaven. There I have a little studio where the light illuminates my work and I may grow my garden of precious flowers near the window. If I might impose on you, Miss Doughty, could you lean a little more to the left? Just so!’

Frances, trying to accommodate him while also writing in her notebook, said, ‘And what classes do you teach here?’

‘Botany twice a week, drawing twice and painting twice. All at 3 p.m. There is a school in Kensington where I have classes every morning. I also have other employment illustrating books, and in my leisure moments I am inspired by my own notions of Art. Perhaps if you might place your left hand on the table?’ He rotated the vase about an inch, stepped back to gaze at it, and sighed. ‘The most beautiful thing in the world to me is the flower. The delicate fragile petals, as they just begin to open, the hint of dewy moisture within. So innocent! So pure! How it lifts my spirits to see it.’

Frances took a moment from her new occupation as artist’s model to make a note. ‘Please could you tell me exactly where you were between midday on Tuesday the second of March and nine the following morning?’

He gazed at her. ‘You are very young, Miss Doughty.’

‘I am nineteen,’ she said. ‘And I would be obliged if you would answer my question.’