Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

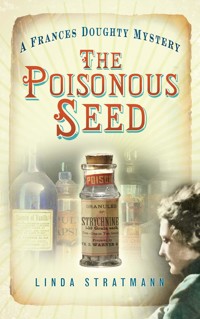

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Frances Doughty Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

When a customer of William Doughty's chemist shop dies of strychnine poisoning after drinking medicine he dispensed, William is blamed, and the family faces ruin. William's daughter, nineteen year old Frances, determines to redeem her ailing father's reputation and save the business. She soon becomes convinced that the death was murder, but unable to convince the police, she turns detective. Armed only with her wits, courage and determination, and aided by some unconventional new friends, Frances uncovers a startling deception and solves a ten year old murder. There will be more deaths, and a secret in her own family will be revealed before the killer is unmasked, and Frances will find that her life has changed forever. The first book in the popular Frances Doughty Mystery series.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 577

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the two people who inspired ‘Chas’ and ‘Barstie’ with appreciation and affection, and my thanks for taking it in such good part!

CONTENTS

Title page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Author’s Note

About The Author

Also By The Author

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

Police Constable Wilfred Brown strode briskly along Westbourne Grove, his boots thudding heavily on the wooden paving. A few days before, dirty yellow fog had swirled thickly across London, turning daytime into twilight, burning eyes and lungs, and dissuading all but the most determined or the most desperate to venture out of doors. The return of daylight had brought the Grove back to life again, but it was still bitterly cold, and he carefully warmed his fingers on the top of the bullseye lantern that hung from his belt. Last month’s Christmas bazaars had become this month’s winter sales, and the Grove was choked with carriages, a lone mounted policeman doing his best to make the more persistent loiterers move on. The constable wove a determined way through armies of large women in heavy winter coats fiercely clutching brown paper parcels, vendors of hot potatoes and mechanical mice, and deferential shop walkers braving the cold to assist cherished customers to their broughams. The chill air was seasoned with the scent of damp horses and impatient people. Despite the appearance of bustle and prosperity, there were, however, signs that all was not well in the Grove. The bright red ‘Sale’ posters had a sense of desperation about them, and here and there were the darkened premises of businesses recently closed. On the north side of the Grove, the unfashionable side, opposite the sumptuous glitter of Whiteleys, Wilfred found his destination, the murky yellow glow of the morning gas lamps softening the gilded lettering of William Doughty & Son, Chemists and Druggists. He pushed open the door and the sharp tone of an overhead bell announced his entry into the sweet and bitter air of the shop, where the glimmer of gaslight polished the mahogany display cases, and within their gloomy interiors touched the curves of porcelain ointment pots, and highlighted the steely shine of medical instruments.

It was a small, narrow shop, in which every inch of space was carefully utilised. There were cabinets along its length, filled with neat rows of bottles and jars, and, above them, shelves reaching almost to the ceiling arrayed with more bottles, lined up like troops on parade. In front of the counter there was a single chair for the benefit of lady customers, and an iron stove filled with glowing coals, gamely supplying a comforting thread of warmth. Behind the counter were deep shelves of brown earthenware jars, and fat round bottles with glass stoppers, some transparent, some opaque blue or fluted green, each labelled with its contents in Latin. Below were dark rows of wooden drawers with their own equally mysterious inscriptions. Nowhere, he observed, was there any speck of dust.

Wilfred paused as a tall young woman in a plain black dress and a white apron finished serving a customer; a delicate-looking lady who shied away at the sight of his uniform and left the shop as quickly as she could.

He stepped forward. ‘Good morning, Miss. May I see the proprietor?’

The young woman looked at him composedly, lacing her long fingers in front of her, a subtle glance noting the striped band on his left cuff that showed he was on duty.

‘My father is unwell and resting in bed,’ she said, her tone implying, in the nicest possible way, that that was the end of any conversation on that subject.

Wilfred, who stood five feet nine in his socks, was unused to meeting women tall enough to look him directly in the eye and found this rather disconcerting. Recalling that the business was that of Doughty & Son, he went on: ‘Then may I see your brother?’ He could have kicked himself as soon as the words were out.

Miss Doughty could not have been more than nineteen. She was not pretty and she knew she was not. The face was too angular, the form too thin, the shoulders too sharp. She was neat and capable, and her hair was drawn into a careful knot, threaded with a narrow piece of black ribbon. Her one article of adornment was a mourning brooch.

Her eyes betrayed for a brief moment a pain renewed. ‘My brother is recently deceased.’ She paused. ‘If you require to see a gentleman, there is a male assistant who is on an errand but will, I am sure, return shortly. If not, then I should mention that I have worked for my father for several years.’

Wilfred, who could already see in her the makings of the kind of formidable matron who at forty years of age would be enough to terrify any man, took a deep breath and launched into his prepared speech.

‘You may have heard that Mr Percival Garton of Porchester Terrace died last night?’

‘I have,’ she replied. Bayswater was a hive of talk on all subjects, and several customers had arrived that morning eager to tell the tale, each version more dramatically embellished than the last.

Frances Doughty had never met the Gartons but they had been pointed out to her as persons of eminence. They were often, in good weather, to be seen taking the air, an anxious nursemaid following on with the children, of whom there were now five. Percival was something over medium height, with handsome features impressively bewhiskered, his figure inclining to stoutness, while Henrietta, with a prettily plump face, was ample both of bosom and waist. Frances had observed the way that Henrietta placed her hand on her husband’s arm, the little glances of confidence that passed between them, the small acts of consideration that showed that, in each other’s eyes at least, they were still the same graceful and slender creatures they had been on the day of their wedding. There was a delightful informality about Henrietta’s pleasure in her husband’s company, while Percival, at a period in life when so many men were pressed down by the cares of business and family, showed the world a smooth and untroubled brow. Bayswater society had judged them a most fortunate couple.

‘Is it known how he died?’ asked Frances.

‘Not yet, I’m afraid. We are making enquiries about everything he ate and drank yesterday, and it is believed that he had a prescription made up at this shop.’

‘I’ll see.’ She moved behind the wooden screen that separated the dispensing desk from the eyes of customers, and emerged with a leather-bound book which she placed on the counter. As she turned to the most recent pages,Wilfred saw that it was a record of prescriptions.

‘Yes, here it is.’ She pointed to some faint and wavering script that he felt sure was not hers. ‘Yesterday evening – a digestive mixture.’

‘I’m not sure I can read that, Miss,’ said Wilfred, awkwardly. ‘Is it in Latin?’

‘It is. I’ll show you what it means.’ She fetched two round bottles from the shelf behind her, one clear and one pale blue, and placed them on the counter, then added a flat glass medicine bottle and a conical measure. ‘First of all, two drachms – that is teaspoonfuls – from this bottle, tincture of nux vomica.’ She pointed to the clear bottle which was half full of a brown liquid. ‘The tincture is a dilute preparation from liquid extract of nux vomica which in turn is manufactured from the powdered seed. Two drachms’ – her long finger pointed out the level on the measure – ‘are poured into a medicine bottle this size. We then add elixir of oranges’ – she indicated the pale blue bottle, which was only a quarter full – ‘to make up the total to six ounces. The elixir is our own blend, syrup of oranges with cardamom and cassia. Many people take it alone as a pleasant stomachic. The whole is then shaken till mixed. The dose is one or two teaspoonfuls as required.’

‘This nux vomica …’, he left the question unsaid but she guessed his meaning.

‘The active principle is strychnia, commonly known as strychnine.’ She saw his eyebrows climb suddenly and smiled. ‘In very small amounts.’

Wilfred frowned. ‘What if he took more than the proper dose?’

‘I can assure you,’ said Frances firmly, ‘the amount of strychnia in this preparation is so small that Mr Garton could have swallowed the whole six ounces of his mixture and come to no harm. Also,’ she turned through the pages of the book, ‘It is known that Mr Garton does not have an idiosyncrasy for any of the ingredients, as he has had the mixture several times before without ill-effect.’ She pointed out the entry for a previous prescription, this one in a neat legible script. ‘And this is not freshly made-up stock. As you can see from the levels in the bottles, we have dispensed from this batch many times in the last few weeks.’

Wilfred nodded thoughtfully. ‘Are you – er – learning to be a chemist, Miss? I’ve heard there are lady chemists now.’

She paused, and Wilfred, to his regret, saw once again a sadness clouding her eyes. ‘One day, perhaps.’ It was not the time to explain. Frances recalled the long evenings she had spent in diligent study to prepare for the examination that would have admitted her to the lecture courses of the Pharmaceutical Society, and the incident that had put a stop to her ambitions; her brother Frederick’s fall from an omnibus and the injury which had sent poisons coursing through his blood. There had been two years during which she had nursed him, two years of fevers and chills and growing debility, three operations to drain the pus – procedures which would have killed an older man – the inevitable wasting of strength, and decline into death at the age of twenty-four. It was a time during which her grieving father had dwindled from a hale man of fifty to a shattered ancient, becoming a second invalid requiring Frances’ constant care.

‘Can you advise me how much of the mixture remains in the bottle?’ asked Frances. ‘I really do doubt that he drank it all.’

‘We do have a slight difficulty there,’ admitted Wilfred. ‘The maidservant was so upset she dropped the bottle and most of the medicine spilled out. We are hoping that what is left is enough for the public analyst but we have no way of knowing how much he took.’

‘I see,’ said Frances. ‘All the same, I believe you may safely rule out Mr Garton’s prescription as being of any significance in his death. When is the inquest?’

‘It opens at ten tomorrow morning, at Providence Hall, but I doubt they’ll do more than take evidence of identification and then adjourn for the medical reports. If you’ll take my advice though, I suggest you ask your solicitor to watch the case. You never know what might be said.’

There was a sudden loud jangling of the bell and a dapper young man with over-large moustaches burst into the shop, his eyes wide with alarm. ‘Miss Doughty, I met a fellow in the street and he told me —’. He halted abruptly on seeing Wilfred and gasped, ‘Oh my Lord!’

‘Constable, this is Mr Herbert Munson, my father’s apprentice,’ said Frances evenly. ‘Mr Munson, I would beg you to be calm. The constable is merely enquiring about the prescription made for Mr Garton yesterday.’

Breathlessly, Herbert dashed to the counter and glanced at the book. ‘Yes, of course. I remember it very well, I was here at the time, and I can assure you that everything was in order.’ He threw off his greatcoat. ‘I’ll make up some samples of the stock items for you to take away. The sooner this is settled and we are cleared of suspicion the better.’ He busied himself behind the counter. Despite the chill weather he was sweating slightly, and had to make an effort to steady his hands as he poured the liquids. Frances remained calmly impassive as she helped to seal and package the bottles.

‘We would appreciate it, Constable,’ said Frances, handing Wilfred the parcels and looking him firmly in the eye, ‘if you could let us know the outcome of your enquiries.’

‘Of course, Miss Doughty.’

‘And should I wish to speak to you again, where can I find you?’ Frances had already observed his collar number, and now produced a notebook and pencil from her apron pocket and solemnly wrote it down.

‘You’ll find me at Paddington Green station at either six in the morning or six at night. Just ask for Constable Brown.’ He smiled. ‘Good day to you, and to you Sir.’ As Wilfred trudged away his thoughts turned, as they so often did during his long hours of duty, to his wife Lily, the sweetness of her face and temper, her diminutive rounded form innocent of any sharpness and angles, more rounded recently since she had borne him their second child (not that he minded that at all), and how she had first melted his heart by the way she had gazed up trustingly into his face.

In the shop, Frances was deftly tidying everything away while Herbert sank weakly into the customers’ chair and dabbed his brow with a handkerchief. At twenty-two he was three years older than she, and had been apprenticed to William Doughty for a year. With the death of William’s son Frederick, Herbert had, without saying a word, assumed that he would in time be the heir to the business, a position which would probably require marriage to Frances. That she held no appeal for him either in form or character hardly mattered, and the fact that she would rather have been doomed to eternal spinsterhood than marry him was something he was unaware of. Slightly built and four inches shorter than Frances, he had deluded himself that his large moustaches made him an object of female admiration, and enhanced them with a pomade of his own mixing. Frances had never liked to tell him that in her opinion he used too much oil of cloves. When he was agitated, as he was now, the pointed tips quivered.

‘They’re saying that Mr Garton was poisoned by your father!’ he gulped. ‘It’s all over Bayswater! They know Mr Doughty has been ill and they’re saying he made a mistake and put poison in the medicine! But I can swear it was all right!’

‘Then that is what the analysis will show,’ said Frances, patiently. ‘You know what Bayswater is like; by tomorrow there will be a new sensation and all this will be forgotten.’

‘We’d best not mention it to Mr Doughty.’ He suddenly sat up straight. ‘In fact, I insist we do not!’

Frances, who was sure she knew better than he what was best for her father, bit back her annoyance. ‘I agree. I hope the matter may be disposed of without him being distressed by questioning.’ She removed her apron. ‘If you don’t mind, Mr Munson, I shall see how he does.’

There was no direct connection between the shop premises and the family apartments above, so it was necessary for Frances to leave the shop by the customers’ entrance and use the doorway immediately adjacent. Ascending by the steep staircase, Frances found the maid, Sarah, in the parlour, wielding a broom with intense application, strewing yesterday’s spent tealeaves to collect the dust. Sarah had been with the Doughtys for ten years, arriving as a dumpy and sullen-looking fifteen year old. With unflagging energy and a fearless attitude to hard work, she had become indispensable. Now grown into a brawny young woman, solid, plain and unusually stern, she showed a quiet loyalty to the Doughtys that nothing could shake, and a tendency to eject by the back door any young man with the near suicidal temerity to court her.

‘Mr Doughty’s still asleep, Miss,’ said Sarah. ‘I’ll bring him his tea and a bit of toast as soon as he calls.’

Frances eased open the door of her father’s room. He was resting peacefully, the deep lines that grief had carved into his face softened by sleep, his grey hair, which despite all Frances’ attentions never looked tidy, straggling on the pillow. For two months after Frederick’s death he had been an invalid, rarely from his bed, and the Pharmaceutical Society had sent along a Mr Ford to supervise the business. Frances had given her father all the care she could, but when he eventually rose from his bed, he was frail and stooped, while his mind was afflicted with a melancholy from which she feared he might never recover. Since the death of her mother, an event Frances did not recall as it had occurred when she was only three, all William Doughty’s hopes for the future had rested on his son, and nothing a daughter could do was of any consolation. Frederick’s clothes were still in the wardrobe, and despite Frances’ pleas, William would not consent to them being given to charity. Often, she found him gazing helplessly at the stored garments and once she had found him clutching the sleeve of a suit to his face, tears falling copiously down his cheeks. Only once before her brother’s death had she seen her father weep. She had been ten years old, and had asked many times to be taken to her mother’s grave to lay some flowers. After many weary refusals he had relented, and on a bleak winter day took her to the cemetery where she saw a small grave marker, hardly big enough to be a headstone, bearing simply the words ‘Rosetta Jane Doughty 1864’. To her horror, her father had fallen to his knees beside the stone and wept. When he had dried his eyes they went home, and she had never mentioned the matter to him again.

It was Frederick who had talked to her about their mother. ‘We had such jokes and merriment!’ he would say, eyes shining. ‘Sometimes we played at being lords and ladies at a grand ball, and danced until we almost fell down, we were laughing so much.’ Then he took his little sister by the hand, and whirled her about the room until William came in to see what all the noise was, and suggested that they would be better employed at their lessons.

In the December that followed Frederick’s death, William had once again assumed his duties in the shop. In truth, he was there only as the nominal qualified pharmacist. His professional knowledge was intact, but his hands were weaker than they had been, with a slight tremor. The work of preparing material for the stock of tinctures and extracts fell largely to Herbert and Frances. In the stockroom at the back of the main shop there was a workbench where the careful grinding, sifting and drying of raw materials was carried out, the mixing and filtering of syrups and assembling the layers of the conical percolator pot. Although William observed the work, he seemed unaware that by unspoken agreement, Herbert and Frances were also watching him. He had confined himself to making simple mixtures from stock and filling chip boxes with already prepared pills. The sprawling writing in the book recording Garton’s prescription had been his. Behind the counter it was usually Frances’ nimble fingers which would wrap and seal the packages so William could hand them to customers with a smile. It was the only moment when he looked like his old self.

Gazing at her sleeping father, Frances noticed, with a tinge of concern, the small ribbed poison bottle by his bedside, which contained an ounce of chloroform. He had taken to easing himself to sleep by sprinkling a few drops on a handkerchief and draping it over his face, declaring, when Frances expressed her anxiety, that if it had benefited the Queen it could scarcely do him any harm.

She closed the door softly and returned to the parlour. ‘Sarah, I don’t know if you have heard about Mr Garton.’

‘I have, Miss,’ she said grimly. ‘I had it off Dr Collin’s maid. I don’t want to upset you, but they’re saying terrible lies about Mr Doughty.’

‘I know,’ said Frances with a sigh.

‘I’ve heard that it’s Mrs Garton herself, who’s accused him. Well I’ve said that the poor lady is so beside herself she doesn’t know what to think.’

Frances sometimes wondered if the servants of Bayswater had their own invisible telegraphy system, since it seemed that once any one of them knew something, so the rest of them instantly knew it too. ‘My father mustn’t be troubled with this,’ she said. ‘He’s too unwell.’

‘I know, Miss, I’ll never say a word.’

Despite what Frances had said to soothe Herbert’s panic, she remained deeply concerned, but there was nothing she could do except write to the family solicitor Mr Rawsthorne asking him to attend the inquest, and hope that the post-mortem examination on Percival Garton would show that he had died from some identifiable disease.

The winter season with its coughs and chills was normally a busy time in a chemist’s shop, but as the day went on it became apparent that the residents of Bayswater were taking their prescriptions elsewhere, while medicines made up the previous day and awaiting collection remained on the shelf. There were some sales of proprietary pills and mixtures, but Frances had the impression that the customers had only come in out of curiosity. Some asked pointedly after the health of William Doughty, and those ladies who were in the shop when he made a brief appearance later in the day, shrank back, made feeble excuses and left. William frowned and commented on the lack of custom, implying by his look that it was somehow the fault of Frances and Herbert. He seemed to be the only person in Bayswater who did not know of his assumed involvement in the death of Mr Garton. Herbert went out in the afternoon for a chemistry lecture, and returned in a state of some distress. A Mrs Bennett, a valued customer of many years, had stopped him in the street and explained at great length and with many blushes that she wanted to take a prescription to the shop and she did so like the way Herbert prepared her medicine and could he promise her that if she brought it in he would do it with his very own hands?

‘I didn’t know what to say!’ whispered Herbert, frantically as he and Frances made up some stock syrups in the back storeroom. ‘She’s one of our best customers and she’s afraid to come into the shop!’ For the sake of the ailing man, Frances and Herbert did their best to behave as if nothing was the matter, and at four o’clock William muttered that they could see to the shop for the rest of the day, and went back upstairs to read his newspaper.

Early the following morning, Constable Brown returned, and this time he was accompanied by a large man with a bulbous nose and coarse face who he introduced as Inspector Sharrock.

‘Is Mr Doughty about?’ said Sharrock, glancing quickly about the shop. ‘We need to speak to him.’

‘He is unwell,’ said Frances. ‘He is in his bedroom, resting.’ Out of the corner of her eye she saw Herbert starting to panic again.

‘Can’t help that,’ said Sharrock, brusquely. He strode up to the counter and thumped it loudly with his fist directly in front of Frances. Herbert jumped and gave a little yelp. Sharrock jutted his chin forward, with an intense stare. It was meant to intimidate, but Frances, standing her ground and clenching her fingers, could feel only disgust. ‘Either he comes down here or we go up to him. You choose.’

The last thing Frances wanted was her father waking up suddenly to find strangers in the house. ‘I’ll fetch him,’ she said, coldly. As she passed Wilfred he gave her a sympathetic look, which she ignored.

It took several minutes to prepare her father for the interview she had hoped to avoid. He was tired and seemed confused, but she explained as best she could about Garton’s death and, amidst protests that he hardly knew how he could help, he agreed to speak to the police. She saw that his clothing was tidy and smoothed his hair, then brought him downstairs. When they entered the shop Sharrock put the ‘Closed’ sign on the door, and ushered William to the seat. ‘Is this your writing, Mr Doughty?’ said Sharrock, thrusting the open prescription book under William’s nose, and tapping the page with a large blunt finger.

‘I expect so,’ said William, fumbling in his pocket for his spectacles, getting them onto his nose at the third attempt and peering at the book. Sharrock pursed his lips and gave a meaningful glance at Wilfred. ‘Yes – that is my writing.’

‘And did you prepare the prescription for Mr Garton?’

‘Well – I – imagine I must have done. Yes – let me see – tinctura nucis vomicae, elixir aurantii – I believe he has been prescribed this before.’

‘The thing is,’ said Sharrock, ‘our enquiries show that the medicine you made for Mr Garton was the only thing he had on the night of his death that was not also consumed by another person. And the doctor who examined the body is prepared to say that the cause of death was poisoning by strychnine. What do you say to that?’

William frowned, and his lips quivered, but he said nothing.

‘Come now, Mr Doughty, an answer if you please!’ Frances, trembling with anger, was about to reprimand the policeman for bullying a sick man, but realised that to plead her father’s condition would only increase the suspicion against him. She came forward and stood beside her father, laying a comforting hand on his arm.

‘Really, Inspector,’ said William at last, ‘I can’t say anything other than that the mixture would not contain enough strychnia to kill anyone.’

Sharrock, towering over the seated man, leaned forward and pushed his face menacingly close. ‘Is it possible, Mr Doughty, that you made a mistake? Could you have put in more of the tincture than you thought? Or could you have put in something else instead? Something a lot stronger?’

‘Inspector, I must protest!’ exclaimed Herbert. ‘I myself was here when the mixture was made up, and it was exactly as prescribed.’ He drew himself to his full height – not a long journey – and as Sharrock stood upright and gazed down at him he quailed for a moment, the tips of his moustaches vibrating, then recovered. ‘I will say so under oath if required!’

Sharrock smiled unpleasantly. ‘And that is what you will have to do, Sir. I must tell you that we are working on the theory that Mr Garton was poisoned due to an error in the making up of his prescription.’

‘I am sure you will find that is untrue,’ said Frances quietly.

Sharrock glanced briefly at her but didn’t trouble himself to reply. Instead he tucked the prescription book firmly under one arm, strode over to the shop door and turned the sign back to ‘Open’.

‘Inspector,’ said Frances, following him before he could depart with the book. She held out her hand for it. ‘If you please.’

He smiled his humourless smile. ‘I’ll hold onto this for the time being. Evidence. We’ll take our leave now. You’ll be hearing from the coroner’s court very shortly. And if you’d like to take my advice, I’d say Mr Doughty looks unwell. He ought to rest.’

As Sharrock departed with Wilfred trailing unhappily after him, Herbert turned to Frances and mouthed ‘What shall we do?’ She shook her head in despair and returned to her father’s side, taking the cool dry hand and feeling it tremble.

‘He was right,’ said William, in a sudden miserable understanding of his condition, ‘I am unwell. I may never be well again. Perhaps I did poison Mr Garton.’

‘No, Sir, I will swear you did not!’ exclaimed Herbert.

‘Come with me, Father,’ urged Frances. ‘You need rest and a little breakfast.’

He sighed, nodded, and went with her. Once he was comfortably settled, with Sarah keeping a careful eye on him, Frances returned to the shop.

‘What did Inspector Sharrock have to say while I was fetching my father?’ she asked.

Herbert shuddered. ‘He wanted to see everything we have which contains strychnia. When I showed him the pot of extract of nux vomica in the storeroom he was very interested indeed. I told him that was where we always kept it, but he didn’t believe me. He tried to imply that we usually kept it on the shelf amongst the shop rounds, and only moved it into the stockroom after Mr Garton’s death to make it look less likely it could have been used in error.’

‘What an unpleasant man,’ said Frances.

‘Miss Doughty, I want you to know that I have the most perfect belief in your father!’ exclaimed Herbert. ‘He is the kindest and cleverest of men!’

‘Thank you Mr Munson. I value your support, and if, as you say, you observed the mixture being made, then that settles any question I might have of an error occurring here. We must wait to hear the public analyst’s report, and hope that it reaches some firm conclusions. The constable informed me that most of the medicine was spilled, which is very troubling. If the inquest was to leave the matter open, it might never be resolved in the public mind.’

‘What if Mrs Garton poisoned him?’ suggested Herbert. ‘Have the police thought of that? Perhaps she put poison in his medicine and then blamed it on your father! Wives do murder their husbands, you know.’

‘Yes,’ said Frances dryly, casting Herbert a pointed look, ‘I am sure they do.’ She paused, thoughtfully. ‘But if the Inspector is determined to find my father at fault then he will not be looking for other explanations of Mr Garton’s death. It is easy for us to form theories, of course, but we know almost nothing of the Gartons, their household and their circle, and only a very little of what happened on the night he died.’

‘That is true,’ admitted Herbert, ‘But there is nothing to be done about that. It’s not as if you can turn detective.’

‘I think,’ said Frances, with a sudden resolve, ‘that is exactly what I may have to do.’

CHAPTER TWO

Having decided to become a detective, Frances soon realised that she had no idea of how to go about it. She was naturally anxious that detective work might lead her into areas inappropriate for both her sex and class, but with the reputation of the business at stake, decided that considerations of propriety might have to be cast aside. She knew that there were private detectives who advertised their services in the newspapers, but recoiled from the idea of entrusting family business to a stranger. Even had she been able to find a reliable, recommended man, her father, parsimonious to a fault, would never have sanctioned the considerable expense involved.

At the breakfast table next morning she sat deep in thought, reviewing all that she knew about Percival Garton, mainly what had been learned from the local gossips, who had flooded into the shop on the previous after noon with rumours eagerly transmitted over their teacups. A wealthy man of independent means, and in his late forties, Garton had lived in Bayswater for more than nine years. Seized with violent convulsions at about midnight on Monday 12th January, he had expired an hour afterwards, in great agony. Garton had been born in Italy where his parents and sisters still resided, but his younger brother Cedric had been visiting Paris and was travelling to London to represent the family at the funeral. Frances took out her notebook and jotted down all the facts she knew. So engrossed was she that she quite forgot to take breakfast. A looming shadow at her side was Sarah, with a disapproving look, and Frances, feeling suddenly shrunk to the size of a nine year old, hastily helped herself to a boiled egg and bread and butter.

Frances then turned to her father’s collection of books, relying principally on the British Pharmacopoeia, Squire’s Companion to the Pharmacopoeia and Taylor’s Manual of Medical Jurisprudence. She did not believe for one moment that her father could confuse the concentrated extract of nux vomica with the more liquid tincture, and the fact that Herbert had observed the making of the mixture put any error of that kind beyond possibility. Despite Inspector Sharrock’s insinuations, the extract had always been kept in the back stockroom, and to use this instead of the tincture would have been a deliberate act, not a moment of inattention to detail. Even if by some incomprehensible mischance, the extract had been used, one or two teaspoonfuls of the resulting mixture would still not have contained a fatal amount of strychnia, but Frances knew too well that people often took additional doses of medicine in the mistaken belief that if a teaspoonful did them good, then four would be four times as beneficial.

The timing of the attack also interested her. The symptoms of poisoning by strychnia could be apparent within minutes of it being taken, but only if it was present in its pure form. When taken as tincture or extract, onset could sometimes be delayed by an hour or two. She would have to wait for the analyst’s report to confirm what, if anything, had been found in the medicine.

Her thoughts led her into darker waters. If the medicine had been correct when it left the shop, then poison might have been introduced into it later. This could scarcely be an accidental act. Self destruction did not appear likely in a man of Garton’s obviously contented demeanour, and even if he had possessed some terrible secret which had led him to take his own life, he would surely have chosen something like Prussic acid rather than endure the long agonies of death by strychnia. Could it be possible that Percival Garton had been murdered? Wealthy men often had enemies, or friends and relatives jealous of their wealth. Supposing Garton had had an enemy who wished to poison him, someone closely enough acquainted with his habits to know that only he drank from the medicine bottle, someone whose presence in his house would not have been remarked upon, and who was therefore able to gain access to the bottle long enough to tamper with it. Frances realised that it was vital she follow the journey of the bottle from its leaving the shop to reaching Garton’s bedside; who handled it, who knew where it was located, where and for how long it might have been left unattended, where and when it was opened; and discover, if possible, how much of the mixture he had taken.

A policeman or a real detective would have had no difficulty in finding the answers to these questions, but Frances knew that she was not in a position even to make enquiries. Still, she felt that by addressing the situation she had made some progress, and decided to start by questioning the one person she felt able to approach – Herbert. She joined him in the shop, and found him gloomily surveying the empty premises. Frances felt suddenly chilled with anxiety. Surely the loyal customers would have returned by now.

‘It was one of the maidservants who brought the prescription,’ said Herbert, in answer to her question. ‘She waited, and took it away with her. I don’t know her name, but it’s always the same one they send.’

Frances nodded. ‘That would be Ada. She’s been with the family for many years, and has always struck me as very sensible. I shall have to speak to her.’ Frances knew Ada to be a simple, honest young woman who had held a touching respect for William Doughty ever since he had provided a remedy for some trifling but painful ailment. She would now prove to be a valuable connection with the Garton household.

Herbert looked astonished. ‘Do you think any person from that house will agree to an interview? It would be highly irregular.’

‘I think Ada would be willing to talk to me, but I don’t know any of the other servants. I have been thinking – there are some important questions that need to be asked, and I was wondering if you would consider approaching them. You could say that you are from the newspapers.’

Herbert gaped at her in undiluted horror. ‘That is quite impossible! I flatter myself that I am well known in this neighbourhood, and I would be recognised at once. Supposing the Pharmaceutical Society was to find out that I had done such a thing? My prospects would be quite gone, and the business damaged beyond repair.’

Frances said nothing, but had to admit that Herbert was right. It was a ridiculous and dangerous idea. Despairingly she realised that the two people whom she would most have liked to interview were, in any case, utterly beyond her reach. It would have been highly improper to approach Mrs Garton, and Dr Collin would tell her no more than she could glean from the newspapers.

After some further thought she composed a note to Ada and sought out Tom, the errand boy, to deliver it. Tom had worked for the Doughtys for three months but in that time had made himself entirely at home. His predecessor in the post had ended a brief and undistinguished career by being arrested for thieving, and Frances had scarcely formed the resolution to find a replacement, when Tom appeared, looking as if he had been born to the job. A small boy in that indeterminate period of life between nine and eleven, he resembled Sarah sufficiently to make it obvious that he was a member of her family, though in what way he was related to her the Doughtys had never liked to enquire. They were aware that Sarah came from a substantial brood, a family whose tendrils spread across most of the East End, and found it convenient to assume that he was a nephew. Tom shared Sarah’s room and made himself generally useful at little cost, since he seemed to be able to feed himself more than adequately by scavenging. Mindful of his need to appear clean and neat in the service of a chemist, Sarah would every so often seize him by his collar, dunk him to his shoulders in a tub of water, and scrub him till his face glowed brightly enough to put Messrs Bryant and May out of business, a process that always elicited some unusual verbal expressions which Frances found both amusing and educational.

Frances found Tom in the stockroom, munching at a piece of bread almost as large as his head, and sent him off to the Gartons’ house in Porchester Terrace with the note.

The next idea to occupy her thoughts was how the medicine bottle might have been tampered with. When the bottle had left the premises it had been sealed with a cork, which had first been mechanically compressed to ensure a secure fit. The bottle had then been wrapped in a sheet of white paper, the original prescription placed in a special envelope which was laid at the side of the bottle, and the whole tied with pink string. The knots of the string had then been sealed with wax, and an impression of William Doughty’s own business seal.

‘How easy do you think it would be for someone to introduce poison into the bottle before it was unwrapped, but without Mr Garton noticing?’ Frances asked Herbert. She felt sure she knew the answer but wanted his opinion to confirm what she was already thinking.

He frowned. ‘I would have thought that anything done in that way would leave some signs. How would they re-tie and re-seal the package? And once the cork was taken out it would be very obvious that the bottle was not as it left the shop.’

‘Could someone have injected poison with a syringe? Then they wouldn’t need to unwrap the bottle.’

There was a pause as Herbert thought about this. ‘That’s the kind of thing one reads about in sensational novels. Not that you read such things, of course. I suppose it is possible for a person of experience, but it would need a very strong needle, and would leave a hole in the paper and the cork.’

Tom returned about half an hour later with a reply in one hand and a corner of piecrust in the other. Frances unfolded the paper, and perused the contents. Ada would be able to speak to her at five o’clock. She decided to say nothing of this to Herbert.

Business remained slow and Frances could easily be spared to attend the opening of the inquest at Paddington coroner’s court, William and Herbert’s attendance not being required on this occasion. Providence Hall was a meeting house on Church Street near Paddington Green. Wearing her winter coat and black bonnet with a demure veil, she travelled there alone, and on foot. It was not a long walk for an active young woman, and Frances had grown too used to her father’s insistence on frugality to even consider taking a cab. The hour that would be required on her return to brush mud and worse debris from her skirts, was of no concern to him. The air was cold, and heavy clouds threatened snow, but the brisk journey warmed her. There was a vestibule outside the main hall where Frances waited to speak to Mr Rawsthorne. Hovering there was a thin gentleman with a sour expression whom she recognised as Mr Marsden, a local solicitor. He was deep in conversation with a handsome, overly mannered man in his early thirties, whose pale hair and tawny skin suggested a life spent in warmer climes, and Frances wondered if this could be Cedric Garton. To her relief, Mr Rawsthorne appeared, and she at once greeted him.

‘My dear young lady!’ exclaimed Rawsthorne, a middle-aged man with kindly eyes who had been her father’s advisor for as long as Frances could remember. He pressed her fingertips sympathetically. ‘And how is Mr Doughty?’

‘Improving daily,’ Frances reassured him.

Rawsthorne spread his hands wide with unfeigned delight. ‘I am so very pleased to hear that! He has given me a great deal of anxiety, and I am vastly relieved at your good news.’

‘Tell me,’ said Frances, ‘the gentleman talking to Mr Marsden, is that Mr Garton’s brother?’

‘I believe that is Cedric Garton.’

Frances cast another look at Cedric, who seemed to be so enamoured of his own profile that he constantly posed to show it off to its best advantage. It suddenly occurred to her that since Cedric Garton did not know her by sight, he was her best and probably only source of reliable information about the personal life of the dead man. She could approach him under a pseudonym and ask questions, and after the inquest he would return to Italy none the wiser. But what pretext could she use? The idea she had suggested to Herbert, that of posing as a newspaper reporter, was, she felt, barred to her. It was most unlikely that she could convince Cedric that she was engaged in such a profession. She was aware that there were lady journalists for she had often heard her father speak of them disparagingly. They were, as far as she knew, mainly concerned with writing articles on literary matters, or subjects in the feminine sphere of life. Frances did not know of any lady who wrote about murder, and, if there was one, suspected that she would not be a girl of nineteen. Had she been a young man, thought Frances, she might have succeeded in such a deception.

‘I regret,’ said Mr Rawsthorne, ‘that very little will be achieved today. The medical reports have yet to be completed, and we cannot expect a verdict until next week. I must tell you, however, that I have heard it is very probable that the doctor will conclude that Mr Garton died of poisoning with strychnine.’

They entered the meeting room where two rows of plain chairs had been placed ready for the jury, a long table and a rather more comfortable chair for the coroner, a decidedly hard-looking chair at one end of the table for witnesses, and, in the body of the hall, rows of seating, such as might be provided for those attending a talk or a concert. Less than half the seats were filled, and Frances thought that several of the men, with well-worn suits and an air of boredom, were from the newspapers.

As Rawsthorne predicted, the proceedings took only a few minutes. Cedric, who revealed that he had no occupation other than travelling and amusing himself, stated that he had last seen Percival a year ago when visiting London, and formally identified the body as that of his brother. The enquiry was adjourned for a week.

The shop was still quiet when she returned. She reported events to Herbert, but he seemed to have something weighing powerfully on his mind, which made it impossible for him to meet her gaze. At last, he spoke.

‘Miss Doughty – I understand your emotions at this time, but I have given matters a great deal of thought and it seems to me that there is a way in which this difficulty may be resolved. I suggest that your father should retire from business. He could take a holiday in some pleasant climate. I’m sure it would do him good. We could easily find a reliable man to supervise the business until I am qualified.’

Frances was silent for a moment, but she could feel a momentary rush of anger which she tried to quell. ‘My father is not an old man, he is simply unwell. You have seen for yourself how much improved he has been in the last weeks. This business is his life, and his daily attendance here is instrumental in restoring him to health. Take him away from it, and he would fret. And have you no consideration for his reputation? Would you have him live out his life under a cloud of suspicion? Surely if he was to retire now, it would be taken as an admission of fault? You yourself have said that there was no fault.’

Herbert said nothing, but there was a point of red on each cheek, which had not been there before.

A new and uncomfortable thought occurred to Frances. It was a difficult subject but she had to have the answer before she could continue. ‘I am afraid I must ask you this, and it may give you offence, for which I apologise. I know your loyalty to the business, and it has occur red to me that your statement to the police that you saw the mixture made, while greatly to our benefit, may not be precisely – true. If not, I will not condemn you, but for my own information, I beg you to tell me the truth now.’

‘I understand why you have asked this question,’ said Herbert, stiffly, ‘and I invite you now, if you have any doubts as to my veracity, to bring me a Holy Bible this very minute, and I will place my hand upon it, and swear to you that I was indeed present when the mixture was made, that I observed it being made, and that it was entirely according to the prescription.’

‘Thank you,’ said Frances, ‘I will not trouble you further on that point.’

For the remainder of the day the atmosphere in the shop was even frostier than that in the street.

At five o’clock, Frances met Ada in the anonymity of early darkness, on the Bayswater Road, where it skirted the edge of the heavily wooded enclave of Kensington Gardens. Their dark garments and obscured faces lent them the air of conspirators. Frances was sorry to make use of the maid’s innocent regard for her father for her own purposes, but feared that it might be only the first such adventure of many.

‘I shouldn’t be talking to you, Miss Doughty,’ said Ada, glancing about her fearfully, as Frances obligingly steered her into the shadows. ‘I can’t stay long. I told them my brother was took ill and I was fetching him some medicine. “Don’t go to Doughty’s then”, they said. Sorry, Miss, but that’s what people are saying.’ She pulled a shawl about her face. Frances suddenly wondered how old Ada was. Under thirty, in all probability, but she seemed tired and her face and hands were rough and red, making her look older, and there was a wheezing in her chest that did not bode well.

‘I don’t want you to get into any trouble, Ada, but it’s all I can think of doing to help my father. The police have questioned him cruelly, and he has been very ill.’

‘He is a kind and generous man,’ said Ada. ‘I’m sure he hasn’t done anything wrong.’

Frances plunged quickly into the questioning. ‘Ada, when you collected the medicine for Mr Garton, who did you hand it to when you returned?’

‘No one, Miss,’ said Ada promptly. ‘I put it on the night table in the bedroom.’

‘Unopened?’

‘Yes.’

‘What time was that?’

Ada frowned. ‘I can’t say exactly – just before seven, I think, maybe ten minutes before.’

So, thought Frances, the bottle had been left unattended for some hours before it was opened. ‘Can you tell me about that night? Did Mr and Mrs Garton dine at home?’

‘No, Miss. They took the carriage and went out at seven. They dined at Mr and Mrs Keane’s in Craven Hill. Mr Keane and Mr Garton are great friends; they often dine at each other’s houses.’

‘I suppose they were getting ready to go out when you returned?’

‘Yes. Master was in his dressing room and Mistress was saying good-night to the children.’

‘Did Mr Garton seem his normal self?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘And were there any visitors to the house while they were out?’

‘No, Miss.’

The available time for Mrs Garton to have tampered with the bottle was hardly sufficient, thought Frances, and the risk of detection surely far too great. ‘When did they return?’

‘It was just after eleven. They looked into the children’s room to see how they were, and retired for the night.’

‘How did Mr Garton seem to you then?’

‘I thought —,’ Ada paused. ‘He looked like he’d dined a bit too well, if you know what I mean. I saw him put his hand to himself, just there.’ Ada indicated her abdomen.

‘Did he say anything about it?’

‘Mistress looked at him in a worried sort of way and he smiled at her and said he was all right, but he thought he had had too much pudding.’ She smiled, sadly. ‘Master liked his pudding.’

‘What happened after that?’

‘I raked out the kitchen fire and laid it ready for the morning, and then I washed and went to my bed. That was just before midnight, and I was asleep soon after. I woke up when all the commotion started. There was Mistress calling out for help, and Master groaning in pain. We were all in an uproar. I ran into the room and saw him —,’ she gave a little gasp at the memory. ‘Oh it was a terrible thing to see – the expression on his face – a smile like Old Nick himself, if you’ll pardon me for saying it and his body all bent back.’

Frances sighed. Ada had described the rictus and convulsions that attended poisoning with strychnia.

‘Do you know what time it was when you were awoken?’

‘Just after midnight, I think.’

‘And where was the bottle of medicine then?’

‘I don’t know Miss, it was all a lot of shouting and confusion and I can’t rightly say.’

‘Who else in the household saw what was happening?’ asked Frances.

‘Well, Mr Edwards – that’s Master’s manservant – he came in and Mistress told him to go and fetch Dr Collin. Then Mary, the nursemaid, looked in, but Mistress sent her to go and make sure the children weren’t disturbed. Then she sent me to get a towel to bathe Master’s face.’

‘What about the other servants? What did they do?’

Ada pulled a wry face. ‘Flora, she’s the kitchen maid, she was so frightened by the screaming, she thought there were burglars in the house, and she put the bedclothes over her head and never came out till morning. Susan, Mistress’s maid, she sleeps though any amount of noise and I had to go and wake her up. Then – Mrs Grange, the cook, and Mr Beale the coachman – they —,’ she hesitated, ‘they didn’t arrive till a bit after everyone else.’

Frances decided to gloss over this irrelevant indecency. ‘I believe you have been with the Gartons for several years.’

‘Nine and a half years, ever since they came to Bayswater.’

‘And the other servants?’

‘Flora has been with us two years but the others, like me, were engaged when Master and Mistress took the house.’

‘Ada, this is very important, did you see what happened to the medicine bottle later on? What about after you came back with the towel?’

Ada shivered, and her lower lip trembled. ‘It was an accident, Miss.’

‘I am sure it was,’ said Frances, gently. She said no more but waited until Ada felt able to go on.

‘When I went in, Mistress had the bottle and was holding it to her nose to smell what was in it. She was crying and saying that Master had been poisoned by his medicine. Then Master went into another fit and she ran to him, and gave me the bottle saying I had to cork it up tight – but I was that alarmed – I dropped it.’

‘Do you know how much medicine was in the bottle then?’

‘No, Miss, I’m sorry.’

‘And what happened to the bottle?’

‘I picked it up and put the cork in and put it back on the nightstand. Later on Mistress gave it to Dr Collin and told him to take it to the police.’

‘Can you guess how much was spilled?’

‘I’m not sure, Miss. When I cleaned it up it was a mark on the carpet about the size of my hand.’

‘I don’t suppose you know when Mr Garton took his medicine or how much he took?’

‘I did hear Mrs Garton tell the doctor that he took it at about a quarter to twelve. I don’t know how much he took, but she said he told her it had a bitter taste and was different from the other bottle he had.’

Frances felt her heart sink. Could her father’s trembling hands have put more than the usual amount of tincture into the mixture? But even if he had, it would still have been far from lethal.

Ada looked around again. ‘I must go, Miss, I’m sorry.’

‘Ada, please, just one more moment, I need to know – did Mr Garton have any enemies? Were there people he argued with, and who might have wanted to do him harm?’

Ada stared at her in astonishment. ‘Oh, no, no one like that! Master was a very kind man with the nicest manners you could imagine. He was very well liked by everyone who met him.’

‘And Mr and Mrs Garton; they were on good terms?’

‘Oh yes, Miss, they were very affectionate. The poor lady is quite distraught. Goodbye, Miss.’

‘Goodbye, Ada, and thank you for speaking to me. If there is anything else you remember —,’ but Ada had disappeared into the darkness.

When Frances returned to the shop, Herbert was busy preparing an ointment, working a greasy yellow mass on a marble slab with a spatula. Presumably, thought Frances wryly, customers were still happy to purchase items for external use. She wanted to talk to Herbert about what she had learned but was reluctant to reveal that she had made an appointment with Ada and instead told him that they had met in the street by accident. She was not used to telling untruths and the words fell from her lips awkwardly, but he seemed not to notice. Perhaps, she consoled herself, it was all part of being a detective, a small sin committed to achieve a far greater good.

‘I don’t believe there was enough time for Mrs Garton, supposing she is our suspect, to have put poison in the medicine without leaving obvious signs of tampering in the time between the bottle being brought in and their going out,’ said Frances. ‘If poison was put in the bottle it must have happened while they were out.’

‘Such a thing is not beyond what an intelligent servant might do, but for what reason?’ observed Herbert.

‘There is another possibility,’ said Frances. ‘Mr Garton might have had something at the house of Mr and Mrs Keane. Not at dinner, which everyone ate, but a drink, perhaps, just before he got into the carriage?’

‘Then he would have suffered an attack on the way home or shortly afterwards.’

‘Not necessarily. If the strychnia is present as nux vomica, sometimes the onset is delayed.’ Herbert frowned thoughtfully, and conceded the point. ‘Now, as we seem to have no customers at present, I shall go to the police station and see what more I can find out from Constable Brown.’ Herbert opened his mouth to protest, but she had already departed.

By the time Frances arrived at Paddington Green Police Station, it was dark and the glow of the tall gas lamp that stood outside was curiously comforting. The building was square and heavy, a four-storey fortress with a deep basement, and a series of pointed crenellations on the roof. As a child she had imagined it to be a castle like those in Frederick’s history books, and wondered if a king lived there. Frances had never entered the station, or imagined she would ever do so, but any concern at encountering the criminal classes of Paddington was necessarily thrust aside. She took a deep breath and ascended the steps to the front door. Inside she found what she assumed to be a waiting area. There was a tall deep counter, manned by a sergeant, with shelves of books and ledgers behind it. In front, there were wooden benches, where a few individuals were seated, some slumped over and dozing, others holding an animated conversation as to which of two persons had struck the other first. Voices dropped as she entered, and she realised that she was the only woman there, and the only person apart from the sergeant with any claim to neatness and cleanliness of dress. Ignoring the stares, Frances marched straight to the counter and asked the sergeant if she might see Constable Brown.

Eyebrows were raised. ‘Not a personal matter, is it?’

‘No, of course not!’ she exclaimed, blushing. Really, what had he taken her for? ‘It is a police matter.’

The sergeant looked dubious, and went through a door at the back, and a few moments later, Wilfred appeared. Without his helmet, the constable looked younger than Frances had at first supposed, no more than twenty-five, with deep chestnut hair and whiskers that needed no pomade. ‘Good evening, Miss Doughty. Inspector Sharrock is out, we can talk in his office.’ He conducted her to a small and dingy room, with a greatly worn desk and chairs, and shelves reaching up to the ceiling stuffed higgledy-piggledy with papers, parcels and boxes of every size and description. Frances saw with some dismay that Sharrock’s desk was piled high with assorted papers in no particular order, and wondered if his mind was in similar disarray.