13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

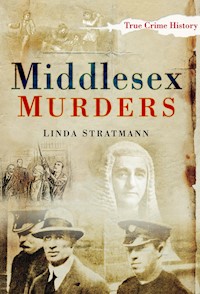

Middlesex Murders brings together numerous murderous tales, some of which were little known outside the county, and others which made national headlines. Contained within the pages of this book are the stories behind some of the most heinous crimes ever committed in Middlesex. They include the murder of John Draper, whose body was found in a well at Enfield Chase in 1816; 15-year-old John Brill, found beaten to death in a wood in 1837 after giving evidence against two poachers; and Claire Paul, killed with an axe at her home in Ruislip in 1938. Linda Stratmann's carefully researched and enthralling text includes much previously unpublished information and will appeal to everyone interested in the shady side of Middlesex's history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Middlesex

MURDERS

LINDA STRATMANN

To John and Janice

First published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Linda Stratmann, 2010, 2012

The right of Linda Stratmann, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8403 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8402 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

1. Murder on the Heath

Hounslow Heath, 1802

2. The Beadle of Enfield

Enfield Chase, 1816

3. Murder in Mad Bess Wood

Ruislip, 1837

4. In the Heat of the Moment

Hillingdon, 1839

5. The Wine Shop Murder

Hendon, 1919

6. Blaming a Woman

Golders Green, 1920

7. The Rubbish Dump Murder

Edgware, 1931

8. The Widow of Twickenham

Twickenham, 1936

9. The Man with a Scar

Ruislip, 1939

10. A Bit of a Fix

Greenford, 1941

Bibliography

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I would like to extend my grateful thanks to everyone who has assisted me with the research for this book. As always, the friendly staff at the British Library, Colindale Newspaper Library and the National Archives have been invaluable, and I was especially delighted to be granted permission to view files in the National Archives which had, until November 2009, been closed. My thanks and good wishes are due to Garry Nathan and everyone at Moorcroft House for the information and a tour of a fascinating estate. I was delighted that a great-niece of Daisy Holt (chapter 6) shared some family memories with me. These personal details are what brings the past back to life and excite me more than any dry document! I would also like to thank the parish officers of St Martin’s Church, Ruislip, and everyone at The Stag, Enfield for their help. My husband’s advice and support as well as his willingness to drive me to the scenes of old crimes and trudge through muddy woods and fields in search of the best pictures is appreciated more than I can say.

All photographs taken by the author are the copyright of Linda Stratmann.

1

MURDER ON THE HEATH

Hounslow Heath, 1802

In 1802 Hounslow Heath was a dangerous place, long known to be the haunt of highwaymen and footpads. This remnant of the ancient forest of Middlesex covered about 25 square miles, and although it was crossed by roads, it was regarded as somewhere to be avoided, or at least passed through as quickly as possible, preferably in a well-guarded coach.

At Feltham, not far from the road which linked Staines and Hounslow, was the country home of 35-year-old John Cole Steele, described as ‘a young man of very amiable character’. The proprietor of the Lavender Water Warehouse, No. 15 Catherine Street, near the Strand, he had married Mary Ann Meyer in 1798. Steele owned a lavender plantation at Bedfont, not far from Feltham, which he visited regularly to give instructions to his manager, Henry Mandy.

On the afternoon of Friday, 5 November 1802, Steele left his London townhouse for Feltham. He was wearing a drab-coloured greatcoat, a shorter coat, breeches with stockings underneath, a striped waistcoat, half boots and a smart round hat. He did not state exactly when he would return, although there was an arrangement that he and his family would gather to celebrate his wife’s birthday on Sunday. When Steele failed to return on Saturday it was assumed that he had been detained by business and was staying overnight at Feltham, and there was no immediate alarm, but when he was not back for the birthday party his family became concerned.

On the Monday morning a messenger was sent to Bedfont and returned with the worrying news that Steele had set out for home on Saturday evening, and, unable to obtain a carriage, had decided to walk across the heath. On Wednesday morning, Steele’s brother-in-law, lavender-distiller Thomas Meyer, went to Feltham to make enquiries. Steele was not at his house, and Henry Mandy confirmed that his employer had left for home at about 7 p.m. on Saturday evening, since when nothing had been heard of him. Steele had not been in the habit of carrying large sums of money and Mandy said that his employer had then had about twenty-six or twenty-seven shillings on him.

Highwaymen rob a stagecoach on Hounslow Heath, c. 1720.

Meyer asked Mandy and another gentleman called Hughes to help him search the heath, going along the Feltham to London road, Meyer and Mandy on the right and Hughes on the left. At a clump of trees near a gravel pit, on the south side of the road, Mandy picked up an old hat cut in pieces, which he handed to Meyer, but it was not the one that Steele had worn, being very much older and resembling a soldier’s hat. The gravel pit was about 10 or 15 yards from the road, and as the men drew near, they saw what they thought was a piece of clothing. Pulling aside the rushes that covered most of the material, Mandy found a drab-coloured greatcoat concealed under the water and pulled it out. He recognised it as the one Steele had been wearing when he last saw him, and noticed that it had a spot of blood on the right shoulder. The three searchers consulted about what to do next and Meyer and Mandy decided to go to the nearby Hounslow cavalry barracks in Beavers Lane and obtain the help of the officers and men to search for Steele. When they returned they found that a great many more people had arrived to join in the search.

It was Hughes who found the body; about 200 yards north of the road, lying in a ditch by a clump of trees, with the turf from the bank pulled across to partly conceal it. Steele lay on his back, the flap of his coat over his face, and a strap around his neck. He was not wearing his hat, stockings or boots. When the body was lifted out Hughes saw that the face was covered in blood and dirt, and there had been a violent blow on the back of the head. The strap had once had a buckle which was broken off, and one end had a knife run through it, and the other end drawn through so it was very tight. About 50 yards away Hughes found a pair of shoes. A large stick was also found. The hat, stick and shoes were handed to Isaac Clayton, the beadle of Hounslow, and they were eventually placed before police magistrate Sir Richard Ford at Bow Street.

The body was conveyed to The Ship public house at Hounslow and a surgeon, Mr Henry Frogley, was called. He found an extensive fracture on the front of the head with lacerations of the skin, and another lacerated injury on the back of the head, both of which he thought had been inflicted with a blunt instrument such as a stick. There had also been a heavy blow on the right arm. The strap was tight enough to cause suffocation, but it was his opinion that the head wounds were the immediate cause of death. The difficult task of telling Mrs Steele of her husband’s death fell to her mother, but initially she was spared the worst details, being told that he had died of a fit. The inquest was held at The Ship and returned a verdict of wilful murder against some person or persons unknown.

Suspicion fell on a man and a woman who had been seen travelling together in Rutlandshire, the man of a very dirty appearance, in a shabby coat but wearing a good quality hat and carrying a stick, the woman in half-boots and stockings which could have been the ones taken from Steele’s body. Letters were sent to justices in Rutland and Leicester, urging that the most strenuous efforts should be made to apprehend the couple, but they were never found. Steele’s family placed an advertisement in a newspaper offering a reward of £50 for information leading to the capture of the murderers. Several known criminals were arrested on suspicion, but after questioning they were released. Four years went by and all hope of finding the guilty persons was gone.

Hounslow Heath.

On 17 September 1806, 26-year-old Benjamin Hanfield (who was then calling himself Endfield) was found guilty at the Old Bailey of stealing a pair of shoes, and was sentenced to transportation for seven years. While in Newgate Prison awaiting transfer to a convict ship, he found himself discussing robberies with the other prisoners, and when the murder of Steele was mentioned he let slip that only three men in England knew the truth of it. The rumour went around the prison that he was involved and was about to betray his associates, and this came to the attention of the authorities.

Hanfield was transferred from Newgate to a prison hulk in Langstone Harbour and shortly afterwards made his first official disclosure regarding Steele’s murder to Sir John Carter, Mayor of Portsmouth. Hanfield said that he had once been a hackney-coachman and had enlisted in the military on at least five occasions, but admitted that he generally made his living by thieving, and had often been tried and convicted at the Old Bailey. According to the Newgate Calendar and a report in The Times, he had been taken dangerously ill and raved about the murder, saying he wanted to tell what he knew before he died. Hanfield’s own account makes no mention of any illness. The official view of Hanfield’s revelations was that he might well know something about the murder of Steele, but he could also have been hoping for a financial reward, or a reduction of his sentence, and it was vital to test the truth of his account, especially as he was incriminating others in his confession.

The interior of Newgate Gaol.

John Vickery, an officer of Worship Street police office, was sent to Portsmouth on 15 November, and brought Hanfield up to town in a coach. On the way the coach passed across Hounslow Heath and as it did so they passed by a clump of trees between the 10 and 11-mile stones, near where Steele had been murdered. Without any prompting, Hanfield pointed out the spot.

At Worship Street Hanfield told the magistrates that the murder had been committed by John Holloway and Owen Haggerty. He had known Holloway for six or seven years and Haggerty for seven or eight and had spent a good deal of time in the company of both, usually in public houses; the Turk’s Head and Black Horse in Dyott Street, and the Black Dog in Belton Street. Holloway had no trade as far as he knew and had worked as a labourer. Haggerty, he thought, had been a bricklayer’s or plasterer’s labourer.

Hanfield was shown the broken hat that had been found on the heath and said it was very like the one Holloway had been wearing on the night of the murder.

According to Hanfield, he had been in the Turk’s Head at the beginning of November 1802 when Holloway had asked ‘if I had any objection to being in a good thing.’ When Hanfield said he was willing Holloway had revealed it was to be a ‘low toby’ or footpad robbery, the details of which he would reveal in a day or two. Two days later, Holloway told him the robbery would be carried out on the following Saturday and they were to meet together with Owen Haggerty at the Black Horse. At that meeting Haggerty confirmed that they would be robbing a gentleman on Hounslow Heath who was known to carry property on him. How they knew this, Hanfield didn’t know, only that Holloway had somehow found it out. Neither did Hanfield say how they knew that Steele would be on the heath that Saturday, since, according to Thomas Mandy, Steele did not have a regular day of the week for going to the plantation. The three walked to Hounslow, with a couple of stops at public houses on the way, the last one being The Bell at Hounslow. They arrived on the Heath at four, then proceeded until they came to the 11-mile stone. Holloway was carrying a large blackthorn stick.

It was almost dark when they reached a clump of trees and there they waited until the moon rose. There was light enough to see a man, who Hanfield later knew to be John Cole Steele, wearing a light-coloured greatcoat and walking alone in the direction of Hounslow. Hanfield accosted Steele, demanding money, and Steele, asking the footpads not to hurt him, gave something to Haggerty. Holloway asked if the victim had delivered his ‘book’ (a pocket-book or wallet used to carry money), but Steele said he did not have a book. Holloway insisted he must have a book, but when Steele again said that he did not Holloway came up behind him and knocked him down with his stick.

Hanfield took hold of the legs of the fallen man, who was begging ‘do not ill-use me’, while Holloway stood over him and Haggerty searched his pockets. The victim began to struggle. He was unexpectedly strong and put up a good resistance, crying out all the time, but just then the men heard the sound of an approaching carriage. Holloway said, ‘I will silence the bugger’ and delivered several blows to their victim’s head and body. Steele gave a loud groan, and then a little afterwards another, after which he appeared to be dead. Hanfield, who was on his knees holding the man’s legs, became suddenly alarmed for his own safety. He got up and said, ‘John, you have killed the man,’ to which Holloway retorted that he was lying as the victim was only stunned. At this Hanfield said he would leave, and did so, walking back towards Hounslow, while Holloway and Haggerty remained with the body.

Despite his eagerness to get away from the scene of the crime, Hanfield waited for his companions outside The Bell, and about an hour later the two appeared looking out of breath. Holloway was carrying a hat, a rather better quality one than the one he had been wearing, which had looked like a solder’s hat and which he said he had destroyed and left behind. The three arrived at the Black Horse after midnight, finding the house shut for business but the landlord not yet in bed. They were able to obtain a drink, and shared half a pint of gin before parting for the night.

When they saw each other the next day Holloway was wearing the stolen hat, which was a little too small for him. On the following Monday he still wore the hat, which worried Hanfield as he thought it might lead to them being discovered. Looking into the hat he saw that the name of Steele was marked inside it, and pointed this out to Holloway, who promised to get the lining taken out. Holloway later told Hanfield that he had tied the hat in a handkerchief weighted it with stones and thrown it off Westminster Bridge.

After telling his story, Hanfield was taken to the heath by Vickery together with Mr Hughes and Isaac Clayton. Alighting from the coach at The Bell, Hanfield was told to walk where and how far he wished. Approaching the 11-mile stone, he pointed to the clump of trees where the body had been found.

Holloway, a stoutly built man, was arrested by Joseph Dunn, the parish officer of Paddington, and taken to Clerkenwell Prison. On the following day Vickery and an officer of Worship Street, Daniel Bishop, took him to court, after first reading to him the warrant charging him on suspicion of the murder of Mr Steele. ‘Oh, dear!’ exclaimed Holloway, ‘I know nothing about it, I will down on my knees to you and the justice, if you will let me go.’

On 29 November Vickery arrested Haggerty, who was then aboard a frigate moored off Deal. Haggerty, who was slightly built, was too ill to be told the reason for his arrest. He was let down out of the ship into a boat, assisted by the nervous Vickery, who was unsure that the man would live long enough to reach London. That same morning Haggerty, whose voice was so faint he could hardly be heard, was questioned by the port admiral. Haggerty said that he had been a marine for two years, but could not remember where he had been three years ago. Asked about his movements four years ago, he failed to answer and almost fell. Vickery had to catch him, and he was allowed to sit and was given some water. Haggerty was too ill to travel and had to be left behind at Deal Hospital.

On 8 December Holloway and Haggerty appeared at Worship Street and were questioned by the magistrate, John Nares. Hanfield’s statement was read to the two prisoners, who were questioned separately. Both men said they did not know each other, and were entirely innocent of the murder.

The murder of John Cole Steele from the Newgate Calendar.

Holloway, who was generally known under the name of Oliver, said that Hanfield was ‘an entire stranger’ and pointed out that in the statement made against him Hanfield had given the wrong name. He knew nothing of Hanfield, having only seen him in the street. He denied ever having been in Hounslow and said that in November 1802 he had been working for a Mr Rhodes and a Mr Stedman. Haggerty, who said that he knew no more of the offence ‘than a child unborn’, accused Hanfield of confessing only to get his freedom, and pointed out some minor contradictions in the accounts he had given at different times. He said he was never in Hounslow in his life, and in the winter of that year was working for a Mr Smith of Seven Dials.

The magistrate questioned the men whom the suspects said had employed them, but all denied that the accused had worked for them in 1802, although they had done so in other years. Some effort was made to show that Mr Steele’s hat or boots might have fitted the prisoners but this was inconclusive.

Holloway and Haggerty were questioned seven times in all, and between these sessions they were confined in separate cells, with a partition sufficiently thin that they were able to converse with each other. Unknown to either, Officer Daniel Bishop was placed in a nearby privy from where he was able to overhear what they said.

The trial of John Holloway aged thirty-nine and Owen Haggerty, twenty-four, took place at the Old Bailey on 18 February 1807. The chief witness for the prosecution was Benjamin Hanfield, who had earned his immunity from prosecution. Before he gave evidence a portion of His Majesty’s pardon was read out in court.

The defence took the line that Hanfield had only confessed for personal gain, and suggested that when in gaol Hanfield had boasted that he knew a way of getting his liberty and putting £500 in his pocket. Hanfield replied that the only mention he had made of £500 was to Mr Shuter the head turnkey when he had said that he was due the sum from a legacy but would not be able to get it. He insisted that his only motive in telling what he knew was ‘compunction of conscience’. He said that no promises had been made to him to induce him to make his statement, and denied that he had ever informed against anyone for reward. Shuter later testified that he had never discussed the crime with Hanfield.

Hanfield, saying that he thought the murder was a cruel thing which had greatly troubled his conscience, admitted that despite this he had said nothing about it and had made no written note of what had happened during the four years that had elapsed since the crime. He had heard about Steele’s family offering a reward of £50 but had not made any disclosure then. Despite the obvious suspicions about his motives, the impression made upon the court was that Hanfield knew a great deal about the murder.

Hanfield’s story about the passing coach was supported by coachman John Smith, who testified that he drove the Gosport coach which left London at 6 p.m., arriving at Hounslow two hours later. The coach had left Hounslow on 6 November and was between the clump of trees and the 11-mile stone when he heard the sound of a man moaning in distress. The sound came from the north side of the road. He heard the groaning again, fainter than at first. Smith remarked to the passengers that he thought something was amiss, but he didn’t stop.

Mr Gleed, for the defence, then observed that it was unnecessary to call any more witnesses to prove that Mr Steele had been murdered at that spot. ‘There is no doubt that the witness, Hanfield, had a hand in the murder;’ he said. ‘The question is whether the prisoners at the bar had and whether they were the perpetrators of it or not …’

Joseph Townsend, a Bow Street officer, was able to produce the original items of evidence; the shoes, the hat and the stick, which he described as a bludgeon, and the strap.

Although Holloway and Haggerty had claimed as part of their defence not to know each other or Hanfield, there were many witnesses who had known all three men for a number of years. There was clear evidence that the two prisoners knew each other, but their connection with Hanfield was less obvious, and many of the sightings were several years old. William Blackman testified that the two accused had been in each other’s company often for the last four or five years, and four years ago he had seen all three together, yet he also said that he had only known Holloway for a year and a half. Edward Crocker, a Bow Street officer, said he had often seen Holloway and Haggerty in public houses in Dyott Street, and that Haggerty owned a blackthorn stick.

Christopher Jones, another Bow Street officer, said he had seen Haggerty and Hanfield together in different public houses and in the streets about three years ago. Collin M’Daniel, the publican of the Black Horse, said he had seen Hanfield and Haggerty travelling together, but this was about ‘three or four or five years ago’. William Beale of the Turk’s Head knew all three men and although he had never seen them all in company, Haggerty and Hanfield had both been at his house at the same time, though not drinking together. John Peterson, a porter, had often seen Haggerty and Hanfield at the Turk’s Head, where he had served them with beer. What was unclear from much of the evidence was whether Hanfield and the accused had actually been in each other’s company or whether they had simply been customers in the same public houses or in the street at the same time.

John Sawyer had lived at The Bell, Hounslow in 1802, but could only say he thought he had seen Holloway at Hounslow.

Officer Daniel Bishop now supplied the court with some extraordinary testimony. He claimed to have written down verbatim all the conversation that took place between Holloway and Haggerty which he had overheard from the privy, and read it out. It was obvious from his evidence that the two men knew each other well and were friends and had both lied when they had claimed not to know each other. In these reported conversations the prisoners had said that Hanfield was a lying villain and both were convinced that his evidence would not be accepted. Up to the time they were committed for trial they had felt that the most likely outcome was that their accuser and not they would suffer for the crime. Nothing in their conversation suggested that they had any complicity in or knowledge of the crime.

At the close of the trial it was apparent that Hanfield’s evidence had been accepted as true, and the prisoners’ failure to provide an alibi, as well as the lies they had told, had counted against them. Both were found guilty. When questioned further in prison they continued to assert their innocence. Hanfield disappeared. His subsequent career is unknown.

The execution of Holloway and Haggerty took place outside Debtors’ Door of Newgate Prison on Monday 23 February, together with that of Elizabeth Godfrey for the murder of Richard Prince, whom she had stabbed in a quarrel.

The crowds that assembled were unparalleled and estimated at about 40,000 people. By 8 a.m. there was not an inch of ground around the scaffold unoccupied. Even before the prisoners arrived the crush was so great that people trapped in the crowd were crying out to be allowed to escape. When Holloway was brought out and pinioned he fell to his knees and protested his innocence. Rising, he proclaimed that both he and Haggerty were innocent of the crime. The frailer Haggerty declared the same. When Holloway ascended the platform, ‘seemingly with an undaunted spirit’, he bowed first to the left then to the right and addressed the multitudes: ‘Innocent! Innocent, Gentlemen! No verdict! Innocent, by God!’ Even after the cap was placed over his head he continued to repeat the word ‘Innocent’. As the fatal moment approached the crowds surged with excitement.

At the corner of Green Arbour Lane, nearly opposite the Debtors’ Door, two piemen were selling their wares when one man’s basket was knocked over. He was bending down to pick up his wares when the surging crowds tripped and fell over him. There was an immediate panic, in which people fought with each other to escape the crush. It was the weakest and the smallest in the crowd who suffered. Seven people died from suffocation alone, and others were trampled upon, their bodies mangled. A broker named John Etherington was there with his twelve-year-old son. The boy was killed in the crush, and the man was at first thought to be dead and placed amongst the corpses, but he survived with serious injuries. A woman with an infant at her breast saved her baby by passing it to a man and begging him to save its life. Moments later she was knocked down and killed. The baby was thrown from person to person over the heads of the crowd and was eventually brought to safety.

The condemned cell, Newgate Gaol.

As the drop of the platform was struck away the three condemned fell, and were left to strangle to death. Gradually the mobs dispersed, and the bodies, thirty in all, were taken up in carts, twenty-seven to Bartholomew’s Hospital, two to St Sepulchre’s Church and one to The Swan public house. Numerous others were injured, including fifteen men and two women who were so severely bruised that they were taken to hospital, one of whom died the following day. At the hospital, the bodies were washed and laid out in Elizabeth ward, awaiting identification by relatives.

Dead Man’s Walk, Newgate Gaol.

The trial left behind considerable unease, and real doubts as to whether the evidence of Hanfield could be relied upon. Attorney James Harmer had been asked by the fathers of the accused to instruct counsel to defend them. At first he had been in no doubt as to their guilt, but as the trial had progressed he began to have misgivings. He spoke to Holloway and Haggerty many times after the trial and became convinced of their innocence. In 1807 he published a pamphlet making a number of points which suggested that Hanfield had lied. Harmer observed that at the trial Hanfield had said that he had seen Steele walking on the ‘right side of the road going from London’ i.e. the north side, the side on which the body had been found. Harmer made enquiries and discovered that Steele habitually walked on the south side of the road. He theorised that Steele had been attacked on the south side and had run from his attackers in the direction of the barracks on the north side hoping to get help.

An execution at Debtors’ Door, Newgate Gaol.

Harmer spoke to the landlord of The Bell and his wife, who did not recall any strangers being in their house on the night of the murder, and neither did the landlord of the Black Horse recall being woken at midnight that night. Hanfield had claimed to be a hackney-coach man, but Harmer found that he had actually been a guard on the stagecoach on the Hounslow Road and also a soldier at Hounslow barracks, and was well acquainted with the area. The facts of the murder – where it had occurred and what articles were found nearby – were well-known through local gossip. Hanfield’s evidence about Holloway wearing Steele’s hat was not borne out by anyone else. Harmer also observed that as Steele had no routine there was no way that the men could have known of his journey that night. The stick found on the heath was not blackthorn, as described by Hanfield, but birch. When Harmer examined Hanfield’s evidence carefully he realised that it lacked small detail. For the period immediately after the murder Hanfield had nothing at all to say, claiming that he had left the scene. Harmer was sure that this was to conceal the fact that he actually knew nothing about the crime apart from common gossip, because he had not been there.

Most damningly, Harmer found that Hanfield had tried the confession trick before. In 1805 he had been charged with desertion from the 9th Light Dragoons and had calculated that by confessing to a robbery he would avoid being returned to his regiment to be punished for desertion. When he confessed before the Bow Street magistrates, however, it was so obvious that he knew nothing of the burglary that he was acquitted and was later confined to military prison.