13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

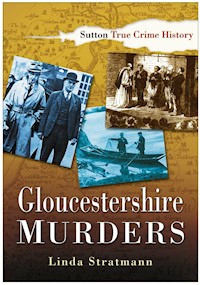

Contained within the pages of this book are the stories behind some of the most notorious murders in Gloucestershire's history. The cases covered here record the county's most fascinating but least known crimes, as well as famous murders that gripped not just Gloucestershire but the whole nation. From the Cheltenham torso murder to the Campden Wonder, when William Harrison returned to Chipping Campden after three people were executed for killing him; from a fatal battle between poachers and gamekeepers near Berkeley to poisoning in the Forest of Dean, this is a collection of the country's most dramatic and interesting criminal cases.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Gloucestershire

MURDERS

Linda Stratmann

To Gail

First published in 2005 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted in 2013 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Linda Stratmann, 2013

The right of Linda Stratmann to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8453 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.The Campden Wonder

Chipping Campden, 1660–2

2.Legacy of Death

River Severn, 1741

3.A Shot in the Dark

Catgrove Wood, Hill, near Berkeley, 1816

4.Revelations

Newent, 1867–72

5.Triple Event

Arlingham, Stapleton and Gloucester, 1873–4

6.Virtue and Sin

Oakridge Lynch, 1893

7.The Mad Cyclist

Horsley and Saddlewood, 1902

8.The Poisoning of Harry Pace

Fetter Hill, near Coleford, 1928

9.The Torso in the River

Tirley and Cheltenham, 1938

10.Strange Practices

Henleaze, Bristol, 1946–7

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my very grateful thanks to everyone who has assisted me with my research for this book, including all those who helped to make my time in Gloucestershire an enjoyable and fruitful one.

As always, the staff in my old haunts of the British Library, Colindale Newspaper Library, the Family Record Centre and the National Archives were immensely helpful.

Special thanks must go to: Robert and Elaine Jewell of St Augustine’s Farm, Arlingham, for their enthusiasm and assistance with photographs; Keith and Ken Jones, West End Farm, Arlingham, for some delightful hospitality, and permission to photograph the scene of the crime; Sarah Manson of the Scribe’s Alcove website www.scribes-alcove.co.uk for advice about the location of Catgrove Wood; and Mrs Frances Penney of Newent. Our serendipitous meeting with Mrs Penney in the graveyard of Newent church was a happy moment which led to a fascinating afternoon that I shall always remember. Her contribution to my research was of immense value.

INTRODUCTION

Gloucestershire is a county of enormous contrasts. Bisected by the great estuary of the Severn, it boasts rich farmlands, dramatic hills, peaceful villages of honey–coloured Cotswold stone, a legacy of silk and woollen mills, and the mines and quarries of the Forest of Dean. For many years Bristol was a part of the county, and its thriving trade and expanding population made it the second city in England.

Murder, too, can come in many guises: a moment of passion; a carefully executed plot; a pitched affray at the dead of night; and sometimes a murder that may have been no murder at all. Not all of the cases in this book have been solved, and many leave us with fascinating questions to engage our minds long after we first encounter them.

In my research I have made extensive use of contemporary documents, including trial transcripts, newspapers, the records of Assizes, the Metropolitan Police and Director of Public Prosecutions held in the National Archives, and family history archives. I especially appreciate the invaluable local knowledge provided by the friendly and welcoming people of Gloucestershire.

1

THE CAMPDEN WONDER

Chipping Campden, 1660–2

Chipping Campden is a small market town built of honey-coloured stone, lying on the edge of the Cotswold Hills. Many of its buildings date back to the fourteenth century, when the town first became of note through its connection with the wool trade. By the seventeenth century that trade was in decline, and the town settled into a more peaceful mode of life, only to be disturbed by a series of events at once dramatic, tragic and inexplicable.

The Manor of Campden was purchased in 1609 by Baptist Hicks, a Gloucestershire man who had amassed a great fortune through trade. A generous man, he built a row of substantial almshouses in 1612 and a market house in 1627. In 1613 he built himself a noble house near the church, the outside of which was reputed to have cost him £29,000, a sum equivalent to about £3.5 million today. There he ordered lights to be set up on dark nights for the benefit of travellers. In 1628 he was created Viscount Campden of Campden, but having no son to inherit his fortune and title, he procured a special licence by which all his honours and titles passed on his death in 1629 to the Noel family, Sir Edward Noel being the husband of his eldest daughter, Juliana. Edward Noel died in 1643 and the title passed to his son, Baptist Noel. The Hicks and Noel families were ardent Royalists during the Civil War, and the manor house served as a garrison for the King’s men. When they were forced to quit it, however, they were afraid that it would fall into the hands of the Parliamentarians, and rather than have this happen the house was deliberately burned to the ground. Only some outlying buildings survived, including the gateway, the stables, which were later converted into accommodation for Lady Juliana, and the East Banqueting Pavilion.

Memorial to Lord Edward and Lady Juliana Noel, St James’s Church, Chipping Campden. (Author’s collection)

It is probable that in 1660, when the extraordinary events that came to be known as the Campden Wonder started to unfold, Lady Juliana, who was then about 74 years of age, was not living in Campden but at the Noel family estates in Rutland. She still retained an interest in the Campden estate and employed a trusted steward, William Harrison, to collect the rents. In 1660 Harrison was about 70 years of age, and he had served the Noel family for fifty years. It is thought that he was then living in one of the remaining outbuildings of the estate, quite probably the East Banqueting Pavilion. Harrison, a respected man in the community, was a feoffee – a governor – of the Chipping Campden Grammar School, the accounts of which provide samples of his signature. Another feoffee was local magistrate Sir Thomas Overbury, whose uncle and namesake had come to an unfortunate end in the Tower of London in 1613. It is to Overbury’s account of the Campden Wonder, written many years after the events, that we are chiefly indebted for the story.

In 1660 the legal and political affairs of the country were in a state of turmoil. Richard Cromwell had ceased to act as Lord Protector in May 1659, and the judges he had appointed were no longer in office. New judges had been appointed by the Long Parliament, but after this was dissolved in March 1660 it was uncertain whether their decisions remained valid. Charles II was not declared lawful king until 8 May, and even after that the restoration of the monarchy was still in doubt until Charles arrived in London three weeks later. Although the King’s new parliament promised to pass an Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, pardoning offences committed during the conflict (apart, of course, from those connected with his father’s death), it was by no means certain that this would happen, and the matter was hotly debated for the next three months.

On the afternoon of Thursday 16 August 1660 William Harrison set out to walk from Campden to the village of Charringworth 2 miles away to collect the rents. He first collected £23 from Edward Plaisterer, then called at the house of William Curtis, but Curtis was out, and Harrison did not wait for him. Turning homewards, he stopped at the village of Ebrington, which was mid-way between Charringworth and Campden, where he paid a brief visit to the home of one of the villagers, called Daniel. After that he disappeared. Mrs Harrison, waiting at home for her husband’s arrival, began to worry about him as the evening wore on, and between 8 and 9 p.m. sent her servant, John Perry, to look for his master. Neither man returned that night.

At the time of these events John Perry was about 25 years old and had probably served the Harrison family since boyhood. His mother, Joan, had been widowed about three years previously. John had one surviving brother, Richard, and several sisters. Richard, seven years John’s senior, had effectively been head of the family since his father’s death and was married with children, whereas John was single.

Campden House and Estate before 1645, from a contemporary drawing. (British Library)

Early on the morning of 17 August Edward, William Harrison’s son, went out to trace his father’s footsteps and on the way to Charringworth encountered John Perry, who informed him that his master was not there. The two men went to Ebrington, where they spoke to Daniel. Half a mile away was the village of Paxford, where they made enquiries, but Harrison had not been seen there. The trail had gone cold. Turning their steps towards Campden again, the men must have anxiously questioned everyone they met on the way, and were told of a hat, collar band and comb that had been found in the road between Campden and Ebrington by a poor woman who had gone to glean in a field. They at once went to look for the woman and, finding her, were able to confirm that the items were the property of William Harrison. Disturbingly, they had been much hacked and cut about, and there was blood on the collar. Edward now felt sure that his father had been attacked and murdered, probably by robbers, and asked the woman to show them where she had found the items. She led them down the roadway near a bank of gorse bushes. A search was made, but there was no trace of the missing man.

Suspicion naturally fell on John Perry, who had thus far failed to explain why he had stayed out all night. On the following day he was examined before a Justice of the Peace, who was not named in Overbury’s pamphlet but may have been Overbury himself, which would account for his detailed knowledge of the case. Perry said that having travelled a land’s length (a furlong, or 201m) on his way to Charringworth, he had met William Reed of Campden, and told him of his errand. He told Reed that he was afraid, as it was growing dark, and thought he would return, fetch his young master’s horse (presumably Edward’s) and come back. The two men walked to Harrison’s court gate (probably the gate leading to the courtyard of the old Campden House). There the two men parted, Reed going his own way, but Perry, for reasons he never explained, did not go to get the horse, but stayed where he was. A man called Pearce next happened by and Perry walked with him into the fields for a ‘bow’s shot’ (about 200 yards) before returning with him to his master’s gate, where they parted. By now, Perry’s wanderings back and forth and standing around had occupied two hours, during which Mrs Harrison no doubt thought he was searching for her husband. Perry then went into his master’s hen-roost and lay there for an hour, without sleeping. When the church clock struck midnight he got up and went towards Charringworth. Then, he said, a great mist arose and he lost his way, so he spent the rest of the night lying under a hedge. At daybreak he continued his journey to Charringworth, where he spoke to Edward Plaisterer and William Curtis. By now it was 5 a.m., and the sun was rising, so Perry set out for home, meeting up with Edward Harrison on the way.

At first glance Perry’s tale looks highly suspicious; however, all the four men he mentioned supported what he had said as regards themselves. The Justice asked him how come he was so bold as to go to Charringworth at midnight when he had been afraid to go there at nine? Perry replied that he was afraid at nine because it was dark, whereas at midnight there was a moon. Records show that moonrise that night was at about 10.30 p.m., so we can assume that at midnight the moon was well risen and bright. The Justice also asked him why, having twice returned home, did he not think to go into the house to see if his master had returned while he was out? Perry said that he knew his master was not home as there was a light in his chamber window which never used to be there so late when he was at home. It is possible that Mrs Harrison had placed a light in the window to help light her husband home. Harrison usually retired to bed early, so had he been home the light would have been out. It does seem strange that Perry, who was born and bred in Chipping Campden, managed to lose his way, even in the mist, but he was clearly unwilling to go about when he could not see his way. All his odd behaviour can be accounted for by fear of the dark. His waiting around was for enough moonlight to travel by, and he at once attached himself nervously to any passer-by who would keep him company.

Perry was kept in custody pending further enquiries. He remained in Campden either at the inn or in the common prison from Saturday 18 August to the following Friday. During this time the same Justice questioned him again, but his story remained the same. It was later rumoured that, being often pressed to tell all he knew, he had satisfied his listeners with more than one story, telling some that his master had been killed by a tinker, others that a gentleman’s servant of the neighbourhood had robbed and killed him, and still others that he had been killed and his body placed in a bean-rick. The bean-rick was duly searched but nothing was found.

Eventually, Perry stated that if he could speak to the Justice again he would tell him something that he would say to no one else. On Friday 24 August he was brought before the Justice and said that his master had been murdered, but not by him. The murderers, he said, were his own mother and brother. The Justice, shocked at this unexpected revelation, quite rightly cautioned him, saying he feared that John might be the guilty one, and asked him not to draw more innocent blood on his head, for the charge might well cost his mother and brother their lives. Perry stuck to his story. He said that ever since he had been in service with Mr Harrison, his mother and brother had pestered him to tell them when his master went to collect the rents so they could waylay and rob him.

John then launched into a detailed description of the murder of William Harrison. He said that on the morning of Thursday 16 August he had gone into town on an errand. There he met his brother, Richard, in the street and set matters in motion by telling him where Harrison was going that day. That evening, after being sent out to look for his master, he had met Richard again by Harrison’s gate, and they walked together to the churchyard. There they had parted, John taking the footpath across the churchyard and Richard keeping to the main road around the church. Why they should have parted at this point John never explained, but a search for Harrison seems the most likely motive. In the highway beyond the church the brothers met up again, and walked to the gate a bow’s shot from the church that led into ground belonging to Lady Campden called the Conygree. For anyone who held a key to the gate, which his master did, it was the quickest way to Harrison’s house. John said he had seen someone, who he assumed was his master, go into the Conygree and told Richard that if he followed he would have the money. Declining to take part in the crime himself, he went for a walk in the fields. After a while he followed his brother into the Conygree, and there found his master lying on the ground, Richard standing over him and their mother standing nearby. ‘Ah, rogues, will you kill me?’ Harrison had exclaimed. John told his brother that he hoped he would not kill his master, but Richard said, ‘Peace, peace, you’re a fool’, and strangled Harrison. He then took a bag of money from Harrison’s pocket and threw it into his mother’s lap. John and Richard carried the body from the Conygree to the adjoining garden, where they discussed what to do with it. They decided to throw it into the ‘great sink’ (probably a cesspool) by Wallington’s Mill behind the garden. Richard and his mother sent John to the court next to the house to listen if anyone was stirring, but he chose not to return to them, going instead to the court gate where he encountered John Pearce, as mentioned in his original statement. John Perry had with him his master’s hat, band and comb; later, after giving them some cuts with his knife, he threw them on the highway, where the poor woman found them, so as to make people think his master had been robbed there.

The East Banqueting Pavilion, Chipping Campden. (Author’s collection)

The strange thing about Perry’s tale which no one seems to have commented on at the time was that Harrison was said to have returned home well after Perry was sent to search for him, in other words when he had already been missing long enough for his wife to be worried.

On hearing this story the Justice had no option but to give orders for the arrest of Joan and Richard Perry, and for the sink to be dragged for the body. No trace of Harrison could be found, however, either there or in the fish ponds, or in the ruins of Old Campden House, all of which were thoroughly searched.

On Saturday 25 August all three Perrys were brought before the Justice, where Richard and Joan indignantly denied all the charges. Richard agreed that he had met his brother in town on the Thursday in question, but that their conversation was nothing to do with Harrison’s going to Charringworth. He and his mother now rounded on John, saying he was a villain to tell such lies, but John stuck to his story.

As the three prisoners were returning from the Justice’s house to Campden, Richard pulled a cloth from his pocket and with it came a ball of inkle, a kind of linen tape. One of the guards picked it up and Richard explained that it was a hair-lace belonging to his wife. Noticing that the length of inkle had a slip knot in it, the guard showed it to John and asked whether he knew it. John shook his head sorrowfully and said that he did, for that was the string his brother had used to strangle his master.

The next day being Sunday, the Minister of Campden (probably the Revd William Bartholemew) asked to speak to the prisoners, and they were brought to the church. On the way they passed Richard’s house, and two of his children went out to meet him. He took the smaller in his arms and led the other by the hand. Suddenly, both started to bleed at the nose, an event which was seen as ominous.

The Justice, having thought over the statements made by John Perry, now recalled some unusual events in the recent past which he thought might be related to Harrison’s disappearance. In the previous year Harrison’s house had been burgled, between eleven and twelve noon, on Campden market day when all the family was out. They had returned home to find leaning against the wall a ladder leading to a second-storey window. The window had been barred with iron, but the bar had been wrenched off with a ploughshare, which was later found in the room. A sum of £140 was missing. The culprits were never found.

More recently, only a few weeks before Harrison’s disappearance, John Perry had been heard making a huge outcry in the garden. He had come running out in a great state of alarm with a sheep-pick (a pitchfork) in his hand, saying he had been set upon by two men in white with naked swords, and he had defended himself with the sheep-pick. The handle of the implement was cut in two or three places and a key in his pocket was also cut, which he said had been done with their swords. He himself seemed to be uninjured.

John Perry was closely questioned about these two incidents and said that it was his brother who had committed the burglary. He said he had not been there at the time but he had told his brother where the money was kept and where he might find a ladder. Richard had afterwards told him he had buried the money in the garden. The attack on himself he confessed to being a fiction, to make people think that rogues haunted the place, so that when his master was burgled it would be thought they had done it. The Justice ordered a search to be made for the money, but nothing was found.

While the prisoners awaited trial an event happened that was to have an important effect on the outcome of their case. On 29 August 1660 the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion was finally passed. At the assizes in September Joan, John and Richard had two indictments found against them; one was for the burglary and the other for the murder of William Harrison. The judge of the assizes, who is generally thought to have been Sir Christopher Turnor, an eminent and highly respected man, refused to try the Perrys on the second count, as no body had been found, but they were then tried for the burglary. All three initially pleaded not guilty, but at this some whispering was heard behind them; after some consultation they changed their plea to guilty but begged the benefit of the pardon conferred by the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, which applied to the 1659 burglary, although it could not apply to the more recent charge. It is very probable that they had been advised by their lawyers to make this plea in order to save the time of the court. It was, as it turned out, a fatally bad piece of advice. All three were granted a pardon under the new Act, although after the trial they continued to deny any guilt in or knowledge of the burglary. In the meantime, John Perry continued to say that his mother and brother had murdered Harrison. He also accused them of trying to poison him while he was in the jail, so that he dared not eat and drink with them.

The Perrys remained in jail until the next assizes the following spring, when the murder indictment was placed before a different judge, Sir Robert Hyde, who was known for his severity. All three pleaded not guilty to the murder, and John retracted his accusation, saying that when he made it he was mad and had not known what he was saying. Since none of John’s several accounts of his master’s death or the details he had given of the burglary had been supported by any evidence, there were good grounds for belief that nothing he said should be given any credence. Richard and Joan said they knew nothing of what had happened to William Harrison, and Richard pointed out that John had accused others, too, though no names were placed before the court. Unfortunately, all three were now considered to be proven criminals after pleading guilty to robbery, and Hyde was not so particular about the fact that no body had been found. The Perrys were found guilty of the murder of William Harrison and sentenced to hang.

A few days later all three were brought to the top of Broadway Hill near Campden, where a gibbet had been erected. Edward Harrison stood at the foot of the ladder to observe the executions. As it was rumoured that Joan was a witch and that her sons would be unable to confess while she was alive, she was executed first. With his mother’s body dangling from the gibbet, Richard was next to ascend the ladder. As he did so, he professed his innocence and said that he knew nothing of what had become of Mr Harrison. In his final words he beseeched John for the satisfaction of the whole world and his own conscience to declare what he knew. John, with a dogged and surly manner, told the watching crowds that he wasn’t obliged to confess to them. Richard was hanged, and as John prepared for death there must have been some anticipation that he would at last resolve the mystery. Disappointingly, he said that he knew nothing about his master’s death, or what had become of him, though he hinted that they might possibly hear something in years to come. He died without a confession. The bodies of Joan and Richard were later taken down and buried near the place of execution, but John’s was left to hang in chains.

Two years passed, and the body of John Perry had rotted where it hung, when William Harrison returned to Chipping Campden. The reaction of his family and friends has not been recorded, though it is easy to imagine delight and amazement at his appearance being mingled with sickening guilt. He resumed his previous duties, including the governorship of the school, where a comparison of his signatures with the accounts before and after the incident can leave no doubt that this was indeed William Harrison. He claimed in a letter to Sir Thomas Overbury to have been attacked by strangers, stabbed in the side and thigh with a sword, and abducted. Money had been stuffed in his pockets, and he had been carried on horseback to Deal on the Kent coast, where he had been placed on board a ship bound for Turkey. He was there sold for £7 as a slave to an elderly physician and remained there until his master’s death almost two years later. He then found a ship going to London and returned home.

Broadway Tower, built in 1799 on the site of the execution of the Perrys. (Author’s collection)

The story is ridiculous on several counts. Who would abduct a man of 70 in order to transport him overseas and sell him as a slave for a few pounds? Why was he wounded, requiring his captors to spend much time and trouble nursing him back to health? Why was money stuffed in his pockets? How was he transported on horseback from Gloucestershire to Kent without anyone noticing? An account of the incident and a ballad, both published in 1662 by Charles Tyus, who was unwilling to admit that three innocent people had been executed, stated that Harrison had indeed been attacked and robbed by the Perrys, who flung him into a pit, but once he recovered his senses, Joan Perry’s witchcraft had instantly transported him from the spot. Even Harrison had never suggested that the Perrys had anything to do with his missing two years.

The Campden Wonder leaves us with two great mysteries – what happened to William Harrison, and how do we explain John Perry’s behaviour?

The most probable reason for William Harrison’s disappearance was that he deliberately faked his own death after embezzling funds belonging to Lady Campden, something which could have gone on for many years. The restoration of the monarchy, the return to order and the appointment of king’s judges could well have made him fear discovery. It is unlikely that he even left the country, but took with him such funds as he had in order to make a new life. He may never have intended to return to Chipping Campden, but was forced to when his money ran out. Whether he knew anything of the fate of the Perrys, it is impossible to say.

Did Mrs Harrison know her husband’s secret? Anthony Wood, an Oxford antiquary and contemporary of Overbury, wrote some notes on a copy of Overbury’s account held in the Bodleian Library, in which he claimed that after Harrison’s return his wife, ‘being a snotty covetuous [sic] Presbyterian’, hanged herself. Another edition of Overbury’s pamphlet in the Bodleian has a letter attached, dated 1780, from a Charringworth man, Mr Barnsley, to antiquary John Gough, stating that after Harrison’s return Mrs Harrison hanged herself, and a letter was later found in her effects written by her husband before the execution of the Perrys. The inference is that Mrs Harrison stayed silent to protect her husband, and knowingly allowed three innocent people, all of whom she must have known, to go to their deaths. On her husband’s return guilt, and maybe local gossip, drove her to suicide. It is impossible to confirm whether these stories are true or just inventions intended to add drama to an already tragic tale. Since Mrs Harrison’s Christian name is unknown and the surname was a common one in the area, it is not possible to discover her date of death. It has also been suggested that Edward Harrison was in some way involved, wanting to remove his father so he could gain the stewardship, which he later did, but there is no evidence for this.

Wood, who was perhaps repeating local rumours, added a fanciful tale about a gentlewoman who ordered Joan’s body to be dug up, so she could learn more about witchcraft. When her horse shied away from the body she struck her head on John’s dangling feet and fell into the grave. Wood also alleged that on Harrison’s return a messenger brought the news to Sir Robert Hyde, the judge at the Perrys’ murder trial, who accused him of lying and had him flung in prison. Whether this is true or not, it certainly says something about opinions of Hyde’s administration of justice.

It is too easy to suggest that Perry was mentally subnormal or simply insane. One popular theory is that he was schizophrenic and subject to delusions; however, he had worked for Harrison for some time, was trusted enough to be sent out to find him, and his evidence is detailed and coherently given. Had he been ‘simple-minded’ or obviously delusional, this would have been well known locally and would probably have emerged at the questioning. That said, there is some evidence of a personality disorder, which took the form of attention-seeking behaviour arising out of a feeling of inadequacy. Nothing is known of such behaviour in his early life, but there are some very striking incidents that suggest Perry was adept at using events to place himself at the centre of attention, either in a heroic role or as a victim.

Signatures of William Harrison. From top to bottom, 9 April 1657, 5 April 1660 and 15 October 1663. (Chipping Grammar School Accounts Book)

The first such incident is the burglary at Harrison’s house. Perry said nothing about this at the time, but later he accused his brother of the crime and claimed he knew where the money was hidden. One question that should be asked is whether this robbery ever actually occurred. It is supposed to have taken place in broad daylight when the Harrison family was away from home. It would have been simple for Harrison to hide the funds where he could later retrieve them, place a ladder at the window, wrench off the iron bar and claim that he had been robbed.

The second such event is the supposed attack on Perry by the armed men. Such accusations are common among those who seek attention. The ‘ball of inkle’ incident also shows that he was quick-witted enough immediately to turn an unexpected incident to his own account.

It has been suggested that Perry suffered from the disorder that leads people to confess to high-profile crimes but, looking at his statement in detail, we can see that he never actually confessed to the murder. He confessed only to telling his brother where he might find Harrison and also to placing the hat, comb and band on the road. It is very possible that John Perry was under the impression that by giving these details he would find himself not in the dock but in the witness box, with a starring role in the trial, exempt from prosecution, by turning ‘King’s evidence’. When he was accused of murder he retracted his confession and said that he must have been mad when he made his original statement – not what one might expect of someone who was delusional, who would have stuck to the story to the end.

Perry’s behaviour reveals not only a wish to draw attention to himself but also a deep, festering resentment of his mother and brother. Whether this was present in his early years we do not know, but matters may have arisen or been exacerbated on his father’s death, when his brother – a more successful man, married with a family and more respected in Campden than John, who remained a lowly servant – was accepted as head of the family. It may have been, or seemed to John, that Richard was his mother’s favourite. By accusing them both of crimes, John not only achieved the celebrity he craved but also removed the two people he felt had consigned him to an inferior role. The conclusion emerges that John Perry, while not emotionally normal, was nonetheless sane, and when he accused his mother and brother of murder he acted deliberately, knowing exactly what he was doing. He was not expecting the ploy to backfire on him, with fatal consequences, and by the time he retracted his story it was too late.

Did John Perry know about Harrison’s disappearance or even connive at it, placing the hat, comb and band in the road for him? This seems unlikely. Harrison was fully capable of planting the items himself on the afternoon of his disappearance, and if Perry had really known all about it, he would hardly have gone to his death to preserve Harrison’s secret. Perry’s hints of hidden information shortly before he was hanged were just his last stab at celebrity.

William Harrison’s signature continued to appear in the school registers until 1672, in which year it is probable that he died, taking his secrets to the grave.