11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

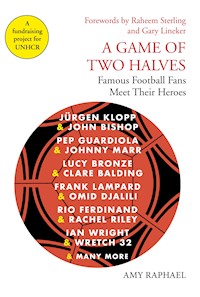

Ever wondered which goal Frank Lampard is proudest of, who Jürgen Klopp thinks will manage Liverpool in the future, what Rio Ferdinand thinks of Man United in the post-Ferguson years or exactly how many grey cashmere jumpers Pep Guardiola owns? In this collection of frank and funny conversations between footballers and their biggest fans, these vital questions (and many more) are finally addressed. A Game of Two Halves shows a different side to some of the biggest names in football, reminding us of the common ground we all share. This project is published in partnership with UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, with the goal of raising both funds for and awareness of their work with child refugees. Featuring forewords by Raheem Sterling and Gary Lineker and interviews between Jürgen Klopp & John Bishop Pep Guardiola & Johnny Marr Lucy Bronze & Clare Balding Frank Lampard & Omid Djalili Rio Ferdinand & Rachel Riley Ian Wright & Wretch 32 Héctor Bellerin & Romesh Ranganathan Steven Gerrard & David Morrissey Gary Lineker & Fahd Saleh Eric Dier & David Lammy John McGlynn & Val McDermid Vivianne Miedema & Amy Raphael

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

A GAME OFTWO HALVES

A GAME OFTWO HALVES

Famous Football FansMeet Their Heroes

AMY RAPHAEL

First published in the United Kingdom by Allen & Unwin in 2019

Copyright © Amy Raphael 2019

The moral right of Amy Raphael to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

‘Refugees’ © Brian Bilston, 2016,is reproduced with the kind permission of the author

All photographs featured herein are the copyright of the contributors, with the exception of the photographs of Gary Lineker on p. 109 (© David Cannon/Getty Images), Jürgen Klopp on p. 155 (© Frm/DPA/PA Images), John McGlynn on p. 185 (© John Marsh/EMPICS Sport/PA Images) and Ian Wright on p. 281 (© Bob Thomas Sports Photography via Getty Images).

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwinc/o Atlantic BooksOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610Fax: 020 7430 0916Email: [email protected]: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 91163 003 6

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76063 656 2

Designed by Carrdesignstudio.com

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Foreword by Raheem Sterling

Foreword by Gary Lineker

Introduction by Amy Raphael

David Morrissey & Steven Gerrard

Romesh Ranganathan & Héctor Bellerín

Clare Balding & Lucy Bronze

Gary Lineker & Fahd Saleh

Johnny Marr & Pep Guardiola

John Bishop & Jürgen Klopp

Val McDermid & John McGlynn

Omid Djalili & Frank Lampard

Rachel Riley & Rio Ferdinand

Wretch 32 & Ian Wright

Amy Raphael & Vivianne Miedema

David Lammy & Eric Dier

Acknowledgments

Refugees

They have no need of our help

So do not tell me

These haggard faces could belong to you or me

Should life have dealt a different hand

We need to see them for who they really are

Chancers and scroungers

Layabouts and loungers

With bombs up their sleeves

Cut-throats and thieves

They are not

Welcome here

We should make them

Go back to where they came from

They cannot

Share our food

Share our homes

Share our countries

Instead let us

Build a wall to keep them out

It is not okay to say

These are people just like us

A place should only belong to those who are born there

Do not be so stupid to think that

The world can be looked at another way

(now read from bottom to top)

Brian Bilston

Foreword by Raheem Sterling

Technically, I, myself, am an immigrant…

And yet when it comes to pulling on a white shirt in front of 90,000 people, I am just as English as the other ten players on the pitch. Game in, game out, I give my all to this country that has offered me so much.

I moved to London from Jamaica when I was five. My mother had moved slightly earlier to secure qualifications, so that she could offer me and my sister a better life. She achieved that, but it wasn’t without hard work and endless sacrifices. The integrity and work ethic she continues to show are part of the reason I have been invited to write this for you today – her values and mental strength are infectious. Throughout my life, my mother has been the definition of integrity. She has helped me grow into the man I am today, unafraid to use my voice to represent those who are very rarely heard.

The estate I settled in after moving to London is shadowed by Wembley Stadium – the home of English football. My home. The team bus drives through areas which hold so many of my childhood memories and I have to pinch myself. How did I get here?! They talk about the American dream; this is the English dream. This is what makes the country we live in so special – we are diverse, we are cultured, but most importantly we are one.

Laziness breeds stereotypes. Every single one of us brings something to the table and everyone deserves to have their voice heard. I urge you all to just stop. And listen. Ask questions. And get to know those around you. Understand their culture and their background because that level of knowledge is powerful. And with such power we can make real positive change.

Foreword by Gary Lineker

Imagine this: Leicester is bombed and completely destroyed. We are forced to flee elsewhere because our families are being persecuted. Our parents have been killed. We can only leave by boat. It is a risk for our young children, but it is probably their only chance of survival. The sea is freezing cold. The boats are unsteady and unsafe. More family members die on the journey. The lucky few make it to the shore of another country. We have risked our lives to get there, but we find we are not wanted.

As soon as I started reading refugees’ stories a few years ago, my conscience kicked in. Most of those who flee their countries don’t choose to leave; they are political or economic refugees who desperately miss home. Feeling empathy for fellow human beings who have been dealt a really rotten hand is not a weakness. Fearing the arrival of refugees in your country does not make you patriotic, it makes you mean-spirited.

I don’t regret tweeting my support for refugees, but it’s a shame that Twitter pigeonholes those of us who speak out. We are judged as being on the extreme left or right, whereas I think most of us are somewhere in the middle. I do occasionally offer my political thoughts, but I don’t think the refugee situation is political, it’s humanitarian.

Some of the treatment of young migrants arriving in the UK has been heartless. I, for one, don’t want to live in that kind of fractured society. And, unfortunately, some of those attitudes have been spilling out into the stands of football grounds. As Raheem Sterling has discovered, one of the most straightforward ways to answer the abuse coming from a minority of fans is by scoring goals. He deserves every accolade that has come his way this season – and none of the abuse.

There are more than 3.5 billion football fans in the world. At its best, football is about a shared language, respect and the celebration of diversity, as the footballers and managers in this book illustrate. Football can bring people together and, in doing so, it can set a really good example. I do believe that football gives back to society by doing that and by lifting people’s lives.

When approached to write the foreword to A Game of Two Halves, I didn’t hesitate because we must all find a way to help our fellow human beings. We have to do more to help each other. Reminding people that refugees don’t choose to leave their homes is important and if this book can do that in a small way, it’s a good thing.

Interviewing Fahd Saleh, a former goalkeeper for a team in Homs, Syria, for this book was thought-provoking and inspiring. It was a reminder that some of us are lucky to have been born in a relatively safe place by the lottery of birth. I consider myself fortunate to have played football around the world, to have four healthy sons and to live in a country untouched by war. Lucky, yes. Complacent, never. Call me all the names under the sun. I will never stop being patriotic nor will I stop standing up for refugees. We cannot forget them. They are human too.

Introduction by Amy Raphael

I was in Italy when the news came that we were to leave Europe. I lay awake all night, staring at the polls in the blue light of my mobile. Time passed. Four in the morning. Five in the morning. There was no going back. The 52 per cent had had their say. I flung open the window in a futile attempt to make the world seem bigger. I stared at the mist hanging low over the fields, at the sky streaked pink. I felt untethered, as though Britain had cut the umbilical cord connecting it to Europe.

A few months later, in August 2016, I came across two news stories that stayed with me. The first was a series of photos of Syrian children in Aleppo using a bomb crater filled with rain water as a swimming pool; one image showed a fully dressed boy bellyflopping painfully into the small, craggy hole as his mates looked on. The second was drone footage of kids playing football in Aleppo’s dusty, desolate ruins. Just two lads kicking a ball back and forth with not a single other person in view. I knew millions had fled Syria since the civil war started in 2011, but the empty streets of Aleppo made me wonder exactly how many. So I looked up some statistics.

Over 5.6 million people have fled Syria since 2011. (The pre-war population was around 22 million, so a quarter of Syrians have left their country.)

Millions more are displaced inside Syria.

Around the world, 57 per cent of refugees come from three countries – Syria, Afghanistan and South Sudan.

An unprecedented 70.8 million people are forcibly displaced worldwide, of which 25.9 million are refugees. Half of those are under eighteen. Ergo half of them are children.

Or, to put it in different terms, one person is forcibly displaced every two seconds.

Every two seconds.

And Britain had just voted – among other things – to tighten, if not shut, its borders.

I wanted, like so many, to find a way of keeping the conversation going about displaced people. Why? Because, put simply, Britain thrives on its diversity and multiculturalism. We have, I believe, a global responsibility to look after each other. We are better together.

I thought again of the kids in Aleppo jumping into the makeshift pool, of the boys kicking a ball about a city that used to be thriving. They were doing what children do – trying to bring some normality to their lives despite everything. I recalled footage of kids in refugee camps across the world playing football. Football is the most popular sport in Syria and, indeed, across the world. It’s matched only by the Olympics in terms of its global reach; according to FIFA, the World Cup 2018 was watched by almost half the world’s population. It’s a global sport with a global language.

It’s easy to criticize football because of the sheer amount of money involved in it these days, but it also has a developing sense of social responsibility. Since its inception in 2006, Soccer Aid, an annual televised game in which retired footballers play against celebrities, has raised over £35 million for UNICEF UK. Ten years later, in 2016, Amnesty International started their ‘Football Welcomes’ weekend to ‘celebrate the contribution refugees make to the game’. (By 2019, the British clubs taking part in this initiative had trebled to 160, with free match tickets and stadium tours given to refugees and people seeking asylum.)

You don’t need to look very far to find immigrants playing at the very highest level across the world. Zlatan Ibrahimović, the retired Swedish international who has played for teams including Ajax, Juventus, Barcelona, Milan, PSG, Manchester United and LA Galaxy, has a Bosnian father and a Croatian mother. Kylian Mbappé, the France and PSG striker, is the son of a Cameroonian father and Algerian mother. France, Switzerland and Belgium have teams built on the sons of immigrants – Romelu Lukaku and Vincent Kompany are just two Belgian players of Congolese descent.

As Raheem Sterling writes in his foreword to this book, he too was born outside England. And yet when he pulls on the white shirt emblazoned with three lions, there is no doubt where his allegiance lies.

Trying to work out a way to keep the conversation going about displaced people as we drift away from democracy, I came up with the idea of asking famous football fans to meet their heroes for a charity book that raises money for refugees. Those who agreed to be in the book wouldn’t be given an agenda; if the subject of tightened borders came up, then great. If not, then the fan and the footballer or manager could chat about whatever took their fancy. It was clear, to me at least, that the conversations would never be too far away from politics.

Football is, by its very nature, political. Look at Henning Mankell’s piece for a 2006 issue of National Geographic, in which the Kurt Wallander novelist wrote about visiting Angola in 1987: ‘War could never kill soccer in Angola. The soccer fields were demilitarized zones, and the face-off between teams conducting an intense yet essentially friendly battle served as a defence against the horrors that raged all around. It is harder for people who play soccer together to go out and kill each other.’

In the same issue (devoted to ‘why the world loves soccer’), author Courtney Angela Brkic wrote about a 1990 match between Zagreb’s Dinamo and Belgrade’s Red Star that is widely seen as marking ‘the beginning of Croatia’s war for independence’. And, of course, Diego Maradona’s second goal against England in the 1986 World Cup is arguably the best ever scored on the global stage but will forever be overshadowed by the goal he scored four minutes earlier; the ‘Hand of God’ goal saw the dazzling Argentinian labelled a cheat exacting revenge for the Falklands War that England ‘won’ four years earlier. These stories illustrate how central football can be to people’s way of life, even if lazy journalism all too often portrays the footballers themselves as abandoning their roots.

In the late 1990s, when I was sports editor of Esquire, I wrote two chapters for Perfect Pitch, a series of football books edited by Simon Kuper and Marcela Maro Y Araujo. In one chapter I asked Liverpool midfielder Steve McManaman to give me a tour of the Liverpool he grew up in and, while doing so, he talked passionately about his support of the city’s striking dockers. Meanwhile, his teammate Robbie Fowler was fined for showing a T-shirt supporting the sacked dockers after scoring against SK Brann. In the second chapter, I met former Arsenal manager George Graham in his London flat just after he’d become manager of Tottenham. We talked about tribalism; I’d watched Arsenal v Tottenham in a north London pub a few days earlier and an Arsenal fan had dismissed Graham as a ‘fucking spiv’. By way of response, Graham said, ‘I can understand the fan. But I think this hatred between clubs is sad. Can’t you support one team without hating another?’

When I started work on A Game of Two Halves, I asked Simon Kuper – now a columnist for the FT and author of the award-winning book Football Against the Enemy – about football not only being tribal but also a unifying force. ‘It’s not uncommon for people to support a big club, a small club and a foreign club. Or to follow a player,’ he told me. ‘The whole scene, even in England, is more fluid than people imagine or admit to. Of course football is divisive, but it’s also the only thing that unites people any more. Because of the way we now watch TV or listen to music, there is no longer any communal conversation in most modern nations. But when there’s a big international football match, people will discuss it the following day at the bus stop, in the office, at school. There’s nothing else like it. It’s not so much that we’re polarized, it’s more that we’re atomized. And sometimes football can transcend that atomization, especially during a World Cup.’

I also asked Kuper for a short answer to a very big question: does football improve lives? ‘Supporting a world-class team gives people an enormous feeling of pride and of being connected to people around the world, even though most people never leave their own country. Football gives you release from the pressure and perhaps the misery of life. It allows you to dream.’

Again, my mind flickered back to the images of the kids kicking a ball around in Aleppo. Football allowed them – for a few minutes at least – to dream.

In early 2017, I asked the actor David Morrissey if he would help me to draw up a list of potential fans and footballers for the book and also tell me about the work he does for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, as one of their Goodwill Ambassadors. He agreed and, in March that year, we travelled with UNCHR to Lebanon to meet various Syrian families, including two who had been identified as vulnerable and were due to be resettled in the UK.

On the first day we met families living in an abandoned shopping mall in central Beirut. The air inside the gloomy space was considerably colder than the mild spring air outside. There was one bathroom for nine families with a total of twenty-seven children. Washing was hanging at the end of the corridor and the place was spotlessly clean, but the smell of damp was pervasive; during a recent rainstorm, the entire place had flooded. The families lived in small, windowless shopping units. We sat on the sofa cushions that doubled as beds and drank tiny cups of the strongest coffee while children played with old plastic toys or stared at us, their blank faces impossible to read. The adults all said the same thing: they wanted to go home to Syria and, if that wasn’t possible, they wanted their kids to have a decent education.

We drove across town to an abandoned block of flats to meet the first of the families due to be resettled. Water sloshed down the communal stairs and junk was strewn everywhere, but the couple had done everything they could to make the flat habitable for their young son. Their respective mothers had travelled from Syria on a bus to say goodbye, knowing they might never see their children or grandchild again. The daughter talked eagerly about learning English and her dream of studying to be an architect while her mother wiped away an endless stream of tears. I thought of those who want to close our borders, but I said nothing.

At a community centre in Beirut we spoke briefly to older Syrians who meet once a week to cook and chat and discuss various issues, their eyes dull with disappointment. We were introduced to Syrian kids who jumped from one foot to the other, excited at the opportunity to show off their English. And to teenagers who talked about family members drowning as they tried to get to Greece by boat. ‘It’s not fair that we are seen as terrorists or as dangerous people,’ said one girl. ‘We have done nothing wrong.’ Her friends could only nod in agreement.

The next day, we drove to the Beqaa Valley, where UNHCR and UNICEF have built emergency shelters as a short-term solution to a long-term problem. Every family we spoke to echoed those in the abandoned shopping mall: when they left Syria, they assumed it would be for six months but they had now been here for six years; they desperately wanted their children to have an education. If some of the adults had given up on their own futures, they were determined to find a way to get their kids out of the refugee camp.

Driving closer to the Syrian border, we parked next to a jumble of shacks with corrugated roofs. Here, the second Syrian couple who were moving to England lived with their two daughters. The two-year-old kept kissing her father’s cheek while the six-year-old bounced on his lap, vying for his attention like all kids that age do. The mother, cooking her family a lunch of rice and potatoes and apologizing that she didn’t have enough to go round, explained that they hadn’t wanted to leave their family in Syria but that they had to protect their daughters – from war and then, as they turned eleven or twelve, from being sold into sexual slavery.

I knew what the mother and father wanted for their daughters: an education and a future in a country free from war. It wasn’t much to ask and yet they knew they were the lucky ones.

Shortly after the trip to Lebanon, David Morrissey and I met up with Gary Lineker. An outspoken supporter of refugees on Twitter, he agreed to write a foreword to A Game of Two Halves and to help us get some of his Match of the Day and BT Sport colleagues on board. We agreed that there should be no more than two players or managers, past or present, from each team. I wanted the list to be as geographically diverse as possible, but the pairings were logistically challenging and the book limited in its length, so apologies to Newcastle and Sunderland fans. And Wales fans. And all the other fans whose teams aren’t represented in this book.

Between October 2017 and May 2019, twelve fans met twelve footballers. (I came off the bench to chat to the Arsenal and Netherlands star Vivianne Miedema after the brilliant poet Hollie McNish moved heaven and earth to meet Miedema at her home in St Alban’s but was finally defeated by her never-ending touring commitments.) The twists and turns of the 2018–19 Premier League season will live long in the memory – Liverpool and Tottenham’s respective routes to the Champions League final in Madrid, beating Barcelona and Ajax against all the odds, is the stuff of dreams; Manchester City winning the League by one point – and as such made it impossible to keep all the chapters up to date.

It was hard enough to get two busy people in a room once, let alone be afforded the opportunity to update their chapters. When Liverpool-born David Morrissey met Steven Gerrard, for example, Gerrard was still managing the Under-19s at Liverpool and had not yet taken on his job as manager of Rangers; when I met Miedema, she was already a superstar in her native Holland but had yet to become the all-time top scorer for the Netherlands women’s team, as she did in the second game of the World Cup. Nevermind; each chapter captures a moment in time, a revealing and sometimes surprising glimpse of the real person behind the myth.

I sat in on and moderated all the interviews except Val McDermid and John McGlynn, which took place in Kirkcaldy, Fife, and clashed with another interview in the book. It was fascinating to watch the famous fans relate to the footballers or managers they admired and vice versa. When my iPhone wasn’t recording, the shy and serious Steven Gerrard relaxed and started chatting to David Morrissey about playing golf in Liverpool and the friends they had in common. Six months before the Women’s World Cup kicked off in France and pushed the women’s game onto centre stage, Clare Balding and Lucy Bronze had a heated discussion about how women’s football needed proper, across-the-board support.

Omid Djalili arrived on his motorbike to chat to Frank Lampard at the private health club at Stamford Bridge and Lampard stayed for over two hours even though he had only promised one, while Rachel Riley cycled across London to meet Rio Ferdinand at his London Bridge offices to discuss the good old days at Manchester United. Gary Lineker – his flight from Munich delayed the morning after the Bayern v Liverpool second leg – dashed across London to meet former Syrian goalkeeper Fahd Saleh at UNHCR’s offices and then listened to Saleh’s painful story thoughtfully and solicitously.

Sometimes I felt as though I was intruding on a kind of blind-date-for-mates. The fashion-conscious Héctor Bellerín got so carried away when chatting to Romesh Ranganathan about veganism and social media that he didn’t have time to go home and get changed out of his tracksuit before going to see Ricky Gervais live. Wretch 32 and Ian Wright finished each other’s sentences and the latter then posted a photo of the two of them on Instagram above the caption, ‘It will never feel normal chilling with this legend.’

Johnny Marr was genuinely thrilled – and thrown – when Pep Guardiola asked him to sign a vinyl copy of his most recent album. Guardiola’s office at the heart of Manchester City’s Etihad campus was dominated by a white board detailing upcoming opponents. Psychology books were piled up at one end of his desk. The yellow ribbon that Guardiola sometimes pins to his jumper in support of political leaders jailed following the Catalonia independence referendum in 2017 sat next to a photo of his wife and kids. Right in front of me on the desk was a document entitled ‘Liverpool’, written in Spanish. At the end of his chat with Johnny Marr, Guardiola led us out of his office, chatting away and making jokes about this and that. Someone mentioned the fact that I was seeing Jürgen Klopp the next day and that I support Liverpool, and Guardiola took me by the arm as we stood at the top of the stairs.

‘So, tomorrow you see Jürgen! Give him a big hug from me. A big hug! Tell him to be calm. He’s a really nice guy.’

I smiled. I tried not to be partisan while working on this book, but at times it was a real challenge. There I was at the Etihad, making small talk with the only manager who could stop my team from winning the Premier League for the first time since 1989–90.

‘So,’ the hugely likeable Guardiola continued, beaming, ‘I was just the appetiser. The main dish is tomorrow with Jürgen. We are a humble team, a humble club. We built our club stone by stone, like a cathedral. Liverpool are looking at us, thinking that they’ve done it all, which of course they have.’

The next day, I passed on Guardiola’s message to Klopp, who replied: ‘OK, good. I’ll give him a hug back when I see him next time.’ Football remains an alpha sport, but this hugging business that Klopp excels at is heartening. (I later watched the six-minute video filmed after Liverpool won the Champions League, in which Klopp walks around the pitch hugging everyone, including bereft Tottenham players. It might have been a small act of humanity, but it somehow felt like a bigger gesture.)

While waiting for Klopp, John Bishop and I had a super-healthy lunch at Melwood, Liverpool’s training ground, and watched the first-team players come and go. There was James Milner asking about a secret stash of chocolate while Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain chatted about navigating his long-term injury in the most positive way possible, and Andy Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold passed through, grinning at some private joke.

I was born in London but spent school holidays in Liverpool, where my grandfather – a surgeon who occasionally operated on elite athletes – once operated on Graeme Souness and brought home autographed photos of that magnificent early-1980s Liverpool team. I spent time around the club in the mid- to late 1990s, watching Robbie Fowler, Steve McManaman and then Steven Gerrard play great football but win very little. Alongside many Liverpool fans, I feel that Klopp has a special affinity with the club, like Shankly, Paisley and Dalglish did before him. A couple of Scots, an Englishman and a German. Sounds about right to me.

When Bishop interviewed Klopp – and it was an interview more than a chat, which is just the way some of these pairings turned out – Liverpool had yet to win the Champions League and lose the League. Klopp was less laid-back than Guardiola, despite both having just returned from an international break, but he was no less attentive. Klopp was in fact so fired up by racism and politics when we went into his office (with its map of the UK on the wall so that he could see the location of away games when he first arrived from Germany) that he talked about these subjects non-stop for a third of the interview. I, for one, was happy; after all, this is why I wanted to do the book. This is what I hoped the book would be, especially when racism reared its ugly head as the season wore on and Raheem Sterling spoke out for himself and other young black players who were being unfairly maligned by the right-wing press and abused by a small number of fans.

Right at the end of the season, after Man City had won the Premier League by a single point, I asked Sterling if, having found his voice, he might consider writing a foreword to sit alongside Lineker’s. He immediately agreed and wrote it straight from the heart.

David Lammy and Eric Dier were the final pairing to meet for A Game of Two Halves. They were supposed to be one of the first, but as David Lammy and I were heading for Tottenham’s training ground in December 2018, Eric Dier was forced to cancel; he was suffering acute abdominal pain that turned out to be appendicitis. Then, with his immune system compromised, Dier got flu and cancelled again. But he finally made it to Parliament towards the end of May 2019, when both he and Lammy were still full of hope that Tottenham could win their first ever Champions League trophy.

A footballer asking a politician, unprompted, about the minimum wage and the London riots was a fitting end to a book in which there was also much levity (see Marr asking Guardiola about his apparently endless supply of round-necked cashmere jumpers). There is no denying that football is, at times, political or that it can transcend atomization. Maybe I’m being ridiculously optimistic, but through the prism of football, we can perhaps see ourselves more as a global ‘us’ than an ‘us v them’. We can stop the dehumanizing ‘othering’ encouraged by Brexit, when people who ‘aren’t like us’ are classified as ‘not being one of us’.

As twenty-four-year-old Raheem Sterling points out in his foreword, Britain is great because ‘we are diverse, we are cultured, but most importantly we are one.’ He has the first word in this book, but he should also have the last.

David: What was going through your head the first time you came onto the pitch as a first-team player?

Steven: When Phil Thompson shouted me down at the Kop end to come on for the last few minutes, it’s the one time as a footballer where I’ve been close to needing a nappy.

BT Sport, London, October 2017

David Morrissey was born in Liverpool in 1964. He joined the Everyman Theatre at sixteen and, two years later, was cast in the television series One Summer. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and spent time both at the RSC and the National Theatre. He found global stardom playing the Governor in The Walking Dead, but in Britain he is rarely off our TV screens, starring in Red Riding, The 7.39, The Missing and Britannia. His acclaimed theatre work includes In A Dark Dark House, Hangman, Macbeth and Julius Caesar. In 2007, he was awarded an Honorary Fellowship for contributions to the performing arts at Liverpool John Moores University. He volunteers for several charities, including The Felix Project and The Bike Project. He is a Goodwill Ambassador for UNHCR.

Steven Gerrard was born in Liverpool in 1980. When he was eight, following a recommendation from his local football team manager, he was fast-tracked into Liverpool’s Centre of Excellence alongside players such as Michael Owen. At sixteen, Gerrard started a two-year training course at Melwood, Liverpool’s training ground. He made his first-team debut on 29 November 1998 against Blackburn Rovers.

Although the Premier League title eluded him, he went on to win two League Cups, two FA Cups, a European Super Cup, UEFA Cup and a UEFA Champions League Cup with Liverpool. Gerrard captained both Liverpool and England, scoring twelve goals in fifty-seven appearances for his country. Aft er playing for Liverpool between the ages of eight and thirty-five. he finished his career playing for LA Galaxy in the Major League Soccer. Gerrard completed his UEFA A Licence and took his first managerial role as Liverpool youth coach, before managing the Under-18s. In June 2018, Gerrard became manager of Rangers.

David Morrissey: Let’s start at the beginning: how old were you when you realized you were different from your mates?

Steven Gerrard: Probably around the age of thirteen; I knew then that I was going to be a professional footballer because I was offered a long contract by Liverpool. A two-year schoolboy contract, a two-year apprenticeship – called the YTS back in the day – and a three-year guaranteed contract after that. I didn’t know I was going to play for Liverpool’s first team back then, but it was the age I said to myself, ‘I must be half decent…’

David: You must have known you were decent when you were knocking a ball around with your mates in the playground?

Steven: I knew I was a level above. A bit different. That sounds big-headed, but I don’t know how else to put it. I just found it really easy. Sometimes I’d play with the ball on my own in the playground because playing with kids my own age wasn’t enough of a challenge.

David: What are you earliest memories of watching football?

Steven: I lived in a street called Ironside Road on the Bluebell Estate and there were always street parties when Liverpool played Everton in a cup final. In May 1986, when I was six years of age, there was a crazy street party for the FA Cup Final. It was probably the first full game I watched.

David: I remember those parties! Are you saying that you got into football for the party?

Steven: Well, that party was certainly an eye-opener! What’s this big occasion, why are we having a street party? I obviously knew my dad and my brother were Liverpool fans, but Everton scored in the first half. A Gary Lineker goal. At which point, I was thinking of being a blue. My mum’s brother was a blue too. It was touch and go if I was going to be a blue or a red. My mum’s side was more blues, my dad’s side was strictly reds. And then obviously the game was turned around on its head in the second half and it ended up being 3-1 to Liverpool. Rushy [Ian Rush] scored a couple and Craig Johnston scored one. At the end of that day, worn out from watching the Cup Final and having enjoyed the street party, I officially became a red.

David: I had a very similar thing with my son, who grew up in north London. The first big game we watched together was Arsenal v Liverpool in 2001. I really talked up Liverpool, determined to make him a red. But when Freddie Ljunberg scored for Arsenal in the seventy-second minute, my son was really torn. He looked so guilty. And then, of course, with just ten minutes of the game left, Michael Owen scored two and Liverpool won. That was it, my son was a Liverpool fan.

Steven: It’s mad how certain moments can decide who you support.

David: How would it have gone down at home if you’d have been a blue instead?

Steven: Not very well, because my older brother is a red as well.

David: I’m from a split family too. My older brother is a blue, as was my dad. My other brother and I are both reds. It’s always tricky.

Steven: To be honest, from the age of six I’ve had a very nice time being a red because Liverpool dominated the city during that period. I think I made the right decision.

David: You absolutely did. What are your memories of being at Liverpool once you’d signed on to their YTS?

Steven: Well, for one thing, we all earned the same: £47.50 a week. I was sixteen, I’d left school and for the first time I had money in my pocket.

David: How did signing on for Liverpool go down with your mates? Did your relationship have to change?

Steven: Slightly, yes. I came from a council estate where gangs of lads used to get up to things that I couldn’t get involved in. I suppose at times I was the boring one. I had to go home early. I was sent home on many occasions by my older brother if he saw me out after a certain time. Or if he saw me around, getting up to no good, I’d normally get a kick up the backside and get sent home. So I had the right people around, telling me what to do before I got involved in the wrong stuff.

David: I assume the club looked after you too, given that you were effectively an investment for them?

Steven: I wasn’t aware of it at the time. But later I spoke to my dad and Steve Heighway [former Liverpool player who became director of Liverpool Academy] about it and Steve was regularly on the phone, asking where I was and what I was up to. He told my dad to keep me off the streets and out of trouble.

David: Were there dietary restrictions too?

Steven: It wasn’t as strict as it is now. At fourteen, young players are now told exactly what to eat. And what not to eat. Whereas we were just told to keep an eye on the fast-food side of it.

David: I presume as a trainee you were expected to do some crappy jobs?

Steven: The jobs at Melwood – there was no Academy then – were organized via a monthly rota. For example, three or four lads were in charge of making sure all the floors were clean. Another three or four would be in charge of the medical department, making sure everything was tidy and the towels were clean. Others would be on laundry duty, cleaning first-team boots or sorting out balls, bibs and cones.

David: Was it pressurized or did you have a laugh?

Steven: There was pressure in the sense that you’d have Ronnie Moran, Sammy Lee and Phil Thompson barking down your ear, telling you that you’re a lazy F-U-C-K. You had to make sure you were on it. We laughed on the job when we were sorting the balls, bibs and cones because they were kept next to the staff toilets. Most of the staff were quite regular of a morning so it used to stink in there. It could be a long month. Big Joe Corrigan always seemed to have been to the toilet ten minutes before we had to start work.

David: How much did you interact with the first team, some of whom were your heroes?

Steven: All my heroes were in the next dressing room. We used to go and watch them on a Saturday. Jamie Redknapp. Robbie Fowler. Before that, when I was a schoolboy, it was the likes of John Barnes and Ian Rush.

David: How were they with you?

Steven: Brilliant. Just great fellas.

David: Very early on in my acting career, I worked at the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool. In the company at that time were actors like Jim Broadbent and the late Pete Postlethwaite. I used to go up to them and ask about acting and they were always great. Rather than telling me to get lost or smacking me around the head, they really encouraged me. I made sure I thanked them when I was older and established.

Steven: Yeah, it’s odd because I ended up sharing a dressing room with all these players. I went from cleaning their boots, putting their kit out for them and being intimidated around them to actually playing with them. It was a big learning curve, learning how you treat people younger than you, who are striving to make it.

David: When you are training with those players and watching them win, lose or draw at the weekend, how did it feel when you turned up at Melwood on a Monday morning?

Steven: There were these benches where all the young apprentices used to stand holding a couple of balls and a couple of shirts. Your responsibility as a trainee was to wait for every first-team player to walk past and make sure they signed the shirts and balls for local charities. If they’d lost at the weekend it was a long ten to fifteen minutes because you could just see by their faces…

David: Not just as a team, but individually?

Steven: Yeah, each of them was carrying the result from the weekend. Whereas, for the majority of us, as sixteen- or seventeen-year-olds, if you lost at the weekend you mostly got over it pretty quick. That’s where football changes. It becomes less enjoyable the higher up you go simply because there’s more at stake. It’s only enjoyable when you win.

David: By the time Gérard Houllier brought you through to the first team, you must have been ready to make the transition. What was he like as a manager?

Steven: He was a father figure to me. He was always there for me. He basically changed the way I lived off the pitch. Growing up, I was quite relaxed. My diet, my social life, which nights I’d go out, where I’d go out and play with my friends. As soon as I met Gérard Houllier, my life changed off the pitch. For a start, I didn’t get home till much later because after training he had me doing extra weights.

David: To build you up?

Steven: Yes, because I was a skinny, fragile player at the age of sixteen. Between the ages of sixteen and twenty, I had to do a lot of extra work so my days were longer. Gérard also had a meeting with my parents to make sure that after I came home from Melwood, I was in and resting for the rest of the day. We got all kinds of diet information, and the fridge had to change.

David: Do you think that was to do with Houllier being French?

Steven: He certainly changed the culture of the whole club.

David: Would it be too much to say his influence reached beyond Liverpool?

Steven: I don’t think you can give him the credit for any other club, but the likes of him and Arsène Wenger – and the general influx of foreign managers at the time into the English game – changed everything. Prior to their arrival, there was a culture of drinking, overeating and eating the wrong stuff. And getting away with it. But then the foreign managers came in and changed the rules – and as a result their clubs improved and moved up the league and then everyone else tried to catch up.