18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

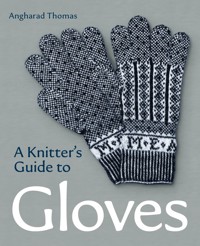

A Knitter's Guide to Gloves introduces several construction techniques, alongside the possible materials and tools that are suitable for knitting the gloves you want. A chapter on design guides you through adapting and customising your glove knitting before outlining how to go about designing from personal inspiration. The book also traces the history of knitted gloves and is lavishly illustrated with examples from museum collections, some of which are rare or even unique. Patterned gloves from Yorkshire and Scotland are described, alongside the stories of examples that have survived into the twenty-first century. Selected gloves from Estonia are discussed, as well as some from UK collections including the Glovers Collection Trust and the Knitting and Crochet Guild. Includes step-by-step photos guide those new to knitting gloves through the key points of glove construction and making your first pair. Five further glove patterns then give a choice of styles to knit, from a plain pair through to colourworked gloves of varied complexity.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Geof Cunningham

First published in 2023 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2023

© Angharad Thomas 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4173 6

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov

Dedication

To Mary Allen of Dent and Mary Forsyth of Sanquhar, glove knitters

CONTENTS

Introduction

1Understanding Glove Knitting

Pattern 1: Plain Inspired

2A History of Knitting or a History of Knitted Gloves?

Pattern 2: Inspired by History

3Patterned Gloves in Yorkshire, Scotland and Estonia

Pattern 3: Inspired by Mary Allen

Pattern 4: Inspired by Alba

Pattern 5: Boreal Inspiration

4Get Creative: Design for Glove Knitters

5Knitted Gloves in Collections

Pattern 6: Vintage Inspiration

Appendix I: Abbreviations

Appendix II: Alphabet Charts

Bibliography

Resources

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

This book is about knitted gloves. It’s a lot about knitting and it’s a lot about gloves. Both are fascinating, so together they must be even more so. Some of it is relevant for knitting of any kind. Why gloves? Why not hats or socks, as surely they are easier to knit? And can’t warm, hardwearing gloves be bought for a small amount of money almost anywhere? So why knit them?

Knitting has been a fascination of mine for most of my life, and at times also my employment. I am a hand and machine knitter, and use either as the task demands. Knitted gloves have been part of my knitting repertoire since I started to make them about forty years ago, using patterns in Patons Woolcraft, that long-lasting staple of instruction and basic patterns. At that time, because I was a knitter, a friend gave me a pair of gloves, finely hand knitted in grey and red wool, shown in the illustration, which she said had come from her aunt who kept a post office in the Yorkshire Dales. These gloves fascinated me as I had never seen knitting so fine and so patterned – and that must have been the beginning of my obsession!

Gloves – that is, hand coverings with separate fingers – have been found throughout recorded time, and making gloves, whether from fabric or skins, has continued ever since. The name for this hand covering with separate fingers is said to have various roots; however, my favourite is that the word ‘glove’ came from an old Belgic word gheloove, meaning faithfulness, as gloves have been so strongly associated with love tokens.

For me, the interest in gloves lies in the endless variations: as protection from cold or hazards, as decoration or status symbol, as part of a uniform, as part of sports kit – all these are possibilities for the glove. A glove can be the most exquisite work of craft and skill decorated with precious metals and jewels, or it can be see-through plastic of the sort that is given out at the petrol station or with hair dye, or to protect the hand from contamination during a pandemic. Gloves might be worn to protect the hands from irreparable damage in severe climates, or they might be of diaphanous lace covering the hands and arms, the only intention being decoration. Given the many uses to which a glove or gloves can be put, the many materials that gloves can be made from, and the differing resources that may be used in glove manufacture, this variety is probably infinite.

Religious writings, myths, legends, the Greeks and Romans, not to mention Shakespeare, all refer to gloves. Shakespeare was close to gloves, being the son of a glove maker, whose workshop can be seen in his home town of Stratford-upon-Avon, England. It would be natural to him to be familiar with the ‘language’ of gloves. In the other contexts, from earliest times, gloves are given as tokens of affection, they are passed around with money in them, they are worn on hats as a signal of loyalty, and they are perfumed and given as gifts. They may or may not be worn, depending on particular circumstances. Judges wore white gloves when there were no instances of the death penalty in that session of the court, and there was a period when Wales was known as the ‘land of white gloves’. Gloves were apparently given as gifts to attendees of weddings and funerals.

These customs are recorded and found all over Europe, and were actively used or performed until relatively recently. Some associations still continue in modern form, such as the contemporary furniture removal firm that reassures prospective customers with its title of ‘White Glove Removals’, indicating the level of care that will be taken.

References to gloves permeate our speech, from phrases such as ‘hand in glove’, ‘throwing down the gauntlet’, ‘quirk’ (a small piece of a leather glove that enables the finger to fit well), ‘fit like a glove’, and ‘the gloves are off’.

Despite the warming climate, our sedentary indoor lifestyles, central heating, use of the car and so on, gloves are still part of daily life, whether it’s for doing the washing up, for gardening, or when going out for a brisk, life-enhancing walk in nature! That’s where a pair of cosy hand-knitted gloves might come in handy! (Absolutely no pun intended!)

I hope this book conveys to you, the reader, just a fraction of the interest and excitement I have had from making, designing and studying knitted gloves, this extremely niche textile activity.

CHAPTER 1

UNDERSTANDING GLOVE KNITTING

Background: Why Gloves?

The Significance of Gloves

Gloves come in a vast range of types, either functional or decorative, or both in some cases. Gloves can protect the hands from dirt or germs, can insulate them from extreme temperatures, whether high or low, or give protection from danger in a work context and on the sportsfield. From delicate lace gloves, which can be knitted or crocheted, to embroidered gloves made from the finest materials for ceremonial occasions, or elbow-length evening gloves or chic leather gloves for driving, the whole spectrum of style is to be found. Gloves have a place in the English language too. We use phrases such as ‘hand in glove’, ‘fits like a glove’ or ‘taking the gloves off’ to add weight and colour to our meanings. Gloves have been used over the centuries as tokens of power or love, and later in this book examples of gloves used in these ways are shown.

The oldest pair of gloves in existence are those that were discovered in the tomb of the Egyptian king Tutankhamun, dating back over 3,000 years. It must be emphasized, however, that these were not knitted. Chapter 2 gives an outline of the history of the glove as an item of clothing, where it will be seen that the knitted form appears quite late on.

Gloves Expressing Feelings – Exploring Relationships

Perhaps because of the immense possibility of variation in the glove form, briefly discussed above, and because of its close relationship with the human hand, gloves have been used in both fine art and craft contexts to explore specific questions or feelings by makers in recent years. British artists Rozanne Hawksley and Alice Kettle have employed gloves to great effect in their textile pieces during their careers.

Rozanne Hawksley has used gloves in her constructed textile works over a period of many years, and the importance of the glove in her work as a symbol and motif is reflected by its presence in the Glove Collection Trust, the collection that has its origins in the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London. Five of Rozanne Hawksley’s pieces that feature gloves are to be seen as part of this collection on its website (seeResources section at the back of this book). All use the glove form, three with a large, flared gauntlet, heavily ornamented and decorated, in the way that gloves were constructed historically, and two using the form of long, white, formal gloves as the basis for the artwork. However, the message of power and status is then subverted by additions such as Tarot cards, small animal skulls, and inscribed ribbon saying things such as ‘famine’.

These pieces, which are labelled as ‘Sculpture or assembled artwork’, use the language of gloves to convey powerful messages, commenting on life, death, and the human condition. Other pieces use large numbers of gloves in wreath shapes to give messages about the futility of war and the need for peace. Some of these are in the collection of the Imperial War Museum, London. In a book about Rozanne’s work Mary Schoeser says that ‘for a number of years [she has been] using the glove as the symbol of the human individual’ – and Rozanne’s work shows this to be a rich seam of visual imagery.

The attraction of gloves is explained by Alice Kettle in her artist’s statement for her exhibition ‘Telling Fortunes’ in Platt Hall Gallery of Costume, Manchester, UK in 2010. She says:

I am amongst many artists who are drawn to gloves. Loaded with the symbolism of touch and the haptic they are suggestive of the movement and gesture of the hand. They carry a sense of changing cultural attitude, when gloves must be worn, of the untouched and must not touch, and of relationships, when hands are to be held. They hold within their interior a sense of the hand within.

Using gloves from the collection held at Platt Hall, her embroidered piece ‘Glove Field’ outlines many gloves filling a white cotton background that measures 1 × 2m. A central structure in the exhibition had gloves from the Platt Hall collection displayed on it, and other visuals used the outline of the glove as a motif, including on ceramic pieces. These works can be seen on Alice’s website (seeResources at the back of this book).

Freddie Robins has used the knitted glove form to explore ideas, responding to them in a playful way. Dating from 1997, the series of four knitted gloves shown comment on the form of the hand itself, reacting to and exploring related issues. ‘Polly’, second from the left, is a comment on the polydactyl condition, when a person may have more than five fingers, while ‘Conrad’, to the right of it, imagines the consequences of thumb sucking in a German fairytale, which results in the boy’s thumb falling off.

‘Giles’, ‘Polly’, ‘Conrad’, ‘Peggy’, from the series ‘Odd Gloves’, 1997. Machine-knitted wool, mohair. Approximately 240 × 160mm. ‘Giles’, ‘Polly’ and ‘Conrad’ are in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; ‘Peggy’ is in a private collection. (Ben Coode-Adams)

Subsequently Robins has knitted gloves that are joined to each other in pairs that would never come apart, some that have small gloves at the tips of the fingers of a larger glove, and some that are joined at the cuffs in a cross form. One series, the ‘Hands of Hoxton’, commissioned by the London Borough of Shoreditch, matches the gloves to well-known figures from the local area, and this can be seen on the Freddie Robins website (seeResources). One of Robins’ stated aims with these impossible-to-wear gloves was to get away from the idea that everything ‘has to be useful’, especially for female makers, for whom this is an additional constraint to female creativity.

Types of Hand Covering

The German and Dutch words for glove translate as ‘hand shoes’ – in other words, a shoe for the hand, and this is what a glove is, in effect. It is a protection or decoration for the hand, in the way that a shoe is for the foot. Passages in the Bible have been thought to refer incorrectly to ‘shoes’ when they should have referred to ‘gloves’, so it seems that the connection is close in other languages too. A common definition of ‘glove’ is a covering for the hand worn for protection against cold or dirt, and typically having separate parts for each finger and the thumb. The forms that hand coverings take can vary widely from, at the simplest, a rectangle of fabric folded in half and sewn up with a gap for the thumb, to a full glove with a gauntlet coming over the wrist; see the circular illustration of some of these varieties.

Types of hand covering.

The focus of this book is gloves with full fingers, but any glove pattern can be amended simply by finishing at the level of the knuckles for a fingerless mitt, or turning it into a mitten without separate fingers. Just the cuff and wrist could be made to produce wrist or pulse warmers. For using touch-screen phones and tablets, having finger ends accessible can be an advantage in all but the coldest weather. Gloves are on the market with touch-sensitive areas at the fingertips for use with screens, and conductive thread can be bought for making additions to existing gloves. For artists using screens, gloves consisting of the third and fourth fingers only, which leave the first and second fingers free, are now available, giving yet another permutation of hand covering.

So, with reference to the forms shown, the simplest of these is the wrist warmer, pulse warmer or muffatee, which covers just the wrist area (A). Then the simplest hand warmer is just a tube with a slit for the thumb (B). The form progresses to having a shaped section for the thumb with a separate opening, fingerless mitts (C). Mittens enclose the fingers but keep the thumb separate (D), while a shooting glove or trigger glove has a single finger and a larger space for the other three fingers of the hand (E). Fingerless mitts can be made with a pop-over top allowing some flexibility in use (F), while a fingerless glove has fingers that usually end at the first knuckle (G). A full glove covers the hand while keeping the fingers and thumb separate from each other (H). A glove with a gauntlet comes down over the wrist and part-way up the arm (I). Elbow-length gloves are just as they are described (J).

All these shapes and constructions are related and are relatively easily varied by the maker. For instance, a glove pattern could be used to make most of the variations shown, a possible exception being B, a wrist warmer that is best made from a flat piece of fabric, so that an opening can be left for the thumb, while all the others are easier to make by knitting in the round. All the patterns in this book could be turned into wrist warmers or mittens or fingerless gloves, as preferred. Making adaptations such as this is discussed in Chapter 4. This book takes the full finger glove, H, as its standard model, and all the patterns are for this form of hand covering; however, from this basic shape, the other variations are easily made.

The Anatomy of a Glove

Gloves have particular names for the various parts, these being simplified from the intricate constructions of fabric or leather gloves. Knitted gloves are less complex in their construction as the fabric is stretchy and so accommodates the hand more easily; this is one of the main advantages of using knitting as a glove-making technique. The ‘anatomy’ of a typical knitted glove is illustrated.

Anatomy of a glove.

Construction usually starts (but does not have to) at the cuff, which, if hand knitted, is often ribbed for a snug fit. Above this, the wrist can be patterned or textured. The shaping to accommodate the thumb, the thumb gusset, then takes shape. In a shaped or gusset thumb, once the stitches for the thumb are formed, they are either taken off and saved to be knitted later, or they can be knitted immediately. Another option is for the thumb to be constructed from a simple slit in the palm of the glove, from which the thumb is knitted up. This is called a peasant thumb. Above this, the hand can again be patterned.

The fourth finger is often knitted first. After it is completed, the hand stitches are returned to and knitted to form the hand extension. This is to take into account the fact that for most people’s hands, the start of the fourth or little finger is lower than the others. Note for anxious glove knitters, this is not essential! Knitted gloves have enough stretch and accommodation to allow for this without the hand extension, although it is a nice refinement for ensuring a good fit.

The fingers are formed in turn by taking stitches from either side of the hand and making extra stitches by both casting on and picking up and knitting, to allow for the width of the hands. These stitches can make fully formed finger gussets or fourchettes, or just be a group of several stitches. The fingers are knitted in turn, individually, with the fingertips then shaped to either a blunt or pointed end.

A Little More about Thumb Constructions

The hand of a glove is a cylinder of fabric that wraps around it, but the thumb has to go somewhere and gloves must be constructed to allow for this. It can be done in several ways, and this can be confusing for the beginner glove knitter. However, after having knitted a pair, things should become clearer.

The Position of the Thumb

On the side of the hand: The thumb shaping is positioned between the stitches for the back and the front of the hands, where they meet. Its position on the side of the hand means that both gloves are identical and can be worn on either hand.

Alternatively:

On the palm of the hand: The thumb shaping is positioned on the palm of the hand, bringing it round to the front of the hand a short way, perhaps a few stitches. This means that the right and left glove are different from each other.

Side thumb, symmetrical.

Peasant thumb, on palm.

Thumb on palm, symmetrical, showing increases.

Thumb on palm, symmetrical, showing increases.

Thumb on palm, asymmetrical, showing increases.

Thumb on palm, asymmetrical, showing no increases.

The Construction of the Thumb

How the thumb is shaped and constructed also varies, some methods increasing in the hand to form extra space for the thumb by means of a thumb gusset, or by making a slit in the fabric through which the thumb will fit.

A symmetrical gusset thumb works the increases for the thumb gusset at both sides of it, forming a symmetrical shape.

A symmetrical gusset thumb that is placed to the palm side of the hand is used in many published patterns. It means that the right and left hands are different.

An asymmetrical thumb has all the increases on one side of the thumb gusset. It, too, can be placed at the side of the hand or on the palm.

A peasant thumb is the simplest, and is made by making a slit on the palm side of the hand, usually by knitting some stiches with spare yarn, and then returning to them, taking out the spare yarn and knitting the resulting loops into the thumb. It’s simpler than it sounds! This method is used in Pattern 5: ‘Boreal Inspired’ (Chapter 3).

The following thumb constructions are used in the patterns in this book:

•Chapter 1: Pattern 1, ‘Plain Inspired’, has a symmetrical thumb gusset placed at the side of the hand.

•Chapter 2: Pattern 2, ‘Inspired by History’, has an asymmetrical thumb gusset placed on the palm of the hand.

• Chapter 3:

Pattern 3, ‘Inspired by Mary Allen’, has a symmetrical gusset placed towards the palm of the hand.

Pattern 4, ‘Inspired by Alba’, has a symmetrical thumb gusset placed at the side of the hand.

Pattern 5, ‘Boreal Inspiration’, has a peasant thumb on the palm of the hand.

•Chapter 5: Pattern 6, ‘Vintage Inspiration’, has an asymmetrical gusset placed on the palm of the hand.

The variety of thumbs gives the knitter the opportunity of making different ones.

Note: For these thumbs, once the stitches are back on the needles from the thumb gusset or slit, the thumb itself is most often just a tube until the shaping for the tip is reached. Occasionally there might be a little decreasing at the base of the thumb to bring down the stitch count, and this is found in Pattern 1, ‘Plain Inspired’, in Chapter 1.

Direction of Knitting

In fact, gloves do not have to be knitted from the cuff edge upwards. There are examples of gloves being knitted from the fingertips downwards – for example, the glove that is known as the glove of St Adalbert, in the treasury of St Vitus Cathedral, Prague, from the fourteenth century, as documented by Sylvie Odstrčilová in her article in ‘Piecework’, and in the present day, when gloves knitted in Nepal have been shown to be knitted in this way.

Gloves can also be knitted sideways, and an example of such a glove is shown in Chapter 5. Elizabeth Zimmermann gives a pattern for gloves that are hand knitted sideways in garter stitch in Knit One, Knit All, her book of garter-stitch garments from 2011. Patterns were also written for gloves made sideways on a knitting machine in the 1950s. The main disadvantage of this way of constructing a glove is, of course, the amount of sewing up to be done, whether that is actually sewing seams up the fingers, or joining stitches by grafting them together (Kitchener stitch).

Knitting Gloves

Gloves are fascinating to knit. They can challenge experienced knitters and use specific techniques in their construction. A small project, taking a small amount of yarn, gloves can be knitted with yarn from a stash. Whether on double-pointed or circular needles, they pack up small and are portable.

For the knitter new to gloves, it is strongly recommended that a plain pair is knitted first, tempting though it might be to launch into a patterned pair from the later chapters in this book. There are several specific operations and techniques to be undertaken in constructing a glove, and these are easier to manage with one yarn, rather than two. Having knitted a plain pair, the knitter is then equipped to knit more complex patterns, as well as being more confident to make their own modifications and additions. Knitting a plain pair gives an opportunity to try out new yarns and needles, and to understand the process of construction. It also gives the knitter the opportunity to check the fit, whoever the gloves are for. And if they don’t fit the intended recipient, another one can soon be found.

So, where to start? It’s likely that most knitters will have everything that is needed to make a pair of gloves, so let’s have a look at what this might be.

Yarns for Glove Knitting

Of course, gloves can be knitted in any type of fibre and yarn, and a selection is shown. Wool, cotton, silk or synthetic yarns can all be used, depending on what is wanted. The most esoteric fibre ever used to knit gloves might be the sea silk (made from the long, silky filaments from a type of clam) found in a pair of gloves made in Italy in the late nineteenth century: an example is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession number T.15-1926 (seeResources). High-tech fibres such as Kevlar are used to make protective gloves for people who use sharp equipment in their work, such as butchers or tree surgeons.

Yarns from various fibres, left to right: alpaca, cotton, cashmere, silk, synthetic, wool.

Each fibre has its own advantages and disadvantages, of course. Wool keeps hands warm, cotton has no warmth but is decorative, and silk looks wonderful, is warm and strong, but has no stretch. Other fibres, and all the synthetic yarns or mixes of these, could also be used, according to personal preference, availability and budget. So, let’s look at some of these in turn.

Wool and Its Relations

Sheep’s wool, alpaca, mohair, cashmere and blends of these are all suitable for gloves as they are warm and have varying amounts of stretch. Shown from left to right are various wools from a pure wool 5-ply, superwash Merino, a mohair/Wensleydale blend, mohair/silk blend, angora/wool, wool/baby camel, and wool/linen/yak: they are all animal-protein fibres, except for the linen. Sheep’s wool can retain warmth even when wet and so is really second to none for gloves for proper outdoor wear, especially in wet and cold places such as Britain. Wool stays warm even when it has nearly 30 per cent by weight of water in it, and in fact a warming process is set in place as hydrogen bonds break down in the moisture. This accounts for the distinctive smell of wet wool.

A selection of wools, left to right: pure wool 5-ply, Superwash Merino, mohair/Wensleydale blend, mohair/silk blend, angora/wool, wool/baby camel, wool/linen/yak.

Alpaca or its mixes wears well and is also warm. Cashmere would make very luxurious gloves, warm and soft, but might not wear so well. Mohair, confusingly from the angora goat, is not often found in the type of yarn fine enough for gloves, although as a blend it adds strength and lustre to a sheep’s wool. Angora, from the rabbit, might be used for cuffs but could be unsuitable for the whole glove because of the fluff and surplus fibres it produces. Camel and yak fibre can be found in blends with wools and silks to make interesting yarns from specialist suppliers: some examples are illustrated.

But especially if this is going to be a first pair of gloves, and if they are wanted for warmth, then sheep’s wool is probably the fibre of first choice. There are many types of wool and thicknesses, but how it feels (its ‘handle’) and how it wears are going to be big factors in deciding what to use. So, if the gloves can be ‘kept for best’, then something soft and expensive might work, such as cashmere or even qiviut, the rare and very expensive fibre from the muskox. If just a single skein is needed this might be the project for some indulgence.

Merino and lambswool are soft, but, like cashmere, don’t wear especially well. There are pure wools from British sheep that stand up to wear better, and one of these may be a good choice.

Sheep Breeds

The British Isles has many breeds of sheep, many of which have their own recognizable fleece and wool. The study of these is the stuff of a book in its own right. Using a pure wool breed yarn can be satisfying and is completely possible with so much of this type of yarn being produced in both the UK and around the world. Most of these pure-breed wools are produced by the artisan yarn sector, who, with access to mini mill spinning, can make yarns that are specific to their flocks. In a mini mill the processing can be managed so that the fibre from a particular flock can be processed on its own, enabling it to be identified as coming from a particular source. The availability of facilities such as this is obviously crucial for the existence of a specialist yarn industry.

The wool fairs that are held in the UK and elsewhere are good places to find these yarns, sometimes being shown with the animals that supplied the fibre. Or they might be bought when visiting a flock or farm, in which case gloves knitted from the yarn would make a nice souvenir.

Pure sheep-breed wools, left to right: Blue-Faced Leicester, dyed Gotland, dyed Jacob, dyed Rambouillet, natural Shetland, dyed Wensleydale.

Blends and Mixtures

This control over the fibre content of yarn means that innovative blends of different wools and fibres can be made, giving the contemporary knitter a huge variety of yarns. Some small batch yarns may use wool from two, three or four different breeds to capture the handle or colour of each wool. This of course makes a very individual and special yarn. Many blends combine a synthetic, usually polyamide (nylon), with wool to produce a hard-wearing yarn. The 75 per cent wool with 25 per cent polyamide blend in a 4-ply or fingering weight is a classic sock wool and one that would be entirely suitable for gloves. Such yarns are very often dyed so that they make stripes and patterns as they are knitted. Self-striping yarns can be fun to knit, and will cover any irregularities in a first pair of gloves! An example is illustrated in Chapter 4.

Artisan yarns, left to right: 100 per cent wool, hand-dyed Merino wool, organic pure wool, hand-dyed sock yarn (75 per cent wool, 25 per cent polyamide).

Yarn that is artisan dyed in small batches is also a good possibility for a pair of gloves, with the provisos outlined above about handle and wear. These are frequently dyed randomly or with pronounced colour variations, which could be attractive when knitted into gloves.

Hand-Spun Yarn

If you are a hand spinner, or are lucky enough to be given hand-spun wool yarn or to be able to buy it, then this can make lovely gloves. To be hard wearing it needs to be fairly firmly spun, but it will be very warm. A yarn with a slight unevenness in it can be attractive and will hide any lumps and bumps in the knitting too, as will yarns with a marl or a fleck in them. Gloves in hand-spun wool are fabulously cosy.

Vintage Yarns

Vintage yarns, mainly wools, can be extremely useful for glove knitting when a fine, strong, smooth yarn is required, in particular for gloves with small geometric patterns such as those found in Sanquhar gloves, discussed in Chapter 3. Fortunately these can be found in on-line sales sites and are usually not too expensive. Some are strengthened with a proportion of polyamide (nylon) as they were intended for sock knitting; this makes them ideal for gloves, an example being the Regia on the left of the illustration.

Vintage yarns, left to right: Regia 3-ply (75 per cent wool, 25 per cent polyamide), Jaeger 3-ply pure wool, Patons Purple Heather, wool.

Type of Yarn and How it is Spun

A further consideration when choosing a yarn for knitting gloves is the spin of the yarn – that is, is it woollen spun or worsted spun? In the illustration the woollen spun yarn is on the left, while the worsted is on the right. This distinction can apply to yarns of any fibre, as it depends on how the fibres are treated prior to spinning. Basically, if the yarn is soft and quite open, with the fibres separated from each other, it is woollen spun; if it is smooth and not fluffy, with the fibres lying closer and parallel to each other, it is worsted spun. This is not a technical description, by the way! Some of the glove patterns that come later in this book use woollen-spun yarns, while in others, where a crisper definition of the stitch pattern is wanted, a smoother, pure wool, worsted spun yarn is more suitable.

Woollen and worsted spun yarns, left: woollen spun; right: worsted spun.

Finding Out More about Wool and Woollen and Worsted Spinning

There is a lot of information about yarn production on the internet. The Blacker Yarn Company has information about fibre and spinning:https://www.blackeryarns.co.uk/advice-information/all-about-yarn/

and the Brooklyn Tweed pages about woollen and worsted spinning are also informative: https://brooklyntweed.com/pages/woolen-and-worsted-yarn

The videos of yarn production are especially fascinating!

Needles for Knitting Gloves

Gloves, when made by hand, are best knitted in the round. Knitting gloves flat entails a lot of seaming up the hands and for each finger and thumb. The patterns in this book are constructed in the round and are small enough projects to be a starter project if this has not been done before. For those who insist on knitting gloves on two needles there are patterns out there on the internet! For circular knitting a variety of knitting needles can be used.

Knitting needles suitable for knitting gloves.

Double-Pointed Needles (dpns)

Until the knitting revival of the twenty-first century, double-pointed needles (dpns) were almost the only way to knit in the round, and they are still widely used by many knitters. Double-pointed needles have the advantage of being relatively cheap to buy, and many knitters have a selection passed on from older family members. The image shows dpns in aluminium, carbon fibre, bamboo, wood and steel, left to right. Vintage double-pointed needles are most often metal, coated aluminium or steel, and sometimes plastic. More recently, however, they have been produced in wood, bamboo or carbon fibre. If you like to knit with double-pointed needles you are spoilt for choice. Bamboo needles are good for a beginner knitter in the round as the finish is not too smooth and the yarn has some grip on their surface. They are also light and so tend to stay in place (not tending to slide out of the stitches) better than heavier metal needles.

Double-pointed needles, old and new.

Look at the ends of the needles: are they pointed or blunt? Given the option, for gloves, choose pointed ones every time to give the precision for picking up stitches and other operations while knitting gloves.

As for length, that is personal choice. For a ‘put the needle under the arm’ knitter, then the longest double-pointed needles would clearly suit, although they are perhaps a bit unwieldy for a small item such as a glove. Long – that is, 34cm (13.5in) – dpns are available on the internet.

If buying new double-pointed needles, they are usually available in 20cm (8in), 15cm (6in) and 10cm (4in) lengths. The longer length gives more flexible use for larger projects such as hats, while the shorter ones are more convenient for the fingers and thumbs of gloves.

How many needles to use?