Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

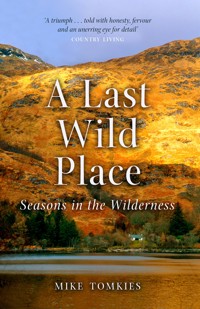

When Mike Tomkies moved to a remote cottage on the shores of Loch Shiel in the West Highlands of Scotland, he found a place which was to provide him with the most profound wilderness experience of his life. Accessible only by boat, the cottage he renamed 'Wildernesse' was to be his home for many years, which he shared with his beloved German Shepherd, Moobli. Centred on different landscape elements – loch, woodlands and mountains – Tomkies describes the whole cycle of nature through the seasons in a harsh and testing environment of unrivalled beauty. Vivid colours and sounds fill the pages – exotic wild orchids, the roar of rutting stags, the territorial movements of foxes, otters and badgers, an oak tree being torn apart by hurricane-force gales. Nothing escapes his penetrating eye. His extraordinary insights into the wildlife that shared his otherwise empty territory were not gained without perseverance in the face of perilous hazards, and the difficulties and challenges of life in the wilderness are a key part of this remarkable book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 580

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

After a successful career in journalism, Mike Tomkies returned to his childhood love of nature and spent over thirty years living in remote places in the Scottish Highlands, Canada and Spain. During this time, he wrote a number of best-selling books, including Alone in the Wilderness, A Last Wild Place, Out of the Wild, On Wing and Wild Water, Wildcat Haven and Moobli. He died in 2016.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2021under license from Whittles Publishing byBirlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN: 978 1 78027 703 5ePUB ISBN: 978 1 78885 449 8

Copyright © The estate of Mike TomkiesIntroduction copyright © Jim Crumley 2017First published in 1984 by Jonathan Cape

Subsequently published by Whittles Publishing, Dunbeath in 2017

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Typeset by Hewer Text UK, EdinburghPrinted and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Introduction by Jim Crumley

PART ONE

1 Into the Wild

2 First Wildlife Adventures

PART TWO

3 A Bird Table Theatre

4 Drama among the Birds

5 A Pup Called Moobli

PART THREE

6 The Loch in Winter

7 The Loch Gull Colony

8 The Loch in Spring

9 The Loch in Summer

10 The Magnificent Divers

PART FOUR

11 The Woodlands in Summer

12 The Woodlands in Autumn

13 The Woodlands in Winter

14 The Woodlands in Spring

15 The Red Squirrels

PART FIVE

16 The Mountains in Spring

17 The Mountains in Summer

18 The Mountains in Autumn

19 The Mountains in Winter

20 Winter of the Deer

PART SIX

21 Renewal

Introduction

With the publication of the first edition of A Last Wild Place in 1984, Mike Tomkies had finally found his feet in the West Highlands of Scotland, and found his nature writer’s voice. His earlier Scottish books, Between Earth and Paradise and Golden Eagle Years, seem in retrospect to have had the air of a work in progress, rather than the finished article.

At the heart of A Last Wild Place are fifteen chapters centred on the loch, woodlands, and mountains that surrounded the isolated cottage he called Wildernesse, each landscape element portrayed and examined through all the seasons of the year.

‘Over the years,’ he wrote, ‘I have learned it is upon these stages, through the pageantry of all four seasons, the interplay of day and night, that nature plays all the mysteries, dramas, comedies and tragedies of creation itself. Often I go, admission free, a humbled audience of one, to watch and wonder.’

In A Last Wild Place, Mike Tomkies took the reader into his confidence in a way that no-one else had done before. Seton Gordon, for example, unarguably the most significant of his predecessors among what he called ‘the high and lonely places’, was a naturalist and writer of great gifts, but there was a quality of aloof restraint about his writing. In contrast, Mike Tomkies wanted his readers to engage with him, and they did, in their thousands. His way was to show them not just what this looks like and sounds like, but what it feels like to be here on this mountain at this moment. He also ensured that they knew what it takes to produce such work, the sheer physical slog that underpinned a quite extraordinary dedication to fieldwork in such a landscape.

I had first met him in 1982 when I was a newspaper journalist on the Edinburgh Evening News and interviewed him when he was promoting Golden Eagle Years. I subsequently visited him at Wildernesse, and over the ensuing years we became good friends. But it was when I helped him on treks to eagle eyries that I gained a healthy respect for what he was trying to do there.

When A Last Wild Place appeared, I reviewed it for the Edinburgh Evening News. If you were to take my original copy down from my bookshelves none too carefully, a piece of paper would fall out. It’s a neat and flawlessly typed half-page letter from Mike, thanking me for the review and my understanding of his work, and wishing me well in my declared intentions to give up my staff job and become a nature writer.

Re-reading the book now, more than thirty years after I did just that, I remember the impact it made on me, and its author’s generosity and encouragement in the face of my own early struggles. But I am just one of many, many people who owe a debt of gratitude to Mike’s work, to his work ethic, and to this book in particular. The example it sets for its uncompromising pursuit of nature’s secrets is a lesson thoughtfully taught and well-learned. It remained his own favourite of all his books throughout his writing life, and I am delighted that it lives on in this new edition.

The final chapter of A Last Wild Place is titled ‘Renewal’. Mike writes:

In nature’s teeming world the animals and birds are working hard to fulfil their destinies. The feeling came strongly upon me that we, who evolved from original creation to become the dominant species . . . have an inherent and inescapable duty to act as responsible custodians of the whole inspiring natural world. We are the late-comers, it can only be ours on trust.

. . . If we fail to learn from the last wild places, we may yet create a hell on earth before we too pass along the road to extinction, the fate of all dominant species before us . . . The lessons will not wait for ever to be learned.

It was true in 1984. It is surely even truer today as our planet warms and our climate lurches into chaos.

When Mike Tomkies died in October 2016, nature mourned the loss of a friend and an ambassador to its cause.

Jim CrumleyStirling, 2017

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Into the Wild

The old stone cottage was cold and cheerless. As I shivered on a fish box in its empty dampness for the first time, surrounded by the debris of my former life, I felt a sudden panic. Soaked to the skin, I was fatigued after a long day ferrying boat loads of lumber and belongings up the steely grey loch under the onslaught of heavy rain. Now, my cherished hope that after seven years of wilderness living, first on a remote coast in western Canada and then in an old wooden croft on the Atlantic edge of a Scottish island, this new place would be my base for the deepest wilderness experiences of all, seemed not only presumptuous but foolhardy. No one had lived here, all year round, since 1912. When the old steamer that had once plied the loch was removed, so had died the human life along its shores.

Wildernesse, the name I had already given to the old cottage and the two small woods that flanked it, stood below a deep cleft in the Inverness-shire mountains in one of the largest uninhabited areas left in the British Isles. It was the only surviving dwelling in fifteen miles of roadless loch shore, and while I was used to isolation it would clearly be the wildest, loneliest place in which I had ever lived.

As I had found out on camping treks before leasing it, behind my new home lay a sixty-square-mile trackless wilderness of misty valleys and rivers, wooded ravines and gorges; and the first 500-foot ridges that rose steeply behind the cottage were merely the start of a succession of jagged granite outcrops and rolling hills that plunged into deep glens and led to a range of mountains whose peaks, snow-capped much of the year, towered to almost 3,000 feet.

Up there, somewhere, roamed herds of wild red deer whose stags, roaring in the autumn rut, would soon be dominating the landscape; a kingdom where golden eagles soared the skies, sharing their mountain domain with buzzards, ravens, kestrels and ptarmigan; where wildcats had their dens in rocky cairns, and at night badgers plodded from their setts, and the hill foxes roamed for miles. Across the loch to the south lay an area just as wild but three times the size.

Now, although my new domain had seemed a potential wild paradise at first view, the actual day of the move had shown me it might turn out the very opposite.

My doubts had begun at dawn when I had woken to find that two weeks of sunny mid-September skies had given way overnight to wintry darkness and drizzle, so the last boat trip from the sea island that had been my home for nearly four years had made the wrench of leaving a doubly miserable affair. No sooner had I manhandled the 500 lb weight of my new 15-foot 6-inch boat down over some pine branches into the fresh water loch that was to be my new home water and loaded it to the gunwales, than the weather worsened. The drizzle turned to sheets of cascading rain, the wind increased and as I steered fearfully through the rolling waves the long miles to Wildernesse it seemed as if the new loch was determined to make me pay a high price for moving into its world.

For the rest of the day I and my island friend Iain MacLellan, who had been given a one-day-only permission to drive my heaviest gear and old boat on a coal lorry to a private track on the loch’s south shore for the move, laboured to ferry everything across in sousing rain. We carried up more than fifty loads, struggling together with an old calor gas fridge, a mahogany desk, lumber and a heavy twenty-foot wooden scaffold device I had invented for roof repairs. At last, as dusk approached, we faced each other, totally drenched, our forelocks dangling like rats’ tails, and Iain bade me a cheerful goodbye.

‘Well, ‘tis yourself for the hardy life now. Sooner you than me!’

Alone again, as I heaved more gear out of the rain, I was acutely aware that my nearest neighbour lived over six miles away to the west. From now on my only link with the outside world, through the winter storms ahead, would be my small boat. Just to get mail (the post office had told me not even telegrams could be delivered) or supplies I could not grow for myself, I faced a thirteen-mile return boat trip, to where I parked the Land Rover in a small pine wood. Or else a long hike with hefty backpack over rock-filled bogs, high ledges, fallen trees in the long steep woodlands, and through snagging bracken, slushy peat and areas of ankle-wrenching tussocks whose flowing grassy heads hid the gullies between them.

To camp out alone in the wilds for a few days or to spend a summer holiday in such isolation was one thing, but now I faced the rest of my life, all the year round, in this lonely spot. No electricity, phone, TV, piped gas, not even a road.

A kind of madness, it would seem to many, but I had long since come to terms with my penchant for the last wild places. Initially, after years of journalism in many of the leading cities of Europe and America, I had fled to the strangeness of British Columbia to write the Great Novel. The book had failed but in those Pacific coastal wilds a city hedonism had been exorcised, the love of nature that I had discovered as a boy in Sussex had been reborn, and finally I had trekked into the last remote fastnesses to watch grizzly bears, cougars, bald eagles and caribou in the wild. Then I had become bewitched by a desire to try and also live a wilderness life back in Britain. Perhaps obeying some deep ancestral calling – for my mother had been a Highlander – I had indeed found it on the sea island of Shona, off the Inverness-shire coast. There, learning to live partly from the land and sea, had come my first close experiences with creatures like red deer, foxes, wildcats, sparrowhawks, herons, sea birds and seals. Yet those years served only to whet my appetite and now my love for the wildlife of the Highlands, still one of Europe’s finest wild regions, had all the cravings of an unconsummated love affair.

Although my earlier romantic notions about nature had long been knocked out of me, I had become consumed by a passion to sink myself totally into one of Britain’s last wild places, to live simply, close to the vital animal state myself the full year round in an even wilder place of higher mountains, longer rivers and larger forests, amid greater remoteness, this time in a fresh water environment. Only then, I felt, by more persistent study, could I possibly understand the vast interplay of Highland nature, from strand of moss to massive oak, from tiny beetle and little wren to mighty stag and golden eagle, and perhaps communicate through my writings not only love for wildlife but the necessity of conserving, even enhancing, the inspiring natural world, for the sake of man himself. To communicate my own conviction that unless man redeems the heedless greed that has destroyed so much of that world he may yet destroy the very environment he needs for both physical and spiritual sustenance, and that he, once the brightest light of evolution, will end up its greatest failure.

Pretentious aims they were, of course, but there was adventure in it all too, and I confess that after a travelling varied life, nothing else now seemed more worthwhile than to pass on what most captivated my own heart and spirit.

Well, I thought as I sank a needed dram and wiped my dripping hair with a towel, now I have the chance – if I survive!

I looked around. Twenty-four sacks of belongings lay in defeated attitudes against each other on the stone floors. Old friends of books with sodden covers seemed to stare up at me with reproach for subjecting them to even greater hardship in their old age. The mahogany desk given to me by Shona’s owners was in its future place in the fourteen-foot-square western room that was to be my study. From its window I could still see in the gathering dark a gleaming panorama of four miles of turbulent loch before it vanished in a bend between the hills – merely the last leg of the day’s hard drenching journeys. In the kitchen of similar dimensions that lay at the other end of the cottage beyond a small bedroom, the heavy old calor gas fridge, the first preserver of provisions I had owned in seven wilderness years, stood against a cold stone wall. Outside the wooden scaffold rested on the roof, ready for its repairs. At least the heaviest items were in place.

Wearily I went out into the rain again and down the muddy forty-yard path to the shore and brought up two more loads. Then my body gave out. Too tired to peel vegetables, I warmed up a tin of soup, spooned it down from the can and, oblivious to the rain still thundering on the tin roof, collapsed into my sleeping bag.

During the days following, as I toiled to spruce up the cottage and build furnishings to suit the future life style, I was to live in a state of anxious sensitivity to my surroundings. Every unusual incident assumed the importance of an omen of good or ill for the future, each moment of wild beauty glimpsed eclipsed by something that caused fearful doubt.

When I went down next morning, rain still teeming in heightened south-west gales, I was horrified to find both boats, which I had hauled up on to wooden planks, were swamped and banging about in the waves. But for the intervening floating lumber, much of it now scattered a hundred yards along the lochside, they would have been smashed up against the rocks and destroyed. Now I was living by fresh water for the first time I had imagined that at last I would not have to cope with the tides of the sea, but the incessant rain had caused the loch to rise two feet overnight. As I laboured knee deep in water to bail them out faster than the waves filled them, the loch seemed to be trying maliciously to wreck my boats, as if angry at this interloper who did not follow a traditional pursuit like crofting with sheep. Then I realised these waters and the cradling hills had existed long before the coming of the sheep which caused the dispossession of so many Highland clans in the 1790s.

While each wave crashed in as if personally directed, I flailed away with a bucket until I had both boats floating again so I could haul them out. Some of the items I had left on the bank – cement, plaster, candles, tins of paint – had been scattered along the shore. I had to laugh then, for each time I had moved into a new wild place I had lost my first bag of cement in some such way. I should have remembered and carried it up before running out of strength. This time I decided to foil the nemesis and use it before it set hard.

Feverishly I mixed in fine gravel, then dashed about the cottage with bucketfuls, filling holes in the walls and climbing up the wooden scaffold and about the rain-slippery roof to patch up the chimneys. Prodding the cottage’s foundations with a crowbar, I found about two cubic feet of stone and old mortar on the south-west corner had decayed. I chopped the rot away, sledgehammered in more squarish rocks, trowelled the last cement into the crevices then smoothed it all off. I resisted the temptation to crow over cheating the loch. I had long learned that wild places can take a nasty revenge on newcomers who get too uppity – and at Wildernesse I could sometimes feel a presence, as if I were being watched by the spirits of those who had gone before.

It was no use sorting out the impossible piles of gear until the cottage’s inner walls were decorated so for the rest of the morning I shovelled flaking plaster from the study walls and put on fresh. I painted them white, to give more light from the single window. That afternoon the rain ceased, the light improved and while I only had the place on a twenty-year lease I walked round the new land with a feeling of proud possession. I now saw its full beauty as the trees still held their summer foliage.

West of the cottage stood a four-acre conifer wood filled with scaly red-barked Scots and other pine trees, silver and Douglas firs, with small ash trees, rowans, oaks, birches and holly in the clearings. A thirty-foot escarpment rose from its centre, leading to areas of mushy swamp, tussocks and hugh boulders cushioned with moss. East of the cottage and right next to it was a triangular wood of largely deciduous trees, great spreading oaks and tall spires of larches, dominated by a huge Norway spruce that was a full fifteen feet round the butt. Linking these giants were dozens of nut-bearing hazel bushes, more ashes, rowans, hollies, birches and occasional windbreaks of evergreen rhododendrons. A grove of stately beeches flanked the burn which ran down the edge of the wood and was the main vein of the mountains for over seven miles. A hundred yards northeast of the cottage the burn flowed over four deeply stepped pools, dropped down a ten-foot fall into the pool that held my water pipe, then cascaded in three separate forks thirty feet on to a tangle of massive gnarled rocks. Little ferns sprang from the fairy grottos in this spectacular waterfall and in the sunshine myriad rainbows were formed from the spray. The two woods framed Wildernesse and with the protection of the hills that rose immediately behind gave it a unique mini climate of its own.

Between the cottage and the loch, itself framed by a fringe of alders and ashes along the shore, was a 1½-acre patch, now almost totally engulfed in six-foot-high bracken. Well, I would clear this wild tract by hand scythe, not by chemicals, though it would mean cutting the virulent weed back several times a year, to increase the wild flowers and food plants for many insects, bees, and beautiful butterflies and moths. From it too I would wrest a vegetable patch. But right now I had to sort out the interior of my little dwelling.

When I found an uprooted larch tree leaning over at an alarming angle and creaking in the wind I had an idea. Among the lumber I had towed over was a huge plank of red pine, fourteen feet long, a foot wide and four inches thick, riddled with decorative teredo worm boreholes, that had drifted up on a sea beach at Shona. From this I could make a mantelpiece above the fireplace in the study. I also needed two stout logs to frame the fireplace and hold up the mantel, and the backs of these logs would need to be flattened, laboriously with an axe, to fit against the wall.

As I watched the fifty feet of the fourteen-inch-diameter larch swaying up and down, I thought that with a little care I might use the weight of the tree to crack the backs off the logs I needed. I had only an old logging handsaw and with this I perspiringly cut two-thirds through the larch about twelve feet above the roots. Sure enough, there was a sharp report – and a two-foot crack appeared neatly under the cut. I then made a similar cut four feet nearer the roots, to give me the first log. The crack widened until it almost reached the saw. I made a third cut another four feet nearer the roots but by now the top of the tree had come to rest on its branches on the ground. These I axed away one by one and the tree sank further, the split catching up with the saw. With a few sideways axe strokes against the last fibres I had my two four-foot logs, each with a third of its width split off right down its back. I de-barked them with a hand axe, peeled them until they gleamed yellow, and soon had my fireplace’s log frame and massive mantel in place.

By nightfall I had knocked together from fish boxes and other lumber two sets of bookcases and camera shelves to flank each side of the fireplace. I found by cutting the side planks of the shelves at a slight angle they tilted into the wall and the weight of the books held the whole lot glued there, by gravity.

During the following days I had no time for debilitating doubts about the rightness of my move but took refuge in dawn to dusk work. I painted the chimneys with red oxide, replaced some rusty sheets of corrugated iron on the roof, renewed washered nails, wirebrushed off rust, and slapped costly green bitumen paint – to blend better with the landscape – over the entire fourty-foot roof until my left arm shook with fatigue as it propped up my weight on the scaffold and my right flailed away with the brushes. I cut the rest of the pine slab into two four-foot lengths and made a solid workbench for future carpentry. From some piping framework found on a rubbish dump in London, and more odd lumber, I made a record and battery player ‘coplex’, then put up more bookshelves, kitchen shelves, and fashioned a working area near the two-burner camp cooker from an old discarded table top. I decorated the other walls, painted the wooden ceilings after brushing them with woodworm fluid, and cut and hauled firewood for the coming winter. As I only had the handsaw for the first years, I used log hauling and cutting like a city man uses visits to a gym – as an antidote to hours at the writing desk. Thus it became less of a chore, and I soon had the old woodshed behind the cottage half full of fuel.

One problem was the big boat. I didn’t want to haul its 500 lb weight over planks or logs every time I returned from supply trips, which would also wear out its hull. So with fourteen-foot planks and 2-inch by 2-inch poles as ‘rails’ held apart at the right distance to fit the rubber wheels of the trolley by 4-inch by 2-inch struts, I made two portable (just about) runways. Although the loch level rose a few feet after rainstorms one runway could be put into the water at the right depth, the boat could be slid on to the trolley, then winched up to the end and on to the second runway. Then the first runway could be put at the end of the second, the boat winched up further, and so on until I had it a safe distance from the loch.

To leave the boat in the water at the pine wood where I parked the Land Rover on supply trips I evolved a slip rope system. I obtained a heavy anchor with a galvanised metal ring on its top. To this I tied a pulley. With two ropes through the ring and one through the pulley I thus had three twelve-yard-long ropes from the bow that joined up with nearly a hundred yards of single rope tied to the stern. When I reached the far end I dropped anchor, paddled stern first to shore, hopped off with my gear, then with gentle tugs hauled the boat bow-first back out to above the anchor before tying the rope to a pine root. This way I had three ropes holding the boat to the anchor and even in storms, provided I didn’t leave it too long, it was unlikely all three would chafe through.

The advantage of both systems was that I never needed an unsightly mooring buoy, nor a permanent structure for hauling the boat out, to blight the wild landscape. When the time came to depart again I could, like a nomadic Indian or Arab, do so without leaving any trace.

It was my first supply trip that brought back doubts as to the wisdom of my move. I hit into two hailstorms, the second squall so thick with the falling, bouncing stones I had to throttle down because I could see no further than ten feet. But it soon passed and I reached the pine wood safely. The trouble was that just to get mail and supplies, for I also had to drive a further seven miles to the village, took five and a half hours.

It was a rough trip back too and when I arrived at my beach in the near dark, I could not clearly see the trolley and runways. Waves crashing on shore made it impossible to use them anyway. I turned the bow into the surge at the last second, leaped off, and, using each bang of a wave as a natural helping shove, hauled her out on to planks. So fast had these movements to be I slipped on the rocks in the dark and gashed one hand.

The following day dawned in the first bright sky since my move and helped restore some optimism for the future. I had just finished painting one outside wall when my gaze fell upon the calm shimmering loch. To hell with work, I thought, I’m going fishing. It was rather late in the year and all I knew about Scottish fresh water loch fishing then was that you could troll an artificial spinning lure slowly behind the boat for salmon. I had done this kind of fishing in Canada and still had my lures – so out I went in the small boat.

The sun was high in the sky and the molten glassy surface of the loch mirrored the tiny stunted firs and pines on some nearby islets. Great dark cormorants, clinging to rocks with reptilian feet, dried their jagged wings in the sun. I hoped that meant there were plenty of fish in the loch. As I headed east, the mountains on either side rose precipitously from the shores, perfectly matching their reflections which blurred and vanished as the small bow wave rode over them. The slopes of the upper glens and corries far ahead were clothed in many shades of green, like velvet cushions thrown down by the hand of God, and as little clouds moved overhead, single shafts of sunlight burst through to illumine them one by one, as if each were saying: ‘Now, now. Look at my beauty next.’ In one small inlet white water lilies swayed in a slight breeze above their flat leathery leaves, anchored by snaky stems, and when I looked down the water was so clear, the bottom so far below, I felt as if I were magically suspended from a height.

Over all hung a haze of a golden blue harmony in which boat and human seemed to move in an enchanted dream, and the sense of space and wildness was overpowering and sweet. I caught no fish but just to be there was food enough for the spirit.

It was the next day, the last of September, that my doubts returned. I woke to find a white mist lying like a wreath over the loch, separating me from the rest of the world. ‘But,’ I wrote defiantly in my diary, ‘I care less and less for the world and what people may think of me. There were aeons when man didn’t exist and there’ll be aeons more when he’s gone. And when nature returns to take over the blemished land, nothing much will have happened. And yet – I am in the same trap. Just hope I can get my work done before I go.’

As the mist cleared, sucked up suddenly as if by a giant vacuum, it revealed the hills behind in stark blazing light. Up there lay that wildlife kingdom whose secrets I had come all this way to know. It was time to start the real work, I decided. I put camera, lenses, film, notebook, and a piece to eat into my backpack, my fieldglass into a top pocket of my camouflage jacket, and set off on the steep climb northwards.

At first I headed up the burn itself, surprised after a half mile at the depths of the gorges through which the waters had carved their way over thousands of years. Where the sides were sheer I climbed the slippery rocks above the flowing water, then headed among the stunted trees of the less steep sides, warily skirting sheer drops of thirty or forty feet. There were places here where no sun ever shone yet the foliage was lush, with spleenworts and thick lichens with flabby leaves that hid the white bark of the birches. The air was damp and noisy and filled with spray mist below the many falls.

On small ledges tiny ashes, alders and willows grew where no sheep or deer could get at them. But not a single bird or animal did I see. I criss-crossed the chasms until I emerged beyond the first high ridges. Here the land opened into broad meadows, spiked with sudden rock faces and filled with deep tussocks where I learned to keep close to the slow tawny waters of the burn that now meandered more lazily through the shallower country. Here were narrow belts of bright green grassland along the banks where the soil, being well drained and following occasional limestone strata, was more fertile than the wet peaty acid ground that spread out on either side. The oval droppings of deer showed how much they favoured these small oases for grazing.

After two miles I came to an isolated black tarn set in a broad shallow bowl of black peat at about 1,600 feet but not a fish disturbed its surface, and when I looked into the clear water there seemed no sign of insect life. I headed on across the expanse of undulating hills and as far as I could see there was no sign of man either. It was wild, bare and open, like a moon landscape, and I felt few men could ever have set foot there. I walked on between the tussocks until I came to a ridge overlooking a great glen stretched out far below, and then, on the side of it way down low I saw the bracken covered undulating furrows of some ancient ‘lazy beds’ where potatoes had once been planted, and below them a few lost stones of a tiny dwelling. It was hard to believe small crofting communities had once used these wild places, taking their cattle high and sleeping out with them during their summer grazings. Across the far side of the glen reared the twin cones of mountains whose peaks nearly 3,000 feet high poked above a ring wreath of clouds.

Almost four miles I had climbed and walked and I had seen no wildlife whatever, certainly not an eagle, nor even a buzzard, raven or crow. What kind of country is this? I wondered. How can I study the wildlife of these hills if there isn’t any? How much wilder, wider, bigger and more empty they seemed than the punier hills of Shona island. How hard would I have to work to study anything here? I had a fearful feeling that at forty-five I had come to this wild place too late, that the ability to cover twenty miles a day of such hills on foot was over for me. What had I done? What foolish move had I made?

I turned, feeling downhearted, but just as I did so I saw some brown lumps on a hill slope over a mile away. I looked through the fieldglass. At last! There was a huge herd of red deer hinds, calves and yearlings. Some were sitting down as if chewing the cud while others were grazing and I counted forty-seven but as some walked on to the skyline I realised this was not the whole herd and there must be even more on the other side.

I was cheered by the sight but also realised if I had been after studying deer that day I would have had a five-mile climb-walk before the stalking even started. Something stirred at my feet – a fluffy buff-white Smoky Wainscot moth was winnowing its wings and scrabbling eagerly over the grasses after a female whose wings were more blue-grey and which was clinging with upraised body to an asphodel stalk. Nothing else mattered to him as my camera clicked and he quivered towards her, antennae vibrating, with all the amateurishness of the first timer, his white tail fanned out, trying to set it on hers. All that way I had walked and seen nothing but some deer in the distance and there, in the middle of nowhere, was the trembling ardour of young love!

It’s all right for you, pal, I thought. I stumped back down the steep slopes, the camera pack heavy on my back as I negotiated an overgrown rockfall where tufts of heather concealed the gaps between massive boulders, and went home. Seven hard miles for a photo of a couple of moths!

I had known this would be a hard world to really come to know. I had yet to learn that these miles of wild open hills, so different in every season, had to be approached like mysterious, even desirable, gods, to whose secrets one would never gain access without patient perseverance, a certain stealth and cunning, and above all, love; that spring was the alluring nymphet, summer the mature but capricious goddess, autumn the crotchety god losing his prime, and winter a vicious old god of withered skin and frozen bones; and that while all their secrets were revealed but slowly they would be worth all the more for that.

Chapter 2

First Wildlife Adventures

After a week of early autumn storms, mid-October blessed Wildernesse with an eight-day Indian summer – the clouds rolled away, vanishing like battle battalions over the high horizons, and the sun blazed down with a fierce bright heat seldom felt during the misty hazes of the Highland summer. As it scorched through the window, made white paper dazzle the eyes, all desk work was impossible.

As I de-mossed and painted the cottage exterior, cut and carried fallen logs from the woods and hacked away the bracken to clear a vegetable patch and cultivate the wild grasses and flowers, the first wildlife happenings began. The woods were now as filled with bird songs as if it were spring – strident chipping wrens, the pink pinks of gaudy chaffinches, the silvery trills of robins seeking new territories after breeding. High in the conifers goldcrests zinged, and occasionally I caught glimpses of a great spotted woodpecker flashing his cancan colours of black, red and white among the trunks, or heard him drumming on a dead ash. From thickets came the chirring notes of tits and the slaty squeaks of tree creepers who worked their way in spirals up the trunks, searching for insects in the bark. Large clusters of blackberries had appeared on the brambles, and I decided not to clear these away but trim and cultivate them. Blackberries were as fine a fruit as any, after all. The hazel bushes were overloaded with nuts and I saw the red squirrel I had watched when I first camped out at Wildernesse the previous winter. He was leaping busily, tail flicking to help him balance, as he gathered the nuts and acorns from the oak trees.

That gave me the idea to collect nuts for my own winter supplies. Out I went with an old blanket and shook them on to it from the whippy branches, so as not to lose too many in the bracken. Even so I left more than I took for I could do without them better than the squirrel.

When I was tired from the outdoor jobs I just lay down and tanned myself in the sun. Then I could watch a great black and blue striped aeshna dragonfly which had emerged from its leafy hiding place during the storms. It hawked about, swooping with contemptuous ease to catch flies and gnats in the scoop formed by its massive jaws and thick black legs. Occasionally it came to investigate my face, hovering with rattling wings and treating me to the frightful primeval stare of a pair of bulging multilensed eyes that blazed like twin mirrors with a metallic sheen. Then it would spot some worthy prey, like a big buzzing bluebottle, sweep up like a falcon at a finch and snatch it from the air.

Dragonflies have long been my favourite insects for it was they who helped start my love affair with nature. As a city boy of twelve on his first country holiday in Sussex, I had discovered a little wild pond in the woods, and above it floated these incredible creatures of darting fire. As they hawked over the reeds, snatching insects on the wing, they had ‘minds’ of their own, knew exactly what they were doing. Clearly, they were the dashing Red Barons of the insect world. Dragonflies are a miracle of evolution and have been hunting this way for 340 million years. Even the aeshnas we see today are Britain’s oldest flying predators and were hawking the skies 150 million years ago, long before the first dinosaurs appeared.

Their eyes are among the most efficient in creation, and contain over 20,000 lenses. Few insects can see six feet in front of them, but if just one of a dragonfly’s hexagonal lenses perceives a fast movement up to forty feet away, its lightning reflexes and acrobatic skills allow it to investigate immediately, make a capture – or flee. No wonder there has been no need to change its form in all that time.

It is sad that dragonflies are in decline, especially in the south of Britain, where many of their breeding ponds have been polluted, allowed to silt up or filled in for development purposes; where rivers have been ‘improved’, cleared of vegetation, or tainted with insecticides and herbicides; for these magnificent insects are immensely useful to man himself. Both as a larval nymph in the water and as a flying adult, one dragonfly kills thousands of mosquitoes, midges, flies, and wasps in its lifetime. When it hovers round farm animals it is not to sting them, as was once believed (it has no sting), but to catch pests like bot flies, whose larvae invade the animals’ noses and stomachs, or green-bottles whose maggots feed on any injured flesh.

For days as I watched my hawker hunting about in systematic figure-of-eight beats I wondered if, like myself, he was an accidental solitary. Then, on 14 October, I saw him put the dragonfly’s mating technique into action. If it left much to be desired from the romantic view it was stunningly effective. Male dragonflies don’t fool around. Out of nowhere a browner female came winging round from behind the cottage. He shot upwards at great speed, hit into her with an audible clash, then seized her neck with the special anal claspers at the end of his 3½-inch body. Down they went, their wings buzzing noisily like a clockwork train left running in the grass. She seemed totally submissive to his headstrong desire and within a minute both flew back into the air, their wingbeats synchronising, and landed on a bracken fern where she curled her tail up under his body and mated. For several more minutes they flew round the area in tandem, then he let her go. I watched her fly to the loch’s edge where she would lay her eggs on a water plant, while he flew, unsteadily now, to find a perch for the night.

He flew spasmodically for only two more days, his wings rattling as if with old age, his hunting days over, until on 17 October came the first small snowfall of winter and I saw him no more. He had perished, but not before completing his life’s task.

By now the red deer were rutting high in the hills and occasionally, as I tried to finish the cottage repairs for the winter, I could hear the challenge roars of the stags. On 21 October I heard a loud roar near the cottage and went out with the camera to see a single old stag on the hill above. An old ‘switchorn’, with narrow inverted antlers holding only six tine points, stared back at me truculently as the camera clicked. Maybe he knew 21 October marked the end of the stag shooting season.

A poor specimen for my first stag shot at Wildernesse, I thought. I hope they aren’t all as poor as that!

By mid-November the first winter gales were stripping the trees, heavier rains had turned burns into seething white veins in the hills, and the dull roar of the woodland waterfalls became the undertone to all sounds at Wildernesse. The gales and increasing cold turned the supply trips into more perilous teeth-gritting journeys, but at least some magnificent whooper swans, back from breeding in Iceland and northern Scandinavia, now flew over the boat, their long graceful necks extended, white wings whistling. Some mornings too a lone heron would be patiently standing to catch water creatures in the burn, unafraid of the red deer that might be grazing on the opposite bank.

The first heavy snow fell towards the end of the month, and after it had lain three days I felt sure that a hard winter lay ahead. But on a supply trip I was surprised to find the village completely without snow. It was only a few miles nearer the sea yet the climate was warmer. Again I wondered about the wisdom of my move, for by early December the mountains round my home had become white icebergs. My water system, a black polythene pipe from the burn, was often frozen up and I was reduced to carrying buckets of water for washing and cooking.

Small herds of red deer hinds and calves, driven down from the tops by the ice and snow, started to use the woods as dormitories. Early one morning I looked through the workshop window and saw a hind apparently dancing in the west wood. She seemed to be making a real sensual feast out of it, her feet moving to a kind of rhythm and her long neck sawing up and down to a regular beat. But when I got my fieldglass I saw she was not dancing in fact but using a small Scots pine as a rubbing post. First she rubbed her forehead on the rough bark, licked it with her long pink tongue, then with closed eyes rubbed the sides of her face gently, arching her neck like a bow so she could also work the bases of her ears against the tree. She paused, looked around, perceived no danger, then moved closer to the pine, and like a horse trying to shake off a bridle gave both sides of her neck a good working over. Next she switched herself round, backed up to the tree and with front feet firmly braced performed a cervine version of the ‘shimmy’ dance, rubbing her backside to and fro. Apparently this gave her great joy for her eyes closed, her face assumed a soppy smiling look and her lower jaw dropped open in a leer of pleasure.

Finally, her toilet completed, she stepped away, shook her coat so vigorously it seemed almost detached from her body, then followed the other deer up the slopes to graze on ling and heather. I went over later to find two of the smallest weedy Scots pines had had their trunks rubbed smooth up to a height of about five feet. Deer do this not only to dislodge pests like keds and ticks but for the insecticide qualities of the resin, which also gives the guard hairs of their coats a distinct gloss. They appear to enjoy the odours of its scent, too. They will rub on a favourite tree for two or three years until all the bark is off, the trunk wood becomes highly polished, and the tree dies. I looked up but both pines still had their full foliage of needles.

Two evenings later I came the closest I had ever been to a herd of wild red deer. I went out quietly at dusk, saw six hinds and two calves working downhill, and just had time to station myself under a large hazel bush. Wearing camouflaged jacket and bush hat, both washed in pine needle juice, I stood back amid the wands of new hazel growth and kept still. The deer slowly walked towards me, splitting up round the bush until the nearest was a mere ten yards away. An old hind with a grey face and torn ears with yellowish patches among the dark hairs, clearly scented something for she raised her head attentively.

The south-east wind was blowing what should have been my scent towards her but it was a dry day and with nothing dangerous in sight her suspicions eased and she carried on grazing. They walked right past me and on into the front garden, and I could hear their cloven feet squelching in the marshier parts. It was too dark for photos but they were exciting moments. I even managed to get back to the cottage without startling them, moving slowly, an inch at a time, and freezing motionless at the first sign of suspicion. When I was back indoors, pleased with myself, they even stayed when I lit the paraffin lamp. I felt they were beginning to know that I was harmless. One night they appeared outside the window a few minutes after I had put some Beethoven on to my battery record player, as if attracted by the music. At least it didn’t deter them.

On 19 December, after three days of sporadic blizzards, the snow lying a foot thick, I had a more extraordinary experience. I saw a hind walk across the garden to the west followed by (judging from the width of its head) a stag calf. I watched from between the leafy branches of a rhododendron as the mother turned north to the first slopes of the hills. The youngster went slower, snipping off shoots and bramble leaves and nosing about under old bracken stalks. Then, as if trying to shelter from a new snow flurry, it walked behind an old ruined wall. Hoping for a close shot I approached quietly, reached the wall and peered round slowly. There, right before me, was its white-buff anal flash and two rear legs both trembling with the cold.

I don’t know what came over me but with camera swinging from my neck I put my left hand on the wall and made a grab for the leg nearest to me, knowing the deer would leap and kick. It did, like a kangaroo, but I held on, moving upwards with it, and when it came down again I hauled it off its feet. Its other leg, the right, flailed away as I expected; if I had grabbed that one I would have had my face kicked in by the left. I hauled the hefty calf back and got my other arm round its neck as it snorted in my ear.

In those brief moments I saw it was in fine condition, spine well covered, mouth healthy, and I realised that if I had been starving, a man on the run, I could have killed it with a knife. Suddenly it let out a loud braying ‘Bleah!’ and I let it go. It just got to its feet and stood there, looking round at me, bewildered. I took a photo. The click startled it back to reality and it ran a couple of steps, then stopped to look at me again from behind a fallen larch. I took another shot. This time the click made it go, leaping the remnants of another old wall, and I was lucky enough to get a shot of the actual jump.

The calf ’s mother was moving above in agitation. When the calf joined her they both stopped and looked back at me again, their expressions seeming to ask ‘What the hell did you do that for?’ I felt mighty pleased with myself at the time – to catch a wild deer by hand was surely a rare experience, and what was more I had the photos to prove it. Looking back, however, it was an unnecessary and foolish act, born of the hunting instinct latent in man, and I never attempted it again. Giving deer such frights in winter, especially if they are in a weakened condition, is neither sensible nor kind, for I have since found out they are susceptible to shock. Three hours later, however, both mother and calf were back, this time in the east wood.

As if that occurrence was not enough, I woke up some mornings later to see sleepily what looked like some brown sticks waving in front of the window. Then a big head with slit-pupilled eyes looked in. It was a stag, calmly observing me in bed! When he looked away I sneaked out, shivering in just a vest, and took a photo from the door. The trouble was that while red deer were now easier picture targets, the winter light was too poor for colour film shots.

I realised too that because the deer were now using the little woods for nightly shelter, their browsing, together with that of voles and occasional sheep, meant the trees could not regenerate naturally. Well, I would have to do something about that.

Now was the time of the winter solstice and the perpetual darkness in daytime, increased by the high hills and the nearby woods, was at first as depressing as it was bad for the eyes when I was working at the desk. It was far darker here than my home on Shona, under the wide open Atlantic skies, had ever been. I had to light the lamp around 3 p.m.

Two days later I boated back from a supply trip in a blinding blizzard. The slippery snow made it harder to pull the boat out. My mail brought depressing news – the novel which I had written three times over seven years had been turned down and for the fourteenth time and I felt it would never sell. The outline of my book about the Canadian wilds had also been rejected by a publisher who had first shown great interest, but finally didn’t believe I had trekked alone in grizzly bear country. I sat for a long time in silence only relieved by the hissing of the paraffi n lamp, trying to face the fact that I was now a failure, in every sense. No wife. No children. Hope receding, resignation setting in. And no human around for miles. No real friends left anyway. It seemed I had no chance either of even communicating a few experiences or thoughts by writing books. I had not only cut myself off for no purpose; I was also being cut off by forces beyond my control. It seemed almost as if society was exacting revenge for my daring to flaunt normal concepts of community and the need for companionship.

Next day, water pipe frozen up, I went to fill my buckets in the burn. There was a dead hind washed up on the rocks by the flow of the water. Her upper eye was missing. Her upper haunch had a gaping red wound where a fox had been tearing away the flesh which was in fresh condition. I took hold of the leg and heaved her out and found shotgun pellets also in the haunch. Only a fool would use a shotgun on a full-grown deer hind, so it was probably the work of a poacher who had shot as the hind was running away.

I back-tracked her twin slots through the snow up about two hundred yards into the hills and found a round depression between the tussocks where she had apparently rested. Around it were her droppings, made as she had lain there. How far she had walked while wounded I could not tell but somehow she had found the strength to stagger down to the burn and had died after stumbling into the icy water while trying to cross it. With the weather so rough now I didn’t know when I would be able to get out again, so rather than waste the meat I sadly cut off the good haunch, skinned it and hung it in the woodshed. In fact I was hemmed in by gales for over two weeks and baked chunks of the haunch in tinfoil over the log fire.

Depressing news also came from the faint radio. Power strikes had plunged some cities and hospitals into darkness and it also seemed petrol rationing was imminent for coupons had just been issued. Even if I had had somewhere I wanted to go for Christmas and New Year, what with the petrol problem and the blizzards, the chances were I couldn’t get south anyway. Walking back from a short trek one day I glimpsed the cottage from an unusual angle in the bare woods. It looked very isolated and lonely. Lonely house, lonely man, I thought. Good company for each other.

I did what I always do when the loneliness sets in – turned to the creatures of the wild for company. I was already putting out food scraps, and bright colours and cheerful calls flashed and sounded around them as little robins, tits and finches hopped on the window sill. If I couldn’t improve my own lot I could at least improve theirs.

PART TWO

Chapter 3

A Bird Table Theatre

It was a robin which shamed, hustled, me into making the first bird table at Wildernesse. I was picking blackberries one November day when it came flitting through the bush on its knock-kneed legs, scolding with loud ‘tick tick’ notes. ‘It’s all right. I’ll leave enough for you lot,’ I said. The robin flicked his wings towards me, bobbing indignantly as if to say ‘Get out of it’ or, being a Highland robin, ‘Awae wi ye!’

At first I made a miserable effort, a square foot piece of wood on an old post by the kitchen window, and set a slice of bread on it each morning. Within a week the ‘daily bread’ was disappearing before dusk but I only had occasional glimpses of chaffinches, two great tits and a blue tit when I went into the kitchen to make lunch or a cup of tea. It took me two weeks to realise I had not been clever; while feeding the birds I had failed to provide free entertainment for myself. So I took a morning off from trekking and writing on 1 December and made a really picturesque avian canteen. I cut a slab from a thick red pine tree butt that had drifted on to a beach half a mile away and nailed a strip of wood along one side to stop the prevailing south-westerly winds from blowing away the food. On one edge, to give it a homely touch, I built a nest box of larch slabs, then set the whole edifice on a thick post a mere nine feet from my study window.

One mixed blessing of having no electricity was that I could not run a television set – and so could not succumb to the temptation of switching it on and slacking in my desk or outdoor work. But in following winters I lost many man-hours through watching this little wildlife theatre, so easy to make, cheap to run, and for which no licence fees, rates or taxes had to be paid. On this palace of varieties I have enjoyed as much comedy, farce, drama and, indeed, tragedy as from any television set.

The first character upon the winter stage, as befits the boldest or tamest of small British birds, was the robin. This jaunty clown who, in folklore, gained his red breast from being wounded when pulling spines from Christ’s crown of thorns, or in another version, from being burned when taking a brand from the Devil’s forge to bring man his first fire, arrived early one morning from the east wood. With long thin legs spread wide as if to make room for the pot belly, he landed on the spray of plum tree twigs I had nailed to the table for birds to perch on while eyeing the goodies below.