Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

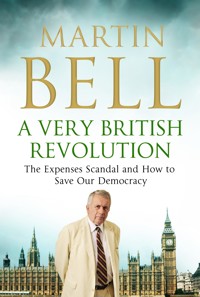

The revelations over MPs' expenses that began in May 2009 ranged from petty thieving to outright fraud and sparked a crisis in confidence unprecedented in modern times. This was a 21st-century Peasants' Revolt - an uprising of the people against the political class. Ordinary men and women with political views across the spectrum were by turns amused, incredulous, shocked and then bitterly angry as the disclosures on MPs' expenses flooded out. From Home Secretary Jacqui Smith's bath plug to Conservative MP Sir John Butterfill's 'flipping' of his constituency home - a now-notorious manoeuvre that required him to refund GBP60,000 to the taxpayer - the exposure of MPs' expenses revealed Westminster's culture of quiet corruption like never before. Drawing on his experience as an MP and as a member of the Committee on Standards and Privileges, Martin Bell explains how the expenses crisis arose and, most compellingly, lays out his prescription for healing the deep wounds inflicted by the scandal. As Martin puts it: 'The revolution will not be complete until all the rogues in the House are gone and public confidence in the MPs remaining is restored.' This is truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to revive British politics, and the rebuilding starts here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A VERY BRITISH REVOLUTION

The Expenses Scandal and How to Save Our Democracy

MARTIN BELL

ICON BOOKS

Published in the UK in 2009 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

This electronic edition published in 2009 by Icon Books

ISBN: 978-1-84831-100-8 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-102-2 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN: 978-1-84831-096-4) Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road, Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Published in Australia in 2009 by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada by Penguin Books Canada, 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright © 2009 Martin Bell The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

Contents

Introduction

1 Bath Plugs, Moats and Duck Islands

2 Accidents Waiting to Happen

3 The Backlash

4 Off with their Heads!

5 Black Thursday

6 The Honourable Scapegoat

7 Mr Speaker

8 The Independent Deterrent

9 A Personal Decision

10 The Political Class

11 Downfall

12 Soldiers, Bankers and Swindlers

13 Afghanistan – A Study in Contrasts

14 An Act of Sabotage

15 A Democratic Blueprint

16 Restoring Trust

Notes

Martin Bell OBE is one of the best-known and most highly regarded names in British television journalism. As a BBC reporter he has covered foreign assignments in more than 80 countries and eleven wars including Vietnam, Nigeria, Angola, Nicaragua, The Gulf and Bosnia, where millions watched as he was nearly killed by shrapnel. In 1997 Martin became the first Independent MP to be elected to Parliament since 1950, and he has since campaigned tirelessly for trust and transparency in British politics.

His previous books are In Harm’s Way (Penguin, 1995), An Accidental MP (Viking, 2000), Through Gates of Fire (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003), and The Truth That Sticks (Icon, 2008).

Swindlers’ List

I wish I had my own duck house,Redacted and anonymous,A shaded pool where ducks could float,A pond, a river or a moat,A place unto the manor bornWhere moles would not uproot the lawn.I was not born to privilege,But loitered at the water’s edge,And played the Honourable MemberFrom January to December.I wish to thank the voters’ senseFor choosing me at their expense;On their behalf I did my best,Including things they never guessed.Though my accomplishments were zero,In fiddling I was next to Nero,I was a self-philanthropist,Master of the John Lewis List;I had a profitable inningsAnd duly pocketed the winnings,The subsidies, the perks, the pay,The petty cash, the ACA.The Tudor beams, the chandeliers,The bills for swimming pool repairs,The hanging plants, the trouser press,Nothing exceeded like excess,The whirlpool bath, the horse manure,Whiter than white, purer than pure.And so it was until, alas,The MPs’ scandals came to pass.I was your Honourable Friend –A pity that it had to end.And then to avoid the sneers of Mr PaxmanI wrote a cheque and sent it to the taxman.

Introduction

We have been through a period of political revolution the like of which we have not known in our lifetimes. It has been very British and very peaceful, but nonetheless profound. Its outcomes will permanently change the nature of our politics and especially that of the House of Commons. It has arisen from the publication of the detailed expenses of Members of Parliament, which were in most cases beyond reason and in some beyond belief. They ranged from petty thieving to outright fraud. They provoked what can perhaps be best described as a 21st-century version of the Peasants’ Revolt – an uprising of the people against the political class and its practices and patterns of corruption. Not all MPs were equally guilty. Some were not guilty at all. But the corruption was revealed to be widespread and pervasive. We have been witnesses of something unique in its character and which will, I believe, be positive in its consequences.

It was hard to know whether to laugh or cry: we did a bit of both. ‘Corruption,’ said Peter Ustinov, ‘is nature’s way of restoring faith in democracy.’ Great reforms are driven by great scandals. And this has been one hell of a scandal. Not only have we lost faith in our politicians: they have even lost faith in themselves. So the perpetuation of the status quo is not an option for any of us. These events will be studied for years by those who will write the history of our insurrection. This book, which was written as it unfolded, is an attempted first draft of that history.

So rich is the seam of source material that when I told a friend about it, he asked: ‘How many volumes?’ Just one will do for the time being. Others may follow. The list of misdemeanours goes on and on. Not all the politicians caught up in the scandal have yet been driven from office. But it has changed the weather in Westminster, the style of political campaigning and the terms of trade between the parties. So it is a very British revolution. It has really started something.

Alan Duncan (Conservative, Rutland and Melton) was one of the MPs who found himself in the thick of it. Not only was he Shadow Leader of the House, and therefore responsible for his party’s policy on MPs’ expenses, but his own gardening costs were found to be on the high side, including £598 to overhaul a ride-on lawnmower. A protester had himself filmed digging a pound-shaped flower bed in Mr Duncan’s lawn in Rutland and planting it with flowers. The video became an instant hit on YouTube. The MP wisely asked the police not to prosecute, and he said: ‘The outpouring of fury we are witnessing is like a spring revolution.’ But he also thought that at £64,000 a year MPs were underpaid and ‘forced to live on rations’. The MP for Rutland and Melton was removed from the Shadow cabinet.

There are those who believe that the outpouring of fury will pass like a sudden storm, and that when it has passed they can carry on much as they used to. There are others who understand that it has changed our politics permanently. I am firmly in the second camp. We cannot return to where we were, which was the politics of the pig trough, because the people will not stand for it. The revolution will not be complete until all the rogues in the House are gone and public confidence in the MPs remaining is restored. The overhang of the scandal is so great that even new Members in a new Parliament will find themselves initially on probation. The restoration of public trust in public life will be work in progress, perhaps for many years. They will have to keep at it. And so shall we.

My only qualification for writing this account of the ongoing revolution is that I am a taxpayer and a true-believing democrat who was once an MP and a part of the Commons’ system of self-regulation, the Committee on Standards and Privileges. I was there. I sat back and marvelled. I saw what worked and what didn’t – especially what didn’t. For all its neo-Gothic grandeur, the House had something of the Wild West about it: too many villains, too few sheriffs, and laws that turned out not to apply to the regulars in the saloon bar. Even ten years ago, from the vantage point of Committee Room 13, the regular meeting place of the Select Committee on Standards and Privileges, I believed that the regulatory system, such as it was, would one day hit the buffers. I had no idea that the crash would be so sudden and spectacular. Some resigned and others were left clinging to the wreckage.

Sir Philip Mawer, Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards from 2002 to 2007, took a similar view. He told Sir Christopher Kelly’s Committee on Standards in Public Life: ‘The recent furore over MPs’ allowances is a car crash which has long been waiting to happen. Not only has the reputation of many decent MPs but that of the “Mother of Parliaments” itself has been seriously damaged in the wreckage. … The damage will take years to restore.’1 He laid the blame on a collective failure of leadership in the House of Commons itself. MPs should have seen this coming, but fought shy of the reforms that were necessary to save their reputations.

This account of the scandal is therefore about more than moats and mole traps. It sets out to explain why and how the crash occurred. It looks ahead to the reforms that are necessary, in a House of Commons which will inevitably, because of its own shortcomings, have sacrificed some of its sovereignty and may yet need to sacrifice more. It analyses the half-measure of the Parliamentary Standards Bill. It draws on a variety of sources: my own experiences, conversations with some of my friends and co-conspirators in the House, contacts with politicians across the country, Hansard’s record of certain key debates, submissions to the Kelly Committee on Standards in Public Life, and the thousands of pages of the MPs’ expenses themselves.

It also sets out an unexpected military dimension. A sharp increase in British casualties in Afghanistan coincided with the news of the widespread misconduct of the political class. It raised a question of integrity: in terms of the military deployments and resources allocated, how could we entrust the lives and futures of the men and women of the armed forces to MPs who had in so many cases proved to be untrustworthy in their personal affairs, had gone AWOL from their responsibilities and who had appeared to exercise their duty of care, in some cases, principally to their bank accounts? While the soldiers were losing lives and limbs, one of Labour’s Defence Secretaries responsible for their welfare was walking away, over a four-year period, with £12,000 in petty cash. How can that make sense? Just work it out: or as the Americans put it, go figure.

I am obviously grateful to the Daily Telegraph, not only for its initiative in securing the documents that showed the extent of this misconduct, but for the thoroughness, even-handedness and sheer bloody-mindedness with which it presented them. Bloody-mindedness is a journalistic virtue. Day after day, the Telegraph and its Sunday sister paper just kept at it, and found gold in the silt that they sifted. They did us all some service. If we had relied on the ‘redacted’ records published by the MPs themselves, we would have had no idea of the extent of their misconduct.

My thanks also to Peter Cox of Redhammer, to Stevie Cook for her additional research, and to Peter Pugh, Simon Flynn, Andrew Furlow, Duncan Heath and Najma Finlay of Icon Books. Thanks of a sort are also due to the MPs themselves, whose milking of the system was so extraordinary that the book took on a life of its own and almost wrote itself. It was a ten-week labour of love – and of doubt and dismay and incredulity. It was also a satirist’s despair, since no parody could have matched the real-world story that unfolded.

From out of this shambles we have to find a way of rebuilding confidence and electing MPs who will deserve the trust of the people. There never was a golden age of parliamentary democracy; but some times have certainly been worse than others, and this is one of those times. What the House of Commons could be is one thing, and what is has become is quite another. It is not too large an ambition to hope for a Parliament to be proud of. So I shall place some signposts along the way. We are not, to be realistic, aiming for an unattainable state of grace, but at least for a politics of less disgrace than that in these past few years.

Chapter 1Bath Plugs, Moats and Duck Islands

It began with an 88p bath plug.

The bath plug was bought by or on behalf of the Home Secretary Jacqui Smith, MP for Redditch since 1997. Along with the bath plug there were other items listed as necessary expenses, including a barbecue and a patio heater. They were all acquired for her constituency home, where she lived with her husband, who was her constituency assistant, and her two children. By any common sense definition it was her main home, since it was her family home and had been for many years; and it was where she was registered to vote. But one of the things we have learned about public life is that common sense flies out of the window when politics comes in through the door. She told the Commons authorities that her main home was her sister’s house in south London, where she rented a room, and maybe a little more than a room, while working in Westminster. This allowed her to claim all the parliamentary allowances that were due, and some that were not (which she duly paid back), on her home in Redditch.

As it turned out, Jacqui Smith’s residential arrangements, in which she switched her designated second home from one property to another, were by no means unique. Other MPs, and other cabinet ministers, did the same, sometimes two, three or even four times. This was because the second home, but not the main home, was subsidised by the taxpayer. The practice was known as ‘flipping’. But it seemed remarkable, and even borderline, when the story came out in February 2009. We ordinary people – including even ex-MPs like myself – had no idea that this was going on. A complaint was made to the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, Mr John Lyon, that Jacqui Smith was in breach of the rules.

Mr Lyon was fifteen months into his post as Commissioner. Unlike his distinguished predecessor but one, Elizabeth Filkin, he was not a rocker of boats or maker of waves. But it will be remembered that Elizabeth Filkin was removed from the job in 2002, essentially for doing it too well. She made MPs uncomfortable by the thoroughness of her investigations; and only now do we know how much they had to be uncomfortable about, which was why they resisted. As Elizabeth Filkin observed, they had the opportunity to self-regulate and they subverted it very, very seriously. The SNP leader Alex Salmond, one of her small band of supporters in the Commons, called her departure a ‘political assassination’. Mr Lyon was certainly aware of the precedent, although he never consulted her. He had a reputation in Whitehall as an official who went into his office, closed the door and stayed there. Besides, he was no more independent than any of the three Commissioners before him. They were servants of the House, and of its all-powerful Commission under the chairmanship of the Speaker. The House of Commons had always stood firm against outside regulation. The theory was that none was needed, since it was a gentlemen’s club of ‘Honourable Members’ who could be trusted, at least by each other.

Mr Lyon initially ruled that he would not investigate the complaint against the MP for Redditch who, like so many others, appeared not to know where she lived. This seemed to me such an extraordinary decision that I wrote to him about it. I had no formal standing in the matter, since I was no longer an MP. But I was a taxpayer like millions of others and had once served on the Committee on Standards and Privileges, to which the Commissioner reports; so I knew how the system worked – or in this case didn’t. I pointed out to him that previous Commissioners had experienced most difficulty with complaints against high-profile MPs, and hoped this wasn’t happening again. I noted that the affair was damaging still further the reputation of the House of Commons, and was sure that he would not wish this to happen on his watch. I politely indicated that I thought he had made a mistake.

He wrote back to me immediately. He defended his decision to take no action, on the grounds that the complaint had been based only on a story in a newspaper, The Mail on Sunday: ‘After careful consideration, I concluded that the newspaper report did not provide me with sufficient evidence that Ms Smith had breached the rules. I came to my own independent conclusion, taking no account of Ms Smith’s position in Government, and I hope without fear of the likely reaction from the press to this judgement.’ But in the meantime he had received another complaint (from a neighbour of Jacqui Smith’s in south London, about how often she actually stayed there) and had decided to investigate that.

Things then got worse for the Home Secretary. It emerged that she had made a claim of £10 for a cable TV service of two adult movies watched by her husband, Richard Timney. Mr Timney apologised and she paid back the money. It was a very public humiliation and clearly distressing for both of them and presumably for their family. There was a hidden dimension to the great public scandals of 2009, in which careers were ruined and reputations destroyed at the turn of a page: in every case they were accompanied by a great deal of private hurt. Innocent people, including children, were caught up in them. But it was the Member herself who had signed the mistaken expense claim. It was the personal pain that was caused by the episode, and the acres of adverse publicity devoted to it, that led Jacqui Smith to stand down as Home Secretary, though not as an MP. Inevitably she lost confidence in herself. She said later: ‘I think I’ve had a harder time than some for less sin, because I was the first person for which there were questions about my expenses.’2 She described herself as ‘The poster girl for the expenses scandal’.3 There has never been a time in our political life when so many MPs, one after the other, have had so much to regret in so short a space of time.

Throughout the spring and early summer the saga of swindles and scandals unspooled – leaving the voters bewildered, occasionally amused and finally extremely angry. The gravy train had left the tunnel and for the first time was out in the open for all of us to see. Many of the miscreants were long-serving MPs who had made a point in their election addresses of calling for thrift, economy and an end to waste in every corner of government. Now they were exposed as the biggest wastrels of all. They were switching homes to maximise the benefit. They were employing accountants to prepare their private tax returns at public expense. They were hiring their relatives and subsidising their families with taxpayers’ money. They were furnishing their second homes, and even their first homes, with luxuries – an £8,000 television set here and a £600 array of hanging baskets there. They were especially keen on trouser presses. They were prodigious consumers of toilet paper. They were pocketing the petty cash. They were even charging for their grocery bills. One of them claimed for dog food and another, rather suitably, for pork pies. On their walls they were claiming for etchings and in their gardens for horse manure and mole traps. The extremists among them were using their allowances to develop an entire portfolio of properties. The spivs and speculators flourished. There was no limit to the feathers that lined their nests. The lists of their acquisitions went on and on. Democracy retreated and kleptocracy advanced.

It was both a national disgrace and a national joke; and it would have been even if the good times were still rolling. But they were not. It seemed that everyone except the political class was feeling the winds of the recession. Ordinary, blameless and decent people were losing their homes and their jobs. The point most frequently made against the Honourable Members was that in any other walk of life, like a private company or public corporation, they would have been handed their coats, escorted out of the door in short order and instructed not to return: the evidence of their wrong-doing might then have been passed to the police. Or if they were soldiers, risking their lives in distant lands on the politicians’ orders, they could have faced a board of inquiry or court martial for a simple £10 discrepancy. The people were united in their outrage. From Luton to Totnes and from Scunthorpe to Bromsgrove, the universal complaint was: Why is there one law for them and another for us?

The most serious cases concerned actions which, outside the walls of the Palace of Westminster, would have been thought to fall within the categories of fraud, embezzlement and the misappropriation of public money. These involved MPs who had claimed reimbursement for mortgage payments long after the mortgages had actually been paid off, and others who had claimed for more than they actually owed. They said – they would, wouldn’t they? – that the errors were inadvertent and made in good faith. They had just been too busy to notice. They were big-picture people. They were better with words than with numbers. Even the Chancellor and Shadow Chancellor, supposed to have expertise in these matters, came unstuck on the details of their claims. As for the Justice Secretary, ‘Accountancy does not appear to be my strongest suit’, wrote Jack Straw over a council tax error in his Blackburn constituency. This too was against all common sense. We all have to pay attention to the bottom line. When expenditure exceeds income we do not have the luxury of closing the gap at the taxpayers’ expense. We cut our spending. Those of us who have been paying substantial sums to building societies for our mortgages for 30 years or more will not lightly forget the day when the payments cease. We have come through. A burden has been lifted from us.

Politicians live in a different world. When Peter Mandelson was under investigation by Elizabeth Filkin over his application for a mortgage on a house in London while not declaring, on the application form, that he had already taken out a loan on his home in Hartlepool, his answer was that he did not know a mortgage was a loan. And now he is the Wizard of Oz. And a peer of the realm. And other princely things.

I shall deal with the open-ended mortgages later. They caused quite a stir when they were first revealed. But to voters baffled by the intricacies of the MPs’ rules, and especially the Alternative Costs Allowance for second homes, the eye-catching items that the MPs claimed for were the little things that people could more easily relate to in their own lives: bath plugs, light bulbs, toilet seats and mole traps among others. (The mole traps were John Gummer’s.) Then came the rather bigger things, like whirlpool baths (Celia Barlow MP) and mock Tudor beams (John Prescott MP). And finally the biggest thing of all, which was a moat.

Douglas Hogg, Conservative MP for Sleaford and Hykeham, was also the Third Viscount Hailsham. He had a good record as a minister in John Major’s government. His father and grandfather had been cabinet ministers before him, though he told me once that politics was no longer a profession that he would recommend to his own children. He owned a substantial manor house in Lincolnshire and the moat that encircled it. The manor house, of course, was designated as his second home. He had a special deal with the Fees Office, the House of Commons accounts department, to help him with the estate’s expenses. These included £2,115 for having his moat cleaned, and further amounts to get his stable lights fixed and his piano tuned; there was also money for a mole man and a call-out charge for someone to deal with the bees. The moat was not specifically claimed for, but not excluded either. Its cleaning caught the imagination of people who did not own moats, stables or even pianos; and who, if they had problems with moles or bees, would pay the cost themselves of getting them fixed. It was the perfect metaphor for the perception of MPs leading privileged lives remote from the rest of us in a world entirely their own. It was also in keeping with the idea of Parliament as a fortress. The symbol of the House of Commons is a portcullis: now we understand why. Mr Hogg, who did not enjoy the adverse publicity, decided to stand down from Parliament and endure no more of it.

The moat immediately became a national talking point. The newly-appointed Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, laid down a marker with her very first official verse, an off-the-cuff couplet delivered during a visit to a school in Manchester:

What did they do with the trust of your vote?

Hired a flunky to flush out the moat.

It was famous abroad as well as at home. To the Americans especially, it was evidence of the undefeatable daftness and dottiness of the British. But the New York Times was faintly disappointed. ‘When British politicians go astray,’ it sniffed, ‘one expects spies or sex. Yet the latest scandal is about Parliament members and their expense accounts.’4 On Comedy Central’s popular evening show, influential in the election of Barack Obama, a British actor put the case for owning a moat to the astonished host, Jon Stewart. Patriotic music played in the background. He struck a heroic pose. It was his Richard II moment.

‘You probably never dug a trough around anything you owned and filled it with stagnant water. My country may not defend itself with guns, but we will encircle ourselves with a trough of filthy water. … And we will fight for this corrupt plot, this filth, this scam, this England!’

It was a topsy-turvy time, this age of scandal, in which the people took the comedians seriously but saw the politicians as a joke.

By a happy coincidence Garrison Keillor, the sage of Minnesota, was in London at the height of the parliamentary revelations and wrote about them in woebegone wonderment for the New York Times: ‘And now, having seen the Speaker walk the plank, the Honourables must go out to their districts in Sodden Wickham and Twitching Bridgewater to explain why taxpayers paid for the cleaning of a moat. A dreadful fate, having to kneel down and crawl in public as the mob flings dead fish and dry dog dung at you. … Forget about Iran – if Mr Obama is charging us for his trouser press, we want to know.’5

The Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, singling out Britain for attack after a disputed election, used the scandal as evidence of corruption in Western countries preying on Iran ‘like wolves’. The Zimbabwe Herald, mouthpiece of Robert Mugabe, suggested that Zimbabwean politicians needed higher salaries lest they be tempted into corrupt practices like British MPs. And politicians in the Turks and Caicos, a dependent territory in the Caribbean, asked how the British dared to suspend their constitution, on grounds of alleged corruption, in the light of what was happening in their own Parliament – and what kind of example was that?

At home it was like the start of the hunting season, with MPs as the quarry. Not just a few, but a substantial number of them – at first 100, then 200, and in the end at least a half – were named and shamed and vilified as never before, at least since the 18th century. There were so many of them that total honesty was seen as an exception. In drawing up lists it saved time to single out the saints rather than the sinners – the frugal minority who had not abused their allowances or claimed second homes when they did not need them. These included Adam Afriyie (Conservative, Windsor), Anne Milton (Conservative, Guildford), Geoffrey Robinson (Labour, Coventry North West), Martin Salter (Labour, Reading West) and David Howarth (Liberal Democrat, Cambridge). Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North) earned a mention in despatches for having claimed only £4,513 in four years while his neighbour Margaret Moran (Luton South), who lived in the same street, claimed £74,904. It was especially good to see the millionaire Geoffrey Robinson on the saints’ list, after his earlier falling out with the Committee on Standards and Privileges. Overall the sinners were a majority, the saints a handful and the rest of the MPs in borderline territory between them.

I had long suspected, from my time on Standards and Privileges, that many MPs were more concerned with their privileges than their standards. This seemed to be confirmed by some of the arithmetic. There was now a league table of MPs’ costs, ranging from the bargain basement Philip Hollobone (Conservative, Kettering) to the top-of-the-line, gold-plated and ultra de luxe Eric Joyce (Labour, Falkirk). Tom Levitt, the Labour MP for High Peak, who had served with me on the Committee, was the eighth most expensive Member in that particular pecking order. He had claimed £8,013.77 to refit the bathroom of his London home, and even £16.50 for a Remembrance Day wreath. The wreath was claimed in error, he said. The bathroom was a necessary expense. And he accused the Telegraph of conniving in gutter journalism.

It was noted that across the Commons, but chiefly within the two main parties, there was a pattern in all of this state-funded extravagance. The highest claimants of the Alternative Costs Allowance were also the MPs most obedient to the bidding of the whips. There was nothing they wouldn’t claim for or, when the division bell sounded, vote for. They would dutifully troop through the lobbies and pocket their tax-free allowances. The independent-minded tended to claim far less. Dennis Skinner was notably frugal. Yet some of the offenders on the Tory side were long-serving Members with reputations, until these scandals broke, as respected and effective constituency MPs. They were also country gentlemen of the old school who lived in considerable style. And theirs were the claims that kept the people talking and the cartoonists working overtime. The Telegraph’s Matt was in a particularly rich vein of form. The moat was just the start of it.

Anthony Steen was the Conservative Member for Totnes. He had been a diligent constituency MP since 1983, with a reputation for endearing battiness, which he advertised on his website. He was best known for intervening at Prime Minister’s Question Time to invite the occupant of Number Ten to visit his cockle fishers in South Devon. Cockle fishers never had a more devoted champion. In due course he might well have been honoured as a knight of the shires – it used to happen in an MP’s sixth term – but events got in the way. I rather liked him. The endearing battiness was genuine. He seemed every inch a character out of Gilbert and Sullivan: so much so that he once persuaded me to initiate a debate on Arts Council funding for the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company. It turned out that the House, from the Speaker on down, had a passion for light opera. Anthony Steen had an office just down the corridor from mine during most of my time as an MP. It was grander, of course, but still just a single room in Dean’s Yard near Westminster Abbey. He lived in greater style in his constituency. Over four years he claimed £87,729 to maintain this country house as his second home. The costs included money to inspect 500 trees and to guard his shrubs from rabbits. He was an MP after all. And it would never do for an Honourable Member’s trees to fall down or his estate to be overrun by rabbits.

But his arrangements, when they became known, were anathema to his party’s leadership. David Cameron demanded that he stand down at the next election, which he duly agreed to do. He then gave a most extraordinary interview to the BBC which suggested that compliance was one thing but repentance was another. ‘I have done nothing criminal,’ he said, ‘and you know what it’s about? Jealousy. I have got a very, very large house. Some people say it looks like Balmoral, but it’s a merchant’s house from the 19th century. … You know what this reminds me of? An episode of Coronation Street. This is a kangaroo court.’ He was then required to apologise and to remain silent on the issue, upon pain of expulsion from the party. The Conservatives were striving to shed their patrician image, and the exposure of the Toff of Totnes did not suit their electoral strategy.

Nor did the expenses of Sir John Butterfill, whose modest flat in his Bournemouth constituency was claimed as his main home. That left him free to designate as his second home, partly funded by the taxpayer, a six-bedroom mansion near Woking. The taxpayers’ subsidy for this included £17,000 for servants’ quarters, for grandees need servants much as ducks need ponds; and we shall arrive at the duck pond shortly. Sir John eventually sold the big house for a profit of £600,000. But by then he declared it to the Revenue as his main home, which was a common practice among MPs, so it was not liable to capital gains tax. Among the many instances of flipping and switching this was the one that, when exposed, required the greatest payback, of £60,000, to the taxman. David Cameron was not amused by these arrangements. ‘The lack of common sense and reasonableness has been shocking,’ he said. They suggested that his lot were at it as much as the other lot; and that his rebranding of the party still had some way to go.

The case of Sir Peter Viggers was an even greater embarrassment to the Tories and gift to the cartoonists. Sir Peter was the long-serving MP for Gosport in Hampshire. I had known him in the Commons as an eloquent champion of the military hospitals, which were threatened and eventually closed by successive governments just when the armed services most sorely needed them. But the naval hospital in his constituency was not his only water-related interest. He had also claimed £1,645 for a ‘pond feature’ which turned out to be a floating duck island on his Hampshire estate. It was a considerable construction, this duck island: a five-foot edifice designed on the lines of an 18th-century mansion in Stockholm. The ducks never had it so grand. The Fees Office, in a rare display of austerity, had actually refused to pay for it. But the duck island replaced the moat as the most striking symbol of parliamentary excess.

‘What the hell’s a duck island?’ asked an exasperated David Cameron. And Sir Peter too was required to stand down at the next election.

At this point, because it was a British revolution, the British press went quackers. Never mind the more serious cases of outright fraud and embezzlement: as far as the headlines were concerned it was the trivia that took wing and did the damage. There were features about duck farms, duck islands, duck houses and every recorded species of the bird: mallards, teals, mandarins, shovelers and 158 other varieties. Experts were found who questioned the usefulness of duck houses or islands as a protection against foxes; it turned out that foxes