11,51 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Martyn Murray was finding modern life, with all its restrictions and controls, suffocating. Following years of soul-searching, his father's death triggered him into opening the old logbooks and charts to retrace the sailing trips they had once shared together. He determined to revisit those waters and bring home the freedom of the seas. Falling in love with an old ketch in Ireland, he bought and restored her enough to sail back to Scotland. Over the next two summers he cruised Scotland's Western Isles, with one goal: to reach St Kilda – the remotest part of the British Isles, 40 miles from the Outer Hebrides. During his cruising he considered the islanders and their sense of freedom – often restricted by absentee landlords and officialdom. He railed against bureaucracy and commercial enterprise restricting the yachtsman's ability to roam free. For parts of his journey he was joined by the beguiling Kyla; a rare, independent spirit who both excited and frustrated Martyn. But much of Martyn's voyaging was undertaken alone, encountering a variety of places, situations and characters along the way. He attempted his long-awaited sail out to St Kilda through the teeth of a storm, believing that achieving this feat would bring him the freedom and clarity that he craved. What he came up against was far more testing and turbulent than the tides and gales of the North Atlantic. As he sailed back to the mainland things fell into place: a sense of achievement in completing the arduous voyage alone, but – most of all – an understanding of who he is, clarity on his relationship with Kyla and a real sense of his own freedom.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

A

WILD

Call

Martyn Murray

The real lives of sporting heroes on, in & under the water

Also in this series…

Sailing Around Britiam

by Kim C. Sturgess

A weekend sailor’s voyage in 50 day sails

Last Voyages

by Nicholas Gray

Looking back at the lives and tragic loss of some remarkable and well-known sailors

The First Indian

by Dilip Donde

The story of the first Indian solo circumnavigation under sail

Golden Lily

by Lijia Xu

The fascinating autobiography from Asia’s first dinghy sailing gold medallist

more to follow

Published in 2017 by Fernhurst Books Limited

62 Brandon Parade, Holly Walk, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 4JE, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 1926 337488 | www.fernhurstbooks.com

Copyright © 2017 Martyn Murray

Martyn Murray has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this Work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a license issued by The Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781912177028 (paperback)

eISBN 9781912177318 (ebook)

Mobi ISBN 9781912177325 (Mobi)

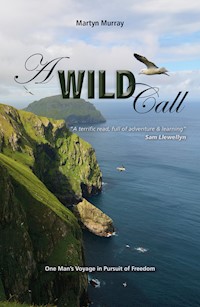

Front cover photograph: Birds flying above the ocean in St Kilda, UNESCO

Heritage Site, Scotland © Michele D’Amico supersky 77

Back cover photograph: Martyn Murray’s yacht, Molio, moored at St Kilda

© Martyn Murray

Designed & typeset by Rachel Atkins

For my parents

Greer and Wendy

With love and gratitude

For what avail the plough or sail,

Or land or life, if freedom fail?

Boston

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Contents

Preface

Part One

Chapter 1 Wild Boat Chase

Chapter 2 Dog Watch

Chapter 3 Did We Mean To Go To Sea?

Chapter 4 Fatal Flaw

Chapter 5 In The Wake of Saints

Part Two

Chapter 6 Glorious Day of Salvage

Chapter 7 The Sea Gypsy

Chapter 8 Molio’s Cave

Chapter 9 Mull of Kintyre

Chapter 10 Fiddler’s Green

Chapter 11 Ring of Bright Bubbles

Chapter 12 Stormbound

Chapter 13 Wild Mountain Thyme

Part Three

Chapter 14 Cup and Ring

Chapter 15 Wolf Island

Chapter 16 Isle of The Great Women

Chapter 17 Battle of Dreams

Chapter 18 The Dark Laird

Chapter 19 Piloting a Craft Called Freedom

Chapter 20 Flight of The Fulmar

Chapter 21 Abode of Ancestors

Chapter 22 Running Free

Notes and Sources

Glossary of Nautical Terms

Preface

In Scotland, whisky is a sacred drink. Amber as the life oozing from an old Caledonian pine, acrid as the smoke drifting down a ghost-filled glen, subtle as the twilight on a Hebridean shore. One swallow warms your heart like the first kiss on a long winter’s night; two swallows still the raging torrents of your mind as mountain waters in the slow deeps of a highland pool where gravid salmon lie; three swallows awaken your imprisoned soul and a longing for the old way, the merry way, and the chance to live free. Raising your glass is a custom older than the nation. It summons a bygone glory, seals a lifelong pact and etches forever a shared moment on the long journey home. The last thing my father said to me was: “Come on over Martyn…we’ll have a dram together.”

I packed my bags and drove over the next morning, but Dad had gone on ahead of me. So I raised my glass alone that night and as I took the third swallow a conversation began. Sailing was our shared passion, our common language. It was what we yearned for when trapped in a dull meeting or stuck in frustrated traffic. Our family boat, Primrose, bore no resemblance to the designer craft that pack marinas today; she was a working Cornish vessel from the 1890s, a wooden-planked, heavy-beamed, deep-keeled, gaff-rigged cutter with a tree trunk for a mast. She carried a press of tanned canvas in a stiff breeze, leaning sedately with the weight of wind yet lifting to the surge of sea, bow-sprit thrust forward over the waves. In my imagination her character matched those of my father and mother: like my father, load-bearing and warm hearted, dependable as Scottish oak; and like my mother, brave as the first English primrose and sunny as the spring itself. My brothers and I relished the daily fare of maritime adventure, one day exploring islands or anchorages, the next hunting for lobsters and shellfish, and the next inhaling the curiosity of seaside shops with their racks of comics and trays of sweets. It introduced a wild but disciplined freedom to our urban lives which I didn’t stop to think about at the time.

Glass in hand I walked over to the bookcase in the hall. One of the shelves was packed with my father’s favourite sailing books. I chose half a dozen and took them up to bed. The margins were filled with hand-written notes in his familiar tight longhand that few could read, save my mother and the pharmacist who had received countless scrawled prescriptions from his surgery. I stayed up late that night engrossed by the world of sailing in a bygone age. Time passed in a quiet routine: by day I went for long walks and chatted to Mum, in the evenings I went to bed early and read about sailing. On one of those evenings, I began to realise that something in those books was speaking to me. Dissatisfaction with my life had whispered in my ear for years and recently had grown to a shout. I’d taken time off to push out in different directions, looking for new sources of inspiration, but it hadn’t helped. In fact the more I tried to deal with it, the worse it had become. I felt trapped in my adult skin. Somewhere I had taken a wrong turn.

I kept coming back to one book, Dream Ships by Maurice Griffiths. It had a blue woven cover and well-thumbed pages filled with descriptions of the author’s favourite small craft illustrated by sketches of their construction, deck layouts and accommodation. I marvelled at their swept lines and cosy cabins, imagined myself hauling up the sails, making voyages to distant lands and tying up at the quay in a foreign harbour. An idea began to form, strengthening as each day went by, of finding my own dream boat, bringing her home to Scotland and preparing her for a voyage to St Kilda, that tight cluster of rocky isles lying far out in the Atlantic Ocean beyond the sheltering wall of the Hebrides, where the roar of surf mingles with the seabirds’ cry, the sea mist rises to the falling smirr, and what lies beyond enters freely within. Even then at the first inkling I sensed that a passage to St Kilda would have the power to change my life. I stayed for three weeks and by the time I left, I knew exactly what I wanted. It was the sweetest dram I’ve ever had.

Primrose, our family Falmouth Quay Punt, anchored off Ormidale Lodge in 1958.

Part One

Chapter 1

Wild Boat Chase

“She’s pissing out water like an old boot,” said a voice from a neighbouring boat on the pontoon causing me to look up in alarm.

“What?” I yelped hoping he was just a novice, perhaps noticing pools of rainwater collecting in the folded tarp and cascading off the algae-stained deck whenever the boat rocked.

A pair of blue eyes appraised me from the cockpit of an ocean-going yacht, taking in my office shoes and mental disarray. The easy confidence of the long distance sailor oozed from every one of his salty pores. “The bilge pump is on night and day; ergo, she’s leaking from somewhere.” He spoke with an imperious Oxford drawl.

Could this abandoned lady have a fatal flaw? I eyed her over again. Teak decks swept back from a high business-like bow, dividing to pass either side of the central cabin with its eight ship’s portholes followed by a roomy cockpit where I now stood in dripping jersey, before merging again at the aft deck, which ended in a counter stern with long overhang. Rigging descended on all sides from the tops of the main and mizzen masts to the outer fastenings of the wooden hull. Her classic lines, penned a lifetime ago by Fred Shepherd the doyen of pre-war designers, must have captured many an owner’s heart. Masts and spars were painted white not so much to match the topsides, I thought, as to protect against the tropical sun. She was a nomad all right, with her sheets, fairleads, winches and cleats ready for action on any of the seven seas, and every bit as sturdy as those on my neighbour’s boat. But she was a ragged Nomad, in truth more of a stricken refugee. It would be madness to take her on. Yet I needed her every bit as much as she needed a new owner. She could turn the tide in my life. I’d felt it the moment I set eyes on her. That tide was fast ebbing away and as my creative freedom choked off, so my spirit died. All my efforts to wrest back control and take command of my life again had come to nothing. It was as if I was caught in my dreams by a faery’s spell, and unable to wake up. If there was a way to break that spell then this boat rocking back and forth at my feet could help me find it. I felt certain of it. The wild confidence that had brought me to that small bustling harbour on the edge of a great storm-filled ocean took hold again. “I can bring her back to life.”

He looked across the gap of oily estuarine water between us and behind the grey beard with its crown of white, like Hemingway’s in his later years, there could have been a smile. “Shame to see a boat like that left to rot.”

I eyed the green algae and dirty deck sensing the hours of work and endless expense. The sky seemed to darken again. And there was something else nagging away. “She may not be so popular back home.”

He looked over once more, one eyebrow ever so slightly raised. I felt the challenge but wasn’t ready to meet it. Instead I busied myself with checking deck gear and making notes. I tried to forget Papa Hemingway. But you couldn’t face that penetrating gaze and pretend you hadn’t noticed. Looking back, I see myself standing at a gateway: in one direction business as usual, in the other a threshold to be crossed and the beginning of a journey. Not just any journey but a rite of passage that was long overdue. It was something I had missed as a teenager and again in my twenties, and again and again thereafter. There it was, right in front of me one more time. I clambered down the rickety ladder to continue my inspection in the main saloon. I inhaled the familiar damp smell of wooden boat. Rot, I thought, I bloody hope not.

Dim light pushed its way through opaque plastic fillers that blocked the original glass portholes. Their bronze surrounds were matted with verdigris. I switched on my torch. Mahogany furnishings glowed golden red under the beam, interspersed with cream panelling on the bulkheads. The arch of the coachroof above matched the curve of the bunks on either side. Immediately to my left was the galley with twin sinks next to a gas cooker; to the right a chart table with some ageing navigation equipment. Above it was a lovely brass clock and next to that a chromed barometer, cheap and rusting, which didn’t seem to fit. A photograph was taped to the foot of the starboard bunk showing her racing in the Caribbean off Antigua, sails taut, decks scrubbed, crew grinning. Beyond was a locker stuffed full of bulging sail bags; the heads opposite gave just enough room for a Baby Blake toilet and a small sink. Further forward was a double fo’c’sle bunk narrowing to the forepeak, now jammed with extra sails and surplus gear. It was like stepping into the 1930s. Spartan, sturdy yet intimate. An exception to the period was a collection of music cassettes in two long racks above the bunks comprising mostly jazz and blues albums.

Tattered? Yes. Tired? Obviously. Unloved? I didn’t think so. She was deserted now but someone had loved this boat. He’d left his clothes in a seaman’s bag, his letters under the navigation table and some tinned food in a locker by the galley. One day he had walked away from his life aboard and apparently vanished. I began to inspect each part of the boat systematically. Much of the visible damage was superficial stained cushions, rusted cooker, mildewed paintwork, broken hinges, missing catches and corroded electrics. What I needed to know was whether the dishevelled gear and unknown years of neglect concealed anything more sinister. Had the owner come across an insurmountable defect and given up, or had life simply intervened to separate man and boat? I piled cushions to one side and opened up the hatches under the port bunk. As I did there was a click and gurgle from below, followed by the splash of water streaming into Cork Harbour.

Under the bunks were plastic boxes with tools, engine spares, shackles, screws, reels of electrical wire, fillers, paint and all kinds of other chandlery. I pulled them out one by one. The contents were in an awful state – rusted, discoloured, damp and broken – but the planking underneath looked fine. I spotted a smudged brown line running along the topmost plank. It took a few moments for the penny to drop: it was a waterline, an inner, rusty waterline. The boat must have been half full of water. I touched the line with my finger: it smudged. Half full of sea water and not so long ago; that would explain the state of her gear. Out of curiosity I checked the seacock next to the double sink. It was jammed open. If she’d filled just a little more, seawater would have flowed back along the drain outlet, welled up inside the sink and over-flowed into the cabin taking the boat under in a few hours. It explained the only new things on the boat: an orange extension lead looping into the cabin from the pontoon connected to a powerful battery charger, now humming away on the pilot berth, hooked up to a lorry battery that connected to the bilge pump. I unscrewed the plastic caps of the battery to check the electrolyte level: the cells were dry. It must have been left to charge continuously. I emerged from below with a frown. At the far end of the pontoon, four little penguins frowned back. I was so preoccupied I almost overlooked them. They should have been off the coast of Chile; I’d no idea what they were doing here. As I looked, they huddled together like naughty school boys playing truant. The cloud of worry dispersed and I began chuckling.

Papa Hemingway was up the mainmast working on the VHF aerial from the safety of a crow’s nest. I walked over to take a look at his boat. She was built for the deep ocean with a heavy fibreglass hull. An eye of Horus was painted on the bows, its white pupil surrounded by a thick black iris as if the eye of some giant deity was staring across the ocean keeping a lookout for reefs and shoals. The teak deck was covered in heavy-duty cruising gear. A pair of massive anchors sat on wooden blocks that jutted out from the prow like railway sleepers; their chains snaked aft wrapped in old sailcloth and disappeared into deck boxes. A red lifeboat was secured in-between, with a spring release mechanism for emergency deployment. Behind that were a deep working cockpit with tiller steering and an aft deck with wind turbine and self-steering vane. A massive rudder hung on the transom.

I waited as Papa climbed down the mast steps and made his way to the cockpit. “Some boat you have here,” I remarked. “She looks as if she could go anywhere.”

He scrutinised me again, slow and easy, like an African hunter gauging his quarry lying wounded in a thicket.

“We’ve been around.”

I was unsure if he meant round the world but before I could find out, a spark came to his eye, “How about that wooden ketch? She needs someone to look after her.”

I looked back at the boat. There was a stream of water gushing from an outlet on the side. “She’s run down but the basics look good. I’ll need an expert’s opinion on that leak.”

“I’m on my way tomorrow or I’d give you a hand. I’ve been hanging about for a month working on this girl’s gearbox,” he patted the cabin roof. “It packed up in Horta. The mechanic here helped rebuild it. He’s a good handyman. That’s his boat.” He indicated a large steel ketch further along the pontoon.

“Where are you heading?” I asked.

“Next port is Porto Santo. I’m joining up with friends, then we sail in convoy to Volos.”

“Is that home?”

He shook his head. “The sea and my boat are home.” In another person it might have sounded grandiose. “Every long-distance sailor is my friend. If you join in,” he tilted his head back and observed me closely, bearded jaw thrust forward, eyes glinting under almost closed lids, as if daring me into some lethal schoolboy challenge, “you’ll be part of the closest community in the world. It’s like nothing else. It’s the essence of freedom.”

He stepped on to the pontoon, called a gruff “good luck” and walked off towards the marina. I watched him climb the gangway and make his way to the road. He had found freedom, but only by dedicating his life to the seven seas. I looked again at the wooden ketch rocking gently by the pontoon, still attached to land by its orange power line, the umbilical cord that kept her afloat. She was the boat of my dreams. But I didn’t plan on taking her to Tahiti, at least not yet. First I wanted to find freedom at home.

In the late 60s and early 70s, dreams abounded. It was not unknown for an office clerk to walk into a city boutique, gear up with kaftan, beads and a ‘This is the first day of the rest of your life’ badge, dump his suit in a dustbin and join a bunch of like-minded drop-outs in a commune. There was eagerness in the post-war generation to explore new ways of living and enough slack in society to let it happen. People were less ambitious and the state was more relaxed. Traffic control was perfunctory, crowds didn’t alarm the authorities, mass surveillance was non-existent, marijuana and psychedelic drugs were tolerated, there was less intrusion all round. It gave people an opportunity to express themselves in their own way; as a result there was room to dream and Great Britain was a creative powerhouse. My first dream came along whilst I was studying zoology at Edinburgh University, commuting from a derelict cottage in a roofless sports car. It struck home like a vision of St John the Divine. I would study the lives of individual elephants in Africa. Back then if you had a good idea, universities could provide funding for a personal PhD study.

Pretty soon I was immersed in the life of an African field biologist, not with elephants as it happened, but impala with their female gang society controlled by mob-boss males. Walking through the woods on foot brought me into close contact with the wild animals which buzzed with spiritual presence. As the days and months went by, the hidden rhythms of the bush revealed themselves bringing their own questions. Why did trees flush green at the driest time of the year? What drives the long-distance migration of wildebeest? Why did the moon trigger the rutting of impala males? As I walked quietly along the animal paths my mind sought for answers, flicking back and forth over the mental terrain just as my eyes looked for wildlife, darting back and forth over my surroundings. It was like living in an enchanted forest but one inhabited by Africa’s megafauna where new discoveries in Darwin’s theory of natural selection took the place of an infallible magic mirror.

I didn’t pay much attention to the changes going on in Britain, just took care to avoid jobs that might box me in. I moved to conservation, my next dream, choosing to operate as a freelance consultant. It meant hanging on to a thin thread of work but it took me to remote places, introduced me to rural communities with their unfailing dignity, generosity and ingenuity, and gave me back part of the year to follow my own interests. When I did finally stop to look around in the early 2000s, I didn’t like what I saw. Surveillance cameras were popping up like mushrooms on a moist day in autumn; crowd control was paramilitary; robotic answering systems turned enquiries by phone into an ordeal; companies snared personal information on the web; the work place was permeated by systems-thinking; students were saddled with loans by an older generation that had enjoyed free education; and even the universities, once temples of free-thinking, had been subverted by the need for corporate funding, or so it seemed to me. I noticed that those starting out in life had less opportunity to express their real selves, to hang out with like-minded pals and dream the good dreams the ones that could be hammered into life, the ones that set you free. But then I had to admit, I was out of touch.

There was something else I had to admit. I wasn’t fired up by my own work anymore. Hunting down solutions to the declining wildlife of Africa and Asia had been an amazing adventure that had stretched my creativity. But it had begun to take on the stale feel of the morning after party. We planned in boxes, made assessments on spreadsheets and reported in frameworks. Rote answers to prefabricated questions held sway over creative solutions and wider knowledge. I looked across at the wildlife organisations. Once proud and principled, they too had acquiesced to commercial ideals and ready-made solutions. Few of my work colleagues understood my passion for the wild which, if I were rash enough to show it, was usually met with embarrassed silence or outright suspicion.

Everywhere I looked there was a chasm between people and nature. I knew it was the fundamental problem even as I did my best to ignore it. Back it would come time and again to taunt me, like some will-o’-the-wisp luring unwary travellers into the bottomless marshes. It was for that reason more than any other that I detested the corporate take-over of my profession. It had severed the vital connection with wildlife just where it should have been strongest. It was an impasse.

If I was stuck at work, it was no better at home. Being single and with my children at university, I was freer than at any time since my early twenties. Yet nothing happened on the romantic front; I just didn’t seem to connect to anybody. Instead of a new chapter opening up in my life, I was left on the side lines like an extra watching teammates play the all-important game. Flat, numb and puzzled, I was adrift in the mid-fifties doldrums. Until that is the sea began to call me.

The first boat I’d looked at was a Holman 28, big enough for two or three adults yet easily sailed singlehandedly. The Essex Marina was asking £7,500, making it by far the cheapest boat on offer. There was nobody in the small office so I walked down to the forest of masts which filled an inland pond surrounded by reed beds. It was connected to the open sea by a muddy east-coast creek that wound its way through the flat wetlands. As I stood wondering where to look first, the lively song of a reed warbler announced the arrival of spring. I set off along the first pontoon and soon found the Holman: she was tethered forlornly to a metal cleat, listing to one side, looking as worn out as the day itself. The price might have been low but it was hopelessly optimistic. The varnish on the coachroof wasn’t flaking, it had disappeared altogether. The coaming was broken, sails dirty, halyards frayed, deck paint cracked and the metal mast looked as though it had been scoured with Brillo pads. Even the ‘For Sale’ sign was bleached from months of sunlight and curled at the edges. I shook my head. It was a tired dream at best. Was this all that remained of my youthful hopes?

The owner of the marina walked across, reading my face before I’d even spoken. “Lovely boat the Holman but perhaps not what you’re after?”

“What I’m after is a boat with a soul,” I replied. He had the grace to smile. In the vague hope that he might know of a hidden classic looking for an owner, I filled him in on the details. “A wooden yacht, maybe something from the 1930s or earlier, a touch bigger than this one,” I nodded at the Holman, “with curved lines that mirror her own wave as she surges through the sea, one that I might just fall in love with.” I looked him in the eye wondering if he understood.

“I know what you want,” the owner gazed over the crowd of shining white hulls, “but I’ve nothing like that at the moment. If you give me a phone number I’ll let you know when something comes along.” He led the way back to his office. It seemed a waste to return home without seeing other boats, so I pressed him harder. “I’m down from Scotland. Are there any wooden boats in Essex that I could look at while I’m here?”

He shook his head, but as I was getting into my car he had a change of heart. “If you drive down to the Container Port in London Docks, there’s an old yacht lying in a siding. She might do you.” I checked my watch. There was just time.

She took a bit of finding, but just before dark I spotted a tall mast and pulled up alongside a decrepit wharf. A stack of containers was rusting on the far pier, some nondescript tubs lay in the oily water below and an old motor boat lay semi-submerged along one of the side walls. Iwonda was moored on the nearside, varnished coamings and canary yellow hull brightening up her surroundings like a spring flower in a bombsite. I climbed down a ladder and stepped on board. She barely stirred. In front of me was a wide cockpit half covered by a faded tent. I peered underneath. Two wooden doors led into the main cabin, one to port and the other to starboard. I chose the one to star-board and crawled under the tent to grasp the bronze handle. It turned and the door opened easily. Inside was a sumptuous saloon with dark red divans and acres of polished wood. A steel centreboard was artfully integrated with the central mahogany table, its wings folded down. A solid fuel stove stood at one end. She rocked gently as I moved causing water in the bilges to slosh about and spread a putrid whiff of the dock. Did her opulent clothing mask a diseased bowel?

Back on the wharf I met up with some sea scouts who were living on a Brixham Trawler moored in the adjacent dock. “Any idea who the owner of Iwonda might be?” I asked. There were some shrugs and head shakes.

One young sailor from north of the border was staring at me intently. He glanced down at the boat and then back at me. “She’s like a greyhound in a kennel. Ken what I’m saying?” He spoke in a high-pitched voice on the edge of panic and I recognised the anguish of a fellow exile. He came forward a few more steps until his face was only inches from my own. “Someone’s got to free her.” His breath smelt as sour as the harbour but he held my eye in an unforgiving stare for some seconds, daring me to deny it, before turning abruptly to follow the others.

Iwonda has made a conquest there, I thought. The light was going so I took a few more photos from the pier before setting off for home. There was plenty of time to mull over possibilities on the long drive north. That trawler lad might have taken a cheap shot to try and get me hooked but there was nothing phony about his feelings for the beautiful craft lying bound to iron rings in a dirty wharf. Surrounded by walls, she was hidden from sight even by the sharp-eyed river-craft folk. She should have been out in the east-coast estuaries amongst the wildfowl, reed beds and tidal banks. She needed an owner to love her, to wash her decks and light her oil lamps in the twilight. But there she was, alone in her cell, dirty, uncared for, slowly dying. Her fate hung in the balance.

Might I take a risk and free her? I could get her out of that sewer for a start, clean her up and make a proper assessment. There would be much to take on. The deck was rough looking and might be rotten. She was leaking below the waterline. I thought about the options as the miles rolled by. Somewhere near Scotch Corner I saw that the real question was whether Iwonda would be a safe boat at sea. I mentioned the boat to my brother and he put the word round the local yacht club. A friend of the previous owner rang me out of the blue.

“Did you know that Iwonda was kept in the harbour at Dunbar?” he asked.

“What here on the Forth?”

“Aye, right on your doorstep. What a bonnie boat. We’d sail her to Bass Rock and back on an evening. She was fast. Never took us more than three or four hours. It could be a bit wet mind you. Her bows are that low, she’d take the seas on the foredeck. Nothing to worry about, they just washed o’er the side.” He paused a moment. “Mind you,” and he paused again, briefly but long enough to get my full attention, “she capsized once in a squall off the Bass. Came up all right but it was a bad moment.”

I wondered no more. With her flat bottom and centreboard, she was a boat for the east coast creeks and inlets of England. I hoped the right person would come along and loose her from the iron rings, but she was not built for the deep waters and gusting winds of the west of Scotland. I started searching again. The next boat I went to see was the antithesis of Iwonda – an immaculate 43 foot Morgan Giles sloop with teak planks that were copper fastened to oak frames and a deep keel. Yet something didn’t feel right. The boat lacked warmth.

So it went all summer, as I visited one boat after another. Either I feared some ghastly malady hiding beneath charming looks or else, though sound in deck and hull, the boat left me unmoved. It was a bit like speed dating I imagined. None of the candidates lived up to my dream. Eventually I grew tired of it. My success in the world of boating was proving no better than it was in the world of romance. Soon I was working overseas on a demanding consultancy. I could see that I didn’t really need a boat. It would just be a worry when I was called away. My life was fine really. Midlife crisis be damned, it had just been a bit of a wobble.

“Have you found a mermaid to keep you warm at night?” asked Neil who had rung for some craic. He had been my neighbour at a research station in the heart of the African bush. We helped each other out from time to time but more often than not it was he who pulled me out the mud, and, invariably, with some Irish anecdote to lighten things up.

“Not one that hangs around,” I replied.

“But she’s out there waiting for you; that’s for sure.” I grunted in a non-committal kind of way. Neil switched tack, “You’ll be having more luck with the boat hunting?”

“Hah!” I snorted. “No woman, no boat. The gods have abandoned me.”

“Well there’s a thing all right. Tell you what. Why not try over here? There are some rare beauties in the creek – just waiting for a Scotsman to come by. Sure they’ve only seagulls for company. Come over now and I’ll show you.”

Irish boats. It got me thinking. I’d searched in Scotland and England and even glanced at the ads for boats on the Continent. For some reason I hadn’t looked in Ireland. But that was in the summer. It was November now and the triple combo of cold, wet and wind was enough to dissuade me from further boat hunting even if I had still been interested. On the other hand, southern Ireland sounded tropical compared to the east coast of Scotland. It would be good to have a break and there was no harm in idling around some of the marinas. Later that week I boarded the shuttle from Edinburgh to Cork. Neil was waiting for me in arrivals. Despite the years I recognised him immediately. Perhaps a bit balder on top but ramrod straight, head cocked to one side like an eager gundog, and with that same mischievous smile playing at the corners of his mouth which barely managed to quell the riot of Irish humour bubbling inside.

“How are you?” he greeted me.

“Ready to go,” I replied.

“Good man yourself! Come on then, I’ll show you the best places on our way back to my office. Tomorrow you can borrow the car and get stuck in.” He drove me down to Carrigaline passing through woods that were holding on to the colours of autumn. We passed the road that I would take the next day to search for boats along the Owenabue River, which ran down to Crosshaven, the original home of Irish sailing. “It’s packed full of yachts. I’ll put the word out amongst some sailing friends.” We turned north following a small road to the Cross River Ferry, which took us over to Carrigaloe. From there we drove along a country road to Fota Wildlife Park where Neil had his office and then on to his home.

Rosie greeted me at the front door with a hug. “Come in, come in. You’ll not mind the chaos.” I walked in feeling at once at home, just as I had back in Africa. Rosie had that enticing Irish mix, part mystic, part minx, leavened with a no-nonsense country charm and a talent for home-making. Later that evening, we went to their local. The music was grand and the lead singer, a wild redhead, reminded me of someone else, somebody I was trying to keep out of my thoughts. I felt her gaze for a moment as she looked in our direction.

Rosie leant over, “There you go Martyn, buy the girl a drink now.”

I laughed, which is what Rosie had wanted of course. “I’ve just met someone, actually, at a party in Edinburgh.”

“Well you’re a dark horse all right. So who is this girl?”

“Kyla.” I shook my head wondering how to describe her. “Tangled red hair like that one,” I glanced at the singer who was now halfway into an Irish ballad about a young maid and an untrustworthy soldier, and was singing as if she’d been there. “Green eyes that seem to see right through you. But whenever I get close, she sends me packing.” I shook my head again. “She’s a puzzle all right.”

“Neil, did you hear that? The boy is smitten.”

“Leave him be Rosie, he’s got more serious things on his mind than women.”

Rosie gave him a friendly shove. “What would you know about it, you eejit.”

Turning back to me she put her hand over my glass to stop me drinking, “Come on now Martyn, it’s not like you to be scared off by a few words.”

“I was driving down to England to see her. I was more than halfway, when she turned me back. Cut me dead.”

“Women can be right hard,” began Neil but stopped when he got a look from Rosie.

“Is that it?” asked Rosie. “I’ll let you into a little secret boyo. A woman may seem harsh at times, even very harsh and for no reason. But we have our reasons. And what we admire in a man is someone who is not put off. So don’t you be a sap now.”

“Maybe,” I nodded. “Maybe you’re right.”

“Rosie is usually right on these things,” said Neil, “but Martyn aren’t your forgetting something?”

“What’s that?” I asked readying myself for a wisecrack.

“It’s your round!”

Next morning Neil roused me at 06:30 with a mug of Irish tea and a bowl of porridge. I dropped him at the wildlife park, crossed the ferry and drove on to Carrigaline and the Owenabue River. I slowed to enjoy its tree-lined meanderings and eyed up the boats on their moorings. Part way along was a lagoon with a number of fine yachts. In 1589 Sir Francis Drake hid a squadron of five ships there to escape the Spanish fleet. He had been chased across the Celtic Sea and managed to enter the great natural harbour of Cork ahead of the Spaniards. Once through the tight narrows, he’d turned hard to port and sailed up the Owenabue rounding two sharp doglegs to moor in the lagoon. The masts of his ships would have been shielded from view by the tall woods and Corribiny Hill but it was still a gamble. The Spanish ships did pursue, entering Cork harbour and sailing round its extensive shores but they never found the English ships. Looking at the hidden pool, speckled now with raindrops and fallen leaves, I thought of Drake concealed on the hilltop watching the Spanish ships as they hunted for him. What a shout he must have given when they finally gave up and sailed out of the narrows.

A jingle from my cell phone brought me back to the present. It was Neil. “Get along to Feste Marina, now – it’s near the yacht club. Ask for Torstein. He’s the Norwegian owner. My friends on Great Island say he had a wooden ketch for sale. It’s a while back, mind you, but you never know.” He hung up, in a hurry to deal with the next wildlife emergency – some escaped penguins.

A mile down the road I found the sign and turned into the boatyard. A stack of yachts were out on the hard in preparation for winter, propped up on galvanised boat cradles. Behind them was a makeshift workshop. I walked over, catching glimpses of the water between the boats. The creek was three or four hundred yards wide at this point with a line of trees on the far bank. A number of yachts were tied alongside the pontoons out in front, taking advantage of the mild Irish autumn to enjoy some late sailing. Nobody was sailing today. There was a biting easterly wind bringing wintry showers. I knocked on the shed door and then shoved it open. Inside a man in overalls was busy welding; he broke off for a second to point me at a small office in the far corner. I walked over and went through the open door. A large man sat hunched over a metal desk, like a bear with a sore head, staring at some figures. He was wearing a heavy biker’s jacket.

“Are you Torstein by any chance?” I asked, anticipating another dead end in my wild boat chase.

He looked up revealing a large drooping handlebar moustache beneath two smaller handlebars that served as eyebrows. “Who are you?” he growled in a thick Norwegian accent.

The thought of the warm café that Rosie had mentioned crossed my mind. It was a lot more inviting that talking to this terse Norseman in his freezing office. “My name’s Martyn. I’m looking for a yacht. What I’m really after is a wooden boat.”

The Viking’s gaze had diverted back down to the page of accounts which seemed to hold a particular fascination for him. “So what do you want from me?”

The thought of coffee crossed my mind again. I pictured a window seat next to an open fire with a view of boats coming and going. “I’m staying with friends in Midleton,” I replied. “Neil works at Fota Wildlife Park; one of his friends said you might have a wooden ketch for sale.”

“Fota! So tell your friend we’ve got some of his penguins here.” He stared at me again without blinking but I noticed the briefest twinkle in his eye. Then he fished about in a drawer and chucked over some keys. “He’s on the first pontoon, on the left, red covers, you can’t miss him.” And with that he buried his head in the accounts again. Despite every effort, I felt my heartbeat quicken.

I strolled across the yard going deliberately slowly, reminding myself that I was just a tourist. Passing between the opulent rows of fibreglass boats I came to the marina gate; beyond were half a dozen pontoons with an assortment of yachts and motorboats lying alongside. I walked down the gangway to the nearest pontoon watching my feet as the wood was slippery in the rain. Glancing left I found her almost at my feet. Like a dream straight from Maurice Griffiths’s book: thirty-six feet of ocean-going wooden yacht, two-masted with a powerful bowsprit, sweeping decks well raised above the sea, a graceful counter stern, deep cockpit and long cabin. She was weatherworn but to my eyes the epitome of sea magic. My curious smile widened quickly into a broad grin. The search was over.

Back in the office, I gleaned a few more facts from the Norseman. The owner’s name was Barry. He’d sailed over from the Caribbean some time ago and left the ketch at a nearby yard. Then he’d departed for the Emirates. She’d sat on land for two years or perhaps more, seemingly abandoned and then been moved to the marina and put on sale. She’d been there for another two years. There was a cousin somewhere around who looked after things. I gave the Viking my card with an email address and asked him to pass it on. He pushed it to one side, grunted something, and went back to his accounts.

“Jeannie Mac! but you don’t waste time,” exclaimed Neil a few weeks later as I handed him a pint of Murphy’s. “Mind now – she’ll give you nothing but trouble.” We had retired to Cronin’s in Crosshaven and I was telling him about my negotiations with the boat’s owner. Emails had been flying back and forth from Scotland to the Emirates. He’d wanted £42,000 for her. I pointed out that she had sunk at her mooring and looked semi-derelict. In the end, he’d dropped to £28,000 and agreed to a survey. I’d found the best wooden-boat specialist in England and asked him to meet me in Crosshaven. He’d been examining the boat all day, pricking each timber to test for rot, checking for signs of structural damage or bodged repair work, and assessing what life was left in the sails, rigging and electrics. His notebook was filling up with comments in a tight, spidery hand. “You must be mad now.” Neil looked genuinely concerned.

“Ah, but she’s a rare beauty. How can I pass her by?” My head was spinning with ideas about rescuing my dream boat and sailing her to Scotland. “I’ll have to get the price down. The owner knows the score. Nobody is buying wooden yachts. And if the surveyor finds any more problems… there’s bound to be more problems… he’ll drop the price.”

“I hear she was stood out the water for two years. The mast was lying on the fecking sod.”

“Willie told me he’d cut the rot and scarfed in a new piece of Yellow Fir.”

Neil nodded; he knew Willie’s reputation for repairing wooden boats. “And what if there’s more rot? What if you’re fecking about in the ocean and the bottom drops off?”

The door swung open and the surveyor walked in with the quick-eyed movement of a ferret, a nautical ferret at that I thought, with a single gold earring and a loose kit bag over one shoulder. I shifted along the bench to give him some room while Neil fetched him a pint from the bar, placing it carefully on the polished wooden table. The surveyor took a deep swallow.

“You’ve had a long day,” I declared.

He took another long pull which brought the level right down and wiped the foam from his beard. “What a lovely old girl,” he said.

“Now he’s looking just like the Cheshire Cat,” said Neil, eyeing my broad grin over his glass.

“I’ve been over every inch that’s accessible and as far as I can tell, she’s sound,” continued the surveyor. “The oak frames are strong and there’s no sign of rot in the planking. The strakes are made from Pitch Pine which is full of resin. That’s been protecting her. The teak deck is a bit worn but it should last another ten years. Mind you it will need some caulking. Structurally she’s sound as a bell. The mast and spars are true and the engine is almost new.” He took another draught of beer and paused briefly to flick through his notes. So far so good, I thought. “In other respects mind you, she’s in a deplorable condition. The sails and rigging are at the end of their working life. The electrics are corroded. The main switchbox is pretty much shot. There’s rust coming up from the keel bolts. There’s a gap between the deck and the sheer strake on one side. The toilet pump is jammed; so are the seacocks. The navigation instruments are old and unreliable. The whale pump isn’t working. The stove needs replacing and while you are at it, you should replace the gas piping. The soft furnishings are dilapidated. Pretty much everything is worn out.

“That sounds good but it doesn’t sound good,” I replied. It felt like I was on a roller coaster.

“There’s a saying,” the surveyor explained, “when it comes to valuation – one-third for the hull, one-third for the spars, sails and rigging, and one-third for the engine, instruments and other gear.”

By that reckoning, I reckoned she was one-third sound, one-third worn, and one third a mixture of new and deplorable. I scratched my head in puzzlement.

“Now that’s a marvellous equation, that is,” said Neil, “the yoke is half good and half bad.”

“If you can do some of the restoration work yourself,” said the surveyor, “it won’t be so bad.”

“I could give it a go,” I nodded “but where would I start?”

“Tell you what,” said the surveyor. “I’ll write out a programme for you with the things that need to be done right away and those that can be done over the next few years.”

“Thanks, that would be useful.” As I thought about it, the sun seemed to come out. “More than useful, that would be bloody marvellous,” I signalled to the bar for another round.

“Wait a minute,” said Neil. “How about the leaks? We don’t want him fecking drowned just when you’ve got him to open his pockets.”

“There’s a leak from the rudder mounting,” said the surveyor. “You can see the stains running down the hornbeam – it wants sorting but shouldn’t be difficult. One of the garboards needs re-caulking. I can’t see any big problems there. I would re-fasten all the planks just to be safe.”

“You think she’s up for long-distance cruising?” I asked.

“She’s a strong boat. She’d take you anywhere once you’ve seen to her, but don’t underestimate the work.”

I took a big breath. “So how about the price? What do you think she’s worth?”

The surveyor grimaced. “It’s hard to put a price on a boat like this. It’s as much about what someone is willing to pay as it is about the condition of the craft.” He took a deep pull from his second pint. “She’s got a great pedigree. She’s sound enough. But she’s rundown. The market for wooden boats is flat. I’d say anywhere between twenty and thirty thousand pounds.”

“I’d need to get her at the bottom end to afford her.” It felt as if I was looking over a cliff edge – a cliff made of tenners.

“I’ve got an old sailing barge,” said the surveyor. “Keep her in a creek next to my house in Essex. Wonderful old girl. She takes a bit of looking after, just like this boat will.” He smiled for the first time. “You’d have a lot of fun with her.”

True to his word, the surveyor wrote a report as thick as an old telephone book with pages of notes on the boat’s condition and a plan in each section for how to bring her back to cruising condition in affordable steps. I sent a copy to the owner with a note highlighting the more costly repair work needed. Barry sent it back unread with a covering note. “It’s £28,000 or nothing. You have to understand that this boat was my home for 3 years in the Caribbean. I sailed her across the Atlantic twice. I know exactly what she’s worth and I’m damned if I’ll let her go for a penny less. I’d rather pay the marina charges and sort her out myself when I get back.”

I went back over my savings again. They didn’t come close. It would be reckless to ask the bank for a loan given the unpredictable nature of my work. It all pointed to no deal. The problem was she had a name now, Molio. It was the affectionate name given to St Molaise by the people of Arran when he arrived from Ireland at the end of the sixth century to live the life of a hermit. And with her name came connection. Molio was not just a boat anymore. She was my passage to freedom. For all his dire warnings, Neil understood. When a man is trapped in a complicated world of work and commitments, freedom comes at a price. But it is surely a price worth paying. I made an appointment with the bank manager in my home town.

Neil Stronach and his daughter Sonia check out Molio in Crosshaven just before I concluded the deal to buy her.

A few months later, I met Barry on board Molio to make an inventory of gear. He was a friendly man, the type of sailor who would lend a hand if you were in a fix, or invite a party of guests on board for a meal in the evening. At the same time, he seemed restless with an eye on the next horizon. He’d brought over his new wife from the Emirates. It was perhaps the final act in exchanging one life for another. He didn’t want anything from the boat. He hardly wanted to touch her. He nodded at a large duffel bag on the bunk. “You’re about my size; hang onto the clothes if you like.” Later I would send a parcel of personal letters and photos to the Emirates, receiving in return papers and photos of Molio’s previous life with a video of her racing in the Antigua Classics. But for now, he wanted out. We went quickly over the inventory and retired to Cronin’s to sign the bill of sale. Neil and the Viking were already there as witnesses. We stopped business for a minute to share a glass. Then I wrote the cheque and handed it over. As I did, I noticed the look on the Viking’s face. He was incredulous. How could a Scotsman part with so much cash for a decaying wreck? But then, he didn’t know; this boat was the gift of a father to his son.

The Parts of a Ketch

Chapter 2

Dog Watch

Neil served up a large bowl of porridge overflowing with creamy milk while the rest of the house slept on. It had become part of the summer’s pleasant routine. He took Dusty, the family’s black Labrador, up the road to the field while I listened idly to the radio. The weather forecast promised a fine day with the possibility of thunder. Just three months from the purchase of Molio, I’d returned with a couple of months in hand to sort her out and sail back to Scotland. I looked again at the map of Ireland, my eyes tracing the south and west coasts. I was drawn to the romance of the Irish west coast, as I was to Scotland’s. If I was going to choose that way home, I had to be confident of my boat. In a storm, the giant seas rolling in from the Atlantic would create a confusion of the safe channels in amongst the coastal rocks and shoals. If caught out the only option, especially in driving rain and poor visibility, would be to get clear of the land and wait it out. Molio would have to withstand hours of pounding without complaint. The worst scenario would be the boat taking in so much water in heavy seas that I was forced to try for shelter in amongst the reefs.

Stuffing a pint of milk in my pack, I chucked it in the back of the rented car and set off for Feste Marina. A few minutes later I was savouring a mug of coffee in Molio’s saloon surrounded by tools, boxes of gear, floorboards and half-finished repairs. I jotted down some notes for the day’s work, wondering again how long it would take to ready Molio for the open sea.

My aim for the summer was simple enough: to restore boat and gear sufficiently for a trouble-free passage to Scotland while spending the minimum on her. But the following summer I had more ambitious plans. St Kilda was the furthest and most remote archipelago in the constellation of archipelagos that make up the Hebrides. For inshore sailors on the west of Scotland, it was the ultimate challenge. In a small way, it was their Everest. Sailing Molio to St Kilda single handed was my goal. The passage might have seemed trivial to Papa in his ocean-going yacht, protected by the all-seeing eye of Horus, but I was a long way from that level of competence. So it was a kind of initiation test, a way of proving myself. I knew my father would have approved; we had even talked about the possibility but never managed it.

As ship’s surgeon my father saw active duty on the HUNT-Class Destroyer, HMS Bleasdale, and the Fleet Minesweeper, HMS Plucky, in the Atlantic, North Sea, Mediterranean and the Far East, taking part in the Dieppe Raid, Normandy Landings and many other episodes of war. Whilst attached to a flotilla of Motor Torpedo Boats based at Felixstowe he met my mother, who was serving as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment and so began a wonderful love affair that lasted beyond their diamond anniversary. Like many others who took part and survived, he didn’t talk about the war, preferring instead to make the most of the peace that followed, a peace that he and a whole generation had fought for and bequeathed to us. He raised a family of boys with my mother and built a thriving GP practice in Ayrshire with his medical partners. A GP’s life was hard in those days with many nights of broken sleep to attend urgent and not so urgent calls and with most weekends foreshortened by surgeries. He found a respite from it all in his passion for the sea. He was never happier than when sailing a small yacht off the west coast of Scotland, preferably with family or friends for crew, but quite content on his own. He taught my brothers and me by example about boat handling, navigation and the art of cruising, and, just as importantly, how to keep a boat happy and safe.

Memory of the great struggle which overtook my father’s generation has receded with time, and in Britain we have become more or less passive recipients of that hard-won freedom. Yet I have a sense that the liberty they handed down is being eroded now by an enemy within. My children and their friends don’t appear to have as much freedom to choose their own style of living. Jobs are more tightly prescribed. Lifestyle options are fewer. The consequence of ‘time out’ is more frightening. And for those already in the swim, many share my unease over the increasing amount of intrusion into their lives. They protest at the ‘system’, yearn for escape from the pressure cooker, dream of being free as a bird. But despite well-fought rearguard actions against the worst excesses of regulation, incremental intrusions keep slipping past. Some time ago I began to suspect that freedom really was in retreat. I could see that the choices which defined life in the past – how to live, where to live and what to learn – were the very areas of life most likely to be prescribed today by economic pressure or government regulation. There might be a cloud of creative opportunity exploding on the web but I was by no means sure it would open the door to living free. Would tomorrow’s teenagers climb the wild Scottish Mountains solo on a whim, or sail in the outer isles with no intrusive contact from the outside world?