9,99 €

9,99 €

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

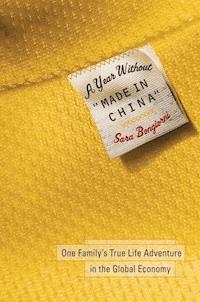

A Year Without "Made in China" provides you with a thought-provoking and thoroughly entertaining account of how the most populous nation on Earth influences almost every aspect of our daily lives. Drawing on her years as an award-winning journalist, author Sara Bongiorni fills this book with engaging stories and anecdotes of her family's attempt to outrun China's reach–by boycotting Chinese made products–and does a remarkable job of taking a decidedly big-picture issue and breaking it down to a personal level.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

4,7 (16 Bewertungen)

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE - Farewell, My Concubine

CHAPTER TWO - Red Shoes

CHAPTER THREE - Rise and China

CHAPTER FOUR - Manufacturing Dissent

CHAPTER FIVE - A Modest Proposal

CHAPTER SIX - Mothers of Invention

CHAPTER SEVEN - Summer of Discontent

CHAPTER EIGHT - Red Tide

CHAPTER NINE - China Dreams

CHAPTER TEN - Meltdown

CHAPTER ELEVEN - The China Season

CHAPTER TWELVE - Road’s End

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

INDEX

Copyright © 2007 by Sara Bongiorni. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada.

Wiley Bicentennial Logo: Richard J. Pacifico

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials.The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation.You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed by trademarks. In all instances where the author or publisher is aware of a claim, the product names appear in Initial Capital letters. Readers, however, should contact the appropriate companies for more complete information regarding trademarks and registration.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Bongiorni, Sara, 1964-

A year without “made in China” : one family’s true life adventure in the global economy / Sara Bongiorni.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-470-11613-5 (cloth)

1. Boycotts—United States—Case studies. 2. Consumers—United States—Attitudes. 3. Exports—China. 4. Globalization—Economic aspects—United States. I. Title.

HF1604.Z4U643 2007

382’.60951—dc22

2006101154

For my family, Kevin, Wes, Sofie, and Audrey

FOREWORD

China. A country with a population of more than 1.3 billion people. The most populous country in the world. And now its economy is no longer isolated from the rest of the world. Indeed, it is China, not Mexico, not Korea, not India, that most Americans think of when asked,Where do the goods we buy come from?

As the Chinese economy has grown it has come into direct competition with U.S. manufacturing firms. With low wages and government assistance, the Chinese manufacturing juggernaut has captured markets for goods previously made not just in the United States but in other countries as well.

The surging Chinese economy has created uncertainty, fear, and even anger about unfair competition. It has also become a major political issue as middle-class manufacturing jobs are being transferred overseas.

The image of China as the beast of the Far East is well entrenched. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the reality matches the popular perception. So, is China really the economic steamroller we think it is? Even more important, could we really live without Chinese goods? That is the question asked by Sara Bongiorni in her book, A Year Without “Made in China.”

So, what is the truth about China? The economic data are not as clear as the press would have us believe. Beginning in the early 1980s and accelerating in the 1990s the Chinese government stopped centrally controlling its economy. China began opening up its markets, and the flood of foreign investment into the country led to an enormous growth surge in the economy. By the end of 2006, China had one of the five largest economies in the world, and by one measure, called purchasing power parity, it was second only to the United States.

In the United States, we think that everything China makes is immediately sent here. Actually, that is not the case. China shipped about $290 billion in all types of goods to the United States in 2006. More than 11 percent of China’s output winds up in the United States. Only about one-quarter of all Chinese exports get sold in America. Still, that is a very large proportion, making the U.S. consumer critical to the well-being of the Chinese economy.

Chinese goods may not make up everything we buy, but they sure are a major portion. We import more than $2.2 trillion in goods from all over the world. About 15 percent comes from China and that is not a small amount. Compared to the size of the U.S. economy, though, it is. The U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2006 was more than $13.2 trillion and consumer spending exceeded $9.2 trillion.

It seems, then, that we should be able to live very easily without having to buy Chinese products. But that just may not be the case, especially for lower- or middle-income families. While the data appear to say that China is important but not critical, that is in relation to all the goods and services we get from the rest of the world. For the average American looking for clothes and less expensive manufactured goods, it is a different story. Many of the goods we do sell in this country are indeed “Made in China.”

And that gets us to the story. Is it at all possible to go for an entire year without buying something Chinese? Most likely yes, but you really have to look hard and even then you will probably fail. Many goods have components that are made in China but assembled elsewhere. Most manufacturers couldn’t care less where the component was initially produced. They only care that it is cheap and fits their needs. Competition is king and those with the lowest costs rule.

Essentially, A Year Without “Made in China” is about the reality of globalization. Actually, it is not really even about China but is a tale of how the world has changed and, more important, where the world economy is headed. Almost everyone’s standard of living is improved by being able to purchase less expensive products no matter where they are made. Our incomes go a lot further. Businesses can use the extra resources freed up by using the least expensive product to produce more at a lower cost as well.

For workers in those industries and firms that can no longer compete, though, their jobs have been lost. Would they be willing to buy fewer goods because the prices are higher in order to preserve their jobs? The answer is yes. But for the rest of us, we don’t want to pay more and we vote with our dollars. We buy cheaper products regardless of where they are produced. And for now at least, many of those goods come from China.

So living without foreign products may be an option, but it is not a very realistic one. In the 1950s, it was Made in Japan that worried our manufacturing firms. Now it is Made in China. In the future, it could be Made Somewhere Else.

—JOEL L. NAROFF President, Naroff Economic Advisors, Inc. Chief Economist, Commerce Bank

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people deserve special thanks for insights and suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript.

Debra Englander and Greg Friedman of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. guided me through the publishing process with good-humored expertise.

My agent, Theron Raines, gave generously of his time and experience in reading the chapters, fine-tuning my storytelling with a light touch, and encouraging me at every step.

My wonderful friend and fellow writer Renee Bacher Smith provided editing suggestions, publicity contacts and enthusiasm that made writing the book a joy. I could not have done it without her.

With characteristic kindness, my parents, Lois and Lars Hellberg, turned over their home to my family and me for two weeks so I would have a quiet place to write several chapters. My brothers and sisters-in-law, Mike Hellberg and Evanna Gleason and Dan Hellberg and Lauren Choi, provided help in many forms, including tracking China-related news for me and helping me prepare the final draft of the manuscript.

I would like to thank Danny Heitman, Maggie Heyn Richardson, and Michele Weldon for their suggestions on how to tell our story. Charles Richard and Barbara Clark provided essential early momentum for the book.

Friends old and new helped me in many ways. I would like to thank Cindy and Dominique Desmet, June and Mark Fabiani, Ed Smith, Hannah Smith, Chuck Jaffe, Sheelagh O’Leary, Mikel Moran, Shannon Kelly, Pamela Whiting, Caroline Kennedy Stone, Maribel Dietz, Jordan Kellman, Rick and Susan Moreland, Tara Jeanise, John Richardson, Carolyn Pione, Wayne Parent, Pietra Rivoli, Sarah Baird, Elise and Mike Decoteau, the Perkins and Kelly families, and Mukul and Lisa Verma.

Wes and Sofie Bongiorni were patient with me on days when I spent long hours at the computer. Audrey showed extraordinary consideration for a baby, sleeping for much of her first weeks of life while I made final tweaks and wrote the introduction.

Finally, I would like to thank my husband Kevin Bongiorni, who entertained our children for days on end so I could write, helped me recall key events, and generally took good sportsmanship to a new level. He provided much of the book’s most lively developments, simply by being himself.

INTRODUCTION

On January 1, 2005, my family embarked on a yearlong boycott of Chinese products. We wanted to see for ourselves what it would take in will power and ingenuity to live without the world’s fastest growing economy—and whether it could be world’s fastest growing economy—and whether it could be done at all. I knew China needed consumers like us to fire its economy, but did we need China, too?

We had no idea what we were up against. China is the world’s largest producer of televisions, DVD players, cell phones, shoes, clothing, lamps, and sports equipment. It makes roughly 95 percent of all the video games and holiday decorations imported into the United States and nearly 100 percent of the dolls and stuffed animals sold here—an inconvenient fact for a family like ours with small children.

Low wages, currency manipulation, and government subsidies help explain China’s place as the world’s top producer of consumer goods. So does the mind-boggling output of Chinese factories with more than 50,000 fast and energetic workers. As many as 2 million Americans have lost their jobs to Chinese competition, but we still can’t get enough of what China is selling. The trade deficit between China and the United States continues to set records; it jumped 25 percent to $201.6 billion in 2005, the year of our boycott.

Our bid to outrun China’s reach unfolded as a series of small human dramas. For me, boycotting China meant scrambling to keep my rebellious husband in line and disappointing my young son. Shopping trips for mundane items like birthday candles and shoes were grinding ordeals. Broken appliances brought mini crises. Friends and strangers alike had strong opinions about the boycott, and nobody was shy about telling us what they thought. Sometimes the boycott stung, but a lot of the time it was fun. It was, as I had hoped, an adventure.

It was something else, too. For years, I had started my day with the Wall Street Journal and a cup of coffee. I devoured stories about China. As a business reporter, I did my best to make sense of shifts in the global economy in the stories I wrote. But the truth is, China was more than 7,000 miles away—too distant to see or feel. The boycott made me rethink the distance between China and me. In pushing China out of our lives, I got an eye-popping view of how far China had pushed in.

I began to connect the China I read about in the business pages with the one I found on the ground. When I read that Chinese textiles were flooding the country, I rushed to the mall to inspect the racks to see if this was reality or a national paranoia. When Wal-Mart downplayed its reliance on Chinese merchandise in a magazine, I headed for the neighborhood Super Wal-Mart to investigate for myself, hoping to catch the retailer in a lie. China’s place in the world suddenly seemed real, and personal.

My new connection to China explains another unforeseen benefit of our year without China. I was transformed as a consumer. I became mindful of the choices I was making. Shopping became something it never had been in decades of drifting through malls: meaningful. It was a satisfying transformation. By the end of the year, I wondered about two new questions: Could we live forever without China? And did we want to?

The events in this book are real. The characters are the members of my family. Our story is a slice of life in a vast and slippery global economy of infinite complexity. My hope is that readers will use my family’s experience to better understand how China is quietly changing their own lives and how the choices we all make as consumers shape China’s place in the world, and our own. I had always seen myself as a mere speck in the global economy. I still do. But the boycott made me see what I had missed before. I might be a mere speck in the larger world, but I can still make choices, and China is both limiting and expanding my options. I hope our story prompts readers to look closely at the choices they have available to them.

I recall a moment of doubt in the boycott’s early days. Maybe the words Made in China weren’t everywhere in our house, as it had seemed on a dark afternoon after Christmas in 2004. Maybe I had imagined the whole thing. Maybe we weren’t in for an adventure after all, because, really, how much could China have to do with our quiet American life on the other side of the world?

The answer came fast and early: plenty.

CHAPTERONE

Farewell, My Concubine

We kick China out of the house on a dark Monday, two days after Christmas, while the children are asleep upstairs. I don’t mean the country, of course, but pieces of plastic, cotton, and metal stamped with the words Made in China. We keep the bits of China that we already have but we stop bringing in any more.

The eviction is no fault of China’s. It has coated our lives with a cheerful veneer of cheap toys, gadgets, and shoes. Sometimes I worry about lost American jobs or nasty reports of human rights abuses, but price has trumped virtue at our house. We couldn’t resist what China was selling. But on this dark afternoon, a creeping unease washes over me as I sit on the sofa and survey the gloomy wreckage of the holiday. It seems impossible to have missed it before, yet it isn’t until now that I notice an irrefutable fact. China is taking over the place.

China emits a blue glow from the DVD player and glitters in the lights and glass balls on the drooping spruce in the corner of the living room. China itches at my feet with a pair of striped socks. It lies in a clumsy pile of Chinese shoes by the door, watches the world through the embroidered eyes of a redheaded doll, and entertains the dog with a Chinese chew toy. China casts a yellow circle of light from the lamp on the piano.

I slip off the sofa to begin a quick inventory, sorting our Christmas gifts into two stacks: China and non-China. The count comes to China 25, the world 14. It occurs to me that the children’s television specials need to update their geography. Santa’s elves don’t labor in snow-covered workshops at the top of the world but in torrid sweatshops more than 7,000 miles from our Gulf Coast home. Christmas, the day so many children dream of all year, is a Chinese holiday, provided you overlook an hour for church or to watch the Pope perform Mass on television. Somewhere along the way, things have gotten out of hand.

Suddenly I want China out.

It’s too late to banish China altogether. Getting rid of what we’ve already hauled up the front steps would leave the place as bare as the branches of the dying lemon tree in our front yard. Not only that, my husband Kevin would kill me. He’s a tolerant man, but he has his limits. And yet we are not cogs in a Chinese wheel, at least not yet. We can stop bringing China through the front door. We can hold up our hands and say no, thank you, we have had enough.

Kevin looks worried.

“I don’t think that’s possible,” he says, his eyes scanning the living room. “Not now, not with kids.”

He is nursing a cup of Chinese tea at the other end of the sofa. He hasn’t quite recovered from assembling our son’s new Chinese train, an epic process that lasted into the wee hours of Christmas morning. He looks a little pale and the two days of stubble on his cheeks aren’t helping. I have interrupted the silence to pitch my idea to him: for one year, starting on January first, we boycott Chinese products.

“No Chinese toys, no Chinese electronics, no Chinese clothes, no Chinese books, no Chinese television,” I say. “Nothing Chinese for one year, to see if it can be done. It could be our New Year’s resolution.”

He has been watching me with a noncommittal gaze. Now he takes a sip of tea, turns his head, and redirects his eyes to the bare wall on the opposite side of the living room. I had hoped for a quick sell, but I can see that this will take some doing.

“It will be like a scavenger hunt,” I suggest. “In reverse.”

Kevin is typically game to jam his thumb in the eye of conventional wisdom. The closest he came to a religious figure in his childhood was W.C. Fields. He would skip school to watch Fields in afternoon movies on the local channel out of Los Angeles. At 16, he took a year’s leave from high school and moved to Alaska for a job in a traveling carnival where he worked the dime toss and learned to speak carnie from the ex-cons who ran the rides. He returned to California, enrolled in community college, and spent eight years there, studying philosophy, gymnastics, and woodworking.

Kevin came by his rebel streak honestly. His father was a bitter teachers union organizer and political agitator who spent his weekends hiking nude in the Anza Borrego desert. I figure if I can tap into that rebel blood now, I can get Kevin on board for a China boycott.

“It can’t be that big a deal,” I tell him. “We don’t have a microwave. Our television has a thirteen-inch screen. With rabbit ears on top. Our friends think we’re nuts to live like we do, but I can’t see that we’re missing much. How hard can it be to give up China, too?”

Kevin keeps his eyes on the wall. I push on.

“We’re always complaining that the States don’t make anything any more,” I say, with a sweep of my arm. “We’ve said it a million times. You’ve said it a million times. Wouldn’t you like to find out for yourself if that’s really true?”

I see right away that the question is a mistake. Kevin lifts his brow and purses his lips in the exaggerated expression of a sad clown. I hear a soft rasp of air as he opens his mouth to speak, still not looking at me. I jump back in, quickly.

“We might save money,” I say.“Maybe we can finally stick to a budget, like we’ve been talking about for fifteen years. And it will be fun, sort of an adventure.”

I study Kevin’s profile. He has a square jaw and a nose that belongs on a movie star. But there is something wrong with his eyes. They have a glassy, faraway look and they are stuck on the scuffed green paint of the opposite wall. They can’t seem to turn my way.

I point out that my part-time job as a business writer means that I can do the heavy lifting when it comes to scouring the mall for merchandise from not-China. If there is anyone left in this busy world with time to waste, I say, it’s me.

“Not only that, I love reading those little labels that tell you where something is made,” I say. “You can leave that to me.”

Kevin may be too healthy to obsess over such details, but we both know that I am not. I have checked the labels on almost everything we own over the past couple of years. I take a perverse glee in tracking the downfall of the American empire by way of those little tags, which so infrequently bear the words Made in USA. It is the reason I know that we own a French frying pan, Brazilian bandages, and a Czech toilet seat. Those names were rare in our house. The one I spotted most frequently, maybe eight or nine times out of ten, was China. We would pause over the latest Chinese discovery, and then Kevin would say the words we both had on our minds: “Hell in a handbasket,” he would mutter with a shake of his head.

I wish now that I had not been so eager to share my Chinese findings with him. I need to get him to look past the obvious, that a China boycott is likely to turn our lives upside down. I need Kevin to set aside common sense, and personal experience, and plunge into uncharted territory with me.

“I’m not suggesting that we buy only American goods, just not things from China. And the kids, at one and four, are too little to know what they are missing. Can you imagine the howls if they were teenagers? If there is ever going to be a good time in this family for a China boycott, the time is now. And let’s be honest. If the checkbook sometimes dips into the single digits late in the month, it is due to a lack of money management skills, not a shortage of cash. Not everybody can afford a China boycott, but on your teaching salary and my writer’s pay, we can.”

At least I hope we can, I think.

“In any case, we can go back to our old ways next January,” I say. “China will be waiting for us. China will always be there to take us back.”

I check Kevin’s profile. He has decided to wait me out. It is his standard strategy, with good reason; it works nearly every time. When we disagree, he clams up, stands back, and lets me trip over my own feet. I remember seeing this same hazy look in his eyes, years ago, when I brought home a stray dog one afternoon and asked if we could keep it. Kevin paused at the front gate and said nothing. The beast sealed its fate when it erupted in snarls and charged Kevin, refusing to let him on the property. Kevin never uttered a word.

I see now that it’s time to pull out a big gun. I try to sound nonchalant.

“Some people said giving up Wal-Mart would be tough,” I say. “I can’t say we’ve missed a thing.”

At first, boycotting Wal-Mart seemed silly to me. I couldn’t see the difference between Wal-Mart and places like Kmart and Target when it came to issues like wiping out mom-and-pop stores and worker pay. True, I’d had a few unsavory personal experiences at the ancient Wal-Mart near our home. I had seen a man scream at an exhausted baby and on more than one occasion watched dying cockroaches pedal spiky legs into the air as I stood in the neon glare of the checkout line waiting to pay for underwear and diapers.

Then there were the standard reasons for picking on Wal-Mart—its bullying of suppliers and the blight on the landscape left by its abandoned stores, among other things. What got me on board for a Wal-Mart boycott was when I read that it barred labor inspectors from the foreign factories that churn out the $8 polo shirts and $11 dresses that hang on its racks. Even then, I could think of two nice things to say about Wal-Mart: It lets people sleep in their recreational vehicles in its parking lots, and it saves consumers collectively billions of dollars on everything from Tide to pickles.

It occurs to me that the Wal-Mart embargo is a good trial run for a China ban, since much of what it sells comes from China. I know this, because I read the labels on a lot of boxes at Wal-Mart in our pre-Wal-Mart-boycott days. Still, there is a key difference between a ban on Wal-Mart and one on Chinese goods. Ultimately, boycotting Wal-Mart requires just one thing: keeping your hands on the steering wheel and accelerating past the entrance to its vast parking lot. China, by comparison, blankets the shelves of retailers across the land, and not just the big-box stores but also perfumed boutiques and softly lit department stores and the pages of the catalogs that shimmy their way into millions of American mailboxes each day. China will not be so easily avoided.

I keep this last bit to myself. Besides, I can see that my Wal-Mart ploy has hit a nerve. The lines around Kevin’s mouth soften. His brow falls. He still has his eyes on the wall, but he is listening. A hostage negotiator would tell me I am making progress because I have him engaged. Keep him talking, the negotiator would tell me. Kevin had been slumped at the other end of the sofa but now he sits up and looks around the room. I try not to overplay my hand. I wait for him to make the next move. He turns his head and locks eyes with me.

“What about the coffeemaker?” he asks.

He is thinking about the broken machine that still sits on the kitchen counter despite brewing its last cup a month earlier. We picked it up at Target a couple of years ago. It was a memorable episode because it was the first time we noted China’s grip on the market for an ordinary household item. We stood in the aisle for 20 minutes, turning over boxes and looking at labels. Every box came from China. We shrugged and picked out a sleek black machine with an eight-cup pot. It sputtered to a halt one morning in November, but we left it sitting there, hoping it would somehow come back to life.

For weeks we have been boiling water and pouring it through a plastic filter on top of our coffee mugs. I don’t mind; it reminds me of camping trips to the mountains when we made coffee over the fire. But Kevin feels otherwise, and on cold mornings, when our kitchen takes on a cave-like chill and we are desperate for something hot, I can see his point. In asking about the coffeemaker, he wants to know if China is still fair territory in the search for a replacement.

“It’s December twenty-seventh,” I say. “You’ve got four days.”

Then I know I have him on board. He turns his head and looks over the chaos of the living room floor. He is making a mental list of other things he wants to add to our crowded household while he still has time. I say the place is half full but I can tell he would argue for half empty. I keep my mouth closed. This is no time to argue. In his mind he’s already making his shopping list and heading for the door, not once looking back. I picture a swirl of Chinese toys, socks, and shoes trailing after him before the door clicks to a close. Good riddance, I think, but my next thought surprises me. For a brief moment, I worry what we are in for.

Later, as I pick scraps of paper and torn boxes from the floor, I realize there will be additional complications, by which I mean my mother, a Greek chorus of one.

At 71, her sense of injustice is undiminished as that of a freshman philosophy major, which is what she was in 1951. Her preferred topics for discussion are the Old Testament, the birds in her backyard, proper English grammar, and the suffering of the poor, in no particular order. Her favorite rule is the golden one, and when she hears about our plans for a China boycott, she will suspect me of breaking it. She will think I am picking on an underdog breaking into the big leagues after ages in the muck. She will see a delicious opening for an argument.

“How would you like it if someone boycotted you?” she will begin.

Then she will pause to wonder if, perhaps, I am my mother’s daughter after all.

“Is it for human rights?” she will ask next. “Is it for the Chinese workers, suffering like slaves in those awful factories?”

My mother loves all mankind, and one of the ways she loves it is by arguing with it. In her world, there are no unworthy opponents. She has never uttered the words, Who cares what they think? She cares what everybody thinks, especially when they think the wrong things, in which case she views it as her duty to help them see the error of their ways. Once, during a trip to the Santa Monica Pier when I was eight or nine, I watched in terror as she argued with a huge, shirtless biker over whether the starfish he had gripped in his fist had the same number of points as the Star of David.

“The Star of David!” he exclaimed to nobody in particular, thrusting the dead creature toward the sky and careening across the planks of the pier.

My mother walked up to him.

“The Star of David has six points,” she said.

“Five points!” he roared.

“Six,” she said.

“Five!” he shot back.

A crowd began to gather. Silently, I wished for two things. First, that the biker would not kill my mother. Second, that the great planks of wood beneath my feet would shatter into splinters and I would careen downward into the sucking waves of the Pacific, 20 feet below, never to be seen again. The day was half lucky. The biker staggered off down the pier without violence to my mother but I remained firmly planted on the wood.

“No, it’s not for Chinese workers,” I will answer when my mother takes her first jab at me over the China boycott.

“Is it for the American workers, then? For the ones who have lost jobs to China?”

“No, it’s not for them either.”

“Is it for Tibet?”

“It’s not for Tibet, either, Mother,” I will say, “although it could be. Maybe it should be. Probably it should be, but it’s not politics.”

“Then what is it?” she will ask.

“It’s an experiment,” I will tell her. “To see if it can be done.”

“And can it be done?”

“I have no idea, Mother. That’s what we intend to find out.”

She will be disappointed. The wind will slip from her sails. She won’t be able to sink her teeth into this one. The word experiment will throw her off the scent. I come from a family of scientists and teachers—deeply religious scientists and teachers. Among the members of my clan, objecting to an experiment, to the pursuit of fact and knowledge, is as unlikely as objecting to someone taking piano lessons. It can’t be done. There’s no ledge on which to gain purchase and launch a protest. I will shut down my mother before she can get started.

I ball up the wrapping paper in my hand and toss it into a plastic bag I retrieve from the floor, then throw myself onto the sofa to savor my imagined victory over my mother. I feel a little guilty, because it is not nice to squish your mother, even in the abstract, or to deny her a juicy exchange about the miseries of the world, especially when she lives two time zones to the west and you only talk to her once a week. I decide to postpone telling her about the boycott as long as I can.

One of the children calls out for me from above. Naptime is over. I sigh a sigh of the sleep deprived, push myself to my feet and head for the stairs, and put away my mother, and China, for a while.

The children’s school is closed for the week so we spend the next four days chasing them around the house. It’s chilly outside so I let them go wild inside, turning a blind eye to Sofie jumping on the bed and Wes racing from room to room on a red scooter with a Dutch bell on the handle. Brrring, it clangs, as he loops the kitchen table and heads for the dining room. I make empty threats when he veers too close to his sister’s bare toes and real ones when he rolls directly over mine. I casually observe to myself that I am fast becoming one of those parents I swore I would never be, overly indulgent and ready to wheel and deal with the children over candy and television if it will buy me five minutes peace.

Wes swerves by again.

“Watch it!” I shout.

He grins and speeds away.

When he’s not on his scooter, Wes is on his new Chinese walkietalkie. He distributes handsets to everybody, including his baby sister, so he can keep a close eye on our movements around the house.

“What are you doing, Mama?” His voice comes over the handset high and scratchy, like he’s talking into a microphone under water. I pick up my handset and press a button with a wet thumb.

“The dishes,” I say and release the button.

“Oh,” comes his fuzzy response. Then, about five seconds later, “What are you doing now?”

“The dishes,” I say.

A little later, he buzzes me again.

“What are you doing, Mama?”

“Feeding the dog.”

“What are you going to do next?”

“Some more dishes.”

“Over,” he says.

We barely leave the house except to go shopping, an activity that seems decadent so soon after the orgy of Christmas morning toys and clothes. Our trips to the store are worrisome occasions. On the one hand, I worry that we will be locked out of the market for certain items for the next 12 months, a situation that would put the boycott in peril if Kevin, who I quickly assign the role of Weakest Link, gets fed up with the idea and tosses in the towel.

On the other hand, I worry that stockpiling supplies ahead of the launch date is a cynical attempt to circumvent the boycott by making it too easy to comply with its limits. At the same time, I figure I should delay saying no to Kevin, and anybody else in the family, during our final days of unfettered China bingeing. In any event, we don’t bring home anything glamorous or, to my surprise, anything Chinese. I pick up a couple of plastic storage bins made in Oklahoma and a package of marked-down Christmas cards, also made in the USA and, I notice, cheaper than the box of Chinese cards sitting next to it on the shelf. Kevin buys two pairs of Mexican jeans.

The coffeemaker turns out to be a nonissue, and a nonpurchase.

“I thought you wanted it,” Kevin says when I ask him about it one afternoon.

“Me? I don’t care about a coffeemaker,” I say. “You were the one who brought it up.”

“That’s because I thought you wanted it,” he says. “I only brought it up for your sake.”

“I don’t want it,” I say. “I’m fine with boiling.”

“Well, I don’t want it,” he says.

“Fine,” I say.

“Fine,” he says.

He will tell you I am the stubborn one, but I know better.

“Do you think we’ll make it?” I ask Kevin during a commercial.

“Until midnight?” he asks. “I doubt it.”

It’s New Year’s Eve, the last day of our lives as China junkies. We made lame excuses to our friends about Sofie coming down with a cold so we could do what we really wanted to do, which is stay home to stare at the television and watch the crystal ball drop over Times Square. I am giddy tonight, practically jumping out of my skin with anticipation over tomorrow morning. I can hardly wait to get this show on the road. It’s not every day you decide to do battle with the world’s next superpower, and the wide shots of teeming crowds of happy strangers buoys my resolve. Bring it on, I think.

Evidently, Kevin is not as hopped-up as I am.

“I’m not talking about tonight. I mean this year, without China,” I say. “Do you think we’ll make it through the year?”

Kevin shrugs and turns back to the tube.

The Weakest Link, I tell myself. Just wait and see.

I shouldn’t be so hard on him. I have a lousy record when it comes to sticking to New Year’s resolutions. I stayed true to one just once, the year I vowed to take the stairs every morning to the fourth-floor office where I worked at the time. It wasn’t much of a resolution since I was in the habit of taking the stairs instead of the elevator anyhow. There was nothing to it. It was like resolving to drink coffee or take a bath every morning. The other years, when I set my sights on training for a marathon or even making the bed every day, my resolve crumbled by mid-January, at best.

There is something else eating at me as I wait for midnight Eastern time. It takes me a few minutes to realize what it is, and when I do, it catches me off guard. It is regret. I can’t describe China as a friend. A billion people, a massive military buildup, a repressive government with unclear intentions. Inscrutable, they would have said in the old days, and they would not be far off the mark today. But China is something else as well: a relative.

Three centuries ago, my Chinese ancestor sailed to Germany, where he disembarked with his wife and young son. The trip over did not agree with Mrs. Chang. She promptly died. Mr. Chang fared better. He took a job as a caretaker to a German family, seduced the teenage daughter, and gave her a baby but no wedding ring. I imagine a whisper campaign over race mixing and illegitimacy but family lore is mute on the issue, along with the larger fate of Mr. Chang, his son, and his mistress. The child, a girl, survived. Her descendant, my great-grandmother, landed on Ellis Island in the 1870s and headed west for Nebraska.

My mother points to Mr. Chang to explain my younger brother’s treks through Asia and the languid fold of her grandmother’s eyelids. Years ago, my mother sailed the Yangtze, ate in decrepit restaurants, and never once fell ill. She gorges herself on Peking duck every chance she gets. Red is her favorite color.

“It is nature, not nurture, at work,” she insists.

As a child, black hairs occasionally sprouted on my pale head. I spied them in the mirror from several feet away, thick black lines against straw-colored wisps. The first time I spotted one I wondered if it had fallen out of someone else’s head and somehow reattached itself to mine. I plucked it out and laid it across my palm. It was shiny and inky black, perfectly straight, and twice as thick as my other strands, which were wavy and nearly white. In an instant I knew what it was: China reclaiming me three centuries and an ocean away from the motherland. No one could have told me otherwise.

Sometimes I scanned my head for more black hairs, but they were very few and by my teenage years they vanished for good. I would stand in the orange light of the bathroom and study the mirror for more signs of Asia, a curve of the lip or the eye, but there was nothing there. The face that looked back at me was as blandly suburban as Bermuda grass. It was disappointing. I wanted more China, not less.

It’s nothing personal, I remind myself now. And it’s only for a year.

The first day of January begins for me like every New Year’s Day of the past decade. I stay in my pajamas all morning and lie on the sofa to watch the Rose Parade on television, waiting for glimpses of the snow-capped San Bernardinos in the distance. Kevin and the children make a racket over pancakes in the kitchen. I love parades, but they make me weepy, and no parade makes me as weepy as this one. My nose stings and my eyes water at the sight of Palominos, rolling banks of flowers, and chubby Midwestern band kids getting red in the face as they plow down Colorado Boulevard.

As is my custom, I tune in to NBC so I can listen to commentary by Al Roker, whom I am half in love with. My eyes are wet and my nose is red, but Al’s dry wit keeps me from falling apart altogether. Without him, there’s a good chance I would descend into open weeping that might frighten the children. This morning, Al and the horses and the band kids have a special meaning for me. I tell myself that, no matter what lies ahead of us this year, there is no shortage of fine things forever out of China’s reach and within mine—the Rose Parade, Pasadena, and Al Roker serving as three quick examples. My nose stings again at the thought.

The parade is winding down when the telephone rings and Kevin calls me into the kitchen. It’s my best friend, an American expatriate married to a Frenchman, calling from Paris to wish us a happy new year. We talk almost every week and I am eager to share the latest news—to boast, really—about the China boycott. We exchange preliminaries, and then I tell her what we are up against with the dawn of the New Year.

Her response isn’t what I was expecting. It begins with a snort.

“You’ll be naked and broke,” she scoffs. “You’re a dreamer if you think you can fill your daily needs with things made in America. That’s a thing of the past. The whole basis of the American economy is people buying a bunch of stuff, and China makes it easier for them to do it by making it cheaper. People eat up everything China makes.”

I jump in to correct her.

“I didn’t say we were going to buy only American products, just not Chinese ones,” I say.

She doesn’t seem to notice.

“Every summer, when I go home to San Diego, I load up on clothes and toys for the kids, and do you know what I pay for all of it?” she says. “Next to nothing. Almost zero. It’s too cheap. There’s something wrong it’s so cheap. And almost everything is from China. But one of these days, China is going to get sick of selling stuff for nothing and then the States are going to get screwed because they’ve sent all their factories over there.”

She seems to be arguing in favor of a China boycott, which is why I can’t figure out why she is arguing with me. And she is not done yet.

“China’s not doing you any favors,” she says. “You just watch.”

I am flat-footed when someone comes right at me, angling for a fight. Even the most benign line of questioning can mix me up. A couple of years ago, another friend suggested that we all quit our jobs, pool our money, and buy a plot of land in Vermont to start a communal farm, complete with committees to oversee vegetable cultivation, sanitation, and barn mucking. I didn’t know what to say. When he brought it up a second time I panicked. I worried we might end up living in a compound in the snow, trapped in endless meetings over tractors and goats. I asked Kevin for advice on how to throw water on the idea.

“You could tell him we don’t want to,” he suggested.

I don’t know how Kevin comes up with this stuff.

I am nearly as clumsy this morning as I come to the boycott’s defense.

“I think it’s possible,” I tell my friend. “Not easy, but possible.”

She gets in a final dig.

“You’ll never make it,” she says.

We leave the matter there. We spend the next few minutes talking about her children, then my children, then her weather, then mine. We wish each other a happy new year once more, and then hang up.

The conversation is unnerving. I had expected unconditional support, which, after all, is what I have given her during our three decades of friendship. Maybe I should not be surprised. She has been the alpha female in our relationship ever since she moved down the street during the fourth grade and quickly established herself as the smartest girl in the class and the one with the best hair. My role always has been that of malleable and amusing sidekick, but I feel there are times, like now, when she ought to get with the program and refrain from throwing around her many and varied opinions.