29,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

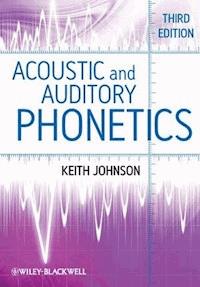

Fully revised and expanded, the third edition of Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics maintains a balance of accessibility and scholarly rigor to provide students with a complete introduction to the physics of speech.

- Newly updated to reflect the latest advances in the field

- Features a balanced and student-friendly approach to speech, with engaging side-bars on related topics

- Includes suggested readings and exercises designed to review and expand upon the material in each chapter, complete with selected answers

- Presents a new chapter on speech perception that addresses theoretical issues as well as practical concerns

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 361

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I Fundamentals

Chapter 1 Basic Acoustics and Acoustic Filters

1.1 The Sensation of Sound

1.2 The Propagation of Sound

1.3 Types of Sounds

1.4 Acoustic Filters

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 2 The Acoustic Theory of Speech Production: Deriving Schwa

2.1 Voicing

2.2 Voicing Quanta

2.3 Vocal Tract Filtering

2.4 Pendulums, Standing Waves, and Vowel Formants

2.5 Discovering Nodes and Antinodes in an Acoustic Tube

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 3 Digital Signal Processing

3.1 Continuous versus Discrete Signals

3.2 Analog-to-Digital Conversion

3.3 Signal Analysis Methods

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 4 Basic Audition

4.1 Anatomy of the Peripheral Auditory System

4.2 The Auditory Sensation of Loudness

4.3 Frequency Response of the Auditory System

4.4 Saturation and Masking

4.5 Auditory Representations

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 5 Speech Perception

5.1 Auditory Ability Shapes Speech Perception

5.2 Phonetic Knowledge Shapes Speech Perception

5.3 Linguistic Knowledge Shapes Speech Perception

5.4 Perceptual Similarity

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Part II Speech Analysis

Chapter 6 Vowels

6.1 Tube Models of Vowel Production

6.2 Perturbation Theory

6.3 “Preferred” Vowels – Quantal Theory and Adaptive Dispersion

6.4 Vowel Formants and the Acoustic Vowel Space

6.5 Auditory and Acoustic Representations of Vowels

6.6 Cross-linguistic Vowel Perception

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 7 Fricatives

7.1 Turbulence

7.2 Place of Articulation in Fricatives

7.3 Quantal Theory and Fricatives

7.4 Fricative Auditory Spectra

7.5 Dimensions of Fricative Perception

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 8 Stops and Affricates

8.1 Source Functions For Stops and Affricates

8.2 Vocal Tract Filter Functions in Stops

8.3 Affricates

8.4 Auditory Properties of Stops

8.5 Stop Perception in Different Vowel Contexts

Recommended Reading

Exercises

Chapter 9 Nasals and Laterals

9.1 Bandwidth

9.2 Nasal Stops

9.3 Laterals

9.4 Nasalization

9.5 Nasal Consonant Perception

Recommended Reading

Exercises

References

Answers to Selected Short-answer Questions

Index

This third edition first published 2012

© 2012 Keith Johnson

Edition history: Basil Blackwell Inc (1e, 1997); Blackwell Publishers Ltd (2e, 2003)

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Keith Johnson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, Keith, 1958–

Acoustic and auditory phonetics / Keith Johnson. – 3rd ed.

p. cm.

Previously pub.: 2nd ed., 2003.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9466-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Phonetics, Acoustic.

2. Hearing. I. Title.

P221.5.J64 2012

414–dc22

2011009292

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is published in the following electronic formats: ePDFs [ISBN 9781444343076]; ePub [ISBN 9781444343083]; Mobi [ISBN 9781444343090]

1 2012

Acknowledgments

I started work on this book in 1993 at the Linguistics Institute in Columbus, Ohio, and am grateful to the Linguistic Society of America and particularly the directors of the 1993 Institute (Brian Joseph, Mike Geis, and Lyle Campbell) for giving me the opportunity to teach that summer. I also appreciate the feedback given to me by students in that course and in subsequent phonetics courses that I taught at Ohio State University.

Peter Ladefoged had much to do with the fact that this book was published (for one thing he introduced me to Philip Carpenter of Blackwell Publishing). I also cherish our conversations about the philosophy of textbook writing and about the relative merits of Anglo-Saxon and Romance words. John Ohala commented extensively on an early draft with characteristic wit and insight, and Janet Pierrehumbert sent me ten long e-mail messages detailing her suggestions for revisions and describing her students’ reactions to the manuscript. I appreciate their generosity, and absolve them of responsibility for any remaining errors.

I was very fortunate to work in an incredibly supportive and inspiring environment at Ohio State University. Mary Beckman provided me with encouragement and extensive and very valuable notes on each of the book’s chapters. Additionally, Ilse Lehiste, Tsan Huang, Janice Fon, and Matt Makashay gave me comments on the speech perception chapter (I am grateful to Megan Sumner for suggestions and encouragement for the revisions of the speech perception chapter in this edition), and Beth Hume discussed the perception data in chapters 6–9 with me. Osamu Fujimura discussed the acoustic analysis in chapter 9 with me (he doesn’t completely agree with the presentation there).

My brother, Kent Johnson, produced the best figures in the book (figures 4.1, 4.5a, and 6.7).

For additional comments and suggestions I thank Suzanne Boyce, Ken deJong, Simon Donnelly, Edward Flemming, Sue Guion, Rob Hagiwara, SunAh Jun, Joyce McDonough, Terrence Nearey, Hansang Park, Bob Port (who shared his DSP notes with me), Dan Silverman, and Richard Wright. Thanks also to those who took the time to complete an “adopter survey” for Blackwell. These anonymous comments were very helpful. Many thanks to Tami Kaplan and Sarah Coleman of Blackwell, who helped me complete the second edition, and Julia Kirk, Anna Oxbury, and Danielle Descoteaux, who helped me complete the third edition.

This book is dedicated to my teachers: Mary Beckman, Rob Fox, Peter Ladefoged, Ilse Lehiste, and David Pisoni.

K. J.

Introduction

This is a short, nontechnical introduction (suitable as a supplement to a general phonetics or speech science text) to four important topics in acoustic phonetics: (1) acoustic properties of major classes of speech sounds, (2) the acoustic theory of speech production, (3) the auditory representation of speech, and (4) speech perception. I wrote the book for students in introductory courses in linguistic phonetics, speech and hearing science, and in those branches of electrical engineering and cognitive psychology that deal with speech.

The first five chapters introduce basic acoustics, the acoustic theory of speech production, digital signal processing, audition, and speech perception. The remaining four chapters survey major classes of speech sounds, reviewing their acoustic attributes, as predicted by the acoustic theory of speech production, their auditory characteristics, and their perceptual attributes. Each chapter ends with a listing of recommended readings, and several homework exercises. The exercises highlight the terms introduced in bold in the chapter (and listed in the “sufficient jargon” section), and encourage the reader to apply the concepts introduced in the chapter. Some of the questions serve mainly as review; but many extend to problems or topics not directly addressed in the text. The answers to some of the short-answer questions can be found at the end of the book.

I have also included some covert messages in the text. (1) Sample speech sounds are drawn from a variety of languages and speakers, because the acoustic output of the vocal tract depends only on its size and shape and the aerodynamic noiseproducing mechanisms employed. These aspects of speech are determined by anatomy and physiology, so are beyond the reach of cultural or personal habit. (2) This is a book about acoustic and auditory phonetics, because standard acoustic analysis tells only partial linguistic truths. The auditory system warps the speech signal in some very interesting ways, and if we want to understand the linguistic significance (or lack of it) of speech acoustics, we must pay attention to the auditory system. The linguistic significance of acoustic phonetics is also influenced by cognitive perceptual processing, so each of the chapters in the second half of the book highlights an aspect of speech perception. (3) There are formulas in the book. In fact, some of the exercises at the ends of the chapters require the use of a calculator. This may be a cop-out on my part – the language of mathematics is frequently a lot more elegant than any prose I could think up. In my defense I would say that I use only two basic formulas (for the resonances of tubes that are either closed at both ends or closed at only one end); besides, the really interesting part of acoustic phonetics starts when you get out a calculator. The math in this book (what little there is) is easy. (4) IPA (International Phonetic Association) symbols are used throughout. I have assumed that the reader has at least a passing familiarity with the standard set of symbols used in phonetic transcription.

Improvements Made in the Third Edition

Thanks to the many readers, teachers and students, who have provided feedback about how to improve this book. The main changes that teachers will notice are: (1) I reordered the chapters – putting the presentation of the acoustic theory of speech production earlier in the book and also touching on audition and speech perception early. I realize that there is a good argument for putting the audition and speech perception chapters toward the end of the book, and that the order of presentation that I have chosen presents certain complications for the teacher. I hope that the pay-off – being able to collect acoustic, auditory, and perception data on speech sounds together in each of the chapters 6–9 – is adequate compensation for this. (2) The digital signal processing chapter has been updated to be more compatible with currently available hardware and software, and the linear predictive coding analysis section has been reworked. (3) There is a new speech perception chapter that addresses theoretical issues, as well as the practical concerns that dominated the chapter in the second edition. I adopt a particular stance in this chapter, with which some teachers may disagree. But I also tried to open the door for teachers to engage with the book (and with students) in a theoretical debate on this topic. (4) Sections of the chapters introducing the acoustic theory of speech production, and vowel acoustics, have been rewritten to provide a clearer (and more correct) presentation of resonance and standing waves in the vocal tract. (5) The chapter on audition includes a new section on saturation and masking. (6) Many of the spectrograms in the book have been replaced with ones that are easier to interpret than those found in the previous editions. (7) Each chapter now ends with a selection of recommended readings.

Students won’t notice any changes between the third edition and the second – unless you are particularly nerdy and look up old editions of textbooks, or unless you are particularly unlucky and had to retake the course after the publication of this edition. As always, my wish for students who use this book is that learning about acoustic phonetics will be more fun and fascinating with the book than it would have been without it.

Part I

Fundamentals

Chapter 1

Basic Acoustics and Acoustic Filters

1.1 The Sensation of Sound

Several types of events in the world produce the sensation of sound. Examples include doors slamming, plucking a violin string, wind whistling around a corner, and human speech. All these examples, and any others we could think of, involve movement of some sort. And these movements cause pressure fluctuations in the surrounding air (or some other acoustic medium). When pressure fluctuations reach the eardrum, they cause it to move, and the auditory system translates these movements into neural impulses which we experience as sound. Thus, sound is produced when pressure fluctuations impinge upon the eardrum. An acoustic waveform is a record of sound-producing pressure fluctuations over time. (Ladefoged, 1996, Fry, 1979, and Stevens, 1999, provide more detailed discussions of the topics covered in this chapter.)

1.2 The Propagation of Sound

Pressure fluctuations impinging on the eardrum produce the sensation of sound, but sound can travel across relatively long distances. This is because a sound produced at one place sets up a sound wave that travels through the acoustic medium. A sound wave is a traveling pressure fluctuation that propagates through any medium that is elastic enough to allow molecules to crowd together and move apart. The wave in a lake after you throw in a stone is an example. The impact of the stone is transmitted over a relatively large distance. The water particles don’t travel; the pressure fluctuation does.

A line of people waiting to get into a movie is a useful analogy for a sound wave. When the person at the front of the line moves, a “vacuum” is created between the first person and the next person in the line (the gap between them is increased), so the second person steps forward. Now there is a vacuum between person two and person three, so person three steps forward. Eventually, the last person in the line gets to move; the last person is affected by a movement that occurred at the front of the line, because the pressure fluctuation (the gap in the line) traveled, even though each person in the line moved very little. The analogy is flawed, because in most lines you get to move to the front eventually. For this to be a proper analogy for sound propagation, we would have to imagine that the first person is shoved back into the second person and that this crowding or increase of pressure (like the vacuum) is transmitted down the line.

Figure 1.2 shows a pressure waveform at the location indicated by the asterisk in figure 1.1. The horizontal axis shows the passage of time, the vertical axis the degree of crowdedness (which in a sound wave corresponds to air pressure). At time 3 there is a sudden drop in crowdedness because person two stepped up and left a gap in the line. At time 4 normal crowdedness is restored when person 3 steps up to fill the gap left by person 2. At time 10 there is a sudden increase in crowdedness as person 2 steps back and bumps into person 3. The graph in figure 1.2 is a way of representing the traveling rarefaction and compression waves shown in figure 1.1. Given a uniform acoustic medium, we could reconstruct figure 1.1 from figure 1.2 (though note the discussion in the next paragraph on sound energy dissipation). Graphs like the one shown in figure 1.2 are more typical in acoustic phonetics, because this is the type of view of a sound wave that is produced by a microphone – it shows amplitude fluctuations as they travel past a particular point in space.

Figure 1.1 Wave motion in a line of seven people waiting to get into a show. Time is shown across the top of the graph running from earlier (time 1) to later (time 15) in arbitrary units.

Figure 1.2 A pressure waveform of the wave motion shown in figure 1.1. Time is again shown on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows the distance between people.

Sound waves lose energy as they travel through air (or any other acoustic medium), because it takes energy to move the molecules. Perhaps you have noticed a similar phenomenon when you stand in a long line. If the first person steps forward, and then back, only a few people at the front of the line may be affected, because people further down the line have inertia; they will tolerate some change in pressure (distance between people) before they actually move in response to the change. Thus the disturbance at the front of the line may not have any effect on the people at the end of a long line. Also, people tend to fidget, so the difference between movement propagated down the line and inherent fidgeting (the signal-to-noise ratio) may be difficult to detect if the movement is small. The rate of sound dissipation in air is different from the dissipation of a movement in a line, because sound radiates in three dimensions from the sound source (in a sphere). This means that the number of air molecules being moved by the sound wave greatly increases as the wave radiates from the sound source. Thus the amount of energy available to move each molecule on the surface of the sphere decreases as the wave expands out from the sound source; consequently the amount of particle movement decreases as a function of the distance from the sound source (by a power of 3). That is why singers in heavy metal bands put the microphone right up to their lips. They would be drowned out by the general din otherwise. It is also why you should position the microphone close to the speaker’s mouth when you record a sample of speech (although it is important to keep the microphone to the side of the speaker’s lips, to avoid the blowing noises in [p]’s, etc.).

1.3 Types of Sounds

There are two types of sounds: periodic and aperiodic. Periodic sounds have a pattern that repeats at regular intervals. They come in two types: simple and complex.

1.3.1 Simple periodic waves

Simple periodic waves are also called sine waves: they result from simple harmonic motion, such as the swing of a pendulum. The only time we humans get close to producing simple periodic waves in speech is when we’re very young. Children’s vocal cord vibration comes close to being sinusoidal, and usually women’s vocal cord vibration is more sinusoidal than men’s. Despite the fact that simple periodic waves rarely occur in speech, they are important, because more complex sounds can be described as combinations of sine waves. In order to define a sine wave, one needs to know just three properties. These are illustrated in figures 1.3–1.4.

Figure 1.3 A 100 Hz sine wave with the duration of one cycle (the period) and the peak amplitude labeled.

Figure 1.4 Two sine waves with identical frequency and amplitude, but 90° out of phase.

The second property of a simple periodic wave is its amplitude: the peak deviation of a pressure fluctuation from normal, atmospheric pressure. In a sound pressure waveform the amplitude of the wave is represented on the vertical axis.

The third property of sine waves is their phase: the timing of the waveform relative to some reference point. You can draw a sine wave by taking amplitude values from a set of right triangles that fit inside a circle (see exercise 4 at the end of this chapter). One time around the circle equals one sine wave on the paper. Thus we can identify locations in a sine wave by degrees of rotation around a circle. This is illustrated in figure 1.4. Both sine waves shown in this figure start at 0° in the sinusoidal cycle. In both, the peak amplitude occurs at 90°, the downward-going (negative-going) zero-crossing at 180°, the negative peak at 270°, and the cycle ends at 360°. But these two sine waves with exactly the same amplitude and frequency may still differ in terms of their relative timing, or phase. In this case they are 90° out of phase.

1.3.2 Complex periodic waves

Complex periodic waves are like simple periodic waves in that they involve a repeating waveform pattern and thus have cycles. However, complex periodic waves are composed of at least two sine waves. Consider the wave shown in figure 1.5, for example. Like the simple sine waves shown in figures 1.3 and 1.4, this waveform completes one cycle in 0.01 seconds (i.e. 10 milliseconds). However, it has a additional component that completes ten cycles in this same amount of time. Notice the “ripples” in the waveform. You can count ten small positive peaks in one cycle of the waveform, one for each cycle of the additional frequency component in the complex wave. I produced this example by adding a 100 Hz sine wave and a (lower-amplitude) 1,000 Hz sine wave. So the 1,000 Hz wave combined with the 100 Hz wave produces a complex periodic wave. The rate at which the complex pattern repeats is called the fundamental frequency (abbreviated F0).

Figure 1.5 A complex periodic wave composed of a 100 Hz sine wave and a 1,000 Hz sine wave. One cycle of the fundamental frequency (F0) is labeled.

Figure 1.6 A complex periodic wave that approximates the “sawtooth” wave shape, and the four lowest sine waves of the set that were combined to produce the complex wave.

Figure 1.6 shows another complex wave (and four of the sine waves that were added together to produce it). This wave shape approximates a sawtooth pattern. Unlike in the previous example, it is not possible to identify the component sine waves by looking at the complex wave pattern. Notice how all four of the component sine waves have positive peaks early in the complex wave’s cycle and negative peaks toward the end of the cycle. These peaks add together to produce a sharp peak early in the cycle and a sharp valley at the end of the cycle, and tend to cancel each other over the rest of the cycle. We can’t see individual peaks corresponding to the cycles of the component waves. Nonetheless, the complex wave was produced by adding together simple components.

Now let’s look at how to represent the frequency components that make up a complex periodic wave. What we’re looking for is a way to show the component sine waves of the complex wave when they are not easily visible in the waveform itself. One way to do this is to list the frequencies and amplitudes of the component sine waves like this:

In this discussion I am skipping over a complicated matter. We can describe the amplitudes of sine waves on a number of different measurement scales, relating to the magnitude of the wave, its intensity, or its perceived loudness (see chapter 4 for more discussion of this). In this chapter, I am representing the magnitude of the sound wave in relative terms, so that I don’t have to introduce units of measure for amplitude (instead I have to add this long apology!). So, the 200 Hz component has and amplitude that is one half the magnitude of the 100 Hz component, and so on.

Figure 1.7 shows a graph of these values with frequency on the horizontal axis and amplitude on the vertical axis. The graphical display of component frequencies is the best method for showing the simple periodic components of a complex periodic wave, because complex waves are often composed of so many frequency components that a table is impractical. An amplitude versus frequency plot of the simple sine wave components of a complex wave is called a power spectrum.

Figure 1.7 The frequencies and amplitudes of the simple periodic components of the complex wave shown in figure 1.6 presented in graphic format.

Here’s why it is so important that complex periodic waves can be constructed by adding together sine waves. It is possible to produce an infinite variety of complex wave shapes by combining sine waves that have different frequencies, amplitudes, and phases. A related property of sound waves is that any complex acoustic wave can be analyzed in terms of the sine wave components that could have been used to produce that wave. That is, any complex waveform can be decomposed into a set of sine waves having particular frequencies, amplitudes, and phase relations. This property of sound waves is called Fourier’s theorem, after the seventeenth-century mathematician who discovered it.

In Fourier analysis we take a complex periodic wave having an arbitrary number of components and derive the frequencies, amplitudes, and phases of those components. The result of Fourier analysis is a power spectrum similar to the one shown in figure 1.7. (We ignore the phases of the component waves, because these have only a minor impact on the perception of sound.)

1.3.3 Aperiodic waves

Aperiodic sounds, unlike simple or complex periodic sounds, do not have a regularly repeating pattern; they have either a random waveform or a pattern that doesn’t repeat. Sound characterized by random pressure fluctuation is called white noise. It sounds something like radio static or wind blowing through trees. Even though white noise is not periodic, it is possible to perform a Fourier analysis on it; however, unlike Fourier analyses of periodic signals composed of only a few sine waves, the spectrum of white noise is not characterized by sharp peaks, but, rather, has equal amplitude for all possible frequency components (the spectrum is flat). Like sine waves, white noise is an abstraction, although many naturally occurring sounds are similar to white noise; for instance, the sound of the wind or fricative speech sounds like [s] or [f].

Figures 1.8 and 1.9 show the acoustic waveform and the power spectrum, respectively, of a sample of white noise. Note that the waveform shown in figure 1.8 is irregular, with no discernible repeating pattern. Note too that the spectrum shown in figure 1.9 is flat across the top. As we will see in chapter 3 (on digital signal processing), a Fourier analysis of a short chunk (called an “analysis window”) of a waveform leads to inaccuracies in the resultant spectrum. That’s why this spectrum has some peaks and valleys even though, according to theory, white noise should have a flat spectrum.

Figure 1.8 A 20 ms section of an acoustic waveform of white noise. The amplitude at any given point in time is random.

Figure 1.9 The power spectrum of the white noise shown in figure 1.8.

The other main type of aperiodic sounds are transients. These are various types of clanks and bursts which produce a sudden pressure fluctuation that is not sustained or repeated over time. Door slams, balloon pops, and electrical clicks are all transient sounds. Like aperiodic noise, transient sounds can be analyzed into their spectral components using Fourier analysis. Figure 1.10 shows an idealized transient signal. At only one point in time is there any energy in the signal; at all other times pressure is equal to zero. This type of idealized sound is called an impulse. Naturally occurring transients approximate the shape of an impulse, but usually with a bit more complicated fluctuation. Figure 1.11 shows the power spectrum of the impulse shown in figure 1.10. As with white noise, the spectrum is flat. This is more obvious in figure 1.11 than in figure 1.9 because the ‘‘impulseness” of the impulse waveform depends on only one point in time, while the “white noiseness” of the white noise waveform depends on every point in time. Thus, because the Fourier analysis is only approximately valid for a short sample of a waveform, the white noise spectrum is not as completely specified as is the impulse spectrum.

Figure 1.10 Acoustic waveform of a transient sound (an impulse).

Figure 1.11 Power spectrum of the transient signal shown in figure 1.10.

1.4 Acoustic Filters

We are all familiar with how filters work. For example, you use a paper filter to keep the coffee grounds out of your coffee, or a tea strainer to keep the tea leaves out of your tea. These everyday examples illustrate some important properties of acoustic filters. For instance, the practical difference between a coffee filter and a tea strainer is that the tea strainer will allow larger bits into the drink, while the coffee filter captures smaller particles. So the difference between these filters can be described in terms of the size of particles they let pass.

Rather than passing or blocking particles of different sizes like a coffee filter, an acoustic filter passes or blocks components of sound of different frequencies. For example, a low-pass filter blocks the high-frequency components of a wave, and lets through the low-frequency components. Earlier I illustrated the difference between simple and complex periodic waves by adding a 1,000 Hz sine wave to a 100 Hz sine wave to produce a complex wave. With a low-pass filter that, for instance, filtered out all frequency components above 300 Hz, we could remove the 1,000 Hz wave from the complex wave. Just as a coffee filter allows small particles to pass through and blocks large particles, so a low-pass acoustic filter allows low-frequency components through, but blocks high-frequency components.

You can visualize the action of a low-pass filter in a spectral display of the filter’s response function. For instance, figure 1.12 shows a low-pass filter that has a cutoff frequency of 300 Hz. The part of the spectrum shaded white is called the pass band, because sound energy in this frequency range is passed by the filter, while the part of the spectrum shaded gray is called the reject band, because sound energy in this region is blocked by the filter. Thus, in a complex wave with components at 100 and 1,000 Hz, the 100 Hz component is passed, and the 1,000 Hz component is blocked. Similarly, a high-pass filter blocks the low-frequency components of a wave, and passes the high-frequency components. A spectral display of the response function of a high-pass filter shows that low-frequency components are blocked by the filter, and high-frequency components are passed.

Figure 1.12 Illustration of the spectrum of a low-pass filter.

Figure 1.13 Illustration of a band-pass filter. Note that the filter has skirts on either side of the pass band.

Band-pass filters are important, because we can model some aspects of articulation and hearing in terms of the actions of these filters. Unlike low-pass or high-pass filters, which have a single cutoff frequency, band-pass filters have two cutoff frequencies, one for the low end of the pass band and one for the high end of the pass band (as figure 1.13 shows). A band-pass filter is like a combination of a low-pass filter and a high-pass filter, where the cutoff frequency of the low-pass filter is higher than the cutoff frequency of the high-pass filter.

When the high and low cutoff frequencies of a band-pass filter equal each other, the resulting filter can be characterized by its center frequency and the filter’s bandwidth (which is determined by the slopes of the filter). Bandwidth is the width (in Hz) of the filter’s peak such that one-half of the acoustic energy in the filter is within the stated width. That is, considering the total area under the curve of the filter shape, the bandwidth is the range, around the center frequency, that encloses half the total area. In practice, this half-power bandwidth is found by measuring the amplitude at the center frequency of the filter and then finding the width of the filter at an amplitude that is three decibels (dB) below the peak amplitude (a decibel is defined in chapter 4). This special type of band-pass filter, which is illustrated in figure 1.14, is important in acoustic phonetics, because it has been used to model the filtering action of the vocal tract and auditory system.

Figure 1.14 A band-pass filter described by the center frequency and bandwidth of the filter.

Recommended Reading

Fry, D. B. (1979) The Physics of Speech, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. An older but still useful introduction to the basics of acoustic phonetics.

Ladefoged, P. (1996) Elements of Acoustic Phonetics, 2nd edn., Chicago: University of Chicago Press. A very readable introduction to acoustic phonetics, especially on the relationship between acoustic waveforms and spectral displays.

Stevens, K. N. (1999) Acoustic Phonetics, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. An authoritative, engineering introduction to the acoustic theory of speech production.

Exercises

Sufficient jargon

Define the following terms: sound, acoustic medium, acoustic waveform, sound wave, rarefaction, compression, periodic sounds, simple periodic wave, sine wave, frequency, cycle, period, hertz, amplitude, phase, complex periodic wave, fundamental frequency, component waves, power spectrum, Fourier’s theorem, Fourier analysis, aperiodic sounds, white noise, transient, impulse, low-pass filter, pass band, reject band, high-pass filter, filter slope, band-pass filter, center frequency, bandwidth.

Short-answer questions

1 What’s wrong with the statement “You experience sound when air molecules move from a sound source to your eardrum”?

2 Express these times in seconds: 1,000 ms, 200 ms, 10 ms, 1,210 ms.

3 What is the frequency in Hz if the period of a sine wave is 0.01 sec, 10 ms, 0.33 sec, 33 ms?

4 Draw a sine wave. First, draw a time axis in equal steps of size 45, so that the first label is zero, the next one (to the right) is 45, the next is 90, and so on up to 720. These labels refer to the degrees of rotation around a circle, as shown in figure 1.15 (720° is twice around the circle). Now plot amplitude values in the sine wave as the height of the vertical bars in the figure relative to the line running through the center of the circle from 0° to 180°. So the amplitude value at 0° is 0; the amplitude at 45° is the vertical distance from the center line to the edge of the circle at 45°, and so on. If the line descends from the center line (as is the case for 225°), mark the amplitude as a negative value. Now connect the dots freehand, trying to make your sine wave look like the ones in this chapter.

Figure 1.15 Degrees of rotation around a circle.

5 Draw the waveform of the complex wave produced by adding sine waves of 300 Hz and 500 Hz (both with peak amplitude of 1).

6 Draw the spectrum of a complex periodic wave composed of 100 Hz and 700 Hz components (both with peak amplitude of 1).

7 Draw the spectrum of an acoustic filter that results from adding two bandpass filters. Filter 1 has a center frequency of 500 Hz and a bandwidth of 50 Hz, while filter 2 has a center frequency of 1,500 Hz and a bandwidth of 150 Hz.