28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Collecting Action Figures presents an alphabetical survey of each of the major toy manufacturers and the whole array of action figures they produced. Covering everything from old-school GI Joe and Action Man figures, including the fantastic toys of Louis Marx and Mego, right through to the game-changing Star Wars 3-inch action figures of the 1970s and 1980s, this is the must-have reference guide for enthusiasts and beginners alike. With over 200 colour photographs, it details the history of action figures arising from the launch of fashion dolls in the 1950s; it describes the industry and consumer reactions to the first action figures; it reviews the many different incarnations that came to market; it looks at film and television tie-ins and finally, provides an essential guide to where to find gems, what to pay and how to look after them.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

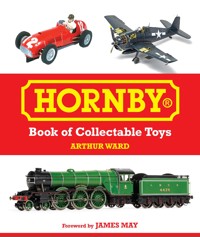

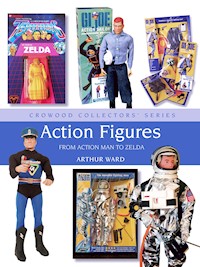

CROWOOD COLLECTORS’ SERIES

Action Figures

FROM ACTION MAN TO ZELDA

Large and small GI Joe – full-size Hasbro GI Joe and 1:35 scale Takara GI Joe’s GI Joe.

CROWOOD COLLECTORS’ SERIES

Action Figures

FROM ACTION MAN TO ZELDA

ARTHUR WARD

First published in 2020 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Arthur Ward 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 694 4

CONTENTS

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1PLASTIC TOYS COME OF AGE2AND ALONG CAME BARBIE3‘A DOLL FOR BOYS!’: GI JOE, THE US FIGHTING MAN4‘WE CHOOSE TO GO TO THE MOON’: ACTION FIGURES IN SPACE5THE RESPONSE TO THE REVOLUTION IN BOYS’ TOYS6ACTION MAN: GI JOE CROSSES THE POND AND PALITOY MAKES ITS MARK7GILBERT AND MEGO EMBRACE THE FILM AND TELEVISION MERCHANDIZING BONANZA8IN A GALAXY, FAR, FAR AWAY: STAR WARS’ FIGURES REIGN SUPREME9CONDITION, VALUES AND WHERE TO BUY10EPILOGUE: AND WHAT OF THE FUTURE?ACTION FIGURES TOP THE BEST-SELLER CHARTS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Kenner ‘Small Soldiers’ (1998) ‘Gorgonite Archer’ and ‘Chip Hazard’ of the Commando Élite.

DEDICATION

For my mother and father, who initiated my lifelong passion for action figures by buying my first GI Joe when we lived in Hong Kong, more than half a century ago.

And for my daughters, Eleanor and Alice, who have long been obliged to tolerate their father’s fascination for old toys.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Although responsibility for the words and photographs is entirely mine, I was lucky enough to benefit from the help and advice of several people who each significantly contributed to the value of this book. My sincere thanks, in alphabetical order, to Carol and Peter Allen, Lisa Bessinger, Bob Brechin, Ralph Ehrmann, Dave Grey, Mark Grundy, Keith Melville, Nick Millen and Jade Nodinot.

Other than the occasional copy of an advertisement or product leaflet, the great majority of the photography in this book is my own. However, four photographs are the copyright of Mark Grundy: the ‘Action Man Jeep and Trailer’, the ‘Action Man Tank Commander’, the ‘Action Man French Resistance Fighter’, and the ‘Action Man Green Beret’ outfit. Thanks Mark.

My good friend Dave Grey is responsible for the cool Photoshop work on the Action Man 7th Cavalry figure.

However, the frontispiece image I took featuring GI Joe holding a smaller figure is not the result of such Photoshop manipulation: the 12-inch figure is holding a 1:35-scale miniature action figure that was produced by Takara in 2004.

Trademarks and Brand Ownership

‘GI Joe’, ‘Action Man’, ‘Action Soldier’, ‘Action Marine’, ‘Action Pilot’, ‘Action Sailor’ and ‘America’s Moveable Fighting Man’ are all © & ™ Hasbro Inc.

Star Wars, The Force, The Dark Side & Star Wars action figures © & ™ Lucas Films Ltd, The Walt Disney Company, Hasbro Inc.

Airfix is a registered trademark © Hornby Hobbies Ltd.

Iron Man © &™ Marvel Entertainment, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company.

Superman, Batman, Batwoman, Batgirl, Catwoman © &™DC Comics, Inc. the publishing unit of DC Entertainment, a subsidiary of Warner Bros.

Barbie, Ken, Skipper, Hot Wheels, Fisher Price, American Girl, Mega Bloks and Jurassic World are all ©&™Mattel Inc.

Ballad of the Green Berets © Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler.

Mego is a trademark of Marty Abrams Presents Mego.

INTRODUCTION

Something very unusual happened to American youth during the 1964 Christmas vacation. As children explored the bounty of presents lying beneath festive trees, one gift elicited such a reaction of rapture from the boys amongst them that it flew in the face of established behaviour. Amongst anticipated gender-specific gifts such as Louis Marx’s ‘Rock ’Em, Sock ’Em’ robots, Aurora’s ‘Nuclear Airliner’ model kit or J.C. Higgins’ shiny and streamlined battery-powered ‘Rocket Jet’ bike headlight, the one they unwrapped most feverishly was… a doll.

Well, not a doll precisely. For although it was of similar height to Barbie, whose hour-glass physique had graced little girls’ bedrooms since 1959, and also came complete with a range of outfits and accessories to rival that fashionista’s wardrobe, GI Joe, for that is what this ‘doll’ was, differed from Barbie in a couple of very important ways. Firstly, he was what was called an ‘action figure’, never a doll. And secondly, guns rather than clutch bags were his accoutrements of choice.

Retailing at just $4 apiece, GI Joe was also a most affordable toy; in its inaugural year manufacturer Hasbro sold $23 million worth of figures and accessories, a remarkable sum for the time. When America’s ‘Movable Fighting Man’ crossed the pond in 1966 to be licence-built in Leicestershire by Hasbro licensee Palitoy, he was an equal success, and after a name change to Action Man, was voted Toy of the Year on his British debut. In fact, most enthusiasts agree that Palitoy were responsible for making much more of the toy line than Hasbro ever did during its eighteen-year tenure. For their part, Palitoy had settled on a product that sold far better than anything else they had ever manufactured, achieving the remarkable production statistic of an astounding thirty million of the 12-inch giants.

The summer following GI Joe’s introduction, Rosko Industries, one of Hasbro’s many competitors, succeeded in persuading Sears, then the retailer with the largest domestic revenue in the United States, to stock their ‘Johnny Hero’ figure, which marked the first of countless significant copies of GI Joe. However, even though, just like Hasbro’s toy, ‘Johnny Hero’ came dressed in combat gear and carried a rifle, because the term ‘action figure’ had not yet entered common parlance, Rosko’s product was classified as a ‘boy’s doll’, which naturally didn’t do the toy’s prospects any favours.

Action Man 7th cavalry figure.

Hornby Gladiators’ ‘Wolf’ action figure (1992).

The phenomenal success of GI Joe revealed that, just like their sisters, boys would happily play with miniature articulated figures, and got just as much pleasure from dressing them up in different ensembles before they imbued them with a life and, through them, let their imagination soar.

Just how this sea-change in the tastes of American boys occurred is the stuff of legend and the subject of this book: their new-found enthusiasm has spread rapidly around the globe and so completely that today, action figures are now amongst the most popular toys in the world.

Product Enterprises’ white ‘Talking Dalek’ (2001). On its launch, Stephen Walker, the company’s founder, said ‘The radio-controlled Dalek has been the star of the toy fairs this spring’.

CHAPTER ONE

PLASTIC TOYS COME OF AGE

Children have played with toys for millennia. Archaeological excavations of Bronze Age settlements in the Indus Valley have revealed toy whistles that are still capable of holding a tune, and have even exposed concatenated miniature animals featuring movable limbs and jaws – action figures, of sorts, from prehistory. Egyptian children amused themselves with wooden or pottery toy dolls complete with articulated limbs, and which even featured miniature wigs composed of braided hair. Roman youngsters were entertained by pushing along wheeled terracotta horses – they even had toy yo-yos.

When Greek children, especially girls, reached maturity, they were encouraged to put away such childish things, sacrificing them to the gods instead. In most cultures however, such extravagant destruction was avoided, for whether simple or complex, toys required a lot of effort to produce and as such were precious items to be cherished.

For centuries toys remained bespoke items, individual pieces fashioned by hand, often whittled from a piece of wood or assembled from scraps of woven fabric and stuffed with horsehair or goose down. To ensure their durability, toys took time to construct and were of such quality that they endured to be coveted by successive generations of children – treasured hand-me-downs made to last.

Toys for the Many

The industrial revolution changed all this. The rapid production of identical components and the resultant series assembly of commercial products enabled mass production, providing quality manufactured goods for the many and not just the privileged few. At last, an assortment of fabricated items – including toys – could be produced economically. For the first time, by the eighteenth century inexpensive toys were available for sale in shops, bedecking shelves alongside long-familiar utilitarian items.

And there was more: the revolution in paper manufacture, allied with the step-change developments that had revolutionized printing technology, now enabled the production of cheaper, less robust games and novelties such as pop-up books and toy theatres. Before long, what we now know as board games were also being enjoyed, and with the release of ‘Journey through Europe’ in 1759, John Jefferys produced the first. In 1761 came another major development, when cartographer John Spilsbury created the first jigsaw puzzle.

However, despite the appearance of such revolutionary egalitarianism, some toys remained out of reach of the masses until well into the nineteenth century. This was principally because a large proportion of them were still made from relatively expensive materials, such as heavy cast metal – and because lighter tinplate products generally featured hand-painted or litho-printed decoration, even these substantially flimsier objects remained costly. Thus for a long time, playthings were but a dream for the children of working-class families. Anyway, such progeny had no time for toys: they often spent their daylight hours toiling in factories and mills, and rarely had the opportunity to enjoy the luxury of playtime.

However, the advent of inexpensive lead diecasting at the turn of the twentieth century levelled the playing field as far as the production of cheap and easy novelties and knick-knacks was concerned. Although the hand-painted figures produced by William Britain weren’t cheap, many other toy soldiers could be purchased for pennies. Zinc alloys such as Mazak also meant that toy vehicles were now within reach of even the most restricted pocket. The ‘toffs’ could keep their delicate tinplate and parade-ground assemblies of artisan-finished soldiers, while ordinary children relished playing with diecast vehicles and roughly painted lead soldiers that stood up to any amount of rowdiness.

The new century even saw legislation restrict the use of child labour, which at last granted them some free time. Although it still promised oppressive prospects for those unfortunates aged thirteen or over, a 1901 Act forbade children under the age of twelve from working. Until then, incredibly, the law had permitted children aged nine or over to work up to sixty hours per week, night or day.

The Arrival of Plastic

However, it wasn’t until the arrival of plastic that the combination of truly inexpensive ‘pocket-money’ toys, and the freedom to enjoy them, transformed children’s playtime. Certainly without plastics, action figures, the subject of this book, would have remained out of reach to the many, just as in Victorian times dolls with porcelain bisque heads were only accessible to the privileged few. As far as action figures are concerned, plastic was the game-changer.

Plastic is a man-made material formed from mouldable polymers of a high molecular mass capable of deforming irreversibly without breaking; polymers also exist in nature in the form of shellac, amber, wool, silk and natural rubber. Polymers are even present in DNA and proteins. We are more familiar with plastic in its synthetic form, especially in its most common manifestations: polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride, the latter two materials being the basis of most of the figures in this book.

One of the British names most closely associated with plastic, Airfix started life in 1939, manufacturing inflatables, novelties and cheap plastic toys, such as these soldiers, which date from 1948.

For a short while, however, prior to the advent of polystyrene and PVC, another, now less well-known plastic, enjoyed its moment in the sun. Briefly cellulose, the main constituent of wood and paper, reigned supreme. An important structural component of the primary cell walls of green plants, cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on Earth. The cellulose content of cotton fibre, for example, is 90 per cent, while that of wood is 40–50 per cent. Today, cellulose is mainly used to produce paperboard and paper, but after its discovery in 1838 by the French chemist Anselme Payen, it served as the basis for the first successful thermoplastic polymer, celluloid.

Celluloid

Patented in 1869 by American John Wesley Hyatt, celluloid was initially used to make billiard balls and spectacle frames. A decade later, he was granted the patent for injection moulding the material, and the resulting possibilities were endless. In 1887 the Rev Hannibal Goodwin patented celluloid film, which became a staple of the photographic and movie industry for many years to come. By the turn of the century, celluloid was the main constituent in the manufacture of combs, causing a terminal decline in the popularity of tortoiseshell and horn, both previously the principal components in the manufacture of such items.

Prior to the introduction of celluloid, dolls were extremely fragile, with bodies of china or papier-mâché, heads of bisque, and limbs that were often formed from wax. They were collectable items more suitable for display, rather than for the antics of the nursery. England, Bavaria, France, Japan, Poland and the USA were the principal manufacturers of the new, cheaper, and more robust celluloid dolls. Despite the material being further improved in 1908, celluloid nitrate, to give the material its full name, was certainly not the answer to everything. Difficult to work, it was also unstable, and because it was an explosive polymer, it had the unfortunate habit of being readily flammable. Readers of a certain age might recall that even after 35mm acetate film replaced celluloid in the 1950s, for decades afterwards, the frame edges remained marked with the legend ‘safety film’.

Set of ‘Beatlemania’ figures by Spanish firm Emirober (1964).

Before he joined Airfix and ultimately Hasbro, owners of GI Joe, Peter Allen did a five-year engineering draughtsman’s apprenticeship at Lines Bros, owners of Tri-ang and the Arkitex plastic ‘Girder-and-panel’ construction set shown here, with which, for a short time, he found himself involved. Peter worked with the product’s designer, Geoff Bailey, whom he remembers as a ‘great guy, a fantastic boss who was always very encouraging’. Peter’s job utilized all his model-making skills as he prepared prototype models for the toy fair.

Despite its imperfections, the introduction of celluloid encouraged a frenzy of invention, and was the catalyst for a thermoplastics gold rush.

Bakelite

In 1899 Arthur Smith patented phenol-formaldehyde resins to replace ebonite for electrical insulation. Five years later, in 1904, Sir James Swinburne, the ‘Father of British Plastics’, formed The Fireproof Celluloid Syndicate and later, joined forces with Belgian Chemist Leo Baekeland to establish the Damard Lacquer Company, which in turn evolved into Bakelite, the famous brand name for the first truly successful thermoset phenol-formaldehyde material. Bakelite immediately assumed a position previously enjoyed by natural materials such as wood, ivory and ebonite, and very soon a wide range of everyday items were henceforth made synthetically. Unlike nitrate cellulose, Bakelite proved a truly stable and durable plastic, capable of being moulded into an infinite variety of household goods from radio cabinets to picture frames, bookshelves and lamp cases. Furthermore Bakelite was not a potential fire hazard. Because of its superb properties for electrical insulation, Bakelite is still in use today, especially in the automotive industry where it is employed under the hood of motor vehicles in a myriad hidden applications.

Dating from the late 1950s, this Airfix ‘Redskin’ bow-and-arrow set is typical of the versatility of the plastic medium.

Formica, another material that was initially developed as an electrical insulator, first appeared in 1910. This most utilitarian product was followed by an ultimately even more significant one, when in 1912, Russian Ivan Ostromislensky patented the polymerization of vinyl chloride, and PVC was born, a material that is also still very much part of our world today.

Polystyrene

Baekeland had patented the specific heat and pressure processes essential to forming his plastic material into its final form, but these patents expired in 1927. The year before, Germans Eckert and Ziegler had produced the first commercially successful injection-moulding machine, and this proved most suitable for moulding the rival plastics that now competed with Bakelite – especially polystyrene, a material synthesized by another German, Eduard Simon, back in 1839. The Germans were clearly the leaders in synthetics and chemical production, and in 1927 another Teuton, Otto Rohm, developed methyl methacrylate – the first clear plastic.

In 1937 Hans Kellerer, an Austrian this time, further perfected the injection-moulding process, introducing a fully automatic machine capable of continuous operation.

US toy firm Louis Marx’s answer to Hasbro’s ground-breaking GI Joe action figure was ‘Stony (Stonehouse) Smith’. As this photograph shows, Marx took full advantage of the potential of plastic moulding, arming their soldier to the teeth with copious accessories.

Another significant leap forwards occurred in 1930 when America’s DuPont corporation began researching the properties of nylon, and in 1935 they produced the first commercially viable synthetic fibre.

It wasn’t until BASF and Dow Chemical had completed their development work earlier in the 1930s that polystyrene, the other significant modern plastic, came to prominence. By 1937 the full-scale production of injection-moulded polystyrene had consigned cellulose to the trash can of history, well for everything other than, for a short period, photographic film. In company with this breakthrough, by 1939 chemists at ICI added the discovery of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) to the inventory of modern plastics. Their work resulted in a revolution in the manufacture of robust household products such as bowls and bottles, and, to society’s contemporary cost, the production of plastic bags.

In 1940, the USA was the first country to completely outlaw the use of volatile celluloid in toys. Having more serious matters to attend to perhaps, Britain and Germany didn’t follow suit until 1945. And anyway, during the war, Britain’s largest toymaker, Lines Bros (Tri-ang), were obliged to switch from the production of children’s scooters to the manufacture of Sten guns in support of the war effort.

Postwar Development of Synthetic Products

With the coming of peace, toymakers quickly embraced the range of new polymers now available. Previously these had been the sole province of the military industrial complexes of rival belligerents and used for the manufacture of the myriad switches, dials, stocks, pistol grips, oxygen masks and instrument binnacles employed in weapon systems.

By this time, however, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyethylene were available to use for more peaceful pursuits. Capable of being fashioned at high speed in the new moulding machines available for commercial exploitation, there appeared to be no limit to the available possibilities.

Japan’s wartime conquests in Asia and their consequent stranglehold on rubber production was another critical factor in the development of synthetic products, encouraging the allies’ urgent search for synthetic alternatives to latex. The war also obliged another of the original protagonists, Nazi Germany, to explore synthetics. The dramatic reversal of their fortunes soon after the invasion of Russia and the Caucasus saw the loss of the precious oil supplies previously taken for granted. Remarkably, before the Third Reich collapsed in 1945, Hitler’s Germany had become largely self-sufficient, its chemists notching up breakthrough after breakthrough.

Imperceptibly, by osmosis almost, the steady transition from very physical manual labour, often in an outdoor, agrarian setting, towards fixed hours in a factory or office, was all but complete by the dawn of the twentieth century. Peoples’ lives were transformed forever. One positive benefit of all this was that workers now enjoyed regulated leisure time. Successive laws also restricted the employment of child labour, and most youngsters now stayed at home after attending school or perhaps participated in less onerous work, such as part-time jobs like paper rounds or assisting the milkman with his deliveries.

Initially known as adolescents, by the 1950s a new social group, now called teenagers, had come to the fore. A by-product of American rock-and-roll, this new constituency was something new: a large, reasonably affluent group with time and spending money on their hands. Advertisers and brand owners loved them.

Increased prosperity also meant that even if such youngsters didn’t have jobs, many of them received regular pocket money or allowances, and it wasn’t long before the commercial world found ways of relieving them of this bounty. 45rpm records quickly became the almost exclusive province of older teenagers, but younger ones still played with, or collected toys, and at last all the technological and sociological advances converged to make them cheaply and readily available.

Immediately post-World War II, France’s Mokarex began giving away 54mm plastic figures with their coffee. As tastes changed, Mokarex concentrated on coffee machines, but in 1963 Atelier de Gravure, the manufacturers of these fine premiums, founded the famous Historex Napoleonic figures range.

International toy manufacturers took full advantage of the post-war development aid on offer to mitigate the damage caused by the worldwide conflict, especially the financial support granted by the United States’ Marshall Plan. Soon, grateful beneficiaries were investing in shiny new injection-moulding machines from manufacturers that included Arburg, Engel, Ferromatik and RH Windsor. Established companies such as America’s Louis Marx and Britain’s Lines Bros (parent of Tri-ang, Minic and Pedigree) were also quick to embrace such modern methods of toy production.

Ironically, those belligerents on the losing side often prospered most. With Germany at the heart of the Cold-War boundary between east and west, it was politically prudent for the Western democracies to bolster the fledgling Bundesrepublik, and consequently West Germany rose like a phoenix. In keeping with international practice, after World War II Japanese manufacturers also opted for injection moulding, and many of their plants switched from traditional tinplate to the manufacture of polystyrene and polyethylene products.

Japan’s initial resurgence wasn’t as rapid as that of democratic West Germany, however. Exchange rate fluctuations, especially the readjustment following the United States’ abandonment of the gold standard at the end of the 1960s, and its subsequent imposition of a 10 per cent surcharge on imported goods, made Japanese products increasingly expensive, and the nation’s competitive growth faltered. Nevertheless, at least one south-east Asian country more than filled the void left by Nippon’s absence, and by 1970 Hong Kong toy manufacturers were in the ascendant.

CHINA IN THE ASCENDANT

Action figures are an American creation, and GI Joe was the first. The British improved the concept, and most enthusiasts agree that Action Man is his smarter cousin, equipped with better uniforms and accessories and enjoying special features such as flocked hair and gripping hands, which meant that for the first time these fighting men could hold their guns properly!

Other European manufacturers such as Pedigree and Madelman further developed the genre. However, it was Hong Kong-based companies that elevated the design and consequently the appeal of action figures to even higher levels. Ironically, the originally GI Joe doll featured a scar that was cunningly intended to be a tell-tale, revealing if Chinese manufacturers had simply taken an impression from one of Hasbro’s toys and used it to cast a mould from which an infinite number of copies could be issued. By the late 1990s Chinese toy companies weren’t simply intending to follow – they led the way, the efforts of Hasbro, Palitoy and the like being left far behind, as historic anachronisms.

One of the first Hong Kong-based toy companies to enter the action-figure market wasn’t a newcomer at all, but one that had been around for quite a while. Blue Box Toys (BBI) was founded in 1952 by the late Peter Chan Pui, a man who spent sixty years working in the toy industry, and who in 2011 was presented with the Outstanding Achievement Award by the Hong Kong Toys Council. The first Blue Box toy, the famous ‘Drinks and Wets’ doll, was the first of a successful range of toys that saw the company establish factories in both Hong Kong and Singapore, and in the 1980s, on mainland China. With a broad range of infant and pre-school toys for girls and boys at its core, Blue Box has also developed electronic toys and other collectable items.

In 2000 Blue Box entered the action-figure market with a range of figures based on popular video games, such as Omega Boost and Fighting Force. In 2001 they produced ‘Élite Force’, a range of 12-inch military Special Forces figures, notable because of their revolutionary custom expression mechanism, by which facial expressions could be adjusted by turning a small screw in the back of the head, continuous product R&D being at the heart of Blue Box’s manufacturing ethos.

Blue Box Toys’ collectables arm, bbicollectable.com, home to the finest miniatures, markets Élite Force figures and vehicles in three scales: 1:6, 1:18 and 1:32. Boxed 1:6-scale figures, such as ‘Sgt Bones Wilson’, a US Air Force para-rescue soldier, and a strikingly garbed ‘US Navy Desert Ops Seal Team’ member equipped for HAHO (High Altitude High Opening) operations, are especially notable.

In 2014 Blue Box became partners with established American retailer Target to make a new, non-military series of 1:6 scale ‘Wild Adventure’ action figures available. Themed as both non-military and non-super heroic, and focusing instead on classic all-American sporting pursuits such as hunting and fishing, these new figures were only available online from Target’s website.

Established in 1987, Hong Kong-based Dragon Models Limited (Dragon, or DML) introduced its first 1:6 scale ‘New Generation’ action figure series in 1999, and since then has become one of the premier manufacturers of ‘traditional’ action figures in the world. (As such they are entitled to their own specific box, where much more information about this exciting company, a leader in action figures and, especially, in high-quality construction kits, can be found.)

In 1997 21st Century Toys began producing 1:6-scale accessory and uniform sets representing equipment used in the Vietnam War, and soon expanded their product line to include World War II, law enforcement, the emergency services, and modern armed forces’ accessories under the brand names ‘The Ultimate Soldier’ (TUS) and ‘America’s Finest’ respectively. The company offered more detail and historical accuracy than Hasbro had previously managed. 21st Century further expanded their line to include vehicles and a ‘Villains’ series. In 1999, the company further improved their designs with the introduction of the ‘Super Soldier’ body design, which featured no fewer than twenty-seven movable parts.

Blue Box (BBI) ‘Elite Force Pearl Harbor pilot’ box outer (2002).

For some reason World War II German designs have always proved the most popular with consumers – just ask plastic construction kit manufacturers such as Italeri and Tamiya – and it was the same for action figures. 21st Century Toys regularly received complaints about the preponderance of Nazi soldiers from the Third Reich in their range, whilst their competitors, such as Dragon, Blue Box, Sideshow Collectables and In The Past Toys, also seemed to focus exclusively on Third Reich subjects, and in 2002 they cancelled their 12-inch figure line. Since focusing on smaller scales, in 2014 21st Century Toys introduced a new action-figure brand, ‘Ultimate Soldier XD’, which, at 1:18 scale, was considerably smaller than traditional military action figures. However, the new scale at least had the advantage of being suitable for similarly scaled vehicles and large weapons systems to be more practically produced.

Sideshow Collectables started out in 1994. They originally created toy prototypes for major toy companies such as Mattel, Galoob and Wild Planet, but in 1999 began to market their own line of collectables, beginning with the ‘Universal Classic Monsters’ 8-inch action-figure licence, and then creating items in the more established 1:6-scale format that sold through speciality markets. At this time they also changed the suffix to their brand from ‘toys’ to ‘collectables’.

Sideshow has forged collaborative relationships with Hollywood filmmakers and special-effect houses including Guillermo del Toro, Legacy Effects, Spectral Motion, Amalgamated Dynamics Inc. and KNB EFX to produce some of the most sought-after collectables from blockbuster films such as Iron Man,The Transformers,The Avengers,Hellboy,Predators,Alien 3 and Alien vs Predators.

Sideshow Collectables is currently in partnership with Marvel, Disney, WB, Lucasfilm, DC, Blizzard Entertainment and others to create products from properties such as The Marvel Universe,The DC Universe,Star Wars,Alien and Predator,Terminator,The Lord of the Rings,G.I. Joe,Halo,World of Warcraft,Star Craft II,Mass Effect 3,Diablo 3, and many more.

Sideshow Collectables is also the exclusive distributor of Hot Toys’ (see below) collectable figures in the United States, North and South America, Europe, Australia and throughout most Asian countries. With its headquarters in Kowloon, Hong Kong’s Hot Toys Ltd was established in 2000 and began life concentrating solely on 1:6-scale military action figures. Since 2003, however, the company has branched out and secured licences and merchandizing rights for a wide range of major movie products. These include Avengers,Pirates of the Caribbean,Bat Man: The Dark Knight,The Terminator,Alien and Superman series, and a range of Hollywood legends including Marlon Brando, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Lee and James Dean. Musicians such as Michael Jackson and Wong Ka Kui, founding member of the Hong Kong rock band, Beyond, have also been immortalized in 1:6-scale plastic by Hot Toys.

Blue Box (BBI) ‘Elite Force Pearl Harbor pilot’ contents.

Going that extra mile to achieve scale realism, Hot Toys has secured patents for a couple of particularly clever innovations. One, the ‘Parallel Eyeball Rolling System’ (PERS), takes Palitoy’s ‘Eagle Eyes’ to a new level. The other, ‘The Interchangeable Faces Technique’ (IFT), a component of its DX series, actually enables customers to change their action figure’s expression: in seconds, a simple tool can alter Batman’s demeanour from a square-jawed, no-nonsense grimace, to his trademark sardonic smile.

Hot Toys has complemented its 1:6 figures with a range of large 1:4-scale figures and busts, a ‘Movie Masterpiece Series’ (MMS), a ‘Power Pose’ (PPS) series of predominantly ‘Iron Man’ characters as well as the sophisticated and consequently relatively expensive, 1:6-scale MMS diecast range

Established in 2003, the Hong Kong-based DID Corporation owns extensive manufacturing facilities in mainland China, where it produces its own figures (ODM: Own Development Manufacture), and products on behalf of other manufacturers such as Hasbro in the UK and Bandai in Japan (OEM: Original Equipment Manufacturer). DID is well known for producing excellent 12-inch military action figures from conflicts ranging from the Napoleonic Wars to World War II. Soldiers, samurai, fashion figures and movie characters all fall within DID’s remit, accompanied by an extensive range of 1:6-scale vehicles and accessories, which even include tiny 1:6-scale leather shoes!

Hong Kong’s Dominance in the Production of Plastic Toys

The Japanese invasion of China in 1937, and their capture of Shanghai, had encouraged a wave of migration to Hong Kong. The Chinese civil war that followed Japan’s surrender in 1945 further expedited the flow of refugees to the Crown Colony. Amongst those migrants were many industrialists bent on relocating there to take advantage of its relative freedoms and excellent logistics, such as Hong Kong’s deep harbour (most suitable for merchant ships) and its established international airport. The fact that the territory’s existing commercial and administrative infrastructure was based on tried and tested British legal practice was another perceived bonus.

Promptly, entrepreneurs such as Peter Chan Pui, founder of Blue Box Toys, toy and model railway manufacturer Kader’s Ting Hsiung-chao, and the entrepreneur Lam Leung-tim, known as ‘LT’, whose company Forward Winsome Industries expanded from the manufacture of a yellow plastic duck in 1948 – alleged to be Hong Kong’s first plastic toy – began to spearhead the colony’s dominance in the production of plastic toys. LT struck up an enduring friendship with Hasbro’s Alan Hassenfield, which saw the licensed production of GI Joe and, later, ‘Transformers’. By the late 1970s, Hong Kong had become synonymous with the production of plastic, especially toys such as action figures.

In 1971, Airfix used all sorts of plastic for both the figure and parachute canopy of their ‘Skydiver’, which, the box claimed, ‘Goes up like a kite – comes down like a parachute’. I wonder how many really soared to 150 feet.

With everything established to encourage the adoption of new materials and high-speed methods of production, toy manufacturers worldwide eagerly embraced the new possibilities. Even well-established toy companies adapted production to suit this new environment. One of them, the Ideal Novelty and Toy Co., which had been founded in 1907 and can credibly claim to be the inventor of the teddy bear (see box), was one of the first manufacturers to produce a truly modern plastic doll when they introduced the ‘Toni’ series in 1949.

Their new doll was retailed as a joint promotion with the Toni Permanent Company, then a leading exponent of the permanent wave hairstyle. Since 1934, Ideal had enjoyed enormous success with its series of ‘Shirley Temple’ dolls, each of which featured a mohair wig of tumbling curly locks. The ‘Toni’ doll was equally popular, and little girls were encouraged to endlessly wash, comb, perm and style the doll’s hair.

‘Toni’ came along at the right time and was able to take advantage of another new plastic, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), which had only recently been added to the growing lexicon of plastics. ABS proved the perfect material for action figures. It was easy to mould and proved extremely robust, capable of withstanding any amount of roughhousing from excitable youngsters. Combined with the softer and more flexible PVC, developed some forty years previously and perfect for items such as capes, boots and shoes, belts, rifle slings and suchlike, ABS plastic was durable enough to survive the regular handling that resulted from endless outfit changes, and robust enough to survive almost anything other than the most damaging encounters with unyielding obstacles.

Ideal followed their ‘Toni’ doll in 1956 with ‘Miss Revlon’, which, as its name suggests, was another figure analogous to the world of beauty and cosmetics. ‘Toni’ and ‘Miss Revlon’ were enormously successful, but were soon to pale in comparison with the new girl on the block – and even though Ideal rushed out the short-lived clone ‘Mitzi’, they were unable to compete with Barbie, who arrived in 1959 and instantly overwhelmed the competition.

British Manufacturers

In Britain, doll manufacturers Rosebud, D.G. Todd & Co (whose pre-war composition ‘Roddy Doll’ resurfaced in hard plastic in 1957) and Alfred Pallet’s Cascelloid Ltd (the forerunner of Palitoy) had long prevailed over others in the domestic toy doll market. Lines Bros was always hard on their heels, their Tri-ang brand possessing the largest toy factory in the world, a 750,000-square-feet establishment at Merton in Surrey. Tri-ang’s Pedigree brand had long counted on girls as customers, its hard plastic dolls being hugely popular in Britain. But other than its ‘Little Miss Vogue’ range, even by the late 1950s its products were largely traditional and followed established lines, pursuing the trends rather than setting them.

The trendsetter was right around the corner.

CHAPTER TWO

AND ALONG CAME BARBIE

Ruth Handler noticed that her daughter Barbara didn’t play with toy babies – she preferred her dolls to be dressed like adults, and when she played with them, her interaction mimicked the behaviour of grown-ups. Consequently, Ruth reckoned there might be a gap in the market – perhaps other young girls had a similar inclination. Fortunately, because her husband Elliot was a director of the Mattel toy company, she was in the unique position of being able to do something about it.

However, when Ruth first proposed her idea to Mattel’s management, Elliot and his colleagues didn’t share her enthusiasm, and it wasn’t until she discovered a German toy doll whilst on vacation in Europe that she resolved to pursue her idea further. With ‘Bild Lilli’ safe in her luggage, a doll with an adult figure that had been on sale since 1955 and matched her original concept, she went straight back to Mattel to show them what she envisaged. This time she was more successful.

Though not a comic-strip blonde bombshell like Lilli – a worldly-wise working girl who featured regularly in a popular comic strip in Die Bild-Zeitung, the popular daily tabloid – the doll that her husband’s company committed itself to producing was still endowed with assets that Marilyn Monroe would have been proud of. She was guaranteed to stand out in every way.

Using ‘Lilli’ as a template, the doll that Mattel design engineer Jack Ryan finally came up with shared many of the original’s features. Satisfied that they had found a winner, the prototype was given the green light, and Ruth named it Barbie, after her daughter Barbara.

The inspiration for Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler’s Barbie, ‘Bild Lilli’ was launched on 12 August 1955 and produced until 1964. Its design was based on the comic-strip character ‘Lilli’, created by Reinhard Beuthien for the German tabloid Bild. During a visit to Germany in 1956, Ruth Handler thought ‘Lilli’ was exactly the type of doll that young American girls would play with.

Before young girls played with fashion dolls such as Barbie, and ‘Lilli’ before her, they were expected to be satisfied with traditional dolls such as this ‘I am a Baby Rosebud Doll’ from the early nineteen-fifties.

As we have seen, by the mid-1950s developments in production, especially in the field of plastic injection moulding, meant that it was now easy to manufacture inexpensive but very robust dolls. But more importantly, instead of being offered only baby or infant dolls, little girls could now choose an up-to-the-minute teenage fashion doll that reflected the real world and met their aspirations – exceeded them in fact. Barbie was what little girls had always wanted – they just hadn’t realized it until Ruth Handler’s doll made it manifest.

Barbie made her debut at the American International Toy Fair in New York on 9 March 1959, and within a year nearly a third of a million were sold.

Louis Marx & Co subsequently acquired the rights to ‘Lilli’, and in March 1961 sued Mattel for copyright infringement. Mattel counter-sued, and the matter was settled out of court in 1963. In 1964 Mattel finally acquired the rights to the ‘Bild Lilli’ doll themselves, and saw to it that production of the Fräulein ceased.

While Mattel won’t release an exact figure regarding the number of ‘Barbies’ sold each year, in March 2009 they announced that three dolls were sold each second, and it is estimated that well over a billion Barbie dolls have been sold worldwide, in over 150 countries.

MATTEL

Mattel, Inc. was founded in California in 1945, and since then its brands such as Fisher-Price, Barbie, Hot Wheels, Matchbox and Masters of the Universe have deservedly secured a position in the Fortune 500 for the business. Deriving its name from a combination of the surnames of founders Harold ‘Matt’ Matson and Elliot Handler, the business perhaps owes its fame mostly to Elliot’s wife Ruth, creator of Barbie, the firm’s most successful toy line. However, before the curvaceous doll’s introduction in 1959, Mattel achieved its first success with 1947’s ‘Uke-A-Doodle’, a toy ukulele that also doubled up as a music box. ‘Turn Handle and it Plays Real Music – Two Toys in One!’ promised the box art. Mattel also enjoys the honour of being the first commercial sponsor of the Mickey Mouse Club TV series in 1955.

In 1960 Mattel introduced ‘Chatty Cathy’, a talking doll that revolutionized the toy industry, and was followed by a flood of other pull-string talking dolls and toys that came on the market throughout the 1960s.

Mattel went public in 1960 and was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1963. Another enormous success, Hot Wheels, first appeared in 1968. In 1971 Mattel even spent $40 million buying ‘The Ringling Bros’ and ‘Barnum & Bailey Circus’ for $40 million from owners the Feld family.

Accounting difficulties in 1974 saw the Handlers leave the company. However, by 1975, under the stewardship of former vice president Arthur S. Spear, Mattel was back on track, and by 1977 was consistently achieving profits. In 1979 Mattel spent $12 million adding ownership of the ‘Holiday on Ice’ and ‘Ice Follies’ franchises to its entertainment portfolio.

Based on the stories of the heroic warrior ‘He-Man’ who battles against the evil lord ‘Skeletor’ and his armies of darkness for control of ‘Castle Grayskull’, the ‘Masters of the Universe’ toy line was one of Mattel’s most successful action-figure ranges. At the time of writing, the author watched a mint-on-card (MOC) example of MOTU’s ‘Skeletor in Battle Armour’ receive more than forty bids on eBay before selling for £1,210. Not bad for a figure dating from 1983!