Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

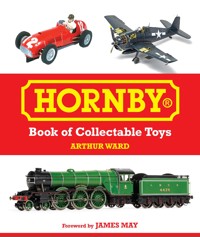

Hornby can trace its roots back to the very start of the 20th century and has since become one of the most iconic names in toy manufacturing, whose toys have delighted generations of children and collectors around the world. Its rich history is intertwined with that of many other famous toymakers, and today Hornby is the custodian of several heritage brands, including Airfix, Corgi and Scalextric. The Hornby Book of Collectable Toys vibrantly tells the story of their magical world of toys, from the early Meccano years through to the present day. Drawing on his experiences as an author, photographer, and interviewer of some of the greatest names in the British toy industry, Arthur Ward brings the industry to life. Packed with original colour photos, many previously unpublished, enthusiasts and novices will find something for them within these pages.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 289

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Foreword by James May

Introduction

Timeline

1 Baby Boomers

2 Collecting – An Irrational Passion

3 Toys Become a Thing

4 New Horizons

5 The Big Four – Airfix

6 The Big Four – Corgi

7 The Big Four – Hornby

8 The Big Four – Scalextric

9 Hornby Hobbies’ Subsidiaries

10 Other Famous British Toy Brands

11 Collecting, Condition, Values, Display and Storage

Appendix: The Top 40 Hornby Hobbies Collectable Toys

Bibliography

Index

FOREWORD

If I’d been born 30 years later than I was, I think I would have been addicted to computer games. The alignment of the stars, however, conspired to deliver me into the pre-digital world, and only just into the era of colour.

Yet I believe I had a flight simulator, a driving game, an early edition of SimCity, and a shoot-’em-up games console. They all took the form of physical toys that were at best electro-mechanical but for the most part utterly inanimate. The wheels went round on toy cars, but that was about it. The graphics card of the PC was in my head, fired by imagination, and it worked a treat. I was as much in the cockpit of the Airfix Mk IX Spitfire as the 2024 James May would be if playing War Thunder.

Toy history is a fascinating and underrated avenue of serious study. Historic toys tell us how we (or, more correctly, our parents) thought we would turn out; as the engineers, train drivers and pilots of the future. Toy manufacture embraced new technologies quickly. Airfix and their rival kit makers were early adopters of the new art of injection-moulded plastic. Hornby Railways and Scalextric did so much to spur the miniaturisation of electric motors and, ultimately, digital control systems. Where would the science of die-casting be without the insatiable appetite of children for toy cars? The principals of foolproofing assembly sequences, much vaunted in Japanese manufacturing, are evident in the engineering of Airfix kits. Toys are important.

The toys and models on these pages were educational, long before that cloying prefix was attached to anything. What I know today about aviation, cars and railways started with them. I am indebted to them, and would be a different person otherwise.

They were also magical. I’m not one of those people who bemoans the short attention spans and thirst for instant gratification amongst today’s young. I think we were just as guilty. I could complain that World of Tanks doesn’t require you to build your tanks first, but then, my neighbour Jim, almost 100 years old, thinks Airfix is ‘cheating’ because the parts are preformed. He comes from a time when making a model aeroplane meant starting with a piece of wood and a penknife.

But there is something about physical toys and models that trumps virtual ones. I was an Airfix obsessive (I still make the odd one) and had a whole air force and army. Corgi allowed a lad or girl to own a car collection that would rival Jay Leno’s, but it would fit in a box under your bed. A mildly enhanced Hornby train set was a way of taking control of a whole world, and anyone could be a world champion in Scalextric, driving a specially prepared car that would sit in the palm of your hand, and was beautiful.

They survive, these brands that were so formative in my life, and they are thriving. This is a book of their greatest hits and, like old pop songs, will trigger deep emotions, all of them happy.

Computers are for emails.

James May

INTRODUCTION

Without the efforts and achievements of one man, Liverpool’s Frank Hornby, this book would be quite different. It would certainly have a different title. Whilst he was not alone in harnessing the potential of new industrial techniques to produce toys, Frank Hornby – a businessman and inventor who explored numerous profitable avenues, many outside his immediate comfort zone – was a true pathfinder. He even became a conservative MP in 1931 at 68 years of age. Fittingly, for such a dynamo, his name lives on today and will forever be associated with model railways, Meccano construction sets and Dinky Toys. Outside his home, ‘The Hollies’ – appropriately enough located in Station Road, Maghull, a northern suburb of Liverpool – can be found a blue plaque dedicated to ‘Frank Hornby Toy Maker’.

Frank Hornby, 1863-1936. A colossus.

Like Airfix, Hornby is a name synonymous with toys and hobbies. Interestingly, Airfix is now part of Hornby Hobbies’ stable of iconic toy brands but, ironically, Hornby and its famous Meccano brand were once owned by Airfix, who bought Meccano-tri-ang in 1971 for £2,740,000, picking up the famous Dinky Toys brand at the same time. Keep up, as you will discover from reading this book, the British toy business is very incestuous.

Continuing with the interwoven theme, it is worth mentioning here that the sprawling factory complex in Margate – now the home of Hornby Hobbies and its sub-brands Corgi, Hornby Railways, Scalextric and Airfix – was once the headquarters of Rovex Ltd, and became the final location of Charles Wilmot and Joe Mansour’s International Model Aircraft Ltd, which produced FROG plastic construction kits, the only British competitor to give Airfix a run its money in the 1950s and 1960s.

When toy production resumed in Britain after World War II, Rovex, which was then a small company based in Richmond, Surrey, was doing sterling business selling relatively cheap plastic train sets to the retailer Marks & Spencer Ltd. They soon came to the attention of toy giant Lines Bros (Tri-ang), which purchased them in 1951, relaunching them as Tri-ang Railways. In 1954, Lines Bros installed the now Rovex Scale Models Limited in a brand-new factory in Margate, Kent, from where model trains and FROG plastic construction kits were manufactured.

Meccano Magazine, March 1924. The first issue of Meccano Magazine was published in 1916 as a four-page bi-monthly publication. The first copies were given away free, but in 1918 a fee of 2d was introduced.

The possibilities with Hornby’s Meccano construction toy were endless and an infinite variety of buildings and machines could be built. Spare parts were essential and small components could be neatly housed in this branded tin.

Tri-ang and the Big Toy Makers catalogue 1975.

Upon the death of Frank Hornby in 1936, his son Roland became Chairman of the company and George Jones became Managing Director. Jones was the instigator of Hornby Dublo, the smaller 1:76 scale alternative to the larger ‘O’ gauge, which was 1:48 scale – what the Americans call ‘Quarter Scale’. Hornby Dublo was introduced in 1938 and, though interrupted by World War II, became the predominant scale for model trains.

At the end of World War II, Hornby immediately resumed production of its famous Dinky Toys and Meccano construction sets. A shortage of specialist materials meant that the Hornby-Dublo range was somewhat delayed, a situation exacerbated by the return of material shortages caused by another war – this time in Korea. However, in 1954, the year Tri-ang Railways moved to Margate, back in Liverpool Hornby-Dublo received its first completely new post-war locomotive – the standard 2-6-4T locomotive – which was introduced alongside suburban coaches and an expanding wagon range.

In 1964 the monolithic Lines Bros purchased Meccano Ltd and finally acquired Hornby Trains, which they moved from Liverpool to Margate, merging it with their own Tri-ang and Hornby range to create Tri-ang Hornby Model Railways. For the first time, Hornby model trains had been separated from its Meccano and Dinky siblings and Frank Hornby’s legacy was dismembered. After a 45-year run, Hornby’s large ‘O’ gauge range was finally discontinued in 1965.

American inventor, athlete, magician and toy-maker Alfred Carlton Gilbert invented the Erector construction toy that was Meccano’s trans-Atlantic competition.

This fine Bugatti was constructed from Meccano as long ago as the 1950s, but is typical of what the toy was capable of building.

Every Boy’s Hobby Annual, 1937.

Pages from an IMA catalogue showing just some of the extensive range of flying model aircraft that the company produced.

Issue No 143 of The Modern Boy, November 1930. The Amalgamated Press published a total of 610 issues between 1928 and 1939.

TRI-ANG

In Victorian times, brothers George and Joseph Lines’ company G. & J. Lines made wooden toys. George soon lost interest in play things and went into farming, leaving Joseph – Joe – Lines to carry on with toys. Joe had four sons but only three of them, William, Walter, and Arthur Edwin Lines went into the toy business. Three lines make a triangle – hence the Tri-ang brand name. Lines Bros became a huge toy company, claiming to be the largest in the world. Certainly, the Lines Brothers’ factory in Merton, south London, was one of the biggest ever constructed. The resultant Tri-ang Railways quickly became the only competitor to Hornby and introduced a delightful range of plastic ‘HO-OO’ model railways that though not of the quality of its rival’s famous diecast metal Dublo range, presented a far cheaper and more accessible alternative.

UPHEAVAL IN THE 1970S

However, there was to be no let-up in the volatility of the British toy industry, for in 1971, at the peak of their power and with over forty companies worldwide, Lines Bros called in the official receiver and the group was broken up and sold off. Together with its Margate Factory, Rovex Tri-ang Ltd (with Hornby Railways among its portfolio) was sold to British conglomerate Dunbee-Combex-Marx, who had bought the former Marx UK subsidiary in 1967. In turn, Dunbee-Combex-Marx went into receivership in 1980 and Hornby became Hornby Hobbies and went public in 1986.

In 1971, Airfix Industries acquired Meccano and Dinky, taking over Frank Hornby’s legendary Binns Road factory in Liverpool to become one of the UK’s largest toy manufacturers.

The 1970s was a decade of industrial and economic malaise in Britain. Unemployment kept rising, there were frequent strikes and, at times, inflation exceeded 20 per cent. Britain’s exports were uncompetitive – not a good thing for businesses such as Airfix and Dunbee-Combex-Marx (DCM), which both depended on international sales. In 1981, Airfix called in the receivers, as DCM had done the previous year. Although its plastic construction kit business remained profitable, Airfix was burdened down by Meccano and Dinky, whose factory in Binns Road, Liverpool was a cauldron of industrial unrest. Many Airfix staff first heard that they had lost their jobs at the January toy fair that year.

During World War I the tank had been a revelation. Although the classic rhomboid form would soon change, this 1920s tin-plate toy epitomises the design of the earliest metal monsters.

Fortunately, by the end of 1981, Airfix had risen from the ashes, to be saved by US conglomerate General Mills. They tasked their UK subsidiary Palitoy, home to the famous Action Man, to steward them towards renewed success.

In 1986, another US giant, Borden Inc., purchased Airfix and in turn tasked their British subsidiary Humbrol to carry the torch. Humbrol – manufacturers of the iconic enamel paints sold in the tiny tinlets – had long been associated with Airfix, so it seemed a logical fit (and for a few years Allen & McGuire, a private equity firm based in Dublin, took over the management of Humbrol).

However, this was not to be a marriage made in heaven, because in 2006 Humbrol itself went into receivership and was sold to Hornby Hobbies.

And what became of Hornby itself, I hear you ask? Well, following the collapse of DCM in 1980, Hornby became Hornby Hobbies and in 1981 a management buyout saw the company back on a sound footing to the extent that it went public in 1986 and, as we know, is now the home of Airfix, which it purchased in November 2006.

In 2008 Hornby purchased Corgi for £8.3m from Hong-Kong based Corgi International Ltd. At the time of the announcement, then Hornby chief executive Frank Martin told The Guardian newspaper, ‘We intend to build on the brand’s super heritage and invest to build its premier position in the market.’

Enthusiasts will know that the famous Corgi brand originated as part of Mettoy in Northampton in the 1930s and was famously the first die-cast car range to feature windows and opening doors and bonnets. It was named after the queen’s favourite breed of dog – the Welsh Corgi – which is still a feature of the brand’s logo and a nod to its long-time manufacturing base in Swansea. When, following its acquisition by Mattel, the factory closed in 1991, it employed more than 1,000 people. For a time, Mattel also owned Dinky & Matchbox. As mentioned earlier, the British toy industry presented a convoluted story….

The machine gun changed warfare forever. This tin-plate JWB toy Maxim gun dates from the inter-war years.

‘The bomber will always get through’, prime minister Stanley Baldwin told parliament in 1932. Fear of ruin from the air was part of the Zeitgeist of the inter-war years. British firm Astra made a popular range of searchlights and anti-aircraft (AA) toys, which no doubt added to customers' anxiety.

There is lots more to the story to come, but as this is The Hornby Book of Collectable Toys, it is only fitting to mention, albeit briefly at this point, Scalextric, the fourth of the major names in Hornby Hobbies’ quartet of venerable brands.

Meccano Magazine, 1941. This august publication survived in more or less its original form from 1916 until 1972, after which it was published as a quarterly until 1981.

THE SLOT CAR REVOLUTION

Scalextric started life as ‘Scalex’ and was produced by London-based Minimodels Ltd, founded by former toolmaker Bertram ‘Fred’ Francis in 1947. Starting with clockwork tin-plate cars, Francis’ business grew to the extent that it was obliged to move to a new, larger factory in Havant, Hampshire in 1952. In the toy business, clockwork as motive power had begun to lose its appeal. Something new was needed.

Slot cars, of sorts, had appeared as early as 1912, being pioneered by US toy manufacturer Lionel – a kind of American Hornby and, like their British counterpart, most famous for model railways.

By the 1960s slot racing mechanisms had evolved from tracks that unsurprisingly owed more to model railways than grand prix circuits, to model raceways that carried low voltage electricity to drive the tiny motors built into each racer. Power was transferred from track to car via metal guide slots into which fitted a kind of swivelling blade located under the front of the car to conduct the electricity. Speed – governed by the amount of voltage applied – was varied by a resistor in a hand controller.

Employing accepted slot car practice, Francis adapted his tin-plate cars and unveiled Scalextric at the Harrogate Toy Fair in 1957. It was an immediate success and demand was enormous, far outstripping Minimodels’ capacity. This encouraged Francis to sell to Line Bros, which transferred production to Rovex in 1968. When in turn Line Bros was acquired by DCM, production of Scalextric was transferred to Margate alongside Tri-ang Hornby Railways. We know what happened to DCM, and so at the start of the 1980s Scalextric was operated under a management buyout by Wiltminster Ltd. In 1986 when Hornby Hobbies became a PLC, Scalextric returned to the fold and since then, innovations such as 360-degree spin-around chassis, flip-over mechanisms and the patented Magnatraction, which ensures racing cars stay on the track, have taken Scalextric to new heights.

TIMELINE

15 May 1863 Frank Hornby born in Liverpool, England.

1879 Frank leaves school to work as a cashier in his father’s provisions business.

1899 After his father’s death Frank Hornby became a bookkeeper for David Hugh Elliott who ran a meat importing business in Liverpool. In his spare time Hornby begins to make toys for his sons from pieces he cut from sheet metal. Discovered that different sized pieces with predrilled regularly spaced holes could be bolted together to make a variety of playthings. The world of construction toys was born.

January 1901 Hornby patented his invention as ‘Improvements in Toy or Educational Devices for Children and Young People.’ He borrowed £5 off his employer, David Elliott, to cover cost. Hornby & Elliott become partners and set up a small manufacturing concern adjacent to Elliott’s existing business.

1902 Rebranded ‘Mechanics Made Easy’ sets go on sale.

1903 1,500 sets sold.

1907 Hornby sets up a new plant to meet demand and registers the ‘Meccano’ trade mark.

1908 Elliott leaves the business.

1910 Meccano logo appears – annual turnover reaches £12,000.

1912 Meccano France established in Paris.

1920 The Hornby Clockwork Train (O gauge), enamelled tin-plate appears, becoming part of the Hornby Series and later Hornby Trains.

1931 Frank Hornby, by now a millionaire, is elected Conservative MP for the Everton constituency; he stands down at the 1935 General Election.

1934 Dinky Toys arrive in toy shops.

21 September 1936 Frank Hornby dies of a chronic heart condition complicated by diabetes.

1938 The Hornby Dublo model railway system is introduced.

1950 British toy giant Lines Bros (Tri-ang) acquire model train maker Rovex.

1954 Lines Bros relocate Tri-ang Railways and Rovex to a purpose-built factory in Margate, Kent.

1964 Lines Bros acquires Hornby and Meccano.

1971 Lines Bros is broken up. The model railways, then marketed as Tri-ang Hornby, were sold to the new Dunbee-Combex-Marx group, but the rights to the Tri-ang brand were sold elsewhere.

1 January 1972 Hornby Railways is established.

1980 Hornby Railways becomes independent again and shares its factory space with Scalextric.

2006 Hornby Hobbies acquires model paint manufacturer Humbrol and its subsidiary Airfix.

2008 Hornby Hobbies acquires diecast model car brand Corgi.

CHAPTER 1

BABY BOOMERS

I am a baby boomer, one of those born between 1946 and 1964. Like so many things, however, this generational classification has more to do with America than the

United Kingdom. The USA saw a steady and significant increase in its birth rate throughout this period, whereas with so many young men home from active service overseas, Britain experienced a massive spike immediately after the end of World War II in 1946 with things settling down thereafter.

I also consider myself a ‘boomer’ for another reason – I grew up with the bomb. Whilst my American friends learned to ‘Duck & Cover’, I was told how to ‘Protect & Survive the A-Bomb’.

Merit Popular Roulette. British manufacturer J. & L. Randall’s Merit brand was a market leader in the 1950s and 1960s and placed regular advertisements for its products in Meccano Magazine.

The end of World War II did not only see an increase in the birth rate – it also saw the start of the Cold War. The terrifying prospect of a nuclear World War III began with the signing of the Truman Doctrine in March 1947, which was designed to counter the expansion of the Soviet Bloc. The formation of NATO followed in 1949 and the nuclear standoff began. Terrifyingly, the only thing that appeared to prevent the world destroying itself in an act of global self-immolation was the appropriately named MAD – Mutually Assured Destruction – a policy adopted by East and West, which meant that if either side launched its nukes, everyone would die.

Despite living with this Sword of Damocles dangling above our heads, youngsters of my generation did not think much about nuclear war. Even though my late father was a soldier, and I spent a few years of my childhood living in West Germany – aware that, across the border, the East German enemy probably had an arsenal of nuclear weapons – I still was not that worried. Dad said the prevailing winds favoured the west if the Soviet Bloc unleashed its thermonuclear store cupboard.

A GOLDEN AGE FOR CHILDREN

My generation was more concerned with other pressing issues – like whether we had enough pocket money to buy an Airfix kit, or how to free the wheels of a Hornby locomotive that had become entwined with carpet fluff, or stressing about if we would ever be able to complete a full set of A & BC Chewing Gum Ltd’s Battle of Britain bubblegum cards. These were the things that really mattered to us.

Despite growing up in a world with no internet, no smartphones, no computers, no social media apps, a maximum of three television channels (only two until 1964) and hardly anything other than our tellies and transistor radios employing electronic components, we had a great time.

We made our own entertainment at home and during the hours of daylight, weather permitting, outdoors as often as not. In the days before health and safety was a thing, playing outdoors also often meant climbing trees to dangerous heights or breaking off their thinner branches, stripping them of twigs and foliage and making spears or javelins, which we would launch with abandon, often directly at each other.

Sometimes our benign deforestation would result in enough material with which to construct a den – a secret hideaway – in which we could gather with friends and enjoy a kind of independence from our parents.

Regardless of whether we were swinging precariously from tree limbs or crawling around inside our dank and dark temporary Damocles, we inevitably returned home with grazed knees, jeans ruined by stubborn grass stains, myriad cuts and bruises and worst of all, painful stinging nettle inflammation, which seemed to take forever to calm down.

First broadcast on BBC Television in 1957, Pinky & Perky were the two most popular porkers in Britain. Licensed toys abounded, such as these glove puppets modelled by Eleanor.

Caps were mainly used in toy pistols, but they could be especially irritating when thrown in plastic cap bombs.

Sometimes, we would return home with a champion conker, the substantial seed of the horse chestnut tree, still attached to its string after vanquishing lesser examples. When, in the early 1970s, violently swinging Clackers – a pair of hard acrylic spheres attached to threads in a similar manner to conkers – became a craze, we often returned home with badly bruised wrists. Little wonder they were soon deemed a ‘mechanical hazard’ and banned.

Hong Kong was the nexus of the international plastic toy business in the 1960s and 1970s.

During the dark nights of autumn and winter or when the weather was especially inclement, we played with our toys at home and during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, before the distraction of electronic games like Atari’s tennis-like Pong (honestly, two paddles and a ball on a monochrome screen was a revelation), or Taito’s 8-bit Gunfight, famous because it was the first video game to depict human-to-human combat, this meant unboxing old favourites like train sets, slot car tracks, die-cast cars and lorries or assembling an Airfix kit.

When we were not playing with our toys and games there was always television. Colour TV was first broadcast in Britain in 1967, but only in a limited way on the new channel BBC 2, and it would not be until 1969 that it was available on BBC 1 and ITV. In fact, until 1975 black and white televisions continued to outsell colour sets and, for most of our childhoods, we Baby Boomers had to make do with distinctly monochrome programmes.

This did not really matter of course, because Andy Pandy, The Flowerpot Men and The Woodentops still hit the spot.

Better known for its tin-plate toys, post-war Japan gave Hong Kong a run for its money as far as plastic toys, like this wristwatch, which was ‘Like Mother’s’, were concerned.

Despite ending World War II bankrupt and bereft of its once mighty empire, Britain enjoyed a place at the victors’ table, albeit a far less influential one than the USA or USSR. Consequently, it still bathed in the misguided idea that it had released the free world from the shackles of Nazi tyranny singlehandedly and had also been a crucial impediment to Japanese expansion in the Far East. Certainly, Britain’s victories during the Battle of Britain in 1940 and at El Alamein in North Africa in 1942 had been significant, as had been the critical role of the boffins at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire who broke the Nazi’s Enigma code, but apart from this and its role as a vital staging post for the invasion of Europe in 1944, the nation very much played second fiddle to Roosevelt and Stalin.

Nevertheless, Britain’s somewhat subordinate role during the conflict did not prevent it from making a series of movies that depicted British stoicism and derring-do. I spent some of my childhood in London’s Shepherd Bush in the 1960s and I well remember exploring undeveloped bomb sites even then, but this did not make me think that our country was in any way damaged. Far from it, we had won the war outright, a notion that movies like In Which We Serve, Sink the Bismark, The Dam Busters, Ice Cold in Alex and The Cruel Sea appeared to perpetuate. They were also black and white movies, which meant that even if we had had a colour television set, it would have made no difference. And anyway, long before my family possessed a colour television, I was able to enjoy colour movies, such as The Battle of Britain, Waterloo and Patton on the big screen at the then Hammersmith Odeon.

Baby Boomer boys also devoured World War II-based television programmes, most of them imported from America, such as Hogan’s Heroes, Garrison’s Gorillas, Dad’s Army, Man Hunt, A Family at War, Colditz, Danger UXB and Piece of Cake. Some of these programmes such as Hogan’s Heroes and Dad’s Army inspired diecast toys and Airfix even made a now very rare flying Colditz Glider.

Movies like 1969’s The Battle of Britain had an enormous impact on the British toy industry with brands such as Dinky Toys snapping up the licence to produce die-cast models of the true stars of the production: the aircraft of RAF Fighter Command and the German Luftwaffe.

Dinky Toys did not disappoint, going to a lot of trouble to produce excellent 1:72 scale examples of key warplanes from the conflict. There were two versions of the Luftwaffe’s Me 109 fighter – a now very sought-after yellow-nosed one in 1940 period green and blue camouflage and, for some reason, a version in desert camouflage – a lovely Supermarine Spitfire and an equally accurate Hawker Hurricane and last, but by no means least, a Ju 87 ‘Stuka’ dive bomber, which, at the press of a button, dropped its underslung cap-firing bomb. All these models also featured electric spin-a-prop motors that enabled the propeller to revolve at a furious rate.

In 1971 the giant Lines Bros concern (Tri-ang/ Rovex) had been acquired by new startup Dunbee-Combex-Marx. Part of the deal included FROG plastic construction kits. Soon after the acquisition of this brand, Airfix’s great domestic rival (until Matchbox joined the fray and began manufacturing plastic construction kits) released a series of 1:72-scale construction kits of adversarial pairs of aircraft licensed to United Artists’ blockbuster epics.

Model Car Manual by G.H. Deason, published in 1949.

To my knowledge, apart from Airfix’s Waterloo Wargame from 1975, its Fighter Command Game from 1976 and Airfix Dogfighter, a flight-combat video game for Microsoft Windows released in 2000, none of the significant brands covered in this book – Hornby, Corgi, Scalextic and, of course, Airfix – really got caught up in the war gaming Zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, which occupied so much leisure time. And, apart from Airfix Dogfighter, I am talking about traditional, analogue war gaming of the kind that H. G. Wells, author of the seminal 1913 book Little Wars (full title, Little Wars: a game for boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books) would be familiar. Wells, a pacifist, enjoyed playing with William Britain’s hollow-cast lead figures of which he had thousands, knocking them down with small sections of wooden dowel fired from spring-loaded cannon.

POST-WORLD WAR II EXPLOSION

The explosion in model making in Britain post-World War II not only saw an increase in the domestic manufacture of injection-moulded construction kits (the US already had a well-established industry led by firms like Revell and Aurora) of aircraft, ships, military vehicles, cars and model railway accessories, but alongside the developments in polystyrene production, there was also an extensive industry in the manufacture of highly detailed 54mm white-metal model soldiers, with manufacturers such as Hinchcliffe, Hinton Hunt, Almark, Mignot, Rose, Prince August, Sarum, Chota Sahib, New Hope Design, Barton Miniatures and Tradition of London. British modellers also embraced figure kits from overseas, such as those manufactured by Series 77 and Imrie Risley in the USA and Andrea Miniatures, Pegaso and Belgo from Europe. Back in the day, I eagerly purchased new figures from shops like Under Two Flags and Seagull Miniatures and, for inspiration, I followed the efforts of modellers such as Roy Dilley, Shepherd Paine and Ray Lamb.

Set of plastic Beatlemania figures from Spanish firm Emirober (1964).

Marx Daleks. Mint and boxed, ball bearing-equipped Rolykins are particularly sought after.

Nowadays it is unusual to find new white-metal figures; they have largely been replaced by resin, a material that was first adopted on a large-scale by Belgian model maker and manufacturer, Francois Verlinden, in the 1980s. Of course, there were always polystyrene figures to be had, 54mm Airfix Collectors Series mounted and foot figures and their same size but titled 1:32 scale groundbreaking Multipose figure range. Since the 1960s, fans of the Napoleonic era who preferred working with plastic could opt for figures manufactured by the French brand Historex, who made one of the most comprehensive ranges imaginable and eagerly sold spare parts too. However, in the days before online ordering, most of us purchased our Historex figures by mail, ordering from their long-term distributor, Historex Agents in Dover.

Dennis Fisher’s War of the Daleks board game from the 1970s.

Less well detailed, and primarily intended for wargaming, were the smaller metal figures that ranged in scale from tiny 1:300 scale used for armour, infantry and aircraft through to 15mm, 25mm and 28mm (the most popular wargaming scales and, of course 1:87 (HO scale), the gauge in which Airfix’s famous boxes of soft plastic figures proudly reside. I guess that wargames with huge play areas might still employ 54mm figures of the type made famous by William Britain (this is the same size as the popular 1:32 scale plastic figures of which Airfix is equally prolific). Apart from almost singlehandedly reviving the figure painting and wargaming industry in the face of the onslaught of computer games in the 1980s, Games Workshop’s fantasy Citadel Miniatures and Warhammer 40K tabletop miniatures continue to be enormously influential.

Fantasy and sci-fi related toys and figures are not a new thing. In the 1930s, American manufacturer Louis Marx produced lots of tin-plate toys, many of them related to popular radio programmes. One of their best, the Buck Rogers Rocket Space Patrol toy is now enshrined for permanent display in a gallery in the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum in Washington DC. Following the launch of Earth’s first manmade satellite, Sputnik, in October 1957, toy manufacturers rushed to cash in. One of them, Japan’s Yonezawa, produced a lovely friction-powered, wheeled spherical orange tin. ‘Man Made Satellite’ now resides in the collection of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood.

It was not simply because Star Wars shifted such enormous volumes that it changed the existing action figure model; it was because that, up until then, the standard height of such toys was 12 inches, the size of GI Joe and Action Man toys. However, because scaling associated space vehicles such as Star Fighters, the Millenium Falcon and X-Wing Fighters to this large size would be impractical, the smaller size of 3 inches was adopted. Consequently, manufacturers such as MEGO in the USA and Palitoy in the UK were forced to scramble to produce similarly-sized figures for some of the properties they owned. In the UK, Action Man was quickly transformed into the much smaller Action Force range.

Ideal’s Kerplunk board game first hit the shops in 1967.

Produced between 1967 and 1975, Jay West and his brother Jamie stood 7.5in tall and came with a range of vinyl accessories. Collectors should note that their moulded caramel-coloured plastic bodies tend to suffer from fatigue and stress fractures.

Clackers were the craze amongst children in the early 1970s. After swinging these hard plastic balls up and down and violently banging them together, the injuries caused resulted in them being taken off the market.

Once Star Wars had proved that toy merchandising could be a treasure trove, other movie and television producers joined in the gold rush and soon names like Batman, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The Avengers, Transformers, Spider-Man, Toy Story, Harry Potter and, most recently, Frozen, saw their toy spinoffs hit the big time too.

I began this chapter revealing that I was part of the Baby Boomer generation, proud that I grew up at a time when youngsters could enjoy robust playtime out in the open air and constructive games and hobbies in their own homes. All innocent fun, despite the possibility of imminent nuclear destruction if the superpowers fell out irrevocably and ended all that fun in a blinding flash.

All the rage, American comics promised childhood fun we British could only dream of.

It is a cliché, but true, that nostalgic memories of childhood are often rose tinted and that sometimes we remember only what was good, whilst forgetting the bad times. This way of thinking is not new: even the ancient Athenians felt that their society had declined from its former mythical Golden Age when Pericles promoted the arts and literature and helped Athens acquire a reputation for learning and culture.

I think childhood is better today. Health care, dentistry, and the individual liberties of kids are far better than they were during my childhood.

I am encouraged that children still play with toys and enjoy all sorts of hobbies and arts and crafts and, despite coming from a family in which my predecessors routinely served in the armed forces, I am genuinely pleased that teenagers do not have to undergo national service in the military.

Although some famous names from the past including Tri-ang, Louis Marx, Spot-On, Dinky Toys, FROG, Husky and Tommy Gunn – to name but a few – are no longer with us, it warms the cockles of my heart to know that Hornby, Airfix, Scalextric and Corgi, names with which I was familiar over 60 years ago, are still very much around.

In 1966, the author’s parents bought him this Dinky Toys Beechcraft Bonanza from Heathrow Airport before they travelled to their new home in Hong Kong.

STAR WARS

Science-fiction toys really hit the big time following the release of George Lucas’ seminal