11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

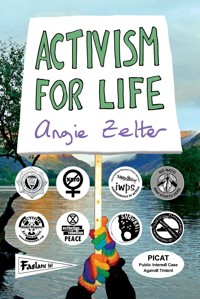

For over four decades Angie has campaigned for a greener, fairer and safer world. This remarkable account of her campaigning life shares some of the lessons she has learnt from her actions in many different countries. Heartfelt but clear, it includes personal insights into mobilising for effective, sustainable actions, dealing with security, police and courts and how seemingly different issues are actually closely intertwined. This unique book covers nuclear weapons, militarism, climate change, corporate abuses of power, environmental destruction and much more.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 444

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ANGIE ZELTER has been an active campaigner for most of her life. She has designed and participated in nonviolent civil resistance campaigns and founded several innovative and effective campaigns. Her protests have been for a nuclear free world, that shares global resources equitably and sustainably while respecting human rights and the rights of other life forms. As a global citizen she has expressed her solidarity with movements all over the world. This has led to numerous arrests, court appearances and incarceration. Angie has been arrested around 200 times, mostly in the UK, and in Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Gran Canaria, Holland, Israel/Palestine, Malaysia, Poland and South Korea. She has spent over two years in total in prison awaiting trials on remand or serving sentences. All for nonviolent resistance protests. The author of several books, she is the recipient of the 1997 Sean McBride Peace Prize (for the Seeds of Hope Ploughshares action), the 2001 Right Livelihood Award (on behalf of Trident Ploughshares) and the Hrant Dink Prize in 2014. She continues to actively confront the abuses of corporations, governments and the military.

It has been one of the privileges of my life to be with Angie as she stands up for justice, peace and the environment. She personifies what being an activist means – courage, commitment and a conscience. She’s an inspiration to us all.—CAROLINE LUCAS MP.

Angie Zelter’s lifelong commitment to her campaigns and PICAT [Public Interest Case Against Trident] legal actions have been a major force towards nuclear disarmament and informing my own conclusion that we should say ‘No to Trident.’—COMMANDER ROBERT FORSYTH, ROYAL NAVY (RETIRED)

With decades of experience of local, national and international campaigning on many of the key issues of our time Angie Zelter has distilled an extraordinary amount of determination and learning into an absolute gem of a book.—PROFESSOR PAUL ROGERS

Front cover photo, Lake Padarn by Snowdonia in Wales: Hefin Owen (cc) via Flickr

A prophetic voice from the frontline of nonviolent activism, Angie’s book is a riveting account of what it really means to practice the conviction that there is no way to peace, because peace is the way. And though she is probably best-known as a passionate campaigner against nuclear weapons, which is where so many members of the Iona Community have encountered her, her belief that ‘human rights, land rights and indigenous peoples’ rights are all part of our struggle for a more just, equitable, peaceful and truly democratic world’ has taken her to stand with defenders of life on earth in many places and situations. Her practical experience and wisdom, hard-won over a lifetime, make this an invaluable handbook for a new generation of activists committed to a better future.—KATHY GALLOWAY, THE IONA COMMUNITY

Dyma lyfr sy’n gweld y cysylltiad rhwng pob achos dyngarol - rhwng heddwch a chwarae teg, rhwng cymdeithas wâr ac amgylchfyd iach, rhwng hawl i siarad iaith a hawl i fyw heb ofn trais. Mae Angie Zelter yn myfyrio dros oes o ymgyrchu dros y pethau hyn gan rannu cyngor a phrofiad. Trwy’r cyfan mae’n cynnig gobaith ac ysbrydoliaeth, ac yn ein hannog i wneud beth bynnag sy’n gymwys i ni fel unigolion i wella amgylchiadau’r byd a’i bobl. Y pwythau sy’n rhwymo’r penodau at ei gilydd yw’r tri gair bach, mawr: ‘Never give up!

This is a book that will fill you with awe and admiration, suspense and surprise, but above all, it will offer inspiration and hope. From the mundane grind of letter-writing to daring adventures the world over, Angie Zelter reflects on a lifetime of campaigning for a fairer, better society. She shares advice based on real-life experience – what went wrong, what worked – and in the way she recognises that it will take action of every description to bring peace to the planet, she encourages us all to think about how we too can contribute to this goal. The book chimes with phrases that are sometimes practical, sometimes aspirational, always encouraging. The thread that stitches the pages together is three words long: ‘Never give up!’—PROFESSOR MERERID HOPWOOD, OUTGOING CHAIR OF CYDEITHAS Y CYMOD (INTERNATIONAL FELLOWSHIP OF RECONCILIATION, WALES) AND VICE PRESIDENT OF THE MOVEMENT FOR THE ABOLITION OF WAR)

She did not hesitate. She just walked along the Gureombi Rock coast fenced for the Jeju navy base construction. And it was a while later that we discovered Angie with her bright smile inside the fence with the policemen in the background. 10 days later, the Gureombi Rock began to be blasted. The struggle to save the Gureombi Rock coast had reached its peak. Angie stayed with us for a month and was arrested three times for her nonviolent direct actions. When a Korean policeman inquired about her name, she said it is ‘World Citizen’ and about her nation, she said she came from Gureombi. In her last arrest, she got an exit order. She left us a gift of a flag with an image of the Earth without any artificial nation borders. It is not only me but many people in Gangjeong who have been greatly affected by her legacy. After her visit to Ganjeong, she is one of our greatest inspirations to keep us fighting against this base.—CHOI SUNG-HEE, GANJEONG VILLAGE RESIDENT/PEACE ACTIVIST

Books by the same author:

Snowball: The Story of a Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Campaign in Britain (ed with Oliver Bernard), Arya Bhusan Bhardwaj, 1990

Trident on Trial: The Case for People’s Disarmament, Luath Press, 2001

Faslane 365: A Year of Anti-nuclear Blockades, Luath Press, 2008

Trident and International Law: Scotland’s Obligations (with Rebecca Johnson), Luath Press, 2011

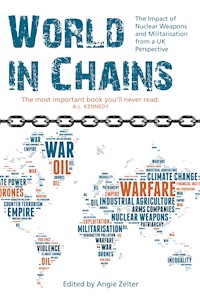

World in Chains: Nuclear Weapons, Militarisation and Their Impact on Society (ed), Luath Press, 2014

First published 2021

eISBN: 978-1-910022-52-8

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Images © Angie Zelter unless otherwise stated.

© Angie Zelter 2021

Dedicated to all living beings on planet Earth at this crucial time of change.

To the humans among us – let’s remember we are global citizens.

We either go forward together to a more equitable, fair and compassionate global society or we will destroy ourselves and our once diverse home.

Let us all join our hearts and minds and act in the interests of all life forms.

We know the solutions – let’s act now.

Contents

Preface

Foreword by Kate Dewes

Foreword by Alice Slater

1 The Beginning: Cameroon, Sustainable Living and Greenham

2 Carrying Greenham Home to Norfolk and the Snowball Campaign

3 Building Networks of Resistance at Home and Abroad

4 Preparing and Following Up Actions

5 Reclaiming International Law and Making it More Accessible

6 Legal Challenges

7 International Solidarity

8 Continuing the Struggles Worldwide

9 It Never Ends

10 Police, Prisons and Hot Springs

11 Linking Our Struggles in One World

12 Lessons Learnt

Answering Questions from a Young Activist

Timeline

APPENDIX 1: NONVIOLENCE

Appendix 1a: The Nonviolence Movement

Appendix 1b: Gandhi’s Seven Sins of Humanity

Appendix 1c: Campaigning Skill Share, May 2010

Appendix 1d: Example of Police Liaison Letter from the Trident Ploughshares Core Group, 2000

APPENDIX 2: NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW

Appendix 2a: Judge Bedjaoui Statement of 2009

Appendix 2b: The Right Livelihood Awards 2001 – Acceptance speech by Angie Zelter, 7 December 2001

APPENDIX 3: ARMS TRADE

Witness Statement of Angie Zelter at trial in January 2018 for the DSEI 2017 blockade

APPENDIX 4: MILITARISM

Appendix 4a: Eighth Report from Gangjeong, 16 March 2012

Appendix 4b: Nonviolent Resistance to US War Plans in Gangjeong, Jeju Island. Article by Angie Zelter, 6 April 2012

APPENDIX 5: PALESTINE

Appendix 5a: ‘Spring in the Countryside’. First of the IWPS-Palestine Occasional Reports from Angie Zelter in the West Bank, 22 March 2004

Appendix 5b: Lessons Learnt by The International Women’s Peace Service – Palestine. Talk by Angie Zelter, 8 August 2008, London

APPENDIX 6: FORESTS

Response to 15 August 1991 Borneo Post article ‘Environmentalists Declare World War on Malaysia’ written by Ms Angela C Zelter on 20 August 1991 in Miri Jail, Sarawak

APPENDIX 7: CLIMATE CHANGE

Witness Box Statement at Extinction Rebellion Trial – Angie Zelter, Hendon Magistrates’ Court, 25 June 2019

APPENDIX 8: WOMEN

Women, Peace, Security and International Solidarity – A short presentation by Angie Zelter, given at the FMH, Edinburgh as part of the World Justice Festival, October 2017

Further Reading

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Preface

OVER THE YEARS I have often been asked to reflect on various actions or events that I have taken part in. So, when I was invited to Gothenburg in Sweden in 2010, I delivered a talk which encapsulated some lessons for lifelong activism. I later developed these as a slide show for Bradford University in 2015. The ‘lessons’ proved of great interest to the people who heard them and I was asked to write down more of my experiences.

This book builds on these lessons, and is an attempt to reflect on some of the campaigns and actions I have been involved in. It covers campaigns and movements that include the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, the Snowball Civil Disobedience Campaign, SOS Sarawak, the UK Forests Network, the Citizens’ Recovery of Indigenous Peoples’ Stolen Property Organisation, the Seeds of Hope Ploughshares, Trident Ploughshares, the International Women’s Peace Service – Palestine, Faslane 365, Save Jeju Now, Action AWE, the Public Interest Case Against Trident and Extinction Rebellion Peace.

It is 50 years since I left university, started my real education and began thinking about how I could help create a better world. This is the story of my personal journey to make sense of a world that I knew was teetering on the edge of self-destruction. Instead of despairing and becoming a part of the problem, or just putting my head in the sand and ignoring it all, I wanted to find ways to change the age-old patterns of exploitation, power abuse and fear that were fuelling the nuclear arms race, environmental destruction and ecocide on our planet. That meant changing my lifestyle and learning from past nonviolent struggles against oppression.

These recollections focus on my campaigning life and show how an ordinary woman like myself chose to respond to some of the most serious and challenging issues of my era. The Appendices contain documents and reports which provide extra information on nonviolence and solidarity campaigning.

Angie Zelter February 2021

Foreword by Kate Dewes

Kate Dewes ran the South Island office of the Aotearoa/New Zealand Peace Foundation from 1980 and has co-directed the Disarmament & Security Centre1with her husband Robert Green since 1998. She was a member of the Public Advisory Committee on Disarmament and Arms Control for nine years; the New Zealand government’s NGO expert on the UN Study on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Education 2000–02, and a member of the UN Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters 2008–13.

AS A FELLOW woman peace activist committed to nonviolent direct action, my anti-nuclear campaigning in New Zealand began during the mid-1970s Peace Squadron actions. In small boats we confronted US and UK nuclear-powered and probably nuclear-armed warships visiting our ports. We used these spectacular confrontations, attracting extensive national and international media coverage, to help generate hundreds of grassroots peace groups, which led to our iconic 1987 nuclear-free legislation banning these warship visits.

My first contact with Angie Zelter was during the decade-long World Court Project, pioneered in Christchurch when, as Secretary of the UK Institute for Law and Peace, she distributed information about the international laws of war. She also established the Snowball Enforce the Law Campaign which involved arrests, court cases and imprisonment. This followed her first arrest during the early 1980s women’s occupation of the US base for nuclear-armed cruise missiles at Greenham Common. Women returning home to young families and other responsibilities were encouraged to ‘think globally, act locally’, and ‘Carry Greenham Home’ to highlight the issues at local military and intelligence-gathering bases. Globally, women’s groups protested in solidarity with the Greenham campaigners.

The various campaigns Angie initiated often used creative, courageous, sometimes humorous and colourful actions to uphold international law over national legislation. Media attention raised public awareness about the issues. Her campaigns challenged deeply entrenched UK government practices and reliance on public deference to authority. She even had the principled audacity to write a DIY Guide to Putting the Government on Trial in an attempt to get the courts to outlaw British nuclear weapons. Her careful preparation of documents and uniquely inclusive campaigning skills attracted support from sympathetic lawyers, and her actions advanced the many different causes she espoused.

Like Gandhi and other nonviolent peace leaders before her, Angie represented herself in court, enabling her to say things traditional lawyers could not. She demanded that legal proceedings were accessible to ordinary people and were conducted in plain language. While in prison, she agitated successfully for improved hygiene and conditions for women inmates.

This memoir of her life as a dedicated anti-nuclear and environmental campaigner highlights lessons learnt from her extraordinarily diverse experiences. In effect it is a most valuable handbook for all campaigners, especially young people, on how not to waste energy on ineffective protest for its own sake. She learnt that

effective campaigning needs sustained nonviolent direct action combined with education of the public, lobbying, negotiating and… it needs clearly communicated requests or demands that can be implemented by the people or organisations targeted.

Angie’s seemingly inexhaustible energy and zeal are balanced by extraordinary humility as she follows the thread of her many courageous actions sustained over half a century. She gently encourages us to ‘take each step in good faith and learn and adapt as you go along’, ‘set a time limit on each action’ to prevent burnout, and above all remember: ‘it is better to try and fail than not to try’ to do what we can to change the world.

Foreword by Alice Slater

Alice Slater serves on the boards of World Beyond War, the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space. She represents the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation at the United Nations and works with the People’s Climate Committee, NYC, working for 100 per cent green energy by 2030.

AT A TIME when our whole world is so painfully experiencing the murderous excesses of patriarchy and untrammelled capitalism, with the very existence of humanity threatened, Zelter’s experiences demonstrate how any one of us can make a difference and be effective in ending bad policies and building a better world.

She relates a moment in her life when her eyes were opened to the major crises facing life on Earth, and from then on, it seems like there was just one thing after another in a lifetime of working for a better world. She starts out in Cameroon as a newly-wed, where she observes the dehumanising and oppressive system of British colonialism, returns to the UK where she joins up with the women of Greenham Common to protest nuclear war and the missiles stationed there and continues by engaging in all forms of nonviolent protests, being arrested many times over the years. She writes powerfully about how she challenged the prison system and revealed to the world the terrible conditions that existed in jails, particularly how women were affected. She publicised the folly of the law and the legal system that protected the military installations. She learnt how to organise and broaden community organisations which could engage the media, the press, the legal structures: all to get the word out and move public opinion.

Her activism led her from campaigns within the peace movement to ban the bomb, to working with environmental groups in Malaysia and Canada publicising the truth about forest destruction and the great injustices done to indigenous people who were trying to save their forests from corporate greed and relentless consumerism. She has worked and been arrested providing support and solidarity with Palestinians in the rural communities of Salfit suffering under the harsh illegal Israeli military occupation of the West Bank. She ends with the wonderful new generation of climate activists in the UK’s Extinction Rebellion organising trying to stave off catastrophic climate disaster.

Undaunted, Zelter continues her work for a liveable Earth. She reminds us that any one of us can do it and has written some inspiring rules for engagement. Her passionate and persistent energy devoted to peace and justice is a shining example that we can all be a part of this. If you ever needed a good shot of political will, to encourage you to add your voice and your efforts to the work that lies ahead, read Activism for Life and get organised! Zelter’s inspiring book reminds me of the famous aphorism from Margaret Mead, which illustrates the principles and encouragement Zelter provides:

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has!

1

The Beginning: Cameroon, Sustainable Living and Greenham

I WENT TO Reading University to study Philosophy and Psychology. In 1972, my final year, I read the special edition of The Ecologist magazine called A Blueprint for Survival.2 It was an eye-opener, as it introduced me to the major problems then facing our world – war, poverty, acid rain, ozone depletion, desertification, species loss, deforestation, greenhouse gases, civil and military nuclear power, pollution, endless economic growth and consumerism. I was astounded that having gone through a university education I had never come across most of these issues before. I realised that I was incredibly ignorant, and had to start taking responsibility for my own education by reading more widely and mixing with a greater variety of people. I had to question the dominant Western culture and open myself up to informal and alternative learning methods. As I read and thought more deeply about the crises facing life on Earth, I knew that I wanted to be a part of finding their solutions. On hearing of any problem I always want to be involved in finding out if there is anything I can do or change that will make the situation better. I cannot just forget it.

After my degree, at the age of 21, I decided to do some voluntary work in Africa with my husband. We spent three years in Cameroon, where I had the first of my two children and learnt lessons that have remained with me to this day. I was shocked to find that colonialism and racism still existed. Yes, I was very naive and ignorant. I still remember my shame and embarrassment when we held our first party one evening a few months after we arrived. The women were at one end of the room, the men at another, the white-skinned people on one side and the black-skinned on the other. The white expatriates (our neighbours) stayed on much later and started expressing their racist views and I could hardly believe what they were saying, nor could I hold back my tears.3

Expatriates like us were expected to have servants, which we refused to do, and that decision was criticised by our fellow expatriates. But I wanted to have a more equitable relationship with local Cameroonians and hated the idea of a servant/boss relationship. In any case I have always believed that people who are able to, however busy and important, should keep in touch with reality, do their own dirty work and look after their own daily needs. It is important to be as independent as possible.

It was quite funny to see the reactions when some of our Cameroonian friends came to visit and found my husband on his knees cleaning the floor. It was also very difficult at first to persuade Peter, a local banana plantation worker, who later became our best friend, to call us by our first names rather than Sir and Madam. We let his younger brother live for free in the ‘servants’ quarters’ that were provided with each house in the government residential area where we lived, and we became very close to other members of his extended family.

I soon discovered that local land had been taken over by the UK and French governments and companies for timber, palm oil, rubber, banana, tea and cocoa plantations. I saw poverty in a land of plenty and began to understand the inequities of international trade. I also soon realised that volunteers got a lot more out of their stay than they were able to give to the host communities. The huge disparity between the wages that we expatriates received and those that locals received was shameful. We soon got an insight into the life of local people when we took a walk through the nearby village and got talking to Peter, who worked planting and caring for the bananas at a nearby plantation.

As the months went by we visited him frequently, and his oldest daughter was often sent by her mother to ask for sugar or tea or other foodstuffs that they were too poor to buy. Peter spent time with us at the weekends, taking us to meet his friends in other villages nearby, often to traditional ‘elephant dances’ where there was a great deal of dancing and singing, drinking of palm wine, and where newly-born infants were blessed by the spirits of elephants. He also took us up Mount Cameroon to explore the cloud forest and black lava fields where we could collect wild honey.

It was here in the forests of Equatorial Africa (from mangrove swamps, to tropical rainforests to cloud forests) that I came to passionately love trees and birds. The diversity was astounding. Once I looked out of the window and saw five different kinds of kingfisher, including the tiny pygmy kingfisher in beautiful blue, red and white. Later, while at the coast far below the town of Buea, where I lived, we saw the black, white and tan giant kingfisher along with sea snakes and an amazing view of the island of Fernando Po on the sea’s horizon, which is usually hidden by sea mists but had suddenly emerged to look like a reflection of Mount Cameroon.

During my first year in Buea I was asked by a local man why I had come to Africa and I replied that I had come ‘to help’! I was told very clearly that if I really wanted to ‘help’ Cameroon or any of the poorer countries of the world then I should go back home to the UK as that was where the problems originated. This really got me thinking. I realised it was too easy to think of the ‘poor’ people in ‘third world countries’ (as they were then called) and to look no further than the poverty, ignorance and local corruption. There was corruption, of course, as there is everywhere. But it was too easy to look at ‘their’ problems and issues and ignore the structural and global inequalities and corporate corruption underlying the realities of under-development. There was a need to understand the consequences of resource extraction and destruction of the environment caused by corporations and governments far away. I found that it was true that the majority of the problems faced by ordinary people in West Africa were caused by foreign powers and corporations extracting the oil, minerals, fish, timber and food from the land and seas. The extraction resulted in no gain for local people but in fact impoverished them and their environment, preventing them from developing themselves. My time in Cameroon resulted in my realising that the majority of my life’s work would have to be dedicated to trying to stop my own country exploiting the resources of other peoples’ lands.

Cameroon is an amazingly diverse place, geologically, culturally and linguistically, with over 250 languages. These languages are quite distinct and seem almost to change from village to village. Most locals that I met could speak up to ten of these different languages as well as Pidgin English. While there, I read widely about African history, the slave trade and often talked to the students at the Pan-African Institute for Development where my husband was teaching. They were mainly middle-level civil servants from anglophone African nations with a great deal to say about development issues.

While in Buea, I used to go to the local market and buy all the books in English in the African Writers Series, devouring the fascinating novels of Chinua Achebe, Camara Laye, Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri and many others. My mother-in-law had been born in Southern Rhodesia and my father-in-law had settled there when he was 21 years old.4 They were very involved in supporting the Black independence movement. They were visited by many British historians while living in Salisbury and got to know Basil Davidson very well.5 So of course, I read his books on the history of Zimbabwe. I still have a signed copy from him of his Black Mother: The Years of the African Slave Trade.6

When UDI (the Universal Declaration of Independence) was declared by the white regime under Ian Smith, people of their persuasion were likely to be rounded up and imprisoned. The family therefore moved to Northern Rhodesia, which was now happily independent and renamed Zambia. Their knowledge of African politics and the iniquities of British colonialism were very informative. When our three-year contract came to an end, I was carrying my second child and we had to decide whether to stay on in Cameroon or go home. We decided that it was time to return to the UK and put into practice our desire to live more sustainably, and try to stop the worst excesses of British companies and corporations that had continued the British contribution to the under-development and exploitation of Africa.

Returning to the UK in 1975, I moved to Norfolk with my two children, husband and parents-in-law. We were an extended family of six people and it was especially good for the children to have different role models. We were determined to live as sustainably as possible, keeping bees and chickens and growing fresh fruit and vegetables organically. I was fascinated to learn about the myriad soil organisms and read The Living Soil.7 I soon got involved and helped start a local Norfolk-based joint Soil Association and HDRA (Henry Doubleday Research Association) group and still buy my organic seeds from Garden Organic which was founded by Lawrence D Hills.8

This was a special time for me with the children growing up, spending lots of time with them and growing food in our large garden. I had the extraordinary good fortune to meet and talk to the co-founder and first President of the Soil Association, Lady Eve Balfour, at Haughley, where I spent some time cataloguing her library.9 At dinners with us volunteers she presided over fascinating talk around the table where everyone listened to each other. It felt so civilised and inclusive, and I was introduced to many of the classic organic books. I was especially impressed with Farmers of Forty Centuries, which explained how one could continue to grow food on small plots of land for centuries if you looked after the soil and recycled all waste back into the land.10

My concerns about how we produce food sustainably have stayed with me. I learnt to make and sell pottery and cane chairs, and my husband made beautiful hand-made furniture and taught the violin and cello. The children were lucky to have their grandparents living with them, as were we. We had lots of their friends visiting us at the weekends, many of whom were, as you would expect, from southern Africa. But we also had guests from other parts of the world, as my father-in-law was Romanian and my father was Armenian and my side of the family had moved to live in Vienna in Austria.11 So we had a diverse group of people coming in and out of our home, enriching our lives with their different stories. Some people stayed for weeks and months at a time in our large house set in an acre of land, close to the sea and with our nearest neighbour over half a mile away. The creative and life-affirming practical work within a loving family sustained me over the following years of political activism, helping me avoid major burnout.

One of the books that influenced me and many of my generation was Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered.12 This, along with other books discussing growth economics and capitalism, sparked my interest in economic structures which continues to this day. It seemed that whatever problems I was looking into, the economic structures were holding everything back. Much later on I met Mary Mellor who taught me a great deal about the creation of money and how the banks create it out of thin air from debt (much of it from mortgages) and how it could instead be created on credit by the government and used in the public interest.13 I now follow the admirable work of Positive Money, a group that educates and advocates for a money system that works for our society as a whole.14

We had returned home during the height of the Cold War and nuclear weapons were a major issue. I soon got involved in the peace movement and helped co-ordinate the local Cromer Peace Group, collecting signatures for the first World Disarmament Petition, supporting demonstrations, leafleting and vigils.

My very first arrest was in 1983 at RAF Greenham Common, where nuclear cruise missiles were to be based.15 These ground-based cruise missiles, deployed all around the country on the backs of lorries, threatening nuclear war, were depicted by the artist Peter Kennard in ‘Haywain with Cruise Missiles’. We had no legal briefings or workshops. We just joined hundreds of other women, sitting in front of the gates and blockading, cutting the fences and entering the high-security areas. I used to go for weekends and get in and out of the base as many times as I could.

The court cases were amazing. Women of all ages, classes and beliefs stood up and represented themselves. Polite women explaining why they had broken the law in a very articulate and quiet manner, poetic women reading their verses or singing in court, silent women, angry women, screaming, despairing women, some breaking the rules of the court and refusing to stand for the magistrates’ entrance, some defying the court and lecturing the judiciary on the ills of nuclear weapons, some praying and some dancing, all of them being found guilty and many being led away to prison straight away for contempt of court or for refusing to pay fines.

The resistance was wonderful, funny, poignant, empowering and I discovered that there is no ‘right’ way to protest or resist or defend yourself. Each person must find their own voice: diversity is empowering and a strength in itself. From this time onwards I have almost always represented myself in court and refused to pay fines, and have tried to make sure that the legal system is challenged to be as accessible to everyone as possible.

My brother, at that time, was a policeman in the RAF, and because of the hundreds of women getting into the Greenham airbase he was likely to be deployed there, as the authorities tried to have guards every few yards around the perimeter fence to prevent our incursions. This took hundreds of personnel, so different units were brought in for short rotations, but it was not very effective because we were so many. We managed to get into the base anyway, because as one woman cut the fence in one spot and started to crawl through, lots of the inside guards would crowd around, leaving their posts, so other women could cut the fence and get in at the places they left. The police and guards deployed outside the fences often sat in their cars, so some of us used to talk to them while other women were carefully letting their tyres down, then we would all run off.

Some of it was not so amusing when the authorities deployed the SAS and other troops to try to get rid of us and there were some nasty incidents when red-hot pokers were put through tents and shelters where we were camping, when our fires were put out in the middle of winter with water hoses, when our possessions were stolen and we were abused. But it is amazing what women can do when they work together and support each other, and lots of donations arrived from women who could not come and camp, or who came just for a few hours to keep the camps occupied while others went off cutting fences or doing court support.

My brother came to visit me at home at Valley Farmhouse with some of his RAF friends, and when I asked him what he would do if he saw me inside the high-security areas at Greenham, he said he would shoot me, as those were the orders! We decided that we would make sure we would not be there at the same time.16

Around the camp fires at the women’s peace camp were truly times of sharing, swapping stories and learning from each other. We discussed the meaning and the importance of nonviolence, of non-hierarchical ways of making decisions and working together, feminism and women’s power. We discussed the whole nuclear chain, from mining, production, testing, deployment and use, the impact of all this on people local to the mining and testing sites and especially on indigenous peoples. We thought about weapon systems, the arms trade, geopolitics, racism, poverty and most importantly how to get the UK to stop deploying cruise missiles. We realised that everything is linked. Go into any one issue deep enough and you will find how it connects with another.

We also shared food and songs. So much music and creativity helped us get through the tough times. Many songs were composed and shared around the camp fires. I chose to be at Orange Gate most of the time because of the music.17 I could only go for a few days at a time as the children were still young but they were being well cared for, and they often came with my husband when he dropped me off at the camp so they could see where I was staying and meet some of my friends.

I thoroughly enjoyed the freedom and creativity of working in a women-only environment for the first time. Many women told us how they were now able to speak freely and really be heard, that in mixed-sex groups their suggestions and comments were often ignored. They might say something that was not acknowledged or discussed, but if a man said the same thing a little later, it was listened to. Many women, myself included, were not as confident speaking up in front of large groups: they preferred face-to-face or small groups where it felt easier to say what they thought. This was why men often dominated in larger groupings or more formal settings. Of course, there were also many women turning up who had been badly abused by men and only felt safe in this women-only environment. There was a great deal of listening and support going on. It was a special time, an experience of a very different culture building up. A song spoke to this – ‘Shall There be Womanly Times? Or Shall We Die?’.

I was arrested many times at Greenham, but only one of these resulted in a court case as generally the police and courts could not deal with the hundreds of arrests taking place each month. We mostly just had our details recorded, were escorted out of the base and heard nothing more.

2

Carrying Greenham Home to Norfolk and the Snowball Campaign

MY SECOND ARREST, the one that resulted in a court case, was in 1984. A group of us from Norfolk chained ourselves to the House of Commons railings with banners against nuclear weapons and refused to leave. We were a small group of around five people, and had decided we would not give our real names when we were arrested unless we were assured we could use international law in our defence. I had been interested in international law ever since hearing about the war laws and it seemed important to be allowed to talk about these in our defence.

We decided on various false names and I chose Winnie Mandela.18 I did not realise that this ‘alias’ would continue to haunt me for the rest of my days! So if you choose an alias, make sure you will be happy with it for your lifetime. We had not decided many details before our action, and we were soon carted off to police cells and kept apart so we could not communicate with each other. I explained that my name for the day was Winnie Mandela and that I would not give my real name until the court agreed to an international law defence. The police were not interested at all. They just kept me in the police cells and asked me for my name each day. After the first day, they told me that my colleagues had already given their names and had been released on bail. I did not believe them. After seven days, I realised we had made a big mistake – we had not agreed a finish time! Another lesson learnt and never forgotten: in all your action planning, make as many contingency plans as you can and agree an ending time. However, one only gains experience by making mistakes, by acting and finding out the consequences, and this lesson was very useful.

I decided at last to give my real name and was bailed to appear in court later. I learnt on my release that three of the others had given their real name after only a few hours in the police cells, and that one other person had stayed inside for a couple of days only. I was the only mug to stay inside for a week!

However, I had found out a great deal about how to cope in custody and about the overcrowded police cells. I listened to lots of other prisoners (many of whom were high-class prostitutes) talk about which judges took prostitutes and which took drugs. I saw police officers call some of the women out, who then returned with take-away food after having ‘serviced’ the men. I received an insight into the hidden world of police custody, a system I knew little about. I also found out how boring it could be, locked up in a small space day after day with little to do. Time spent in police cells is much more difficult than time spent in prison. I never again went into an action without several books to read and a clear agreement of when or under what circumstances we wanted the action to end – not that this would always be in our control.

The ’80s were busy years for the anti-nuclear peace movement, but I needed to be with my young children and it was quite a long way to Greenham Common. There was a banner on the fence that said ‘Carry Greenham Home’ so I decided to do just that, and work nearer at home in north Norfolk.

Thousands of people all over Britain were not only frightened by nuclear weapons but also wanted to do something about it, to take responsibility in some way, and they wanted to do this locally. I was a member of a local peace group and had already organised a few demonstrations in my rural north Norfolk area. It was not very densely populated, was very conservative and full of RAF bases, many of which were actually US bases in all but name. I thought long and hard about what to do, and in 1984 founded and co-ordinated the Snowball Civil Disobedience Campaign to try to persuade the government, by totally nonviolent means, to show that they truly wanted peace by committing to at least one disarmament measure.19 It was intentionally designed to include men as well as women as I aimed to include the many men wanting to take action, feeling excluded by the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp but who had not found the energy to start their own campaign or camp around the other numerous nuclear bases.

Britain at that time was characterised as a US aircraft carrier and Liz, a nearby artist friend living in Aylsham, sewed a banner with an outline of the shape of the UK with a huge US flag behind it, several US planes flying over the UK and words saying ‘Whose Britain?’20 I decided that the civil disobedience act should be simply cutting one single strand of wire around the fence of my nearest US military base (USAF Sculthorpe). Cutting a single strand was to limit the amount of damage done and to be perceived as purely symbolic from an individual’s point of view, unthreatening in a physical way to the authorities, but serious enough to warrant prosecution under the Criminal Damage Act and for the authorities not to be able to ignore it. We would be able to explain our actions in the courts and bring the issue of nuclear devastation into the limelight.

As a first step I had to find two other people to join me in cutting the fence at Sculthorpe. These two people were hard to find, but eventually I persuaded a friend, Tony, and my mother-in-law Dorothy to join me. And I was given a valuable piece of advice from an older Quaker friend whom I had approached to take part. He said no, such action was not for him as he did not think cutting fences was a good way to change people’s attitudes, but that if I still thought the action was worth doing I should do it anyway even if no one else joined in – I should follow my spirit and act in the truth of that spirit. This has been something that has stood me in good stead – to think of the real value of an action rather than how popular it might be.

It was difficult to find colleagues in the peace movement at the time to take part in this first action, as it seemed to be encouraging vandalism. Although what we were doing was open and accountable and very symbolic with the cutting of only one strand of wire in the fence surrounding the US base, nevertheless it would be considered as ‘criminal damage’ and we were likely to end up with a criminal record.

I had also stipulated that we each write a statement of intent explaining why we were doing it, to clarify for ourselves our motivations and reasons, and be ready to hand the statement into the police and courts. We also had to commit to write to three public figures explaining our actions and to find two more people to join us in a month’s time for the next stage of the Snowball, so that it would grow. The campaign was designed to encourage communication and dialogue and was linked with three requests for the government to take achievable steps towards disarmament. We said we would end the campaign if the government took one of these steps, and it did come to an end when the government signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at the end of 1987.21

The Snowball campaign sparked a whole debate that was new to most people at the time, about whether destroying or damaging property was nonviolent or not – with vociferous local public meetings that included local MPS and the press. Our argument was that it depended on the spirit in which the destruction was done and what was being destroyed and why. For instance, destroying a front door to rescue a person inside from a fire would not be considered as wrong because it was to save a life. Similarly, our actions were to save lives.

The Snowball started with three of us, accompanied by the press, openly cutting our strand of wire at USAF Sculthorpe, and was then supposed to triple at each stage a month apart and take off! When the second stage took place with nine of us, the police started taking bets about how long it would take to peter out. A month later we had our 27, but then the next month we could not quite make the 81. So, I learnt something else: don’t make things difficult by setting impossible goals, life is not tidy like a game. And, when things don’t work out as planned, improvise, admit a mistake, adapt and continue the campaign in another way.

So we spread the idea to other us bases and snowballed horizontally instead of vertically.22 We made it easy for people to join in by writing a pack and sending it out so people could copy the idea and do it at their own local US base. One of our slogans was ‘Don’t sit on the fence. Cut it!’. We circulated reusable envelope stickers with this slogan on. We worked hard getting national celebrities and well-known figures to come and cut a strand: these included Lord Peter Melchett, Countess Dora Russell, Billy Bragg and Bruce Kent. But of course, there were also lots of local well-known figures who supported us too.

The local courts and papers were full of it all as so many people got involved and had to appear in the local Fakenham Magistrates’ Court. The court was reported to be having its longest hearing in its history when 50 of us were tried over a two-week period in February 1986.23 Usually, the little court only met once a week with local magistrates, and they had had to call in a stipendiary magistrate from London. I remember it was an amazing community effort with the court being full of people wanting to listen. I had quite a few outstanding cases on during the week and I asked on the first day for reassurance that the stipendiary would not hear cases with the same people involved as this would undoubtedly influence him if he had judged the defendant before. He promised that he would not. But on the next day when I appeared again, he started to hear this second case against me. I reminded him of what he had said yesterday and he ignored me and continued as if I had not spoken. So I just walked out of the dock and into a seat in the public gallery, where I took out a newspaper to read. He then continued to address the place where I had been sitting in the dock and made up answers for me! It was most bizarre and really quite funny. I was learning a lot about the idiosyncrasies of judges and lawyers. The judge gave out quite a few prison sentences, from ten days to three weeks, and so lots of us got experiences of being in prison.24 The local papers had articles about why all these ordinary local folk were going to prison and covered the issues surrounding nuclear weapons.25 I ended up with ten Snowball cases and served sentences totalling 64 days in total, including six days for ‘contempt of court’ when I refused to co-operate by sitting at the back of the court. But I also won a case, getting an acquittal at the only Snowball jury trial held in a Crown Court.

The Snowball spread to Scotland and to Wales, and a World in Action documentary was made of the campaign and shown on prime-time TV.26 I still meet people as I move around the UK who say they were involved in the Snowball campaign and who continue to be active. In the three years it operated we were able to add our voices to the growing tumult against illegal and unethical weapons of mass destruction.

I learnt a great deal from this very first campaign I initiated and ran. It is better to try and fail than not to try: when it is hard to start a campaign but it feels right to you, then do it in the right spirit because it is worth doing in itself and do not worry about whether it takes off or not. Take each step in good faith and learn and adapt as you go along.

And more importantly, I had to learn that although I might initiate a campaign, it was not mine, I did not ‘own’ it personally. I had to avoid the trap of what is called the ‘founder’s syndrome’ – that feeling that I had to be involved in every stage, that I was indispensable. I learnt to reach out and involve others, to ask for help, to make sure that others had the space to initiate, take responsibility and move the campaign on. I learnt to ‘let go’ of the action and thus enable new ‘leaders’, or ‘facilitators’ as we preferred to call them, emerge in other places to co-ordinate the Snowballs in their areas.

I collected lots of the statements that we encouraged everyone to write before their actions to clarify their motivations and to be used in court. Oliver, a close friend and fellow Snowballer, helped me edit them, and I included them in an account of our own history and tried to find a publisher in the UK. But the publishing world at that time was awash with books about peace and disarmament. I was lucky however, when I went to India for a peace conference, that I met AB (Arya Bhushan Bhardwaj) and he published the book on the Snowball campaign in 1989 in Delhi.

I have continued with this pattern of trying to make sure that our campaigns are written up and published. I am so grateful that Gavin of Luath Press approached me when I had finished arguing at the High Court in Edinburgh one day and said he would like to publish a book based on the illegality arguments coming out of the Loch Goil acquittal and the Lord Advocate’s Reference. He has provided incredible support and encouragement and his publishing house has published all the books I have written or edited ever since.27 These books have included contributions from the people taking part in the actions. This is important, because we are all inspired by and learn from each other. We are part of a huge movement for social change and have learnt from those that go before, and others learn from us – we are part of an unbroken line, a continuing tide of resistance that emerges throughout time and place wherever injustice and ill-practice emerge. We need to record our part of the ongoing struggle and explain ourselves, so that our experiences can inform those that come after us and our resistance reaches out into the future. It is our struggle and it is good to explain ourselves in our own words rather than leaving it to others, who may misrepresent us.

This also meant writing articles for Peace News, Disarmament Diplomacy, Red Pepper and other alternative news outlets as well as for the peace movements in other countries. Taking part in conferences and meetings also took up time but was well worth the effort. Communication in different mediums and forums is essential.

By the beginning of 1990 I had been arrested many times and this had led to around 15 court cases, with quite a few imprisonments for non-payment of fines. I was fortunate and privileged to have had the support of my family, who looked after my daughter and son when I was in prison. Living within an extended family made this possible. I am very aware that not everyone has the support to take their resistance so far, which is why it is important to make sure that there are roles and opportunities for people in different circumstances to join our campaigns and offer their strengths and passions.

I had been able to experiment with how far to ‘disobey’ the state and the courts and discovered that it could be quite far. The little local Magistrates’ Court in Fakenham, Norfolk, dealing with hundreds of Snowball cases, had been overwhelmed and was getting annoyed at the number of unpaid fines. The bailiffs were ordered to take my property. My family was rather concerned, so I organised lots of friends and colleagues (about 40 of them) to come to my home one day and Mike, a local blacksmith, acted as an auctioneer and auctioned off all our family property, including our car for 50 pence, my son’s pet snake for 10 pence, the fridge and the washing machine for 20 pence. These were ridiculously cheap prices but we raised a couple of hundred pounds for the Snowball campaign and fun was had by all. Everyone signed a receipt saying they had bought the item, the item had a little numbered sticker put on it, each person signed a receipt which also said they wanted their property to remain at my home until they collected it, and that they would sue anybody who removed this property that was now theirs. It got into the local press and I took all the receipts to the police to make sure the bailiffs were warned that we no longer owned any property. We heard no more about those particular fines.