28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

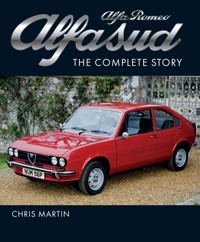

Launched in 1971, the Alfasud was an all-new departure for Alfa Romeo, both in its design and its execution and became the best-selling model in the history of Alfa Romeo . Originally it was developed with the dual intentions of launching the company into large volume production and providing a more affordable model than their highly regarded sports cars. However, its story was far from straightforward. Although respected for its technically brilliant design and universally praised for its ride and handling, the model never quite reached its full sales potential and its reputation was marred by problems that could not have been foreseen. With over 240 colour photographs, the book includes a brief history of Alfa Romeo to the end of the 1960s. The development of the Alfasud's design and the political reasons for building a new factory are given along with the car's reception from both the press and owners. The evolution of the model from initial prototypes, to the improvements to build quality and performance, including the Giardinetta and Sprint variations are covered as well as Alfasuds in competition. The political and labour problems, as well as the early quality control issues are discussed. Finally, there are numerous specification tables, performance data, chassis numbers, engine codes and colour charts. Shortlisted for the 2022 RAC Motoring Book of the Year

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

ALFA ROMEO 105 SERIES SPIDER

ALFA ROMEO 916 GTV & SPIDER

ALFA ROMEO 2000 AND 2600

ALFA ROMEO SPIDER

ASTON MARTIN DB4, 5, 6

ASTON MARTIN DB7

ASTON MARTIN V8

AUSTIN HEALEY

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW CLASSIC COUPES 1965–1989 2000C AND CS, E9 AND E24

BMW Z3 AND Z4

CLASSIC JAGUAR XK – THE SIX-CYLINDER CARS

FERRARI 308, 328 & 348

FROGEYE SPRITE

GINETTA: ROAD & TRACK CARS

JAGUAR E-TYPE

JAGUAR F-TYPE

JAGUAR MKS 1 & 2, S-TYPE & 420

JAGUAR XJ-S THE COMPLETE STORY

JAGUAR XK8

JENSEN V8

LAND ROVER DEFENDER 90 & 110

LAND ROVER FREELANDER

LOTUS ELAN

LOTUS ELISE & EXIGE 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF AND TF

MAZDA MX-5

MERCEDES-BENZ FINTAIL MODELS

MERCEDES-BENZ S-CLASS 1972–2013

MERCEDES SL SERIES

MERCEDES-BENZ SL & NOAKES SLC 107 SERIES 1971–1989

MERCEDES-BENZ SPORT-LIGHT COUPÉ

MERCEDES-BENZ W114 AND W115

MERCEDES-BENZ W123

MERCEDES-BENZ W124

MERCEDES-BENZ W126 S-CLASS 1979–1991

MERCEDES-BENZ W201 (190)

MERCEDES W113

MORGAN 4/4: THE FIRST 75 YEARS

PEUGEOT 205

PORSCHE 924/928/944/968

PORSCHE BOXSTER AND CAYMAN

PORSCHE CARRERA – THE AIR-COOLED ERA 1953–1998

PORSCHE AIR-COOLED TURBOS 1974–1996

PORSCHE CARRERA - THE WATER-COOLED ERA 1998–2018

PORSCHE WATER-COOLED TURBOS 1979–2019

RANGE ROVER FIRST GENERATION

RANGE ROVER SECOND GENERATION

RANGE ROVER SPORT 2005–2013

RELIANT THREE-WHEELERS

RILEY LEGENDARY RMS

ROVER 75 AND MG ZT

ROVER 800 SERIES

ROVER P5 & P5B

ROVER P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

ROVER SDI – THE FULL STORY 1976–1986

SAAB 99 AND 900

SUBARU IMPREZA WRX & WRX ST1

TOYOTA MR2

TRIUMPH SPITFIRE AND GT6

TRIUMPH TR7

VOLKSWAGEN GOLF GTI

VOLVO 1800

VOLVO AMAZON

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Chris Martin 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 909 9

Image credits

Alfa Romeo Museum archives, pages 14, 20, 22, 26, 28 (top and bottom), 29 (top), 31 (top and bottom), 37 (top), 54 (top and bottom), 55, 77 (top and bottom), 86 (top), 116 (top and bottom), 118 (top and bottom), 120 (top left and top right), 134 (top and bottom), 135 (top), 137 (top left, top right, bottom right), 155;Alfa Romeo publicity, pages 6, 19, 21, 24, 29 (bottom), 30 (top left, top right, middle and bottom), 32 (top, bottom left and bottom right), 33 (top, middle, bottom), 34, 35 (top and bottom), 36 (top, middle, bottom), 37 (bottom), 38, 39 (top and bottom), 40 (top and bottom), 41 (top left, top right and bottom), 42 (left and right), 43 (top and bottom), 44 (top left), 49, 56 (top and bottom), 57 (top and bottom), 58 (top left, bottom left, top right, bottom right), 59 (top and bottom), 61, 62 (top and bottom) 63 (top, middle, bottom left, bottom right), 64 (top and bottom), 68 (top right), 74 (top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right), 76 (top and bottom), 78 (top and bottom), 79 (top and bottom), 81 (top and bottom), 95, 96 (top, bottom left, bottom right), 98 (top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right), 99 (top, bottom left, bottom right), 100 (top, middle, bottom), 101 (top left, top right, middle, bottom), 102 (top, bottom left, bottom right), 109 (middle right and bottom), 120 (bottom), 125, 126 (right), 127 (top and bottom), 128, 129, 130, 135 (bottom), 137 (bottom left), 143, 161, 162, 168 (top and bottom), 169 (top, middle, bottom), 170 (left and right); Buch-t/Wikimedia Commons, page 124; carsaroundadelaide.com/Wikimedia Commons, page 121; Lloyd Clonan, page 146 (bottom); Dennis Elzinga/Wikimedia Commons, page 149; Jeremy/Wikimedia Commons, page 148; Magic Car Pics, pages 16 (right), 27, 44 (top right and bottom), 45 (top and middle), 68 (top left), 68 (bottom), 69 (top, middle, bottom), 70 (top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right), 86 (bottom), 87 (left and right), 89 (top and bottom), 90 (top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right), 91 (top), 92 (top, bottom left, bottom right), 93 (left and right), 109 (top and middle left), 110, 112 (top and bottom), 113 (top and bottom), 114, 139 (left), 140, 141 (top); Chris Martin, pages 126 (left), 172, 173 (top and bottom); Geoff Maxted, page 159 (bottom);Ted Pearson, page 141 (bottom); public domain, pages 9, 10 (top and bottom), 15, 94, 138; Marvin Raaijmakers/Wikimedia Commons, page 16 (middle); Pava/Wikimedia Commons, page 139 (right); Phil Radoslovich, pages 145, 146 (top); Spanish Coches/Wikimedia Commons, page 104;Tasma3197/Wikimedia Commons, page 149; Lav Uly/Wikimedia Commons, page 142; Matthias v.d. Elbe/Wikimedia Commons, page 16 (left); Peter Vack, pages 52 (left and right), 159 (top).

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALFA ROMEO

CHAPTER 2 THE SIXTIES,THE MINI AND BIG HOPES FOR A SMALL ALFA

CHAPTER 3 A STAR IS BORN AND A LOST OPPORTUNITY

CHAPTER 4 THE ALFASUD GIARDINETTA

CHAPTER 5 SERIES 2 AND SERIES 3

CHAPTER 6 THE ALFASUD SPRINT COUPÉ

CHAPTER 7 THE ONE-OFFS, PROTOTYPES AND ODDITIES

CHAPTER 8 WHAT ALFA ADVERTISED AND WHAT THE PRESS SAID

CHAPTER 9 THE ALFASUD IN COMPETITION

CHAPTER 10 THE PROBLEMS, RUST, STRIKES, POLITICS AND CORRUPTION

CHAPTER 11 THE END OF ALFASUD, FUTURE MODELS AND FCA

APPENDIX I CHASSIS NUMBERS AND ENGINE CODES

APPENDIX II ALFASUD COLOUR CHARTS

Useful Links and Resources

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

More than one million Alfasuds sold in twelve years – 1,107,387 to be precise – making this Alfa Romeo branded car the bestselling model in the history of the Milanese car maker. Except it was not made in Milan and that would be the cause of many problems later.

The Alfasud was a brilliant design that deserves greater recognition, but as is often the way with the stories behind the Italian automobile industry nothing was quite straight- forward. The convoluted reasoning behind the project, and indeed the entire history of Alfa Romeo; is peppered with political intrigue, dodgy deals and even financial chaos, and often it seemed that the company itself was a triumph of optimism and bravura over mere practicalities. Many brands that had made a name for themselves since the dawn of motoring have suffered defeat, chosen a wrong turn technically, been bought by others or simply gone broke. Some, like Alfa Romeo, have survived by creating a reputation that was too good to die and have been absorbed into larger companies and that is the case with Alfa, today thriving as part of the Fiat Chrysler Automobiles multinational company, since January 2021 part of the Stellanti NV Group.

The Alfasud ready for production in 1971.

The Alfasud was a good idea at the time, created to fill a market for a small car that could undertake multiple roles, from family transport and suburban shopping to highway cruiser with performance to match. The political decisions that dictated where and how it was made may have made sense at the time, but proved in hindsight to be deeply flawed. The design, engineering and management team behind the concept were all the right people for the job, but even so political issues eventually overcame them too. Nevertheless, over those twelve years from 1971 to 1983, the little ’Sud made many friends and set a new standard for performance and handling that drew high praise from the press and similarly impressed anyone who drove one. It probably also had a direct influence on other manufacturers who had to bring new models to market to compete. Let down by problems not of its own making, it is a shame that so few survive today, but its DNA lives on in modern-day Alfa Romeo products that followed.

In the following chapters I will describe a brief history of how the company arrived at the brave decision to make the Alfasud, the design and engineering principles behind its conception and the ongoing improvements and additions to the line. Further chapters will deal with the Alfasud in competition, what the motoring press and road testers wrote about the various models, and the problems encountered along the way; all of which is inevitably tied to Italy’s parallel political history. I have also taken this opportunity to debunk and correct an oft-repeated myth about one of the Alfasud’s best-known faults.

I hope I have been fair in describing the good and bad points of this story and that all fans of the Alfasud and Alfa Romeo will find it an interesting read.

Acknowledgements

I have found that researching and writing is for much of the time a solitary, even selfish, way to pass the time, so it is with much gratitude that I acknowledge those who have helped me with this project. First is my ever-patient wife Karen, who not only encouraged me to start writing for various projects a few years ago, probably not realizing she would often not see me or even get an answer when I am lost in concentration at the keyboard, but she has also many times helped with proof-reading or suggesting a different way of saying something.

My thanks to Pedr Davis here in Australia and Peter Vack at VeloceToday.com who have both added comments about their experiences with Alfasuds and have also encouraged me in my writing over the last ten years. Of course, Alison Brown at The Crowood Press has been both patient and helpful bringing me up to speed with the minutiae of the publishing game. Frankie and Tim Guinness, Ted Pearson and Rex Greenslade have all been generous with their time and personal contributions to the story. Thanks also to Phil Radoslovich, who provided a couple of photos that added significantly to the chapter about competition, as did Ted.

My Italian skills are beginner level at best, but that did not stop a few people from Alfa’s home country helping my research. I owe a big thanks to Matteo Licata for steering me in the right direction about one particular myth of the Alfasud story that needed correcting, without which Chapter 10 would have been as inaccurate as many previously published reports, and Natascia Di Maggio at Giorgio Nada Editore for allowing me to quote some important text that supports these revelations. The ever-attentive staff at the Centro Documentazione Alfa Romeo at the Alfa Romeo Museum in Arese were an invaluable help, as were Gemma Perrone, Lorenzo Ardizio and Marco Fazio. Finally, thanks to Django our Golden Retriever for being patient when it is treat time and reminding me to go for a walk every day.

Chris Martin, Shellharbour, NSW, Australia

TIMELINE

1971 November

Launched at the Turin Motor Show

1972 April

Production starts, initially as a fourdoor saloon

1973 July

UK launch

1974 March

New two-door Ti model; five-speed gearbox, spoilers, improved seats, 68bhp, 0–60mph 12.9sec, 159km/h (99mph) top speed

1975

Giardinetta introduced

1977 May

Sprint launched with 1300Ti mechanical; five-speed gearbox for four-door 5M and Giardinetta

1977 August

1300Ti now 75bhp, 0–60mph 12.1sec; 1.3 now offered for four-door

1978 March

Sprint 1.5 added

1978 May

Series II; improved interior; 1.3Ti now 1351cc and 1.5Ti 1490cc 85bhp, 0–60mph 10.9sec, 163km/h (101mph) top speed

1979 February

Sprint Veloce; twin-carbs, 95bhp

1980 January

Series III; wraparound plastic bumpers; 1.5Ti Veloce twin-carbs, 95bhp, 172km/h (107mph)

1980 September

UK only TiS Special Edition

1981

Sprint Veloce Plus Edition

1981 February

Hatchback added for three-door

1982 June

Hatchback for five-door; Gold Cloverleaf twin-carb five-door added

1983

104bhp Ti Green Cloverleaf; UK only Sprint Speciale Edition

1984

Sprint restyled

1984 March

Alfasud saloon hatchback production ended; Sprint lost Alfasud name

1984 September

Sprint now had outboard front disc brakes, rear brake discs replaced by drums, tube rear axle replaced pressed type

1987

Sprint now had 1712cc 118bhp

1989

Sprint production ended

CHAPTER ONE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALFA ROMEO

CREATING THE BRAND

To understand the background to this story it is necessary to give a brief history of the Alfa Romeo brand leading up to the launch of the Alfasud in 1971. The Alfa Romeo brand today is synonymous with stylish cars with a sporting heritage, but it was not always that way. The company started with much more modest aims and has endured a complicated history of successes, takeovers and political interference.

In 1906, Frenchman Alexandre Darracq decided that there was a market in Italy for his small single-cylinder 8/10HP and 14HP twin-cylinder cars to be made with local labour and set up a local subsidiary named Società Automobili Italiana Darracq – S.A.I.D. – initially based in Naples, but soon moved to a new factory at Portello, a country area to the northwest of Milan. However, it became obvious within a couple of years that his cars were not suited to Italian roads and conditions, and sales were disappointing. As his cars were doing well enough in France, Darracq saw no reason to change his designs and was soon persuaded to sell out. The Italian managing director Ugo Stella and his partners bought and reorganized the company, recruiting Giuseppe Merosi to design a new range more suited to the local market. As the S.A.I.D. name still carried Darracq connotations the company was renamed on 24 June 1910 as Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili (which translates to English as Lombardy Car Making Company), but was better known by the acronym ALFA.

Giuseppe Merosi and a 24HP ALFA in 1910.

The first new model, the 4-cylinder 24HP, was introduced in 1910 and initially Merosi’s priority was to build a strong, reliable car. This was soon followed by a smaller, lighter version rated at 15HP and sales picked up. By the following year ALFA made its competition debut in the Targa Florio with Franchini and Ronzoni driving two shorter and lighter 24HP models specifically redesigned for the Sicilian challenge. That they did not finish the gruelling 444km (276-mile) race on muddy mountain roads did nothing to dissuade the company from continuing to pursue competition glory and results would soon follow with the stronger and more powerful 40/60HP model. This was to be the start of ALFA’s glorious competition history. Sales continued to improve until May 1915, when Italy joined the Allies in the fight against the Austro-Hungarian forces in World War I and the factory was turned over to more urgent military needs.

Although there were government contracts to pay for such work the company asked for more credit from the Banca Italiana di Sconto, which had held the last shares sold by the Darracq family. When the bank found itself holding the majority shareholding it asked Neapolitan industrialist Nicola Romeo to take control. Romeo had through other businesses already been benefiting from such military contracts and was actively looking to spread his investments as well as to acquire more manufacturing capacity, so as much by a coincidence of good timing as any forward planning Romeo took over as managing director. He owned several companies around Milan and the ALFA factory at Portello came under the control of Società Anonima Ing. Nicola Romeo and Co. in June 1918. Romeo also had a plant at Pomigliano d’Arco near Naples that produced aero engines.

Car production resumed in 1919, initially by assembling pre-war leftovers and in 1920 with a range of more up-todate models using the name Alfa Romeo, which now wore the badge of Alfa-Romeo Milano (the hyphen was not part of the company name and was only used on the badge and that in turn was dropped along with the reference to Milano in 1971). Merosi was forced to take legal action against the receivers over a salary dispute and after some unrest in the area, resulting in a factory lockout, production of his latest designs commenced in September 1920. By 1921, some fifty of the new G1 and 119 of the improved 20-30 ES chassis had been produced. The former featured a 6-cylinder 6330cc engine in a large chassis intended to wear large luxury coachwork, but it was not a great success; it seems most of these were sent to Australia. The more successful 20-30 ES scored some competition successes driven by Antonio Ascari, Giuseppe Campari, Enzo Ferrari and Ugo Sivocci.

By the end of the year the company was still in the red and to make matters worse the Banca Italiana di Sconto, which was the major shareholder, went into liquidation. The armaments company Ansaldo had in turn been the bank’s major shareholder and following the collapse of that company when peace returned to Europe the bank was left holding the debts. The liquidation of both Ansaldo and ALFA was managed by the government agency Consorzio per Sovvenzioni su Valori Industriali (Consortium for Subsidies on Industrial Values).

Merosi presented the new RL models in October 1921 in Milan and then at the London Motor Show, but due to further problems production did not get under way until 1923. This model featured a new 6-cylinder overhead valve engine of close to 3 litres and was offered as a luxury sedan or tourer, as well as several popular sporting variants until 1927. A smaller 4-cylinder RM model was also produced. At the same time, Merosi also developed the GPR (Grand Prix Romeo) as a pure racing machine and this would become retrospectively known as the P1.

Nicola Romeo, Enzo Ferrari and Giorgio Rimini at Monza in 1923.

Vittorio Jano and an Alfa Romeo P2.

The value of racing success was recognized by Nicola Romeo and in September 1923 he was recommended by one of the team’s drivers, Enzo Ferrari, to hire Vittorio Jano from Fiat to head a new competitions department. The first product resulting from this was the P2 of 1924, which was immediately successful and won the inaugural World Manufacturers’ Championship for Alfa Romeo in 1925, by which time Nicola Romeo had become president of the company. This was the first of a long run of Jano designs, which was followed by the 6C1500, a lighter 6-cylinder powered car that would form the basis of a series of sporting cars. The management decided that the future of Alfa Romeo production would be better served by concentrating on such designs rather than the bigger and thirstier RL series. This led to Merosi resigning in 1926. Although Alfa Romeo still had other products such as aero engines in its portfolio a depression was on the way and Nicola Romeo retired at the end of the decade.

With Enzo Ferrari heading up Scuderia Ferrari, Alfa’s official race team, racing success continued into the 1930s with the 8C-2300, known as the Monza, and the Type B Grand Prix car, also known as the P3, as well as several variations on Jano’s supercharged 6- and 8-cylinder powered sports cars. However, the depression had severely affected the Italian economy and the Banco Italiana di Sconto, still a major shareholder, was in trouble.

In 1933, Mussolini’s government instructed the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI) to take control, a decision probably driven by the fact that Alfa Romeo aero engines and other contributions were vital to Mussolini’s drive to increase the nation’s armaments and to avoid further unemployment as much as any wish to keep the brand in racing for national pride. Indeed, although such success on track did bring a certain prestige to a struggling Italy, by this time car production and sales were declining rapidly. Ugo Gobbato was appointed managing director. By now, the P3 was beginning to lose out to the new threat from the mighty German Mercedes and Auto-Union silver machines, although the Scuderia Ferrari managed still to pick up a few good results and the final iteration with the motor bored out to 3.8 litres was still capable of winning in 1935.

With a view to increasing sales of road-going cars Jano was tasked with designing a new 6-cylinder 2300, itself derived from the earlier 6s, which would power a new chassis that, combined with the increase in torque, could carry heavier coachwork and be built in larger numbers at a much lower price than the expensive 8s. Sales did indeed improve, with the various 6C models selling in their thousands, while shorter wheelbase GT chassis clothed in lighter bodies kept the spirit of sporting Alfas alive.

Within a few years, the inevitability of war in Europe meant the government’s priorities dictated that Alfa once again try to regain some glory on the race circuits, while gearing up for increased production of aero engines ensured enough income from Mussolini’s war chest. To this end, several designs for larger capacity engines of straight-8,V12 and even V16 were tried on the track with limited success, Ferrari even running the famous twin-engined Bimotore, which, while potentially fast, lost any advantage thus gained by needing more frequent tyre changes during a race. The failure of the V12-engined 12C model in 1936 led to Jano’s resignation and he subsequently joined rival Lancia. There were better results in prestigious sports car races such as a one, two, three in the Mille Miglia of 1936, with the 8C-2900A using a new 3-litre version of the old P3 motor and more results followed with the 6-cylinder road cars scoring first and second at the following year’s Mille Miglia.

The big 8s also continued to be made, but this was probably more to do with keeping up appearances and garnering prestige than adding any significant earnings to the coffers; in fact, only twenty of the sporting 8C-2900B Corto chassis and ten of the longer wheelbase 8C-2900B Lungo were built between 1937 and 1939. Indeed, during the second half of the 1930s Alfa was producing more industrial and commercial vehicles than private cars.

At the same time, while the big racers failed to deliver results on track, a smaller, lighter model was developed for the new Voiturette class of races intended as a sideshow warm-up race before the main event Grands Prix. The rules for these cars required supercharged 1.5-litre engines and Alfa Romeo achieved this by using one half of the big V16 to power the independently suspended chassis that became the 158. This car showed promise and became known as the Alfetta (little Alfa), but as war approached it would have to wait a few more years to achieve its potential.

The war years at least ensured that the aero-engine production brought much needed income into the company accounts, but the same conflict also meant that Alfa’s manufacturing bases at both Portello and Pomigliano d’Arco were frequent targets for Allied forces bombing raids. Milan, as a major industrial centre, was an obvious target and 60 per cent of the factory and much of the machinery and tooling were destroyed by heavy bombing in 1943 and again in a final raid in October the following year. The southern factory near Naples suffered a similar fate in May 1943. After the war this factory was used initially to build some buses, trams and trucks, but from the late 1940s was returned to aircraft production, including some projects in collaboration with Fiat. We will return to the Pomigliano d’Arco site later.

POST-WAR REBIRTH

The Portello plant was so badly damaged that it had very limited manufacturing capability and was used initially to make small electrical cooking appliances and other domestic products needed to rebuild the war-ravaged country. Some of the 8,000 employees were put to work rebuilding the plant so that car production could resume in 1946. The 6C 2500 model using pre-war mechanical underpinnings with a new streamlined body was the first to wear what would become the traditional front grille combining the central shield with horizontal air intakes at either side, a styling motif that would continue to this day. Alfa could sell these as fast as the company could turn them out in car-hungry post-war Italy, but to truly increase production it was realized that an all-new concept was needed. The factory had been expanded with a corresponding growth of the workforce for the wartime needs and now everything was in place to increase car production.

Jano’s replacement, Dr Orazio Satta Puliga, known as simply Satta, who was only thirty-seven years old in 1949, came up with the new 1900, which was first shown to the public in Turin in May 1950. The 1900 was designed for the new production-line methods now being installed at Portello. It featured a monocoque body and chassis unit, which, while lightweight, would have enough interior space to be a genuine four-seater. The engine was a 4-cylinder retaining the traditional Alfa theme of hemispherical combustion chambers and twin overhead camshafts with an alloy head on a cast-iron block. Initially producing 90bhp, enough to give the new car a sporting urge, this engine was soon upgraded with more power and as production increased, so did sales.

The new car, while having a plainer look than the earlier models, with 90bhp and agile handling was still sporting enough to uphold the company’s reputation, selling as fast as the factory could turn it out. It was also the first Alfa made to left-hand-drive specification, an important consideration when aiming for lucrative American sales.

An increase in power to 100bhp for the TI followed and to meet the demand for an even more sporty Alfa the wheelbase was reduced for an open-top version bodied by Pininfarina and a coupé clothed by Touring. Although only a small share of the total production, the success of these more expensive and glamorous models encouraged Alfa to consider that the successor of the 1900 should also include this market sector again. The ‘Italian Economic Miracle’ of the 1950s meant that the demand was there, but the company also had to consider export markets, as well as the taxation based on engine size for Italian car buyers.

Motor racing resumed and in 1950 the six European Grands Prix counted towards the new World Championship for Drivers, which was won by Giuseppe Farina, who shared an Alfa Romeo clean sweep with Juan Manuel Fangio in the revived 158. Curiously, the Indianapolis 500 also counted towards the points tally, but was not run to the Formula One rules and none of the title contenders bothered going. Updated for 1951 as the 159, it was again successful with wins for Farina and Fangio. The latter would be champion that year and then once again Alfa withdrew from the Grand Prix circus, apparently to concentrate resources on increasing production of road cars.

Launched in 1954, the Tipo 750 Giulietta was smaller and lighter than the 1900 and the engine size was reduced to 1300. This power unit with an alloy cylinder block and the by now typical twin overhead camshaft head was designed with the option of an increase in capacity and would form the base of many more powerful versions to follow. The Giulietta was initially shown at the 1954 Turin Motor Show as the Sprint 2+2 coupé with bodywork designed by Franco Scaglione and built at the Bertone plant near Turin. The fourdoor saloon Berlina would follow in 1955, as well as an open two-seater Spider by Pininfarina and later a more powerful Berlina TI. A redesign in 1959 saw minor changes and the entire range was now given the Tipo 101 designation. Power boosts were achieved through this range by raising compression and improving carburetion. There was another restyling to refresh the looks in 1961.

Other landmark models, including the extravagant Disco Volante experimental sports cars built by Touring, featured streamlined bodywork that was refined in a wind tunnel and five different examples were made in 1952–3. These were followed by three even wilder BAT show cars designed by Scaglione at Bertone and their futuristic shapes certainly made headlines at the time. Based on the 1900 chassis and intended as studies in aerodynamic efficiency, they are today regarded as styling classics but were never intended for production and had no further influence on the next generation of Alfas.

THE ITALIAN ECONOMIC MIRACLE

From the post-war devastation of 1945 until the period of civil unrest in the late 1960s Italy underwent a sustained economic growth that has become retrospectively known as the ‘economic miracle’. After the defeat of Hitler and Mussolini the British and American Allies inherited a responsibility to help rebuild Europe and in so doing limit the spread of Stalinist communism that had already closed much of the northern and eastern parts of the continent behind the Iron Curtain.

Italy had, before the war, been a relatively poor, mostly rural, country with a reliance on agriculture rather than big industry, although Mussolini’s ambition for military might had seen significant investment in companies like Alfa Romeo. The American government formulated a European Recovery Program to aid rebuilding Western Europe and adopted what became known as the Marshall Plan. From 3 April 1948, the United States sent $12 billion over the next four years to aid recovery. The aims were to rebuild war-damaged regions and infrastructure and to create employment. In order to encourage growth, there were moves to remove trade restrictions across borders. Of course, it was also hoped that by buying international alliances the USA could prevent the spread of communism to the West.

The Communist Party of Italy had been outlawed under the Fascist regime, going underground to help with the resistance during the war. Reformed as the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI) in 1943, by 1947 it was the largest communist party in western Europe, with over two million supporters. This, along with Italy’s position in southern Europe close to the eastern regions now under Soviet control, made for a pressing case to restore the economy as soon as possible. The funds were awarded on a per capita basis and Italy received $1.5 billion. Later, demand for manufactured products for the Korean War, followed by Italy joining the European Common Market, increased investment and employment in industry and contributed to a sustained economic growth that lasted until the social unrest and widespread strikes of the summer of 1969.

The major part of the industrial growth was centred around the northern cities, resulting in mass migration of workers from the mainly rural south. This in turn created expansion of these cities, which needed greater transport infrastructure and further investment in improved roads and railways, as well as more housing for the workers. Italy also became known for fashionable clothes and shoes and the manufacture of typewriters and refrigerators along with other consumer goods, which all helped to earn export currencies. State banks were making finance easily obtainable and taxes were low, again increasing employment and consumer spending. In the ‘boom’ years from 1958 to 1964, industrial growth rates exceeded 8 per cent per year.

Not everything was rosy though; the outskirts of these cities saw a massive expansion of low-cost apartments and cheap housing that would contribute to congestion and, later on, the inevitable urban decay. The need for increased mobility added to sales of more cars and the affordable small Fiats and Vespa scooters saw record sales, putting many more Italians on the already congested roads. Normal human aspirations being what they are, in time many of these same consumers would move up to an Alfa Romeo, with luxury brands like Ferrari, Lamborghini and Maserati also seeing increased sales through the 1960s. The economic growth did, however, benefit the country as a whole and saw improved standards of living for most Italians.

THE FIRST ATTEMPT AT A SMALL CAR

Alfa Romeo mechanical engineer Giuseppe Busso had briefly experimented with a radical new design in 1952, codename Project 13-61, incorporating a transverse-mounted frontdrive engine and transmission, but this was shelved due to lack of finance to develop it further as all resources were concentrated on the coming Giulietta. If the company had persevered with the original concept this would have preceded the Mini as the first of its kind.

Austrian-born Rudolf Hruska had been a consultant to Finmeccanica, the division of IRI that controlled various state-owned mechanical and engineering businesses including Alfa Romeo, of which Hruska was to become Technical Manager. Hruska told Busso that Finmeccanica was interested in developing a new small car, so Busso dusted off his earlier design studies for the Alfa board’s approval. Work continued and by 1957 a front-wheel-drive layout was confirmed, although proposals for air-cooled and flat-4 ‘boxer’ engines were shelved. The first drawings were completed the next year and by now a 900cc version of the existing 4-cylinder engine was confirmed. This was later instructed by management to be reduced to 850cc, but finally settled on 896cc. Production was scheduled for 1961.

Alfa Romeo Tipo 103.

Rudolf Hruska had left the company in 1959 after disagreements with then President Balduccio Bardocci (Hruska later claimed he was sacked) and had gone to work for Simca and Fiat, but the project continued development into the planned new Tipo 103 model. The final design featured a boxy four-door saloon looking vaguely like a scaled-down version of the Berlina, but with front-wheel drive, coil spring suspension and disc brakes all round. The engine now had a bore of 66mm and a stroke of 66.5mm; at 896cc it was the smallest ever iteration of the twin-cam four produced. By 1961, the prototype Tipo 103 was running with three examples of the engine built, but then the decision was made to shelve it again to concentrate resources, this time on the new Giulia expected the following year.

This decision was also influenced by Alfa’s new relationship with French manufacturer Renault (another stateowned company), which would handle Alfa Romeo distribution in France. At the same time, the Renault Dauphine and its upmarket variant named Ondine were built under licence at Portello from 1959 to 1964. The compact rear-engined Dauphine Alfa Romeo sold 70,000 units in that period and this also saved the cost of tooling up for another small car model that would have been a direct competitor. This was accompanied by another 40,000 examples of the frontwheel-drive Renault R4 hatchback between 1963 and 1964. Coincidentally, or maybe not, the Dauphine’s successor, the Renault R8, featured very similar boxy styling to the stillborn Tipo 103.

Another new model was introduced in 1958, the Tipo 102. With a 2-litre 4-cylinder engine, the 2000 series was also offered in Berlina, Sprint and Spider guise. This was another attempt at selling to a more luxurious and higher-priced market sector, but with total sales of all models falling just short of 7,000 it was not a great success.

1960S – ON THE RIGHT TRACK

The eventual replacement for the Giulietta, the Giulia sedan, was introduced in 1962, but the existing Giulietta Sprint and Spider versions, which now received the new enlarged 1600cc engine, were renamed as part of the Giulia range too, to be replaced by all-new Giulia designs in 1965. There had also been an Estate model Giulietta, which was also produced by subcontractors, but these were only made in small numbers. By the end of the run, 177,690 Giuliettas had been sold – sales which indicated that at last Alfa Romeo was on the right track.

The new Giulia, Tipo 105, was available with the base 1300 engine and four-speed gearbox, but the majority were fitted with the 1600 and five-speed combination, which gave impressive performance in the small four-door. This continued in production until 1974 with a wide range of specifications, the 1300 and 1600 both being offered as Super or TI in various states of tune. However, it is probably the more obviously sporting variants of the Tipo 105 that people first think of whenever Alfa Romeo is mentioned and these went on to be produced in large numbers, sold around the world and still regularly seen on the roads today. The 105 series Giulia Sprint GT was current from 1963 to 1976 and available at different times, with many variations on the basic theme. The body was designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro for Bertone and mechanical specifications included 1300, 1600, 1750 and 2000 engines, although common to all were the five-speed transmission and four-wheel disc brakes. All had twin carburettors except American market GTVs, which had mechanical fuel injection. There were close to 1,000 of the convertible GTCs built by Touring, while Zagato built 1,519 examples of the 1300 and the 1600 Junior Z coupé. The much prized GTA competition models featured aluminium panels and were available in various configurations from 1965 to 1975, with many customers having them further modified by the competition department, Autodelta.

The equally popular Spider, based on the 105 platform and designed and built by Pininfarina, had an even longer run, going through four distinct series until the last left the line in 1994. Meanwhile, the 2000 was replaced in 1962 by the 2600 (Tipo 106), featuring a 6-cylinder engine giving between 130 and 145bhp according to carburetion and again available as the Berlina saloon, a Sprint coupé by Bertone and a Touring-bodied Spider convertible. As usual, there were some special-bodied versions; the Sprint Zagato saw 105 examples built between 1965 and 1967 and boasted 165bhp equipped with triple Solex carburettors.