Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

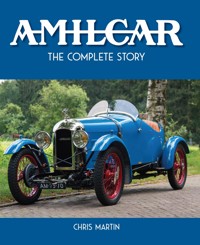

Amilcar – The Complete Story is a journey through Amilcar's history, starting with the rebuilding of the French automobile industry out of the ashes of World War I and the opportunistic meeting of the four key people who started the company. The roller-coaster ride continues through the Roaring Twenties and hardships of the Depression years, to the last struggles to keep the Amilcar name alive.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Timeline

Chapter 1

France 1920

Chapter 2

1921 – The First Amilcars

Chapter 3

1922 – Competition Successes and the New Models

Chapter 4

1923 – New Models, More Racing

Chapter 5

1924–25 – Growth, a New Factory and Tragedy

Chapter 6

1926–27 – More Success But at a Cost

Chapter 7

The 6-Cylinder Cars

Chapter 8

1927–30 – The C8 and Trouble Ahead

Chapter 9

1931–34 – The M2, M3 and the New 5CV

Chapter 10

Another Move – The Pégase

Chapter 11

Hotchkiss and the Compound – The End of Amilcar

Chapter 12

The Amilcar Agents Abroad

Chapter 13

Salmson and the Other Rivals

Chapter 14

The Racing Drivers

Chapter 15

What the Press, and Others, Said

Chapter 16

Amilcar Trivia

Appendix I

Technical Specifications

Appendix II

Competition Results

Appendix III

The Original Parts Suppliers

Bibliography, References, Sources and Notes

Useful Contacts

Index

INTRODUCTION

As I had always been interested in old cars, racing and most things French, it was probably inevitable I would become interested in Amilcars; consequently, I am currently running a restored 1925 CS and working on rebuilding an early C4. Having the chance to write the history of these cars has also been an interesting journey, researching the ups and downs, the various models and where they are today.

First, I should explain the problems with researching a subject that started over 100 years ago and for which there are no primary sources – first-hand witnesses – still alive.Yes, today we are fortunate to have the resources of the internet available to all, and true, there is much information there, but much of it is not properly verified. It is all too easy to publish something online that is just a repetition of rumour, hearsay and incorrect theories, such that if a statement is repeated often enough it becomes accepted as fact. Even so, there are some resources that are indeed well researched and valuable for checking details. I have included an appendix listing all of the sources I have referred to, as there has been a lot already written by respected writers, historians and experts in the field, but even those writers do not always agree. Where there may be a discrepancy in the stated facts, I have added reference notes that may offer alternate explanations.

This book aims to cover the Amilcar story from the start in 1921 through to the demise of the marque in 1939. I start with a brief explanation of the situation in France and the French automobile industry after World War I to give some background as to how and why the Amilcar was born.

The following chapters deal with the history in a chronological order where possible, detailing the models and their place in the market as well as their results in competition, although some specifics will be dealt with in their own chapters. Each model is illustrated by both period photos and a story or two about survivors that have been restored and are still giving their lucky owners enjoyment on the road today.

After the 6-cylinder racers the competition department was wound up and Amilcar went through several changes of management, trying to find their place in the medium car market but with limited success; the relevant chapters cover this period with more detail regarding the financial struggles and changes of management and direction until the end in 1939.

Later chapters cover the rival brands, the Amilcar in international markets, period road tests and press reports, related ephemera and a few odd Amilcar tales. In each chapter I have also added some occasional historical notes not specifically about Amilcar but relevant to the times.These are intended to help paint a picture of cultural and historical events that would have had an influence on the city of Paris, the rest of France and its neighbouring countries through the inter-war period.

Several of the Amilcars illustrated in these pages are in Australia. I make no apology for this and it is not just because I now live ‘down under’; the Amilcar was always a popular car here, selling in large numbers especially in the southern states, and there is still a healthy interest among the many owners who keep about 100 of these delights on the road. I have also included several cars from the Netherlands, where there is a particularly healthy Amilcar community, as well as contributions from British, French and German Amilcar owners.

After the chapters covering the full story in chronological order there are appendices with competition results, technical specifications, the suppliers of outsourced parts, and information about clubs, and a bibliography.

Were they really just a ‘Poor Man’s Bugatti’ as the old cliché says, or do Amilcars deserve to be recognised initially as an affordable sporting car followed by a significant racing machine and later making cars of some merit in what were difficult times? Amilcar started by making a cheap utilitarian small car that could take advantage of the new cyclecar regulations, with no initial ideas of sporting use, while Bugatti were already having competition success with the Brescia Type 22/23. When Morel and others took to the tracks Amilcars were not competing with the Bugatti Type 35, which was probably the most successful Grand Prix car of all time. By the time Amilcar made a real racing car, the C6, it cost more than the Bugatti Type 37, which was the nearest Bugatti ever got to an affordable sports car for the amateur driver.

In the 1930s Bugatti’s glamorous models were made for the exclusive and expensive end of the market, while the Amilcars of the same period were aimed at the middle classes who by 1934 were buying the Citroën Traction in their thousands. Read on and unravel the ups and downs of the Amilcar story. Amilcar Un Jour, Amilcar Toujours!

TIMELINE

1919 André Morel meets Edmond Moyet at the Excelsior restaurant. Émile Akar and Joseph Lamy agree to finance the new car.

1920 New premises at 34, Rue du Chemin–Vert; work begins on new car, for now called the Borie Cyclecar.

1921 19 July: The name Amilcar is registered.

29 September: Articles of the company Société Nouvelle pour l’Automobile (SNPA) published.

6 October: Amilcar CC launched at the Paris Salon.

23 October: Morel 1st in class for the flying kilometre at an average speed of over 90km/h.

Marcel Sée joins as technical director.

1922 19 February: Victory for Munch in the Forest of Marly near Versailles leads to setting up an official Competition Department.

27–29 May: Morel wins the Bol d’Or.

2 July: Morel sets flying kilometre record for 1100cc class at 120km/h.

17 September: Morel crowned 1922 Speed Champion of France and Amilcar win Constructors Champion of France in the 1100cc class.

CV and C4 shown at the Paris Salon. 10CV E Type announced for 1923.

1923 The CS and GCS launched at the Paris Salon and patent applied for front wheel braking system.

1924 16 May: Patent issued for front wheel braking system. Competition Department expanded and renamed Racing Department.

Amilcar moved to a new factory in Saint-Denis.

CGS3 added to the range.

2 October: Paris Salon – Amilcar launch the 7CV G Type and the 10CV J Type.

1925 Morel wins the Bol d’Or again.

Marius Mestivier killed at Le Mans.

Racing debut for the 6-cylinder CO.

Amilcar buys Margyl coachworks.

Morel sets flying kilometre record for 1100cc class at 147.42km/h.

Paris Salon – The CGSs replaces the CGS.

1926 25 September: Martin, Duray, Morel finish 1,2,3 at Brooklands JCC 200 Miles.

At the Paris Salon, the first showing of the C6 to be available for the next year.

1927 15 January: Marcel Lefebrve-Despeaux wins the Monte Carlo Rally in an Amilcar G Type.

New ‘Offset’ version of the CO racer.

SNPA in liquidation. The new company Société Anonyme Française d’Automobile (SAFA) takes over with Marcel Sée and Albert Neubauer in charge. Akar and Lamy leave.

L Type replaces the G Type at the Paris Salon.

1928 Larger 1270cc version of the CO engine developed for the 1500cc class.

Amilcar announces deal with Durant Motors to sell Amilcars in the USA.

Eight-cylinder C8 chassis and M Type introduced at the Paris Salon.

Racing Department closed down.

1929 André Morel leaves the company.

Last official outing for any works Amilcar racers.

Jules Moriceau enters the Indianapolis 500.

Wall Street Crash ends the Amilcar Durant alliance.

M2 replaces the M Type and C8 and CS8 announced at the Paris Salon.

Clément Auguste Martin buys remaining team racing cars.

1931 Paris Salon showed only the M3 and CS8 models.

1932 5CV C Type introduced alongside the M3 at the Salon.

1933 Administrators André Briès and Marcel Sée set up new holding company, Société Financière pour l’Automobile, (SOFIA) to raise finance.

CS8 dropped, C Type updated as the C3. New M4 introduced.

Edmond Moyet leaves Amilcar.

1934 C5 replaces the C3 and aerodynamic updates offered for the M3 and M4.

Prototype Pégase shown at the October Paris Salon.

1935 Pégase goes on sale with ten body styles offered.

1936 Pégase range reduced to just four models. Hotchkiss buys into Amilcar.

1937 Hotchkiss takes over Amilcar. Pégase production ends. Amilcar Compound B38 shown at the Paris Salon in October.

1938 Production of the Compound started in April 1938 with new 1185cc engine.

1939 Compound B67 announced with new 1349cc engine.

1940–1942 Sales of Amilcars stop when Germany occupies Paris. A few last Compound chassis were built as vans and ambulances.

CHAPTER 1

FRANCE 1920

To fully understand how and why the Amilcar marque came to be, and why the new model was the right idea at the right time, it is useful to summarise the historical context that helps to set the scene at the time of the creation of these wonderful cars. Several circumstances contributed to the birth of the Amilcar, the coincidental timing of which was critical.

There had been a phenomenon known as the ‘Cyclecar’ around for a few years, but it took hold in France in the early 1920s. There was already a well-established car manufacturing industry in France; it could be said this country was probably one of the first to embrace the new-fangled automobile in any quantity, although Britain, Germany and America were not far behind. To give some background to this story, what follows is a brief description of the economic, political, industrial and sociological conditions in France at the time followed by a brief overview of the local motor industry, particularly the people and companies that were to play a part in the birth of the Amilcar.

FRANCE AFTER THE GREAT WAR

Following the 1914–18 war France found itself in a dire economic state. Despite the intentions of the Treaty of Versailles to ensure Germany should pay for all restoration of the damaged infrastructure, industry and agricultural land, France received nothing from a country that was in an even worse financial state. Added to the problems of rebuilding factories, mines and farms, there was a chronic shortage of manpower. Over 1.5 million French soldiers were killed and many more left with disabilities. This alone meant there was a significant reduction in the number of workers who would otherwise have been employed in the French car industry. Prior to the war, immigration was not regulated in any way to be advantageous to either industry or the local population and workers were needed in both the growing industries as well as France’s widespread agricultural interests. There was a desire by 1920 to enact some laws to control immigration. This was so that skilled labour could be encouraged while the flow of unskilled people was restricted – particularly those from the colonies. During the war years, many of the latter had been found unsuitable for general labour. There was also a desire to prevent cheap labour from driving down wages for the indigenous population. In the early 1920s, some 20,000 Belgians were already employed, mostly in mining and agriculture, and much of the shortfall of skilled workers under the new regulations would be taken up by immigrants from Czechoslovakia, Italy and Poland. These were followed by Portuguese and Spanish immigrants for less skilled work. By 1924, over a million foreign workers had come to France and this influx of imported labour was an important component of the economic growth of France in the decade following the war.

Politically, the mood of the country remained conservative: the peasants who had continued to farm the land were profiting well enough from their markets and what socialist attempts there were to unionise the labour force were fruitless; France had been taking notice of the recent Bolshevik revolution in Russia and wanted no such thoughts to influence its workers. Widespread strikes by the unions in May 1920 were crushed by the government supported by the majority. In 1919 Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau had implemented the eight-hour working day for most trades (excluding farmers) and working conditions had improved across the board. Clemenceau had been Prime Minister throughout the war and was a prominent author of the Treaty of Versailles. He had wanted Germany to be punished, but other influences were at work to bring peace to Europe and even to help Germany get back on its feet. All of this weakened Clemenceau’s position and, after his defeat in the presidential election in January 1920 by Paul Deschanel, he took no further part in politics. He was replaced as Prime Minister by Alexandre Millerand, who in turn became President in September that year after the resignation of Deschanel, but the general political climate remained largely conservative.

Increased taxes on consumers had been a worrying burden since the war – necessary in order to fund the government’s policies – but output in both manufacturing industry and agriculture was still considerably lower than it had been prior to 1914. Exports in 1920 were indeed much increased over the previous year, but any benefits were negated by the falling value of the French franc against other currencies, which combined with higher taxes to cause a steep rise in the cost of living.

The necessary reforms resulting in the Finance Law of 30 July 1920 had been planned as far back as 1919, but other parliamentary business held up the required ratification. Through that period Louis Lucien Klotz was the Finance Minister from 1917 through the war years until January 1920, when he was replaced by Frédéric François-Marsal, so it is not clear who was responsible for drawing up the final draft. It is often thereafter referred to as the ‘Le Trocquer Law’ after Yves Le Trocquer, the Minister of Public Works with responsibilities for transport policies who pushed for an incentive to give a boost to the car industry and at the same time encouraged more people to gain motorised mobility. It may have seemed an odd move to be going against the pattern of increased taxes of the previous two years, but it was a priority of the government to help reinstate the once prosperous motor industry at least at the cheaper end of the market. Certainly, there was also a keen demand among the French population to become mobile and join the motoring classes.

WHAT IS A CYCLECAR?

In the early years of the automobile industry there was no standard specification, and most of the engineers responsible were still finding their way with various choices of large-capacity engines capable of pulling the luxurious coach-built limousines and tourers down to the most basic single-cylinder runabouts. Petrol power had by no means a monopoly, with steam and electric cars also improving as viable alternatives.

The trend for smaller, affordable cars created what were to become ‘cyclecars’ in most of the bigger markets, Britain, France, Germany and the USA from around 1910. These were usually very basic lightweight cars or tricycles with single- or twin-cylinder motorcycle engines and, on 14 December 1912, the Federation Internationale des Clubs Moto Cycliste announced an international classification of cyclecars that was adopted by Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States. This defined a cyclecar as a single- or two-seater weighing not more than 350kg (772lb) with an engine capacity not exceeding 1100cc. Some were no more than a light frame with three or four wheels and a motorcycle engine, often a single- or twin-cylinder unit, which had to work hard to move anything close to the maximum weight. Extreme cases might include the Smith Flyer (later sold as the Briggs & Stratton Flyer), the Dudly Bug and the Scripps-Booth Rocket in the USA and in the UK the Morgan three-wheelers, the AC Sociable and the GN were moderately successful. Others came and went in Europe, particularly in Germany and Italy, but France was the most prolific in terms of cyclecar manufacturers. Many of these came under a loose definition of what was known as a cyclecar, but it was the new ‘Le Trocquer Law’ that gave the French car industry a clear incentive to build small cars that complied to a workable set of rules.

One peculiarity of the laws governing the registration and tax liability of motor vehicles in early twentieth-century France was that this all fell under the responsibility of the ‘Service des Mines’ who applied their own formulae for calculating the taxable horsepower, or the CV figure. This probably came about as the mining industry had, since the nineteenth century, some expertise and familiarity with powered machinery. Although in modern times France has streamlined its bureaucracy and government departments, a car registration plate is still often referred to as a ‘plaque minéralogique’.

The new tax regulations provided for a reduced tax of 100 francs per year for cyclecars, the same rate as for motorcycles at the time. An explosion of small manufacturers resulted, but most of these were nothing more than assemblers of bought-in components; axles, engines and gearboxes all sourced from proprietary suppliers of varying quality and efficiency. Most of these small workshops were situated in the industrial area stretching from Boulogne in the west of Paris to Saint-Denis in the north, encompassing Puteaux, Levallois-Perret, Courbevoie and Asnières-sur-Seine, all place names that will be familiar to anyone with an interest in vintage French cars.

The better-equipped manufacturers such as Mathis, Peugeot and Salmson, however, were able to build complete cars using parts made in house and, from the start, Amilcar also fell into this latter category.

In 1920 there were 814 cyclecars registered in France and the demand quickly grew such that by 1924 there were 29,542 happy cyclecaristes paying the reduced rate, but their days were soon to be numbered. An amendment to the finance law in April 1924 raised the tax to 120 francs and at the same time lowered the voiturette rate for cars with engines of less than 1500cc to 180 francs. There was already a reduced demand for these basic machines and the lower cyclecar tax was abolished altogether in 1925.

The original definition of a cyclecar in 1920 that limited the weight to 350kg was for the basic rolling chassis with minimal bodywork and excluded accessories like lights, spare wheel and starter, all of which of course were available from the dealer to be installed after the car was registered. A contemporary report said:

The French have always been rebellious and worked to subvert the law. So, the buyer received two invoices, one for the car, stripped of lighting, roof and spare wheel, the other for whatever accessories he had ordered.

If the cars had been delivered fully equipped, they could never have met the 350kg limit. Although Amilcars and many others continued to be known as cyclecars for many years after, they only qualified under the regulations until 1923, by which time they were classified as voiturettes due to the increased weight of the improved models designed to appeal to a wider market.

THE FRENCH MOTOR INDUSTRY IN 1920

It would be useful here to understand the main players of the French car industry following the 1914–18 war; for various reasons, major changes were about to take place. Many of the established brands would continue making cars based on the earlier veteran models that had served them well enough through the first fifteen or twenty years of the pioneering days of motoring, but they would soon be pushed aside by new names that had benefited from the war and started afresh with more modern ideas. While the automobile had been the preserve of the wealthy few with a taste for adventure back in the pre-war days, it was soon to become an affordable and reliable alternative to the horses or bicycles the ordinary working man had been used to. New thinking was needed: where previously such machines had been handmade by skilled engineers, production line mass production, as had been demonstrated by Ford in America, would be needed to meet the emerging market.

Once great names like Delaunay Belleville lost their way and diverted into making trucks before fading away; Berliet likewise suffered problems in the 1920s and did better with their commercials. Many other established names like the once mighty De Dion Bouton struggled through the 1920s, the last passenger car being produced in 1932, although the name survived with a few commercials until 1950. Darracq was absorbed by Talbot and the name was lost after 1922; Unic lasted until 1938, by then best known for their taxis, although again a few commercials carried the name until a takeover by Simca in 1953. Léon Bollée was taken over by Morris in 1924 and Clément-Bayard was bought out by Citroën in 1922, as was Mors in 1925, in both cases to increase factory capacity. Chenard & Walcker faded away during the 1930s and was taken over by the Chausson company and then Peugeot in the late 1940s. Mathis stumbled on until a merger with Ford in 1934 to form the Matford brand, which itself did not survive the 1939–45 war.

Ford had already had a presence in the French market since before the war; French agent Henri Depasse had set up a venture, with Model Ts being assembled at a factory at Bordeaux. This was taken over by the newly set up Ford SAF and manufacture increased when they moved to a larger factory at Asnières-sur-Seine in 1925. Because of the heavy taxation on the original 2.9-litre engine, Ford introduced a sleeved-down 2-litre version for the European markets. The simplicity of manufacture and subsequent sales success had a lasting influence on the French automobile industry.

Hotchkiss had long been established as an armaments manufacturer since 1867 and had already made a name for themselves with some luxury cars since 1903. Post-war investment in new factories in France and Britain and the new AM series launched in 1923 would continue the name into the 1930s when they too struggled to sell new models, but the name continued until 1970, making trucks and military vehicles. Hotchkiss will reappear in the Amilcar story later.

Many of these manufacturers had profited well from military contracts during World War I but were not prepared for the new market demands of the 1920s. Two exceptions were of course Peugeot and Renault, who had been among the first established motor companies with a sound pedigree in competition since the early years. Peugeot’s small cars: the Ettore Bugatti-designed Bébé launched in 1912 and the later Type 161 Quadrilette and the 10hp Type 163 of the 1920s establishing the name as a popular brand. Likewise, Renault, who continued after the war with a strong line of medium to large cars, although through this period they did not have a share of the now popular market for small cars of the 5hp to 7hp range.

Le Zèbre

One more of the French car manufacturers that was at a loose end after the war was the small Le Zèbre company.

Le Zèbre advertisement.

Le Zèbre Torpédo Type A 1913.

Jules Salomon began his career as a young engineer working for Georges Richard, one of the many motoring pioneers of the late nineteenth century who had graduated from making bicycles. Richard sold out to Brasier and went on to start Unic in 1905 with Jacques Bizet (son of the famous composer Georges). In 1909, Salomon teamed up with Bizet to start up their own company, which they called Le Zèbre. One story suggests this was a nickname for a fellow employee at Unic, the office boy who was known to run fast on errands, which may seem a fairly tenuous connection, but another theory was that it was fashionable at the time to name car marques after animals: Licorne (Unicorn); Lion-Peugeot; Ours (Bear); Sphinx and so on, but whatever the origins the name stuck. Another story has it that it was the name of a dray horse used to haul goods at the Unic factory. The first cars were made at the Unic factory in Puteaux before the Le Zèbre company was formally set up as a separate identity. With capital from the banker Henri de Rothschild, who also had a stake in Unic, and Bizet in charge of the finances and presumably the management of the business, the company was initially registered as Bizet Constructions, and Jules Salomon was the engineering brains responsible for the design of the Type A, launched in 1909. Featuring a 630cc single-cylinder engine and two-speed gearbox, it was something of a bargain with a price of 3,000 francs, well below the average cost of the competition. These had been immediately well received, making Le Zèbre a popular brand.

The leading motoring journalist of the time, Louis Baudry de Saunier, who contributed to the weekly magazine L’Illustration and was the publisher of Omnia, a monthly motoring magazine, was impressed and often wrote favourable reports extolling the virtues of Le Zèbre cars, although it has been suggested that he may have also had a financial interest. In 1911 the company was registered as Société Anonyme Le Zèbre. The business soon attracted investment from two prominent businessmen, Emile Akar and Joseph Lamy, the latter having already invested in the Taximètres Unic de Monaco business with Bizet and Rothschild. There was now sufficient finance for a new factory to be built at Puteaux, which in turn allowed for production to meet the demand, and Lamy took on the role of Commercial Director. The Type B, a larger 4-cylinder model, followed in 1912. Rated at 10CV and priced at 6,000 francs, this was also a lot of car for the money compared to the competition. The Type C appeared soon after, another smaller 4-cylinder car with a lightweight two-seater body. Luckily, the military also approved of these strong but light and nimble cars, resulting in orders for 40 cars per month for army use, which meant Le Zèbre was one of the few car factories continuing to make cars through the war while also having to adapt to manufacturing hardware and machinery for other military supply contracts. Moving again to a bigger factory at Suresnes in 1914 to meet the demand, Le Zèbre also rented a small workshop owned by a Monsieur Borie at 34 Rue du Chemin-Vert near the Bastille and established the head office and showrooms near the Champs Elysées, the preferred sales area for all car manufacturers of note.

Through the war Jules Salomon remained in charge of production under the Service Technique des Arméés, which is how he was introduced to André Citroën, who had become a major supplier for the army by a mutual acquaintance, a M. Nieder. As early as February 1917, Citroën had asked Salomon if he could come up with a design for a small car, but at the same time Salomon was becoming frustrated by Bizet’s lack of direction for any post-war plans and took a position with Charron responsible for their army contracts. This did not last long, as his discussions with Citroën resulted in Salomon being recruited by the latter in July the same year to head the design office in charge of the new models planned for when peace returned.

In 1919 several changes were made to the management at Le Zèbre; Jacques Bizet resigned as a director though retaining a financial stake in the company now registered as Société Anonyme des Automobiles Le Zèbre, and new management was installed under administrator Albert Hainon, who had been one of their major suppliers since the beginning in 1909. The Type D, another 4-cylinder, this time rated at 8CV, was launched and André Morel was taken on as sales manager for the south of France. Morel had been employed as a test driver at Berliet and brought valuable experience too, but when engineer Edmond Moyet left to join Salomon at Citroën where he had responsibility for the design of the new 5CV Type C, it would soon be the beginning of the end for Le Zèbre. Morel himself would be moving on in early 1921 to what would become Amilcar. Meanwhile, Le Zèbre tried again with the Type Z, the chassis for which were assembled ironically at the Amilcar factory, but sales dwindled and the marque finally closed its doors in 1931 after producing a total of around 9,500 cars since 1909.

JULES SALOMON, 1873–1963

Although never an employee of Amilcar, Jean-Marie-Jules Salomon obviously had quite an influence on the design of the early cars.

Jules Salomon.

He was born 1 February 1873, in Cahors, and graduated at the School of Commerce and Industry in Bordeaux. From there he started his career at engine manufacturers Rouart Brothers. He then worked at several other jobs, apparently impatient and unable to settle down (the shortest stay of his career was two hours at Delaunay-Belleville), before arriving at Georges Richard, where he met Jacques Bizet (son of composer Georges Bizet). The pair formed a partnership in 1909 to manufacture his new car design, which became Le Zèbre.

The first model, Type A, was well received and attracted investment from businessmen Émile Akar and Joseph Lamy. Further models were also successful and during World War I they secured contracts to supply the army. Salomon, however, was a hardworking and pragmatic engineer while Bizet was reported to be too easy going and lacking discipline, so it was no surprise that they eventually went their separate ways.

After a brief stay at Charron, Salomon joined André Citroën’s new company in charge of designing the new Types A and B models. The smaller Type C, the design of which he had delegated to Edmond Moyet, became very successful and was to have an influence on the Amilcars that followed.

In 1925 Salomon found his power and influence diminished, as the company had adopted the American Budd system of making all-steel bodies, and he left Citroën. Not to be unemployed for long, he was then hired by rival Peugeot, but that only lasted two years when he moved again to Rosengart, where he remained until 1939.

He also found time around 1927 to make a prototype of another light car to be built under his own name. The little two-seat Salomon was based on a Rosengart LR2 chassis and powered by a two-stroke single cylinder engine of 386cc with a basic aluminium body, a curious return to the now out of fashion cyclecar principles. Presumably plans to produce copies never eventuated and the sole prototype, which was not registered until 1931, still exists in a museum in France.

Despite offers of work after peace returned in 1945, Salomon remained retired to pursue other interests. He died on 31 December 1963, in Suresnes.

Citroën

There was, however, one other engineering company that invested their war profits wisely by entering car manufacture with new ideas and modern designs. André Citroën had ambitious plans. Profiting well from the war, Citroën now had a large well-equipped factory at the Quai de Javel on the banks of the Seine in the west of Paris. At the height of the war, the Quai de Javel factory was turning out more than 35,000 shells every day, staffed with over 12,000 workers. With his previous experience with the Mors company and influenced by his visit to the Ford factory in Detroit in 1913, he decided as early as 1916 that he would enter the automobile business as soon as peace returned. Initial plans were for a larger 18hp model, possibly to be sold as a Mors, to be drawn up by Ernest Artault and Louis Dufresne, who he had poached from Panhard, but this was soon shelved, and that design was sold to Gabriel Voisin as the basis for his new C1 model in 1919. Citroën had a change of heart, reportedly on the advice of his doctor, who reminded him how many lives ordinary cheap cars had saved during the war and, learning from the Ford example, he decided a small practical and reliable car that could be produced in large numbers from the start was what the market wanted. With a smaller 10hp engine designed by Jules Salomon, Citroën came up with the all-new Model A. Announced to the press in March 1919, the first examples left the Quai de Javel factory in May that year, soon establishing the marque as one of France’s most successful.

Salmson

On a smaller scale, Salmson had also been a major player in the supply of war materials, making complete aircraft as well as supplying thousands of aircraft engines, and they too entered the car market in 1919, initially building the small British GN cyclecar under licence. We will return to Salmson later.

THE 1920s

Citroën and Peugeot continued to grow their market share with their small-to-medium models, Renault continued to offer a wider range, also sticking with their larger 40CV, while many of the other marques that were slow to adapt to the changing times after the war would be less fortunate and eventually disappear. Others with more modern ideas would soon step up to replace them.

So now the scene is set for the optimism that returned to the French people and a market developed for a new type of small but lively car that would soon populate the roads, and in many cases, the racetracks of the country.

While working for Citroën designing the new 5CV under Salomon, Moyet had also been busy drawing plans for another new car. It is probable he had started this in 1919 or earlier with Salomon for what would be a new model for Le Zèbre, but after moving to Citroën, he continued to work on this secret project in the evenings at home. The new design was for a light car smaller than the Citroën 5CV, with some similarities to the previous Le Zèbre Type C, to be powered by a 4-cylinder side-valve engine; it seems the chassis and engineering drawings were already well advanced by 1920. A commonly repeated story has it that André Morel was introduced to Edmond Moyet at the Excelsior Restaurant in Paris by Voisin dealer Maurice Puech. However, Morel had joined Le Zèbre late in 1918 after the war and other sources suggests Moyet was already working at Le Zèbre at that time and only left to join Salomon at Citroën in 1919, so it is probable that they already knew of each other.(1) Whatever the truth of that meeting, Morel and Moyet discussed the latter’s design for a new car and plotted how to get it into production. Morel, an experienced salesman by this time, had ambitions of becoming a racing driver, and Moyet probably also saw some sporting potential in his new machine; it would appear the two got along well.

Morel knew he needed some solid finance to get the project going and presented his case to Akar and Lamy, whom of course he already knew as the backers of Le Zèbre. The pair were impressed by the case presented by Morel and Moyet and agreed to support the project. To finance the new company Akar and Lamy convinced some of the Le Zèbre dealers to join them in the new venture, raising initial capital totalling three million francs. These dealers were represented on the board by M. Dumond of Lyon. The Dumond brothers had a successful garage business and were agents for Delaunay-Belleville, Lorraine-Dietrich, Talbot-Darracq as well as Le Zèbre. The defections of Akar, Lamy and Morel and the loss of several dealers would certainly impact the well-being of Le Zèbre. Further, the new company took over the premises previously occupied by Le Zèbre at 34, Rue du Chemin-Vert to assemble the new Amilcars.

The name ‘Amilcar’ is thought to be a contorted anagram of the two main partners’ names Akar and Lamy; according to motoring historian Paul Yvelin, this was suggested by Voisin agent Maurice Puech. Other theories have said it is a shortened phonetic version of Emil Akar, others have linked it to a play on the name of the great Carthaginian warrior Hamilcar, father of Hannibal. Whatever the origins of the name the car was initially known during 1921 as the ‘Borie Cyclecar’ after the landlord of the small factory in the 11th arrondissement in Paris. The name Amilcar was registered in the Seine Commercial Court on 19 July 1921, but it was not until September that the articles of the company Société Nouvelle pour l’Automobile (SNPA) were published with Akar named as Deputy General Manager and Lamy as Commercial Manager. André Morel had joined, taking the role of Sales Manager for the south, and at some point, in the middle of 1921 Moyet was named Chief Engineer.

The Amilcar was on its way.

JOSEPH LAMY, 1881–1947

Joseph Lamy was born in Courtomer in the Orne department of north-west France on 20 July 1881. He was the eldest son of a family of farmers. The family was poor, and with little prospect of betterment he left for Russia in 1900 in search of work.

Joseph Lamy.

He must have had a talent for languages, as he learned Russian in a few months and went on to become a professor of French at the University of Saint Petersburg. He also took up a position as a correspondent for L’Ouest-Éclair, a newspaper covering north-west France for which he submitted several reports, including an adventurous trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Macedonia and another to Korea.

Upon returning to France in 1908, he became a director of a Monaco taxi company, and the next year he joined Le Zèbre as Commercial Director, also investing some of the starting capital of the company.

In 1921, he formed a partnership with financier Émile Akar to start the new Amilcar company, taking the position of Commercial Manager and later Managing Director. At the same time, he owned a fashionable restaurant and night club on Rue Caumartin, Paris.

Despite earning great wealth, a salary said to be 300,000 francs in 1925 alone, and moving in society circles, he was not seen to be extravagant and kept in contact with the village where he was born, giving to local charities, and later serving on the municipal council; there is even today a street in Courtomer named after Joseph Lamy.

After he was ousted from Amilcar in 1927, Lamy set up business as a Hudson and Essex dealer until 1935, during which time he also entered the Tour de France Automobile with his old friend André Morel driving.

From 1935 to 1940, Lamy was interested in improving cleaner, less polluting exhaust systems and synthetic fuel (is there nothing new?), all of which caused him to lose money. He was also involved in a project to develop a Brazilian rubber forest at the mouth of the Amazon.

From 1941 to 1945, he created a gasifier business, a common practice in wartime Europe in which wood or charcoal is heated to produce gas as an alternative to rationed petrol. Using the brand ‘Le Français’ he was more successful with this project. He died on 3 June 1947, in the 17th arrondissement of Paris after an unknown illness.

ÉMILE AKAR, 1876–1940

Émile Akar was born on 27 March 1876, the son of a wealthy Parisian clothes manufacturer. His three brothers were all successful in business and he graduated from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales. He married Clémence Cahen (1892–1979) and they had one son, Robert, born in 1911. Akar’s father-in-law, M. Albert Cahen, had built up a business from selling packets of coffee on the streets of Paris, creating a coffee roasting and grinding factory and a chain of shops across France under the name ‘Planteur de Caïffa’. At some point Émile joined this business and in 1911 he also invested some capital in the Le Zèbre car company.

Before the 1914–18 war Akar also owned a horse-drawn transport company. This had been linked to supplying the coffee shops, but when all horses were requisitioned for the war effort, he established another business repairing military uniforms.

Émile Akar.

When he met Morel and Moyet to discuss the Amilcar project, he gave them 100,000 francs for the manufacture of two prototypes.

Émile Akar was very fond of luxury and the Parisian social life. A close friend of André Citroën, he was also passionate about shooting and luxury cars, and alongside the inevitable Amilcar, he also owned a Voisin, a Chrysler and a Hispano-Suiza, with a chauffeur on the staff.

At the start of the Amilcar affair, he lived in a small mansion on Rue Berlioz in Paris, but with the success of the Amilcar he moved into a large house on the Rue Jean-Goujon near the Grand Palais. He also owned a country property in Sologne.

When he was ousted from Amilcar in 1927, Émile Akar sold a large part of his property to compensate his creditors and returned to his old businesses and started some new ones, usually successfully.

In April 1936, Akar bought the Château de l’Écluse, in Salbris, Loir-et-Cher near Orléans. During World War II, Akar, being of Jewish descent, fled the Nazi-occupied north, and died in Marseille trying to escape the country on 16 November 1940. In 1941 the wartime Vichy government confiscated the chateau. This was followed by the death of his son Robert two years later without leaving any other heirs.

CHAPTER 2

1921 – THE FIRST AMILCARS

To say the Amilcar was created by the convenient marriage of a design by Edmond Moyet, the persuasive ambitions of Morel with the capital, and the business skills of Emile Akar and Joseph Lamy would be to oversimplify the case. First, there is the conundrum of Edmond Moyet’s employment in 1921, for a period certainly in the early part of that year he was working for both Citroën and his future employers at Amilcar. Since joining Jules Salomon on the design of the new Citroën Type A in 1919 (and later he probably had some influence on the Type B which replaced it in June 1921), Moyet alone had been tasked with the design of the Type C, although Salomon probably once again designed the engine.This was to be a small car rated at 5CV that was to prove very popular, with over 80,000 examples sold between 1922 and 1926.The Citroën Type C was launched at the Paris Salon on 6 October 1921, all within the timeframe of the gestation of what was to become the Amilcar CC, which must have kept Moyet busy.The basic design of the engine for the new Amilcar at least was ready first, probably also started by Salomon when still at Le Zèbre, but nevertheless Moyet must have been burning some midnight oil to see both projects through.

Records do not say exactly when Moyet left Citroën, but by the time the new Amilcar appeared at the same Paris Salon in October he was an employee of the new company. Akar and Lamy appear to not have been bothered by taking their respective investments out of Le Zèbre while at the same time poaching their dealers. They must have preferred what they had seen of Morel and Moyet and the design of the new car over the existing situation at Le Zèbre. Similarly, taking over the workshop premises at 34 Rue du Chemin-Vert from the latter did not appear to trouble anyone’s conscience. The date of the meeting of Morel and Moyet at the Excelsior restaurant is not recorded, but it was most likely in 1919 with the business partnership agreed and work on the prototype starting in 1920 and the name Amilcar registered by July 1921.

Keen to get going, things moved quickly, recruiting Henri-Georges-Jean Renoult as Technical Director and design staff to work under Chief Engineer Moyet in the drawing office. A significant addition to the team was Marcel Sée, brought in by Akar as Deputy Manager; Sée had already formed a coachbuilding and upholstery business in partnership with his cousin Gilbert Nataf, which they named Margyl as a contraction of the pair’s first names. Marcel Sée would play an important role later in the Amilcar story. In what was thought to be a first for a woman in the automobile industry, Joseph Lamy’s wife Thérèse was appointed General Sales Manager. Mechanics and engineers were hired to start building the first three cars under Production Manager Edmond-Louis Delmer. The articles of the parent company Sociéte Nouvelle pour l’Automobile were published by Parisian notary M. Barillot on 29 September 1921. As well as Akar and Lamy, officials included Akar’s brother Jean and publisher Michel Calman-Lévy. Initially, the prototypes were called the ‘Borie Cyclecar’, so one could wonder if the owner of the factory had any financial interest in the new company or possibly this was just a temporary convenience while future plans were still being decided. Whatever the reason for the name, by the time of the Salon in October they were officially launched as the new Amilcar CC – the CC part of the name referring to the cyclecar identity.

The 16th Salon de l’Automobile opened on Thursday, 6 October 1921, and ran for ten days at the Grand Palais, a large glass and steel exhibition hall situated between the Avenue des Champs-Élysées and the River Seine. Opened in 1900, this was home to the annual motor shows from 1910 until 1961 and in the rush of post-war optimism the 1921 Salon was a popular attraction with many new models to tempt the public.

EDMOND MOYET, 1893–1954

Edmond Paul Moyet was born in Toulon on 30 March 1893. Moyet began his career as a draughtsman at Borie & Cie and collaborated with Jules Salomon on cyclecar design for Le Zèbre.

After Salomon went to Citroën in 1917 to head the design department, he recruited Moyet to join him. While Salomon was responsible for the first Citroën models, the small 5CV Type C is credited as the work of Moyet, who worked at the research department in the Rue du Théatre alongside Salomon. The 5CV filled a gap in the market for a small car somewhere between a cyclecar and full-size automobile. It was immediately successful, selling about 80,000 examples between 1922 and 1926.

Edmond Moyet.

Moyet left Citroën to take charge as Chief Engineer at Amilcar some time in 1921, which must have been a busy year for him. Both the 5CV and the Amilcar CC were presented to the public for the first time in October 1921 at the Paris Salon.

Moyet left Amilcar in 1934, along with many other staff when Marcel Sée closed the Saint-Denis factory in August of that year, and he returned to work at Citroën taking Marcel Chinon, former head of the drawing office, to start work on the design of what would become the legendary 2CV under Pierre Boulanger and André Lefebvre.

Moyet was granted a few patents, two published on 24 July 1929: FR-661360-A for ‘Improvements to the control devices for the rockers and cam valves of internal combustion engines’ and FR-661361-A for ‘Improvements to internal combustion engines including those fitted in motor vehicles’. Another on 28 February 1934 was published as FR-760670-A for ‘Improvements to chassis of vehicles including motor vehicles’.

Moyet died in Paris on 9 November 1954.

ANDRÉ MOREL, 1884–1961

André Paul Victor Morel was born on 3 August 1884, in Troyes in the Aube department. The family lived nearby in Buchères, but he lost his father at the age of eleven. There were plans for him to be a priest or a butcher, which came to nothing, and he joined a local garage as an apprentice but did not settle and then cycled to Paris by bike finding work as a porter at Les Halles in Paris.

André Morel.

Morel next signed on as an apprentice mechanic with Corre in Levallois. He then cycled to Lyon, but without qualifications he had again to take on menial jobs. Luckily, while working as a used car salesman he was recruited to work at Berliet and was soon chief test driver for their 40hp bus chassis. He must have made a good impression, as he was also taken on as Marius Berliet’s chauffeur.

At last, with some experience, he moved back to his native Aube region and in 1911 opened a garage where he became an agent for Berliet and Le Zèbre and started a bus company. The buses were taken by the military for war use but Morel himself was rejected as unfit for combat, so he returned to Berliet where the factory was turned over to making armaments and shells. He tried again and was accepted by the aviation service and soon was a qualified pilot – presumably a good one too, as he was promoted to an officer rank and became a flying instructor.

Peace eventually returned and, on 1 April 1919, Morel was hired by Le Zèbre as sales manager for 40 départements in the south-east of France. There were potential buyers and the marque still had a good reputation, but there were delays with making enough cars. Additionally, as inflation was rampant prices were rising while customers were still waiting for delivery, causing many orders to be cancelled, which was not an easy situation for a sales manager.

Morel also had ambition to get into driving competitively and possibly his first outing was at the Limonest hillclimb on 24 April 1921 in a D type Le Zèbre. His subsequent move to Amilcar is covered elsewhere, and on the circuits he had many successes with the Amilcars, Delages and Voisins without too much pain, the worst injury being burnt feet at the 1926 San Sébastian in the Delage. He also set speed records with Voisin.

When Amilcar finally closed the competition department in 1929, Morel left to work for his old partner Joseph Lamy selling Essex and Hudson cars. Thus, it was inevitable that Morel would start racing these marques with many class victories over the next two years. After a short spell at Minerva, Morel was hired by Talbot as head test driver and later helped with developing the very successful T150C, finishing third (with Jean Prenant) in the Le Mans 24-hour race in 1938. Morel raced again at Le Mans in a 4.5-litre Talbot coupé in 1949 and 1950 and an open-bodied T26GS for the next two years, after which at the age of 68 his family persuaded him to retire from racing.

André Morel died in 1961 in relative obscurity at the age of 77 in Lyon following a short illness, but is now remembered as one of the great racing drivers in his home country. Conflicting records suggest the date of his death was either 17 July or 5 October.

THE AMILCAR CC

Designed to fit the new regulations to qualify as a cyclecar, the first Amilcar was a true sports touring car in miniature with no unnecessary extras, although a customer could order such things as a spare wheel to be fitted after the car had been weighed at under 350kg for tax purposes. Most of the small cyclecar companies that proliferated around Paris at the time were making rather crude machines. Many of them merely assembled a collection of bought-in parts and used proprietary engines from several suppliers, the most common being Anzani, Chapuis-Dornier, the wonderfully named Compagnie Industrielle des Moteurs à Explosion (CIME), Ruby and Société de Construction Automobile Parisienne (SCAP). Briefly after the war, there were many more crude light cars built using military surplus supplies of American Harley-Davidson and Indian V-Twin motorcycle engines. Immediately distancing themselves from such machines Amilcar had planned from the start to make the entire car, save for a few accessories, in house. The basic concept was not too far removed from the previous Le Zèbre, so the Jules Salomon influence was evident, even though he was never an Amilcar employee.

Amilcar CC bare chassis as shown at the Paris Salon October 1921.

The CC was powered by a simple 4-cylinder engine not too dissimilar to the existing Le Zèbre and new Citroën designs with the same 55mm bore, two-bearing crankshaft and side-valve cylinder head but with a one-piece cast-iron cylinder block and crankcase. The 95mm stroke gave a capacity of 903cc rated at 17hp. This was in unit with the three-speed sliding pinion gearbox and three-plate clutch sharing the same oil as the engine. With no pressurised oil pump fitted, lubrication to the engine components was provided by the flywheel lifting oil up into a reservoir that supplied gravity-fed troughs that fed the big-end and main bearings. This worked well enough as long as a constant oil level was maintained in the sump. The quoted power output was 17hp, although by the French tax system it qualified as a 6CV, the CV being shorthand for ‘Chevaux Vapeur’, the archaic nineteenth-century formula for rating the horsepower of steam engines. Cooling was by thermo-syphon with no water pump, effective enough if there was some forward movement providing airflow to the radiator. The radiators were supplied by either Chausson or Gallay and were initially made in one piece so the outer shell was sealed to the core as an outer water tank. These were soon changed to a sealed radiator comprising a core with soldered top and bottom tanks surrounded by a separate nickel-plated shell. Final drive was via a cardan shaft enclosed in a torque tube to the rear axle. This too was a simple design with no differential, which was considered unnecessary due to the narrow 109cm track and bicycle-thin section tyres allowing enough slip when cornering without significant resistance. In fact, it was also an advantage on what were often rough roads of the time, as braking was available on whichever tyre had contact with the surface at any given time. The simple crown wheel was held on to the one-piece axle shaft by a keyway and early cars had straight tooth bevel gears. The rear axle casing comprised a cast aluminium housing with a pair of trumpet casings bolted each side which held the brake backing plates at either end. Braking was by the rear wheels only, with ribbed cast iron drums, which were operated one side by the foot pedal and the other by the hand brake; of course, with no differential both had the same effect on both wheels.