45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

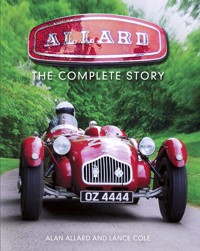

The remarkable story of everything Sydney Herbert Allard achieved in motor sport and motor car manufacture is framed in an up-to-date commentary co-authored by his own son. This is a tribute unswayed by legend, but based on the facts and achievements of his eponymous company. With contributions from the Allard Owners' Club and Allard Register, this book contains painstaking research of Allard history from 1929 to the present day, including previously unpublished material. Just under 2,000 Allards were built, and approximately 510 are believed to remain on the road or known to be under -restoration. More await discovery - even as this book was being written, one of Sydney's long-lost 1930s 'Allard Specials' has been found after years being forgotten. Other topics covered in this remarkable book include: car-by-car engineering and design details; unseen ideas and projects; the history of the Allard marque in motor sport and the Allard story in the USA. Finally, it features the Allard Owner's Club, Allard Register, members and their cars.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 644

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE COMPLETE STORY

Sydney Herbert Allard, 1910–66

THE COMPLETE STORY

ALAN ALLARD AND LANCE COLE

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Alan Allard and Lance Cole 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 560 2

Photographic AcknowledgementsBlack and white period photographs are taken from the Allard family archives and former Allard Motor Company archives. Where possible relevant copyright has been researched and cited. Every effort has been made to source and credit the original photographer where possible. Other black and white and colour photographs have kindly been supplied by the Allard family, Allard Owners Club, Allard Register, AOC club members, and: L. Cole, S. Grant R. Gunn, M. Herman, A. Picariello, C. Warnes. Main colour photos on pages: front cover, 16, 18, 24, 67. 68, 73, 74, 75, 78, 79, 80, 85, 88, 93, 97, 197, 198, 199, 200, 203, 205, 208, 209, 210 and 212 are by co-author Lance Cole.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction: An Unorthodox Orthodoxy

CHAPTER 1THE EARLY DAYS OF ALLARD

CHAPTER 2ALLARD SPECIALS AND EARLY IDEAS, 1930–3929

CHAPTER 3THE ALLARD MOTOR COMPANY, 1946–66: MAKING THE CARS

CHAPTER 4THE CARS: MODEL BY MODEL

CHAPTER 5ALLARD IN MOTOR SPORT, 1946–66

CHAPTER 6ALLARD AND DRAGSTERS

CHAPTER 7ALLARD IN THE USA

CHAPTER 8THE ALLARD OWNERS CLUB (AOC)

CHAPTER 9ALLARD DIVERSIFIES

CHAPTER 10ALLARD SPORTS CARS – RESTORATION AND REVIVAL

References and Bibliography

Appendix I The Allard Specials 1936–1946

Appendix II Allard J1 (Competition) Racing Car Specials 1946–1948

Appendix III Allard JR Sports Racing Car Chassis Numbers 3401–3408

Appendix IV Palm Beach Mk 2

Appendix V Allard Car Production

IndexACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FIRSTLY, I WOULD LIKE TO GIVE my heartfelt thanks to my wife Lynda, for the endless hours spent typing my text, filing and saving on the computer, then having to make revisions to the draft on several occasions.

It goes without saying that a book of this nature, which covers such a wide range of motoring activities, spread over nearly a hundred years, needed much time and research from both Lance and I.

I thank the following people for the advice, information, text and photos supplied. If we have inadvertently missed out anyone, please accept my apologies.

Jesse Alexander; Darell Allard; Gavin Allard; Lloyd Allard; Nick Battersby; Bob Bull; Bob Francis; Walter Grodd; Mel Herman; Kerry Horan; Dave Hooper; Matt Howell; Dudley Hume; Mike Knapman; Rob Mackie; David Moseley; John Peskett; Andy Picariello; Chris Pring; Des Sowerby; Brian Taylor; Jim & Sheila Tiller; Ted Walker; Colin Warnes. Library pictures: Revs Institute; LAT Images.

Alan Allard

PREFACE

MY FATHER SYDNEY was never a nine-to-five workaday man, nor was he to be seen getting involved with my mother in the daily household family chores. Mainly, during my early childhood years, I can recall him scribbling away making notes and sketches, with his briefcase alongside, seated in his armchair by the fireside. A mystifying memory of his habit of always blowing into his shoes before putting them on made my enquiring child’s mind ask why: his reply was ‘there might be a mouse in my shoe!’

Being sent to boarding school at around eight years old was challenging for me, only being reunited with my sisters and parents at the end of term time. It was during this period 1948–54 that my father’s business and motor sport activities were at their most intense.

Sydney and Eleanor with Alan, aged nine, in the paddock at Prescott hill climb, 1949. Sydney went on to win the British Hill Climb Championship that year in his Steyr Allard.

Sydney and Eleanor posing in front of their home ‘Karibu’, near Esher, Surrey, in 1951, with the ‘M’ Type Allards that they both drove in the Monte Carlo Rally.

Sydney with Eleanor just after Sydney won the Monte Carlo Rally, 1952. Press coverage was huge.

During these years he was unable to share holiday trips to the South of France, where we rented a villa for three weeks. My mother Eleanor (who we always called Mumma), with the support of her sister Hilda, had no problem driving five children 850 miles in the Allard Safari estate down to Cannes. Mumma, in fact, was a confident driver in her younger years and with Sydney’s encouragement took part in many events: Brighton Speed Trials, various hill climbs and rallies, even competing twice in the Monte Carlo Rally with her sisters. In later years, however, she devoted herself to her lifelong interest in gardening, indeed a hobby that both my sisters and I enjoy today – all in our seventies!

From around 1955 onwards, when my father was doing far less motor sport, he drove us on a grand tour in the Allard Safari to Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway. He loved to go fishing, a complete contrast to his exhilarating racing days. He found remote spots and we often caught fish for our supper. The task of baiting the hook or gutting the fish fell to me: my fearless fast-driving father couldn’t handle worms!

He had a strong, quite intense personality and spoke quickly. He was a generous, fair-minded man with a sense of humour and liked a bit of fun. I can remember my sisters and I, probably aged between six and ten, tussling with him, trying to bring the big man down.

He had many motor sport crashes through his racing career, some where he could have suffered serious injury and even death, but as far as I know, miraculously, he never once broke a bone! Perhaps the most serious non-racing incident occurred on holiday in Sweden. When working on the Allard Safari estate car exhaust, the car partially slipped off the jack and, although he had a wheel and tyre underneath for safety, the heavy car came down and pinned his head between the ground and chassis rail. I don’t know to this day how I managed, but I was able to lift the car just enough to release his head and he only suffered a minor cut.

With the help of Ted Flint, the carpenter from the works, he built a model railway set that travelled all around the large attic at our house in Esher. I helped him build up the track. Another interest of his was stamp collecting (a far cry from racing) and later he became a committee member for the Railway Conversion League (the conversion of abandoned railway lines into roads).

During all the years spent with my father, I never once heard him swear or have a heated argument with anyone, including at home with the family. In later years, however, there was one occasion when we were doing a recce for the Monte Carlo Rally. I was a young lad, with special permission to have leave from school, sitting in the back seat, watching and listening. Tom Lush was navigating and got it all wrong. Poor Tom received a tongue lashing then, but still no swear words! I can imagine that long-suffering Tom must have gone through this scenario on other occasions during the many times he was navigating for my father.

In his approach to life he always conveyed a sense of optimism. I never saw him depressed or grumpy. He had an air of authority about him as the boss, so much so that he could motivate people to do a particular errand or job, including friends or family, without seemingly having given any specific instructions! Indeed, they might find themselves doing a task that they may not have wanted to do. His saying, ‘why have a dog and bark yourself’, comes to mind.

Every year from 1954 to 1959 we had a three-week touring holiday to the ‘Continent’ of Europe. Often it felt as if we were on a long-distance rally, often attempting to get to remote places along routes where others feared to go.

The May sisters, Edna, Hilda and Eleanor, with children (from left) Alan, Simon, John, Sally, Marion and Bill, about to set off on holiday to the south of France, the in the Allard Safari, April 1952.

The Queen Mother and Princess Margaret admiring the Allard Palm Beach on the Allard stand at the Earls Court Motor Show, 1956.

In 1957 and 1958 we had a Ford Thames van converted to a motorhome. Disappointed with the performance of the heavily laden vehicle the previous year, father decided that it had to have more hill-climbing performance, so he had a Shorrock supercharger and front wheel disc brakes specially fitted. Supercharging a Ford van just for holiday driving – who but my father would have done this in 1958!

Away from family life and the holiday escapades, he was a motor sport competitor at heart, taking part in an amazing range of motor sport events, mostly in cars carrying his own name – mud plugging trials, sand racing, Brooklands, sprints, hill climbs, autocross, rallying, circuit racing, drag racing – the list seemed endless.

Sadly, still with so much ambition, his life was cut short after losing a six-month battle with cancer. He died on 12 April 1966 at the relatively young age of fifty-six.

Such was his continued optimism and drive that, even when lying ill in bed, he insisted that Tom Lush put in his entry for the January 1966 Monte Carlo Rally.

Had he been fortunate to survive another twenty-five years, I wonder just how many more challenges he would have had a go at.

Compiling and writing this Allard story, together with Lance, has been a great experience as we revealed a treasure trove of memories concerning the motor sport activities of Allard cars and the man whose determination and tenacity were behind them all. His contribution to the motor sports arena will never be forgotten.

Alan Allard

INTRODUCTION:

Sydney with Jim Mac, his trusty mechanic, in J2X at the Le Mans 24 Hour Race.

AN UNORTHODOX ORTHODOXY

INTRODUCTION:

AN UNORTHODOX ORTHODOXY

ALLARD OCCUPIES AN INTRIGUING PLACE in the history of British motoring and a vital ranking in motor sport’s story. Today some remember Allard fondly as a brand from a time when single-minded entrepreneurs, garagistes and men in sheds created sporting cars for competitive use in motor sport specifics, such as hill climbs, trials, rallies and races. For others, Allard evokes a post-war era when powerful cars built in low numbers could be purchased directly from the factory to varying specifications and also used on a daily basis, as well as campaigned in the calendar of racing events. Allards were also set into a front-line competitive context in America, where the fame of the brand and its creator reached from Watkins Glen to high-society owners.

Let’s not forget that it was one man, Sydney Allard, who built Britain’s first true dragster and launched the American sport of drag racing in a British context. We might wonder then why so many people have never heard of Allard? Many have, of course, but there is a ‘gap’ even among motoring enthusiasts.

Allard means different things to different people, yet one thing is constant: Sydney Allard, his band of men and the cars that bore his name shone on the national and world stages to a degree that was significant in the tide of automotive affairs. Allard expert, restorer and serial Allard owner John Peskett sums it up very accurately: ‘For a brief period, Allard really was the one of the top motor sport names in the world.’

This is no idle boast. It is a very real truth that might be hard to grasp more than sixty years since it was headline news, but it is true. Sydney Allard went from ‘backyard built’ trials specials to production cars and dragsters via the international stage and its winners’ podiums.

Sydney attempted to drive his Allard Special CLK 5 to the top of Scotland’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, but failed when the car rolled off the track.

At Le Mans in 1950 Allard was third overall and Sydney himself had led in a car bearing his own name. So Allard’s name was splashed all over the newspapers for all the right reasons. Sydney, his exploits and latterly his cars had a national and overseas profile in big headlines. An Allard J2X model was featured in the famed Eagle magazine on 13 June 1952. It was Sydney Allard who beat Stirling Moss in the Monte Carlo Rally. It was Sydney who overtook Fangio (in a Cooper-Bristol) in the Chichester Cup at Goodwood – Fangio overtaken by a bespectacled gent in a tweed jacket and a tie!

As the respected writer and commentator Simon Taylor said in Classic and Sports Car in 1996: ‘The Monte Carlo Rally caught the attention of the British public every year.

British winners became heroes and Allard in 1952 was the biggest hero of all.’

The unique Steyr Allard became the 1949 Hill Climb Champion with hill records and many wins. This factory publicity shot shows some of the employees gathered behind the trophies and the car.

Surely the fact that Sydney was more of a ‘normal’ bloke than most upper-crust or well-heeled drivers of the era, who worked on and drove his own race cars, underlines the reason why Sydney was so loved by the British public and press alike. And who else but Sydney would supercharge a Ford Thames van back in 1958?

Simon Taylor also recently pointed out that those who modify their classic Allards are not committing sacrilege: ‘After all, if it makes the car faster, do it – Sydney would have approved.’

There is of course a point to be made that, given how rare Allards are now and how valuable some have become, we should aim at preserving the original specification, keeping the cars on the road and maintaining the ownership. The days of wiping out absolutely everything in a stripped bare, new-for-old total classic car restoration must be over, since a new old car is not a true old car,

The basic fact, however, is that speed – competitive speed – was what Sydney was focused on from 1928. This remained the case, probably at the cost of much else.

The recent words of Sir Stirling Moss about Sydney to David Hooper, the chief draughtsman at the Allard Motor Company, frame Allard’s achievement and the esteem in which he was held: ‘I knew Sydney Allard quite well, and competed against him many times in rallies and races. He was a very fast and pretty fearless driver, and also a very nice man.’1

Tony Mason, a top rally navigator and a mud-plugger driver, reckoned that Sydney Allard was fearless and the only driver he had ever met who actually liked driving in fog.

Cyril Wick drove Sydney’s modified, lightweight J2 and broke the 40 seconds barrier at Shelsley Walsh for the first time in the hill’s history. He also beat Jaguar’s famed driver Norman Dewis in an Allard versus Jaguar head-to-head at the Brighton Speed Trial. Further proof, then, that Sydney and his Allards were the stars of their day.

We should never perceive Sydney as an ‘enthusiast’, nor see Allard as a ‘cottage-industry’, ‘kit-car’ producer. Whatever the cars’ ‘parts bin’ oddities, Allards were true low-volume production vehicles produced in a professional manner on a form of production line that was typical of its era and context, if not of today’s perceptions.

The key fact in Allard’s success was that the product defined the brand, not the other way around. It was an added ingredient that Allard the man defined his products. As Autocar stated back in the 1950s, the Allard J2 ‘might be described as the finest sports motorcycle on four wheels ever conceived!’ While Donald Healey’s marque achieved great success, it was Sydney Allard who beat Healey’s Cadillac-powered Silverstone at Le Mans in 1953 and finished third overall. This helped make him big news in the British motoring world in the 1950s.

In America in the early 1950s Allard was one of the ‘big three’ British sports car manufacturer names: Jaguar, MG and Allard. Few people know just how close Allard came to doing a vital 1950s US deal with Dodge, or with the Kaiser company to market a glass fibre-bodied Palm Beach Mk 2. American sports car enthusiasts really took Sydney and his cars to their hearts and Allard was so close to a new chapter, yet the company was to be the victim of several circumstances.

Dean Butler, the dedicated American Allardiste, recently summed up Sydney very neatly: ‘Sydney Allard was a Californian hot-rodder who happened to live in England!’

After a period of great success on the track and on the road, Allard’s star faded as times changed. The larger car manufacturers, notably Allard’s rivals, moved into the new late 1950s world of mass production, economies of volume and scale, and expensive design research resources. Smaller British, European and American car brands, all once famous names, died out. In the early 1960s Allard also succumbed as a car maker, although the company and the family have remained involved in engineering and motor sport to the present day.

The era of specialist, hand-built, powerful, separate chassis cars with ‘grunt’ was passing, even though the likes of the AC Cobra and various American ideas survived for a time in a new automotive world: Carroll Shelby drove, raced and studied Allards long before he created the Anglo-American AC Cobra, a car of similar ‘grunt’ context. Elements of the Allard designs may also be found in the origins of the Corvette.

Sydney Allard’s achievements at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, winning the Monte Carlo Rally and taking the British Hill Climb Championship, as well as selling nearly 2,000 cars to customers all over the world, are not completely forgotten. Beyond the world of the Allard enthusiast and the classic car fan, however, such achievements have become obscured by time and are perhaps almost unknown by a younger generation of ‘petrol heads’ or ‘gear heads’, as they are termed in the USA.

Sydney Allard receives his Monte Carlo Rally winners trophy from Prince Rainier.

Sydney in his new dragster chassis, without its clothes!

The Allard cars of our story stem from an age before drive-by-wire digital authoritarianism intervened in our cars, which has largely separated man from the mechanical act of driving. Today the driver of a computerized supercar, enhanced by electronic intervention in its steering, gearbox, suspension, engine management and throttle response, perhaps even with ‘fake’ exhaust sound piped into the cabin, can park up at a classic car event at a historic venue, such as Prescott, Shelsley Walsh, Bo’ness, Goodwood, Le Mans, Pikes Peak, Pebble Beach, Sebring, Phillip Island, Geelong or Lime Rock, and then watch a real, oily ‘car’ – as once was defined by that word – being commanded by a man or woman using physical and mental abilities in a true act of driving. Allard cars and Allard drivers have no place for digital systems and synthetic ‘stuff’. They are about the mechanical act of driving.

Many exploits coloured Allard’s rich American history across the decades, right from the day Erwin Goldschmidt won the Watkins Glen Grand Prix in an Allard J2 in 1950. Burrell, Carstens, Cole, Duntov, Fogg, Tiley, Shelby, Wacker and Warner are just a few of the illustrious names on the roll call, but how many people know that Cameron Argetsinger, who founded the original Watkins Glen races, owned a 1951 Allard J2? The 1950 Allard J2s were so dominant in America that Ferrari, beaten on the track and to the podium by Allard, had to increase its engine size and create a new more competitive model to fight back and regain its credibility. More recently the Allard Register has been at the centre of interest in the USA, and Allard enthusiasts have held a series of ‘Gatherings’ at race meetings where many have competed.

Wherever you look, Allards were there, then and now.

The Allard and its origins lies in a complex set of circumstances and design characteristics that created the Allard marque, a gestation and lifespan that ranged from about 1928 to 1959. From those years came not just a unique range of cars, but also a record of competition driving and victories that are legends in the annals of motor sport. A modern major car-maker who enjoyed such a record would be splashed across the media backed by a multi-million pound marketing budget. Back about 1950 Sydney Allard and his team just got on with it, earning their place in Motor Sport and across the motoring and national media by their results, not by paid placement. And this was against such famous drivers as Stirling Moss, Peter Collins, Carroll Shelby, Briggs Cunningham and Alberto Ascari, and so on down into the club men and the ranks of amateur enthusiasts.

Even after all this time Sydney Allard remains the only man to have competed in and won outright the Monte Carlo Rally in a car of his own design and manufacture. This was in 1952, when he won with Guy Warburton co-driving and navigator Tom Lush, beating Stirling Moss in a works Sunbeam Talbot. He also competed four times at the Le Mans 24 Hours doing the same thing, sometimes driving there in his race car. His best result, third overall in 1950. These were incredible feats for a team who did not boast the resources of major marques such as Ferrari, Alfa Romeo or Jaguar. All of this was achieved in a car of his own design and bearing his own name. When you add in his victories in the 1949 British Hill Climb Championship and many regional events, Tony Hogg’s description in Road and Track in July 1966 sums up Sydney Allard’s legacy: ‘An achievement unique in motor sport, and a tribute to his persistence, ingenuity and resourcefulness.’2

Fearless Sydney ‘flying high’ in the Steyr Allard at the top of the Rest and be Thankful hill climb, 1949.

The pre-war ‘Allard Specials’ period saw Sydney on a hectic schedule of national events that included trials, circuit races, rallies, hill climbs and sprints, but this was little compared to the years from 1947 to 1953, when he would spend hours driving to compete at events, all while running the Allard Motor Company and a rapidly growing Ford dealership.

This is not a tale of smoke and mirrors, a brief puff of bold claims followed by bankruptcy after failing to produce more than a single car – a scenario so familiar to motoring observers when someone says that they are going to start making cars. Allard made a total of just under 2,000 cars and for a short period was a big British success. The death of the Allard brand by 1960 was not the result of profligacy or incompetence, but rather the result of difficult decisions amid changing circumstances in a developing marketplace. Yet for a period spanning less than two decades, one man and a band of brothers operating from several south London workshops not only took on the greats, they created a niche marque of unique cars that truly found a place in the nation’s affections and wherever Allards competed across the European racing calendar. Allard in America remains a vital story and the marque’s place in Australia and South America should not be forgotten.

An essential question must be: what is an Allard? How and why did the cars become what they were? Ultimately, we might well ask, how did the once famous tale of Allard and his cars become confined to the world of classic car enthusiasm, consigning a massive public and PR profile of worldwide fame to distant memories? The remembrance of Allard faded in the years after it ceased making cars, but just sixty years ago Allard was a household icon, a great British brand and a major name. Members of the British Royal family were seen on the Allard stand at the Earls Court Motor Show and numerous celebrities owned Allards. Allard had a massive profile and so did Sydney, the driving force.

Sydney’s wife Eleanor, seen here in a J2 at Prescott, was a great asset to Sydney, rallying and racing many of his Allard cars.

1929 – Sydney aged 19 on the start line at the famous pre-war Brooklands banked motor racing track. The threewheel Morgan was classed as a motorbike. Starting last on handicap, Sydney went on to win, this his first circuit race.

Both the name of Allard and its recognition as a car brand is now resurgent with the family’s launch of cars that are not re-creations, but continuations of Sydney’s thinking, through the activities of his son Alan and grandson Lloyd (with his brother Gavin curating the brand’s archive). Darell Allard, the son of Sydney’s brother Leslie, also figures in today’s Allard scene and is a key contributor to maintaining the profile of the cars and the owners’ club. Darell’s late brother Terry followed in the family tradition as a motor sports man, motorcycles being his thing; he was best known for his scrambling exploits as a top national rider in his youth. All the Allard family, from sons and grandsons to cousins, remain Allardistes.

This, it seems, is a story full of questions. Everyone has heard of the Aston Martin series, Morgans, MGs, Triumphs, Austin Healeys or Jaguars, quintessentially British national icons that rank with the institutions of the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, Avro Lancaster and the Concorde. And what of Americana and the Shelby AC Cobra, the Ford Mustang and other ‘muscle car’ delights? What of Italian exotica and racing Maseratis and Ferraris? Yet alongside these legends, there was once a car and a man of perhaps equal fame that captured an essential essence of British design and motor sport: Sydney Allard was that famous, and so were his cars.

Just under 2,000 cars sold on the global stage was a huge achievement for any small company, let alone a post-war ‘start-up’ brand whose competition success, and the public profile that it inspired, was mostly down to the founder himself.

Two decades ago about 700 Allards, from wrecks to restored cars, were known to survive, but recent research by ex-Allard employee David Hooper and the Allard Owners Club suggests that 507 Allards are known to remain in one piece, scattered across the globe in various states of splendour or disrepair. It is possible that the remains of another ten, twenty or perhaps fifty may exist worldwide. Two J2s, for example, were recently discovered under a bush in America as ‘yard finds’: there could be more.

The prices that some Allard models have achieved have been interesting, up to about £500,000, yet others can be had for well under £50,000. Overall many Allard prices have been rising and interest remains gratifyingly strong, at least among dedicated Allardistes. Even Wayne Carini, renowned classic car restorer and star of his own TV series Chasing Classic Cars, has purchased an Allard for his personal pleasure: Bill Bauder’s J2X. Allards still race during the Monterey car week and at other annual gatherings, proving that interest in Allards in America continues to this day.

Allard’s claim to be ‘Britain’s premier competition car’ was based on the output from a number of small works sites in south London, not the better-known locations such as Brooklands, Feltham, Malvern, Coventry or Bristol. But Allard’s reputation was significant: we should not forget that by 1948 Allard was producing between eight and ten cars a week, a significant figure for a small-scale car manufacturer, let alone one in cash-strapped, ration-book Britain. In fact the largest number of Allards produced in one month was forty-five in July 1948: two cars a day.

One of Sydney’s unseen sketches for a 1950s sports car development. He was always sketching and planning new cars, exploring new variations using existing, proven and cost-effective parts.

The impressive engine in Chris Pring’s J2.

In its heyday the Allard Motor Company was on its way to becoming a British icon with a celebrity client list that modern marketing would have loved. We can safely assume that nothing could have been further from Sydney’s intentions: customers were customers, and racing was racing! And racing was Sydney’s priority, probably at the expense of other elements in his life.

We should not forget that the likes of Carroll Shelby and Tom Cole raced Allards, and that Steve McQueen owned one. A gathering of assorted Allards at Watkins Glen became a regular event, such was the allure of Sydney Allard’s cars. A 7-litre Chrysler ‘Firepower’ engine in an Allard J2 lightweight must have been a deeply moving sight and a great experience from the driving seat.

Several major commentators and writers on motor sport and the wider motoring world have been Allard fans, including Douglas Blain, Tony Dron and Simon Taylor. Today there is a healthy and growing worldwide interest in Allard, backed by an enthusiastic owners club, which was founded in 1951 with Sydney’s personal support. The Allard Register has helped maintain Allard’s reputation in the USA as something of an icon among those in the know, with a particular emphasis on the J2, J2X, K2, K3 and JR models. The resurgence of Allard at club level proves that true, race-winning design, performance and individuality never go out of fashion.

Allard enthusiasts, sometimes known as ‘Allardistes’, have strong opinions about which model is the best, or perhaps the ‘purest’ Allard car when it comes to reflecting its progenitor’s ethos.

Chris Pring, owner of the ex-Titterington Allard J2 and current editor of the Allard Owners Club magazine, frames an essential issue:

The Allard Motor Company was a star that shone brightly for a handful of years in the late 1940s, early 1950s. It is fair to say the enthusiasts and motoring press couldn’t get enough. But, like many others before and since, that star has faded and been eclipsed by better resourced operations, some of which survive as the giants of today. There is no doubt that Sydney Allard left a fantastic legacy but each generation of the Allard community has a challenge: how do we educate them in matters Allard? Simple: race them, drive them, show them, share them, write and talk about them. Do that often and the Allard star will keep its glow.

This iconic ex-Desmond Titterington J2 spent many years in India. It has been beautifully restored with Ardun OHV heads on the Ford V8 and is owned by AOC news magazine editor Chris Pring.

This classic eye-catching American Allard K2 belongs to Andy Picariello, Allard Owners Club Vice President, who has long been associated with the promotion of the Allard legend in the USA.

This book is the first major work on Allard for several decades and the only story co-written by a member of the Allard family. The rightly respected books by Tom Lush and David Kinsella are long out of print and there is a place for a new perspective on the Allard story. It is hoped that this book will help to draw in a wider and younger audience to the achievements and exploits of Sydney Allard. Times may have changed, but the passion for cars has not.

Alan and Lloyd Allard in the Palm Beach Mk 2 that they restored in 2016 as a step towards the revival of the Allard car marque.

While the book will cover the main outline described in the earlier narratives of the Allard history, it will broaden out to encompass an even wider range of Allard designs and activities. Sydney’s family have told it how it was. From the mid-1920s to the present day, which has brought a new Allard family-built car, the intention is to present a commentary of interest to the classic car world, enthusiasts, drivers and racers of Allard cars.

This new Allard book covers old themes from new angles, with previously unpublished content and a fresh perspective provided by Sydney’s son Alan Allard, who has spent a lifetime engineering, driving, racing and fettling cars, and by Lance Cole, designer, motoring writer and Allard enthusiast. Together they offer not just an up-to-date commentary, but a new reference point for a new generation. The narrative is therefore in joint hands, with Alan’s personal recollections adding another dimension to the tale. Sydney’s grandsons, Lloyd and Gavin, have also added their thoughts, as have Mike Knapman and Andy Picariello at the AOC and Colin Warnes at the Allard Register – all true Allardistes who deserve due credit and thanks.

The authors hope this text leaves a reference point for Allardistes, enthusiasts, ‘mud-pluggers’, ‘tail waggers’, ‘slime stormers’ and new converts or discoverers of the brand, and that all readers will find old and new themes, ranging from engineering and design to motor sport, and across every aspect of the inspiring story of Allard. How one man and a handful of helpers created a prominent British brand is the stuff of legend. It is a great British tale, a part of automotive history that should not be forgotten.

Sincere acknowledgement must go to the Allard Owners Club, the Allard Register and the many Allardistes who have allowed important material to be cited.

So here is the story of how Sydney went from overalls to overcoat, but always kept his head under the bonnet. The authors hope that, just like the cars, this tale reflects the fun to be had in an Allard and leaves you an admirer of the marque and the man who made it.

Alan Allard andLance Cole

16 May 1936 – Sydney on the banking at Brooklands in his first Allard Special CLK5.

CHAPTER 1

THE EARLY DAYS OF ALLARD

SYDNEY HERBERT ALLARD was born on 10 June 1910 in Streatham, southwest London. He was the second of five children, his elder brother being John Arthur Francis, known as ‘Jack’. After Sydney there came two twin brothers, Dennis and Leslie, followed by the youngest Allard, Mary, the only girl. All the boys were educated at Ardingly College in Sussex. The unusual name ‘Allard’ may have Dutch or Flemish origins: it can still be found in telephone directories in the Netherlands, Belgium and France as Allard or its variant,Allaert.

Their father, Arthur William Allard, was a director of Allard and Saunders Ltd, and a successful master builder and property owner, who was consulted by the architects during the building of Guildford Cathedral. The flats that Arthur built in the 1930s at Millbrooke Court on Keswick Road, Putney, however, were bombed by the Luftwaffe during the Second World War.

Unlike some of the aspiring British car manufacturers and racers of that era, the young Sydney did not come from a privileged family, as the Allard family were not from the upper crust or old money. Instead they came from farming stock and for several generations had been agricultural workers based at Upper Deverill in the beautiful Wylye valley in Wiltshire, between Warminster and Mere. The decline in agriculture in the late Victorian era, following on from the effects of the war in the Crimea and social change, saw the Allard family move to London to seek more secure employment. Sydney’s father had trained as a slate layer and general builder before he used his intellect to establish his own small business. So the Allards knew about hard graft, even if they would go on to live a comfortable post-Edwardian existence with a view over Wandsworth Common.

In the early 1930s, just before building his first Allard Special CLK 5, Sydney campaigned a Ford TT in trials events. The TT had been part of a Ford-supported team effort prior to sale.

At the time of his birth the family lived at 25 West Side, Wandsworth Common, but Sydney was to grow up in a house named ‘Uplands’ in Leigham Court Road, Streatham. The 1911 Census shows that also living there were a cousin named Phillip, aged 16, and a domestic servant called Lizzie Cole. Arthur Allard’s Allard's job was stated as ‘Slate Trade’; in another entry he is given as a ‘Surveyor’.

Sydney Herbert Allard was tall and sturdy. As well as wearing horn-rimmed spectacles, he had a damaged right eye as a result of a boyhood injury sustained by an airgun pellet fired in a mock fight by his brother Dennis. Yet the eye problem never seemed to affect his abilities and Sydney was undoubtedly a talented driver. This was the era of shirt-sleeved drivers and no seat belts. On several occasions in later years Sydney was even seen racing in a sports jacket and tie, but he was not a toff, a playboy or, in any sense, a man ‘on the make’. He simply thought about cars, drew cars, chopped up cars and welded them back together again until one day he created a car of his own conception. From there came the brand.

Sydney’s brothers were avid motorcycle enthusiasts who shared the family’s wheeled obsession. William Boddy, Editor of Motor Sport, who was a big Allard fan, described Sydney and his brothers as ‘pretty wild, even as youngsters go’. Dennis Allard, who had survived a major accident on his Brough Superior when he was just 21, was sadly killed in a cycling accident on his way to the Brighton Speed Trial in the 1950s. His twin, Leslie, would have an interest in both two- and four-wheeled devices.

The first four-wheeled car was a one-off ‘special’ modified Morgan. It was emphatically not a fully fledged ‘Allard Special’. Sydney carried out extensive work on his Morgan to convert it from three wheels to four in a vain attempt to make it more suitable for trialling.

Sydney’s boyhood was surrounded by younger brothers who fettled and tweaked their motorcycles. Sydney learned to ride on a Francis-Barnett and moved on to a Douglas with a flat-twin engine. He learned to drive at the age of 16, soon after leaving Ardingly College. He decided not to join the family building business, and instead started work in a garage, F.W. Lucas. Evening courses in engineering at Battersea Polytechnic enabled him to become accredited with the Institute of Engineers. Beginning as a fitters mate, earning a few shillings a week, Sydney worked his way up through hands-on experience as a mechanical engineer. Admittedly there was family money and a good education behind him, but his father was not keen on his son’s sporting aspirations in the risky new world of cars. Sydney was soon an active member of local car and motorcycle clubs.

All the members of the family enjoyed motorcycle trips and days out in the family Ford, frequently to Sussex. This was where Sydney’s ‘Clubman’ and ‘Trials’ driving experiences began. Jack’s belt-driven Douglas motorcycle was handed down to Sydney and this gave him his first taste of fiddling with greasy mechanical devices that needed servicing and repairing. A Morgan three-wheeler that had been tweaked in various ways by the brothers was also handed down by Jack.

Arthur Allard soon accepted that his second son was not going to join the family building firm, but it was clearly a father’s duty to provide guidance and support. This was manifested when Arthur bought his way into a business and then encouraged the young Sydney as he turned it into a viable motor business. His son’s developing love of things wheeled and noisy was funded and controlled by an older and wiser business partner, Alf Brisco (spelled without an ‘e’, according to the Adlards Motor Company letterhead). Hard graft was required, but Sydney also relied on his father’s helping hand. The small garage that sowed the seed of Allardism was located in Keswick Road, Putney. By a strange coincidence, the trading name of the business purchased for Sydney was R. Adlard. This was soon rejigged as the trading entity Adlards Motors, and the unintended similarity of the owner and company name was to cause some later confusion. The Allard family eventually lived almost ‘over the shop’ in a block of flats with roof gardens and views over London that Arthur Allard had built on the site of the original Adlards premises, with its garage on the ground floor.

Sydney repaired, modified and sold cars from the Adlards garage under the tutelage of Mr Brisco. The new enterprise was a Limited Company and the named officials were Sydney, Alfred Brisco and, curiously, Sydney’s mother Cecilia. The Adlards Motor Company was officially inaugurated on 5 April 1930. Two important events that took place by 1934 were the appointment of Reginald ‘Reg’ Canham to the company and the award of a dealership franchise by the Ford Motor Company of England. The financial security and personal confidence that this brought enabled Sydney to undertake a flourishing amateur career away from the garage, where he could store his various mechanical projects and hope that his father did not ask too many questions. Not yet twenty-five, the essential construct of Sydney’s personality and direction was now set. His early interest in mechanical devices had been concentrated on motocycles. When he was twelve years old, for example, he was interested in Francis-Barnett motorcycles and the family still has a scrapbook full of cuttings about them.

The Streatham and District Motorcycle Club was also important on the local scene. Cars were also popular in this part of south London and Sydney was immersed in a world of emerging wheeled opportunity in a new age of growing mass motoring.

Bill Boddy later claimed that it was he who persuaded Sydney to form the Ford Enthusiasts Club in 1938. After the war he was a passenger when an Allard driven by Sydney turned over, but fortunately he was thrown clear. Boddy lived until he was 98 and was much loved by the Allard Owners Club.

Sydney was not an egotistical extrovert, but he was a confident speaker who enjoyed social gatherings and often gave talks to motor clubs and other groups in later years. His sister Mary, who served as Company Secretary for his ventures, recently told the Allard Owners Club that she thought Sydney was the one of the brothers who ‘tried to be in charge’, and that he ‘had a great deal of charm and people liked him, helped him’. Because of that he could ‘get around anybody. Even if people did not like him in business, they thought he was a damn good bloke! Everything came easy to him. Everyone rushed to help Sydney.’

Mary’s first husband was Eddie McDowell, who worked for Allards as purchasing manager. Three years after his untimely death she remarried Sydney’s brother in-law Alan May in 1959. Prior to that Mary had been closely involved in running Allards, including organizing Sydney’s vital trip to New York to set up the Allard Motor Company Inc., New York (USA).

Her nephew Darell described Mary as an outspoken character in his 2017 published tribute to her:

She did not always agree with anecdotes I heard from other members of the family, mainly my father Leslie. Even at the age of 94, when I showed her a photo of a P1, which Sydney was known to have driven, parked outside Dralda House in Putney, I was told in no uncertain terms that this was ‘her car’, which he used to ‘borrow’!

Mary clearly contributed to the day-to-day running of Allard and dealt with payments, supplies, orders and all sorts of company affairs. It must have been interesting to see the interaction between Mary and Sydney, two strong characters. Sydney was a driven personality who inspired other people to work for him, backed by Allard family money.

Sydney’s training in mechanical matters and formal engineering studies show he was not an amateur who stumbled upon his cars’ form and function through step-by-step ‘episodes’, but we can say that he used his experiments to create a range of curiously diverse cars. Some of Allard’s later issues, particularly the diverse model range in the 1950s, which was expensive to manufacture, and Sydney’s inability to develop his car designs without being sidetracked, may have been down to this working method.

The roots of Sydney’s production cars lay in his early 1930s ‘Allard Specials’ designed to compete in Trials events, which were a popular combination at that time of road, rally and off-road trialling exploits. Elements of these were combined with their predecessor, Sydney’s Morgan three-wheeler, modified to take a fourth wheel and hand built with revised mechanicals and suspension. Based on his early experiment with the Morgan, Sydney built a Ford ‘flat-head’ side-valve V8-powered Special, giving a high power-to-weight ratio with consequent rapid acceleration, and swathed in an aluminium body. Allard’s Trials cars were relatively low-geared, high-powered and rear-driven, resulting in the ‘Tailwagger’ team sobriquet, since the oversteering rear ends were renowned for swinging out on mud and gravel, and being caught with armfuls of opposite lock.

During the Second World War Adlards Motors was turned over to repairing military vehicles, but within a year of the end of hostilities Sydney Allard was a carmaker, an option he had been thinking about for some time. Uniquely, Allard was ahead of the social curve since in many ways his thoughts and marketing were a decade ahead of the times. The imminent breaking down of social and class barriers was in one sense reflected by the motor industry in the rise of classless design and new money to pay for exotic or powerful cars, both ‘Specials’ and post-war sportsters.

Yet Allard’s true, car-creating roots lay in the Specials he produced in the heady pre-war days. Eleven of these were built at that time, plus one after 1939. It was these designs that coalesced into the first Allard roadsters of 1946.

Allard’s competition cars relied little on seat belts, roll cages, fire-eater systems or bodywork protection. Only the strength of the underpinning chassis and metal shell offered safety. The bespectacled Sydney, only sometimes wearing a hard hat and doing without a seat belt or roll-cage, would win event after event, while running his company at the same time. He darted about all over the place to compete in events on an almost inconceivable schedule. In a single month he would think nothing of competing in Italy, France, Jersey, the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, often driving to and from the events in his race car. On other occasions the competition cars were transported in the Allard team transporter by Jim McCallan, Tom Lush or others. Week in and weekend out Sydney would compete in races at Goodwood, Silverstone, Shelsley Walsh, Prescott, Bo’ness and at various regional Trials. He kept overalls and personal cleaning kit in his office just in case he was needed down on the factory floor to do some manual labour. The works and competition schedule was hectic and fatiguing, and his workaholic behaviour and high stress levels may have contributed to the stomach cancer that eventually killed him at the early age of 56.

Allard was a brave man in an age when death was commonplace in motor sport. He survived a horrific, mass pile-up on the Isle of Man in the Empire Trophy in 1951, and it was only by chance that both Sydney and his wife Eleanor escaped a major roll-over crash. Many commentators remarked on Sydney’s personal bravery and wondered how he had avoided being badly injured or killed in a series of off-road excursions, including several dramatic escapes in Europe. His co-driver Tom Lush was quite open about the nature of Sydney’s driving style: determined, fast and, it seems, occasionally a bit furious.3

ALLARD & CO

Intriguingly, Allard as we know it was the second British carmaker called Allard. The unrelated Allard & Co started production of motorized tricycles of a distinctly ‘Benz’ design in Coventry in 1899. The company also produced an air-cooled 3hp car. By 1902 this short-lived early ‘Allard’ company had merged with the Rex Company, which was itself extinct by 1914. There is no link between the Coventry company and Sydney’s.

THE ETHOS OF ALLARD

Allard cars are unsung heroes of an age long gone. What was their magic ingredient? What, how and why did Allards develop an ethos and a style, a brand and a marque that was world famous for a few years before fading into a motoring footnote?

Sydney Allard was not a motor-industry boss somehow intent on mass production, neither was he looking for celebrity stardom. He was interested in opportunities to race, rally and make the most of any circumstance, rather than pursuing some grand plan to build and sell cars and carve a niche. This was carried out with a focused dedication lightened by a strong sense of humour that came to the fore in his relationships with his family and factory team members. While approachable, he was also ‘the boss’ and it seems he could be forceful and dominant, which should hardly be a surprise in one who achieved so much with so little.

In 1936 Sydney married Eleanor May, whose family’s principal business was repairing and restoring Rolls-Royce cars from large premises in south London. Eleanor later drove Allard cars in competitive events. Eleanor’s brothers, Norman and Alan May, owned Southern Motors in Park Hill, Clapham, which later became the head offices of the Allard Motor Company. Alan May drove a very powerful Vauxhall 30/98 in which he beat Stirling Moss at the Brighton Speed Trials in 1948 and in the following year he was Sydney’s co-driver in the 1949 Monte Carlo Rally in an M Type.

The record shows that Sydney Allard was a competitive driver with a winning record in British championships and major events. He was rarely off the podium and was a pure enthusiast who knew about powerful and ‘hairy’ rear-driven cars, such as his very fast modified V8s. This required a determined streak, but he also needed to keep making money. Fortunes could be lost very quickly in car racing in the 1950s, let alone in low-volume design and production. In fact, seemingly a touch obsessed with competition driving, Sydney employed salesmen and engineers to get on with creating and marketing the cars, led in the 1950s by H.J.A. ‘Dave’ Davis.

The marketing driving force behind Alllard was co-director Reg Canham and a close-knit group that helped Sydney build and frame his brand. It was Tom Cole in America who first suggested, in March and April 1950, fitting the recently announced Cadillac V8 to an Allard, although a vital paper trail of evidence indicates that a customer, Frederick Gibbs, seems to have come up with the same idea almost simultaneously.

It took a long list of names to help develop Allard from its roots, based on the garage and premises of the confusingly named Adlards Motors. The many members of the Allard staff team whose deeds are described here included Reg Canham, Tom Lush, Jim McCallan, Eddie McDowell, Jimmy Minnion, Dave Davis, Jack Jackman, Sam Whittingham, Bill Tylee, David Hooper and Dudley Hume.

The notion that Sydney was not bothered by the need for publicity is disproved by his appointment of Jack. R. Bullen as a resident Allard Publicity Manager in 1949, based at the 24/28 Clapham High Street offices. Sydney outlined the company’s intentions in a 1952 statement: ‘The aims of the Allard Motor Company are, as they have always been, to produce high-performance cars and to sell them at the lowest possible price consistent with limited and specialist production.’

These cars were not exclusive exotica for the raffish boulevard poseur, but ‘proper’ sports cars cast entirely in their own mould. Many of the cars, however, were more tourer than two-seat racer. They employed both off-the-shelf parts, mostly of Ford provenance, and bespoke items, but everything was brought together to meet a formula defined by Sydney. This was well before the rise of Healey as a British sporting marque of distinct identity. Sydney Allard knew that a product defines a brand, not the other way around. His cars were therefore the measure by which he wished to be judged. Perhaps only the British Railton Company, which used Hudson-derived parts in their 1930s sports cars, could be cited as similar to the Allard approach. Other cars contemporary with Allard’s early era included the supercharged Vauxhall Villiers, based on a 1920s TT chassis that was drastically modified by Raymond Mays and Amherst Villiers, just as Allard would do with his cars.

Sydney Allard said that his competition cars were ‘tailored’. This was true, but it might also be a euphemism for every car being different according to what parts were on the shelf! This, to some degree, also applied to his road cars. The story of the Allard car began in somewhat curious circumstances. There were no known engineering or mechanical antecedents in Sydney’s story, but Sydney and his brothers were born into an age that may be viewed as the late dawn of the motorcar and motor sport.

FIRST THOUGHTS, 1910–30

From early boyhood Sydney Allard was an engineering enthusiast. He was modifying cars to incorporate his own engineering ideas before his twenty-fifth birthday, and it was not long before he created new configurations using other manufacturers’ parts.

He chronicled his early interest in a scrapbook of car reports, tests, brochures and information that spanned cycle cars, light cars and big beasts. This information fed his mind and his own car design ideas expressed in early sketches and specifications that showed he was thinking of cars in a serious vein, not just a hobby. These led to his first modifications to existing cars and then the true, home-built ‘Specials’ from 1936. We should not forget that Sydney won his first competitive entry on the banked outer circuit at Brooklands in 1929 in a Morgan.

Special sketches from Sydney’s personal sketchbook. Unpublished and unseen for decades, these design ideas from Sydney’s pen show just how busy his brain was, always thinking of the next project. Styling, airflow and marketing are all obvious ingredients that challenge any ideas that Sydney was not interested in such matters.

Sydney Allard did not have an automotive inheritance and had access to few engineering, design, styling or testing resources, but he managed to break into a world that would soon be littered with names like AC, Aston Martin, Frazer Nash, Riley, MG and even the emergent Jaguar. The story of how a very determined man took on and defeated such established names with far greater resources is one of astounding achievement that can be followed in detail because he kept all his studies, and these have been preserved by the Allard family.

Sydney Allard did not dream of selling out to a major motor manufacturer or have any delusions about a ‘celebrity’ lifestyle. The family are certain that he knew who he was and that’s the way he stayed. Indeed, as Sydney often stated, he choose his employees for their enthusiasm and loyalty. He did not have a Board stuffed with directors or need to satisfy the demands of shareholders relying on vast profits made at the workers’ expense: ‘As a family concern, we have no necessity to constantly aim at increased turnover and profits in order to satisfy shareholders whose natural interest is dividends rather than motorcars.’4

Sydney was instrumental in the development of British motor sport. He became Chairman of the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC) and was a key figure in the creation of the Thruxton circuit from its origins as an airfield: a bend there is named ‘Allard’ in recognition of his work. His fame at Prescott hill climb was also significant and is marked by a particular point on the hill being known as ‘Allards Gap’. Sydney was ‘the guvnor’ to those that knew him well, but he built up a close-knit team of trusted people to run both the business and competitive activities. One who stands out from these is Tom Lush, who was alongside Sydney in many of his exploits. Lush seems to have been able to perform a variety of multi-disciplinary roles and served as Sydney’s right-hand man from 1946 to 1966, providing a detailed diary of these events in his book Allard: The Inside Story.

Everyone has to start somewhere, however, and Sydney’s achievements began with his ‘Clubman’ years.

THE CLUBMAN YEARS: THE GENESIS OF ALLARDISM

We are fortunate that Sydney recalled his start in competitive car racing at club level in his unpublished My Life as a Clubman:

I suppose I can truthfully talk about life as a Clubman, as I joined my first club for motorcyclists in 1928, and entered my first trial that same year. I was a proud owner of a Morgan three-wheeler and I entered it in the Trial which was to be held in the West Country. Starting at midnight, on the way down I soon found that the combination of low ground clearance and plenty of wheel travel from the single rear wheel was not the right recipe for covering a motorcycle trials course on Dartmoor.

However, I got a medal, my first motoring award. I am still a member of that Club, Streatham and District Motorcycle Club. Incidentally, one of the members used to bring his sisters with him and one of them was Eleanor, now my wife.

I ran the Morgan for about four years, and most of my activities were centred around the various motorcycle clubs including the British Motorcycle Racing Club, whose headquarters were at Brooklands circuit.5

Sydney goes on to describe how, despite successes with the Morgan, notably at Brooklands, he was up against cars like Rileys, Salmsons and Amilcars, all nimble little lightweight things derived from ‘cyclecar’ or light car origins. Despite being capable of an 80mph lap at Brooklands in standard tune, and more than 90mph once he had tweaked it (records indicate a handicap lap time of more than 100mph in a fifteen-lap race), the three-wheeler Morgan was soon found to lack the stability at high-speed essential on the Brooklands banking and adequate ground clearance; good ground clearance was soon to be a key factor in Allard cars. According to Sydney, ‘I eventually decided that the Morgan was not quite suitable for this sort of Trials event’.

This was the moment when the need for a four-wheeled car with higher ground clearance and better handling became defined in Sydney’s mind. More power and torque was needed. Sydney could not ignore the hill-climb and racing success of the supercharged Villiers-tuned Vauxhall TT and the twin-supercharged, chain-drive Frazer Nash ‘Shelsley’ types. One of the Frazer Nash cars was actually campaigned by Margaret Allan, who achieved her ‘Brooklands 120mph’ badge in a Bentley. The early Anzani-engined Frazer Nash cars of 1928–30 gave way to a Meadows powerplant in the 1930s (supercharged to 18psi boost), which could provide hill-climb drivers with a massive wall of urgent and short-lived torque, but its reliability was bound to be problematic when exposed to long-distance, high-speed race running. By 1936 Frazer Nash would use straight-six BMW engines. As with other competition cars of these years, there was a trade-off between hill-climb power that would last for about five minutes or racing endurance to last several hours at lower revs. The key factor was engine weight versus component strength and reliability. Such issues were all relevant to Sydney Allard’s thoughts on building his own ‘Specials’ to perform similar tasks.