Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

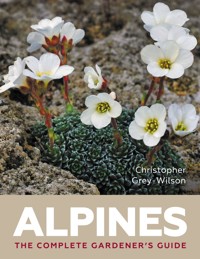

Hailing from the world's harshest climates, the iconic edelweiss, vibrant blue forget-me-nots, delicate saxifrages, and stunning gentians are just a few of the exciting species that you will discover in this book. Short detailed descriptions and images reveal the intricate world of more than 400 species and cultivars, providing an informative and practical overview of cultivating alpines whatever the size of your garden or patio. Written for the gardener, enthusiast and horticulturist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 636

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A colony of Primula russeola inhabiting an open stony meadow on the Guzza La, Bomi, SE Tibet. (Photo: Harry Jans)

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: What is an Alpine?

Chapter 2: Alpines in the Garden

Chapter 3: Alpine Plant A–Z Directory

Chapter 4: Annuals and Biennials A–Z Directory

Chapter 5: Hardy Succulents A–Z Directory

Chapter 6: Small Shrubs A–Z Directory

Chapter 7: Bulbs A–Z Directory

Appendix: Alpines for Different Situations in the Garden

Glossary

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

Alpine plants are amongst the most beautiful and colourful of any group of plants that we grow in our gardens. It is difficult to believe that these fascinating little plants are native to some of the highest, most remote and harshest regions of the world. Even more surprising is the fact that so many can be adapted to grow in our gardens. Like any group of plants, studying their growing conditions in the wild can tell us a great deal about how to cultivate them successfully.

There are many saxifrage species in mountain regions including various forms of Saxifraga oppositifolia, the purple saxifrage, widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, including northern Britain.

Alpines are intriguing plants that add a great deal of interest to the garden, and many are easy-to-grow, adaptable plants well suited to today’s smaller gardens. Many garden centres have an area devoted to alpine plants, the more innovative putting on small displays showing different ways in which they can be grown and shown. In addition, specialist nurseries stock a wide range of alpine plants. Today there is a renewed interest in alpines as with careful selection, alpines can provide interest and colour throughout the year and few plants can rival the intense blue of a trumpet gentian in full flower, the silky softness of a yellow or purple pasque-flower or the delicate nodding bells of one of the alpine harebells borne on the thinnest of stalks.

Alpines used to be considered connoisseurs’ plants, and many cushion types from high altitudes were believed impossible to grow unless you were an expert, but this is not so. Today alpines are considered in the broad sense to include a vast range of plants from mountain regions around the world including many from high alpine habitats, small shrubs, many small herbaceous plants, small hardy bulbs, hardy terrestrial orchids and ferns, a plethora of exciting possibilities. That is why some gardeners prefer to describe them as rock plants rather than alpines.

Although cushion-forming alpines are considered amongst the more difficult to grow successfully, there are quite a few alpines that are easy to grow in the open garden without the need of an alpine house or frame. Nor is it necessary to build expensive rock gardens to grow them successfully. A carefully planted trough or container can house a surprising number of these little gems and become a real feature in the garden.

The prime purpose of this book is to celebrate the virtues and diversity of alpine or rock garden plants. There are far too many to include in a single volume, so a selection has been made. Several factors came into play. First, the plants described had to be widely available from garden centres or nurseries or through one of several alpine societies and clubs. Second, on the whole, they had to be relatively easy to grow provided certain cultivation requirements are adhered to, especially position in the garden and soil composition. Third, with careful selection, they need to provide interest throughout the year.

I have included one or two rarer and more difficult alpines, such as the beautiful Jankaea endemic to Mt Olympus in Greece, or the startlingly beautiful Asian paraquilegias, as they are hard to resist. They do, however, reveal the great diversity and beauty of this fabulous group of plants.

Certain groups of alpines are of prime importance to the alpine gardener. Of special significance are the bellflowers (Campanula), gentians (Gentiana), primulas (Primula), saxifrages (Saxifraga), violets and pansies (Viola), all large groups with a significant number of species in cultivation, but just as important are the many hybrids within each that have been raised in cultivation, the majority distinguished with distinctive cultivar names.

Gentiana acaulis, the spectacular trumpet gentian, at home in the Alps and Pyrenees.

Pulsatilla grandis ‘Budapest Blue’, derived from seed originally collected in the hills near Budapest in Hungary, is one of the most sought-after alpines.

Aquilegia alpina, one of the finest and brightest blue alpines, is native to the Alps and Apennines.

Corydalis flexuosa, here ‘China Blue’, was first introduced from western China in the latter half of the last century and is now widely available.

A harebell, Campanula chamissonis, is found in the wild in remote parts of Japan, the Aleutian Islands and Alaska but, despite this, is an accommodating garden plant.

The glacier buttercup, Ranunculus glacialis, is a denizen of high, often rather bleak habitats, here photographed in the Hautes-Alpes. The flowers become pink with age.

Some beautiful alpines can only be seen in the wild and have proved extremely difficult to grow successfully in cultivation. These include two Patagonian species, Gentianella hirculus (left) and Swertia lugardii (right) – both members of the gentian family. (Photos: Robert Rolfe [top] and Harry Jans [bottom])

Bulbs feature very highly among alpine gardeners’ favourites and in recent years dog’s-tooth violets, here Erythronium hendersonii, have become a focus of attention.

The iconic Jankaea heldreichii, a relation of the African violet, is endemic to the cliffs and rocks of Mt Olympus in Greece.

CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS AN ALPINE?

Spectacular mountain scenery, panoramas of distant ridges and peaks, this is the home of numerous alpine plants around the world. The often rugged and harsh terrain provides many different habitats to which these specialised plants have evolved.

A mountain meadow dominated by Trollius ranunculinus, a member of the buttercup family, near Jigzhi in eastern Qinghai province, China.

In the strict botanical sense, alpine plants are those that grow above the tree-line in mountains around the world, whether that is in Arctic, temperate or tropical regions. The tree-line is not at a fixed altitude: generally speaking, the tree-line is lower the further north or south away from the equator you travel and in some extremely northerly or southerly latitudes it may be close to sea level. In addition, in the Northern Hemisphere, the tree-line is usually higher up a particular range of mountains on the south side than it is on the north, or vice versa in the Southern Hemisphere.

For gardeners, as opposed to botanists, alpine plants encompass any small hardy plants that can be grown on a rock garden, including many adaptable and colourful species from close to sea level, even from the Mediterranean-type climate regions of the world.

The Himalaya have attracted plant lovers over many years, the remote and often hazardous terrain home to many exciting alpine plants. A view of Annapurna Sanctuary in central Nepal.

The French Alps; Col du Galibier with Ranunculus glacialis in the foreground.

Pulsatilla alpina subsp. cattaniae in the Savoie Alps of eastern France, where grassy slopes give way to screes and snowy ridges.

Lush colourful meadows, here with globeflowers, Trollius europaeus, in the Haute-Savoie, belie the harsh conditions of the steep snowy peaks close by.

Central Afghanistan in dominated by the western Hindu Kush, today a forbidden territory to most foreigners, but in the latter half of the last century a focal point for exploration by botanists and biologists. Photo taken above Band-i-Amir, west of Bamian.

Snowbound for months during the winter, the Col du Galibier in the Savoie Alps comes alive in the spring, with many colourful alpines, including the brilliant blue Gentiana schleicheri.

Northern Spain is dominated by the Cantabrian Mountains; the Picos de Europa is an area of outstanding natural beauty with a wealth of interesting alpine plants.

Primula thearosa photographed on a steep mountain slope on the Galung La, Bomi in SE Tibet (Xizang). (Photo: Harry Jans)

The extraordinarily highly insulated elongating leaf-rosettes of Saussurea medusa give protection from the harsh montane conditions at high altitude, as here on the Balangshan in W Sichuan, China. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Rocky slopes and the upper tree-line on the slopes of Mt Rainier, in the American Cascades, Washington Province, USA.

The extraordinary vegetable sheep of New Zealand belong to two genera, Haastia and Raoulia; here Raoulia mammillaris nestles close by a cliff on Mt Hutt, South Island.

Weather-blasted white pines, Pinus albicaulis, mark the tree-line on the slopes of Mt Hood (Oregon) in the American Cascades, with Mt Rainier, another volcano in the background.

The attractive garden-worthy Eriophyllum lanatum, photographed on Mt Townsend, Washington State in the extreme NE of the USA, has become more readily available to gardeners in recent years.

Certain local conditions may allow true alpine plants to descend to much lower altitudes than is the norm. For instance, the lovely and well-known spring gentian, Gentiana verna, is a widespread alpine in the European mountains but it is also native to the limestone pavement area of the Burren on the west coast of Ireland. In addition, several alpines found high in the Alps or Pyrenees can be found in the Arctic region, in Svalbard for instance, growing at very low altitudes, even close to sea level.

Botanical details

Most people think of alpines as small, neat and colourful plants, often with large flowers for the size of the plant and this is true of many of those grown in gardens. But true alpine also encompasses some quite large plants, the so-called mega-alpines. The giant lobelias (Lobelia keniensis and L. telekii for instance) of the East African mountains, which can attain 2–3 metres in height at flowering, and the giant rhubarb, Rheum nobile, from the Himalaya, which can be just as tall, are fine examples. However, most true alpines are small and often discreet. They have adapted over thousands of years to the harsh environment of high altitudes in various ways, taking on several characteristic forms.

The conditions at altitude include:

• Warm or sometimes hot summers with a short growing season, the dry periods often interrupted by thunderstorms. This is true of many of the European mountains. In contrast, in the Himalayas and the mountains of western China and south-eastern Asia, although the winters can be extremely harsh, the summers, when many of the plants are in full growth, can be very wet, influenced by the extended monsoon period. In these regions, the dry seasons are in the spring and early autumn.

• Long, cold winters; plants often survive under snow for long periods. In most mountain regions, snow and ice cover large areas for much of the year. The streams and rivers freeze over for weeks, sometimes for months on end. During this period a huge range of different alpine plants can survive, rushing into growth the moment spring arrives.

• High levels of ultraviolet (UV) light. This is particularly relevant to alpine plants and all the animals, insects and other creatures that inhabit the alpine landscapes around the world. Flower colours look brilliant at altitude, a brilliance that can be readily captured by modern digital cameras. The display of bright colours in spring and summer is one reason many nature lovers are attracted to the mountains and why walking in these wild areas can be so rewarding.

• Windy and exposed positions. Many alpines grow in very exposed positions, sheltering amongst rocks, in cliff crevices, in hollows or protected by neighbouring plants. At times fierce winds blow across the mountains: one element in the evolution of the low and compact forms of many alpine plants.

One interesting fact is that even at the highest altitudes where alpine plants are found (over 20,000ft/ca.7,000m) beetles, flies, bees and butterflies are to be seen. The showy flowers of many alpines attract pollinating insects and ensure eventual fertilisation in the majority of plant species found at altitude.

Types of alpine

Alpines have adapted to mountain environments around the world, yet the same forms have evolved repeatedly to cope with the harsh conditions of their habitat. Exposure, wind and terrain are dominant factors, as are rock type and precipitation (rain and snow). Conditions at low altitudes, especially in coastal regions, can be just as harsh – which is why some plants from these places are classed among ‘alpines’ by gardeners.

Dwarf shrubs

Above the tree-line small shrubs and shrub communities often form patches, some extensive on mountainsides. In northern temperate regions, dwarf willows, low rhododendrons and numerous other small deciduous or evergreen shrubs form entanglements that can harbour and protect other plants. Plant communities in the Southern Hemisphere follow similar patterns but with generally different associations of species.

Rhododendron caucasicum nestling between boulders in the Georgian Caucasus, near Kazbegi. There are numerous small rhododendron species for the alpine gardener to enjoy, especially from the Himalaya and Western China.

Polygala chamaebuxus (here the yellow and white version) is essentially a dwarf creeping shrub or shrublet.

Ribes laurifolium adds interest to the spring border, a low slow-spreading evergreen shrub from Western China. This is the cultivar ‘Amy Doncaster’.

Genista pilosa, one of the finest rock garden shrubs; ‘Procumbens’ is low and matted, slow-growing and very floriferous.

Cushion alpines

Perhaps the most well-known alpine form is the cushion, present in many, often unrelated, alpines. It is a form which can be found in most mountain regions and also in harsh environments at low altitudes, especially rocky coastal areas. Cushions usually consist of tightly congested growth, each shoot terminating in a small, often tiny rosette of leaves. The cushions can be low hummocks or domed and the flowers may be borne immediately on top of the cushion or on stalks above the cushion. Many alpines grown in the alpine garden are of the cushion types. Numerous saxifrages, the dionysias, sandworts (Arenaria) and the rock jasmines (Androsace) belong here. Moss campion, Silene acaulis, is a fine example of an alpine cushion forming a tight dome of tiny bright green leaves smothered in spring by vibrant little pink flowers.

Another dwarf sub-shrub, Haplopappus glutinosus from Argentina and Chile, makes a bold display of daisies in early summer.

Daphne is the supreme alpine garden shrub and there are many species and cultivars from which to choose. ‘Anton Fahndrich’ is compact, evergreen and a profuse flowerer once established.

Arenaria polytrichoides, a classic high-altitude alpine from the mountains of the Himalaya and Western China, can make substantial cushions up to 100cm across.

Chionocharis hookeri, devilishly difficult to cultivate, is one of many cushion alpines from the Himalaya and Western China (photographed on the Baimashan, Yunnan), and is a close relation of the garden forget-me-not. (Photo: Harry Jans)

The delightful Androsace alpina, a native of the European Alps, forms small cushions, often growing amongst rocky detritus. (Photo: Peter Erskine)

The majority of species of Dionysia are cushion-forming cliff-dwellers. D. tapetodes, photographed in eastern Afghanistan, is often seen in cultivation amongst specialist growers.

A perfect cushion of the European Minuartia recurva photographed in the Transylvanian Alps, Romania.

Campanula andrewsii on seaside rocks by Monemvasia in the Greek Peloponnese, forms symmetrical domes. It is a good example of a lowland cushion accepted into the alpine gardeners’ ‘alpines’.

Campanula bellidifolia, photographed in the Georgian Caucasus, close to Kazbegi, one of a number of beautiful cushion-forming bellflowers from the region.

Silene acaulis, the moss campion, widespread in the mountains of the Northern Hemisphere, can form discreet cushions or broader mats in the wild.

A first-rate lax, cushion-forming alpine, Aethionema × warleyensis ‘Warley Rose’, an excellent starter alpine for growers.

Mats

Ground-hugging mats are a common adaptation evolved for many alpines, especially those growing in very exposed positions in the mountains at many different altitudinal levels. The mat form has evolved in many familiar genera such as some species of rock jasmines (Androsace), gentians (Gentiana), saxifrages (Saxifraga), speedwells (Veronica) and thymes (Thymus), and includes some dwarf shrubs like willows (Salix reticulata and S. retusa, for instance).

Globularia cordifolia, an evergreen matted subshrub, forms perfect slow-growing mats. Photographed in the French Alps.

Veronica umbrosa ‘Georgia Blue’ is a popular and widely available speedwell originally hailing from the Caucasus Mountains. It forms lax spreading mats flowering over a long season.

The Turkish Teucrium ackermannii forms mounded mats to 100cm across, sometimes more. Flowering in early summer, it is great for attracting bees and butterflies into the garden.

Mountain avens, Dryas octopetala, a matted subshrub found in the mountains of the Northern Hemisphere, including Arctic regions.

The small fairies’ thimble, Campanula cochlearifolia, forms spreading mats by means of slender underground stolons. A great delight, it is found in many shades of blue and lavender, occasionally pure white.

Herbaceous perennials

Quite a few alpines from a diverse range of habitats are classed as herbaceous perennials. Just like the large perennials of the herbaceous border, these are smaller, lower-growing plants that die down annually to a resistant over-wintering stock. These perennials take on various forms from tussocks to mounds or mats. Many large herbaceous garden plants have their alpine equivalents. There are herbaceous alpine species of familiar genera including Achillea, Anemone and related Pulsatilla (the pasque-flowers), Aquilegia, Primula (not all species), Salvia and Silene. There are numerous others that fit this category.

Easy and popular, Alchemilla mollis adds interest to the garden from early spring to the autumn.

Anemonella thalictroides flowers in the spring and, like most herbaceous perennials, dies down in the autumn to overwinter at ground level.

The common pasque-flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris, is a typical small herbaceous perennial, delighting in the spring with its anemone-like blooms in a variety of colours, typically purple, lavender, pink, red or white.

Aster alpinus, widespread in the European mountains, has daisy heads typically in blue or lavender, but other colours are available in cultivation.

Campanula glomerata, the clustered harebell, an easy and reliable alpine forming patches in the rock garden, but also suitable for the front of the flower border.

A graceful North American woodlander, Uvularia perfoliata, will thrive in cooler parts of the alpine garden.

Rosetted alpines

Another interesting form, one that is not unique to alpine regions by any means, are alpines that make a large leafy rosette. In some, there is just a single rosette, while in others the plants build up a tuft or mound of rosettes in time. Ramondas are of the latter type. Certain genera such as Primula and Celmisia contain numerous species with basal leaf-rosettes. In some species of blue poppy, Meconopsis, the solitary leaf-rosettes take several years to increase in size before sending up a stem and flowers. These monocarpic species die after seeding and the whole process has to start all over again. This, of course, means that gardeners have to be diligent and collect seed on a regular basis to ensure continuation in the garden.

Primula latifolia, from the Alps, is typical of numerous species within the genus, producing scapose flowers in small terminal clusters.

Celmisia, primarily New Zealand in origin, has mainly white daisy flowerheads and basal leaf-rosettes. C. semicordata has bold rosettes with spear-like leaves.

The North American genus Lewisia is noted for its basal rosettes of rather fleshy leaves and eye-catching displays of flowers; L. rediviva, popular amongst alpine growers, is widespread in the mountains of western North America.

Saxifraga ‘Southside Seedling’, a fine example of a rosetted alpine, with a basal cluster of several leaf-rosettes, with individual rosettes dying after flowering, to be replaced by fresh rosettes.

The trumpet gentian, Gentiana acaulis, produces a close clump of leathery leaf-rosettes and spectacular solitary flowers.

The poppy-like species of Meconopsis are noted for their basal leaf-rosettes, which range from small and tufted to large and handsome. M. horridula is a high montane species from the Himalaya and Tibet (Xizang). Like Saxifraga longifolia the species has a monocarpic habit, dying after flowering and fruiting.

Succulent alpines

These include alpine cacti from the American mountains, but different genera of succulent plants with small or large, thick and fleshy leaves are found in many mountain regions. In Europe and Western Asia, stonecrops (Sedum) and houseleeks (Sempervivum) are prime examples; in Southern Africa the genus Delosperma and its close relatives are plants adapted to hot, dry, rocky, extremely well-drained habitats. Succulent alpines fit in extremely well with those gardeners wishing to plan for hotter and drier gardens as global warming increasingly becomes an issue, especially in temperate regions.

Roseroot, Rhodiola rosea, forms succulent mounds. A denizen of rock places in the wild, it is a classic rock garden plant.

Popular in today’s smaller garden and requiring little attention, houseleeks, Sempervivum, are succulent, rosette-forming alpines, available in a multitude of sizes and colours, many with fancy cultivar names.

Sedum kamtschaticum forms dinner-plate mats of slow-spreading succulent shoots that are enhanced in summer by masses of little starry yellow flowers.

Annual alpines

The annual habit, whereby a plant completes its entire life cycle in a single year, is quite rare in most mountain regions, primarily because the growing season is so short. There simply is not enough time to complete the annual cycle. Some alpines are biennials, completing their life cycles in two seasons, but these are also quite unusual in the high montane region of the world. Most annuals and biennials recommended for the alpine garden are in fact lowland or low-montane plants.

Limnanthes douglasii, the so-called poached-egg plant, hails from the Western USA, an over-wintering annual producing a mass of yellow or white flowers in the spring, later if spring-sown.

Omphalodes linifolia, a relation of the forget-me-nots, is a charming annual from Spain and North Africa, highly satisfactory in pockets of the rock garden. Excess seedlings are easily removed.

Bulbs

Here is included all plants with an underground storage organ, bulb, corm, tuber or thick rhizome. They are all storage units that reside below ground during unfavourable seasons of the year but, when the conditions are right in the spring and early summer, the plants appear quickly above ground. Crocuses are prime examples popping up in the spring, sometimes in very large numbers, the moment the weather begins to warm and the snow melts. Several families dominate, particularly the daffodil family, the lily family, and the iris family. Other significant genera include Chionodoxa, Corydalis, Galanthus, Fritillaria, Scilla and Tulipa. While many are spring flowering, others put on a display in the summer and autumn.

Narcissi, like Narcissus ‘Bowles Early Sulphur’, make ideal companions to the early spring border.

Dog’s-tooth violets, Erythronium, have become increasingly popular in recent years with numbers of new hybrids and selections being named, here an old favourite E. californicum ‘White Beauty’.

Fritillaria meleagris, a British native, is a plant of damp meadows, thriving in the garden environment, in purple and white forms.

At the other end of the year there are some excellent autumn-flowering crocuses to cheer up the alpine garden as winter approaches. One of the best and most readily available is C. speciosus.

Crocuses are the quintessential bulbs (technically corms) of early spring along with snowdrops. Crocustommasinianus flowers in the garden in late winter and early spring.

Today there are countless named snowdrop cultivars, many fine garden plants including the charming Galanthus nivalis ‘Sandersii’ (Sandersii Group). Snowdrops are best in groups and drifts and hearten the garden from Christmas onwards.

Sternbergia lutea relishes hot dry corners on the rock garden, flowering in the autumn. With crocus-like flowers it is actually closely related to the daffodils, Narcissus.

Technically a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial, the North American wake robins, Trillium, are classed horticulturally as ‘bulbs’. T. rivale forms small patches once established, flowering in the spring with its charming triangular-shaped flowers.

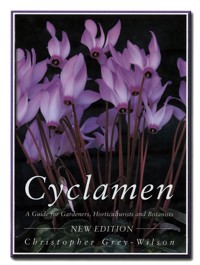

Cyclamen, especially C. hederifolium (pictured) and C. coum, are superb little plants for naturalising in the garden, easily grown and thriving in shady or part sunny places. With careful selection cyclamen can be found in flower through much of the year.

Orchids

Hardy terrestrial orchids, especially in genera such as Cypripedium and Dactylorhiza, are great favourites amongst growers of alpine plants adding a great deal of interest, especially in late spring and summer. Many of those readily available are not especially difficult to cultivate either in the open garden, in pots, or within the protection of an alpine house.

Cypripedium calceolus, the lady’s slipper orchid, one of Britain’s rarest native plants, is more readily available today because microculture techniques have allowed plants to be reared in the laboratory, thus helping conserve the plants in the wild.

An eye-catching slipper orchid, Cypripedium tibeticum, one of a number now available to gardeners.

Ferns

Although most ferns are found in the lower parts of mountains or in the lowlands, with very large numbers in the tropics, there are some excellent little ferns that attain alpine levels, generally growing in rock crevices or in screes and moraines. Ferns have a fascination all of their own; the smaller ones are ideal companions in trough and container plantings, and for planting in shady nooks on the rock garden.

Adiantum venustum, a patch-forming fern for cool, part-shaded places in the garden.

Adiantum pedatum ‘Imbricatum’.

Asplenium trichomanes.

Alpines in the wild

What is constantly surprising to many gardeners is that plants from so many parts of the world, and from very diverse habitats, whether alpines or not, can be grown side by side in the garden environment. This is what makes gardening so exciting and at times so challenging. Knowing how and where plants grow in the wild can give many clues as to their needs in cultivation. Some alpines, in the broad sense, can tolerate varying conditions in the garden, while others are less tolerant, more specific. At one time, for instance, the cushion-forming dionysias (Dionysia), close relatives of the primrose, from the hot, dry mountains of Iran and Afghanistan, were considered to be almost impossible to grow. After some 50 years of diligence and careful adaptation, there are many species and a host of hybrids in cultivation, nurtured by skilful growers, especially in Britain, mainland Europe and North America.

Habitat types can be divided into a number of major sections, but within each, other factors also play a role such as rock type, soil composition, exposure and aspect, whether sunny or shaded.

Rock types: acid, neutral, alkaline

The rock type and soil type have a great influence on the association of plants in a particular habitat. The most obvious is the rock type, especially whether it is acid or alkaline. This is particularly important in deciding how to cultivate them in our gardens, for there is no point in growing acid-loving plants in alkaline conditions. Some alpines can tolerate a wide range of rock or soil types; others are very specific. Light soils, whether acid or alkaline, often attract a different association of plants to heavy, especially clay, soils. Other factors also influence what plant grows where: factors such as sunny exposed positions or shady, sheltered ones, and the amount of precipitation (rain or snow) during the different seasons of the year.

Alpine habitats

Meadows (low and high)

Grassy meadows are a feature in many mountain regions around the world. Traditional meadows, unharmed by the use of herbicides, contain a diverse range of species. The medley of flowers, including many grass and sedge species, is one of the most joyous features of mountain walks or treks. Meadows below the tree-line are often rich and lush with tall herb communities dominating the meadows in summer. These in many areas are traditionally cut during the summer for hay, often allowing some grazing to follow. This practice has continued for hundreds of years and the richness of such meadows continues year upon year undiminished.

Above the tree-line, the meadows are far more exposed, except in well-sheltered gullies, but also harbour a rich association of species and can be as colourful as those lower down the mountains. In the Alps and elsewhere high alpine meadows are grazed during the summer months but are not cut for hay.

Meadows close to the tree-line above Paradise on Mt Rainier in Washington State, USA.

Rich hay meadows form a patchwork with deciduous and coniferous woodland in the Hautes-Alpes of SE France.

Flowery meadows primarily used for summer grazing below the Col du Petit Mont Cenis, Savoie Alps, close to the French–Italian border.

Val d’Incles in Andorra in the Pyrenees, a typical glaciated alpine valley with a patchwork of hay and grazing meadows with coniferous woodland dominating some of the slopes.

Meadows are a feature of the Zhongdian Plateau in NW Yunnan, China, here with graze-resistant Euphorbia nematocypha and Iris bulleyana.

Lush meadows of the Tibetan Marches, here dominated by Cremanthodium brunneopilosum, photographed in NW Sichuan, south or Aba, in China.

Above the tree-line, meadows are primarily used for summer grazing, the meadows dwarfed by exposure to altitude as here on the Envalira Pass, on the French–Andorran border.

A white buttercup, Ranunculus keupferi, one of the dominant high meadow species (at well over 2,000m) in the Savoie Alps.

A spring meadow in the Picos de Europa, Puerto de San Glorio, in northern Spain, with Narcissus nobilis.

Rich hay meadows above Fusio in the southern Swiss Alps, just north of the Italian border. (Photo: Phillip Cribb)

Rocky banks or outcrops often interrupt sloping mountain meadows allowing other species a niche in which to thrive; here Gentiana verna in the Vanoise National Park, SW France.

Ancient hay meadows contain a rich medley of species, often with yellow rattle (here Rhinanthus alectorolophus) an important constituent species.

Grazing, often by cattle or sheep, is an important element in mountain regions, particularly in the higher European mountains as here in the Transylvanian Alps of Romania.

At high altitudes, as here on Mt Parnassus in Greece, meadows can be sparse and often thin, sandwiched between rocky slopes. Where the snow melts in the spring, a profusion of crocuses, Crocus veluchensis, mix with blue scillas, Scilla bifolia, producing a carpet of colour.

Soon after snow melts from the high meadows plants burst into growth; here the glacier buttercup, Ranunculus glacialis, puts on a bold display below the Col de l’Iseran in the French Alps.

Carpeting Globularia cordifolia in a rocky meadow.

Marshes

Swamps and marshy areas, often fed by accompanying streams and rivulets, are characteristic at all altitudes where alpines are to be found and harbour different associations of plants to the drier habitats close by. Some plants like the marsh orchids (Dactylorhiza) and bog primroses (Primula) are well adapted to growing in marshy places and similar damp conditions are what they need if they are to succeed in our gardens.

Soldanella alpina enjoys seasonally wet places, flowering as the winter snows retreat.

Streams fed through the summer by melting snows higher up the mountain are a feature of many mountains, offering banks for moisture-loving alpines. The view here is of the Pain de Sucre, a Matterhorn-shaped peak on the French–Italian border.

Marshy meadows with accompanying pools, found at low and high altitudes, provide a suitable habitat for many moisture-loving plants like the marsh marigold, Caltha palustris.

The Matterhorn in the southern Swiss Alps, where marshy lake surrounds support a colony of a cotton grass, Eriophorum scheuchzeri. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Woods

Many plants classed as alpines by gardeners come from woodlands. Woodland has a significant presence in most mountain regions around the world from quite low altitudes to the upper limit (the tree-line) where trees are able to grow. Evergreen and deciduous trees can be found, mixed or not, in many regions. At the tree-line species are often dwarfed by altitude and the woodland thinner and more open. Woodlands are dynamic habitats for plants and animals. Within woodland, according to soil types and density, the plants can be divided into various communities from the lower herb and shrub communities to the trees themselves. Woodland is often interrupted by meadows, greatly adding to the diversity of plants and animals found in a particular area. The tree-line is not often a precise demarcation and is generally lower on the colder north-facing aspects than it is on the warmer and sunnier south-facing slopes. It also depends on the distance from the equator: in the Nepalese Himalaya the tree-line can be as high as 4,200m (13,780ft) while in northern Norway 600m (1,968 ft) may be the limit.

Coniferous forests of firs, Abies, form the tree-line in the Upper Marsyangdi Valley, C Nepal, with Nilgiri and Tilicho peaks peeping through the clouds.

Mixed deciduous woodland with conifers and deciduous trees, interspersed with meadows, are typical of many mountain regions, as here in the Hautes-Alpes, France. Above them the exposed rocky slopes reach up to snow-clad peaks and ridges.

Rocky slopes

Rocky slopes and outcrops are typical of mountain regions, often forming very extensive areas, sometimes interspersed with meadows and also with trees and woodland below the tree-line. Depending on the rock type such habitats often harbour some of the most interesting alpines such as the rock jasmines (Androsace) and saxifrages (Saxifraga). Rocky slopes can be of all the major rock types, such as sedimentary (limestones and sandstone), metamorphic (granite and basalt) or igneous (volcanic rocks and laval slopes).

Slopes of different aspects can have quite different plant associations. Here in the Georgian Caucasus the steep meadows contrast with woodland on the opposing slope, with Stachys macrantha in the foreground.

The Casse Déserte in the Hautes-Alpes, with its eroded peaks and abundant screes, appears bleak but harbours a surprising number of interesting alpine plants.

Rocky slopes present a patchwork of exposed rocks and more stable areas where various plants can gain a roothold, the colour here provided by yellow Lotus alpinus and blue Globularia cordifolia.

A natural rock outcrop in the Pyrenees with some soil-filled fissures that suit a medley of colourful alpines.

Anemone rupicola nestles amongst boulders in fragmented Abies woodland in the upper Gangheba, near Lijiang, in Yunnan, China.

Screes and moraines

Habitats composed of rock fragments of many sizes such as screes (talus slopes) and moraines left by retreating glaciers, providing they are reasonably stable, also harbour an interesting range of plants, some especially adapted to the fragmented conditions of the rocks. Rock type again influences the type and number of species that can inhabit such a restricted habitat.

Viola calcarata, normally a meadow species, thriving on an exposed slope of fractured rocks stabilised here and there by grassy tussocks. Photographed in the Hautes-Alpes.

Lateral moraines in the upper Marsyangdi Valley, C Nepal, contrast with the bare and wooded slopes close by; Nilgiri and Tilicho peaks are in the background.

A precarious hold; Geum reptans thriving on a steep scree in the Écrins, SE France. (Photo: Harry Jans)

The Upper Khung Khola Valley in Dolpo, NW Nepal, close to the Tibetan border. Screes and moraines are punctuated by cliffs and steep exposed rocky peaks and ridges. Despite its bleak appearance, the valley at over 5,000m has a sparse but quite rich alpine flora.

High alpine slopes in the Daxueshan, NW Yunnan, with scree slopes and protruding peaks and ridges contrasting with dwarf rhododendron scrub to the left.

Penstemon davidsonii on an exposed, rather bleak slope on the edge of Mt Adams in the USA Cascades, Washington State.

Corydalis benecincta, a Chinese scree-dweller, photographed on the Daxueshan, NW Yunnan.

The Mont Blanc Massif on the French–Swiss border is dominated by snowy ridges and peaks, with sweeping glaciers below. Only away from the permanent snow fields can plants take hold but, despite this, the mountain has a rich and varied alpine flora.

Cliffs

Cliffs present a fascinating habitat for plants. Crevices and ledges all provide a roothold for an exciting array of alpine and mountain plants. Some saxifrages, small ferns, and plants like Haberlea and Ramonda, are particularly well adapted to a cliff existence. The fascinating and colourful Middle Eastern genus Dionysia is almost exclusively evolved to live on cliffs. Sunny cliffs attract different species of plants from shaded ones, a fascinating study in itself. Cliff plants are technically referred to as chasmophytes.

Paraquilegia microphylla, arguably one of the most beautiful of all alpines, is a cliff-dweller at high altitudes, up to 4,300m; Baimashan, NW Yunnan.

The charming Viola delphinantha, a cliff dweller confined to the northern Balkan Mountains, here photographed on Mt Olympus in Greece.

Campanula oreadum issues from the tightest of fissures on the limestone cliffs towards the summit of Mt Olympus, Greece.

High alpine habitats

At the highest altitudes, bare rocky ridges and soaring mountain peaks dominate the landscape. Plants are few and far between and nestle anywhere they can find some shelter from the harsh environment – gullies, at the base of large rocks or in crevices.

Another bellflower, Campanula andrewsii, although grown as an alpine, is endemic to rocks and cliffs close to sea level in the south-eastern Peloponnese, Greece.

Campanula cenisia photographed in the Swiss Valais (Wallis) is a denizen of bare rocky habitats, nestling amongst the rocks and on cliffs. (Photo: Harry Jans)

A classic alpine, Gentiana verna, photographed in the French Alps close to the Col du Galibier.

Conservation

A whole range of alpines are already well-established in cultivation. Except under very special circumstances (research in particular), there is no need to dig up plants from the wild. In many countries it is against the law to dig up or collect plant material from the wild without permission; this includes cuttings and seeds as well as whole plants. Such bans may cover the entire country, but will certainly cover national parks and reserves within their boundary.

Corydalis latiflora, a high-altitude Himalayan endemic, thrives in rock crevices and on rough screes; Nepal, Dolpo, Khung Khola.

Today everyone recognises the need to cherish and preserve our natural environment. The temperature increase due to global warming is having a marked effect on alpine communities around the world, most obvious from the clear signs of retreating glaciers and melting icecaps that have been carefully and scientifically monitored. While wildlife, both animals and plants, can adapt to slow and gradual change over prolonged years, many cannot cope with the rapid change that we have seen in recent times. This is all the more reason to cherish and preserve the great range of alpine species already in cultivation to ensure their future in our gardens, although some adaptations will need to be made with the increasing threat of warmer and drier summers in many parts of western and northern Europe and in North America in particular.

CHAPTER 2

ALPINES IN THE GARDEN

Alpine plants have never been more popular or diverse than they are today. Many gardeners have at least some alpines in their gardens while some growers specialise in a wide range. Most garden centres and even some supermarkets sell a selection of alpines. The more adventurous garden centres put on small displays of alpines and other small hardy plants to show the ways that they can be grown in the garden. For those keen on expanding their range of alpines then there are nurseries scattered in Britain and in Europe and elsewhere, offering an exciting range of alpines, many not available anywhere else. Added to this there are societies and clubs specialising in alpine plants: in Britain there is the Alpine Garden Society (AGS) and the Scottish Rock Garden Club (SRGC), in America the North American Rock Garden Club (NARGS) and there are others in Holland, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Japan and New Zealand. The Alpine Garden Society, with which I have had a long association, offers annual membership for individuals, a much sought-after and profession journal, The Alpine Gardener, and newsletters, regional groups with lecture programmes and garden visits, shows in many parts of the country, an annual seed exchange offering many alpines not easily obtainable elsewhere, foreign tours and a dynamic and relevant website.

The spring garden burst into bloom with a multitude of primroses in various colours, with Lunaria ‘Corfu Blue’ in the background.

General considerations

Generally speaking, the majority of alpine plants require a sunny, open position in the garden or one with dappled shade during the hotter midday hours of summer. Well-drained gritty compost will ensure that the plants root down well into the soil and that the vulnerable necks of many are kept relatively dry and free from rotting, especially during the winter months.

Woodland alpines, on the other hand, relish shade or dappled shade and moist yet well-drained humus-rich soils; soils rich in organic matter, leaf mould or garden compost. Soils that are prone to waterlogging are the chief enemy of nearly all alpine plants except for those that like marshy conditions in the wild, such as bog primulas.

Soil type is also important. Many gardens naturally have an alkaline soil which is suitable for many alpines but not for those that require a neutral or acid soil. To grow acid-loving alpines, or indeed any other acid-lovers, on alkaline soils is a complete waste of time. This does not mean that acid lovers cannot be grown but it does require some planning. For instance, pockets of acid (ericaceous) compost can be created with care on the rock garden. Easier still is to fill raised beds, troughs or containers with acid compost, thus increasing the range of alpines that can be grown in the garden. Soil alkalinity is measured on a pH scale of 1–14 where pH7 indicates a neutral soil, everything below 7 is acid, and everything above is increasingly alkaline.

Heavy clay soils can be greatly improved for alpine plants by digging in ample quantities of sharp horticultural grit. Compost bought from the local nursery or garden centre can also be modified by adding extra grit. Generally speaking, a good standard compost mix is one part by volume of sterilised loam (potting compost is a good substitute), one part of sieved, friable, garden compost, one or two parts of horticultural grit or, in some instances, coarse sand (builders’ sand is generally unsuitable, tends to clog composts and if of coastal origin is very likely to contain harmful salt, injurious to the majority of alpine plants).

A good acid compost consists of three or four parts of finely sieved lime-free leaf mould or peat substitute, e.g. ericaceous compost (see note below), or even finely composted bark, mixed with one or two parts of sharp sand.

Compost can be readily modified to suit different types of plants. For instance, many cushion-forming rock jasmines (Androsace), pinks (Dianthus) and saxifrages prefer even grittier, perfectly drained compost reflecting the rocky habitats many occupy in the wild.

Suitable chippings (there are many different ones available at garden centres and large nurseries from fine to coarse rock chippings and from acid to alkaline) placed around plants, whether in troughs or containers or in the larger expanses of the rock garden, can enhance alpines by keeping down weeds, helping to keep the roots cooler during hot weather, while at the same time being aesthetically pleasing to look at. Troughs and containers with acid-loving alpines can be dressed with bark chippings to good effect.

Whatever features are employed in the garden they can be an important part of the overall design of the garden rather than random features. An area set aside especially for a collection of troughs and containers of different types can be an arresting feature on its own; a pool adjacent to a rock or scree garden can greatly enhance the garden, whilst also benefitting from attracting a variety of wildlife into the garden.

Note: peat gardens and the use of peat was widely advocated in former times and the peat garden was a great adjunct to the alpine garden; however, the depletion of peatlands in Europe and elsewhere and the damage done to the environment by extraction has led to a ban of peat products in many places. Today its use in gardening can no longer be tolerated. Instead, suitable alternatives need to be sought. Manufacturers produce various composts, such as alkaline-free ericaceous compost designed especially for acid-loving plants and composts based on coir and other waste products and these are readily available at garden centres and some nurseries. Leaf mould can be a very useful alternative; well-rooted and finely-sieved, it makes a wonderful foundation for various composts and to build up raised beds for alpines, especially woodlanders that require moist humus-rich compost or mulching. Where space allows, an enclosure into which leaves can be deposited in the garden is a fine way of recycling natural waste products. Leaf mould takes several years to rot down into a suitable product that can be used in the garden.

Rock gardens

A well-constructed rock garden can be an impressive sight in a garden and a great place for growing a whole range of colourful alpines; however, rock is expensive and heavy to move around. Unless you are lucky enough to garden in a rocky area then a formal rock garden is neither practical nor realistic. It is not necessary to have a rock garden with outcrops of large rocks and soil-filled crevices in order to grow alpines successfully. An area with a few rocks tastefully placed can give the impression of an outcrop without involving great expense. Most good garden centres and other outlets supply rock of different types for ornamenting the garden. This makes it possible to select the best rocks individually: they are sold by piece or for larger quantities by weight. Rock type varies but hard limestone or sandstone is perhaps preferable for the majority of alpine plants. Granite can be used but offers rather featureless lumps. Friable oolitic limestones (such as Cotswold) and shales are generally unsuitable and readily subjected to frost damage during the winter.

Nonetheless, rock gardens can be hugely impressive and there are great examples in Britain (Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Edinburgh Botanic Garden, the Royal Horticultural Society Gardens at Wisley in Surrey and Harlow Carr near Harrogate, Cambridge Botanic Garden, the garden of the Alpine Garden Society, Pershore, Worcestershire, not to mention some superb rock gardens in private hands). Abroad there are also some supreme examples of the rock gardeners’ art: Gothenburg Botanic Garden in Sweden, Tromsø Botanic Garden, Norway, Würzburg Botanic Garden in southern Germany, the Lauteret Botanic Garden in the French Alps, Garmisch Partenkirchen in Bavaria, Utrecht Botanic Garden in Holland, Denver Botanic Garden in Colorado …. There are many more, especially private gardens, for example in the Czech Republic.

Part of the extensive rock garden at RHS Wisley, Surrey.

A colourful display in a corner of the large rock garden at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The private rock garden of Glenn Shapiro in Silverdale, Lancashire, with colourful rock phloxes.

Part of the rock garden at Gothenburg Botanic Garden.

The waterfall issuing over a natural rock outcrop at Gothenburg Botanic Garden, Sweden.

New rock garden construction at the RHS Harlow Carr. (Photo: Robert Rolfe)

Scree gardens

Screes are accumulations of rocky debris beneath cliffs and ridges in mountain areas around the world, resulting from weathering, especially from frost damage fragmenting rocks. Moraines have a similar effect in that glaciers push rocky debris to the sides and end of the glacier as they advance and retreat. Whatever their origins, many alpines relish fragmented rocky areas in the wild provided they are fairly stable. Scree-type mixtures with rock fragments of different sizes based on suitable alpine compost make an interesting feature for pockets in the rock garden, or for raised beds. At Edinburgh Botanic Garden, scree beds extend from part of the extensive rock garden onto the lawns and are full of an exciting range of alpine plants and some small shrubs.

Part of the rock garden and scree at Branklyn Botanic Garden in Scotland.

Edinburgh Botanic Garden; a corner of the rock garden with Campanula ‘E.K. Toogood’ in the foreground.

Crevice gardens

In recent years the tendency has been to move away from the formal rock garden with its large outcrops and terraces to a more intimate structure in which pieces and shards of rock are wedged together in an upright or slightly inclined position, leaving enough gaps to accommodate a range of plants. There is evidence that strongly suggests that alpine plants grow even better in a crevice garden than they do in the more formal open rock garden. Additionally, the rocks being smaller and lighter are easier to manipulate and the cost of transport generally less than moving large rocks around. Any rock type that splits into plates is suitable, although most crevice gardens are composed of limestone; however, substitute rock such as broken paving slabs and old, thick roof tiles can be employed very successfully.

Crevice gardens can be any shape, depending much on the space available in the garden. On a smaller scale a crevice area can be made on raised beds or in large troughs. For most alpines an open sunny site is best; however, a shaded crevice garden can be an attractive feature for small ferns and alpines like ramondas and haberleas and other shade-lovers. Crevice gardens can be flat or raised like an escarpment, building up the rocks on a layer or mound of suitable alpine compost and filling in the crevices created with further compost as construction proceeds.

The crevice garden at the AGS (Alpine Garden Society) Garden, Pershore, Worcestershire.

Detail of the AGS (Alpine Garden Society) crevice garden showing the juxtaposition of vertically placed rock slabs and gritty compost infill.

A sloping crevice garden in May, planted with alpine phloxes and other colourful cushion alpines.

Rock crevices attractively occupied by various houseleeks, primarily Sempervivum arachnoideum and S. montanum.

General view of the rock garden at the AGS Garden, Pershore, Worcestershire.

Scree garden, AGS Pershore, Worcestershire.

Artificial scree created near Gothenburg in Sweden by Peter Korn, where alpines are allowed, within reason, to self-sow.

Young plants, plugs and rooted cuttings can be easily infiltrated into suitable crevices without harming them. Larger plants are more difficult to introduce into the small crevices between the vertical rocks without damaging them.

An established crevice garden can be a delightful feature in the garden, adding interest for many months of the year. They are suitable for a wide range of different alpine plants, although it is best to avoid any that are too large or invasive.

Raised beds

For those who cannot justify the cost of building a formal rock garden or simply do not have the space, then a raised bed may be the answer. Raised beds provide a perfect environment in which to grow many alpines, including small bulbs. They can be constructed of brick, stone or sleepers and to any height, remembering that it takes a great deal of compost to fill a large, deep raised bed.

Raised beds can be any shape and can be an integral part of the overall design of the garden. With stone or brick, curves can be achieved easily, while sleepers are more rigid and confining.

The height of a raised bed is a matter of choice but those two or three bricks in height or sleepers set on edge is all that is necessary for a simple and easily constructed raised bed. Raised beds can be made much deeper and constructed with disabled or wheelchair-bound gardeners in mind.

Once filled with compost, raised beds can be decorated with rocks if desired and, once planting is complete, a dressing of suitable rock chippings can be strewn across the bed and carefully tucked in around each plant. Chippings (limestone of various kinds, granitic chippings and slate are all available) can enhance the bed and are a great benefit to the plants themselves, helping suppress weeds and keeping the vulnerable neck of choice alpines free from excess moisture that can cause rotting, especially during the winter months.

Erinus alpinus and Aethionema × warleyensis ‘Warley Rose’ combine on a raised scree bed in the author’s garden.

A brick raised bed filled with a gritty alpine compost in the author’s Suffolk garden.

The corner of a brick raised bed with Campanula tommasiniana and a dwarf form of Genista tinctoria.

A round raised bed created using old bricks to contain a gritty alpine compost, lumps of tufa and a variety of colourful alpines, seen here in the late spring.

A raised bed composed of wooden slats, filled with a humus-rich acid compost, supports a colourful display of dwarf rhododendrons and graceful blue Corydalis flexuosa ‘China Blue’.

A simple raised bed made with wooden sleepers and infilled with a gritty alpine compost can support a surprising number of alpines.

Dry and retaining walls

Retaining walls are intended to hold back a bank or terrace in the garden and can be constructed carefully from brick, stone or sleepers. At the top of the retainer a narrow or wide bed makes an excellent place to grow alpines, allowing some to grow attractively over the edge. Small gaps left in brick- or stone-work as construction proceeds allows interesting little nooks for additional alpines, the selection dependent on the aspect, whether sunny, part or wholly shaded. Some alpines like certain campanulas, saxifrages and ramondas ideally suit crevices and are best planted as young plants. Some, like the fairy foxglove (Erinus alpinus), will self-sow readily into the slightest crevice, greatly enhancing the retaining structure.

A retaining wall decked with yellow alyssum, Aurinia saxatilis and aubrieta, backed by colourful spring bulbs.

Troughs and containers

Troughs, stone or artificial, are perfect for growing alpines, providing a mini-environment for a range of colourful little plants. Troughs come in a wide range of shapes and sizes and depths. The majority of old stone troughs are rectangular and vary a great deal in depth from 15cm to over 60cm. Other shapes include circular, half-circular and oblong. Stone troughs nicely planted and enhanced by pieces of suitable rock can make a great feature in the garden and ideally suit today’s small gardens and, with a careful selection of plants, can provide interest through many months of the year. Although stone troughs are available, especially through antique centres, auction houses and reclaim yards, they tend to be very expensive. The good news is that there are some excellent and relatively inexpensive alternatives. Artificial stone made from various resins and fibreglass, plastic and other modern materials can result in very realistic looking troughs (for instance, stone, lead or slate look-a likes) and containers and these are widely available at garden centres, home and garden stores, and online.

A fine antique stone water trough displayed at RHS Harlow Carr.

Slate and stone troughs cluster close together in the author’s garden.

The front garden designed around a trough, tufa and a rock pillar arranged to accommodate a wide variety of alpine plants; Harry Jans, Loenen, Netherlands. (Photo: Harry Jans)

A semi-shaded trough at RHS Harlow Carr, with a silver saxifrage, Saxifraga cochlearis, miniature ferns and Primula allionii. (Photo: Robert Rolfe)

An artificial resin-based trough, planted with Rhodohypoxis and a small Astilbe. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Integrated stone trough with rockwork in a space allocated in paving at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. (Photo: Harry Jans)

A trough by Jan Lubbers, Netherland, packed with succulent alpines, sedums, sempervivums and a yellow-flowered Delosperma. (Photo: Harry Jans)

An artificial trough containing a miniature stone crevice garden planted with various saxifrages. (Photo: Harry Jans)

A humus-filled trough planted with small ferns (Adiantum and Cheilanthes) can provide an interesting feature in a shady part of the garden. (Photo: Robert Rolfe)

A small, hollowed sandstone rock just 55cm across provides a home for several houseleeks, including Sempervivum arachnoideum in flower.

A stone trough at East Ruston, Norfolk, planted simply with a colourful display of small pansies and violas.

A trough burgeoning with colour: Phlox nivalis ‘Nivea’, Polygala calcarea ‘Lillet’ and Aquilegia ottonis subsp. amaliae. (Photo: Robert Rolfe)

Tufa

Tufa, or travertine, is an especially interesting rock type which some alpine gardeners have found excellent for growing some of the more demanding alpines. Tufa is a carbonate of lime deposited by streams and rivers rich in the mineral where the water is checked by barriers such as waterfalls, but it will also deposit around obstacles in the water such as other rocks, fallen trees or roots. In time, over thousands of years, the deposits can build up into impressive thicknesses, so much so that in some countries, like Italy, tufa is carved into blocks and used for building. Small quantities of tufa are sometimes available in Britain and elsewhere both at garden centres and often at aquarium suppliers. Firm to hard tufa, rather than soft tufa, is most suitable. Tufa has several important qualities, the most important being its light weight and its porosity. Placed on the ground or partly dug into the soil the tufa will draw up water through a fine network of pores. Larger blocks, say 90–150cm across can be drilled at an angle to provide planting holes for young alpine plants. Discreet, slow-growing and non-invasive plants are the best (see suggested list on page 283).

Pieces of tufa can also greatly enhance raised beds and troughs, the plants grown in the tufa or sandwiched between smaller pieces.

A tufa bank in Harry Jan’s alpine house, Loenen, Netherlands, planted with dionysias, Primula allionii cultivars, drabas and other colourful, discreet alpines. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Daphnes, drabas and dionysias inhabiting a section of tufa wall. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Tufa blocks supported by stone columns in Harry Jans’s garden in the Netherlands, ideal for establishing some of the trickier and more demanding alpines in the open garden. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Yellow Dionysia aretioides and a selection of Primula allionii cultivars happily established on a tufa wall. Josef Mayr, Würzburg, S Germany.

Saxifraga longifolia, a monocarpic lime-encrusted species, forms attractive symmetrical rosettes which enlarge over several years before flowering. (Photo: Harry Jans)

Saxifraga longifolia in flower, growing on a tufa block. (Photo: Harry Jans)

A stone trough packed with tufa provides a great home for discreet, non-invasive, alpines.

Hypertufa

Hypertufa is an artificial rock that, when used carefully, can mock real stone, even acquiring mosses and lichens in time. Today, when real stone troughs are scarce and expensive, hypertufa offers a cheap and easy alternative. Troughs can be created using moulds and hypertufa mix, or used to coat old, glazed sinks. The mixture is a simple one, using one part by volume of coarse sand or fine grit, one part cement and two parts ericaceous (non peat-based) compost (fine bark chippings or sieved garden compost can make a suitable alternative), mixed together into a thick paste. Glazed sinks need to have extra drainage holes drilled through the base and be covered liberally with a bonding agent such as an epoxy resin, to ensure the covering of hypertufa holds firm. A coating 20–30mm is about right covering the whole of the outside of the sink and the top 40–50mm of the inner surface.

Artificial troughs and sinks are best constructed in situ as they can be very heavy and difficult to manoeuvre around the garden. They can be an attractive additional feature to the alpine garden. A series of different shapes and sizes can be very effective and create numerous niches for small alpine plants.