Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

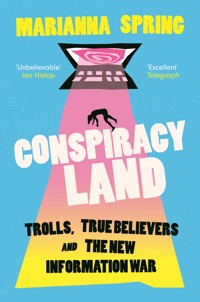

'Unbelievable' Ian Hislop 'A tour de force' Jeremy Vine 'Excellent' Julia Ebner, Telegraph MY NAME IS MARIANNA SPRING AND SOME OF MY TROLLS SAY THEY WANT TO KILL ME Ever since she became the BBC's first disinformation and social media correspondent, Marianna Spring has delved into the worlds of media manipulators and conspiracy theorists. Meeting face-to-face with architects of hate and fake news, she discovers how people come to believe that terrible atrocities are staged, and that pandemics and climate change are the tools of an invisible elite bent on world domination. Told with curiosity, urgency and, most of all, empathy, Conspiracyland pulls back the curtain on the information battle threatening us all, and bears witness to the real-world consequences that lie beyond our screens. 'A crucial read for understanding the intricate web of misinformation that influences our modern world' Eliot Higgins, author of We Are Bellingcat

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Marianna Spring is the BBC’s first disinformation and social media correspondent and an award-winning journalist. She presents podcasts and documentaries investigating disinformation and social media for BBC Radio 4, as well as for BBC Panorama and BBC Three. She is also one of the presenters of the BBC’s Americast podcast. She has been named the British Press Guild’s Audio Presenter of the Year and Royal Television Society Innovation winner.

First published in hardback as Among the Trolls in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Marianna Spring, 2024

The moral right of Marianna Spring to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 526 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 525 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Mum, Dad, and everyone I love but can’t name because of the trolls.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 True Believers

2 The Non-Believers?

3 Collateral Damage

4 Escaping the Rabbit Hole

5 The Life of a Lie

6 Shock Troops

7 Bot or Not? How State-Sponsored Disinformation Works

8 Virtual Is Now Real

9 What Next?

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

INTRODUCTION

I was five years old when hijackers flew planes into the Twin Towers in New York on 11 September 2001. My mum collected me from school and told my teacher what a terrible day it was. As we walked home, I asked her what had happened. She explained how these aeroplanes had been flown into the towers on purpose. I kept asking her – was it an accident? To which she would reply ‘no’. I couldn’t get my head around how something like that could happen deliberately. It was terrifying.

In the weeks and months that followed the attack, conspiracy theories about 9/11 proved very popular. Rather than spreading like wildfire on social media, they unfolded in chatrooms and on websites, via DVDs and talks. I often think back to that moment. Partly because it explains a lot of why I wanted to become a journalist – I wanted to understand why bad things happen and reveal it to other people. And partly because it was my entry point into the world of conspiracy theories, somewhere I’m going to call Conspiracyland.

We all to some degree want to make sense of the chaos around us. We want to be able to predict when people could cause harm. We want to be one step ahead of them. The way my five-year-old brain couldn’t understand the attack in some ways mirrors the mentality of the people who deny it ever happened, in spite of the evidence. We all find it difficult to make sense of. Except the explanations spun by conspiracy theorists about 9/11 were much more complicated and much less innocent than my ‘well, maybe they didn’t mean to’.

The people who believed and pushed these conspiracy theories were the founding fathers of Conspiracyland. It isn’t a real place, of course. The only way inside is by falling down the rabbit hole. Not quite in the same way as in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where Alice chases after a flustered white rabbit with a pocket watch and finds herself in a whole new universe. You just have to venture into certain parts of the online world, and you’ll find yourself tumbling very quickly.

I’ve spent a lot of time exploring the UK’s Conspiracyland in particular. Sometimes, I’ve heard or read as many as ten impossible things before breakfast. You’d be mistaken in thinking this is a universe limited to social media. It’s a parallel world where everything is topsy-turvy. It has its own leaders, its own holiday retreats, its own protests, its own festivals – and its own media, from video channels to conspiracy theory newspapers. Everything you think you know – well, in Conspiracyland it’s the opposite. The beliefs some of its members hold extend far beyond legitimate concerns, fears and questions of wrongdoing. Real examples of corruption and conspiracy are extrapolated and used to declare that almost everything is staged – from global pandemics and climate change to wars and terror attacks.

Some of the inhabitants of Conspiracyland are fluent in hate and blame. In modern-day Britain, a committed minority calls for the execution of journalists, politicians, nurses and doctors, based on an unflinching belief in disinformation stating that these people are complicit in sinister plots to harm people. But there’s no evidence to back up these grand plans, and even the most powerful people in the world would struggle to pull them off.

As the BBC’s disinformation and social media correspondent, I spend my days investigating this strange new world. And I frequently come face-to-face with people who really don’t like me very much. Between January and June 2023, I received 11,771 of the 14,488 abusive messages escalated in the BBC’s own system designed to detect hate. Conspiracyland is not limited to one place in Britain, either. It’s infected towns up and down the country. Anywhere with an internet connection, you’ll likely be able to venture into it.

It might seem a faraway place for some of us. But all of our social media feeds can distort the world around us. We can be constantly exposed to subjective and polarized online worlds, and pushed more and more of what we want to see by automated computer systems – algorithms. They use the hundreds of clues we give them every day to figure out who we are and what we like. They drive us to places and people we otherwise might not have found. They push us further to the extremes. Politicians and influencers and anyone else chasing likes and power weaponize that fact. Nuance and moderate viewpoints can be rare in this universe. No one is immune to these powers, and the consequences are far from fringe and inconsequential – for individuals, communities and societies.

At the most extreme end, there have been conspiracy-theory-driven riots at the US Capitol and a coup attempt foiled in Germany. Disinformation and hate have driven apart local communities. Victims of war have been targeted by ruthless propaganda campaigns waged by governments. Survivors of terror attacks have been told their injuries were faked. Healthcare workers, reporters and politicians have had their lives threatened by those in the online world just for doing their jobs – myself included. Lies about illnesses and vaccines have caused people to lose their lives. Families have been fractured by one person’s belief in conspiracy theories, isolating them from those they love the most. Elections in Brazil and Ethiopia have been plagued with mistruths. There are threats with real-world consequences. More so than ever, what’s happening on social media is bleeding into all of our lives – and it’s having a huge impact.

I don’t reside in an ivory tower. I go out and meet the conspiracy theorists, the trolls and their victims, and everyone else affected. I travel all over the UK, and across the world, so I can uncover for myself what’s happening. My focus is primarily on the disinformation war waged on British soil, but that connects up with the one being waged everywhere.

I’ve eaten fruit in an anti-vaxxer’s kitchen with a blind cat, doorstepped a disaster troll at a market stall in a Welsh town and unearthed the conspiracy underbelly swelling in the picturesque town of Shrewsbury. I’ve been called a bitch while attending conspiracy theory rallies in Devon by a protester who claimed that’s not what they were doing, confronted my own trolls and quizzed the editor of a conspiracy theory newspaper in a pub with multiple cameras rolling.

I’ve cried with a grieving mum as I stood in the bedroom she still hoovers for her son, and I’ve had cups of tea with people who’ve been told that the worst day of their life never happened. I’ve met social media insiders in mysterious hotel rooms and had one of the world’s most powerful social media bosses tweet a picture of my face. I’ve gone on car journeys with true crime TikTokers. I’ve interviewed people caught up in wars accused of acting, and I’ve wandered around French towns looking at looted shops and smashed windows, the flames of violence fanned by social media.

I’ve huddled in my bedroom with five phones featuring fake characters I created to enter subjective social media worlds, and then flown with those same phones to Washington and Milwaukee to match up what these characters were seeing online to the experiences of real people. I’ve spoken to the bravest truth-tellers in the Philippines targeted by the worst online abuse, doctors who are the recipients of death threats, and journalists attacked in Germany by people who seemed to believe disinformation.

It became clear to me early on that this was so much more than bots – inauthentic accounts used to manipulate online conversations. I wanted to understand the real people caught up in this world, who are often there at great risk to themselves and others. Through their stories, I want to show who really believes this stuff, how this problem manifests – and how it’s shaping the world around us. From podcasts and investigative documentaries to online, digital, radio and TV news bulletins, my hope has been to report on this for everyone.

Before we get started, let me introduce you to the language of Conspiracyland and how some of the terms I’ll be using interact with each other. Let’s begin with the basics.

What’s a conspiracy theory? It’s defined as the explanation for an event that relies on a belief in a conspiracy being carried out by powerful groups – when other explanations are actually a lot more likely. Conspiracy theories are characterized by a lack of evidence, and are often more about feelings and suspicions than cold, hard facts. In this book, the conspiracy theories I’ll be explaining aren’t the quirky ones we often like to indulge. They’re not fantasies with little or no consequence – for example the idea that the moon landings were staged, or that aliens exist.

Instead, they are more sinister theories that suggest global events affecting all of us are staged in some way as part of a plot. Think of anything bad that’s happened over the past few years, and someone in Conspiracyland thinks the government and powerful people faked it. These theories are often all at once totally unwieldy and too complex to follow and also very black-and-white. This politician has lied before and is accused of corruption (true) and therefore they are part of a plot to kill us all with vaccines but are pretending they are not (not true). Conspiracy theories can come true, of course – and it’s important to underline early on that the extreme theories being shared online have somewhat undermined the interrogation of real allegations of plots and wrongdoing.

These conspiracy theories sit adjacent to misinformation and disinformation. The difficulty with conspiracy theories is that, since they often rely on allegations of complicated, sinister plots for which there isn’t any evidence, it’s harder to categorically disprove them. Rather, they’re characterized by an absence of evidence – and their improbability.

Misinformation is the catch-all term used to describe the spread of misleading claims. Crucially, intention isn’t required. Disinformation, however, refers to the deliberate dissemination of false information. Take, for example, the Russian government claiming that someone caught up in an attack they’ve waged in Ukraine is really a paid actor who is just trying to make Russia look bad. When talking about disinformation, it’s important to think about its purpose. It’s usually about deliberately undermining the truth because it’s beneficial to the person lying; whether that’s because it convinces a population that their government hasn’t hurt civilians with bombs, or – on a smaller scale – because the person spreading this mistruth can make money and grow a following out of it.

Trolling has become a weapon for those who disseminate disinformation or promote conspiracy theories. Very aptly, the term itself seems to derive from language about hunting, and less so from fairy tales about trolls living under bridges. The old French term troller means ‘to wander around looking for something to kill’ or ‘to go hunting for game with no specific purpose’.1 Trolling is in its essence sending out provocative and mean messages purely for a reaction. It’s all about getting a rise out of someone.

These days, trolling is much more synonymous with inflammatory and offensive comments online. Those caught up in false allegations or implicated in these conspiracy theories about shady plots can find themselves prime targets for hate. That’s how this works. It’s about finding someone specific to blame for what’s going wrong. Only, instead of being righteous, the anger is often misplaced. You’re not just disagreeing with someone; you’re going as far as threatening them. You’re targeting who they are rather than what they’ve done, and it can all get very nasty.

This beat didn’t exist when I was born – but it is now crucial to understanding the modern world and where we’re all headed. Conspiracyland ultimately poses a threat to the fabric of our society. After all, the democracies we live in are built on the concept of a shared reality, a universal truth. You and I can both look up at the sky and agree that it’s blue. I might like that it’s blue and you might hate the colour, but ultimately we agree it exists. But if you don’t think the sky is there at all, we can’t have any kind of rational conversation about it. When the objective truth is out of our reach, we’re in trouble.

In the past, the world of conspiracy theories and hate was very different. As recently as a decade ago, you might have thought of online trolls as lonely basement-dwellers posting inconsequential, nasty remarks on internet forums. While disinformation has always plagued our society, it was spread in a different way – via the front pages of specific newspapers, and the mouths of certain politicians. Spin is nothing new, and it is true that politicians and powerful people lie and have always done so. Think of the ruins in Pompeii, where propaganda is scrawled on the walls. As journalists, it’s our job to investigate and hold the powerful to account for their mistruths. Rumour is not new, either. Gather a group of human beings in one space for any period of time, and whispers will begin to spread.

But before, the speed at which this propaganda, speculation and disinformation could spread was just a lot slower. Conspiracy theories, too, weren’t quite so widespread or pervasive. They were used to explain events that had happened a while ago, whether that be the death of the Roman emperor Nero or the assassination of the US President John F. Kennedy. They didn’t apply to day-to-day life or explain the present in quite the same way they do now.2

Social media has just made it a whole lot easier for everyone who believes these ideas to connect with one another – and to reach other people who are vulnerable to some of these beliefs and behaviours.

The online world is now impossible to untangle from reality, and therefore the disinformation and hate that proliferates can affect everything: the leaders we elect, the way our economy works, the quality of public debate, the way we conduct our relationships, the jobs we choose. This didn’t happen overnight – all of the elements involved have been present to varying degrees for a long time. But it’s in recent years they’ve blended together and become turbocharged. We are all living through a golden age for misinformation and hate, and to some extent we’re all taking part.

After all, the rise of social media has fundamentally shifted how our world works. All of us have the power to post and share and comment and connect with others online in a way that wasn’t possible before. Social media feeds constantly update us on everything from friends to politics to disasters, and for some it’s increasingly the only place they turn to in order to figure out what’s happening.

Data from the UK’s media regulator Ofcom has shown how younger people turn less to the news on the TV and radio as their first port of call to figure out what’s going on. Less than two-thirds of 16- to 24-year-olds in Britain get their news from the TV. Instead, they rely on the online world, and social media feeds play a key part in that.3 There’s a myth that misleading and hateful content online affects older people who are less native to social media, but this kind of evidence suggests it’s also younger people who are hyper-exposed to all of this.

Loss of trust in traditional media has contributed to the boom in conspiracy theories. Without a doubt, journalists are guilty of getting it wrong. Those deeply immersed in Conspiracyland, however, now disbelieve almost everything that what they call the ‘mainstream media’ say, even when it’s backed up by evidence.

To some extent, I also think that’s because some traditional media outlets have been squeamish about investigating the darker corners of social media, ones that our readers, viewers and listeners are likely to have encountered. There are fears about amplifying the people who promote harmful ideas and giving them a platform. I’m driven by exposing disinformation, hate and polarization that cause serious harm and often reach a significant number of people. We can’t pretend this is not fundamentally affecting society, and we can’t be passive observers either.

Only now are conversations about regulation and moderation of the major social media sites really beginning. These companies wield as much power over society as many governments. Even then, spiky debates over free speech – ironically turbocharged by the hyper-polarized forums that social media creates – infect discussion about how to better protect users online. I’m not a campaigner, I’m an investigative reporter. It’s not my job to come up with solutions, but I can hold companies to account and expose what’s happening. Increasingly, social media insiders are agreeing to speak to me and reveal the impact these sites can have. We’re the guinea pigs, and their insights can tell us so much about how this could be changing each and every one of us.

This isn’t just about social media, either. There are various different ingredients required for Conspiracyland to exist and flourish. Political upheaval and major global events play a role in creating uncertainty, anxiety, fear and questions. Everything from the Brexit referendum to the Covid-19 pandemic, war breaking out in countries like Syria and Ukraine, climate change and the cost-of-living crisis, has exacerbated division and distrust. A tidal wave of falsehoods and conspiracy theories has accompanied these kinds of events. And when disinformation is legitimized and fuelled by politicians and leaders, that plays a part, too.

Right now, it feels like we’re at a crossroads. Everyone is waking up to this problem and asking, ‘Where’s the accountability?’ I’ve covered several cases, both in the UK and internationally, where people targeted by disinformation and hate are turning to the courts for justice against the conspiracy theorists targeting them.

In the US in 2022, alt-right conspiracy theorist radio host Alex Jones sat in court in front of a mum and dad who’d lost their six-year-old son, Jesse Lewis, in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut in 2012. Jones had spent years suggesting this attack was staged in some way, during which time his online following grew significantly. The victims’ families described the hate they had faced as a result of the conspiracy theories. We are real, they told him. He was our son. He had to admit in that courtroom that the shooting was real – and he was ordered to pay almost $1.5 billion in damages to those families.

Survivors of the 2017 Manchester Arena attack also decided to take action against a conspiracy theorist in the UK who was attempting to deny what they lived through, and a woman in Dublin took a conspiracy theory newspaper to court which had used a photo of her son to suggest his death could be linked to the Covid-19 vaccine when it wasn’t.

These people are taking matters into their own hands. They no longer want to rely on social media sites or policymakers to tackle the disinformation and trolling they face. Instead, they are choosing to hit conspiracy theorists where it hurts most – through legal action targeting their wallets. Maybe that is the best way to deter and even stop the individuals doing this. After all, the conspiracy industry to some extent thrives on the money and power these theories can generate. But it comes at a cost for those taking action too, as they can find themselves on the receiving end of even more hate as – like me – they call out and uncover what’s happening.

Although this book doesn’t pretend to offer all the solutions, it will at least show how the problem manifests. Because we’re all living among the trolls now – and just by recognizing the scale of the problem, we can play a part in defending against the harm it causes.

1

TRUE BELIEVERS

I spend a lot of time down rabbit holes – the secret worlds inhabited by people with polarized beliefs where fiction trumps fact. How did they end up down there? The descent often starts with real fear, a legitimate question, a worry. Once you begin to tumble, it’s very hard to stop. Your view of the world fundamentally shifts. Everything is part of a sinister plot and everyone is against you.

Over the centuries, disasters, floods, poisonous algae, wars, famine – you name it – have been explained by conspiracy theories and folk tales. It’s an understandable way to make sense of catastrophe when conclusive explanations are scarce. Only, back then social media wasn’t around to amplify these ideas to millions and connect those looking for answers, who are then drawn to alternative explanations.

The Covid-19 pandemic seemed to suck in more believers than ever before, and we shouldn’t really be surprised at all. Psychologists have pointed to catastrophe as a key trigger for conspiracy theories – professor of social psychology Dr Karen Douglas states that they ‘tend to prosper in times of crisis as people look for ways to cope with difficult and uncertain circumstances’.4

As the pandemic progressed, fault lines began to emerge. Not necessarily between political parties, but rather between people who believe and trust in the fundamentals of democracy, in health officials and doctors, in institutions, and those who don’t. There are lots of reasons to distrust the powerful – politicians and governments – but this went beyond that. For some, there was a total loss of faith in what we rely on to coexist in a functioning society where we can speak freely and all agree on the objective truth.

As the pandemic eased, the fault lines deepened. Those who had become embroiled in this world didn’t turn around and admit to having lost sight of the truth. They didn’t untangle their legitimate concerns and questions from the extreme conspiracy theories declaring that Covid-19 was a hoax. Instead, they doubled down. That’s why I want to start with the pandemic, and the anti-vaccine conspiracy theories that proliferated.

An important question is undoubtedly why people believe conspiracy theories in the first place – and that was at the forefront of my mind when I covered two different protests during the pandemic: an anti-lockdown march in Sussex and a so-called freedom rally in Devon.

* * * *

The sunny coastline of Brighton is decorated with a gaggle of conspiracy-believing Santas. The people gathered together are dressed up in whatever festive attire they could get their hands on, many with Father Christmas hats. It’s a chilly December morning in 2020, and Covid-19 cases are rising in the UK. Having paraded through Brighton’s Lanes alongside this bunch, I’ve returned to its original starting point, the Peace Statue in Hove. The group begins to disband, still decorated with tinsel and Christmas decorations.

You’d be forgiven for thinking this was an eccentric weekend running club or maybe an idiosyncratic tour group. It’s only when you get closer that you catch sight of the posters some of them are holding, and see this is a rally opposing Covid-19 restrictions and the prospect of vaccines.

As we mill around, I am drawn towards the familiar outline of Microsoft founder Bill Gates, who adorns a poster just to my right, alongside a sinister-looking image of a vaccine. Gates’s eyes are wild and blood spurts from the syringe he’s holding. In the past few months, Gates has become the bogeyman for the Covid-19 conspiracy movement, and at rallies like this he’s a prominent feature on several posters.

Folklore professor Timothy Tangherlini, who has looked into the link between witchcraft folk tales and these conspiratorial ideologies, describes Gates as a ‘great villain’ for the anti-vaccine movement.5 After all, Gates has huge influence across the world in both technology and health. He’s not just the founder of one of the biggest technology corporations in the world – although he’s no longer Microsoft’s owner – he is also the founder of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a multinational charitable organization that focuses predominantly on healthcare and poverty. Power and money – especially when an individual is not elected or easily held accountable – often leads to valid questions. But this goes far beyond questions about, for example, Gates’s approach to some of the pharmaceutical companies and their decisions around vaccine patents. The extreme claims at the heart of Conspiracyland undermine reasonable discussion.

In Brighton it isn’t just Gates’s face on display. There are banners reading ‘Covid is a HOAX’ and referring to the ‘Scamdemic’. They appear alongside more measured criticism of politicians and vaccine passports, but it’s all very much muddled together.

Starting just weeks into the first lockdown, rallies like this became a regular weekend activity. They were initially organized on Facebook by grass-roots groups that sprang up to oppose Covid-19 restrictions. There are a whole mix of them, with different leaders that organize rallies all around the country – from Brighton to Newcastle.

Ostensibly, these groups are about opposing restrictions, but this has quickly snowballed into conspiracy theories about sinister global plots to harm people involving the pandemic. When the major social media sites cracked down on the disinformation – including attempts to organize large events contrary to the health guidance at the time – many of these groups’ members went what you might call ‘underground’. They joined large channels on Telegram, where there just isn’t much moderation (though when I spoke to Telegram they said calls to violence are expressly forbidden on the platform, that moderators proactively patrol public-facing parts of the app and accept user reports in order to remove calls to violence, and that users are encouraged to report calls to violence using the in-app reporting feature). Still, Telegram was where a lot of the logistical planning for this rally happened.

I strike up a conversation with the man holding that Bill Gates poster. I’m here with BBC Panorama, I explain, gesturing towards the team weaving between protesters with a camera. Only minutes ago, they shouted at us to leave. Threats and hostility have been a pretty common response to any mention of the BBC at rallies like this one. It’s for that reason that the politeness some show comes as a surprise.

My chatter with this man – who I’ll call Denis – and his friend is initially relatively mundane. He’s unsure about revealing too much about who he is to me. After all, I work for what he would call the mainstream media, which he doesn’t trust very much. We talk a bit about how he likes to walk with friends in the sunshine, our mutual frustration that life isn’t going to be back to normal for Christmas – and then I start to question the sign. His allegation is that Bill Gates was somehow involved in creating this pandemic, because he plans to depopulate the planet by injecting them with a killer vaccine. Pretty extreme, as the conspiracies go.

I quiz Denis on this. Why would Bill Gates want to do that? How would that benefit him? What would it achieve? Instead of launching into a complex conversation about sinister global cabals and efforts to make obscene amounts of money through genocide, Denis opts for something simpler.

‘You believe all people are good,’ he explains. ‘I believe almost everyone is bad.’

This simple loss of faith in systems, humanity and the people in power comes up over and over again. In my experience, it often underpins belief in these conspiracy theories.

With that, our conversation dwindles to a close and he tells me that I’m far too nice and normal to be working for the BBC.

Although we didn’t chat for long it seems that Denis’s lack of faith in humanity is so deeply held that it’s apparent it didn’t start with Covid-19. The pandemic has just ignited and brought to the fore his deepest fears. But, rather than quelling those worries, these conspiracy theories are exacerbating them.

More than two years later, in April 2023, I find myself at an almost identical rally against the conspiracies these people believe are unfolding. Only, by this time, there are no lockdowns or Covid-19 restrictions in place. I’m also not by the coast in Brighton. Instead, I’m in Devon, in a town called Totnes. I’ve swapped the beach for a pretty square, in this town known for the way it embraces alternative cultures. Its unashamed sense of self was apparent the minute I set foot in it – I’m here for a new podcast, investigating what has happened to the UK’s conspiracy theory movement.

In Totnes I meet a protester who reminds me a lot of Denis. She’s what I imagine the Denis of the future will be like – someone whose views have now taken over their life and reached new extremes. Her name is Natalie, and she’s laying out posters when I spot her. One features a large pair of red eyes – symbolic of how we’re being ‘monitored forever’, as she later tells me. She’s wearing a black cap embroidered with bright white writing that reads ‘WAKE UP DEVON’. It’s the kind of slogan favoured by conspiracy theory movements that believe we are all sheep blindly following those in power, and we have to open our eyes to what’s really going on. It’s also the name of the group she’s part of. There are several that make up the conspiracy theory landscape in this area of the UK. Like two years ago, they organize online – usually on websites and Telegram.

We get chatting. Most of Natalie’s concerns centre around the idea that governments and global organizations are looking to control us. Her greatest worry is measures to limit pollution. She tells me how human-caused climate change is ‘pseudoscience and fraud’ and that the planet is actually cooling down. This isn’t true. When I push back with references to the overwhelming body of scientific evidence that contradicts this, she points to a minority she deems experts who disagree.

I begin to question her sources. That’s often a lot more effective than getting into a debate, because she just doesn’t believe what the evidence points to. She talks about a conspiracy theory newspaper I’m investigating called The Light. Set up in the first year of the pandemic, it has continued to share disinformation about a range of topics, both in its pages and on social media channels – from vaccines to climate change and wars and terror attacks. In its pages and on its Telegram channels, it also shares hate – for example, calls for doctors, politicians and anyone they believe to be complicit in these ‘plots’ to be executed. When I challenge Natalie on that, she begins to tear up. Her voice wobbles.

‘I and others here have spent so much of our time trying to save humanity, trying to wake them up, trying to help them. We’ve lost our families, lost our friends, and we still stand in our truth because we know it is the truth and so… I’m sorry, it’s upsetting me.’

I find myself comforting her. Her emotion has caught me off guard. It’s raw and fearful, I’m struck by just how deeply Natalie believes all of this. She tells me ‘they’ – the allusive powers that be – want not just to ‘control us’ but also to ‘kill us’. While Denis was mainly frustrated at the pandemic, Natalie has been wholly indoctrinated into this world. To believe you and those you love are being targeted in this way is really scary. I ask her about those feelings of fear.

I have heard so many times about the fracturing of relationships and families, but Natalie signals a new extreme. No one has ever burst into tears in front of me at any of these protests before, and Natalie seems so genuinely convinced of everything she’s told me about that she’s genuinely frightened. She can’t seem to see the misinformation and hate she’s being fed.

Moments later, Natalie is embedded in the procession that’s heading off from the square. She clutches a megaphone and chants. Her warnings about these sinister plots hang heavy in the spring air.

* * * *

Both Denis and Natalie got to the heart of two important questions for me.

The first – why don’t I believe in online conspiracies? There are multiple reasons for my lack of belief, but at the heart of it is a simple answer: trust. I have faith in a system and institutions that have not on the whole let me down, plus a doctor for a dad and a mum who was once a nurse. Both of them would certainly refuse to follow orders from a sinister overlord – contrary to what a lot of these protesters frequently suggested around the pandemic.

That leaves me far less vulnerable to online disinformation. Research tells us that those drawn to pseudoscience and conspiracy theories tend to lean away from rational fact and into spirituality.6 That’s to say, they are much less likely to rely on the evidence available and the experts who are sharing it. I’ve tended to find that’s because their personal experience has led them to doubt those who the rest of us are more likely to believe – including doctors, scientists and professors. Maybe they had a bad experience and were let down or misled in some way, or maybe that happened to someone they know. Once you no longer trust the people with the expertise to explain what’s going on, even when the weight of the evidence is in their favour, it becomes very difficult to make sense of what’s happening.

The second question – who really believes this stuff? There’s a realm of misconceptions we have about who becomes drawn into these online conspiracy movements. Stupid, bonkers, lonely – those are just a few of the words I was greeted with when, in the name of research, I asked passers-by on a central London street how they would describe a conspiracy theorist.

Denis, with his Bill Gates poster down by Brighton beach, and Natalie, with her megaphone in the centre of Totnes, are a starting point for countering some of the misguided stereotypes that exist about people like them. They were both engaging and interesting. At the same time they felt let down and exploited, and genuinely thought everyone was bad. The only difference was how deeply they’d become immersed in the world of conspiracy theories. Denis had just begun his descent into Conspiracyland, while Natalie was already engulfed – to the point where she seemed to have severed her connections to some of her family and friends. I don’t think either of them were stupid or nasty. I think they both cared a lot about people, and they were hyper-curious. They both seemed to be looking for a sense of control in a chaotic world.

My impression of the true believers is backed up by studies too, which suggest people are sucked in by conspiracy theories when ‘important psychological needs are not being met’.7 Dr Karen Douglas talks about three different types of needs. There’s the epistemic, which include ‘the desire to satisfy curiosity and avoid uncertainty’ – looking for patterns even when they don’t exist. There’s also a sense of existential threat. This involves attempting to restore a ‘threatened sense of scrutiny and control’ and regain power. For the true believers, it can be about a feeling of agency when they feel that is otherwise lacking. The third need is social8 – again, relevant to both of these protesters. Even during our brief conversations, it was apparent to me that they both felt like they belonged, and to a group of which they were proud to be a member.

Heightened worry pushes people to seek out certain answers. Now, with social media at your fingertips, it’s possible to do that and find yourself connected to a community like this – and the ideas they promote – quicker than ever before. The land of social media is not an easy one to navigate, and huge volumes of information – and misinformation – come from all sides.

* * * *

Though meeting them was instructive in some ways, both Denis and Natalie remained somewhat two-dimensional to me. These were fleeting conversations at chaotic rallies. But there are other people whose stories I’ve investigated in recent years, and they can help to deepen our understanding of who the true believers really are.

The first is a man named Gary Matthews, who died from Covid-19 in January 2021 at the age of forty-six, despite believing the pandemic wasn’t real.

I first saw Gary in a photograph displayed at the top of a news site. I remember links to the article appearing all over my social media feeds, accompanied by stark warnings. Posts exclaimed how this was a reminder of the dangers of pseudoscience. Chatting to my editor at the time, though, we realized that the coverage raised more questions than it answered.

I started to read about who this man was. The image painted of him by different people seemed at odds – in the press, on Facebook pages, in the form of tributes from friends. At times he was painted as crazy, an idiot who should have known better. In other pieces, he was depicted as a sad and troubled man who had blindly followed the bad guys – or as a martyr for the Covid-19 conspiracy movement. Occasionally, people spoke about his sensitivity and artistic talent, but empathy seemed to be scarce. I wanted to understand who Gary really was, how he’d come to believe what he did, and how it had affected his actions.

Gary lived in Shrewsbury, a pretty market town in the UK. As I would discover from speaking to friends and family members, he loved art. He opposed war. He was a gentle man. He was loved deeply by those close to him. Gary did not fit the ‘mad and stupid’ stereotype often associated with conspiracy theorists.

Yet he did seem to believe much of the disinformation around the pandemic, according to those who knew him best. I turned to two of Gary’s friends, Peter and Geoff, to understand why and how he came to believe what he did.

Peter and Geoff’s beautiful old townhouse was located near the river in Shrewsbury. In the December sunshine in 2020, the river glistened. It almost felt like the house was floating. Inside, their ornate living room was decorated with trinkets from a life well lived. There was a certain peace that had settled over this home. Peter and Geoff told me how this was where Gary had sought solace as a young man trying to make sense of his place in the world. I could immediately see why Gary had spent so much time here.

Ardent protesters and champions of LGBTQ rights, Peter and Geoff had created a space where you could be whoever you wanted to be. That had attracted Gary, and he had been a fierce advocate for political causes. It was the Socialist Worker that had initially bonded the three of them. Gary would pop round to deliver the paper and come in for a cup of tea.

When Peter and Geoff first met Gary, he was fresh-faced – and a little bit broken. They gathered that life as a teenager had been hard for him, with bullying and taunting, accusations that he was gay, and repeated reminders that he didn’t fit in. He relished the opportunity to become closer to the couple and the other people they took under their wing. There was a freedom to be who you wanted in their circle. The constraints and expectations Gary had grown up with dissolved to some extent.

‘The thing about Gary is he knew who he wasn’t. But he wasn’t quite sure what he was or who he was,’ Geoff told me. His shoulders sagged as he recalled the young man who had walked through their door what felt like many moons ago.

Soon, it was more than just weekly cups of tea. Gary spent time living with the couple when he fell ill with cancer in his twenties. Together, they got Gary back on his feet. But once he was better, regular catch-ups and conversations about politics started to change. Gary’s advocacy and campaigning started to venture beyond advocating for LGBTQ rights and equality.

The Syrian civil war – which broke out in 2011 between the Syrian Arab Republic, led by President Bashar al-Assad, and opposition forces and groups – became a real worry for Gary. Peter and Geoff described to me how Gary hated war and feared for the people caught up in it. But, as Gary sought out more information about the conflict, he soon found himself exposed to disinformation online, often propagated by those who supported the Syrian regime. I’ve seen some of this propaganda, and it’s easy to understand how emotive posts could draw in someone like Gary, who was advocating for peace. It was then that his conspiratorial worldview started to take shape.

‘My view was that Assad was just doing the most appalling things to the population,’ Peter told me, laying out some of the evidence he’d seen of what was actually happening. But the social media lens through which Gary was beginning to experience world events told him otherwise. Conspiracy theories had started to spread like wildfire, with the help of the Russian state propaganda machine after they entered the war in support of Assad.

‘Gary was saying, “Well, no, actually, this is not true. Assad is not so bad.” He was just so… He had changed a bit, he was very convinced and almost slightly insulting: “You’re being brainwashed. Can’t you see?”’ Peter explained.

Both Peter and Geoff said attempts to challenge those beliefs and confront Gary with other evidence became futile. Geoff described conversations where there was no room for debate. It seemed to me that it had become a lot less about the ins and outs of what Gary thought was really happening in Syria, and a lot more about his belief that the mainstream media and politicians were lying about it. That led him to believe whatever was in opposition to what they were saying, even when the evidence suggested otherwise. This was the latest part of Gary’s search to make sense of the world and everything that happened in it.

Gary was always drawn towards ‘cultish groups’, Geoff recalled. He wanted to feel a part of something that also helped him better understand the world; and becoming involved with the disinformation around Syria was a means of doing that. He thought life was unfair and laid the blame simply and squarely at what he saw as the mainstream media and the untrue narratives they peddled.

What had once been about challenging the people in power in the way that Geoff and Peter had done throughout their lives just became too simplified, until everything was actually part of a plot to harm the average person in Syria or the UK. Gary stopped challenging the powerful people involved in those wars, even when there was evidence of their wrongdoing. It seemed he stopped being able to see the nuance and complexities.

At the time – and this is still the case now – I struggled to square the circle. Gary was loved and accepted by his family and the friends around him. He was clever, creative, loving – and yet felt like he just didn’t fit. Head in the clouds, seeking a purpose first through painting, photography and art, and then through something more – these conspiracy theory circles. They were like a drug that immediately offered the agency, connection and fulfilment he had been craving.

Geoff explained to me that ‘the scar was so deep’ when it came to Gary. This craving for meaning was one he’d had his whole life. He was enraged by injustice and wanted to stick up for others who were maligned or suffering.

As the pandemic approached, Gary was vulnerable to the slew of conspiracy theories claiming that this terrifying event was part of a plot to limit our freedoms. Lockdown pushed him closer towards his social media feeds and further away from real people. He became glued to the online world as he sat for hours on end at home on his own. One relative recalled that he seemed ‘possessed’ by the idea that the pandemic was a conspiracy and that it didn’t exist.

I never had the chance to meet Gary, but I turned to his social media profiles for clues. On 15 December 2020, just weeks before he died, he’d liked a tweet proclaiming ‘fresh air’ and the ‘immune system’ as all that was needed to combat the virus. In the end, Gary showed that this wasn’t the case. He contracted Covid-19 and died at home, seemingly without seeking medical assistance.

Gary’s social media footprint, along with testimony from friends and family, became a way to understand how he had become immersed in Covid-19 conspiracy theories in particular. For him, the bad information had started in a Facebook group called the Shropshire Corona Resilience Network. I got a sense of their beliefs by looking at a new version of the group set up after Gary died.

One post showed a wanted poster with a picture of then UK health minister Matt Hancock – accusing him of committing ‘genocide by vaccine’. Another long post described how the virus was ‘100 percent a dark magic ritual’. These weren’t exactly legitimate political debates about, say, the impact of lockdown measures, or the viability of vaccine passports.

Links on that group led Gary to various conspiracy influencers with growing followings – and mainstream commentators flirting with the conspiratorial. They populated Twitter (now renamed X), Facebook and Instagram – and of course Telegram, the social media app whose membership was growing rapidly as the pandemic dragged on.

Geoff and Peter remembered watching Gary’s Facebook feed shift before their eyes. When he began sharing specific posts denying the pandemic, while they sat bored and scared at home, they just found it too difficult to communicate with him anymore. They stopped talking to him or looking at his feeds.

But while they might have stopped encountering his posts online, they did bump into him on occasion during the Covid-19 lockdowns. One of the last times was out and about in Shrewsbury. Gary was with his mum, who Geoff and Peter said diligently wore a face mask, while Gary’s face was bare.

When they found out Gary had died from Covid-19 not long after that last encounter, they were both so upset and angry. ‘It didn’t have to happen. And yet it [did],’ said Geoff.

When I interview people who believe these conspiracy theories, I often think about how stressful it must be to think that almost everyone is part of an elite cabal. But I didn’t ever get the chance to ask Gary how it made him feel.

Peter and Geoff gave me the impression that, while Gary derived purpose and community from this world, he did find it terrifying – a bit like Natalie from the protest in Totnes. But they saw him far less in the period when he truly became immersed in the Covid-19 conspiracy theory movement. To figure out what he was thinking and feeling then, I turned to a different friend – who saw him fairly often during the lockdowns.

His name was Adam. He used to meet Gary for walks during the pandemic at the Quarry, an extensive parkland in Shrewsbury. As they wandered around, Gary would talk about his deep fears for the future of humanity. He seemed anxious, frustrated and tortured.

I met Adam on a freezing cold day in that same Quarry. We sat on a bench close to where he had last seen Gary, and Adam told me how they used to paint together and discuss ideas. Kindred spirits in some ways, but different in other respects.

‘This wasn’t somebody with tinfoil on [his] head. This was a very intelligent chap,’ Adam explained, casting his eyes over the river and the frosty pastures of the park. ‘He’s a beautiful man. I mean, he was very gentle, and very delicate. You know, he was kind of pure. There’s very few pure people.’ Adam was still struggling to talk about his friend in the past tense, having only lost him a year earlier.

That conversation with Adam was a reminder of the profound impact this all has. On the lives of those drawn into online conspiracy claims – and on the lives of those left behind. Adam’s grief hung between us.

Adam gave me the impression that he shared with Gary a certain suspicion of authority and the systems that had somewhat let him down. I could tell he’d carefully considered whether to speak to me. He also shared Gary’s dream-like view of the world. Together, they would talk about a world free of conflict, evil and war. They cared deeply about injustice and poverty. But Adam saw the difference between political criticism, concern and suspicion and the outlandish conspiracies that Gary had struggled with.

In Adam’s view, it was the lockdown restrictions that truly pushed Gary into conspiracy theories. Gary was stuck at home in a small flat with too much time on his hands. The places he’d found fulfilment before – like his artwork – disappeared. He started to spend hours and hours online, where he sought out meaning and community.

Adam noted that there were social factors at play here too. In the big houses just down the road from where Gary lived, people often had home offices or gardens. Lockdown wasn’t so hard for them, and so they were less likely to turn to social media to make sense of how uniquely awful their own lives had become.

Those who believe conspiracy theories can also be wealthy, however; many I’ve interviewed are. It’s also important to state that some of the fiercest opponents to conspiracy theorists are people who are not wealthy at all. But Adam said that for Gary, this inequality was important. Gary believed he was being wronged, and that others without the means to make lockdowns comfortable were too. It wasn’t just about the unfair circumstances; it further fuelled his belief that this was somehow part of a plot by the powerful to control or harm the powerless. There are others I’ve interviewed since who struggled to make ends meet during the cost-of-living crisis, and who were spurred deeper into the world of conspiracy theories by the inequality they experienced. It fuels distrust in authority.

‘You have this disparity,’ Adam explained to me, ‘and I suppose in a place like Shrewsbury it’s more evident. It’s quite small, but the affluence is evident, and the lack of it is obviously very demonstrably obvious.’

No attempts to challenge Gary worked. As much as Adam would indulge legitimate questions about lockdown measures and their proportionality, he couldn’t seem to get Gary to see that it didn’t mean the conspiracies about the government creating the pandemic to control our lives were true.

Adam described the ‘off’ feeling he’d sensed when he and Gary last chatted. It wasn’t long before Gary died. He put it down to the toll of restrictions, or Gary starting to feel ill. He’d never see Gary again. When I spoke to him, he was unsurprisingly still finding it very hard to process that he couldn’t speak to his friend anymore. ‘You just assume that this will pass, and he’ll be around the corner in a minute and this will just go away.’

Adam couldn’t fill in the gaps for me about those last few weeks of Gary’s life, but there were others who could. His immediate family weren’t able to talk to me directly, but were happy for his cousins to share more information about what happened. Gary’s cousin Tristan talked me through what the family knew about his last moments, and shared conversations he’d had with Gary’s close family.