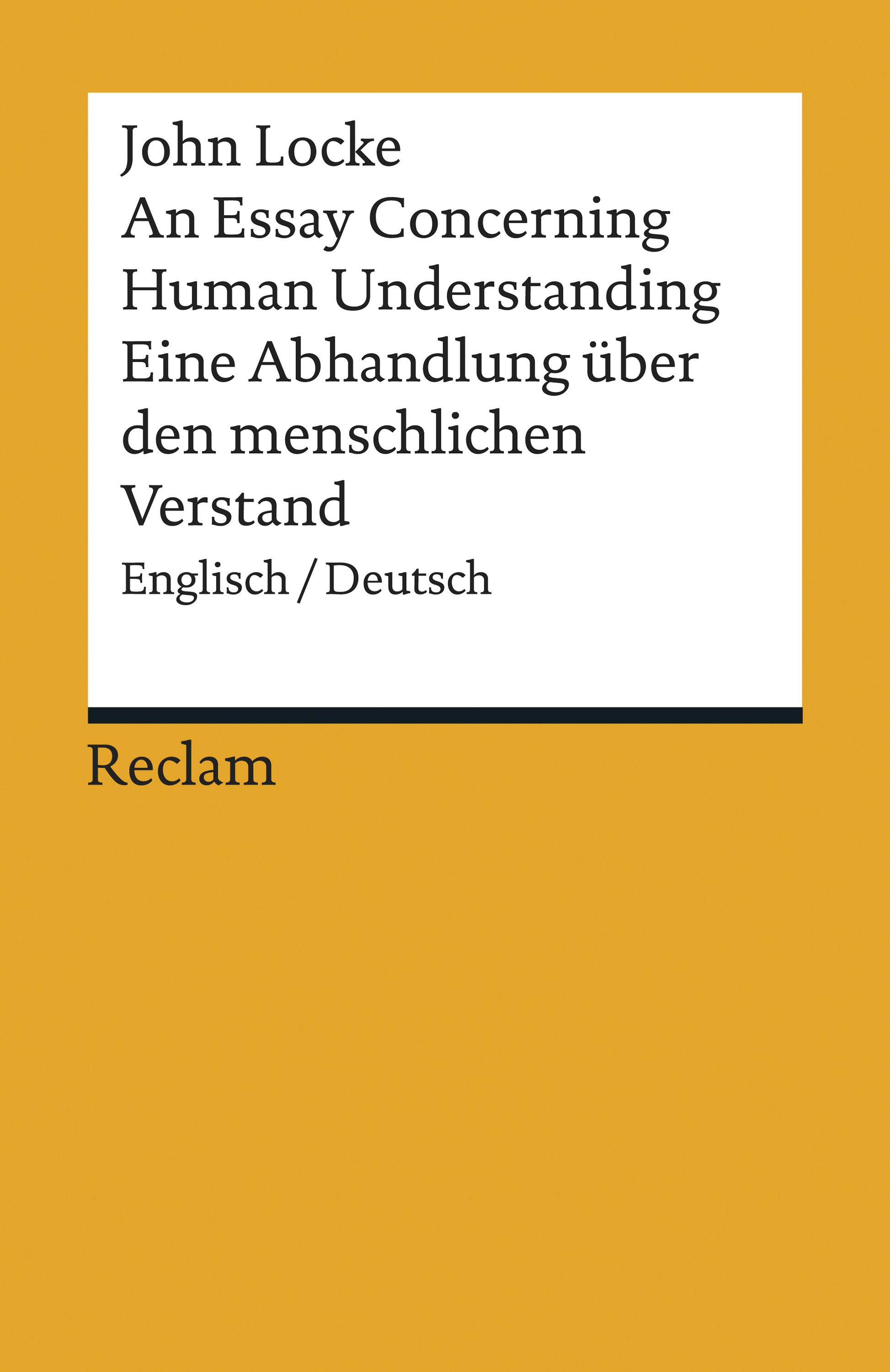

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding / Ein Versuch über den menschlichen Verstand. Auswahlausgabe E-Book

John Locke

14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reclam Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Reclams Universal-Bibliothek

- Sprache: Deutsch

Locke unternimmt in seinem 1689 erschienenen Werk den Versuch einer Kritik der menschlichen Erkenntnisfähigkeiten überhaupt. Der Essay ist zwar damit eines der wichtigsten philosophischen Bücher der Neuzeit, doch allein sein Umfang wirkt einschüchternd. Diese Auswahlausgabe macht den Text jetzt in einer neuen Übersetzung zugänglich (die letzte Übersetzung datiert aus dem Jahre 1911), indem sie ihn um etwa zwei Drittel kürzt, dabei am originalen Wortlaut nichts ändert und ihn auch nicht in thematischer Hinsicht verengt. Ein an modernen Erfordernissen orientierter Kommentar, ein entsprechendes Nachwort sowie ein Begriffsregister runden die Ausgabe ab. E-Book mit Seitenzählung der gedruckten Ausgabe: Buch und E-Book können parallel benutzt werden.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 986

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

John Locke

An Essay Concerning Human UnderstandingEin Versuch über den menschlichen Verstand

Englisch / DeutschAuswahlausgabe

Übersetzt von Joachim SchulteHerausgegeben von Katia Saporiti

Reclam

2020 Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag GmbH, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen

Gesamtherstellung: Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag GmbH, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen

Made in Germany 2020

RECLAM ist eine eingetragene Marke der Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart

ISBN 978-3-15-961550-9

ISBN der Buchausgabe 978-3-15-019501-7

www.reclam.de

Inhalt

[5]An Essay Concerning Human UnderstandingEin Versuch über den menschlichen Verstand

[6]The Epistle to the Reader

Reader,

I Here put into thy Hands, what has been the diversion of some of my idle and heavy Hours: If it has the good luck to prove so of any of thine, and thou hast but half so much Pleasure in reading, as I had in writing it, thou wilt as little think thy Money, as I do my Pains, ill bestowed. […]

[…]

[…] Were it fit to trouble thee with the History of this Essay, I should tell thee that five or six Friends meeting at my Chamber, and discoursing on a Subject very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the Difficulties that rose on every side. After we had a while puzzled our selves, without coming any nearer a Resolution of those Doubts which perplexed us, it came into my Thoughts, that we took a wrong course; and that, before we set our selves upon Enquiries of that Nature, it was necessary to examine our own Abilities, and see, what Objects our Understandings were, or were not fitted to deal with. This I proposed to the Company, who all readily assented; and thereupon it was agreed, that this should be our first Enquiry. Some hasty and undigested Thoughts, on a Subject I had never before considered, which I set down against our next Meeting, gave the first entrance into this Discourse, which having been thus begun by Chance, was continued by Intreaty; written by incoherent parcels; and, after long intervals of neglect, resum’d again, as my Humour or Occasions permitted; and at last, in a retirement, where an [8]Attendance on my Health gave me leisure, it was brought into that order, thou now seest it.

This discontinued way of writing may have occasioned, besides others, two contrary Faults, viz. that too little, and too much may be said in it. If thou findest any thing wanting, I shall be glad, that what I have writ, gives thee any Desire, that I should have gone farther: If it seems too much to thee, thou must blame the Subject; for when I first put Pen to Paper, I thought all I should have to say on this Matter, would have been contained in one sheet of Paper; but the farther I went, the larger Prospect I had: New Discoveries led me still on, and so it grew insensibly to the bulk it now appears in. I will not deny, but possibly it might be reduced to a narrower compass than it is; and that some Parts of it might be contracted; the way it has been writ in, by catches, and many long intervals of Interruption, being apt to cause some Repetitions. […]

[…]

[…] The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an Age that produces such Masters, as the Great Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some others of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing the Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge; which certainly had been very much more advanced in the World, if the Endeavours of ingenious and industrious Men had not been much cumbred with the learned [10]but frivolous use of uncouth, affected, or unintelligible Terms, introduced into the Sciences, and there made an Art of, to that Degree, that Philosophy, which is nothing but the true Knowledge of Things, was thought unfit, or uncapable to be brought into well-bred Company, and polite Conversation. Vague and insignificant Forms of Speech, and Abuse of Language, have so long passed for Mysteries of Science; And hard or misapply’d Words, with little or no meaning, have, by Prescription, such a Right to be mistaken for deep Learning, and heighth of Speculation, that it will not be easie to persuade, either those who speak, or those who hear them, that they are but the Covers of Ignorance, and hindrance of true Knowledge. […]

[…]

The Booksellers preparing for the fourth Edition of my Essay, gave me notice of it, that I might, if I had leisure, make any additions or alterations I should think fit. Whereupon I thought it convenient to advertise the Reader, that besides several corrections I had made here and there, there was one alteration which it was necessary to mention, because it ran through the whole Book, and is of consequence to be rightly understood. What I thereupon said, was this:

Clear and distinct Ideas are terms, which though familiar and frequent in Men’s Mouths, I have reason to think every one, who uses, does not perfectly understand. And possibly ’tis but here and there one, who gives himself the trouble to consider them so far as to know what he himself, or others precisely mean by them; I have therefore in most places chose to put determinate or determined, instead of clear and distinct, as more [12]likely to direct Men’s thoughts to my meaning in this matter. By those denominations, I mean some object in the Mind, and consequently determined, i. e. such as it is there seen and perceived to be. This I think may fitly be called a determinate or determin’d Idea, when such as it is at any time objectively in the Mind, and so determined there, it is annex’d, and without variation determined to a name or articulate sound, which is to be steadily the sign of that very same object of the Mind, or determinate Idea.

To explain this a little more particularly. By determinate, when applied to a simple Idea, I mean that simple appearance, which the Mind has in its view, or perceives in it self, when that Idea is said to be in it: By determined, when applied to a complex Idea, I mean such an one as consists of a determinate number of certain simple or less complex Ideas, joyn’d in such a proportion and situation, as the Mind has before its view, and sees in it self when that Idea is present in it, or should be present in it, when a Man gives a name to it. I say should be; because it is not every one, nor perhaps any one, who is so careful of his Language, as to use no Word, till he views in his Mind the precise determined Idea, which he resolves to make it the sign of. The want of this is the cause of no small obscurity and confusion in Men’s thoughts and discourses.

I know there are not Words enough in any Language to answer all the variety of Ideas, that enter into Men’s discourses [14]and reasonings. But this hinders not, but that when any one uses any term, he may have in his Mind a determined Idea, which he makes it the sign of, and to which he should keep it steadily annex’d during that present discourse. Where he does not, or cannot do this, he in vain pretends to clear or distinct Ideas: ’Tis plain his are not so: and therefore there can be expected nothing but obscurity and confusion, where such terms are made use of, which have not such a precise determination.

[…]

[16]Book I

CHAPTER I

Introduction

§ 1. SINCE it is the Understanding that sets Man above the rest of sensible Beings, and gives him all the Advantage and Dominion, which he has over them; it is certainly a Subject, even for its Nobleness, worth our Labour to enquire into. The Understanding, like the Eye, whilst it makes us see, and perceive all other Things, takes no notice of it self: And it requires Art and Pains to set it at a distance, and make it its own Object. But whatever be the Difficulties, that lie in the way of this Enquiry; whatever it be, that keeps us so much in the Dark to our selves; sure I am, that all the Light we can let in upon our Minds; all the Acquaintance we can make with our own Understandings, will not only be very pleasant; but bring us great Advantage, in directing our Thoughts in the search of other Things.

§ 2. This, therefore, being my Purpose to enquire into the Original, Certainty, and Extent of humane Knowledge; together, with the Grounds and Degrees of Belief, Opinion, and Assent; I shall not at present meddle with the Physical Consideration of the Mind; or trouble my self to examine, wherein its Essence consists, or by what Motions of our Spirits, or Alterations of our Bodies, we come to have any Sensation by our Organs, or any Ideas in our Understandings; and whether those [18]Ideas do in their Formation, any, or all of them, depend on Matter, or no. These are Speculations, which, however curious and entertaining, I shall decline, as lying out of my Way, in the Design I am now upon. It shall suffice to my present Purpose, to consider the discerning Faculties of a Man, as they are employ’d about the Objects, which they have to do with: and I shall imagine I have not wholly misemploy’d my self in the Thoughts I shall have on this Occasion, if, in this Historical, plain Method, I can give any Account of the Ways, whereby our Understandings come to attain those Notions of Things we have, and can set down any Measures of the Certainty of our Knowledge, or the Grounds of those Perswasions, which are to be found amongst Men […].

§ 3. It is […] worth while, to search out the Bounds between Opinion and Knowledge; and examine by what Measures, in things, whereof we have no certain Knowledge, we ought to regulate our Assent, and moderate our Perswasions. In Order whereunto, I shall pursue this following Method.

First, I shall enquire into the Original of those Ideas, Notions, or whatever else you please to call them, which a Man observes, and is conscious to himself he has in his Mind; and the ways whereby the Understanding comes to be furnished with them.

Secondly, I shall endeavour to shew what Knowledge the Understanding hath by those Ideas; and the Certainty, Evidence, and Extent of it.

Thirdly, I shall make some Enquiry into the Nature and Grounds of Faith, or Opinion: whereby I mean that Assent, which we give to any Proposition as true, of whose Truth yet [20]we have no certain Knowledge: And here we shall have Occasion to examine the Reasons and Degrees of Assent.

§ 4. If by this Enquiry into the Nature of the Understanding, I can discover the Powers thereof; how far they reach; to what things they are in any Degree proportionate; and where they fail us, I suppose it may be of use to prevail with the busy Mind of Man, to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its Comprehension; to stop, when it is at the utmost Extent of its Tether; and to sit down in a quiet Ignorance of those Things, which, upon Examination, are found to be beyond the reach of our Capacities. […]

§ 5. For though the Comprehension of our Understandings, comes exceeding short of the vast Extent of Things; yet, we shall have Cause enough to magnify the bountiful Author of our Being, for that Portion and Degree of Knowledge, he has bestowed on us, so far above all the rest of the Inhabitants of this our Mansion. Men have Reason to be well satisfied with what God hath thought fit for them, since he hath given them (as St. Peter says) πάντα πρὸς ζωὴν καὶ εὐσέβειαν, Whatsoever is necessary for the Conveniences of Life, and Information of Vertue; and has put within the reach of their Discovery the comfortable Provision for this Life and the Way that leads to a better. […]

§ 6. When we know our own Strength, we shall the better know what to undertake with hopes of Success: And when we have well survey’d the Powers of our own Minds, and made some Estimate what we may expect from them, we shall not be inclined either to sit still, and not set our Thoughts on work at [22]all, in Despair of knowing any thing; nor on the other side question every thing, and disclaim all Knowledge, because some Things are not to be understood. ’Tis of great use to the Sailor to know the length of his Line, though he cannot with it fathom all the depths of the Ocean. ’Tis well he knows, that it is long enough to reach the bottom, at such Places, as are necessary to direct his Voyage, and caution him against running upon Shoals, that may ruin him. Our Business here is not to know all things, but those which concern our Conduct. If we can find out those Measures, whereby a rational Creature put in that State, which Man is in, in this World, may, and ought to govern his Opinions, and Actions depending thereon, we need not to be troubled, that some other things escape our Knowledge.

[…]

§ 8. […] Before I proceed on to what I have thought on this Subject, I must here in the Entrance beg pardon of my Reader, for the frequent use of the word Idea, which he will find in the following Treatise. It being that Term, which, I think, serves best to stand for whatsoever is the Object of the Understanding when a Man thinks, I have used it to express whatever is meant by Phantasm, Notion, Species, or whatever it is, which the Mind can be employ’d about in thinking; and I could not avoid frequently using it.

I presume it will be easily granted me, that there are such Ideas in Men’s Minds; every one is conscious of them in [24]himself, and Men’s Words and Actions will satisfy him, that they are in others.

Our first Enquiry then shall be, how they come into the Mind.

CHAPTER II

No innate Principles in the Mind

§ 1. It is an established Opinion amongst some Men, That there are in the Understanding certain innate Principles; some primary Notions (Κοιναὶ ἔννοιαι), Characters, as it were stamped upon the Mind of Man, which the Soul receives in its very first Being; and brings into the World with it. It would be sufficient to convince unprejudiced Readers of the falseness of this Supposition, if I should only shew (as I hope I shall in the following Parts of this Discourse) how Men, barely by the Use of their natural Faculties, may attain to all the Knowledge they have, without the help of any innate Impressions; and may arrive at Certainty, without any such Original Notions or Principles. For I imagine any one will easily grant, That it would be impertinent to suppose, the Ideas of Colours innate in a Creature, to whom God hath given Sight, and a Power to receive them by the Eyes from external Objects: and no less unreasonable would it be to attribute several Truths, to the Impressions of Nature, and innate Characters, when we may observe in our selves Faculties, fit to attain as easy and certain Knowledge of them, as if they were Originally imprinted on the Mind.

But because a Man is not permitted without Censure to follow his own Thoughts in the search of Truth, when they lead [26]him ever so little out of the common Road: I shall set down the Reasons, that made me doubt of the Truth of that Opinion […].

§ 2. There is nothing more commonly taken for granted, than that there are certain Principles both Speculative and Practical (for they speak of both) universally agreed upon by all Mankind: which therefore they argue, must needs be the constant Impressions, which the Souls of Men receive in their first Beings, and which they bring into the World with them, as necessarily and really as they do any of their inherent Faculties.

§ 3. This Argument, drawn from Universal Consent, has this Misfortune in it, That if it were true in matter of Fact, that there were certain Truths, wherein all Mankind agreed, it would not prove them innate, if there can be any other way shewn, how Men may come to that Universal Agreement, in the things they do consent in; which I presume may be done.

§ 4. But, which is worse, this Argument of Universal Consent, which is made use of, to prove innate Principles, seems to me a Demonstration that there are none such: Because there are none to which all Mankind give an Universal Assent. I shall begin with the Speculative, and instance in those magnified Principles of Demonstration, Whatsoever is, is; and ’Tis impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be, which of all others I think have the most allow’d Title to innate. These have so setled a Reputation of Maxims universally received, that ’twill, no doubt, be thought strange, if any one should seem to question it. But yet I take liberty to say, That these Propositions are [28]so far from having an universal Assent, that there are a great Part of Mankind, to whom they are not so much as known.

§ 5. For, first ’tis evident, that all Children, and Ideots, have not the least Apprehension or Thought of them: and the want of that is enough to destroy that universal Assent, which must needs be the necessary concomitant of all innate Truths: it seeming to me near a Contradiction, to say, that there are Truths imprinted on the Soul, which it perceives or understands not; imprinting, if it signify any thing, being nothing else, but the making certain Truths to be perceived. For to imprint any thing on the Mind without the Mind’s perceiving it, seems to me hardly intelligible. If therefore Children and Ideots have Souls, have Minds, with those Impressions upon them, they must unavoidably perceive them, and necessarily know and assent to these Truths, which since they do not, it is evident that there are no such Impressions. For if they are not Notions naturally imprinted, How can they be innate? And if they are Notions imprinted, How can they be unknown? To say a Notion is imprinted on the Mind, and yet at the same time to say, that the mind is ignorant of it, and never yet took notice of it, is to make this Impression nothing. No Proposition can be said to be in the Mind, which it never yet knew, which it was never yet conscious of. For if any one may; then, by the same Reason, all Propositions that are true, and the Mind is capable ever of assenting to, may be said to be in the Mind, and to be imprinted: Since if any one can be said to be in [30]the Mind, which it never yet knew, it must be only because it is capable of knowing it; and so the Mind is of all Truths it ever shall know. Nay, thus Truths may be imprinted on the Mind, which it never did, nor ever shall know: for a Man may live long, and die at last in Ignorance of many Truths, which his Mind was capable of knowing, and that with Certainty. So that if the Capacity of knowing be the natural Impression contended for, all the Truths a Man ever comes to know, will, by this Account, be, every one of them, innate; and this great Point will amount to no more, but only to a very improper way of speaking; which whilst it pretends to assert the contrary, says nothing different from those, who deny innate Principles. For no Body, I think, ever denied, that the Mind was capable of knowing several Truths. The Capacity, they say, is innate, the Knowledge acquired. But then to what end such contest for certain innate Maxims? If Truths can be imprinted on the Understanding without being perceived, I can see no difference there can be, between any Truths the Mind is capable of knowing in respect of their Original: They must all be innate, or all adventitious: In vain shall a Man go about to distinguish them. He therefore that talks of innate Notions in the Understanding, cannot (if he intend thereby any distinct sort of Truths) mean such Truths to be in the Understanding, as it never perceived, and is yet wholly ignorant of. For if these Words (to be in the Understanding) have any Propriety, they signify to be understood. So that, to be in the Understanding, and, not to be understood; to be in the Mind, and, never to be perceived, is all [32]one, as to say, any thing is, and is not, in the Mind or Understanding. If therefore these two Propositions, Whatsoever is, is; and, It is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be, are by Nature imprinted, Children cannot be ignorant of them: Infants, and all that have Souls must necessarily have them in their Understandings, know the Truth of them, and assent to it.

§ 6. To avoid this, ’tis usually answered, that all Men know and assent to them, when they come to the use of Reason, and this is enough to prove them innate […].

§ 7. […] to apply this Answer with any tolerable Sence to our present Purpose, it must signify one of these two things; either, That as soon as Men come to the use of Reason, these supposed native Inscriptions come to be known, and observed by them: Or else, that the Use and Exercise of Men’s Reason assists them in the Discovery of these Principles, and certainly makes them known to them.

§ 8. If they mean that by the Use of Reason Men may discover these Principles; and that this is sufficient to prove them innate; their way of arguing will stand thus, (viz.) That, whatever Truths Reason can certainly discover to us, and make us firmly assent to, those are all naturally imprinted on the Mind; since that universal Assent, which is made the Mark of them, amounts to no more but this; That by the use of Reason, we are [34]capable to come to a certain Knowledge of, and assent to them; and by this Means there will be no difference between the Maxims of the Mathematicians, and Theorems they deduce from them: All must be equally allow’d innate, they being all Discoveries made by the use of Reason, and Truths that a rational Creature may certainly come to know, if he apply his Thoughts rightly that Way.

§ 9. But how can these Men think the Use of Reason necessary to discover Principles that are supposed innate, when Reason (if we may believe them) is nothing else, but the Faculty of deducing unknown Truths from Principles or Propositions, that are already known? That certainly can never be thought innate, which we have need of Reason to discover, unless as I have said, we will have all the certain Truths, that Reason ever teaches us, to be innate. […]

§ 10. ’Twill here perhaps be said, That Mathematical Demonstrations, and other Truths, that are not innate, are not assented to, as soon as propos’d, wherein they are distinguish’d from these Maxims, and other innate Truths. I shall have occasion to speak of Assent upon the first proposing, more particularly by and by. I shall here only, and that very readily, allow, That these Maxims, and Mathematical Demonstrations are in this different; That the one has need of Reason using of Proofs, to make them out, and to gain our Assent; but the other, as soon as understood, are, without any the least reasoning, embraced and assented to. But I withal beg leave to observe, That [36]it lays open the Weakness of this Subterfuge, which requires the Use of Reason for the Discovery of these general Truths: Since it must be confessed, that in their Discovery there is no Use made of reasoning at all. And I think those who give this Answer, will not be forward to affirm, That the Knowledge of this Maxim, That it is impossible for same thing to be, and not to be, is a deduction of our Reason. […]

[…]

§ 12. If by knowing and assenting to them, when we come to the use of Reason be meant, that this is the time, when they come to be taken notice of by the Mind; and that as soon as Children come to the use of Reason, they come also to know and assent to these Maxims; this also is false, and frivolous. First, It is false. Because it is evident, these Maxims are not in the Mind so early as the use of Reason: and therefore the coming to the use of Reason is falsly assigned, as the time of their Discovery. How many instances of the use of Reason may we observe in Children, a long time before they have any Knowledge of this Maxim, That it is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be? and a great part of illiterate People, and Savages, pass many Years, even of their rational Age, without ever thinking on this, and the like general Propositions. […]

[…]

§ 14. But, Secondly, were it true, that the precise time of their being known, and assented to, were, when Men come to the Use of Reason; neither would that prove them innate. This way of arguing is as frivolous, as the Supposition of it self is [38]false. For by what kind of Logick will it appear, that any Notion is Originally by Nature imprinted in the Mind in its first Constitution, because it comes first to be observed, and assented to, when a Faculty of the Mind, which has quite a distinct Province, begins to exert it self? […] I agree then with these Men of innate Principles, that there is no Knowledge of these general and self-evident Maxims in the Mind, till it comes to the Exercise of Reason: but I deny that the coming to the use of Reason, is the precise time when they are first taken notice of; and, if that were the precise time, I deny that it would prove them innate. […]

§ 15. The Senses at first let in particular Ideas, and furnish the yet empty Cabinet: And the Mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the Memory, and Names got to them. Afterwards the Mind proceeding farther, abstracts them, and by Degrees learns the use of general Names. In this manner the Mind comes to be furnish’d with Ideas and Language, the Materials about which to exercise its discursive Faculty: And the use of Reason becomes daily more visible, as these Materials, that give it Employment, increase. But though the having of general Ideas, and the use of general Words and Reason usually grow together; yet, I see not, how this any way proves them innate. The Knowledge of some Truths, I confess, is very early in the Mind; but in a way that shews them not to be innate. For, if we will observe, we shall find it still to be about Ideas, not innate, but acquired: It being [40]about those first, which are imprinted by external Things, with which Infants have earliest to do, and which make the most frequent Impressions on their Senses. In Ideas thus got, the Mind discovers, That some agree, and others differ, probably as soon as it has any use of Memory; as soon as it is able, to retain and perceive distinct Ideas. But whether it be then, or no, this is certain, it does so long before it has the use of Words; or comes to that, which we commonly call the use of Reason. For a Child knows as certainly, before it can speak, the difference between the Ideas of Sweet and Bitter (i. e. That Sweet is not Bitter) as it knows afterwards (when it comes to speak) That Worm-wood and Sugar-plumbs, are not the same thing.

[…]

§ 17. This Evasion therefore of general Assent, when Men come to the use of Reason, failing as it does, and leaving no difference between those supposed-innate, and other Truths, that are afterwards acquired and learnt, Men have endeavoured to secure an universal Assent to those they call Maxims, by saying, they are generally assented to, as soon as proposed, and the Terms they are propos’d in, understood […]

§ 18. In Answer to this, I demand whether ready assent, given to a Proposition upon first hearing, and understanding the Terms, be a certain mark of an innate Principle? If it be not, such a general assent is in vain urged as a Proof of them: If it be said, that it is a mark of innate, they must then allow all such Propositions to be innate, which are generally assented to as soon as heard, whereby they will find themselves plentifully [42]stored with innate Principles. For upon the same ground (viz.) of Assent at first hearing and understanding the Terms, That Men would have those Maxims pass for innate, they must also admit several Propositions about Numbers, to be innate: And thus, That One and Two are equal to Three, That Two and Two are equal to Four, and a multitude of other the like Propositions in Numbers, that every Body assents to, at first hearing, and understanding the Terms, must have a place amongst these innate Axioms. Nor is this the Prerogative of Numbers alone, and Propositions made about several of them: But even natural Philosophy, and all the other Sciences afford Propositions, which are sure to meet with Assent, as soon as they are understood. That two Bodies cannot be in the same place, is a Truth, that no Body any more sticks at, than at this Maxim, That it is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be; That White is not Black, That a Square is not a Circle, That Yellowness is not Sweetness: These, and a Million of such other Propositions, as many at least, as we have distinct Ideas, every Man in his Wits, at first hearing, and knowing what the Names stand for, must necessarily assent to. If then these Men will be true to their own Rule, and have Assent at first hearing and understanding the Terms, to be a mark of innate, they must allow, not only as many innate Propositions, as Men have distinct Ideas; but as many as Men can make Propositions, wherein different Ideas are denied one of another. Since every Proposition, wherein one different Idea is denied of another, will as certainly find [44]Assent at first hearing and understanding the Terms, as this general one, It is impossible for the same to be, and not to be; or that which is the Foundation of it, and is the easier understood of the two, The same is not different: By which Account, they will have Legions of innate Propositions of this one sort, without mentioning any other. But since no Proposition can be innate, unless the Ideas, about which it is, be innate, This will be, to suppose all our Ideas of Colours, Sounds, Tastes, Figures, etc. innate; than which there cannot be any thing more opposite to Reason and Experience. Universal and ready assent, upon hearing and understanding the Terms, is (I grant) a mark of self-evidence: but self-evidence, depending not on innate Impressions, but on something else (as we shall shew hereafter) belongs to several Propositions, which no Body was yet so extravagant, as to pretend to be innate.

§ 19. Nor let it be said, That those more particular self-evident Propositions, which are assented to at first hearing, as, That One and Two are equal to Three; That Green is not Red, etc. are received as the Consequences of those more universal Propositions, which are look’d on as innate Principles: since any one, who will but take the Pains to observe what passes in the Understanding, will certainly find, That these, and the like less general Propositions, are certainly known and firmly assented to, by those, who are utterly ignorant of those more general Maxims; and so, being earlier in the Mind than those (as they are called) first Principles, cannot owe to them the Assent, wherewith they are received at first hearing.

[…]

[46]§ 21. But we have not yet done with assenting to Propositions at first hearing and understanding their Terms; ’tis fit we first take notice, That this, instead of being a mark, that they are innate, is a proof of the contrary: Since it supposes, that several, who understand and know other things, are ignorant of these Principles, till they are propos’d to them; and that one may be unacquainted with these Truths, till he hears them from others. For if they were innate, What need they be propos’d, in order to gaining assent; when, by being in the Understanding, by a natural and original Impression (if there were any such) they could not but be known before? […]

§ 22. If it be said, The understanding hath an implicit Knowledge of these Principles, but not an explicit, before this first hearing, (as they must, who will say, That they are in the Understanding before they are known) it will be hard to conceive what is meant by a Principle imprinted on the Understanding Implicitly; unless it be this, That the Mind is capable of understanding and assenting firmly to such Propositions. […]

§ 23. There is I fear this farther weakness in the foregoing Argument, which would perswade us, That therefore those Maxims are to be thought innate, which Men admit at first hearing, because they assent to Propositions, which they are not taught, nor do receive from the force of any Argument or Demonstration, but a bare Explication or Understanding of the Terms. Under which, there seems to me to lie this fallacy; That Men are supposed not to be taught, nor to learn any thing de [48]novo; when in truth, they are taught, and do learn something they were ignorant of before. For first it is evident, that they have learned the Terms and their Signification: neither of which was born with them. But this is not all the acquired Knowledge in the case: The Ideas themselves, about which the Proposition is, are not born with them, no more than their Names, but got afterwards. So, that in all Propositions that are assented to, at first hearing; the Terms of the Proposition, their standing for such Ideas, and the Ideas themselves that they stand for, being neither of them innate, I would fain know what there is remaining in such Propositions, that is innate. […]

§ 24. To conclude this Argument of universal Consent, I agree with these Defenders of innate Principles, That if they are innate, they must needs have universal assent. For that a Truth should be innate, and yet not assented to, is to me as unintelligible, as for a Man to know a Truth, and be ignorant of it at the same time. But then, by these Men’s own Confession, they cannot be innate; since they are not assented to, by those who understand not the Terms, nor by a great part of those who do understand them, but have yet never heard, nor thought of those Propositions; which, I think, is at least one half of Mankind. But were the Number far less, it would be enough to destroy universal assent, and thereby shew these Propositions not to be innate, if Children alone were ignorant of them.

[50][…]

§ 28. […] Upon the whole matter, I cannot see any ground, to think these two famed speculative Maxims innate: since they are not universally assented to; and the assent they so generally find, is no other, than what several Propositions, not allowed to be innate, equally partake in with them: And since the assent that is given them, is produced another way, and comes not from natural Inscription, as I doubt not but to make appear in the following Discourse. And if these first Principles of Knowledge and Science, are found not to be innate, no other speculative Maxims can (I suppose) with better Right pretend to be so.

CHAPTER III

No innate practical Principles

§ 1. IF those speculative Maxims, whereof we discoursed in the fore-going Chapter, have not an actual universal assent from all Mankind, as we there proved, it is much more visible concerning practical Principles, that they come short of an universal Reception: and I think it will be hard to instance any one moral Rule, which can pretend to so general and ready an assent as, What is, is, or to be so manifest a Truth as this, That it is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be. Whereby it is evident, That they are farther removed from a title to be [52]innate; and the doubt of their being native Impressions on the Mind, is stronger against these moral Principles than the other. Not that it brings their Truth at all in question. They are equally true, though not equally evident. Those speculative Maxims carry their own Evidence with them: But moral Principles require Reasoning and Discourse, and some Exercise of the Mind, to discover the certainty of their Truth. They lie not open as natural Characters ingraven on the Mind; which if any such were, they must needs be visible by themselves, and by their own light be certain and known to every Body. But this is no Derogation to their Truth and Certainty, no more than it is to the Truth or Certainty, of the Three Angles of a Triangle being equal to two right ones, because it is not so evident, as The whole is bigger than a part; nor so apt to be assented to at first hearing. It may suffice, that these moral Rules are capable of Demonstration: And therefore it is our own faults, if we come not to a certain Knowledge of them. But the Ignorance wherein many Men are of them, and the slowness of assent, wherewith others receive them, are manifest Proofs, that they are not innate, and such as offer themselves to their view without searching.

§ 2. Whether there be any such moral Principles, wherein all Men do agree, I appeal to any, who have been but moderately conversant in the History of Mankind, and look’d abroad beyond the Smoak of their own Chimneys. Where is that practical Truth, that is universally received without doubt or question, as it must be if innate? Justice, and keeping of Contracts, is that which most Men seem to agree in. This is a Principle, which is thought to extend it self to the Dens of Thieves, and [54]the Confederacies of the greatest Villains; and they who have gone farthest towards the putting off of Humanity it self, keep Faith and Rules of Justice one with another. I grant that Outlaws themselves do this one amongst another: but ’tis without receiving these as the innate Laws of Nature. They practise them as Rules of convenience within their own Communities: But it is impossible to conceive, that he imbraces Justice as a practical Principle, who acts fairly with his Fellow High-way-men, and at the same time plunders, or kills the next honest Man he meets with. Justice and Truth are the common ties of Society; and therefore, even Outlaws and Robbers, who break with all the World besides, must keep Faith and Rules of Equity amongst themselves, or else they cannot hold together. But will any one say, That those that live by Fraud and Rapine, have innate Principles of Truth and Justice which they allow and assent to?

§ 3. Perhaps it will be urged, That the tacit assent of their Minds agrees to what their Practice contradicts. I answer, First, I have always thought the Actions of Men the best Interpreters of their thoughts. But since it is certain, that most Men’s Practice, and some Men’s open Professions, have either questioned or denied these Principles, it is impossible to establish an universal consent, […] without which, it is impossible to conclude them innate. Secondly, ’Tis very strange and unreasonable, to suppose innate practical Principles, that terminate only in Contemplation. Practical Principles derived from Nature, are there for Operation, and must produce Conformity of Action, [56]not barely speculative assent to their truth, or else they are in vain distinguish’d from speculative Maxims. Nature, I confess, has put into Man a desire of Happiness, and an aversion to Misery: These indeed are innate practical Principles, which (as practical Principles ought) do continue constantly to operate and influence all our Actions, without ceasing: These may be observ’d in all Persons and all Ages, steady and universal; but these are Inclinations of the Appetite to good, not Impressions of truth on the Understanding. […]

§ 4. Another Reason that makes me doubt of any innate practical Principles, is, That I think, there cannot any one moral Rule be propos’d, whereof a Man may not justly demand a Reason: which would be perfectly ridiculous and absurd, if they were innate, or so much as self-evident; which every innate Principle must needs be, and not need any Proof to ascertain its Truth, nor want any Reason to gain it Approbation. He would be thought void of common Sense, who asked on the one side, or on the other side went to give a Reason, Why it is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be. It carries its own Light and Evidence with it, and needs no other Proof: He that understands the Terms, assents to it for its own sake, or else nothing will ever be able to prevail with him to do it. But should that most unshaken Rule of Morality, and Foundation of all social Virtue, That one should do as he would be done unto, be propos’d to one, who never heard of it before, but yet is of capacity [58]to understand its meaning; Might he not without any absurdity ask a Reason why? And were not he that propos’d it, bound to make out the Truth and Reasonableness of it to him? […]

[…]

§ 10. He that will carefully peruse the History of Mankind, and look abroad into the several Tribes of Men, and with indifferency survey their Actions, will be able to satisfy himself, That there is scarce that Principle of Morality to be named, or Rule of Vertue to be thought on (those only excepted, that are absolutely necessary to hold Society together, which commonly too are neglected betwixt distinct Societies) which is not, somewhere or other, slighted and condemned by the general Fashion of whole societies of Men, governed by practical Opinions, and Rules of living, quite opposite to others.

§ 11. Here, perhaps, ’twill be objected, that it is no Argument, that the Rule is not known, because it is broken. I grant the Objection good, where Men, though they transgress, yet disown not the Law; where fear of Shame, Censure, or Punishment, carries the Mark of some awe it has upon them. But it is impossible to conceive, that a whole Nation of Men should all publickly reject and renounce, what every one of them, certainly and infallibly, knew to be a Law. […]

§ 12. […] Let us take any of these Rules, which being the most obvious deductions of Humane Reason, and conformable to the natural Inclination of the greatest part of Men, fewest [60]People have had the Impudence to deny, or Inconsideration to doubt of. If any can be thought to be naturally imprinted, none, I think, can have a fairer Pretence to be innate, than this; Parents preserve and cherish your Children. When therefore you say, That this is an innate Rule, What do you mean? Either, that it is an innate Principle; which upon all Occasions, excites and directs the Actions of all Men: Or else, that it is a Truth, which all Men have imprinted on their Minds, and which therefore they know, and assent to. But in neither of these Senses is it innate. First, That it is not a Principle, which influences all Men’s Actions, is, what I have proved by the Examples before cited: […] it was a familiar, and uncondemned Practice amongst the Greeks and Romans, to expose, without pity or remorse, their innocent Infants. Secondly, That it is an innate Truth, known to all Men, is also false. For, Parents preserve your Children, is so far from an innate Truth, that it is no Truth at all; it being a Command, and not a Proposition, and so not capable of Truth or Falshood. To make it capable of being assented to as true, it must be reduced to some such Proposition as this: It is the Duty of Parents to preserve their Children. But what Duty is, cannot be understood without a Law; nor a Law be known, or supposed without a Law-maker, or without Reward and Punishment: So that it is impossible, that this, or any other practical Principle should be innate; i. e. be imprinted on the Mind as a Duty, without supposing the Ideas of God, of Law, of Obligation, of Punishment, of a Life after this, [62]innate. […] But these Ideas […] are so far from being innate, that ’tis not every studious or thinking Man, much less every one that is born, in whom they are to be found clear and distinct. […]

§ 13. […] I would not be here mistaken, as if, because I deny an innate Law, I thought there were none but positive Laws. There is a great deal of difference between an innate Law, and a Law of Nature; between something imprinted on our Minds in their very original, and something that we being ignorant of may attain to the knowledge of, by the use and due application of our natural Faculties. And I think they equally forsake the Truth, who, running into contrary extreams, either affirm an innate Law, or deny that there is a Law, knowable by the light of Nature, i. e. without the help of positive Revelation.

§ 14. […] But in truth, were there any such innate Principles, there would be no need to teach them. Did Men find such innate Propositions stamped on their Minds, they would easily be able to distinguish them from other Truths, that they afterwards learned, and deduced from them; and there would be nothing more easy, than to know what, and how many they were. There could be no more doubt about their number, than there is about the number of our Fingers. […] But since no body, that I know, has ventured yet to give a Catalogue of them, they cannot blame those who doubt of these innate Principles; since even they who require Men to believe, that there are such innate Propositions, do not tell us what they are. […] Nay, a great part of Men are so far from finding any such innate Moral Principles in themselves, that by denying [64]freedom to Mankind; and thereby making Men no other than bare Machins, they take away not only innate, but all Moral Rules whatsoever, and leave not a possibility to believe any such, to those who cannot conceive, how any thing can be capable of a Law, that is not a free Agent: And upon that ground, they must necessarily reject all Principles of Vertue, who cannot put Morality and Mechanism together; which are not very easy to be reconciled, or made consistent.

[…]

§ 20. Nor will it be of much moment here, to offer that very ready, but not very material Answer, (viz.) That the innate Principles of Morality, may, by Education, and Custom, and the general Opinion of those, amongst whom we converse, be darkned, and at last quite worn out of the Minds of Men. Which assertion of theirs, if true, quite takes away the Argument of universal Consent, by which this Opinion of innate Principles is endeavoured to be proved; […] concerning innate Principles, I desire these Men to say, whether they can, or cannot, by Education and Custom, be blurr’d and blotted out: If they cannot, we must find them in all Mankind alike, and they must be clear in every body: And if they may suffer variation from adventitious Notions, we must then find them clearest and most perspicuous, nearest the Fountain, in Children and illiterate People, who have received least impression from foreign Opinions. Let them take which side they please, they will certainly find it inconsistent with visible matter of fact, and daily observation.

[66][…]

§ 22. […]Doctrines, that have been derived from no better original, than the Superstition of a Nurse, or the Authority of an old Woman; may, by length of time, and consent of Neighbours, grow up to the dignity of Principles in Religion or Morality. For such, who are careful (as they call it) to principle Children well, (and few there be who have not a set of those Principles for them, which they believe in) instil into the unwary, and, as yet unprejudiced Understanding, (for white Paper receives any Characters) those Doctrines they would have them retain and profess. These being taught them as soon as they have any apprehension; and still as they grow up, confirmed to them, either by the open Profession, or tacit Consent, of all they have to do with; or at least by those, of whose Wisdom, Knowledge, and Piety, they have an Opinion, who never suffer those Propositions to be otherwise mentioned, but as the Basis and Foundation, on which they build their Religion or Manners, come, by these means, to have the reputation of unquestionable, self-evident, and innate Truths.

[…]

§ 25. […] Custom, a greater power than Nature, seldom failing to make them worship for Divine, what she hath inured them to bow their Minds, and submit their Understandings to, it is no wonder, that grown Men, either perplexed in the necessary affairs of Life, or hot in the pursuit of Pleasures, should not[68]seriously sit down to examine their own Tenets; especially when one of their Principles is, That Principles ought not to be questioned. […]

[…]

§ 27. […] And, indeed, if it be the privilege of innate Principles, to be received upon their own Authority, without examination, I know not what may not be believed, or how any one’s Principles can be questioned. If they may, and ought to be examined, and tried, I desire to know how first and innate Principles can be tried; or at least it is reasonable to demand the marks and characters, whereby the genuine, innate Principles, may be distinguished from others; […] When this is done, I shall be ready to embrace such welcome, and useful, Propositions; and till then I may with modesty doubt, since I fear universal Consent, which is the only one produced, will scarce prove a sufficient mark to direct my Choice, and assure me of any innate Principles. From what has been said, I think it is past doubt, that there are no practical Principles wherein all Men agree; and therefore none innate.

CHAPTER IV

Other Considerations concerning innate Principles, both speculative and practical

§ 1. HAD those, who would perswade us, that there are innate Principles, not taken them together in gross; but considered, separately, the parts, out of which those Propositions are made, [70]they would not, perhaps, have been so forward to believe they were innate. Since, if the Ideas, which made up those Truths, were not, it was impossible, that the Propositions, made up of them, should be innate, or our Knowledge of them be born with us. For if the Ideas be not innate, there was a time, when the Mind was without those Principles; and then, they will not be innate, but be derived from some other Original. For, where the Ideas themselves are not, there can be no Knowledge, no Assent, no Mental or Verbal Propositions about them.

§ 2. If we will attentively consider newborn Children, we shall have little Reason, to think, that they bring many Ideas into the World with them. For, bating, perhaps, some faint Ideas, of Hunger, and Thirst, and Warmth, and some Pains, which they may have felt in the Womb, there is not the least appearance of any setled Ideas at all in them; especially of Ideas, answering the Terms, which make up those universal Propositions, that are esteemed innate Principles. One may perceive how, by degrees, afterwards, Ideas come into their Minds; and that they get no more, nor no other, than what Experience, and the Observation of things, that come in their way, furnish them with; which might be enough to satisfy us, that they are not Original Characters, stamped on the Mind.

§ 3. It is impossible for the same thing to be, and not to be, is certainly (if there be any such) an innate Principle. But can any one think, or will any one say, that Impossibility and Identity, are two innate Ideas? Are they such as all Mankind have, and [72]bring into the World with them? And are they those, that are the first in Children, and antecedent to all acquired ones? If they are innate, they must needs be so. Hath a child an Idea of Impossibility and Identity, before it has of White or Black; Sweet or Bitter? And is it from the Knowledge of this Principle, that it concludes, that Wormwood rubb’d on the Nipple, hath not the same Taste, that it used to receive from thence? Is it the actual Knowledge of impossibile est idem esse, et non esse, that makes a Child distinguish between its Mother and a Stranger; or, that makes it fond of the one, and fly the other? […] The Names Impossibility and Identity, stand for two Ideas, so far from being innate, or born with us, that I think it requires great Care and Attention, to form them right in our Understandings. […]

§ 4. If Identity (to instance that alone) be a native Impression; and consequently so clear and obvious to us, that we must needs know it even from our Cradles; I would gladly be resolved, by one of Seven, or Seventy Years old, Whether a Man, being a Creature, consisting of Soul and Body, be the same Man, when his Body is changed? Whether Euphorbus and Pythagoras, having had the same Soul, were the same Man, though they lived several Ages asunder? Nay, Whether the Cock too, which had the same Soul, were not the same with both of them? Whereby, perhaps, it will appear, that our Idea of sameness, is not so settled and clear, as to deserve to be thought innate in us. For if those innate Ideas, are not clear and distinct, so as to be universally known, and naturally agreed [74]on, they cannot be Subjects of universal, and undoubted Truths; but will be the unavoidable Occasion of perpetual Uncertainty. For, I suppose, every one’s Idea of Identity, will not be the same, that Pythagoras, and Thousands others of his Followers, have: And which then shall be true? Which innate? Or are there two different Ideas of Identity, both innate?

§ 5. Nor let any one think, that the Questions, I have here proposed, about the Identity of Man, are bare, empty Speculations; which if they were, would be enough to shew, That there was in the Understandings of Men no innate Idea of Identity. He, that shall, with a little Attention, reflect on the Resurrection, and consider, that Divine Justice shall bring to Judgment, at the last Day, the very same Persons, to be happy or miserable in the other, who did well or ill in this Life, will find it, perhaps, not easy to resolve with himself, what makes the same Man, or wherein Identity consists: And will not be forward to think he, and every one, even Children themselves, have naturally a clear Idea of it.

§ 6. Let us examine that Principle of Mathematicks, viz. That the whole is bigger than a part. This, I take it, is reckon’d amongst innate Principles. I am sure it has as good a Title, as any, to be thought so; which yet, no Body can think it to be, when he considers the Ideas it comprehends in it, Whole and Part, are perfectly Relative; but the Positive Ideas, to which they properly and immediately belong, are Extension and Number, of which alone, Whole and Part, are Relations. So that if Whole and Part are innate Ideas, Extension and Number must be so too, it being impossible to have an Idea of a [76]Relation, without having any at all of the thing to which it belongs, and in which it is founded. Now, Whether the Minds of Men have naturally imprinted on them the Ideas of Extension and Number, I leave to be considered by those, who are the Patrons of innate Principles.

§ 7. That God is to be worshipped, is, without doubt, as great a Truth as any that can enter into the mind of Man, and deserves the first place amongst all practical Principles. But yet, it can by no means be thought innate, unless the Ideas of God and Worship, are innate. That the Idea, the Term Worship stands for, is not in the Understanding of Children, and a Character stamped on the Mind in its first Original, I think, will be easily granted, by any one, that considers how few there be, amongst grown Men, who have a clear and distinct Notion of it. […]

§ 8. If any Idea can be imagin’d innate, the Idea of God may, of all others, for many Reasons be thought so; since it is hard to conceive, how there should be innate Moral Principles, without an innate Idea of a Deity