Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

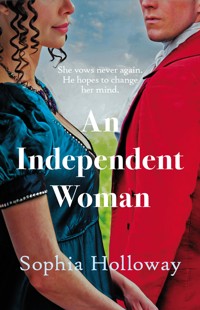

The newly widowed Lady Louisa Dembleby is immensely thankful to be released from an awful marriage and vows that she will never marry again. A quiet life of contented freedom with her cherished daughter lies ahead, but her resolution falters when she meets Major Benfield Barkby, recovering from serious wounds sustained fighting in Spain. Against the backdrop of the social season in Bath, gossip, grandmamas and a climatic duel look set to complicate any chance of a happy ever after. Readers love Sophia Holloway: 'A true classical Regency romance story, but with a fresh and new feel which brings it right up to date' 'This was really good, I enjoyed it a lot' 'I was definitely rooting for Ben and Louisa' 'It's fresh and engaging ... if you love Regencies with a little extra something, then this is a must, highly recommended from me!'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 508

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

AN INDEPENDENT WOMAN

SOPHIA HOLLOWAY4

5

For K M L B6

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Viscount Dembleby was interred in the family vault on a cold January afternoon, with all due obsequies, sober expressions and the usual lies about ‘what a loss’ and ‘fine fellow’ from people who either barely knew him, or did not much like him. He did have a few friends, but they could be counted upon the fingers of one hand, and none of them liked any of the others.

The ladies of the family did not, of course, attend the funeral, nor the reading of the will thereafter. It was a far from harmonious black-garbed quartet that sat in a small saloon, where the fire’s cheering red glow and crackle struggled to engender even a little physical warmth into a decidedly chilly atmosphere. The Dowager Lady Dembleby sat nearest to the fire, her visage stony. Her grief for her elder son was genuine, if not particularly deep, but added to it was a sense of raging resentment that he should have been so thoughtless as to have departed this life without an heir. He had thereby left the title and estates to his younger brother, who had been all but disowned when he had committed the unforgivable sin of marrying a young woman of whom his parent and brother disapproved. The 8Dowager actually felt hard done by. She loathed both her daughters-in-law, even though Dembleby’s wife had, briefly, been considered a reasonable match. It was a small consolation to his mother that he had lived to regret it.

The newly widowed Louisa, Lady Dembleby, did not look in deep grief. In fact, she did not look to be grieving at all. She sat, her hands folded in her lap, silent, looking out at a grey winter's landscape of empty parkland and sparse, denuded trees. She would not, she thought, miss the view, or indeed the house, which was old and rambling. The new Lady Dembleby was welcome to its rattling windowpanes, long passageways and the all-too-frequent presence of the previous châtelaine.

The newest Lady Dembleby, still unused to her title, was caught between a sense of awe at becoming the mistress of such an establishment, and terror at the knowledge that she would henceforth be the all-too-close neighbour of her dreaded mama-in-law, who would be bound to interfere. She was a quiet, mousey young woman, second of the many daughters of a Devonshire squire, whom the Honourable Robert Henley had met at a subscription ball in Exeter. Robert was himself quiet and rather bookish, and not much given to dancing. He even had aspirations of taking holy orders, though he had not voiced them to his brother or mother. The attraction had been mutual, and within three months her father had been shaking Mr Henley by the hand and wishing him well, delighted that he had got a younger daughter off his hands, and to the son of a viscount, even if he was not the heir. The only thing that the new Lady Dembleby now had in her favour, when 9it came to her mama-in-law, was her condition, which was very visibly ‘delicate’. If she did as her predecessor had failed to do, and provided a son and heir, much would be forgiven.

The final lady in the room was the only one who was not, in some shape or form, ‘Lady Dembleby’. Lady Felmersham was the widow’s mother, and technically there to support her daughter in her ‘time of desolation’. Since support did not seem to be needed, she felt very much in the way, and her own fear of the Dowager made her sit as far from the fire as possible, despite the cold seeping into her fingers.

The prolonged silence was broken by the opening of the door, and the entrance of Lords Felmersham and Dembleby, both looking suitably sombre.

‘Well?’ The Dowager, ignoring Lord Felmersham, addressed her remaining son.

‘It all passed off very … I mean … it was a good sermon,’ he managed, in a mild voice.

‘I have no interest in the sermon, Dembleby. The parson knows very well what is expected of him, and would not dare deviate from the tone that I instructed him to take. I take it there were no surprises in the will?’

‘Er, no, Mama. The Dower House is yours for your lifetime, of course, and’ – he cast a swift, apologetic glance at his wife – ‘you retain the family jewels.’ The Dowager smiled, almost graciously. ‘My brother made a small bequest to a friend, a memento, and of course Louisa has her third of the income, as long as she remains a widow.’ He looked at his sister-in-law, unsure whether to smile or 10not. He did not reveal the actual words of the will, which made it clear that his brother only left what the law decreed to his widow with extreme reluctance. ‘The rest passes to me and “my heirs lawfully begotten” as the phrasing goes.’

‘What of Emily?’ asked Louisa, frowning.

‘Um, well, no mention was made of her.’

‘What?’ Louisa got up with a rustle of black silk. ‘He made no provision for his daughter?’

‘No.’

‘Papa?’ She turned to her father.

‘I am sorry, my dear.’

‘So, he ignored her in life, and he does so also in death! Despicable!’ With which she flung from the room, followed by her mother, waving her nervous hands. Lord Felmersham would have looked apologetic, but for the grim smile upon the Dowager’s face.

‘If you will excuse me.’ He bowed, and left the room, following the sounds of his wife’s entreaties.

He found wife and daughter in a small, rather narrow room with dark panelling. It was really rather claustrophobic. Louisa was walking up and down its length, her hands clenched together in anger rather than some prayerful gesture, and his wife was perched upon the edge of an uncomfortable high-backed chair, making ineffectual soothing noises. His daughter looked at him as he shut the door behind him.

‘Papa, this is monstrous. It cannot be legal … his only child …’

‘I am sorry, my dear, but the lawyers say there is nothing 11that can be done. Dembleby himself expressed his surprise. Your late husband was of sound mind, and he made provision for you according to the rules. There was no legal requirement for him to do so for Emily.’ Lord Felmersham regarded his daughter with some sympathy.

‘Sound mind? How is it “sound mind” to leave not a penny to his only child as if … as if he cast a slur upon her, and me, even from the grave.’ Her frown deepened. ‘He blamed me for … when I lost the first. When Emily was born and he was told it was a girl he did not come to see her, or me. When he saw me next he told me he would “forgive me”, as though the gender of a child is in the remit of the mother. He attended her christening, for form’s sake only, and I doubt he saw her more than a dozen times thereafter. He wanted to forget she existed. No, I am wrong. He wanted to expunge the thought that she had come into being at all. Whenever he … he told me I was there to bear sons, and a wife who did not do that was no wife at all. So he cut Emily out of his will as well as his thoughts. How can I provide for her when she is grown? Oh!’ She paused suddenly. ‘It may even look as though … as if she is … as if I had … The shame of it! How dared he do this! How I despise and loathe the man.’ The widow’s two pale hands clenched in fists, and she continued to pace up and down.

‘Hush, Louisa. You must not speak ill of the dead.’ Her mother, edging so close to the edge of the chair she was in danger of slipping from it, spoke in a whisper.

‘Then I will never speak of him again, for I have not a good word to say of him.’

12‘You are overwrought.’

‘No, Mama, I am angry beyond belief.’ Louisa stood still at last, her cheeks flushed, and her grey-green eyes flashing. Her dark gold hair, which held hints of red in the sunlight, was accentuated by her blacks.

‘Er …’ Her father cleared his throat. ‘The Dowager has the Dower House for her lifetime. You will have income, of course, but there is no particular estate … no house. You will return home with us and …’

‘It will be like it was before you were married.’ Lady Felmersham smiled, hesitantly, and pleated her handkerchief. ‘Though not quite, with dear Amabel now married. And James may be home at the end of Trinity term, and …’

It could not be said that the widow regarded this with unalloyed pleasure. In fact, she regarded it without any pleasure whatsoever. It was, however, not a matter of choice. Going ‘home’ would mean being treated almost the same as when she was single, without power to order her own life. Whatever else marriage had given her, and it was not much, she had been mistress of a large house, someone who made decisions, organised things. Watching her mother dither her way through running Deerswell would be almost impossibly frustrating. She would become ‘poor Louisa’, little better than an unmarried daughter, excepting that she would not have to depend upon largesse in order to buy the smallest thing. Perhaps, when she was out of deep mourning, she might find some indigent female relative and set up a modest establishment in Bath. She would have to keep a close eye upon economy but at least 13she would be ‘free’, and what she saved would be invested to provide little Emily with something in the long-distant future.

She tried to be positive. In her period of deep mourning, her life would be restricted wherever she might reside, whether alone or with her parents, and at least she had Emily.

Whilst her brother-in-law and sister-in-law made vague offers for her to remain as long as she wished, the truth of the matter was that neither she nor they felt comfortable, and the Dowager was so keen that she depart she might almost have offered to pack her bags for her personally, although that might also have been to ensure that nothing that belonged to the Henleys was leaving the property. That ‘the child’ was going too meant nothing to her. Having brought two sons into the world, the Dowager took pride in the fact that she had never so blotted her copybook as to have been delivered of a daughter. She had even voiced this sentiment out loud.

Louisa therefore made preparations to leave with her parents two days after the funeral, accompanied by her maid, the nursemaid and the Honourable Emily Henley, who was most unlikely to see inside the house of her birth ever again. Since she was but two years old, she was blissfully unaware of all the upheaval.

Lady Felmersham had assumed the infant would travel in the second vehicle, with the maidservants, and was rather surprised to find her sitting beside her mama, and staring at her with big, blue eyes. Lady Felmersham hoped the child would not prove sickly upon the journey back to 14Berkshire, which would take some three hours. In fact, she curled up with her head upon her mama’s lap, and slept for almost the entirety, covered with a travelling rug.

Louisa knew that Emily would not remember this in later years, but she did not want her departure from the ancestral home of the Henleys to be one where she was among servants and dressing cases like a piece of luggage, though she was as relieved as her mama that Emily showed neither an inclination to fidget, nor to be unwell. She knew also that her mama felt that children, especially before they might be expected to converse in full sentences, should only be presented for a few minutes each day to their mama to be smiled upon, and of course for it to be seen that the nursemaid was doing her job properly. Lady Felmersham had had little contact with her children until they could be ‘interesting’, and certainly not in toddlerhood, when they were likely to behave erratically and want to touch things. For Louisa, however, her child was the focus of her life, the object of her love. The nursery, where her husband would never have thought to set foot, was an oasis of happiness in her life, and she had stolen happy hours there. Both her mama and mama-in-law had been horrified that she had fed the baby herself, and there had been a very vocal argument with her lord, who had forbidden her to do what was obviously ‘disgusting and common’. Louisa had carried on regardless. It had been something else chalked up upon the slate of ‘wilful and disobedient’, and, as time went on, ‘unworthy’.

The marriage had not been happy, although for her part, Louisa had entered it with high hopes, and under the 15impression that Lord Dembleby was, if not wildly in love with her, certainly very tenderly disposed. He had courted her with the expressions of devotion a young lady would consider evidence of affection, protestations that were proven empty once the knot was tied. Within a couple of months his interest in her was confined to whether or not she might be increasing, and efforts to ensure that this might be the case. He had been ‘very pleased with her’ when she had discovered that she was pregnant, and even more ‘displeased’ when she had lost the baby a couple of months afterwards. At a time when she had needed support, all she had received was blame, and she had realised that, to him, she was essentially an object, to satisfy his needs when he did not do so elsewhere, and most essentially to provide the next Lord Dembleby. It was hardly surprising that upon the birth of a reviled daughter, she had focused her life upon her.

When the carriage passed out of the gates of the estate, Louisa had given a deep sigh of relief. Returning to the home of her childhood was not going to be a backward step, but one towards her freedom. She must not see it as being trapped, for that was what she had been these last five years. She drifted into a reverie in which she had a nice little house all of her own, with no constraints upon where she must go, or who must or must not be invited to dinner. Widowhood was not like being a spinster, as far as Society was concerned. Society might not be very interested in her, but she would not have to have a chaperone at her shoulder, or ask permission to go out, or to buy a hat or even a horse. She would be patient.

16‘… and if you are very fortunate, Frederick Brailes might be persuaded … he always showed a marked fondness for you …’

Louisa blinked, and caught up with her mama’s conversation, which she had been hearing, but to which she had not been listening.

‘Such things are not for now, my dear,’ admonished Lord Felmersham, gently, seeing his daughter’s shock.

‘Nor for the future, Mama. Listen to yourself. You were all but barring the gates to Mr Brailes before I was brought out, not that I had any interest in him. Now you are saying I would be “very fortunate” if he were to renew his interest? Well, let us be clear upon one thing. I shall not enter the married state again, ever.’ This was said with an air of finality, and a great deal of defiance.

‘You are distraught, but …’

‘Distraught? Mama, I am jubilant.’

‘Really, Louisa, you simply cannot say such a thing.’ Her sire frowned.

‘Not in public, sir, perhaps, but it is how I feel. I have been liberated. Why, having experienced the barred cage, the … the suffocation of marriage, would I seek it again?’

‘A woman needs a man to guide her,’ averred Lady Felmersham.

‘This woman most certainly does not.’ Louisa snorted, and held her head high.

‘Oh dear me. I am not sure that my nerves will stand it.’ Lady Felmersham sniffed into her handkerchief. ‘Just promise me you will not reveal such sentiments to anyone else. Anyone. What would be said?’

17‘I care not.’

‘Then you are a fool, my girl.’ Lord Felmersham decided that if his daughter was going to be so frank, then it must be met with equal frankness. ‘Speak out in such intemperate terms and you will find yourself ostracised. You look forward to “freedom”, but being “free” will be meaningless if you are avoided by decent company for being outrageous. Think also of this …’ His tone softened, for he was very fond of his elder daughter. ‘Whatever unpleasantness existed in your marriage with Dembleby, the man is dead, and it ought to be buried with him. Making it known, publicising it in any way, will not only harm your reputation, but in the longer term will reflect upon Emily. She is too young to recall him. What are you going to say to her as she grows? Even if her father did ignore her, is it kind to tell her?’

‘No.’ Louisa closed her eyes and sighed. ‘But I shall not exchange my widowed state for the bonds of marriage, Papa. Of that you can be certain.’

CHAPTER TWO

Deerswell was a neat Palladian mansion of tidy proportions approached by a driveway that curved through a park that no longer held deer. In some ways she felt it was welcoming, for she had spent a happy enough childhood there, and, unlike the rambling, sixteenth-century Dembleby family seat, it was light, and had few draughts. It was, however, about to become her ‘prison’ during her months of enforced social seclusion, and she had no illusions that, thereafter, their neighbours would be eager with invitations. A widow, especially one with a small child and nothing in the way of inherited estates, was an embarrassment and an odd number. If invitations included her, then one could be sure that they would be grudging.

The horses slowed and came to a halt before the portico, and the steps were let down. Louisa woke her sleeping child, who made a mild grizzling noise indicative more of confusion than annoyance. She spoke soothingly, and although Betty the nursemaid was already standing ready to take the little girl, Louisa smiled and shook her head. She remembered this place from her earliest memories, 19which must have been when she was scarcely older than Emily. Perhaps in after years her child might have an image of this, a faint memory. The butler, Linslade, came out, his normally impassive face looking decidedly benign.

‘We have made all necessary preparations, my lord.’ He turned slightly towards Louisa. ‘The nursery has been thoroughly aired, your ladyship, and your own bedchamber prepared. If I might be so forward, although the circumstances are tragic, it is nice to have your ladyship home again.’

‘Thank you, Linslade.’

He bowed them into the large, marble-floored hall, from which ascended a broad staircase that bifurcated at a half landing, upon which the slightly battered bust of a tight-lipped Roman dignitary, a memento of her grandfather’s Grand Tour, stared from his rouge marble plinth. Louisa’s smile broadened. The figure was nameless, but her uncle Edward had christened him ‘Horace’ a generation ago, and so he had remained. He felt as welcoming as Linslade. She relaxed. Perhaps life would not be so bad after all.

‘I shall lie down for an hour,’ said Lady Felmersham, pulling off her gloves. ‘Travelling is so very tiring, and I simply could not eat a thing at present.’

‘Well, I am hungry and I daresay Louisa is also.’ Lord Felmersham looked at his daughter, who was now passing Emily into Betty’s care.

‘It felt too momentous to have breakfast, but I would most certainly find food welcome now.’

‘I will have a repast prepared immediately, my lord.’ Linslade bowed and went to arrange this, while the family 20went to change, and, in Lady Felmersham’s case, retire to her day bed.

Father and daughter therefore partook of chicken and fruit in companionable silence until such time as the servants withdrew.

‘You know, my dear, it is good to have you home, as Linslade said. If you make the necessary adjustments I am sure you can be … content here.’ He paused for a moment. ‘Your mama feels it very keenly, having you once more under our roof. Not because it is in any way a reflection upon you, or indeed us, but because she worries about your future.’

‘My future, Papa, may not be very exciting, but it is secure. Dembleby could not take that away from me. My only concern is for Emily, when she is grown.’

‘I will do what I can, you know that.’

‘You should not have to, Papa.’

‘I know that too, but there is no point in raging against what we cannot alter, nor in looking back in bitterness.’

‘No, sir, no point. Were it not for Emily I would elide the last five years from my memory, I assure you, in their entirety.’

‘Yes, but you have … matured. You have had the running of your own house. You cannot simply take up your previous life as if waking from a sleep. I am not unaware that it will be difficult for you, but I ask that you try and curb your frustrations with regard to your mama’s indecisiveness.’

‘I … shall try, Papa, truly I shall.’

‘And you have to realise that she will not cease to hope 21that you will remarry. I know that your experience of marriage has not been … good, but in general it does provide advantages. She is acutely aware of that.’

‘Yes, alas, she is. But she is destined to be disappointed. Now, let us not be so serious. Tell me what I ought to know about your … our … neighbours.’

It was strange, thought Louisa, during the first weeks back at Deerswell, how one could adapt to inactivity. Whilst her fresh widowhood imprisoned her, the weather conspired to ensure that she was not alone in her confinement. Heavy snow made venturing outdoors impossible, even as far as the church on one Sunday, and any socialising with neighbours was out of the question. Lord Felmersham sought solace in his library, Louisa in the nursery, and Lady Felmersham in changing the menus for the week upon a near daily basis. Thankfully, the cook was so used to her ladyship’s ‘mind flits’ he did not throw up his hands and threaten to pack his bags and trudge to a freezing death in the snowdrifts. He did not even mutter Gallic imprecations carefully culled from his mentor’s extensive vocabulary, for the cook hailed not from Paris but Peterborough. However, by Easter, which fell at the end of March, the snow had dwindled to sad, icy patches cowering in hidden corners, and spring was emerging in leaf, flower and birdsong. Lady Felmersham took out paper and pen, and celebrated by asking the squire and his wife to dinner, artlessly including their son and unmarried daughter, and old General Cowley, who had been a friend of Lord Felmersham’s for many years. As she said to 22Louisa, it was nothing that her blacks would preclude her attending, being small, private, and all people whom she had known since childhood. This was perfectly true, but the idea that her mama was actually inviting Sir Daniel’s son to dinner would have made Louisa laugh, had it not been so annoying. There was no great fault of character patent in Frederick Brailes except that he had, inexplicably to Louisa’s mind, developed a ‘passion’ for her when she had emerged from the schoolroom. This had resulted in some execrable verse, posies of flowers and a tendency to adopt a fawning manner whenever he encountered her. She had found it, at seventeen, mildly flattering and then very silly. He was three years her senior, but had lacked the assurance of manhood, being very much still upon its cusp. He also had a tendency to speak in a succession of disjointed phrases rather than sentences, as his thoughts tumbled from his lips without any noticeable structure or arrangement. He reminded her of a persistent, buzzing fly. Had he been such, Lady Felmersham would have swatted him. Back then, dreaming of a stunning marriage for her daughter, she had done everything in her power to keep him at a distance, short of instructing the gamekeepers to set traps at the gates.

Louisa had not seen him since her marriage. Dembleby had never visited his parents-in-law, and had entertained them but twice, reluctantly. She was not quite sure what to expect when the squire and his family were announced, for she was honest enough to admit that the callow youth of twenty might be approaching a man of sense by twenty-eight.

23In Frederick Brailes’ case, this was not so. Sir Daniel was a kindly man with slightly bulging eyes and ruddy cheeks who might, in other garb, have passed for a yeoman farmer. He looked the sort of man who laughed loudly at his own witticisms, but in fact he was quiet, courteous and one who listened rather than spoke. His wife made up for this, being a lady with the ability to take a conversation through a wide variety of topics without ever apparently needing to draw breath. Frederick, upon whom she lavished excessive maternal devotion, took after Lady Brailes in looks, as did their second daughter, now successfully married. Their other surviving daughter took very much more after her sire in colouring, to her mama’s distress, and no amount of applying lotions to her cheeks and restricting her diet could make her other than rosy cheeked and buxom. In an age when young ladies were attired to exhibit a slender form, her more hourglass figure did not show to advantage. Miss Caroline Brailes had, at only one and twenty, already resigned herself to being ‘the support to her parents in their later years’. Louisa felt some sympathy for her. She greeted them all with the ease of many years’ acquaintance, to which was added the assurance of the married woman.

General Cowley was over seventy, ramrod straight, with high cheekbones and an aquiline nose. His eyes held a twinkle, and his laugh was a sharp bark, which never failed to make Lady Felmersham jump. Louisa could remember him from when her papa had taught her to play chess, and had permitted her to stand beside his chair when he and the general had battled with pawn and bishop. He 24might be aged, but he was astute, and the woman before him was very clearly not one in the depths of grief.

‘You look in good health, ma’am,’ he said, ‘and I am delighted to see you again, despite the circumstances.’ He did not offer insincere and unwanted condolences.

‘Thank you, sir, but if you persist in calling me “ma’am” you will be in my black books. Why, you are almost family.’

‘Very kind of you … my dear.’ His voice dropped to merely a penetrating whisper. ‘One ought not to say it, but you look very fine in black.’

‘I think I will be glad to wear colours again, though, at the end of my mourning. It is rather depressing having no choice but black every morning.’

‘I rather enjoyed not having to worry about what to wear every day when in uniform.’

‘Yes, dear sir, but you are a man. We females find little things like selecting a gown far more interesting.’

‘Hmm, well, if you say so, but I doubt very much whether your mind revolves about such issues.’

‘Alas, I have little more to consider now. The running of a house was a position of command, you might say, and I miss that, as I am sure you understand.’ There was a touch of regret in her voice.

He nodded, and moved on to speak with Sir Daniel.

Lady Felmersham had pondered over the seating at dinner. With so few, and of such long-standing acquaintance, it felt acceptable to be informal. She eventually placed Louisa between General Cowley and Frederick Brailes. Conversing with both, Louisa found the contrast stark. 25The general was in good spirits, happy to make her smile, and to talk about his son, at present upon the staff of the recently knighted Sir Rowland Hill in the Peninsula. Upon her right-hand side, Frederick Brailes spoke in vaguely hushed tones that he felt suitable for her bereaved state, and when he heard the old gentleman chuckle, he actually winced.

‘I must apologise,’ he murmured, when Louisa turned to speak with him.

‘Apologise?’

‘For the general, Lady Dembleby. He fails to see that such … levity and … how could you be interested in a war?’ He shook his head. Louisa bit back a swift retort.

‘I hardly think any apology is needed, sir, and even if that were the case, you are not the one to make it.’ She spoke evenly, containing her annoyance, but he took it another way.

‘No, I suppose I cannot be held responsible for … but as a gentleman, ma’am, I can only …’

‘… curb his tongue,’ the general barked, ‘and I said to him …’ It was some story he was recounting to Miss Brailes, but Louisa had the distinct impression he had overheard the comments.

Frederick Brailes either could not or would not believe that, but he paused for a moment.

‘Your situation, ma’am, left as you are … with an infant …’ He made it sound a burden too heavy to bear. ‘The responsibility … and none to guide you …’

Louisa wondered if he had ever finished a sentence, and her hand gripped her fork rather tightly.

26‘Of course none of it could have been foreseen, and your poor husband … if I may mention him without distressing you …’

‘I would rather that you did not mention him,’ managed Louisa, controlling herself.

‘Oh yes … my profuse apologies … thoughtless of me … Your desolation … So tragic.’

‘What exactly are you attempting to say, sir?’ Her voice was crisp, not, as he had expected, upon the verge of tears.

‘Why … er, that no man would wish to leave a young wife alone, as you are.’

‘I am not alone, Mr Brailes, please observe. I am surrounded by my family.’

‘But it is not the same as having that guiding hand of a husband, one man upon whom you might rely in all matters.’

‘You think a woman incapable of making decisions?’

‘No, no, not within her sphere, but the important ones—’

‘I once knew an officer of engineers,’ said the general, suddenly turning to Louisa with slightly narrowed eyes, ‘and he dug this enormous hole into which he placed a mine, lit the fuse and then fell over within five yards of it. That is the trouble with digging holes.’

Louisa was looking directly at him, and their eyes met and held. Her lips twitched, and she bit them to prevent herself from grinning at him.

‘I am thinking of having a whole border dug over and filled with white roses,’ declared Lady Felmersham, trying to steer the conversation.

27‘But my dear Lady Felmersham, do they not spoil terribly in the rain? I am convinced that they do so more than the red ones,’ Lady Brailes picked up the thread, ‘and I simply cannot get roses to last well in water, no matter what I do. They are meant to be romantic, I know, but they are not at all practical. It is perhaps the combination of colour and perfume that makes the rose so popular, and can you imagine our history having “the Wars of the Carnations”? It would sound perfectly silly, not but that fighting people in your own country, one’s own countrymen, not invaders of course, is both sad and really very shortsighted. I never liked that Cromwell man. I saw a picture of his portrait in a book once, and he made me positively shudder. Not, of course, that I am bookish, but my governess was determined that we, my sisters and I, ought to have a grasp of English history, for what is history but the present when it is a bit older.’ She scarcely drew breath between sentences, and General Cowley gazed at her in stupefaction, his wine glass raised halfway to his lips, for a full half minute.

‘Might I interest you in some of the raised pie, General,’ suggested Louisa, breaking the spell.

‘Wha— Oh, yes, yes, thank you, my dear.’

The ladies withdrew, leaving the gentlemen to their port. The two older women sat upon a sofa to enjoy local gossip, leaving Louisa and Caroline Brailes together.

‘I do so like General Cowley,’ said Miss Brailes. ‘He does not actually treat one as if lacking any sense.’

‘Very true.’

28‘Unlike my brother. The awful thing is that he is completely sincere. I ought not to say it, but there.’ She sighed.

Louisa had not known her very well, other than as Harriet Brailes’ little sister, there being four years between them at a stage when that was quite important. At fourteen, Caroline had still been very much in the schoolroom, when Louisa was making her curtsey to Society, and she had only been about to leave it when Louisa married. It came as something of a shock that she was as unlike her siblings in character as she was in looks.

‘He, um, means well,’ offered Louisa, weakly.

‘And could anything be more damning, ma’am?’ Caroline still looked embarrassed.

‘Oh, please, do not stand upon formality with me, for it makes me feel positively ancient, and I fear in the next months nearly all those whom I meet will be at least twice my own age. Your sister and I were upon quite close terms, even if we have but corresponded little since our lives diverged.’ She laid a hand upon Caroline’s arm, and the deep pink cheeks reddened even more.

‘Thank you. It is perhaps not so strange, but once others have also decided that one is never going to marry, there is a distancing, as though spinsterhood were infectious.’ Caroline gave a twisted smile.

‘Well, in my case, widowhood is remarkably similar. Had I “behaved correctly” and produced a son, I would still run my own home, or rather, his, and be treated as an adult. As it is … I feel closer to being a spinster than married.’

‘“Behaved correctly”? Goodness me, what a way to put it.’

29‘That was the view of my mama-in-law, and also my husband.’ Louisa kept her voice even.

‘I do not know what to say.’

‘There is nothing. Now, let us not think of such things, and instead let me, without even asking my mama’s permission, invite you to come to take tea with me. Would next week be suitable?’ Louisa smiled conspiratorially.

The gentlemen did not linger over the port, for which Mr Brailes was probably very grateful, since the other three were all of at least a generation older than himself. Added to which, the general was inclined to give him looks that had caused many a junior officer to quake in his boots in the distant past, even if the eyes were now a little rheumy. It had been his intention to position himself for conversation with ‘poor Lady Dembleby’, but the old gentleman was remarkably spry, and beat him to it.

‘There,’ murmured the general, with a grin at Louisa, ‘cut him off. Saved you from any more of his da— shed foolishness. What are men come to these days? I may be old, but I am still able to outflank the enemy.’ He twinkled, and gave a bark of laughter, which made Lady Felmersham give a start.

‘You are indeed, for which many thanks, although we should not be saying any of this, dear sir.’

‘Rubbish. Cannot bear to see a woman treated as though she were incapable of anything beyond … flower arranging. My own dear late wife followed the drum when we were in the Americas, and was more competent and decisive than half the staff officers. Now, tell me, have you kept up with your chess playing?’

30‘Alas no. My husband did not play, although I have been soundly beaten by my papa upon several evenings since my return to Deerswell. I fear I am no fit opponent.’

‘Well, I am not as nimble brained as once I was. Cannot see as many moves ahead as I would wish. If you are permitted to visit a lonely old fellow without a chaperone, then do come over to Stamhill some afternoon and perhaps we can play chess as badly as each other.’

‘That, General, would be a real pleasure. If I send a note to see if you are in …’

‘In? Why should I go out, beyond my morning constitutional now the weather is better? I will be in, never you fear, and I rarely have visitors, and most certainly not beauteous ones.’

‘You put me to the blush, sir.’

‘Ha! What would be impertinence in the young is tolerated in the very old, and anyway, I am being perfectly honest, not flattering. Men flatter to get what they want, and I am too old to want more than an hour of good company and a game of chess. Look at me straight. When a man gives you truth, my girl, you will see it in him, not hear it. Words are just … words. There, that is the advice of this old soldier, and far too solemn for the evening. The fool is hovering, and all words. Do you want me to retire from the field and let him gabble at you?’

‘I think the tea tray is being brought in, so the party will break up shortly. I ought, I know, to let Mr Brailes have his speech with me. This way it will not be for long. Thank you, General. I know I can rely upon you for strategy.’

‘Tactics, my dear. Strategy is the planning of a campaign, 31tactics for the battle and skirmish.’ He rose from the sofa, very slightly unsteady. She stood also.

‘I stand corrected.’ She smiled, so broadly it might almost have been described as an unladylike grin, took the old man’s hand and squeezed it, curtseying as she did so. He bowed, not deeply, but that was the constriction of an aged back, and stepped away. Mr Brailes, seizing his chance, very nearly thrust himself in front of her, and saw the smile fade to cool hauteur.

‘At last, ma’am … I feel you do not comprehend how … I am so very aware of your unfortunate position … how difficult it must be …’

Louisa’s responses became automatic and anodyne, and she longed for her bed.

CHAPTER THREE

Lady Felmersham felt that the evening had gone rather well, though she gently admonished her daughter for spending so much time with ‘old General Cowley’ rather than ‘young Mr Brailes’.

‘He is a dear man, of course, but you must think of the future, Louisa.’

‘I was. He has invited me to go and play chess with him. Is that not nice?’ Louisa smiled.

‘I do not mean the immediate future. You will not be in your blacks forever. I am not suggesting that you do anything so unladylike as set your cap at him, but …’

‘Oh no, I would never do so. He is old enough to be my grandfather.’ Louisa kept a straight face.

‘What? No, no, not the general, Mr Brailes.’

‘Mama, please. You do not listen to me. I have no wish to remarry, and least of all would I consider Frederick Brailes.’

‘He is not perfect, I grant you, and we would never have considered him for you back then … but he may be all you can get, Louisa.’

Louisa gave up. Her mama did not.

33Miss Caroline Brailes, far more welcome than her brother, came to take tea the following Wednesday. Lady Felmersham, with rare tact, withdrew after a single cup of tea, and a very small cake, to give ‘the girls’ the chance to chatter, although neither were the sort to only discuss fripperies and the latest edition of La Belle Assemblée. Having had to be reminded just once that it should be ‘Louisa’ and ‘Caroline’ between them, the squire’s daughter stirred a small lump of sugar in her tea, very thoughtfully, and broached the subject uppermost in her mind.

‘When we spoke the other evening, you seemed to think widowhood and spinsterhood much the same thing, but surely that is not the case. You are not pitied, the way the unmarried daughter is pitied.’

‘No, I am not, but what I see is merely a different form of pity.’ Louisa grimaced.

‘You at least found a husband. That is “success”, and the reverse is “failure”, in the eyes of the world.’

‘I will admit that to be true, but if marriage is a victory I found it to be a very hollow one.’ She sounded bitter.

‘But there are marriages where there is contentment, even … passion.’ Caroline frowned.

‘Yes.’ The admission was grudging.

‘So at least there is a chance of happiness if one marries.’

‘Yes, that must be so.’

‘And I cannot see that there is such a chance if one is without means, and dependent upon one’s family. I will be there to care for my parents when they grow old, but I will always be something of a child to them, not a real adult. Thereafter, my future will lie in the hands of my brother, 34and presumably his wife. I will be surplus.’ Caroline paused and took a deep breath. ‘It is not a pleasant thought.’

‘Tell me, do you think I make too much of my own trammelled state, Caroline?’

‘I would not be so presumptuous, but, forgive me, although you speak from experience, I cannot believe it to be a universal one.’

‘I will admit my position, since I will have some form of monetary independence, is not as bad as the one you paint of your future, but the price was high, too high.’

‘But when you married, did you have no idea …?’

‘I entered the married state as full of hope as any bride, no doubt, and if not subject to the pangs of love, then anticipating affection. I blinded myself to the truth in the hope of a fantasy.’ Louisa sighed. ‘Perhaps that is why I am so bitter, and bitter I am. I feel I was cheated, duped. Do you know, dear General Cowley said something to me after the dinner that I so wish I had been told years ago. He said that when a man speaks truth to me, I will see it in him, not hear it in the words.’

‘Goodness, that sounds very deep and philosophical.’ Caroline blinked.

‘But I think he was very right, and he, I promise you, is a man who speaks true.’ Louisa smiled. ‘If he were but twenty years the younger and I twenty older, I think I really would set my cap at him.’ She giggled. ‘Shameful, am I not?’

‘He is such a dear, though he would hate to be thought that. He does not treat one as …’

‘Vapid? I put it in part down to his late wife, who must have been a very resourceful lady, from what he has said 35of her. I think if ever he believed ladies weak, then she disabused him of the idea.’ She sighed. ‘If only more men were like him.’

‘Perhaps we ought to put an advertisement in the newspaper, “Wanted: Sensible, single military man who does not think ladies are weak and useless, interested in having a wife.”’ Caroline grinned. ‘You see, I am as bad as you. It does sound very prosaic, and not at all romantic.’

‘Romance is an illusion. Prosaic would do far better, I am sure. Now, do take another biscuit. It is so much easier than choosing men.’ They both laughed.

Louisa was rather surprised, and certainly pleased, to have found two friends to visit, and when she went to see Caroline, the improving weather gave the two young ladies the chance of delightful walks, thus escaping from both her fussing mama and irritating brother.

Visits to the general were confined to within doors, of course, but she never found them boring. Their chess game was of a sufficiently similar standard that one person was not always going to win, and if the general was sometimes distracted from the pieces on the board, his stories were always interesting, frequently humorous, and only very rarely not fully expurgated for a lady’s ear. However, by the time the old gentleman realised he was deep in a tale that was a little too colourful for his guest, he had usually gone so far that Louisa told him she would only guess something far ‘worse’, and then promised not to reveal their conversation.

For his part, she was a breath of fresh air in his somewhat 36lonely life, and the presence of a young and beautiful woman who left a scent of roses in his study was something for which he would have got down on his knees and given thanks, had he had any chance of then getting up again without assistance.

Spring glided into summer, as the leaves lost their newly unfurled brightness, and the swallows and house martins returned to the eaves. Louisa could not claim she was discontented, but her mama did not run the house as she had run hers, and things that she had not noticed as an unmarried girl of nineteen jarred upon the widow of twenty-five. At times she had to walk away, and when she did so it was nearly always to the nursery, where little Emily was perfectly content and adding to her vocabulary by the day. It was enough, or rather she kept telling herself it ought to be enough.

She had a few correspondents, ladies she had known during her presentation Season who were now married, and her old governess, but she did not receive many letters. It was therefore a surprise to receive one in a very neat hand from a firm of Bath solicitors. Upon opening it she sat down hurriedly, read it three times, and went in search of her father.

‘Good grief! Well, there is no doubting the truth of it. I believe your mama was always hopeful that your godmama would leave you some piece of jewellery or other, but this … this is far more than anyone would expect. You will be able to put plenty by in funds and secure your future very nicely from the sale.’

37‘Sale? Papa, if she has left me a house, an estate, might I not live in it?’

‘But you live here, Louisa.’

‘I am living here, yes, Papa, but this would be a place of my own, a house to run again.’

‘I do not think your mama will approve.’

‘I doubt it very much, but, Papa, I do not wish to be forever powerless, never taking decisions for myself, and in the years to come what would a widowed sister be to James other than a nuisance, if he were married?’

‘You could buy somewhere if that happened, with the money.’

‘But it is within little more than an hour’s journey from Bath, and a house intended for me.’

‘I am sure old Lady Frampton did not mean it quite that specifically, my dear child.’

‘But I would like to consider it, Papa. I really would.’

‘We shall see what your mama says.’

‘Unthinkable.’ That was Lady Felmersham’s reaction. ‘You cannot imagine how isolated you would be, and you are too young to be on your own, even as a widow.’

‘Then I will engage a companion of suitable years. I cannot see that I would be more isolated than I am here.’

‘We are not keeping you cooped up, Louisa.’ Lord Felmersham frowned.

‘No, Papa, but the majority of people I know and meet here are those I have known all my life. Most of the young women have got married and moved further away. I would find myself among new people, and, although I had not 38mentioned it, I had already thought that perhaps I might rent a house in Bath next year and …’

‘People will say we cast you out,’ bemoaned Lady Felmersham, and wrung her hands, ‘and Heaven knows what you may do without someone to guide you.’

‘Why should they say so, if I have inherited an estate?’ Louisa ignored the idea that she was incapable. ‘It is hardly setting myself up in some out-of-the-way cottage. I do not recall an awful lot about the house but …’

‘It is probably falling down by now. It is quite old.’

‘Mama, Dembleby’s house went back to the Tudors. Queen Anne seems almost modern to me.’

‘Can you mend a roof?’

‘Er, no, Mama, but then nor could Papa. We would find a man to do so, he and I both.’

‘Yes, but he would not be duped. They would all think to hoodwink you, being a mere woman.’

‘If they thought that they would be in for a nasty surprise,’ declared Louisa, with some heat.

‘I cannot think why you would want to live on your own in the middle of nowhere.’ Lady Felmersham was nothing if not persistent.

‘Elliston Court is but a mile or so from the town of Frome, Mama, not in the middle of a moor, or up a mountain.’

Despite this, Lady Felmersham was most distressed, and her lord took his daughter aside and requested that she think hard about the decision.

‘I do not say more, Louisa, but I do not want you to do something you will regret.’

39‘Papa, if the worst happened, and I found I disliked it, would you bar the door to me if I returned like some prodigal?’

‘Of course not.’

‘Then I risk a little expense, and my pride. However, I agree it is not a thing to be decided upon the spur of the moment. I will think on it, I promise.’

She did think about it, and it gave her several disturbed nights, but she knew that her thoughts all swayed her one way, which concerned her. Aware of her own bias, and that of her parents, she sought more impartial advice.

The next day she went to see General Cowley, knowing he would give her honest answers, and sensible ones too. By default, he invited her to set up the chess board between them, and rang for a glass of ratafia for his guest. It was not a drink that Louisa liked very much, but he considered it the drink to serve a lady, and she never liked to refuse.

Louisa set out her pieces in near silence, and the general watched her, and, as she set the final pawn in place, put out his hand and laid down his king, as he would if he conceded.

‘Sir?’

‘You will not play a game worthy of you if burdened. You will find me a good listener, as long as you speak clearly. My hearing is not as good as it once was.’

‘Am I that obvious, General?’

‘To me, my dear, yes.’

‘I … My godmama has died, and has, very much to my surprise, left her house, and its very tidy estate, to me. My 40parents assume I will sell the estate, and continue to live with them at Deerswell, but I am very tempted to live there myself. You see, although I love my parents dearly, I have been mistress of a house, I have made my own decisions and … it is not easy giving up “command”, sir, as I told you when I first returned here. You understand.’

‘Yes, I do, of course I do.’ He paused, leant back in his chair and folded his slightly gnarled hands before him. ‘It is an important decision, and you must make it as you would a chess move, thinking ahead. You wish to be your own woman, not still “daughter of the house”, but what is your aim, in the long term? Think strategy, not tactics.’

‘I want to live my own life, with my daughter, beholden to none, reliant upon no man.’ She looked at him squarely. ‘I have been married, been a man’s “possession”, and I do not want to be so again. Mama is convinced that women have to have a man to guide them in all things. My opinion of men is not so great that I think their guidance worth the having.’

‘Yet you have come to me.’ The general gave a wry smile.

‘Yes, I have, but … I trust but two men, sir, and the other is my papa, but in this he is too close, too involved to look at it clearly. I trust you, and I ask your advice.’

‘Will it cause a break between you and your parents?’

‘No. I think they will be initially disappointed, and worried also, but if I show that I can do this, they will not be cold towards me.’

‘Then have you any knowledge of the property that you have inherited? If it is in such poor repair that it would 41take much of the income just to restore it, then you should think twice.’

‘I went there once, and stayed with my godmama and visited Bath, for it is but a little more than an hour’s ride from there. The house is a good size, from the time of Queen Anne I believe, with well-proportioned rooms, as I recall. My godmama had lived in it for over thirty years, since she was widowed, and was an elderly lady.’

‘Which means I doubt much has been done in its upkeep. I speak as one who does not notice such things either. When my son Edward was home after the débâcle at Corunna he took me to task, respectfully of course, for the state of the roof and gutterings. I suggest, before you make your decision, that you send a man upon a reconnaissance, a man who knows buildings, and get his opinion. You do not want to go to a house falling about your ears.’

‘That is very true. But I have no knowledge …’

‘Your father’s man of business is the person to set about finding the man to do it, and it will also show that you are not letting heart rule head. If he comes back with a negative report, then sell, and if the money is sufficient, you might buy a property where you choose.’

‘You do not think me mad, dear sir?’

‘Not at all. I do think it likely that I am going to miss my games of chess, so shall we now play, while you are still here?’

Mr Herne, Lord Felmersham’s man of business, was, thought Louisa, just as one would imagine a man with that occupation. He was rather spare of frame, with a sharp 42nose upon which were perched a pair of spectacles that looked in imminent danger of falling off, and he had a slight stoop. His juniors found him daunting, but Louisa had known him for many years, and he had even, since her mama was not really up to the task, given her a few ‘lessons’ on the finer points of overseeing the quarterly accounts when she was about to become the châtelaine of a large house. Having been given the task of finding someone to survey the Somerset property, he had set about it with his normal thoroughness, and returned within ten days. His report was given in an even and noncommittal tone.

‘Mr Newton, of Bath, made a thorough appraisal of the property, my lady, and I consider him very trustworthy. He was engaged when the Dowager Lady Felmersham wanted to take a house in Bath many years ago, and his reports were very sensible. He says that the roof looks essentially sound except in one place towards the rear of the house, probably the effect of a winter gale not noticed and then allowing later gales to lift more tiles, and one chimney stack needs repointing. That means replacing the mortar between the bricks, my lady. There is damp in the roof space beneath the hole, but not such that it would not dry out if the repairs were made in the very near future. He also recommends that the gutters be cleared at the same time. The house has no major cracks, those that are present being merely the settling of a house that is over a century old. Interior decoration is, in his words, “tired”. The late Lady Frampton suffered from impaired vision in her last years, and in any case was not inclined, I am sure, to have the 43upheaval of redecoration. The stables and dairy are in good repair. Overall, he thinks that with a modest expenditure, the house could be very comfortable.

‘In addition, I requested that the list of servants currently employed be sent to me, and have also ascertained how many there were when the household was, shall we say, fully functioning. The butler is very elderly, and under the terms of her ladyship’s will, has a cottage upon the estate and a pension for his remaining years. There is still a housekeeper, a cook, a scullery maid and two housemaids, a coachman, groom and stableboy, three gardeners and a lad. I think besides engaging a butler, my lady, a footman would be wise. It is not a large residence, but there are times when a man’s stature and abilities are of use in a house, as well as being useful if you should be wishing to shop in Bath, for example.’

‘Mr Herne, do you think I am being reckless?’

‘It is not my place to say, my lady.’

‘But?’

‘But in purely practical terms, what you intend is not at all reckless. If the estate were sold, you could buy somewhere else, but I think it would not sell at as high a price as it would if given some renovation. If you had an inclination to reside in the vicinity of Bath, then it is a good situation. I have studied the accounts of the estate, the Home Farm and those lands leased out, and it could do with a little more oversight, but is not likely to make you a loss.’

‘Thank you, Mr Herne. I shall discuss this with his lordship and send you my final decision in the next few days.’

44‘As you wish, my lady. Do not feel the need to take such a step in haste.’

‘My own mind is very nearly certain. I simply wish to feel that I am … supported.’

‘Of course, my lady. I shall await your further instructions.’