Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

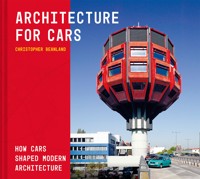

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

A smooth ride through the golden age of car travel, looking at both its cultural and architectural impact on the world. The culture of road travel and the road trip is arguably best reflected in the stationary spots found along the way. Christopher Beanland journeys through these built environments the world over, whose sole purpose is to cater to cars and those who drive them, and examines what makes them so alluring. Illustrated with 65 stunning photographs, Architecture For Cars explores everything from the brutalist fashions of listed UK petrol stations to the quirky and colourful drive-thrus found across the US. If you're interested in the autobahn churches of Germany, why Ed Ruscha felt drawn to painting gas stations, or you just enjoy the aesthetics of car-centric architecture across the globe, this book is for you. Also included are essays on wider topics such as roadside signs, drive-in malls and retail parks, cars on film, and roads that never were. This latest architectural deep-dive from Christopher Beanland focuses mainly on the 20th century, with an additional optimistic look towards the future: hopefully an electric vehicle-led existence will herald a new, greener 'golden age' for cars.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Flyover in Hong Kong, China

CONTENTS

Introduction

UK

EUROPE

AMERICAS

WORLDWIDE

ESSAYS

Super-sized Sculptures by the Roadside

Ring Road Poets of Coventry

Road Racing in Birmingham

The Car Park is Being Reinvented

The DeLorean Story

INTERVIEWS

Lisa Brown

Felix Torkar

Mary Keating

Chris Marshall

Dr Dawn Pereira

Sam Burnett

Rolando Pujol

Stuart Baird

Further Reading & Watching

Acknowledgements & Thanks

Index

INTRODUCTION

It’s the rhythm of the road that gets me. The syncopation of tyres travelling over tarmac with the thrum of an engine, the beat of music in the background, mixed with all the other vehicles, with chatter, with gusting winds. If all of history up to this point was largely about staying in place, the modern age was truly about speed and movement, about distance and the psychological feel of traversing that flattened landscape.

In my previous book, Station, I wrote about how railways had sped up the world, stretched the possible, linked people and places, altered our worlds and the worlds in our heads. Cars would change the game again because we weren’t the passenger – we were the driver.

The turning wheels revolve endlessly and go nowhere as the vehicle moves forward with us in it. The orbit echoes that of the planet the fiendish machine is going to destroy. The wheel we grip is circular. Everything moves forwards but it also doesn’t. It tricks us into thinking that. We’re not going forwards at all – we’re glued by gravity to this planet, we’re revolving on an axis and we’re spinning round the sun, and our lives go in a big circle from a helpless birth to a helpless death. We cast out in the middle like a swingball to enjoy the best of our lives when we are in control of them before returning to the bat, to the family and the drudgery and the predictable path.

East Cross Route / A12, London, UK

Flyover in Peshawar, Pakistan

But what a life we can make it in the middle. And the chance to now be able to explore Earth’s great limits is a wish from the genie. We rubbed the lamp. To pull in for a breakfast burrito in sight of Monument Valley, to traverse the pock-marked ash of Hawaii’s Big Island, to cross a whole continent (and stop for golf on the Nullarbor), to be able to creep close to Volcan de Agua and see it spitting fire across a Guatemalan sky – kids dream of adventure and now we have that chance. Nothing is stopping us from grabbing those opportunities.

Driving gives us the illusion of power and freedom. All these things are possible. They seem possible. All avenues are open. Car advertising sells us this dream. But driving atomizes us. It remakes us into grumpy, speed-obsessed individuals competing with others – the perfect capitalist citizens in other words.

I’m telling you right now, as I’ve done before, to quit your pointless jobs and make every second count as if it’s your last. But all you do is use the car as a runabout. Most cars trundle to Tesco and back, take the kids to the in-laws up the motorway and ferry one of the family to a job that will probably have been automated in the time between me writing these words and this book hitting the shelves. You don’t even really know if it’s me, Christopher Beanland, writing right now or an AI? Even more reason to take a punt on what really matters – but make sure it’s done compassionately and offset your carbon, thanks.

Ballard said the defining image of the 20th century was the person in the car. Those times have passed now. Although cars can give us adventure we must be mindful too – get on your bike, walk – why the hell do you have a car in the city? But for some great adventures, well, the car and the motel and the drive-thru are the guilty pleasures of the age. As with smoking and drinking and eating meat, driving will seem so passé to the youngsters of the next century, if we make it that far. Cars will rebrand and run on turnips. But we’ll still need to move. Yes, we must protect the Earth, and yes, we have to change; we have to basically stop all consumption. But we still need to move, to explore, to meet, to see, to hear, to taste, to love, to learn – these things are too important to say we’re just going to sit at home forever.

The open road was sold as a dream. Maybe you think I’ve been suckered. It’s worth pointing out not a penny from car or oil companies has been syphoned into my bank account to write this book – though one previous potential publisher suggested we should get it sponsored by one of them. Hmm. When those oil and car companies see what I’m about to say about them, they’ll be glad they didn’t put up any cash. Yet, I’m as taken in as anyone by the dream – particularly by the American dream – of an individual and abundant world driven by technology. And one where the National Parks were reachable and you could fuel up on burgers on the way there. Yes, it stinks. But to a younger me it was catnip. Maybe it still is.

ROADS

As Jonathan Meades pointed out, the Fens of England have a kindred spirit – not just in the Netherlands as you’d expect but in the American country-and-western belt. It’s ironic that growing up here the thing I wanted the most was America – its music, its films, its sneakers; I wanted to be there. Yet the thing I hated the most was long drives, and these are at the heart of any American adventure. Maybe it was the ‘being driven’. And it wasn’t the long drives so much as the shit roads. The A17 drove me bananas; how I envied those who lived off the A1 and could get everywhere so quickly.

I mention all this not out of narcissism or laziness but because the experience of driving and roads is a very personal one. We could say the experience of life itself is too, now that society is so grossly atomized and capitalism has delivered individuality par excellence. I could talk about the great movements and the history of roads and the structures near them (and I will) but it’s a peculiarly personal thing too. You will already be thinking, I’m sure, about your own childhood, about the routes you took to see family and to go on holiday, to go on day trips or to the supermarket. The things you saw, the places you stopped, the food you ate.

THE BEGINNINGS

The revolution began quaintly with The Wind in The Willows and with Lord De La Warr racing cars along Bexhill seafront on what would later become the site of one of England’s greatest buildings, the streamline moderne De La Warr Pavillion, and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang eccentricity. These were playthings for the rich but the democratization of the means would in time cause enormous changes.

London’s green cab shelters come from the age when horses pulled vehicles – we still talk about how much horsepower cars have. Slowly, life adapted with the first one-way systems and houses with garages in Birmingham. Road houses – pubs on a huge scale but with heightened ambitions – landed by arterial roads in Stirchley and Northfield in Birmingham too.

Cars and lorries needed fuel. Arne Jacobsen’s petrol station and the British modernist petrol stations were where you filled up. Even more outré gas-station designs emerged in the Eastern bloc, where Ladas needed to move somehow. Oil was going to be the must-have commodity – BP took a keen interest in Persia. Standard Oil was becoming an imperial-like player. Geopolitics shifted dramatically. Nodding donkeys became American icons. Wars were for black gold. Are they still? Unfortunately, yes.

FREEWAYS OF LIVING

The Futurama exhibition at the 1939 New York World’s Fair is a key moment in the story. The expo was a kind of internet of its day – where you could indulge in visions and ideas brought to life in a more immediate way than by just leafing through a book. Here Norman Bel Geddes’ ambitious model of a 1960s future America was brought to lavish life, and visitors rode round seeing with their own eyes what awaited them. It was completely prescient. Other pavilions at expos by General Motors, Ford and Shell promoted similar visions.

But could we not have had this and also kept the railway lines that connected and transformed 19th-century America (and so many other countries)? Imagine a world with the transport best of both.

TVAM building / former garage, Camden, UK

Germany built its first autobahns during a disgraceful period of forced labour and concentration camps. The Four Level Interchange in LA opened and the first parkways threaded up the Arroyo Seco Valley to Pasadena and the Hudson Valley in New York.

The civil engineering ingenuity involved in building these projects should not be underestimated. Chris Marshall is Britain’s road expert and reminds us about the M62:

Scammonden Dam on the M62, and the bridge crossing the motorway just next to it. The motorway passes through a man-made cutting, which is not unusual, but the scale of this particular one is in a league of its own. The material excavated from the cutting was used to build a dam, big enough to carry the motorway on top, which holds back a reservoir a mile in length that swallowed a whole village. The cutting is so wide and so deep that, when it was built, the bridge spanning it was the longest single-span non-suspension bridge in the world. The bridge is simply there to carry a B road. It’s a motorway built with enormous effort and ingenuity across more unforgiving terrain than any other road in the UK, and as a feat of civil engineering it deserves far more recognition than it ever gets.

Sainsbury’s, Camden, UK

SPEED

With trains the world speeded up, with cars it speeded up more. Now we were passing through space at a more and more frantic rate. Eventually speed limits were the end result. The fact that the built environment, like the countryside, flew past at a rate of knots changed our perception of buildings. Architects responded with kitsch flourishes to grab a driver’s attention.

The elastic change in time the car brought about meant that we could commute. We could live further and further from our jobs – not in the next shabby street next to a factory. Cities could then be zoned with housing away from industry, commerce and retail. And new cities could emerge, their neighbourhoods connected by highways.

It was inevitable of course that once fast cars appeared people would try and race them. The boy racers on country lanes became the bored lads speeding along Belle Isle Road or around Chelmsley Wood and Nechells Parkway.

When this was formalized it was obvious that motor sport’s drama was going to be a big draw. The AVUS circuit in Berlin, Goodwood, Monza – the motor-racing circuits became huge entities, and Formula 1 in particular has kept reinventing itself to become a global phenomenon. Monaco’s street race is the cordon bleu – the strange experience of being there, though, is glimpsing just a flicker of something between the fences, not really sensing the track entirely. Even at a conventional circuit the experience is intense and jarring – the extreme noise and not knowing who is where. Birmingham famously tried to recreate this as the ‘Monaco of the Midlands’ in the late 80s – turning over their ring road and streets to the racing cars.

Unsurprisingly, TV lapped up this hobby. Murray Walker’s voice commentating on Prost versus Senna is a memory that will never leave me. The newer circuits have been designed as beacons of modernity really – the Formula 1 brand of luxury, drama, speed, skill, precision – these are what Jeddah, Bahrain, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Austin, Baku, Abu Dhabi, have wanted to be aligned with. The legendary circuits like Le Mans (home of the 24 Hour race) and Spa have deep histories.

Those who like to speed know that German autobahns almost alone have no limits. Elsewhere the speed camera, or ‘radar’ as it’s known in many European languages, has kept us in check – that yellow or grey camera on a pole or mounted above the road, a symbol like the CCTV camera and intelligent display of a tech-oriented road of the future. Purists eschew this surveillance and enjoy the German road with its noticeable lack of clutter and tech.

BUSES

The car was glamorous. At least it was supposed to be. The bus? Not quite so much. But it’s cheap (sometimes), cheerful and gets the job done. All kids get the bus – to school and on school trips. You learn about exploring and bravery from bus journeys, not from being driven round in mollycoddling mums’ SUVs. The school trip is always by bus. When the railways and streetcars/trams were on their way out, they were replaced by buses.

The feeling was the bus could be a more efficient form of transport than trams and trains – the bus could go everywhere the tracks could not. Uh-oh. That went well – because buses, alas, are not as good as trains. They’re still great, but trains are better, trams too. Look at the dozens and dozens of cities trying to bring back tramways removed in the haste of the car-crazy decades.

This streetcar conspiracy was ridiculous and, yes, we have learned many times it was of course perpetuated by our old friends the auto, oil and tyre lobbies. Some architectural gifts were given among the scandalous wastage. Busáras in Dublin; Derby and Preston’s bus stations. Tel Aviv’s is too much but cannot be missed. The Port Authority Bus Terminal? Well, it’s hair-raising, but then so much about life in New York is. Victoria Coach Station in London came with art deco glamour when it opened.

The Eastern bloc bus shelter became a cult with its own books. Canberra’s cute bus shelters became an icon of the new city. The bus lane became a symbol of segregation on the road – an attempt to make the experience of sitting on the rickety bus a little less annoying. The guided busway or bus rapid transport tried to elevate the bus to almost the level of the tram. Adelaide’s O-Bahn sails through a river valley on a concrete track that made me think of a Disneyland experimental transport system when I saw it.

Latterly the bus has made a comeback. Skopje bought bright-red double-deckers like London. Manchester has taken its buses back into civic hands and painted them all yellow.

Of course, some people didn’t used to even buy a bus ticket, and hitchhiking – its hopeful participants gathering on the roundabouts and junctions at the edge of towns eager for a free ride – has come and gone in the UK. In many countries hitchhiking is still a run-of-the-mill way of getting around. Apps like BlaBlaCar have even projected a kind of 21st-century hitching into our data-driven worlds.

WHAT WE SAW

The signs that point us towards places lose their importance as times move on and we are guided ever more seamlessly by computers. Signposts, tag-teamed with maps, used to be the only way to know where to go. Reading a map was an essential skill. Everyone had an A–Z street atlas. The general road atlas sold by the bucketload and one sat on every passenger seat when the route calculations were something you did yourself by looking at the roads towards your destination. Thinking in 2D and 3D were great skills. Driving involves numerous calculations and that’s why it is a process that can probably be fully automated. But those maps were also things of beauty in their own right. The shapes of the cities and the lines the roads followed across the country were fascinating to behold.

Port Authority Bus Terminal, New York City

THE COUNTRYSIDE

Rural locations lost their rail connections, while some places are so remote or so underpopulated they never even had that. Cars were the new horses. It seems barmy that our tarmac arteries connect almost everywhere – largely funded by the state. Growing up in the countryside, rural roads were the connective tissue between places and people. The things you see – the old signposts, the wiggly lanes, the sunken roads bearing witness to hundreds of years of travels, the coaching inns, the blind summits and dangerous junctions – are testament to a world remade for the driver. Every house now with a garage and a car in the drive, whether in the real country or the suburbs that pretended to be the country and which architectural critic Ian Nairn railed at in the 1950s.

The rural petrol station with one pump, the passing place, the drunk drivers (no taxis), the tractors, the harvest, the hedgerows. And the main roads that pass through the rural idyll, bringing the metropolis with them: the noise, the lights, the signs, the bridges and underpasses. From the main road slicing through the pastures you can spy a countryside that seems like a theme park but is far more serious. And the main road brings its own architecture to the countryside: the service station, the picnic spot, the strip mall and the retail outlets at junctions, out-of-town office parks and supermarkets.

Bypasses bring the road into the fields – the village or the town gets its streetlife back but the people living on the peripheries now have cars at the end of their gardens. (One of the weirdest bypasses ever built is the Cinta Costera viaduct, which loops round Panama City’s old town out over the ocean on stilts.)

CITIES

Whereas the car makes a sort of sense in the country and other options are limited, the city was always going to be a bigger problem. You see the traffic jams in cities with incredible public transport like Brussels, New York, Munich and Paris and wonder why there’s even a car there at all. Trains, trams, buses, bikes, walking: the country doesn’t have these options, but the city does. How did we get here?

The planners thought the car would simply be everywhere and that everyone would have one. You watch the documentaries from the 60s that talk about cities having their arteries clogged but their solution is not give up the fags, booze and burgers – it’s install more arteries so you can do all those things even more.

The planners assumed that we would simply have to rebuild the city for the car. And if that didn’t work we would build new cities like Brasilia and Cumbernauld and Chorweiler and Louvain-la-Neuve and Milton Keynes and the deadening sprawl of Halle-Neustadt (aka Ha-Neu for the jokers) that were specifically designed for drivers, even though the East German citizens had to patiently wait for their awful Trabbie.

The city was changed beyond all recognition. The carchitecture age (‘carchitecture’ being shorthand for the car-centric architecture we saw emerge in the 20th Century and even more rapidly in the post-WWII world) brought in the one-way system, the gyratory, the urban motorway, the traffic light. Then it was the speed camera, the number plate recognition camera, the Black Mirror monitoring of the whole system. Roads cut communities as well as linking others. The Joy Division bridge in Manchester, where the band were famously photographed in the snow, bridged a chasm created by a new road, by a new world: the image and the music represented the nihilism of the new isolated age.