19,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

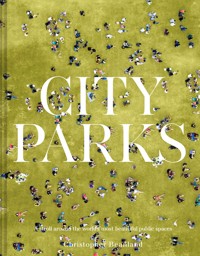

A visually stunning and beautifully written celebration of park life around the world. Parks are an absolutely essential part of modern life. From the author who brought you Lido, here are 50 of the world's greatest parks – but not just a list of the examples we already know. Yes, we'll tell you about those storied greats such as Central Park in New York and Phoenix Park in Dublin, but we'll also take you to the Philippines, to Australia, to provincial Britain and around the world to show you the most historic and the most interesting, the newest and most cutting-edge that mix the best of nature and architecture. We'll explore what you can find there, who goes there, why they are important, and how parks respond to their environments, including ones over a road, on old rail lines or in Berlin's former airport. Examples include: • Freeway Park, Seattle, USA: a bizarre and brilliant brutalist park over a motorway. • Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo, Brazil: this one contains amazing galleries and theatres. • Holyrood Park, Edinburgh, UK: mountains within a city. • Adelaide's parks, Australia: unique in that the entire city centre is enclosed by parks. and many, many more. Illustrated with glorious photographs throughout, this book is a fascinating record of the world's most interesting and innovative parks, and the people who use them – you'll want to visit them all.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

UK and Ireland

Europe

Americas

Asia

Africa

Australasia

Index

Hyde Park, Sydney, Australia.

Introduction

Play is the sine qua non of the park. This is the very quality missing from a modern life where we do too much, where we are too much. We sit and type, stand and talk, generate increasingly pointless plans and policies as the ecosystem collapses around us like a multistorey car park made of French toast, achieving nothing of note, scarcely dreaming. And all the while our egos balloon like a greedy uncle at Christmas, and our selfishness expands as capitalism caters to our every fleeting whim. We burn cash on crap and fry our eyes staring at screens and pour sawdust and glue into our cereal bowls because we’re so tired. Even creatives who do have dreams end up running themselves into the ground, coughing up content to be packaged, streamed and consumed; they themselves consumed with their own Torschlusspanik at dusk when the work is not well received or – worse – never even greenlit. We’re stuck on a treadmill. Some adults stretch out childhood well into their twenties, thirties or even forties, taking pleasure in life rather than sticking rigidly to the very Anglo and slightly sad Brief Encounter model of stolid devotion. You can see the trend: the Superdry dads at surf camps, buggering off to Sri Lanka, younger girlfriend in tow, fuelled on Huel. But mostly we fall in line – eventually – to be good consumers and hard workers, the American model gone mad.

Children act as a wake-up call, they make you realize that it’s all as pointless as firing a pistol at an orange on a camel’s head; life’s travails will always be as increasingly bizarre as they are hard to get right. Kids focus the mind on the only thing that matters: people. And what’s the best thing that people can do? Play. Have fun.

Take yourself back to your first memories. I’ll bet a park figures, because the park is the first place we’re taken out of the house to, it’s the first in a series of adventures that get increasingly bananas through the teens and twenties, stopping off in bedrooms and at bonfires, in Croatia and Costa Rica, before existence goes grey and plateaus off into a weird simulacrum of what went before, to wit: marriage and our own parenthood, thence a comfy and steady decline hopefully marked by teas and not tears. We become our parents whether we want to or not, we become what we fear as teenagers, everything becomes the same. You instinctively want to give the gift of fun to kids like your parents gave it to you because fun softens the blows.

What is exciting in life is anything that is not the same. We cling on to that for a reason. Those first days out from the house in a pram, then a pushchair, then joyously and clumsily skipping, then on your bike with your first friends and scratched knees, each day more invigorating than the last, making sense of the world by experiencing and exploring elevates you. To learn things anew, as a child does, is to be freed from the quotidian prison of disappointment and sameness and to see everything with the brightness, contrast, volume turned up to max. This is what the park is about at a fundamental level: a way to experience urban life on a higher setting. The joyous abandon of the kids we see laughing so hard, with ice cream smeared around their greedy mouths, should be our impetus to remember the power of play and fun, its importance in our brief, flickering existences. And the park is where that force is deployed daily, in a safe and managed version of the almost-natural world where there are trees and shrubs but nothing that will hunt you, kill you and eat you (incidentally, one wonders whether this omnipresent natural danger is what slowly turned Australia into the biggest nanny state of all). And it’s all completely free to the user – taxing local residents a small amount pays the costs of proffering paradise.

Hofgarten, Düsseldorf, Germany.

There are so many things we think we are that we are not. Life plays tricks on us. Romantic love is portrayed as altruism and snugs, and yet the reality is often a bleak zero-sum game where we are simply slaves to our own conscious and unconscious desires. This is not great for those of us who self-identify as romantics. To love is actually to want. Is it to care? We are fighting battles against our genes, against millions of years of evolution, against ourselves even – the book Sex at Dawn brings the sorry house of cards crashing down around us. Only therapy can fix this. What else? We are not natural home dwellers, we are not natural TV watchers, we are probably not even natural monogamous parents. We have become such strange creatures: technology has, more and more, bashed our brains as Ballard and Brooker predicted and yet we, despite our iPhone addictions, are so close to the foxes who scrabble around for the bones in fried chicken boxes, who follow you home, who you can almost talk to and feel such an affinity with on foggy 1am walks home, as Fleabag does. The truth is more brutal, as Werner Herzog reminds us: we are beasts. Animals who copulate indoors (the best thing that can be said for being inside, I guess). Animals are supposed to be outside. However, the many years we spent outside before architecture was ‘a thing’ has not disappeared from our synaptic receptors. It’s still there. You only want to sit inside watching Netflix on cold Northern Hemisphere nights. But to be outside, well, that feels much more right.

Why do we dream of the mountains and the lake and the beach? Because we belong there, not on suburban housing estates, not in petit Parisian apartments where you can’t swing un chat and you’re f***ed if you fancy cooking up Pommes Anna on your one-ring hob. Housewives, shuttered in their kitchens, shunted to new towns or exurban estates in the middle of the 20th century, suffered depression. This is nothing new, women in a patriarchy will always suffer depression, but it showed us how wrong we were. We need people, communities and connections, to be listened to, not to work every hour that God sends, to remember to enjoy life like kids enjoy life, to grasp each second on this out-of-control, overheating rock hurtling through space as if it were our last, to go outside to the park and see the beauty in buttercups and daisy chains and playing tag or throwing a ball about, to stop and take a mental picture when we’re picnicking with friends and realize that this is what human life is about – to be free, to be happy, to have fun, to be outside in the sun listening to Wet Leg on Spotify and the sound of the sparrows singing, to know that when the grisly and inevitable end comes it will have been a life, however short, well spent. Do not hesitate to skip lectures, to call in sick for meetings, to go and sunbathe in the park, to tell a person you are there with that you love them – and that you actually love them, you don’t just want to possess them. Go and do some sport: jump in the lido, play tennis, get the cricket bat out of the cupboard, unpack the cornhole set and wonder what the f*** the rules are. Grab life by the lapels – it is short, all too short. Life feels real when lived in 3D, feeling the breeze and the hot sun, listening to shrill laughter and birds, tasting cold ice cream and tepid cava. This is not trite spin whipped up in the overcooled office of a lamentable 360 marketing agency on the Lower East Side; I’m telling you what the ingredients for a happy life actually are. But then you must ask yourself if you trust a writer; for we make the fake look real and sometimes the real look fake.

Like writing, city life is artifice, architecture is mostly a sham; to paraphrase my coolest politics lecturer Dr Ricardo Blaug: the whole world is a stage set that could collapse at any moment (as it has done to those unlucky enough to live in Ukraine, Syria, Ethiopia, Venezuela ...). People in the city are all social climbers – watch out. Are parks exactly what they promise us, or are they bullshitting too? Parks are not the beautiful wilderness that we really crave but nevertheless they will do the job of being a temporary sanctuary, just as we dream of a movie star but marry a mortgage advisor. We accept (some of us) that what’s not quite perfect will be okay. Sold out of chocolate chip cookies? Get the hazelnut ones instead then. The realization that perfectionism will make you unhappy is an education that comes as one matures. The park gives us a taste of the natural world, a preened and primped world where the grass is cut and the flowers are arranged in some kind of crazy pattern. Herzog would never accept this distorted view of nature because it is too safe, too cultivated, totally inauthentic. Of course, the national park beats the city park just as the mountain lake beats the municipal lido, but one is a once-a-year treat, the other is there for us day in, day out. Yosemite, Death Valley, the Lake District – the dream of the Scottish naturalist John Muir brought to life in a way that emphasizes the white male predilection to own and dominate on one level and yet affords easy access to the beauty of the landscape for so many of us who love to walk the hills. But these landscapes too are built on the lies of terra nullius, and are faked and primped as well. The real countryside of farms and fields is often less pretty and less kind than city folk envisage (ask those who leave the city for the country what the reality is – no, the locals do not like Londoners, I’m sorry to break it to you). And country life itself is not like a glossy magazine despite what the travel industry wants you to believe. Yet ... for the majority of city dwellers around the world the fakeness of the nature in the national or local park is still okay, it will do.

Gardens are our own micro-version of this idea and loved, of course. How could you not relish a private outdoor sanctuary and the chance to watch your creations blossom and bloom? But they themselves are even more of a fiction, a product of a disastrous suburbanization that has cost the planet dear by making us reliant on the car. Ian Nairn was right to lament the semidetsian suburbs. LA is as compelling as Reyner Banham showed us in his 1972 BBC travelogue, its pools especially define it; its garden-based urbanism comes at a high price though – air pollution and constant jams on Interstate 10.

Jardin des Tuileries, Paris, France.

Today’s cities can’t stop building parks. They began as municipal undertakings that were revolutionary. ‘This could be my Hoover Dam,’ says Amy Poehler in the always hilarious Parks and Recreation, when her city council clown Leslie Knope is proposing a new park on Lot 48. As with everything else that the modern era provided us with, and for which we’re not grateful enough, parks were a plaything of the rich at first. As eventually bathrooms, decent housing per se, personal transport, good food and the rest of it trickled down from the powerful to the poor, so did parks. Aristocrats modelled the gardens of their stately homes after the enclosed hunting grounds that had for centuries allowed white men to do what they seemingly were unable to stop themselves doing: chasing animals and killing them. Many of both types – gardens and hunting grounds – became public parks as a sop to prevent the working classes from fully revolting: the former at Charlton, for example, and the latter at Hampton Court.

Paris’s Jardin des Tuileries dates from the 1500s and Boston Common in the USA and London’s Hyde Park from the 1600s. England was also where some of the first proper public parks were developed from scratch – Liverpool’s Princes Park of 1842 and, across the Mersey, Birkenhead Park in 1847. Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York’s Central Park, visited Birkenhead Park and it’s plain to see in the map of the park that its design – with lakes, ornamental structures, carriage drives, lawns and copses – looks strikingly similar to its Gotham cousin. Parks followed in all the great cities of the world, and then in virtually every town too. The Royal Parks of London, like Green Park, Greenwich Park and Richmond Park, were symbolic of a democratization of land, the first such move since enclosure had taken away common grazing rights and turned the world on its head in the Agricultural Revolution. Stately homes in the country would eventually almost always open their doors to the great unwashed, something unthinkable for centuries. Hyde Park was not unique in allowing free speech at Speakers’ Corner, but it is the most famous example, where today a plethora of serious and bonkers views can be expressed.

It was the Industrial Revolution that brought the need for city and town parks to the fore. Mass migration had created urban areas that were not fit for purpose, people were living like rats in rookeries. Parks gave them air and space and the opportunity to play. If we think we work too much now (and we do, especially in America), look at how bad it was for Bradford’s teenage wool factory inmates and Manchester’s cotton brethren locked into a cycle of toil that Engels and Marx saw as the powder keg it so obviously was. Parks were humane, they gave us the chance to be human.

Modernism made us think more about health, the 20th century – the People’s Century – brought sport to parks. Football, rugby and cricket stadia were built, cyclists appeared and, much later in the century, fun runners, and yoga practitioners and PTs with their high-paying victims wiggling arses as hard as teak. When I wrote my 2020 book Lido – about the history of outdoor swimming pools – I again ended up in many parks, because many parks were chosen as the perfect site for a pool: McCarran Park’s pool in Brooklyn, Wycombe Rye Lido in High Wycombe’s The Rye, London Fields and Brockwell and Parliament Hill Lidos on the edge of their respective London parks, the pool at Victoria Park in Sydney, Sommerbad Kreuzberg in Berlin’s Böckler Park. The park and the lido go hand in hand: both signifiers of civic and personal virtue, both fun palaces, both codifying fresh air and exercise too.