21,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

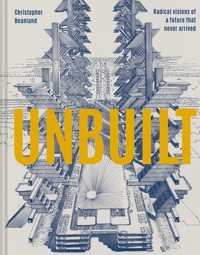

Unbuilt tells the stories of the plans, drawings and proposals that emerged during the 20th century in an unparalleled era of optimism in architecture. Many of these grand projects stayed on the drawing board, some were flights of fancy that couldn't be built, and in other cases test structures or parts of buildings did emerge in the real world. The book features the work of Buckminster Fuller, Geoffrey Bawa, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Archigram, as well as contemporary architects such as Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, Will Alsop and Rem Koolhaas. Richly illustrated with photographs, drawings, maps, collages and models from all over the world, it covers everything from Buckminster Fuller's plan for a 'Domed city' in Manhattan to Le Corbusier's utopian dream of skyscraper living in central Paris, from a proposed network of motorways ploughing through central London to a crazy-looking scheme for 'rolling pavements' in post-war Berlin. This is an important book, not just for the rich stories of what might have been in our built world, but also to give understanding to the motivations and dreams of architects, sometimes to build a better world, but sometimes to pander to egos. It includes plans that pushed the boundaries – from plug-in cities, moving cities, space cities, domes and floating cities to Maglev, teleportation and rockets. Many ideas were just ahead of their time, and some, thankfully, we were always better without.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 133

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The North–South Axis of Welthauptstadt Germania (see here).

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. POWER

Birmingham Civic Centre

The Bruce Plan

Pittsburgh Civic Center

Los Angeles Civic Center

Alternative Plans for Canberra

British Embassy, Brasilia

Germania

2. PRESTIGE

Berlin’s Post-war Rebuilding

Plan Voisin

Palace of the Soviets

Tokyo Bay Plan

Will Alsop in Yorkshire

OMA’s Vertical Cities

Louis Kahn in Philadelphia

Three San Francisco Plans

ESSAY: Oversized Art and Mad Monuments

3. CULTURE

Singapore Cloud

Modern Art Museum, Caracas

Herbert Bayer’s Bauhaus Kiosks

What Might Have Become of Sydney Opera House

Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood

4. CONNECTIONS

Motopia

Plan Obus

Leeds Levels

Pedways

Ringways

Cape Town Foreshore Freeway

Bering Strait Crossing

LOMEX

ESSAY: Representing Unreality: Collages, Drawings, Visions

5. HYPERMODERN MOVEMENT

King’s Cross Airport

Sheffield Minitram

Aeroport Mirabel

Maglev

SkyCycle

6. NEW CITIES

Civilia

Dongtan

Broadacre City

Minnesota Experimental City

Hook

La Citta Nuova

ESSAY: I’ve Started So ... I’ll Never Finish?

7. URBAN FANTASIES

Manhattan Dome

The Skopje That Partially Was

Ville Spatiale

City in the Air

Zaha Hadid’s Visions

Super-tall Skyscraper Cities

Helix City

Archigram’s Projects

No-Stop City and Continuous Monument

About the author/Thanks

Picture credits

Bibliography

Index

Rolling pavements: a vision for post-war Berlin (see here).

INTRODUCTION

Every human life is a series of failures. Every night we dream, every morning we plan. Everything is seemingly up for grabs. Everything we want, everything we crave. A whole world of everythings. ‘Everything means nothing to me,’ sang Elliott Smith. One day we go up in smoke or down into the ground, having achieved a fraction of the things we set out to – the ambitious and the creative will have done slightly more than the average.

An architect or a planner’s life is this model but supercharged – many will never see a single design downloaded from brain to earth and remade in three dimensions, most will manage a few, some will give up altogether. It’s very rare to be able to build a lot, rarer still for what you make to be what you want to make. Buy an architect a drink and listen to the reality, their reality: half of them draw up crap for money and are as disillusioned as a duck stuck in a car park. Most of what’s on the books is the meat-and-potatoes stuff no book will ever discuss: the endless faceless flats, the big-box retail, the budget hotels.

The few lives we celebrate are akin to the few buildings and plans we celebrate – the rest is a mediocre mess, just a lot of stuff in the middle. ‘Every life is both ordinary and extraordinary,’ mulls Logan Mountstuart in William Boyd’s Any Human Heart, a novel that distils the elemental essence of what life actually means. Mountstuart keeps dreaming, keeps trying; a lesson for us. Each loss, each failure, is just a necessary part of life. ‘A horrible thought: could this be the pattern of my life ahead? Every ambition thwarted, every dream stillborn?’ To be in a position of being able to dream, to try, to express one’s creativity, is a privilege, particularly a Western middle-class privilege – though not a privilege that’s particularly well paid until one clambers to the top of the greasy pole – brickies legendarily out-earn junior architects. Everyone out-earns writers. What do we want from a society? Evidently people good with their hands, celebrities, estate agents and yet more hedge-fund managers.

‘A little less conversation, a little more action,’ sang Elvis. It could be the architect’s theme song. For so much is a discussion, a proposal, an attempt. Even when the t’s have been crossed and the i’s have been dotted and the foundations have been sunk it’s no guarantee that the project will be finished. Look at the things that never got completed, like Watkin’s Tower in Wembley or the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow.

Most ideas don’t get this far. Maybe 90 per cent of what architects do is some level of theorizing; 10 per cent involves donning a hard hat. The hard hat is so seldom worn that the on-site brigade can easily spot how uneasily the yellow plastic crown sits atop the pate. That’s the architect – we could just look for the one person wearing all black instead (good luck trying that ruse in Berlin though).

Architecture is an ideas business, a words and drawings business, a thought business even. The attempt is to improve. To improve one has to innovate. Innovation doesn’t sit well though, least of all in Britain where the Second Industrial Revolution petered out decades ago, where an entire manufacturing industry is put in museums and where the modernist behemoths of the 1950s to the 1970s have mostly been knocked down. On Sunday afternoons we drive the car to famous buildings from well before that fecund period and admire them, then we drink tea and eat scones and reflect on what we’ve seen while we read recipes and interviews and blind-date aftermaths in the supplements. Maybe we should be visiting the archives instead and looking at infamous sketches of buildings and admiring them and wondering why they exist on paper rather than on the skyline. We fetishize what’s been done, we worry about what’s yet to be done and we ignore what’s not done. Innovation comes from the latter two.

Turning theory into built reality is a fag, yet it’s not as complex as Robert Hughes’s assumption about art: that the artist turns feeling into meaning. That is alchemy. Architecture is craft – far from easy, but with a set of rules to follow, parameters, guides, regulations and a huge amount of (as with films and publishing – thanks, editors!) unrecognized teamwork alongside the auteur. Anyone who labours under the misapprehension that that one ‘starchitect’ designed that new museum you enjoyed fleetingly is barking up the wrong tree, just as the idea that I am the sole person involved in getting this book into your hands is meretricious. An artist has a patron but doesn’t have to take as much shit from them as an architect has to take from a client. But then an artist is a genius (well …) and an architect a realist (well, mostly). When we talk about failed architecture, how often is it the client who has lost faith, cut corners, slashed budgets, failed to get ‘buy-in’ from ‘stakeholders’ to get things moving? Other forces can prevent the reality happening too: community action – which grew exponentially throughout the twentieth century, like environmental protest, locals saying no. It’s a valid point: no one wants things done to them. If a road is going to be ploughed through your park, or your favourite community centre is going to be bulldozed, you’ve every right to be pissed off about it. Add in planning controls, changes of political regime, changes of priorities, money running out, war breaking out, architects burning out, um … pandemics.

Architecture happens at a grandmotherly pace: it’s no wonder things slip through the cracks when the project you’re designing today may not top out for 10 years; much can change in the intervening period. It’s a wonder anything gets done.

If we’re discussing the unbuilt, we also need to remind ourselves that just because a building is built, its story isn’t over. When is a building finished? It is no more settled than we could say a human is finished when it arrives. Throughout the life of human or building many changes will happen – improvements, ill-thought-out renovations, degradations.

Architecture has sought to improve the world (mostly – ignore today’s rampant neo-liberal need for development dosh for a second). Theoreticians wanted something better. They’ve not always been listened to. Throughout history, from the first time we lined stones up, plans have been concocted – and although in this book we concentrate on the twentieth century, because the richest ideas of all come from that era, there are also instructive lessons from before the 1900s. Antonio di Pietro Averlino, or Filarete to his mates down the pub in Florence, was always on about his idealized city of Sforzinda in the 1450s. Moving beyond mere architecture, beyond one building towards building many, we see a long lineage of supersized visions that challenged the very way life was conducted. People have consistently sought to change the way other people behave. That process speeded up (as did every other facet of life) in the twentieth century. Example: the three-dimensional city idea that permeated like salad cream through Mothers Pride bread in the post-war world. The idea of putting pedestrians up above cars became a secular religion. The pedestrians in question never fully bought in to these doctrinal decrees, as the desire lines and vaulted barriers and windswept walkways attested to.

‘Place the city centrewhere maximum civicdrama might be achieved.’

KENNETH BROWN, INTRODUCTION TOHUBERT DE CRONIN HASTINGS’S CIVILIA, 1971

An alternative title for this book could have been ‘Maximum Civic Drama’. When the visions were so extraordinary and the world had reached the high point of social democracy, cheap energy and ambition during that golden age of the twentieth century – a state never to be returned to? – we saw expressions of unbridled creativity and flights of fancy.

After the Second World War the dreams were bigger than they had been at any time in history. And much was built with gusto and optimism and sometimes ignored humanism – as John Grindrod’s Concretopia outlines particularly well. Modernism unleashed a brave new world. There was, in Berlin, Tokyo and Coventry (among the many other cities ruined by the idiocy and violence that Ballard rightly pointed out was our defining human characteristic) tabula rasa which made grand projets possible; desirable even. These visions were sold as attainable utopias. OK, an idea is one thing, but words (how I wish this wasn’t necessarily so) alone don’t always pique sufficient interest. How else do you characterize what’s not there? In the era before the internet, World’s Fairs and Expos showed punters – who lapped it all up – what living in the future would be like. The national and corporate stands proffered dioramas, moving walkways, public art and Disney-engineered rides that showcased new worlds of automated cars, of multiple levels, of space travel and high-tech homes filled with gadgets. Films like the Eames’s explanation of how Saarinen’s Washington Dulles Airport would work with its mobile lounges ferrying lazy passengers to their planes or the many motor-industry movies like General Motors’ ‘Motorama’ showing automated cars expanded on what was, apparently, to come. Progress was everything, at all costs. It was accepted.

Dreamy visions of the future that would arrive (but didn’t) have become retro-futurist nostalgia – look at the video for Alvvays’ single ‘Dreams Tonite’, spliced together from snapshots of Montreal’s Expo ’67. We’ve never been more interested in past visions of the future and less interested in our future. Perhaps we’re terrified about what our future will bring. Sixty years ago we were being ushered into a future that brimmed – so the soothsayers said – with abundance and leisure (just forget about the nuclear bombs and you’ll be fine). Hundreds of record sleeves feature brutalist architecture on their covers (and Montreal’s Bucky dome; see locals Arcade Fire). Back in the twentieth century these visions were potent. Architects and planners had to sell their ideas, and many of those ideas sank. But even if they did, what we’re left with has a certain power – like Dieter Urbach’s collages of Berlin ladies basking beneath bloated blocks of Plattenbau. Sarah Hardacre’s modern-day mixing of modernist ‘eyesores’ with 1960s pin-ups makes you wonder what we’re more offended by now: high rise concrete utopias or bare breasts?

At Montreal’s Expo and Osaka’s in 1970 the dreams were the biggest of all. Architects and planners were at the high point of modernism, but they were also dancing on the deck of the Titanic. Their last big blowouts were the space-age propositions like the No-Stop City, which went on indefinitely. Megastructure projects had gone crazy in the 60s, buildings were getting bigger, cities were getting wilder. A cursory glance at any issue of Concrete Quarterly from 1964 to 1974 shows an almost unending series of ever more bulbous (which would be soon seen as bilious, sadly) projects, mouth-watering and eye-opening and utterly compelling. An interesting sidenote though: CQ regularly championed ‘streetscape’ and schemes that seemed to blend in with the environment, despite those very same projects being perceived retrospectively as being ‘too much’. They weren’t designed to be inhuman, on the contrary – that epithet was applied later, and not by everyone. The greatest period of building in human history, an epoch condensed to a decade, a brutalist blowout. Why not have a crack? If everyone else was building exciting things why not try too?

‘A wrong-headed hierarchy of realities grants primacy to a breezeblock over a painting of a breezeblock.’

JONATHAN MEADES

Sometimes you look at what was not built and you think it must have been a slender call – the girl that almost went on that date with you, the shot that hit the post, the exam you almost got a first in, the referendum that nearly went the right way – life’s ‘yeses’ and ‘nos’ are tighter than you could ever believe. Why do some things happen and some things not happen? We look for patterns, for certainty, for reason. The truth is that sometimes there is none. The belief is no longer in God or grand narratives (both can be pernicious; one has the possibility at least of making things better). Sometimes error, bad luck, a missed train, a bad mood, a storm, can change the course of the story. You can plan as much as you like (and hell knows architects and planners like to) but sometimes things just don’t work out. Why? Because life doesn’t always fall into place. Chance is much underplayed in philosophy. The flâneur recognizes randomness as essential, existential even. Architecture seeks to impose rationality on to chaos. Its end results sometimes create chaos where once there was simplicity. And with its journey being so meandering and messy it mirrors life. Guido, the exasperated film director in Fellini’s bravura 8½, could equally be an architect, just as the title of the movie could equally have been the original La Bella Confusione (‘The Beautiful Confusion’) because life resists attempts to shape it and sometimes one must embrace that and see the beauty in everything that can’t be controlled.

But we wanted to organize, to rationalize. We want to as humans. That urge has perhaps diminished today. It’s not entirely gone, there’ll always be a part of us like that – but we are more cautious. In the post Covid-19 epoch we are all scared little children, our sensitivity to risk shot. Everyone is paranoid – especially about each other. Planners were in the ascendancy in the twentieth century though, experts were, their expertise was. Patrick Abercrombie’s many and wholesale visions of London and especially its road network were radical. Like Abercrombie, many planners were sometimes also architects – look at John Madin’s failed vision of Madeley, later Telford – told in a dreamy, ruminative, fictionalized way by Catherine O’Flynn in The News Where You Are. Madin’s paymaster general in Birmingham was Herbert Manzoni, an engineer and the son of a sculptor who managed to push through a plethora of wild schemes that changed the face of the second city (though even he had a few plans he couldn’t get past the Corporation). In an era where you could build an enormous ring road in Birmingham’s city centre and erect dozens of brand-new towns in the English countryside, is it any wonder that planners were coming up with ever bigger and bolder schemes? They sniffed blood, sensed it was their time. So what if it never got built? It felt like it was the time to try. And even if not all of your proposals became reality (how many plans are left half-finished? – more than half, for sure) well, maybe you could get some of it built.

“After this, who believes in the idea of progress and perfectibility any more?”

ROBERT HUGHES ON LES TOURS AILLAUD, PARIS