17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

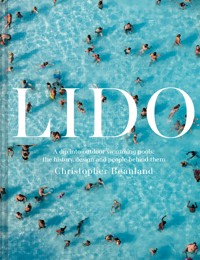

A celebration of outdoor swimming – looking at the history, design and social aspect of pools. Few experiences can beat diving into a pool in the fresh air, swimming with blue skies above you. Whether it's a dip into a busy and bustling city pool on a sweltering summer day, or taking the plunge in icy waters, the lido provides a place of peace in a frenetic world. The book begins with a history of outdoor pools – their grand beginnings after the buttoned-up Victorian era, their falling popularity in the 20th century, and the newfound appreciation for the outdoor pool, or lido, and outdoor swimming in the 21st century. Journalist and architectural historian Christopher Beanland picks the very best of the outdoor pools around the world, including the Icebergs Pool on Bondi Beach, Australia; the 137m seawater pool in Vancouver, Canada; Siza's concrete sea pools in Porto, Portugal; the restored art deco pool in Saltdean, UK, and the pool at the Zollverein Coal Mines in Essen, Germany. The book also features lost lidos and the fascinating history behind the architecture of the pools, along with essays on swimming pools in art, and the importance of pools in Australia. In addition there are interviews with pool users around the globe about why they swim. The book is illustrated throughout with beautiful colour photography, as well as archive photography and advertising.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

LIDO

LIDO

A dip into outdoor swimming pools: the history, design and people behind them

Christopher Beanland

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Pools

Britain’s Lost Lidos

What Pools Mean to Australia

Swimming in Art

Where to Find Them

Index

Introduction

To swim is to be reborn. Each dive into the water is a leap of faith. Each stroke draws you closer to some nebulous goal. Each breath reinforces your sense of sentient humanity. Swimming produces a new swimmer – a fresher, healthier, stronger, mentally cleansed version of the person who arrived with a head full of thoughts but will leave with only one: ‘It’s time to eat cake’. Literature, film and the therapy-soaked everyday lives of the Western middle class are all awash with the idea of renewal. By jumping into the pool you can often obtain redemption for the same price as a coffee.

Swimming is recreation as ritual. The imagery is obvious enough: water comforts us because it’s the nearest thing we have to being back inside the womb. The religious iconography of immersion and blessing is in play too. And maybe there’s something dragging us back to the time when our forebears first wriggled out of the sea and on to the land. Perhaps the water never left our souls when it left our lungs. The first public pool was probably the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro in today’s Pakistan. This 5,000-year-old remnant of that great city of the Indus Valley civilization looks, in many ways, just like today’s pools. The Greeks and Romans also swam and bathed, as did the Egyptians and Japanese. Ottoman hammams offered relaxation and 18th-century mineral spas in the Anglo and Teutonic worlds (Bath, Baden-Baden, Karlovy Vary) promised to cure ills before beta blockers and erythromycin. But until the 1900s swimming for fun was rare. Baths were primarily places to wash – the name has lived on in England’s northern industrial towns and England’s southern hemisphere colonies, where going to the baths today means going for a swim, not to wash. But those bath days were also time for a little relaxation in strained existences.

That mass washing of the 1800s and 1900s is worth noting because it laid a foundation for pool time being about leisure as well as lengths, about frolicking in the water too. Homes, Western ones at least, are all now built with bathrooms. But the camaraderie of bath day lives on at modern lidos where time by the side of the pool is as much a part of the experience as time in the water. Munching snacks, reading novels, painting nails and scrolling through dating apps are big poolside favourites today.

Competitive swimming grew in popularity throughout the 1800s, culminating in its inclusion in the Olympics for the first time at Athens in 1896. Frantic laps and race training became normalized at the pool. Slowly, pools also became places in which to get fit. The 20th century was in some ways the apogee of the swimming pool. The Victorians fetishized death and ignored sex. Now it was to be the other way around. Sex and exercise make you feel more alive than anything else. Trailblazers like Jersey’s 1895 Havre des Pas Pool kicked off this new era of pool building as the people’s century swept away millennia of stagnation.

Modernism, among its many and varied clarion calls, made the case for health and efficiency. The swimming pool was of course an intrinsic part of this: to be clean, lean, outdoors; for ordinary people to access exercise and enjoyment; for all this to take place in buildings whose form followed function; and where detail was sparing and well chosen. Especially in the 1920s and ’30s, public pools of an often impressive size sprung up hither and thither, like Lyons Pool in Staten Island, New York. Le Corbusier missed a trick – the pool squeezed into the middle of the rooftop running track on top of the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille is only deep enough for kids to paddle in, rather than people to dive into. Lubetkin made the pool at Highpoint in North London big enough for lengths, although it doesn’t quite have the wow factor of the pool for the penguins he designed at nearby London Zoo.

Art deco became a recurring theme of many of these endeavours, especially along England’s south coast in places like Saltdean, Penzance and Margate. The English seaside is that most perplexing of places – everybody goes there but no one swims in the sea. Pools next to the sea are strange. Pools play the essential role of sea-substitute in grossly landlocked cities like Almaty in Kazakhstan, where half the population will die without ever having seen the coast. Australian pools often featured brick buildings but reinforced concrete played a part in other places. Its influence was keenly felt with diving board towers, kind of proto-motorway sliproads in the sky. The boards at the Tropicana in Weston-super-Mare (which hosted Banksy’s satirical Dismaland exhibition in 2015) by H. A. Brown (demolished 1982), João Batista Vilanova Artigas’ brutalist 1960 platform in Rio de Janeiro and the diving board at the Tivoli in Innsbruck by N. Heltschl, from 1964, expressed their structural truism.

The last of the great modernist pools came with Brisbane’s Centenary Baths in 1959, with a Jetsons-style pavilion overlooking the water. Aussies never fell out of love with their pools. In Northern Europe and North America bathing beauties contests and packed pools gave way to bargain beach breaks that lured people to sunnier climes like Mallorca and Cancun in the Mad Men era, and strange social shifts took place. In the UK, the welfare state was at its high point in the 1970s with millions calling council houses homes and high-quality free healthcare for all. Yet, many lifestyles were far from healthy – with heavy drinking and smoking being the norm for some. All this, combined with a loss of faith in anything ‘municipal’ – and what were public pools if not that? – led to a slump and many closures throughout the 1980s. Their occasional replacements in the linen suit and cocaine age were the wave pools and leisure centres with slides – always at least partly under cover, as if swimming, like shopping, had moved from high street and market to supermarket and supermall – because we wanted to drive to both swim and shop, and stay dry when wet, apparently.

Things have changed dramatically today. Wellness is a new religion, 20 lengths before breakfast the natural corollary. Pools are cool according to the tiresome articles (oh wait, I wrote one) in newspapers’ glossy magazines (though when were they not?). In countries like Germany the tradition never really went away. Their (as the English would see it) pathological attitude to nudity and an Aufguss addiction, combined with everything else being shut on a Sunday, has always ensured a plethora of pool/spas doing business in every Teutonic town and city.

Like so much in the sphere of architecture, pools can convey a great deal. As with housing, they can connote elitism or democracy. Here we are concerning ourselves mostly, but not entirely, with public pools. Public pools are peoples’ spaces. That’s why they are busy. As with hotels’ eerie gyms, hotel pools are always empty, unless it’s August and you’re in a package holiday hotspot on the Mediterranean coast. Home pools’ emptiness is more spooky still – no wonder François Ozon was inspired to make his 2003 film dramatique,Swimming Pool. The drained backyard pool is a recurring image in J. G. Ballard’s writing. In the movie of Empire of The Sun, the empty pool is especially unforgettable.

But public pools stay busy. Rules are there to be followed. And like on trains, to wit there is a baroque performance where we learn how to interact and share space with strangers, sometimes in challenging, sweaty circumstances. The lifeguard’s whistle going off is the universal sonic symbol of an infraction; lane discipline, shower discipline, towel placement discipline, no ducking, no bombing, no horseplay, no petting. Australian writer Ellen Savage says this all ‘stands in for some of the more frightening elements of our rule-by-consent-of-the-ruled society’ in an article for Kill Your Darlings. She also wisely points to Michel Foucault’s idea of heterotopia, the weird world in microcosm. The lido is a perfect example of a heterotopia, sealed off from the outside world, yet of course open to the sky.

Pools were segregated for centuries. Women-only pools still remain, like in Coogee, New South Wales. But today the pool is the place you see the bodies of everyone and anyone in all their glorious individualism. Scars, scratches, fat, ripples, muscle, curves, hair, skin of every tone. The human body is as idiosyncratic and imperfect as every doctor dispassionately knows it to be. And the experience is the complete opposite of consuming media where bodies are shown as extremes of heaven and hell rather than as a weltering array of everything and nothing. Spectators outnumbered swimmers at lidos in the first half of the 20th century. Like the beach, the pool was the only place save for the art gallery where you could see the population’s bodies before society became saturated with selfies and porn.

Pools can be transgressive spaces too. Fashion often appeals to those most marginalized by the patriarchy – people who are queer, women, young people, people of colour; pools do too. Pools are not the places where middle-aged, middle-class men gather – they seem to prefer hobbies involving mecahnics and 0competition (so, okay, maybe you’ll see them triathlon training). This leaves lidos as free spaces where you will witness teenagers flirting, old ladies gossiping, freelancers scribbling, and more pregnant women than you’ve ever encountered in your life. If to swim is to be reborn, then pregnant women upend the truism by getting in there early. Pools allow adults to act like kids and kids to act like adults. Leon Kossoff’s paintings of pools in London show packed family fun days – they burst with vigour.

So, pools seem to be for everyone. But are they really? The lifeguards are from Colombia, the cleaners from Romania or the Philippines. The Welfare State in Europe was for the poor, but only the poor of rich countries who in the grand scheme of things were never doing that badly, with services staffed by those from former protectorates where the situation was worse. Public pools are only provided by governments in rich countries. Pools have been the site of racial conflict in Australia and the USA. In 1964 the manager of the Monson Motor Lodge in St Augustine, Florida, poured hydrochloric acid into the water when white and black students together staged an aquatic ‘wade in’, a watery tribute to Rosa Parks aimed at ending poolside segregation during the Civil Rights struggle. Swim Dem Crew and others have tried to mix things up more recently, to bring more swimmers of colour into the water in the UK.

In developing countries the situation is stark: 4 out of 5 of people can’t swim, versus 1 in 5 in the developed world. We luxuriate in pools while in Dhaka, Lagos, Port Moresby, Port-au-Prince and all the rest there are scarcely any. Drownings in the poorest and wettest countries like Bangladesh are sky-high because swimming is not taught. For those of us lucky enough to live in the First World, memories of learning are rich: diving to pick up bricks (why?) and wearing pyjamas to the pool – because sleepwalkers can drown too, right? I still have no idea how I ended up learning to swim in a pool on an East Anglian RAF fighter base with a full-size English Electric Lightning fighter aircraft poised on a plinth by the entrance, but the memory will never leave me.

For those of us lucky enough to possess a pool or live near one, the blissful experience of being in the water is almost transcendent on days when the sun lasers down, whether it’s a bracing winter dip or a cooling summer one. The world looks so strange when it’s full of reflections and refractions – the colours of the buildings and the birds and the aircraft and the sky all seem heightened. The rhythm of breathing and moving muscles takes you to a place beyond your usual self; the writer Joe Minihane makes a case for swimming as the ultimate mental health tool and after completing your lengths you’ll be hard pushed to disagree with that sentiment. The underwater world is a parallel realm of dreams and distortion and bubbles that you can enjoy until your breath runs out. Filmmakers, writers and artists have long seen the creative potential in this magical world. The introduction of Soy Cuba – the greatest opening sequence of any movie – delivers its jazz-soundtracked coup de grace when the camera descends into the rooftop pool of the Hotel Capri in Havana and gives us a fish-eye view that blows you away. The swimming pool has starred in underrated Aubrey Plaza comedy The To Do List, the 1970 Jerzy Skolimowski thriller Deep End and Guillaume Brac’s documentary L’Île au trésor.

Pools have inspired architects to produce great works – like North Sydney Olympic Pool by Rudder & Grout and Lucien Pollet’s Piscine Molitor, though more often the architecture is understated. Artists like David Hockney and Ed Ruscha have seen the potential of pools too. In the out-of-print 2005 book Liquid Assets, Tracey Emin says she wants to design a chain of pools along the River Thames in London. ‘They would be oval shaped, with an egg-like roof, which opens up when the sun comes out. And when that happened all the radio stations in London would make an announcement: “The London Ovals are opening!”’

Whether we care to admit it or not, a pool is a status symbol for an individual, a property developer, a hotel or a municipality. The pool as an Instagram sightbite is the predictable end result of this slippery process, the influencer as floating fodder for their own dreams of fame and fortune, their inflatable compatriot a unicorn or giant pizza slice. The infinity pool is the Patrick Bateman of swimming pools; the riad splash bath, the rooftop hot tub, the hotel horizon-chaser – images of instant gratification in our superficial, superfast world that ended up exactly as grubbily atomized as Ballard predicted it would. The pool on top of that oversized ironing table, the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore, is a bloated, bilious extravagance that can surely only be rivalled by a hovering pool held up by hot air balloons or a hundred drones.