13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

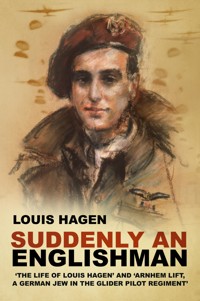

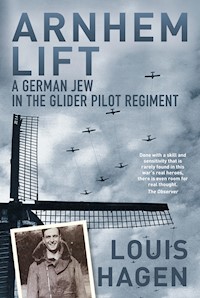

Of the 10,000 men who landed at Arnhem, over nine days 1,400 were killed and more than 6,000 – about a third of them wounded – were captured. It was a bloody disaster. The remarkable Louis Hagen, an 'enemy alien' who had escaped to England having been imprisoned and tortured in a Nazi concentration camp as a boy just a few years earlier, was one of the minority who made it back. What makes this book so unforgettable is not only the breathtaking drama of the story itself, it is the unmistakable talent of the writer. The narrative was first published anonymously in 1945.45 years later at a dinner party in Germany, Louis Hagen met Major Winrich Behr, Adjutant to Field Marshal Model at Arnhem. Louis added his side of the story to add even more insight to the original work.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To all who fell at Arnhem – Allied and German

‘I crawled right under the brushwood and saw and heard the bullets splashing the ground and hitting the branches and tree stumps all round me. I was sure this was going to be the end and kicked myself for doing such an idiotic thing; trying to take a strong German position on my own. I swore that if ever I got out of this hopeless position I would never again be such a bloody fool. I lay completely still, bullets whizzing about me. I wondered if I wanted to pray; that is what everybody is supposed to do in a position like this; but I just did not feel like it, and to calm and steady myself I watched a colony of ants go about their well-planned and systematic business.’

ABOUT THE BOOK

The action recorded here took place between 17 September and 25 September 1944. Arnhem Lift was first published in January 1945 (without the author’s knowledge!). Not only is it an extraordinary story, dealing as it does with a German Jewish refugee who ends up flying a Horsa into the disaster, it is also believed to be the very first book published about the battle – to the fury of the military and to great public acclaim. In 1950, Louis Hagen married Anne Mie, a Norwegian artist, with whom he had two daughters, Siri and Caroline. Dividing his time between London and Norway, Louis Hagen established Primrose Film Productions and went on to create 25 children’s films. He returned to Arnhem twice, first in 1948 to show his fiancée where he had fought, and again in 1994 for the 50th Anniversary. He had not planned to attend as he felt ‘the idea of parading with hundreds of old veterans like myself wearing rows of medals and red berets did not appeal.’ Louis Hagen died on 17 August 2000 at the age of 84. He rests at Asker in Oslo, Norway.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With thanks to Jean Medawar, my oldest friend, who first taught me to speak English, and now helped me to write it.

I want to thank my old friend Vivian Milroy for his patient help and detailed research into the strategies of the Battle of Arnhem.

I am grateful to my former ‘enemy’, Major Winrich Behr, for telling me his experiences at Arnhem and for letting me use them in this book.

Louis Hagen, 1993

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

About the Book

Acknowledgements

Prefatory Note to the First Edition

Foreword to the Second Edition

1About the Author

2The Background

3Arnhem Lift

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Monday

4Winrich Behr’s Story

5The German View of the Battle

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

6Summing Up

7Life After Arnhem

Epilogue

Plates

Copyright

PREFACTORY NOTE TO THE FIRST EDITION

When the author of this book arrived home on leave, after fighting right through the Arnhem action, everybody wanted to hear his story. After telling it several times, he began to find the repetition irksome, so he spent the rest of his leave writing it all down, while the events were still vivid in his mind. Any more friends who asked him for the story would get a type-written document! That is his explanation of how it came to be written.

Then someone suggested he should publish it. A copy arrived on my desk. After glancing through a few pages, I settled down to an absorbed reading of what I found to be a remarkable piece of reporting. Other urgent matters were left aside, and willy nilly I had to read on to the end. I believe that other readers will find it equally compelling.

This young soldier had no public in mind, beyond a few personal friends, when he set down his adventures. This may account for the intimate quality of his writing. But there can be no doubt he has a flair for picking out those details and moments which we all want to hear about – the touches of unexpected realism which help us to visualise and live over again the incredible heroic episode of Arnhem.

I have struck nothing quite like this diary for giving the actual feel and flavour of modern war at its most spectacular. This is the story of one man’s battle. It doesn’t purport to describe the action as a whole. It gives instead a series of ultra-vivid images and experiences. Like real life, it is inconsequent and surprising. It is also straightforward and free from egoism. In spite of the grim nature of the ordeal, the author seems to have come through with a sense of elation rather than with the despair and nervous exhaustion which the First World War seems to have produced in most of those who have written about it. This resilience gives an effect of balance and composure to the story, which is very remarkable considering the hectic and often horrible things that happen throughout it.

C.M., 1945

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION

This is the story of the First British Airborne Division’s great fight to hold the Arnhem Bridge as seen and experienced by a Glider Pilot.

It is my purpose here to paint very briefly the bigger picture of the Airborne Operations in Holland, a picture which only the gallant survivors were to learn from me when they returned to Nijmegen after their withdrawal from the Arnhem perimeter.

The Second Army was faced with increasing opposition by reformed German Battle Groups, in difficult country and with a series of water obstacles barring the way into Germany. Winter was approaching. The First British Airborne Corps (First British Airborne Division, 82nd US Airborne Division and 101st US Airborne Division) were ordered to seize and capture a corridor over 40 miles long which included the great bridges at Grave (River Maas), Nijmegen (River Waal) and Arnhem (Neder Rijn). The Second Army was to drive through this corridor and debouch into the North German plains, thereby turning the defences of the Rhine.

The Airborne Operation was successful in capturing the corridor and bridges, except for the essential gap between Nijmegen and Arnhem bridges. Owing primarily to the almost uncanny recovery by the German Army which had just suffered defeat in Normandy and on the Seine, and bad weather for air operations after the first two days, the Second Army were unable to reach Arnhem Bridge in time to achieve the complete breakthrough and the relief of the hard-pressed First Airborne Division.

This Division’s outstanding action and the successful operations of the two fine American Airborne Divisions, though failing in their final object of passing the Second Army through into Germany, ensured the retention and consolidation of the high ground at Nijmegen, pushed the Second Army, with incredibly few casualties, through over the 40 miles of difficult country and over two great rivers, and provided the springboard from which 21 Army Group launched its final assault on Germany early the next year.

Without the First Airborne Division’s heroic stand at Arnhem, which protected the northern flank of the battle and contained considerable German reserves, no such results would have been possible.

Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick A.M. Browning KBE, CB, DSO

October 1952

1

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

When I fought in the Battle of Arnhem, I was a lighthearted young German who had been born into a wealthy Jewish family of bankers. I had been brought up by liberal and devoted parents in idyllic surroundings near Potsdam, on the outskirts of Berlin, a lovely small town where the Prussian royal families had for centuries spent their summers in elegant and luxurious houses on the shores of Lake Jungfernsee.

Now I am an Englishman nearing 80, [Louis is writing this in 1993] still lighthearted, married, with two children and two grandchildren, living comfortably in Highgate, six miles from the centre of London.

This book tells the story of the events that were partly responsible for my transformation.

When I was a boy I was so full of the physical joys of life that I learned very little at school. I was more interested in ‘taking dares’. I was dared to come into class with a false beard, or riding on a horse. I was dared to eat a live frog. I did all these things, and my reports were very bad. My parents decided it was a waste of time to keep me at school. One day, when I was about sixteen years old, I heard my father say to my mother, ‘There’s no point in torturing the boy any longer. We’d better enrol him as an apprentice engineer.’ So I left school and went to start at the bottom in the BMW works, where my father and grandfather were on the board of directors. I enjoyed this new working environment and I learned a lot, without losing my high spirits.

One day I stupidly wrote a vulgar postcard about Hitler’s Brownshirts to my sister Nina.1 She left it lying around and it was picked up by one of the maids. This maid had been stealing my mother’s jewellery and was about to be sacked. She threatened to take the card to her boyfriend – who was one of Hitler’s storm troopers – unless my mother withdrew the accusation of stealing.

This was in 1934 and neither of my parents had any idea how seriously the new National Socialist authorities would treat the incident. So the maid was sacked; she went to her boyfriend, and soon after that storm troopers appeared at the BMW factory to arrest me. I was taken under guard and shut up in Torgau, an old castle which had been turned into a concentration camp. I was with a mixed group of men who were considered ‘racially inferior’ like Jews or Gypsies, or were thought to be politically dangerous, like communists and freemasons. The camp was run by Nazi storm troopers who enjoyed humiliating and torturing elderly Jews, or boys like me who had been brought up with more money and education then they had enjoyed. I was kicked off my straw palliasse in the middle of the night and made to crawl about naked on all fours while I was beaten for the amusement of the drunken guards. We had to empty latrines with our bare hands and carry the contents away in heavy iron containers that cut into the skin of our palms.

I was comforted by a fat, middle-aged communist called Wolfgang who became my friend. One day, while I was playing chess with Wolfgang, I noticed a group of men crowding round the window facing the courtyard. We got up to see what they were looking at but before I could get there Wolfgang pulled me back: ‘There’s nothing there, Budi. Let’s get on with the game.’ But I insisted on seeing what was happening: if ever I got out, I wanted to be able to tell people what was going on.

What was happening was the cruellest, most shocking thing I have ever seen. It was a very hot, sunny day; a group of SA men in shirtsleeves were standing round the farmyard pond where there were usually a few ducks swimming and a couple of pigs cooling themselves in the mud. There were neither ducks nor pigs in the pond, but instead four prisoners splashing around, entirely covered in mud, moving as if in slow motion because of its dragging weight. They were trying to crawl out of the pond but whenever they reached the edge, the SA men kicked them back in, laughing and shouting. I could not go on watching and turned away. Later I learnt that none of them survived.

When the guards could think of nothing better to do, they gave each of us a bucket of water, then chased us round the courtyard. If we spilt any, they beat us. I was young and very fit and I managed, but some of the older men were soon exhausted in the blistering heat and collapsed. They were then kicked and beaten until they got up and started running again. The weakest were chased into the muddy pond to ‘cool down’ before, covered in mud, they had to start running again.2

After six weeks of this I was rescued. One day, standing to attention in the courtyard, I saw the gates open. A large black Mercedes drove through, flying the swastika flag. In it was the father of one of my friends at school – a judge.3 I heard him ask for me. I was escorted to the guard-house where the Commandant informed me that if I ever revealed what was going on in the castle ‘We will get you, wherever you are, and bring you back, and then you will never get out.’

After my concentration camp experience my parents realised how dangerous it was for their five children to stay in Germany; my father thought it unnecessary, however, to make preparations for himself and my mother to leave. He used to say ‘This Hitler business is too crazy; it won’t last’. He thought the Nazis would not do anything to him because he had been decorated when a naval officer in the First World War and was head of one of the oldest and most respected banking families.

Arrangements were made to get me out of Germany as quickly as possible. It was not easy, in spite of my family’s many connections abroad, because at this time thousands of Jews were also desperately trying to leave. One country after another tried to control the flood of refugees from Germany; they all had problems with unemployment and were in a severe economic depression. It was almost eighteen months before a business friend of my father, Sir Andrew McFadyean, arranged for me to emigrate to England in January, 1936.

Sir Andrew, Chairman of the Liberal Party, was adept at getting German refugees into England: among others, he rescued the Hamburg banker, Sigmund Warburg, who founded the well-known London bank, S.G. Warburg. Sir Andrew managed to get me a job with the Pressed Steel Company at Cowley, near Oxford, which made car bodies for Austin, Morris and other British car manufacturers. I found that my apprenticeship at BMW helped me a great deal.

The job lasted almost three years. Then one day I was summoned to see Mr Muller, the Managing Director. He told me with some embarrassment that no foreigners were now allowed to work in factories engaged in war work; he had no option but to dismiss me. He assured me that he deeply regretted this because he had only had good reports about my work. He asked me what my private circumstances were and what I would do now. I told him that I had no family in England and no private money because my family were not allowed to send money out of Germany, and that my permit was valid only for the Pressed Steel Company. Mr Muller arranged for my salary of £3 per week to continue and promised that he would try to help me.

Ironically, only three years earlier the Managing Director of BMW, Herr Popper, had called me to his office and told me that one of the most embarrassing things he had ever had to do was to dismiss me – the Ministry of War would not in future permit ‘non-Aryans’ to work in factories producing armaments.

Mr Muller soon arranged for me to be transferred to the sales and service department of a subsidiary, Prestcold Refrigerators, in London. But when war broke out even this job folded because I was then officially classified as an ‘Enemy Alien’.

Now I was jobless I kept myself busy as a carpenter, building stage sets for small experimental and club theatres. I got hardly any pay and had to give up my flat, so I stayed with various friends and often slept on the stage wrapped in one of the curtains. I actually enjoyed this free and easy life.

I was of course elated at the prospect of the Nazis’ downfall and like most of my friends, I went to one of the many recruiting offices to volunteer for the army. An officer there told me that I would be informed when and where I was to join His Majesty’s Forces. As all the others who had volunteered were awaiting their call-up papers, I was not worried when I did not hear anything for a long time.

At last I did get a notice, forwarded by Sir Andrew, to appear at a tribunal to decide whether I was an anti-Nazi or a dangerous enemy alien, to be interned for the duration of the war. Sir Andrew offered to appear at this tribunal, but I told him I did not think this was necessary as my case was so clear – I was of Jewish extraction and had been imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp.

When I appeared at the tribunal, the chairman, before he even asked me to sit down, barked at me, ‘How is it you arrived here in your own car?4 You were supposed to report regularly to the police, not to be away from your home overnight and not to travel more than five miles from your registered address. You complied with none of these regulations and the police were only able to trace you through Sir Andrew McFadyean.’ He went on dressing me down for several minutes. Luckily for me Sir Andrew had decided to attend the tribunal and now offered to testify on my behalf. He said that he had known me and my family for over fifteen years, that I had no close family in this country and had only English friends, and therefore had not realised that aliens had been supposed to register with the police when the war started. His testimony saved me from internment – probably in Australia or Canada – and after a further strong reprimand from the chairman I was free, until my call-up, to return to my jolly life in the theatre.