33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

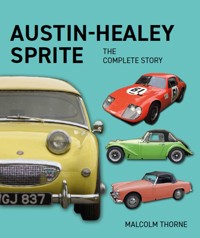

In May 1958, one of the world's largest motor manufacturers unveiled a diminutive two-seater that would take the world by storm. Small in stature yet able to punch well above its weight, the Austin-Healey Sprite rapidly gained an enthusiastic following among keen drivers, as well as an impressive record in competition. Being neither expensive nor exotic, for many motorists the Sprite opened the door to sports car ownership and, in so doing, its commercial success was almost guaranteed. With over 250 photographs, this book includes: the genesis of the Sprite, from the Austin Seven and pre-war MG Midget, via Donald Healey's Riley- and Nash-engined models, to the Austin A30, A90 Atlantic and Healey Hundred. The development, launch and market reception is covered along with details of the evolution from Mk I to Mk IV, including the Frogeye and restyled ADO 41. Rallies, racing and record breaking details are given as well as information on modifications, special-bodied variants, replicas and finally, buying and restoring a Sprite today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, 5, 6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupes 1965–1989 2000C and CS, E9 and E24

BMW Z3 and Z4

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ-S The Complete Story

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Fintail Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & Noakes SLC 107 Series 1971–1989

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era 1953–1998

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Carrera - The Water-Cooled Era 1998–2018

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800 Series

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI – The Full Story 1976–1986

Saab 99 and 900

Subaru Impreza WRX & WRX ST1

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Malcolm Padbury Thorne 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4052 4

DedicationTo Mari: friend, inspiration and co-conspirator, without whom none of this would have happened.

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Photographic creditsDouglas Anderson (pp.139 both); Chris Banton (p.50); James Barrett (pp.172, 174); Birmingham Museums Trust/Wikimedia Commons (p.9 top); Bonhams (pp.124 top left, 126, 148 bottom, 198 top); Keith Brading (pp.187 both, 188 both); Russell Filby (p.26); Paul Freeman (pp.140, 141, 168 top); Ford Heacock (pp.120 right, 178 top left); Philip Herrick (p.170 bottom); Peter Healey Photograph Collection (pp.21 bottom, 39, 197 top); Robin Hughes (pp.180 both, 181 both); Frontline Developments (pp.175, 176 top, 177; Halls Garage (pp.189, 1900 all); Harry Hurst (pp.126 top, 135 both, 137 top); Martin Ingall (pp.185 bottom, 186 both); Emma Jacobs (p.171); Tim King (p.170 top); Gary Lazarus (pp.145, 150, 161, 184, 185 top); Dudley Lucas (pp.127, 132, 133 top, 147, 148 top); Michael Malcolm (p.115 top); Bob Marshall (p.116, 130); Bob McClellan (pp.124 top right and bottom); Revs Institute, Albert R. Bochroch Photograph Collection (p.137 bottom); Revs Institute, Tom Burnside Photograph Collection (pp.108, 123); Revs Institute, Marcus Chambers Photograph Collection (p.107); Revs Institute, George Phillips Photograph Collection (pp.38, 113, 115 bottom); Ted Roberts (p.110); John Sprinzel (p.105); Karsten Stelk (pp.18, 120 left, 121, 128, 133 bottom); Paul Taylor (pp.192 both, 193); Thinktank Birmingham/Wikimedia Commons (pp.8, 14); US National Archives/Wikimedia Commons (p.13 top); Bruno Verstraete (pp.122, 156); Wikimedia Commons/zantafio56 (pp.129); Tony Wilson-Spratt (pp.117, 157 top, 162, 163 bottom).

CONTENTS

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE

CHAPTER 2 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 3 MK I

CHAPTER 4 MK II

CHAPTER 5 MK III

CHAPTER 6 MK IV

CHAPTER 7 RALLIES, RACING AND RECORD BREAKING

CHAPTER 8 SHAPE SHIFTERS

CHAPTER 9 HOTTING UP THE HEALEY

CHAPTER 10 THE GREATEST FORM OF FLATTERY

CHAPTER 11 BUYING AND RESTORING

Bibliography

Index

TIMELINE

22 October 1952

The Healey Hundred is unveiled at the Earls Court show, leading to the birth of the Austin-Healey marque.

Autumn 1956

Donald Healey and Leonard Lord agree to collaborate on the development of an entry-level sports car.

31 January 1957

The first Sprite prototype is delivered to Longbridge.

31 March 1958

After a false start, Sprite production begins in earnest.

20 May 1958

The Austin-Healey Sprite is officially unveiled in Monte-Carlo.

7–12 July 1958

Sprites take a 1-2-3 class win on the Alpine Rally.

1959

DHMC produces the XQHS Super Sprite prototype.

21 March 1959

Sprites take a 1-2-3 class win on the Sebring 12 Hours, Florida.

24 May 1959

The Sprite makes its debut on the Targa Florio, Sicily.

September 1959

The EX219 streamliner establishes a series of international Class G speed records at Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah.

13 April 1960

Sprites set speed records at Jabbeke, Belgium.

25–26 June 1960

The Sprite makes its debut on the Le Mans 24 Hours.

Autumn 1960

Work begins on the facelifted ADO 41.

17 September 1960

Sebring Sprite homologated by the FIA.

3 November 1960

Sprite-based Innocenti Spider unveiled at the Turin show.

November 1960

The final Mk I leaves the Abingdon production line.

March 1961

Production of Mk II (HAN6) begins.

21 May 1961

The Mk II is unveiled.

20 June 1961

The badge-engineered MG Midget is launched.

3 May 1962

Sebring Sprite Mk II homologated by the FIA.

October 1962

HAN7 replaces HAN6.

28 January 1964

Production of Mk III (HAN8) begins.

9 March 1964

The Mk III is launched.

1965

DHMC produces the WAEC prototype.

27 March 1965

The windtunnel coupé makes its debut at Sebring.

October 1966

The Mk IV (HAN9) is launched.

4–14 January 1967

A road-going windtunnel coupé is displayed at the London Racing Car Show.

January 1967

An additional temporary production line is set up at the Morris factory in Cowley.

November 1967

Revised specification for North American cars is introduced to comply with US regulations coming into force on 1 January 1968.

17 January 1968

British Motor Holdings and Leyland Motor Corporation merge to form BLMC.

28–29 September 1968

Final motor sport entry by a works Sprite: Le Mans 24 Hours.

October 1969

HAN10 replaces HAN9; the Sprite is withdrawn from export.

21 March 1970

The last windtunnel Sprite (TFR7 ‘BMC roadster’) makes its competition debut at Sebring, and HAN9-R-238 records a final class win at the venue (both as private entries).

31 December 1970

BLMC’s contract with DHMC expires; the Austin-Healey name is dropped.

27 January 1971

Austin-badged AAN10 Sprite enters production (UK market only).

7 July 1971

AAN10 production ceases; the Sprite name is dropped.

CHAPTER ONE

INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE

We are the biggest producers of sports cars in the world, and we see an enduring market for them in the USA … These are cars that the Americans just don’t make themselves.

Sir Leonard Lord, BMC World, September 1960

In May 1958, one of the world’s largest motor manufacturers unveiled a diminutive two-seater that would take the world by storm. Small in stature yet able to punch well above its weight, the Austin-Healey Sprite rapidly gained an enthusiastic following among keen drivers, as well as an impressive record in competition. Being neither expensive nor exotic, for many motorists the Sprite opened the door to sports car ownership and, in doing so, its commercial success was almost guaranteed. The greatest accolade, however, is that half a century after production ceased, the Healey remains as popular as ever, with owners including such luminaries as McLaren F1-designer Gordon Murray. Vindication, indeed, of the soundness of design.

As the name suggests, the little Austin-Healey owes its existence to two distinct firms: the Longbridge-based Austin Motor Company (by 1958, a division of the British Motor Corporation), and the Warwick-based Donald Healey Motor Company. It is with the former that the story begins.

SIR HERBERT’S BABY

Founded in 1905 by Herbert Austin, the eponymous automobile manufacturer unveiled its first models – the chaindriven, 5182cc 25/30, and the similar but smaller-engined 15/20 – early the following year. Although initial production would be little more than a trickle, by World War I the firm had gone public and lucrative military contracts led to exponential growth. By the end of hostilities, more than 20,000 people were employed at Longbridge, but following the 1918 armistice the firm struggled to find sufficient customers for its large and expensive models. Financial restructuring and a move downmarket meant that the company would survive, however, and in 1922 it launched one of the cars for which it is most fondly remembered today – the Seven.

Sir Herbert Austin was born on 8 November 1866.

Given the model’s phenomenal success, it may seem perplexing that Austin management should have been anything but enthusiastic about the Seven – yet the project initially met considerable opposition from the firm’s creditors and board of directors (who favoured larger machinery). Undaunted, the company founder pressed ahead, the car famously taking shape in the billiards room at Lickey Grange, his sprawling home on the outskirts of Birmingham, where he was aided by a young draughtsman named Stanley Edge.

Sir Herbert’s tenacity paid off, and the Seven would become one of the most iconic vehicles to emerge from the British motor industry during the interwar period – some 290,000 rolled off the production line between 1922 and 1939, as well as licence-built copies in France, Germany, the United States and Japan. Conceived as a rival to the ubiquitous motorcycle and sidecar, or the multitude of rudimentary four-wheeled cyclecars that had become popular at the time, at £165 in 1922 the Seven was little more expensive to buy or run. Unlike other offerings, however, it had the feel of a big car in miniature rather than an object of penitence.

The Austin production line at Longbridge, Birmingham in the 1920s.

A tiny car with a huge impact: Sir Herbert in an early Austin Seven.

Built on a simple A-frame chassis, the Austin was initially powered by a two-bearing 696cc water-cooled four-cylinder, although that was soon stretched to 747cc (meaning that for tax purposes, later Sevens were actually rated at 8hp). With room for a small family, plus a top speed approaching 50mph (80km/h) and the novelty of four-wheel brakes, the car decimated its competitors and would go on to be offered in a bewildering number of guises. From saloons to utilitarian commercials and even coach-built flights of fancy, there was seemingly a Seven for every occasion – and that included motor sport.

Seven saloons offered affordable motoring to a burgeoning market.

The idea of a racing car based on such humble underpinnings may seem anathema (early Sevens developed a meagre 10.5bhp at 2,400rpm), but the Austin was light in weight and fleet of foot. And with many events featuring a handicap system to level the playing field between large-engined thoroughbreds and smaller-engined tiddlers, the car was just begging to prove its mettle.

At Brooklands on Easter Monday 1923, a Seven with largely standard mechanicals won the Small Car Handicap at an average speed of 59.03mph (95km/h), while that September a streamlined single-seater driven by aviation pioneer Eric Cecil Gordon England established a series of speed records – including 5 miles (8km) at 79.62mph (128.14km/h). The Seven’s first season of competition was rounded off by a class win at the Shelsley Walsh hillclimb in Worcestershire.

As it evolved on the track (the most sophisticated Sevens would eventually feature a dry-sump supercharged twin-cam pumping out an astonishing 112bhp), so improvements filtered down to the buying public. Longbridge’s first in-house sports model amounted to little more than a standard open tourer with modified rear bodywork, but Gordon England’s twin-carburettor Brooklands two-seater was an altogether more exciting proposition and guaranteed to hit 75mph (120km/h) in racing trim.

By 1928, Longbridge had introduced a proper performance version of its own: the Ulster. Featuring a modified front axle to give a lower stance, plus a high-compression engine, closer gear ratios and skimpy two-seater body, for £185 the 24bhp, 952lb (432kg) flyweight was good for around 70mph (113km/h) – far from shabby for a 747cc sidevalve. For an extra £40, meanwhile, a Cozette supercharger boosted output to 33bhp.

Like its forebears, the Ulster proved to be a formidable racing car and in 1930 scored a number of significant victories – among them an overall win in the BRDC 500 Miles, as well as the 750cc class in the Brooklands Double Twelve. This was followed by a string of speed records – including an average of 81.71mph (131.5km/h) for twelve hours – while in 1931 one finished second in the 1100cc class on the gruelling 1,000-mile (1,600km) Mille Miglia in Italy.

The Ulster was a surprisingly effective miniature sports car.

Ulster production ceased in 1932, the 65 (or Nippy) and 75 (Speedy) taking over the baton. As the 1930s progressed the racing and record attempts would continue, and by the end of the decade Charlie Dodson had raised Sir Malcolm Campbell’s 1931 flying-mile benchmark of 94.03mph (151.33km/h) to an incredible 121.2mph (195.05km/h).

By the time the Seven was pensioned off in 1939, Austin had not only survived the economically turbulent interwar years but had cemented its position at the forefront of Britain’s motor industry. With the outbreak of hostilities, however, car manufacturing was curtailed as factories geared up for the war effort, while petrol rationing and the demise of Brooklands (which was turned over to the aircraft industry) put paid to any lingering notions of motor sport or record breaking.

THE MG MIDGET

Sporting variants of the Austin Sevens had many rivals on both road and track, but one of the most significant is the MG Midget, a name that would become indelibly linked with the Sprite.

The MG Car Company can trace its heritage back to 1923 when Cecil Kimber, the manager of William Morris’ Oxford-based Morris Garages, began offering stylish rebodied versions of his employer’s mass-produced models. As Kimber’s ambitions grew, his machines became faster and more elaborate, as well as more expensive, the handsome six-cylinder 2468cc 18/80 of 1928 retailing for a substantial £555. From 1929, however, a tiny two-seater would take the firm in a more financially viable direction.

The first MG to sport the Midget name was the Morris Minor-based M-type of 1929.

Based on the contemporary Morris Minor (an economy model conceived as a rival to the Seven), the MG M-type employed an 847cc overhead-cam Wolseley engine and was clothed in an attractive fabric-skinned boat-tail body. Priced at £185, it was a natural competitor to the Ulster and the first in a long line of MGs to use the Midget designation. It was replaced in 1932 by the faster and more rakish J-type, which in 1934 gave way to the heavier but very pretty P-type, while sophisticated racing specials included the successful supercharged 750cc ‘Montlhéry C-type.

Under the ruthless direction of Leonard Lord, the Nuffield Organization (of which MG was part) began a programme of rationalization and cost-cutting during the mid-1930s, bringing about the demise of the overhead-cam engines and exotic competition models, the T-type that replaced the P-type in 1936 being equipped with an overhead-valve Morris unit.

The TF was the last of the traditional square-rigged Midgets, and was retired in 1955.

Although T-type production was curtailed during World War II (during which time Donald Healey ran a modified example), the Midget is often considered the archetypal fighter-pilot’s car and certainly caught the attention of US servicemen stationed in the UK. That popularity, and the government-led export drive, encouraged MG to expand into North America after manufacturing restarted, opening up a vast untapped market for British sports cars. Without the success of those early exports, it is unlikely that the Austin-Healey marque would have been created, and without that there would have been no Sprite.

ENTERING A NEW ERA

Austin resumed civilian production in 1945 with a by then antiquated line-up of sidevalve models, but in 1947 unveiled its first post-war design: the A40. Available as the two-door Dorset and four-door Devon, the A40 was powered by a long-stroke 1200cc overhead-valve four-cylinder and, although relatively unloved today, it was enthusiastically received at the time. It was joined a year later by the larger and more expensive 2199cc A70 Hampshire, which in 1950 would evolve into the restyled but mechanically similar A70 Hereford. The big news, however, was the arrival in 1951 of a spiritual successor to the Seven: the A30.

Heralded by its maker as ‘the greatest achievement in post-war motoring’, the A30 was a curious amalgam of old and new: the bodyshell, for example, was Longbridge’s first unitary design, yet the hydromechanical brakes remained resolutely pre-war in concept. For all Austin’s hyperbole, the A30 was, nonetheless, a hugely significant machine – the most notable feature being its engine. One of the final projects undertaken by Austin before merging with archrival Morris to form the British Motor Corporation, the overhead-valve unit (in essence, a scaled-down version of the A40’s 1200cc lump) was initially designated AS3 or 7hp, but would soon become known as the A-series.

A40 Devons undergo final inspection at the Longbridge plant.

When Motor Sport tested an A30 in May 1953, the journal was full of admiration for the 803cc engine, prophetically saying: ‘It gains full marks as a very smooth and exceedingly lively one, which revs up like a sports unit in response to accelerator depressions.’ However, the authors were less convinced by the Austin’s handling characteristics, observing that the Morris Minor offered superior road manners: ‘[The A30] has a narrower track and is higher, so that steering it on a wet road in a strong cross-wind, or at its terminal velocity downhill, is rather like we imagine tightrope walking to be – all right if you keep going straight.’ In spite of such reservations, the writers summed up that the £355 saloon (£504 0s 10d with purchase tax) was the best model in the Austin range at that time.

Austin’s post-war replacement for the Seven was the A30.

If the A30 was the best, the A70 Hereford (which at £941 1s 1d, including tax, was almost twice the price) received a more subdued reception, with Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson openly attacking the six-seater’s road manners in his 1951 report: ‘With the high centre of gravity, the weight transfer under cornering is out of all proportion and produces a vicious roll-oversteer, which the steering ratio can’t cope with,’ he wrote, adding that ‘the pitch-free ride … is very good and beyond complaint, but this has been achieved by spring rates and suspension design that were never meant to be shown a corner.’

When considering such damning words, it must be remembered, of course, that these roly-poly post-war saloons were not conceived for sporting motorists. Unlikely though it might seem, however, they would be pivotal in establishing BMC at the forefront of sports-car production – but not before a couple of false starts.

THE BRITISH MOTOR CORPORATION

When Austin and the Nuffield Organization announced their merger on Friday 23 November 1951 to become the world’s fourth largest motor manufacturer, many observers would have been quietly shocked. The companies had always been fierce rivals, and there was a longstanding enmity between their bosses, Lord Nuffield and his former protégé Leonard Lord. However, the logic behind the move was simple: by coordinating their efforts, the firms (which in 1951 had a combined output of 240,000 vehicles and pre-tax profits of £17.5m) would dominate the British motor industry and benefit from greater economies of scale, with a corresponding increase in profitability. That, at least, was the theory when the amalgamation officially took place on 31 March 1952.

In practice, by merging the two empires (which then comprised Austin, Morris, MG, Riley, Vanden Plas and Wolseley), the resultant British Motor Corporation proved to be an unwieldy edifice with overlapping ranges, competing dealer networks, and a flawed business model. Notwithstanding, the company would continue to expand – acquisitions included body manufacturer Pressed Steel in 1965, as well as Jaguar in 1966 – and, thanks to engineers such as Alec Issigonis and Alex Moulton, would champion innovation. Ground-breaking front-wheel-drive saloons such as the Mini and 1100/1300 would become bestsellers, while MG and Austin-Healey made BMC the world’s biggest manufacturer of sports cars, enjoying unprecedented success in North America.

The corporation would, however, be remarkably difficult to rationalize, and attempts to do so were sometimes misguided. Although the implementation of the (small, medium and large) A-, B- and C-series engine families was a success, the badge engineering for which BMC became infamous during the 1960s was at best cynical – certain cars being marketed under half-a-dozen names with only superficial differences. Other models, meanwhile, were simply ill-conceived and unappealing.

Crucially, the sprawling behemoth would never achieve the commercial success envisaged at the time of the Austin-Nuffield merger and, in spite of production peaking at more than 730,000 cars in 1964 (a threefold increase in thirteen years), the corporation’s UK market share fell from 53 per cent in 1952 to only 30 per cent in 1967 – Ford, in particular, aggressively chasing BMC customers. Profits, meanwhile, fluctuated wildly, climbing from a pre-tax £12m in 1957 to almost £33m in 1960, before falling again to £11.5m in 1962.

By 1963 there were no fewer than thirty-eight cars in the BMC range, costing from £447 to £1,112.

An Austin-Nuffield merger was mooted during the 1940s but didn’t take place until 1952.

Vast though the conglomerate may have been, it was founded on shaky footings and by the late 1960s was in serious trouble – duplicated ranges, uncompetitive designs and short-sighted planning combining to create a cash-flow problem. Since before the Jaguar acquisition, management had been exploring the possibility of a merger with Leyland Motors (which aside from its core interest in commercial vehicles, owned Triumph, Alvis and Rover) and, in October 1967, at the behest of Prime Minister Harold Wilson, talks were intensified. The firms officially joined forces on 17 January 1968 to become the British Leyland Motor Corporation, but that in turn suffered financial collapse during the mid-1970s, leading to nationalization.

The restructured business later passed to British Aerospace, BMW, and finally the Phoenix consortium. During this time it was variously branded Austin-Rover, Rover Group, then MG-Rover, and numerous divisions (including Jaguar, Land-Rover and Mini) were hived off. Bankruptcy in 2005 led to its acquisition by Chinese-owned Nanjing and a relaunch as MG Motor. In 2020, the company accounted for only 1.15 per cent of the UK car market.

UNDERWHELMING AUSTINS

Six years of war had left the United Kingdom in a parlous economic state, and with Clement Attlee’s Labour government recognizing the urgent need for foreign currency, British industry was given a very clear message: export or die. With an eye firmly on the United States, Austin thus set about designing what it saw as an export-friendly model. The result would be the A90 Atlantic, a baroque six-seater convertible that made its debut at the 1948 Earls Court show; it was followed a year later by a similarly styled fixed-head derivative.

Based on the A70 and powered by an uprated 2660cc version of that car’s overhead-valve four-cylinder, the 88bhp Atlantic was found by The Motor to be good for 0–60mph in 16.6sec, and a maximum of 91mph (146km/h). In the context of the day, these were very respectable figures for a bulky machine that tipped the scales at some 3,000lb (1,360kg) – but once again, the handling was less convincing. In its October 1951 review, Motor Sport applauded the A90’s turn of speed, but was more sceptical of the chassis: ‘[It] covers a lot of ground in very little time,’ wrote the testers, before adding the caveat that ‘…its suspension is such that corners demand respect … This is not a car for the dashing to hurl round corners.’

While never intended for the track, the Atlantic was a rapid device under the right conditions, and the marketing men went to considerable lengths to prove it; in 1949 they dispatched an A90 to Indianapolis, where it set a remarkable string of speed records. Alas, US buyers had little appetite for pseudo-Americana – especially when equipped with a four-cylinder engine in place of the six- or eight-cylinder units that were the norm in Detroit. The Atlantic was a commercial disaster, only 7,981 finding buyers from 1948 to 1952 (of which a meagre 350 went to the United States).

Too few cylinders for America, and too brash for the UK: the Atlantic was a commercial flop.

In 1950, two years after the launch of the A90, the Longbridge range was expanded by the addition of another niche model: the optimistically named A40 Sports. Based on the chassis and running gear of the Devon, the car was clothed in aluminium coachwork that bore a remarkable resemblance to the recently introduced (and Austin-powered) Jensen Interceptor. The similarity was, in fact, no coincidence: the styling was by Jensen’s Eric Neale and, although final assembly took place at Longbridge, body production was also outsourced to West Bromwich.

The Jensen-bodied Austin A40 Sports.

In spite of its twin SU carburettors, the 46bhp Austin was more sedate tourer than rorty sports car, and its credentials were further stymied when the specification was revised in August 1951. Although visually similar, the second series was cursed with that most unenviable of 1950s fads: a column gearchange. This was mitigated by the adoption of fully hydraulic brakes (the original featured mechanical rear drums) but, better anchors or not, the woolly handling A40 was anything but sporting. In spite of a Longbridge-sponsored publicity stunt where Austin’s head of public relations, Alan Hess, drove around the world in twenty-one days, a scant 4,011 found buyers by the time the model was withdrawn in April 1953.

During their brief careers, the A40 Sports and A90 Atlantic had thus resolutely failed to inspire customers – but the 450,000 visitors attending the Earls Court show from 22 October to 1 November 1952 were greeted by the sight of a sensational new roadster that would break the Longbridge duck. Equipped with the A90’s torquey 2660cc ‘four’, the car was sleek, seductive, and as achingly beautiful as it was fast. It was not, however, displayed on the Austin stand.

THE BIRTH OF A MARQUE

Tucked away in a corner of the exhibition halls, partially obscured by a pillar, the Healey Hundred had been designed and built by the Donald Healey Motor Company of Warwick. Although the two-seater relied heavily upon Austin ironmongery, it was not intended to be a mass-market BMC product: created by a small group of engineers, including former rally ace Healey and his son Geoffrey, the Hundred (like its predecessor, the Nash-Healey) had been conceived to replace the firm’s Riley-engined models in the lucrative American market.

Slotting neatly between the 77mph (124km/h), 1250cc MG TD and the 124mph (200km/h), 3441cc twin-cam six-cylinder Jaguar XK120 (both of which were enjoying considerable success in the United States), the Hundred featured a welded-steel chassis and superstructure clad with aluminium panels designed by DHMC’s Gerry Coker and hand-beaten by Tickford in Newport Pagnell. Beneath the skin, the front suspension employed coil springs and wishbones, while the axle was carried on semi-elliptic leaf springs, and there were Armstrong lever-arm dampers all round. Burman cam- and-peg steering, 10in (254mm) Girling drum brakes, and centre-lock wire wheels rounded off the running gear, while the Austin A90 transmission was equipped with Laycock de Normanville overdrive. It was an exciting concoction, and was far from a static mock-up – the prototype had been timed shortly before the show at 111.7mph (179.8km/h) on a stretch of motorway just outside Jabbeke in Belgium.

The 100 was the first model to wear the Austin-Healey badge. It would become a huge success for DHMC.

Although other British sports cars making their debut at the 1952 show included the Frazer-Nash Targa Florio (which also employed the A90 engine) and Triumph TS20 (the genesis of the highly successful TR2), in its Earls Court summary Motor Sport concluded that the Healey was ‘Sports Car of the Year’. The writers were absolutely correct in their assertion, and not alone in their appreciation of the Hundred: so, too, was the de facto boss of BMC.

Following the advice of his former rally partner Tommy Wisdom, Donald Healey had approached Austin chairman Leonard Lord on 27 November 1951 to secure a supply of A90 power units for his embryonic project. Lord had enthusiastically welcomed the overture – not only would he be happy to provide engines, but also gearboxes, axles and other components as required. Such enthusiasm may have been influenced by a surplus of A90 parts after the Atlantic had failed to catch on, but it gave Healey what he needed. Eleven months later, keen to see how his hardware was being used, Lord was among the first visitors to Earls Court to cast an eye over the Hundred; like the journalists at Motor Sport, he was very impressed.

Unveiled in 1955, the MGA had a maximum speed of very nearly 100mph (160km/h).

In manufacturing terms, of course, the DHMC factory in Warwick was not geared up to turn out cars in the manner of a conglomerate such as BMC – Gerry Coker and Geoffrey Healey recalled in later life that somewhere between five and twenty-five cars a week had been envisaged. Upon seeing the Healey, however, Lord was sufficiently stirred to propose a deal that was difficult to refuse: the corporation would put the Hundred into production, rebadging it as the Austin-Healey 100 and marketing it worldwide through the BMC dealership network. DHMC, meanwhile, would be retained on a consultancy basis to assist with development as well as a busy BMC-sponsored motor-sport programme, and would receive a £5 royalty on each car sold. Donald Healey readily accepted, and after being prepared for production by BMC – changes included steel panels in place of aluminium – the 100 went on sale in early 1953.

DONALD HEALEY

Born on 3 July 1898 in Perranporth on the north coast of Cornwall, Donald Mitchell Healey was the elder of the two sons of shopkeepers Emmie and John Frederick Healey.

Having always shown an interest in engineering, upon leaving school Healey initially attended Newquay College, but in 1914 he moved to Kingston-upon-Thames to embark on an apprenticeship with aircraft manufacturer Sopwith. He received his pilot’s wings on 20 June 1916, having enlisted for the Royal Flying Corps earlier that year; however, within weeks he crashed his BE2C biplane as a result of engine failure. He later flew anti-Zeppelin patrols in Lincolnshire, and served as an instructor before being sent to France but was invalided out of the RFC in November 1917, having been brought down by British artillery during a night bombing raid.

In 1919, Healey returned to Perranporth and began a correspondence course in automotive engineering; the following year he opened Red House Garage. On 21 October 1921 he married local girl Ivy Maude James, and the couple had three sons: Geoffrey, Brian (‘Bic’) and John.

During the 1920s Healey enjoyed considerable motor-sport success, and in 1929 entered a Triumph Super Seven on the Monte-Carlo Rally. Although he was disqualified on that first attempt, seventh in 1930 brought him to the attention of Invicta-founder Noel Macklin – in 1931 the Cornishman took one of Macklin’s 4½-litre S-types to victory, following it up with second in 1932.

In 1933, following a brief spell at Coventry-based Riley, Healey joined Triumph, first as experimental manager and later as technical director. During his time there, he masterminded the supercharged Dolomite straight-eight (a 140bhp homage to the Alfa Romeo 8C 2300), as well as competing as a works rally driver. After taking a modified Gloria to third on the 1934 ‘Monte’, Healey was looking for a win in 1935 – but his hopes were cut short when his Dolomite smashed into a train on a foggy level crossing in Denmark.

Triumph’s bankruptcy in 1939 led Healey to Humber in 1940, where in his spare time (aside from duties in the RAF Volunteer Reserve) he began imagining a high-performance car in the mould of the BMW 328. By 1946 the idea of badging the machine as a Triumph had foundered, so, abetted by Italian chassis specialist Achille ‘Sammy’ Sampietro and body engineer Ben Bowden (both of whom he had met at Humber), he formed the Donald Healey Motor Company and was soon building cars in an RAF hangar in Warwick. These would be followed by a tie-up with Wisconsin-based Nash in 1951, while in 1952 the Austin-Healey marque was born.

Healey piloted his eponymous cars on numerous events, including on the Alpine Rally in 1948–49, as well as six drives on the Mille Miglia from 1948 to 1955, when he was regularly partnered by his eldest son. He also established a series of speed records driving Austin-Healeys at Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, beginning with 142.64mph (229.56km/h) in a standard-looking 100 in September 1953. In the following year he raised that to 192.74mph (310.19km/h) with a befinned streamliner that looked more Gerry Anderson than Gerry Coker. Then in 1956 the fifty-eight-year-old became one of the handful of men to have topped 200mph (322km/h) on land, taking a 292bhp supercharged 100-Six to 203.11mph (326.87km/h).

Donald Healey (right) with Carroll Shelby (left) and Roy Jackson-Moore (centre) pictured at Bonneville Salt Flats in August ’56.

The Jensen-Healey featured the 16-valve 1973cc Lotus 907 twin-cam engine but didn’t catch on.

The 1956 record marked the end of Healey’s driving career, but the short stout extrovert continued to enjoy an active life. Aside from cars he also manufactured speedboats under the Healey Marine banner, while in 1961 he purchased the 27-acre Trebah estate in Cornwall, where he lived until 1971. There he built commercial greenhouses and air-sea-rescue inflatables, as well as dabbling with steam power and wind turbines.

Following the demise of Austin-Healey, the Cornishman turned his attention towards West Bromwich-based Jensen, becoming company chairman in 1970 and playing a leading role in the ill-fated Jensen-Healey. Launched at the 1972 Geneva Salon, the Lotus-engined sports car was a spiritual successor to the Austin-Healey 3000, but failed to survive Jensen’s mid-1970s financial collapse.

In 1973, Healey’s contribution to British exports was rewarded with a CBE and, although the following year he sold DHMC (which by then was reduced to a car dealership), he retained an active interest in Healey Automotive Consultants, which had been set up in 1955 as an engineering division. In later years HAC was involved in numerous projects, including a Saab sports car and a tuned 1596cc Ford Fiesta Mk I for the US market, although both were stillborn.

Donald Healey died in Truro on 15 January 1988, at the age of eighty-nine.

THE DONALD HEALEY MOTOR COMPANY

During the 1940s, Donald Healey had begun toying with the idea of a high-performance car inspired by the six-cylinder BMW 328, hoping that the design might be adopted for manufacture by Triumph. The Coventry firm was unconvinced, however, so with the help of former Humber colleagues Sammy Sampietro and Ben Bowden, the Cornish engineer decided to build it himself – thus founding the Donald Healey Motor Company.

In spite of a shortage of materials in post-war Britain, a prototype was built in a corner of the Benford concrete-mixer factory in Warwick, although the nascent DHMC soon acquired its own premises at The Cape. Unveiled in 1946, the first Healey was powered by the twin-high-camshaft 2443cc Riley ‘Big Four’; it was offered with an open four-seater body by Westland Engineering, or saloon coachwork by Samuel Elliott & Sons. The latter became the fastest production car of its day when (in spite of running on low-grade ‘pool’ petrol) it was timed at a phenomenal 110.65mph (178.07km/h) on the Jabbeke motorway in Belgium.

The car spawned a number of variants, including the Tickford, Abbott, Duncan and Sportsmobile, as well as the spartan Silverstone roadster. The marque would prove its mettle in international motor sport, but Healeys were expensive, and Jaguar’s astonishingly fast and affordable XK120 made them slow sellers – a meagre 491 had been built by the time production ended in 1954. Fortunately for DHMC, a chance encounter aboard the Queen Elizabeth in 1949 would lead to a successful new Anglo-American venture.

Travelling to the United States in the hope of securing a supply of Cadillac V8s, one of Healey’s fellow passengers was Nash-Kelvinator president George Mason. The two were soon talking cars and, although the Cadillac deal came to nothing, Mason would sponsor a 3.8-litre roadster that merged Nash Ambassador mechanicals and a Healey chassis. Marketed through the Wisconsin firm’s American dealer network but designed and built in Warwick, the six-cylinder Nash-Healey entered production in December 1950. Like its Riley-powered forebears, it was soon being raced, Leslie Johnson and Tommy Wisdom crowning its career with third overall at Le Mans in 1952 (beaten only by the works Mercedes 300SLs).

Early Nash-Healeys were clothed in aluminium by Panelcraft Sheet Metal of Woodgate in Birmingham, but a second series with steel bodywork by Pinin Farina followed from 1952, making for an exceptionally long assembly line – running gear was sent from Wisconsin to England, with rolling chassis then dispatched to Turin and finished cars shipped to America. The deal certainly kept DHMC afloat, but Healey recognized the need for a machine to replace the Riley-engined series, so in 1951 embarked on a project employing cheaper Austin mechanicals. The result was the Healey Hundred, which led to a hugely successful collaboration with BMC (while in a curious twist, Nash also teamed up with Longbridge for the Metropolitan of 1954 to 1961).

DHMC built only 222 examples of its Riley-engined Tickford saloon.

The second version of the Nash-Healey featured coachwork by Farina of Turin.

During the Austin-Healey era, DHMC wound down its manufacturing: the Nash-Healey was axed in 1954 after a total of 506 cars, plus twenty-five Alvis-engined G-types from 1951 to 1953. However, it ran a competition programme on behalf of BMC, as well as the Healey Automotive Consultants engineering subsidiary, and a dealer franchise managed by Bic Healey. In 1963 the company relocated from The Cape to a former cinema at Coten End in Warwick – the site was opened by Alec Issigonis on Donald Healey’s sixty-fifth birthday – but the cost of maintaining an additional showroom and tuning operation in Mayfair meant that those eventually closed.

The EX219 ‘Sprite’ takes centre stage outside DHMC’s Coten End premises in Warwick.

After the Austin-Healey marque was culled, DHMC dropped its BL franchise in favour of Fiat, and on 14 December 1974 the family sold the business (although Donald and Geoffrey retained ownership of Healey Automotive Consultants).

LEONARD LORD

The youngest son of William and Emma Lord (née Swain), Leonard Percy Lord was born on 15 November 1896. Having studied at Bablake School in Coventry, at the age of sixteen he began an engineering apprenticeship, and by 1922 had joined the British subsidiary of Paris-based automobile manufacturer Hotchkiss.

The Hotchkiss concern on Gosford Street in Coventry was bought by Morris Motors in 1923, and before the end of the decade Lord had been singled out by his new employer to restructure Wolseley, which had been purchased by William Morris as a private investment in 1927. Blunt, down to earth and bespectacled, ‘Spiky’ (as Lord became known on the shop floor) was a talented production manager and proved instrumental in reviving the flagging Birmingham-based marque.

The brain behind BMC: Sir Leonard Lord.

As a result of his efforts at Wolseley, in 1932 Lord was appointed general manager of Morris’ Cowley plant, later rising to become managing director of Morris Motors (which in 1934 would be renamed the Nuffield Organization, echoing William Morris’ elevation to the peerage). Second only to the company founder, Lord frequently endured conflict with his autocratic boss, and a dispute in 1936 led to his resignation and early retirement. Two years later, however, he joined Morris’ arch rival Austin, and vowed to beat his former employer at his own game.

Lord rapidly ascended the ranks and, in November 1945, four and a half years after the death of Sir Herbert Austin, was named company chairman. Aggressive modernization and expansion of the business – including setting up factories in Argentina, Australia, Canada, Mexico and South Africa – meant that by the time of its 1952 merger with Nuffield, Austin was the dominant force, and Lord would play a key role in running BMC. In 1954 (the same year that he was awarded the KBE), he replaced Lord Nuffield as chairman of the conglomerate, and retained the role for seven years; during this time the corporation’s annual sales climbed to more than 500,000 vehicles.

In 1961 Lord ceded the chairmanship to his protégé George Harriman (whom he had first met at Morris in the 1920s), and accepted the honorary position of vice president. He then shifted his attention to rearing Hereford bulls. On 26 March 1962 he was made Baron Lambury (thus avoiding the title ‘Lord Lord’!); following the death of Lord Nuffield in August 1963, he took over the symbolic mantle of BMC president. He died aged 70 on 13 September 1967, just as the business empire he had so vigorously worked to create was preparing to merge with Leyland.

A SMALLER CAR FOR A GROWING MARKET

Over the next decade and a half, the Austin-Healey would gradually evolve into a less spartan, but also more powerful and faster machine. The 100-Six of 1956 brought about a mild facelift and a 2in (50mm) longer wheelbase, as well as BMC’s 102bhp 2639cc six-cylinder in place of the 90bhp 2660cc ‘four’. Three years later, front disc brakes and a 2912cc ‘six’ marked the arrival of the 3000, which by its final Mk III guise would develop a healthy 148bhp. Collectively known today as the Big Healey, the 100, 100-Six and 3000 were a phenomenal commercial success – some 72,000 were built – and would earn an outstanding reputation in rallying, where, in spite of limited ground clearance, their rugged construction and considerable torque made them very serious contenders.

At the time of its launch, the 100 had provided BMC with a more sophisticated stablemate to the popular but antiquated MG TD, and just as the Big Healey would move upmarket, so MG followed suit. In October 1953 the sleeker TF took over the baton for Abingdon, while in 1954 that car’s 1250cc ‘four’ would be superseded by a 1466cc unit developing 63bhp. Just over a year later, in September 1955, an entirely new roadster was unveiled at the Frankfurt show in West Germany: the MGA.

Fitted with a 68bhp 1489cc twin-carburettor version of the mid-size BMC B-series engine (boosted soon after launch to 72bhp), the latest offering from Abingdon was a far cry from the pre-war Midgets that had established the marque. Clothed in curvaceous all-enveloping bodywork, the MGA was longer and heavier than its predecessors, as well as significantly faster. When The Motor sampled an early example in 1955, it recorded a 0–60mph time of 16sec and a top speed of 97.8mph (157.4km/h) – not that far off the Austin-Healey 100’s figures. At £844 including purchase tax, the MG was also creeping towards the Healey in price. A niche was opening up at the bottom of the BMC range for an inexpensive new sports car.

CHAPTER TWO

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Not everyone, even with memories of their Meccano days still clear, wants to build a sports car. For this reason I think a return on the part of our manufacturers to under-1100cc sports cars is overdue. They would represent attractive vehicles both for home consumption and export.

Bill Boddy, Motor Sport, July 1954

The Sprite would not see the light of day until 1958, but as far back as 1953 the Longbridge engineers had attempted to address the niche for a simple roadster echoing the pre-war Austin Seven. Based on the running gear of the A30, the prototype 7hp Sports Tourer (or A30 Sports) was a compact open-top two-seater with a tubular-steel space frame and doorless glassfibre bodywork – a now prosaic material, but one which in the 1950s was at the forefront of automotive composite technology.

Based on clay models by Argentinian-born Ricardo ‘Dick’ Burzi, who had been Austin’s in-house stylist since leaving Lancia in 1929, the aesthetics of the A30 Sports are best described as mitigated. From behind – the most convincing angle – the pint-sized machine was quite pretty (and bore a striking resemblance to the contemporary Sunbeam Alpine), while in profile the low-cut sides lent it the rakish flavour of the Jowett Jupiter or Triumph TR2. From the front, however, the tall windscreen, oval grille and large cowled headlights were more naïve, with the unfortunate look of a bottom-feeding fish.