When Shan Tung, the

long-cued Chinaman from Vancouver, started up the Frazer River in

the old days when the Telegraph Trail and the headwaters of the

Peace were the Meccas of half the gold-hunting population of

British Columbia, he did not foresee tragedy ahead of him. He was a

clever man, was Shan Tung, a cha-sukeed, a very devil in the

collecting of gold, and far-seeing. But he could not look forty

years into the future, and when Shan Tung set off into the north,

that winter, he was in reality touching fire to the end of a fuse

that was to burn through four decades before the explosion

came.

With Shan Tung went Tao, a Great

Dane. The Chinaman had picked him up somewhere on the coast and had

trained him as one trains a horse. Tao was the biggest dog ever

seen about the Height of Land, the most powerful, and at times the

most terrible. Of two things Shan Tung was enormously proud in his

silent and mysterious oriental way—of Tao, the dog, and of his

long, shining cue which fell to the crook of his knees when he let

it down. It had been the longest cue in Vancouver, and therefore it

was the longest cue in British Columbia. The cue and the dog formed

the combination which set the forty-year fuse of romance and

tragedy burning. Shan Tung started for the El Dorados early in the

winter, and Tao alone pulled his sledge and outfit. It was no more

than an ordinary task for the monstrous Great Dane, and Shan Tung

subserviently but with hidden triumph passed outfit after outfit

exhausted by the way. He had reached Copper Creek Camp, which was

boiling and frothing with the excitement of gold-maddened men, and

was congratulating himself that he would soon be at the camps west

of the Peace, when the thing happened. A drunken Irishman, filled

with a grim and unfortunate sense of humor, spotted Shan Tung's

wonderful cue and coveted it. Wherefore there followed a bit of

excitement in which Shan Tung passed into his empyrean home with a

bullet through his heart, and the drunken Irishman was strung up

for his misdeed fifteen minutes later. Tao, the Great Dane, was

taken by the leader of the men who pulled on the rope. Tao's new

master was a "drifter," and as he drifted, his face was always set

to the north, until at last a new humor struck him and he turned

eastward to the Mackenzie. As the seasons passed, Tao found mates

along the way and left a string of his progeny behind him, and he

had new masters, one after another, until he was grown old and his

muzzle was turning gray. And never did one of these masters turn

south with him. Always it was north, north with the white man

first, north with the Cree, and then wit h the Chippewayan, until

in the end the dog born in a Vancouver kennel died in an Eskimo

igloo on the Great Bear. But the breed of the Great Dane lived on.

Here and there, as the years passed, one would find among the

Eskimo trace-dogs, a grizzled-haired, powerful-jawed giant that was

alien to the arctic stock, and in these occasional aliens ran the

blood of Tao, the Dane.

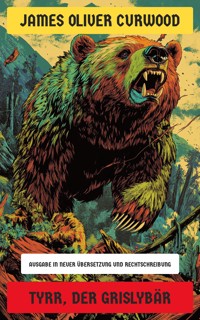

Forty years, more or less, after

Shan Tung lost his life and his cue at Copper Creek Camp, there was

born on a firth of Coronation Gulf a dog who was named Wapi, which

means "the Walrus." Wapi, at full growth, was a throwback of more

than forty dog generations. He was nearly as large as his

forefather, Tao. His fangs were an inch in length, his great jaws

could crack the thigh-bone of a caribou, and from the beginning the

hands of men and the fangs of beasts were against him. Almost from

the day of his birth until this winter of his fourth year, life for

Wapi had been an unceasing fight for existence. He was

maya-tisew—bad with the badness of a devil. His reputation had gone

from master to master and from igloo to igloo; women and children

were afraid of him, and men always spoke to him with the club or

the lash in their hands. He was hated and feared, and yet because

he could run down a barren-land caribou and kill it within a mile,

and would hold a big white bear at bay until the hunters came, he

was not sacrificed to this hate and fear. A hundred whips and clubs

and a hundred pairs of hands were against him between Cape Perry

and the crown of Franklin Bay—and the fangs of twice as many

dogs.

The dogs were responsible.

Quick-tempered, clannish with the savage brotherhood of the wolves,

treacherous, jealous of leadership, and with the older instincts of

the dog dead within them, their merciless feud with what they

regarded as an interloper of another breed put the devil heart in

Wapi. In all the gray and desolate sweep of his world he had no

friend. The heritage of Tao, his forefather, had fallen upon him,

and he was an alien in a land of strangers. As the dogs and the men

and women and children hated him, so he hated them. He hated the

sight and smell of the round-faced, blear-eyed creatures who were

his master, yet he obeyed them, sullenly, watchfully, with his lips

wrinkled warningly over fangs which had twice torn out the life of

white bears. Twenty times he had killed other dogs. He had fought

them singly, and in pairs, and in packs. His giant body bore the

scars of a hundred wounds. He had been clubbed until a part of his

body was deformed and he traveled with a limp. He kept to himself

even in the mating season. And all this because Wapi, the Walrus,

forty years removed from the Great Dane of Vancouver, was a white

man's dog.

Stirring restlessly within him,

sometimes coming to him in dreams and sometimes in a great and

unfulfilled yearning, Wapi felt vaguely the strange call of his

forefathers. It was impossible for him to understand. It was

impossible for him to know what it meant. And yet he did know that

somewhere there was something for which he was seeking and which he

never found. The desire and the questing came to him most

compellingly in the long winter filled with its eternal starlight,

when the maddening yap, yap, yap of the little white foxes, the

barking of the dogs, and the Eskimo chatter oppressed him like the

voices of haunting ghosts. In these long months, filled with the

horror of the arctic night, the spirit of Tao whispered within him

that somewhere there was light and sun, that somewhere there was

warmth and flowers, and running streams, and voices he could

understand, and things he could love. And then Wapi would whine,

and perhaps the whine would bring him the blow of a club, or the

lash of a whip, or an Eskimo threat, or the menace of an Eskimo

dog's snarl. Of the latter Wapi was unafraid. With a snap of his

jaws, he could break the back of any other dog on Franklin

Bay.

Such was Wapi, the Walrus, when

for two sacks of flour, some tobacco, and a bale of cloth he became

the property of Blake, the uta-wawe-yinew, the trader in seals,

whalebone—and women. On this day Wapi's soul took its flight back

through the space of forty years. For Blake was white, which is to

say that at one time or another he had been white. His skin and his

appearance did not betray how black he had turned inside and Wapi's

brute soul cried out to him, telling him how he had waited and

watched for this master he knew would come, how he would fight for

him, how he wanted to lie down and put his great head on the white

man's feet in token of his fealty. But Wapi's bloodshot eyes and

battle-scarred face failed to reveal what was in him, and

Blake—following the instructions of those who should know—ruled him

from the beginning with a club that was more brutal than the club

of the Eskimo.

For three months Wapi had been

the property of Blake, and it was now the dead of a long and

sunless arctic night. Blake's cabin, built of ship timber and

veneered with blocks of ice, was built in the face of a deep pit

that sheltered it from wind and storm. To this cabin came the

Nanatalmutes from the east, and the Kogmollocks from the west,

bartering their furs and whalebone and seal-oil for the things

Blake gave in exchange, and adding women to their wares whenever

Blake announced a demand. The demand had been excellent this

winter. Over in Darnley Bay, thirty miles across the headland, was

the whaler Harpoon frozen up for the winter with a crew of thirty

men, and straight out from the face of his igloo cabin, less than a

mile away, was the Flying Moon with a crew of twenty more. It was

Blake's business to wait and watch like a hawk for such

opportunities as there, and tonight—his watch pointed to the hour

of twelve, midnight—he was sitting in the light of a sputtering

seal-oil lamp adding up figures which told him that his winter,

only half gone, had already been an enormously profitable

one.

"If the Mounted Police over at

Herschel only knew," he chuckled. "Uppy, if they did, they'd have

an outfit after us in twenty-four hours."

Oopi, his Eskimo right-hand man,

had learned to understand English, and he nodded, his moon-face

split by a wide and enigmatic grin. In his way, "Uppy" was as

clever as Shan Tung had been in his.

And Blake added, "We've sold

every fur and every pound of bone and oil, and we've forty Upisk

wives to our credit at fifty dollars apiece."

Uppy's grin became larger, and

his throat was filled with an exultant rattle. In the matter of the

Upisk wives he knew that he stood ace-high.

"Never," said Blake, "has our

wife-by-the-month business been so good. If it wasn't for Captain

Rydal and his love-affair, we'd take a vacation and go

hunting."

He turned, facing the Eskimo, and

the yellow flame of the lamp lit up his face. It was the face of a

remarkable man. A black beard concealed much of its cruelty and its

cunning, a beard as carefully Van-dycked as though Blake sat in a

professional chair two thousand miles south, but the beard could

not hide the almost inhuman hardness of the eyes. There was a

glittering light in them as he looked at the Eskimo. "Did you see

her today, Uppy? Of course you did. My Gawd, if a woman could ever

tempt me, she could! And Rydal is going to have her. Unless I miss

my guess, there's going to be money in it for us—a lot of it. The

funny part of it is, Rydal's got to get rid of her husband. And

how's he going to do it, Uppy? Eh? Answer me that. How's he going

to do it?"

In a hole he had dug for himself

in the drifted snow under a huge scarp of ice a hundred yards from

the igloo cabin lay Wapi. His bed was red with the stain of blood,

and a trail of blood led from the cabin to the place where he had

hidden himself. Not many hours ago, when by God's sun it should

have been day, he had turned at last on a teasing, snarling,

back-biting little kiskanuk of a dog and had killed it. And Blake

and Uppy had beaten him until he was almost dead.

It was not of the beating that

Wapi was thinking as he lay in his wallow. He was thinking of the

fur-clad figure that had come between Blake's club and his body, of

the moment when for the first time in his life he had seen the face

of a white woman. She had stopped Blake's club. He had heard her

voice. She had bent over him, and she would have put her hand on

him if his master had not dragged her back with a cry of warning.

She had gone into the cabin then, and he had dragged himself

away.

Since then a new and thrilling

flame had burned in him. For a time his senses had been dazed by

his punishment, but now every instinct in him was like a living

wire. Slowly he pulled himself from his retreat and sat down on his

haunches. His gray muzzle was pointed to the sky. The same stars

were there, burning in cold, white points of flame as they had

burned week after week in the maddening monotony of the long nights

near the pole. They were like a million pitiless eyes, never

blinking, always watching, things of life and fire, and yet dead.

And at those eyes, the little white foxes yapped so incessantly

that the sound of it drove men mad. They were yapping now. They

were never still. And with their yapping came the droning, hissing

monotone of the aurora, like the song of a vast piece of mechanism

in the still farther north. Toward this Wapi turned his bruised and

beaten head. Out there, just beyond the ghostly pale of vision, was

the ship. Fifty times he had slunk out and around it, cautiously as

the foxes themselves. He had caught its smells and its sounds; he

had come near enough to hear the voices of men, and those voices

were like the voice of Blake, his master. Therefore, he had never

gone nearer.

There was a change in him now.

His big pads fell noiselessly as he slunk back to the cabin and

sniffed for a scent in the snow. He found it. It was the trail of

the white woman. His blood tingled again, as it had tingled when

her face bent over him and her hand reached out, and in his soul

there rose up the ghost of Tao to whip him on. He followed the

woman's footprints slowly, stopping now and then to listen, and

each moment the spirit in him grew more insistent, and he whined up

at the stars. At last he saw the ship, a wraithlike thing in its

piled-up bed of ice, and he stopped. This was his dead-line. He had

never gone nearer. But tonight—if any one period could be called

night—he went on.

It was the hour of sleep, and

there was no sound aboard. The foxes, never tiring of their

infuriating sport, were yapping at the ship. They barked faster and

louder when they caught the scent of Wapi, and as he approached,

they drifted farther away. The scent of the woman's trail led up

the wide bridge of ice, and Wapi followed this as he would have

followed a road, until he found himself all at once on the deck of

the Flying Moon. For a space he was startled. His long fangs bared

themselves at the shadows cast by the stars. Then he saw ahead of

him a narrow ribbon of yellow light. Toward this Wapi sniffed out,

step by step, the footprints of the woman. When he stopped again,

his muzzle was at the narrow crack through which came the glimmer

of light.

It was the door of a deck-house

veneered like an igloo with snow and ice to protect it from cold

and wind. It was, perhaps, half an inch ajar, and through that

aperture Wapi drank the warm, sweet perfume of the woman. With it

he caught also the smell of a man. But in him the woman scent

submerged all else. Overwhelmed by it, he stood trembling, not

daring to move, every inch of him thrilled by a vast and mysterious

yearning. He was no longer Wapi, the Walrus; Wapi, the Killer. Tao

was there. And it may be that the spirit of Shan Tung was there.

For after forty years the change had come, and Wapi, as he stood at

the woman's door, was just dog,—a white man's dog—again the dog of

the Vancouver kennel—the dog of a white man's world.

He thrust open the door with his

nose. He slunk in, so silently that he was not heard. The cabin was

lighted. In a bed lay a white-faced, hollow-cheeked man—awake. On a

low stool at his side sat a woman. The light of the lamp hanging

from above warmed with gold fires the thick and radiant mass of her

hair. She was leaning over the sick man. One slim, white hand was

stroking his face gently, and she was speaking to him in a voice so

sweet and soft that it stirred like wonderful music in Wapi's

warped and beaten soul. And then, with a great sigh, he flopped

down, an abject slave, on the edge of her dress.

With a startled cry the woman

turned. For a moment she stared at the great beast wide-eyed, then

there came slowly into her face recognition and understanding.

"Why, it's the dog Blake whipped so terribly," she gasped. "Peter,

it's—it's Wapi!" For the first time Wapi felt the caress of a

woman's hand, soft, gentle, pitying, and out of him there came a

wimpering sound that was almost a sob.

"It's the dog—he whipped," she

repeated, and, then, if Wapi could have understood, he would have

noted the tense pallor of her lovely face and the look of a great

fear that was away back in the staring blue depths of her

eyes.

From his pillow Peter Keith had

seen the look of fear and the paleness of her cheeks, but he was a

long way from guessing the truth. Yet he thought he knew. For

days—yes, for weeks—there had been that growing fear in her eyes.

He had seen her mighty fight to hide it from him. And he thought he

understood.

"I know it has been a terrible

winter for you, dear," he had said to her many times. "But you

mustn't worry so much about me. I'll be on my feet again—soon." He

had always emphasized that. "I'll be on my feet again soon!"

Once, in the breaking terror of

her heart, she had almost told him the truth. Afterward she had

thanked God for giving her the strength to keep it back. It was

day—for they spoke in terms of day and night—when Rydal, half

drunk, had dragged her into his cabin, and she had fought him until

her hair was down about her in tangled confusion—and she had told

Peter that it was the wind. After that, instead of evading him, she

had played Rydal with her wits, while praying to God for help. It

was impossible to tell Peter. He had aged steadily and terribly in

the last two weeks. His eyes were sunken into deep pits. His blond

hair was turning gray over the temples. His cheeks were hollowed,

and there was a different sort of luster in his eyes. He looked

fifty instead of thirty-five. Her heart bled in its agony. She

loved Peter with a wonderful love.

The truth! If she told him that!

She could see Peter rising up out of his bed like a ghost. It would

kill him. If he could have seen Rydal—only an hour before—stopping

her out on the deck, taking her in his arms, and kissing her until

his drunken breath and his beard sickened her! And if he could have

heard what Rydal had said! She shuddered. And suddenly she dropped

down on her knees beside Wapi and took his great head in her arms,

unafraid of him—and glad that he had come.

Then she turned to Peter. "I'm

going ashore to see Blake again—now," she said. "Wapi will go with

me, and I won't be afraid. I insist that I am right, so please

don't object any more, Peter dear."

She bent over and kissed him, and

then in spite of his protest, put on her fur coat and hood, and

stood for a moment smiling down at him. The fear was gone out of

her eyes now. It was impossible for him not to smile at her

loveliness. He had always been proud of that. He reached up a thin

hand and plucked tenderly at the shining little tendrils of gold

that crept out from under her hood.

"I wish you wouldn't, dear," he

pleaded.

How pathetically white, and thin,

and weak he was! She kissed him again and turned quickly to hide

the mist in her eyes. At the door she blew him a kiss from the tip

of her big fur mitten, and as she went out she heard him say in the

thin, strange voice that was so unlike the old Peter:

"Don't be long, Dolores."

She stood silently for a few

moments to make sure that no one would see her. Then she moved

swiftly to the ice bridge and out into the star-lighted ghostliness

of the night. Wapi followed close behind her, and dropping a hand

to her side she called softly to him. In an instant Wapi's muzzle

was against her mitten, and his great body quivered with joy at her

direct speech to him. She saw the response in his red eyes and

stopped to stroke him with both mittened hands, and over and over

again she spoke his name. "Wapi—Wapi—Wapi." He whined. She could

feel him under her touch as if alive with an electrical force. Her

eyes shone. In the white starlight there was a new emotion in her

face. She had found a friend, the one friend she and Peter had, and

it made her braver.

At no time had she actually been

afraid—for herself. It was for Peter. And she was not afraid now.

Her cheeks flushed with exertion and her breath came quickly as she

neared Blake's cabin. Twice she had made excuses to go ashore—just

because she was curious, she had said—and she believed that she had

measured up Blake pretty well. It was a case in which her woman's

intuition had failed her miserably. She was amazed that such a man

had marooned himself voluntarily on the arctic coast. She did not,

of course, understand his business—entirely. She thought him simply

a trader. And he was unlike any man aboard ship. By his carefully

clipped beard, his calm, cold manner of speech, and the unusual

correctness with which he used his words she was convinced that at

some time or another he had been part of what she mentally thought

of as "an entirely different environment."

She was right. There was a time

when London and New York would have given much to lay their hands

on the man who now called himself Blake.

Dolores, excited by the

conviction that Blake would help her when he heard her story, still

did not lose her caution. Rydal had given her another twenty-four

hours, and that was all. In those twenty-four hours she must fight

out their salvation, her own and Peter's. If Blake should

fail—

Fifty paces from his cabin she

stopped, slipped the big fur mitten from her right hand and

unbuttoned her coat so that she could quickly and easily reach an

inside pocket in which was Peter's revolver. She smiled just a bit

grimly, as her fingers touched the cold steel. It was to be her

last resort. And she was thinking in that flash of the days "back

home" when she was counted the best revolver shot at the Piping

Rock. She could beat Peter, and Peter was good. Her fingers twined

a bit fondly about the pearl-handled thing in her pocket. The last

resort—and from the first it had given her courage to keep the

truth from Peter!

She knocked at the heavy door of

the igloo cabin. Blake was still up, and when he opened it, he

stared at her in wide-eyed amazement. Wapi hung outside when

Dolores entered, and the door closed. "I know you think it strange

for me to come at this hour," she apologized, "but in this terrible

gloom I've lost all count of hours. They have no significance for

me any more. And I wanted to see you—alone."

She emphasized the word. And as

she spoke, she loosened her coat and threw back her hood, so that

the glow of the lamp lit up the ruffled mass of gold the hood had

covered. She sat down without waiting for an invitation, and Blake

sat down opposite her with a narrow table between them. Her face

was flushed with cold and wind as she looked at him. Her eyes were

blue with the blue of a steady flame, and they met his own

squarely. She was not nervous. Nor was she afraid.

"Perhaps you can guess—why I have

come?" she asked.

He was appraising her almost

startling beauty with the lamp glow flooding down on her. For a

moment he hesitated; then he nodded, looking at her steadily. "Yes,

I think I know," he said quietly. "It's Captain Rydal. In fact, I'm

quite positive. It's an unusual situation, you know. Have I guessed

correctly?"

She nodded, drawing in her breath

quickly and leaning a little toward him, wondering how much he knew

and how he had come by it.

"A very unusual situation," he

repeated. "There's nothing in the world that makes beasts out of

men—most men—more quickly than an arctic night, Mrs. Keith. And

they're all beasts out there—now—all except your husband, and he is

contented because he possesses the one white woman aboard ship.

It's putting it brutally plain, but it's the truth, isn't it? For

the time being they're beasts, every man of the twenty, and

you—pardon me!—are very beautiful. Rydal wants you, and the fact

that your husband is dying—"

"He is not dying," she

interrupted him fiercely. "He shall not die! If he did—"

"Do you love him?" There was no

insult in Blake's quiet voice. He asked the question as if much

depended on the answer, as if he must assure himself of that

fact.

"Love him—my Peter? Yes!"

She leaned forward eagerly,

gripping her hands in front of him on the table. She spoke swiftly,

as if she must convince him before he asked her another question.

Blake's eyes did not change. They had not changed for an instant.

They were hard, and cold, and searching, unwarmed by her beauty, by

the luster of her shining hair, by the touch of her breath as it

came to him over the table.

"I have gone everywhere with

him—everywhere," she began. "Peter writes books, you know, and we

have gone into all sorts of places. We love it—both of us—this

adventuring. We have been all through the country down there," she

swept a hand to the south, "on dog sledges, in canoes, with

snowshoes, and pack-trains. Then we hit on the idea of coming north

on a whaler. You know, of course, Captain Rydal planned to return

this autumn. The crew was rough, but we expected that. We expected

to put up with a lot. But even before the ice shut us in, before

this terrible night came, Rydal insulted me. I didn't dare tell

Peter. I thought I could handle Rydal, that I could keep him in his

place, and I knew that if I told Peter, he would kill the beast.

And then the ice—and this night—" She choked.

Blake's eyes, gimleting to her

soul, were shot with a sudden fire as he, too, leaned a little over

the table. But his voice was unemotional as rock. It merely stated

a fact. "That's why Captain Rydal allowed himself to be frozen in,"

he said. "He had plenty of time to get into the open channels, Mrs.

Keith. But he wanted you. And to get you he knew he would have to

lay over. And if he laid over, he knew that he would get you, for

many things may happen in an arctic night. It shows the depth of

the man's feelings, doesn't it? He is sacrificing a great deal to

possess you, losing a great deal of time, and money, and all that.

And when your husband dies—"

Her clenched little fist struck

the table. "He won't die, I tell you! Why do you say that?"

"Because—Rydal says he is going

to die."

"Rydal—lies. Peter had a fall,

and it hurt his spine so that his legs are paralyzed. But I know

what it is. If he could get away from that ship and could have a

doctor, he would be well again in two or three months."

"But Rydal says he is going to

die."

There was no mistaking the

significance of Blake's words this time. Her eyes filled with

sudden horror. Then they flashed with the blue fire again. "So—he

has told you? Well, he told me the same thing today. He didn't

intend to, of course. But he was half mad, and he had been

drinking. He has given me twenty-four hours."

"In which to—surrender?"

There was no need to reply.

For the first time Blake smiled.

There was something in that smile that made her flesh creep.

"Twenty-four hours is a short time," he said, "and in this matter,

Mrs. Keith, I think that you will find Captain Rydal a man of his

word. No need to ask you why you don't appeal to the crew! Useless!

But you have hope that I can help you? Is that it?"

Her heart throbbed. "That is why

I have come to you, Mr. Blake. You told me today that Fort

Confidence is only a hundred and fifty miles away and that a

Northwest Mounted Police garrison is there this winter—with a

doctor. Will you help me?"

"A hundred and fifty miles, in

this country, at this time of the year, is a long distance, Mrs.

Keith," reflected Blake, looking into her eyes with a steadiness

that at any other time would have been embarrassing. "It means the

McFarlane, the Lacs Delesse, and the Arctic Barren. For a hundred

miles there isn't a stick of timber. If a storm came—no man or dog

could live. It is different from the coast. Here there is shelter

everywhere." He spoke slowly, and he was thinking swiftly. "It

would take five days at thirty miles a day. And the chances are

that your husband would not stand it. One hundred and twenty hours

at fifty degrees below zero, and no fire until the fourth day. He

would die."

"It would be better—for if we

stay—" she stopped, unclenching her hands slowly.

"What?" he asked.

"I shall kill Captain Rydal," she

declared. "It is the only thing I can do. Will you force me to do

that, or will you help me? You have sledges and many dogs, and we

will pay. And I have judged you to be—a man."

He rose from the table, and for a

moment his face was turned from her. "You probably do not

understand my position, Mrs. Keith," he said, pacing slowly back

and forth and chuckling inwardly at the shock he was about to give

her. "You see, my livelihood depends on such men as Captain Rydal.

I have already done a big business with him in bone, oil, pelts—and

Eskimo women."

Without looking at her he heard

the horrified intake of her breath. It gave him a pleasing sort of

thrill, and he turned, smiling, to look into her dead-white face.

Her eyes had changed. There was no longer hope or entreaty in them.

They were simply pools of blue flame. And she, too, rose to her

feet.

"Then—I can expect—no help—from

you."

"I didn't say that, Mrs. Keith.

It shocks you to know that I am responsible. But up here, you must

understand the code of ethics is a great deal different from yours.

We figure that what I have done for Rydal and his crew keeps sane

men from going mad during the long months of darkness. But that

doesn't mean I'm not going to help you—and Peter. I think I shall.

But you must give me a little time in which to consider the

matter—say an hour or so. I understand that whatever is to be done

must be done quickly. If I make up my mind to take you to Fort

Confidence, we shall start within two or three hours. I shall bring

you word aboard ship. So you might return and prepare yourself and

Peter for a probable emergency."

She went out dumbly into the

night, Blake seeing her to the door and closing it after her. He

was courteous in his icy way but did not offer to escort her back

to the ship. She was glad. Her heart was choking her with hope and

fear. She had measured him differently this time. And she was

afraid. She had caught a glimpse that had taken her beyond the man,

to the monster. It made her shudder. And yet what did it matter, if

Blake helped them?

She had forgotten Wapi. Now she

found him again close at her side, and she dropped a hand to his

big head as she hurried back through the pallid gloom. She spoke to

him, crying out with sobbing breath what she had not dared to

reveal to Blake. For Wapi the long night had ceased to be a hell of

ghastly emptiness, and to her voice and the touch of her hand he

responded with a whine that was the whine of a white man's dog.

They had traveled two-thirds of the distance to the ship when he

stopped in his tracks and sniffed the wind that was coming from

shore. A second time he did this, and a third, and the third time

Dolores turned with him and faced the direction from which they had

come. A low growl rose in Wapi's throat, a snarl of menace with a

note of warning in it.

"What is it, Wapi?" whispered

Dolores. She heard his long fangs click, and under her hand she

felt his body grow tense. "What is it?" she repeated.

A thrill, a suspicion, shot into

her heart as they went on. A fourth time Wapi faced the shore and

growled before they reached the ship. Like shadows they went up

over the ice bridge. Dolores did not enter the cabin but drew Wapi

behind it so they could not be seen. Ten minutes, fifteen, and

suddenly she caught her breath and fell down on her knees beside

Wapi, putting her arms about his gaunt shoulders. "Be quiet," she

whispered. "Be quiet."

Up out of the night came a dark

and grotesque shadow. It paused below the bridge, then it came on

silently and passed almost without sound toward the captain's

quarters. It was Blake. Dolores' heart was choking her. Her arms

clutched Wapi, whispering for him to be quiet, to be quiet. Blake

disappeared, and she rose to her feet. She had come of fighting

stock. Peter was proud of that. "You slim wonderful little thing!"

he had said to her more than once. "You've a heart in that pretty

body of yours like the general's!" The general was her father, and

a fighter. She thought of Peter's words now, and the fighting blood

leaped through her veins. It was for Peter more than herself that

she was going to fight now.

She made Wapi understand that he

must remain where he was. Then she followed after Blake, followed

until her ears were close to the door behind which she could

already hear Blake and Rydal talking.

Ten minutes later she returned to

Wapi. Under her hood her face was as white as the whitest star in

the sky. She stood for many minutes close to the dog, gathering her

courage, marshaling her strength, preparing herself to face Peter.

He must not suspect until the last moment. She thanked God that

Wapi had caught the taint of Blake in the air, and she was

conscious of offering a prayer that God might help her and

Peter.

Peter gave a cry of pleasure when

the door opened and Dolores entered. He saw Wapi crowding in, and

laughed. "Pals already! I guess I needn't have been afraid for you.

What a giant of a dog!"