15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

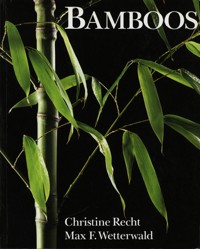

Bamboos are fascinating for their beauty, elegance and variety of form, not to mention their importance in the symbolism of Far Eastern poetry and art. Garden designers have for a long time recognised the many possibilities offered by this unique plant. Here the reader is offered all the information they need to grow bamboos in garden, on balconies and terraces, in conservatories and even in roof gardens. Fascination with bamboos has led many gardeners to buy them but ignorance of their requirements has often brought frustration and despair. This book aims to correct that situation and offers a major source of detailed reference and inspirational colour pictures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 208

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

BAMBOOS

BAMBOOS

Christine Recht and Max F. Wetterwald

edited by David Crampton

translated from the German by Martin Walters

Frontispiece:

‘Grass, bamboos, orchids and rocks’, Chinese fabric-drawing, Lu Kunfeng (1980)

Published as eBook in the United Kingdom in 2015

First published in 1992

Reprinted 1993/1994/1995/1996/1998/1999/2000

First published in paperback 2001, reprinted 2002

Translation © B.T. Batsford Ltd 1992

German edition © 1988 by

Eugen Ulmer GmbH & Co.,

Stuttgart, Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd

eISBN 9781849942133

Contents

Foreword

1Bamboos in Asiatic Culture

2Uses of Bamboo

3Morphology and Structure

4Characteristics of Bamboo Genera

5Species and Cultivars for the Garden

6Planting and Cultivation

7Garden Design

8Growing Bamboos in Containers

9Bamboo as a Raw Material

10Problems with Bamboo Cultivation

11Bamboo as a Vegetable

Appendix

General Index

Botanical Index

Foreword

Bamboos are fascinating plants – fascinating in their beauty and elegance, in their varied shapes and in their unusual qualities. Bamboos are simultaneously hard and soft, their stems are straight and yet flexible, their leaves graceful and green all year. Small wonder that these plants, which are already in vogue in America, are getting more and more popular in Europe.

Most bamboos come from Asia. There they are important in everyday life. All kinds of use is made of them – their shoots are eaten and bamboo groves are a feature of the natural landscape. Bamboos also influence the art and culture of many Asian people. In China they are seen as the embodiment of the Chinese way of life: yielding, yet always victorious.

In Europe, bamboo is mainly a decorative plant, an exotic that survives our climate and fits into the landscape. Many species are frost-tolerant and decorate our gardens in winter with their soft foliage. Bamboos can be used in so many different ways, like scarcely any other group of plants. They fit into both small and large gardens, where they can grow in groves, as a hedge, and also as individual plants. They can therefore be used both in a supporting role and as a main performer in the garden. They are effective on terraces, balconies, in conservatories, and even on roofs.

More and more nurseries offer container-grown bamboos. Some outlets have specialized in bamboo propagation and now have a hundred or more different species available. Bamboos are very beautiful but until recently we have not known how to deal with them effectively. Fascination with bamboos has led many gardeners to buy them, but ignorance of their requirements has often brought frustration and despair.

This book will therefore help all bamboo enthusiasts. It will explain how to treat these magical plants and point out which sites suit particular bamboo species well and where they look best. It will increase understanding of these fine plants and enable gardeners to succeed with them by understanding their particular requirements.

When writing about bamboos one feels rather like the bamboo painters of ancient China who said: ‘If you want to paint a bamboo you have to become one of their kind.’ It is particularly difficult to write a book about bamboos in Germany and to collect together the basic information, because there are so few experts.

I should like to thank all those who have helped me with their knowledge, experience and passion for bamboos: Werner Simon, Marktheidenfeld, who as co-author collated and described all the species that can be cultivated in Germany; Albrecht Weiß from Seeheim-Jungenheim, who put his extensive knowledge and long experience of bamboos at my disposal and who also infected me with his enthusiasm, as did Ullrich Willumeit, Darmstadt. Thanks also to Dr. Warda of the New Botanic Garden, Hamburg where Max Wetter-wald was able to photograph bamboos, and to Wolfgang Eberts, Baden-Baden, who always knew the answers to particular problems as well as the most beautiful bamboo gardens to photograph.

Christine Recht

1

Bamboos in Asiatic Culture

‘Bamboo is my brother’, so goes a Vietnamese proverb. This demonstrates precisely the relationship of almost all Asiatic people, even today, with this plant. From China to India, from the moist, primeval forests to the cool mountain foothills, bamboo is such a natural partner to humans in all walks of life that to live without it is scarcely imaginable. It is quite possible not to eat meat, but not to be without bamboo’, so said Su Dongpo (1036–1101), the greatest poet and artist of the Song Dynasty. It goes deeper than this, however. In ancient China people identified with bamboo, the symbol of the Chinese way of life. Bamboo stands for elasticity, endurance and tenacity. Bamboo bends in the breeze, but does not break. The leaves are moved by the wind, but do not fall. Bamboo therefore survives and conquers.

In Japan this characteristic is still known as a ‘bamboo mentality’: to make compromise, to yield, and eventually to go forward unbroken from all contests. In Asia bamboo embodies the ideas of Taoism, laid down mainly by Laotse. These ideas describe the art of survival as yielding and then coming back again.

Religion and symbolism

In all Asiatic countries religion is closely connected with nature. The gods, of which there were and still are countless numbers, lived in the rocks, in the water, woods, and hedgerows. Individual stones, rivers and trees were also held to be holy, although not in the European sense of the word. Water, mountains, plants and animals were seen not as inferior to humans but as part of a whole, to which people also belong. The belief that humanity cannot exist without nature, and that we must live by its laws in order to survive is still held in modern Asia. With this appreciation of the unity of humanity and nature one can understand why in Asia bamboo is considered as a friend, or a travelling companion.

It is not only bamboo that plays a leading role in Asiatic religion, philosophy and art; pine, willow, plum, lotus flower and chrysanthemum are also important. But of all these symbolic and revered plants, it is the bamboo alone that is put to practical use, be it as building material, food, or for making thousands of objects in daily use. Bamboo is of special significance in Asiatic, and particularly Chinese, symbolic language. It droops its leaves because its inner self (that is its heart) is empty. An empty heart in China means modesty, so bamboo is a symbol for this virtue. Bamboo is evergreen and does not change its appearance with the seasons. It is therefore held as a symbol of age. The Chinese character for bamboo is similar to that for laughter, because the Chinese believe that the bamboo plants bends when it hears laughter. In Chinese, the words for bamboo, prayer and wish all sound the same. The reason is as follows: sticks of bamboo explode if placed in a fire, with a loud crack. The bamboo firework was supposed to drive away demons and ensure that the gods heard prayers and wishes for peace and tranquillity.

In Asian art bamboo is often illustrated together with orchids or plum blossom. The flowers embody woman – or yin, the female element, bamboo the man – or yang, the male element.

Because bamboo plays such an important role in people’s lives in Asia, in philosophy as well as in everyday practical life, it has become a part of legend, belief and superstition. There are countless fairy-tales and legends in Asia concerning bamboos. Here is an example: When a Japanese farmer was cutting bamboo he found a tiny girl inside a bamboo culm. He took her home and brought her up as his own child. She grew up to be one of the most beautiful and charming girls in the whole country. The emperor of Japan heard about her and wanted to marry her. However, the girl wrote him a letter saying that it was too great an honour for her and she decided to return to the bamboo. The emperor sent all his soldiers to find her, but without success, and in sadness at losing the bamboo girl he burned her letter on top of the mountain, Fujiyama, where the fire still burns to this day.

Thick bamboo forest of Dendrocalamus giganteus in Cibodas (Java)

Many Asian ceremonies, especially in Japan, are closely connected with bamboo. For example, only certain species of bamboo are used for making the equipment so important in the Japanese tea ceremony. In certain parts of Japan there is also the ‘bamboo splitting festival’ which has been going since the eighth century. It is opened by priests with purifying ceremonies before the young men of the village start to split the fresh bamboo canes.

Traditional new year decorations in a Japanese house involve the three most revered plants: bamboo, plum and pine. These plants are known as the ‘three friends’ and they symbolize the three religious writers: Buddha (bamboo), Confucius (plum) and Lao Tse (pine). In China ‘four noble plants’ are respected: bamboo, orchid, plum and chrysanthemum. Together they stand for good luck and well-being and are present at all festivals, be these of a secular or religious nature. At the birth of a child, if the umbilical cord is cut with a bamboo knife this indicates a life of happiness. In Japan this privilege was earlier reserved only for the children of the ‘god-like’.

In Asia gods have human customs and requirements and are often depicted with very familiar everyday objects. Thus the immortal Ho sien-Ku is cooking rice with a bamboo spoon in his hand even as he is ‘redeemed and rises into the air’. He can be seen in old paintings with this bamboo spoon is his hand.

Bamboo brush and bamboo paper

‘His name may be written on bamboo and silk’ – so runs one of the many Chinese sayings. Bamboo has played a major role in calligraphy and artistic writing from very early times and calligraphy is still a high art form today. The pens used now, as in ancient times, to paint the characters are cut from bamboo stems. Paper used to be made from bamboo leaves and the shape of the leaf is still influential in Asian calligraphic work.

Calligraphy should not be seen simply as fine writing but as an art form that reached its highest development centuries ago, particularly in China. ‘Writing means picture painting and painting means picture writing’, so it is said in Asia. A calligrapher was therefore not simply a well-educated person who wrote text, but gave the text a particular quality through the artistic aspects of the script. It is possible to appreciate Chinese characters for their aesthetic attraction alone but the pleasure is deepened if one can also read the words, since content and shape are closely connected. The first recognizable Chinese characters are found in the thirteenth century BC. By then they were already simplified drawings reduced, so to speak, to shorthand. And so it is still today. Over the millenia there have been a series of calligraphic ‘schools’, each with its own famous master, who was both poet and artist. Many stories surround each of these, for example the story of the Buddhist monk Huaisu who lived around the year AD 725. He was so obsessed with his art that he painted characters on every surface he came across: temple walls, pieces of clothing, pots and pans. He even grew banana trees so he could draw on their large leaves. His eccentric style was described as comparable to ‘frightened snakes and sudden storms’. By contrast, the calligraphy of Wang Xizhi (307–65) was compared to mist and settling dew.

Splitting bamboo culms for painting and wickerwork

Eastern calligraphy takes its particular artistic form from the brush, known in China for about 6,000 years. From the beginning this was finely constructed: animal hair on a long, flexible bamboo handle. The hair was arranged in a wedge shape – thick at the base and increasingly thin towards the tip – so that both the finest lines and broad, powerful strokes could be painted. This brush shape has changed very little to this day. Just as unusual is the way in which the brush is used. It is held between the fingers, but the fingers and hand are not moved when writing or painting. The artist draws and paints from the elbow and shoulder, so that what appears on the paper comes direct from the centre of the body; that is from the heart. ‘The brush dances and the ink sings’ is still said of fine calligraphy and ink drawings. Whilst the brush is still made of bamboo today, in much earlier times so was the writing surface – thin bamboo blocks. These blocks were bound together to make the first ‘books’. Later on, painting and writing was done mostly on silk, until this ran out because of the high demand (China had special offices where writing and copying was carried out). Paper was discovered in China about 2,000 years ago. In 105 BC the court eunuch Tsai Lun told the emperor about a new discovery. A paste was prepared from old fishing nets, tree bark, hemp and grasses and spread out thinly on mats to dry. Archaeological remains show that paper had been made in a similar way from bamboo leaves at least two centuries earlier. The bamboo leaves were soaked in water and beaten all day until a thin paste resulted, which was poured out on to mats and dried. This gave thin sheets of paper which were then carefully smoothed out. Bamboo paper, however, was somewhat fibrous and the ink tended to run; therefore more and more paper was produced from waste. This, as well as being cheaper, is perfectly suited to writing and drawing with ink.

Bamboo paintings, on a scroll (left) and on rice paper (right), a centuries-old tradition

With the discovery of paper the art of calligraphy really took off, first in China and later also in Japan. As well as the artists there were many copiers who copied famous and beautiful works of art and this work was held to be desirable and honourable. In AD 400 calligraphy was taken from China to Japan, and many scholars and artists fled to Japan and settled there. Japanese artists refined calligraphy almost to the point of abstraction. There was also a simpler script that was felt by the artists to be too ‘primitive’ for them. This was taken up by many noble ladies, which explains why many famous works of Japanese literature were written by women.

First in China, then in Japan and other Asiatic countries, painting developed in parallel with calligraphy. A well-written text is often accompanied by symbolic ink drawings which relate to the text. The large, often metre-long, hanging pictures often have an explanatory text or poem in fine calligraphy. In Asia, calligraphy, painting and poetry are not considered separate arts as they are in the West, but aspects of one art. A poet is a painter and calligrapher; a painter is also a person of letters.

The bamboo painter

Bamboo has long been portrayed on ink drawings and scroll paintings. This is because bamboo is characteristic of the Asiatic landscape, and nature is still the most popular subject chosen by artists, along with religious and courtly scenes. In China, nature is not presented in simple form; the artists wanting their pictures to express much more. A realistically painted landscape, however fine, is regarded as primitive, and the artists put much more into the composition. In Japan, by contrast, landscapes tend to be more realistic and colourful, but bamboo is still dominant because it is such a prominent part of the natural scene.

On the other hand, bamboo is also used purely symbollically, for example as indicative of the Taoist concept of yielding in order to overcome. The portrayal of bamboo, orchid, plum blossom and chrysanthemum (the four noble plants) and lotus and pine developed into a particular genre, held above all others, in the Yuang period of China. There were special bamboo painters who concentrated on the representation of bamboo. Three of the most famous were Zhao Mengfu, his wife Kuang, and Gao Kegong – all living around AD 1250. These artists, like many others, accompanied their ink drawings with poetic verses. The drawings, mostly in black ink, or more rarely painted with blue-green, are very spiritual, capturing the character of bamboo through concise suggestion and they have great radiance. ‘In order to paint bamboo you must become bamboo’ say the bamboo artists.

There were also specialist bamboo painters in Japan. They simplified the themes still further, following Zen philosophy, emphasizing the symbolism and cleverly refining their paintings following the lifestyle of the Japanese imperial court.

Bamboo poets

Just as scroll paintings and ink drawings became increasingly simplified and symbolic, so too did poetry. In Japan, Haiku is still popular. This is a rhythmic three-line poem that expresses a particular atmosphere in few words. A Haiku poem describes, as it were, the scene presented by an instant, yet incorporating past and future. Naturally the ever-present bamboo features in many Haiku pieces.

Gardens in China and Japan

Bamboo plays an important role in Chinese and Japanese gardens. To understand this, one needs to appreciate the significance of gardens and garden art in these countries. Garden design is considered an art form similar to landscape painting, and is carried out according to a comparable set of rules. (There are fundamental differences between Chinese and Japanese garden art, but it would take us too far to go into these here. The reader should investigate the extensive literature.) In Asia there has always been a particular fear of wild, untamed nature, yet simultaneously a strong love for it and a feeling of unity with it. Nature and humanity are seen as indivisible. Gardens should reflect nature, but also provide people with the chance to immerse themselves in nature through meditation. A garden is therefore strongly symbolic. Chinese gardens are works of art in which landscapes are set up, not to imitate nature, but to simplify it and render it more profound, as in painting. A Chinese or Japanese garden is scarcely comparable with a European garden, because it is based upon a different set of assumptions. Chinese and Japanese gardens create a landscape that stimulates the imagination rather than the understanding. One sees over and over the juxtaposition of Yang and Yin, the masculine and feminine, hard and soft; for example rock and water, bamboo and chrysanthemum, straight and curved lines.

‘Two waders after rain’, ink drawing by Lu Kunfeng (1980)

In 1634 Yuan Jeh wrote this about gardens: ‘A single mountain can have many effects, a small stone can awaken many feelings. The shadows of dry banana leaves draw themselves wonderfully upon the paper of the window. The roots of the pine tree force themselves through the cracks of the stone. If you can find peace here in the middle of the city why should you wish to leave this place and seek another?...’ All things in Chinese gardens – and in still more refined and abstract form in Japanese gardens – have symbolic value and are aids to meditation. Water is always present, standing for human life and philosophical thought. There are no lawns, but gravel beds instead. Rocks symbolize mountains. They are often raised up high and particular value is laid on bizarre and steep formations. They represent, in contrast to water, the might of nature. Flowers are never planted in groups or patterns but stand isolated, to aid meditation. The chrysanthemum, which flowers late and is frost-tolerant, symbolizes culture and retirement, the water lily is the sign of purity and truth. Bamboo stands for suppleness and power, true friendship and vigorous age. The evergreen foliage of bamboo also provides a background for plum blossom and makes an artistic picture together with pine. In Asian gardens bamboo is usually thinned so that individual stems can be seen clearly, and a bamboo with many stems represents an entire forest.

Bamboo, water and pagoda roofs, a place for meditation. Daguanlou Park, Kunming, China

In Japan, gardens are arranged so that they relate to living quarters. The sliding panels of traditional Japanese houses open onto the garden and the garden is designed so that when the panel is opened it appears like a painting, in which deep meditation is possible.

In the sixteenth century Japanese gardeners refined their art so much that gardens were laid out with scarcely any plants at all. A rock symbolized a mountain or waterfall. The water was indicated by fine sand or gravel, raked to give patterns symbolizing a flowing stream, surging river or open sea. Such dry gardens can still be seen today and they often contain just a few particularly fine bamboo stems. They are not walked in but are simply admired from the house.

Artistic gardens were laid out in temple grounds. The bamboo hedge of Hokokuji Temple in Kamakura is famous. Here, individual moss-covered stones and stone lanterns lie between giant bamboos. Bamboo hedges round temples contain particularly rare or fine bamboo species. In Kochi in Japan there is a hedge of the rare ‘golden bamboo’ which has golden-yellow stems with green stripes. This has been placed under special protection as a natural monument. Hedges of ‘tortoise-shell’ bamboo are also well known and often visited.

2

The Uses of Bamboo

Bamboo is a plant which accompanies people throughout their lives in Asia and for this reason it plays a big role in Asiatic culture. Asian people, more than half the population of the world, use bamboo for building their houses, as containers for food and drink, for making all sorts of household and agricultural implements, for making weapons, as food, animal fodder, and as medicine.

The British Colonel Barrington de Fonblanque, who travelled in China in the last century, summarized his impressions thus: ‘How could the poor Chinese survive without bamboo? It supplies not only nourishment, but also the roof of his house, the mat on which he sleeps, the cup from which he drinks, and the chopsticks with which he eats. The Chinaman waters his fields using bamboo pipes, gathers in his harvest with a bamboo rake, purifies the grain with a bamboo riddle and carries it home in a bamboo basket. The mast of his junk is made from bamboo, as is the axle of his barrow. He is whipped with a bamboo rod, tortured with bamboo splinters and eventually strangled with a bamboo rope.’

The importance of bamboo in Asia has not been diminished by the impact of modern technology. The qualities of this plant are such that it cannot very often be replaced, even with modern substitutes. A bamboo pipe is as strong as steel, but more malleable. It grows tall and straight and is therefore perfect as a building material. It is light and hard, flexible and tough. It is difficult to set on fire and can be bent under heat, retaining its shape without losing its strength and elasticity. It can be split into the finest fibres, from which an almost unbreakable kind of rope can be made. The shoots are a vitamin-rich delicacy and the leaves provide nourishing animal fodder.

Thick bamboo forests are an integral feature of every Asian landscape, from Japan to India, from the equator northwards to 40 degrees latitude, from tropical rain forest to the cool foothills of the Himalayas. The dry rustle of their narrow leaves is, together with the fizzing of cicadas and the noise of frogs croaking, the characteristic sound of a tropical evening.

Cultivation in commerce andagriculture

There are 1,050 to 1,070 different species of bamboo, from the tiny species of Sasa to gaint subtropical bamboos up to 30 metres tall with a diameter of 30 cm (12 in). Only a few species are cultivated in commercial plantations. In Japan, where there are about 100 species, only about 15 species are widespread and in cultivation. Ninety percent of all bamboo plantations in the land of the rising sun consist of ‘Madake’ (Phyllostachys bambusoides) and ‘Moso’ (P. heterocycla f. pubescens). Madake is mainly used for building, Moso for food, since its shoots are considered the finest of all.