18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

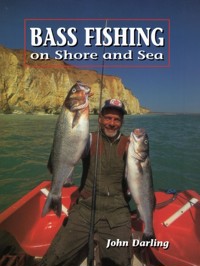

The result of more than thirty years' experience, Bass Fishing – on Shore and Sea is a comprehensive guide to catching this beautiful yet challenging gamefish. Illustrated throughout with superb photographs, this book is essential reading for all sea anglers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in 1996 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2012

© John Darling 1996

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 439 6

All photographs by John Darling.

Frontispiece: Fighting a big bass on an Irish storm beach.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword by Ron Preddy

Introduction

1 Biology and Physical Characteristics

2 Shore Fishing

3 Where to Find Bass Inshore

4 Reefs and Rocks

5 Baits

Plates

6 Boating for Bass

7 Fishing Offshore

8 Lures

9 Conservation and the Future for Bass

Index

Foreword

This is a book for those who already love to catch big bass. It is also aimed at the less fortunate among us who have yet to catch such a fish, but would dearly love to. These two groups probably include every angler who has ever cast a line upon the sea.

Imagine the scene: dawn’s first light reveals the dark curve of a carbon bass rod responding to the power of a silver-plated turbo-charged beauty beneath the waves. At long last, as if conceding defeat, the double-figure bass turns and glides majestically towards you, under the clear blue surface of a windless sea. The hookhold appears secure and the waiting net reaches out to secure the prize. For an instant, the eyes of the captured meet those of the captor. There is a brief pang of concern before the victor becomes aware that his specimen is safe. He cradles the beautiful fish in a manner befitting his own first-born, unable to believe his good fortune. The rush of adrenalin prevents him from putting a bait back into the water for some while. It is a magical experience that no word could properly express.

Big bass have become near-mythical creatures, but while accepting that they are extremely difficult to locate and catch, it must be said that the task is far from impossible. They vary their habitat according to instinct and opportunity. For every fish that cruises up-river under cover of darkness to wreak havoc in the shallows at first light, there are probably six more patrolling the weedy margins of a jagged reef just offshore. Seemingly programmed to avoid extinction, most big bass now favour the relative security provided by the thousands of shipwrecks dotted far out towards the beckoning horizon.

To catch quality fish from such a wide variety of angling opportunities takes an angler of the highest calibre. Those who make a study of such things realize that the specialists catch the vast majority of these fish. The author of this treatise, John Darling, is such an angler. He has written a highly informative book, revealing the amazing insights that he has accumulated in a lifetime’s loving pursuit of a most demanding mistress. John and I have fished together for many years and have shared several outstanding catches of large bass. If, like me, you believe that big bass are the stuff of dreams and a worthy goal to strive for, then this book is for you.

Ron Preddy

Introduction

Catching bass is my passion. It occupies my thoughts for most of the summer and much of the winter, at any time of the day or night. Years ago a friend told me that if I spent as much time thinking about business as I spend thinking about Dicentrachuslabrax, I would be a millionaire. I bet I would not have had as much fun as I have in more than thirty years of bass fishing. I have been writing about them for almost as long. My first article on the subject was published in Creel in May 1964. It was inspired by one of the most remarkable anglers of all time, a devout bass angler and one of the world’s most gifted angling writers: Clive Gammon.

I owe a debt of gratitude to the many anglers who have given me snippets of information that have increased my understanding of bass and how to catch them. Some of these people are noted angling writers; others are anglers I have chatted to on the beach and around the harbour. Some old friends are now in that anglers’ heaven where each bass is progressively larger and fights even harder, but they have to wait a tad longer for each one to strike.

Many anglers and boatmen have given me ideas to contemplate and tips to put into use. Some people have given me profound insights into bass behaviour, without realizing it. The tiniest scrap of information can be very valuable, particularly when it is the last piece of a jigsaw or confirmation of a suspicion.

Our hero, Dicentrachuslabrax, the most sporting fish in British seas.

The bass is known throughout Europe, in various languages, as the ‘sea wolf’, or ‘sea perch’. It is an exceedingly handsome, powerful fish, a total thug and a voracious predator. It gleams like a bar of precious metal and has a scorching turn of speed. Its power and aggression have caused it to be prized as one of the foremost game fish of the sea. For this reason, sport anglers hate commercial fishermen who have scant respect for their quarry, either alive or dead, and leave these noble fish to flap out their last gasps in the muck and grime at the bottom of a boat while they go about the business of catching more.

For shore anglers, bass are to be caught from some of the most awesome scenery anywhere. Whether they are running a rolling Atlantic surf on a wild storm beach where the mountains rise jagged against the sky, or striking baitfish behind a ledge that juts out beneath towering cliffs, bass anglers see coastal scenery at its best and all the spectacular shades of light and weather. As sunset fades, is there any better place to be in the world than on an immaculate, wild beach, with the breeze shrilling in a taut line and the savage, thumping strain against the rod of a nine-pounder?

Certain events mark the progress of a bass angler’s addiction. When I was very young, I watched an angler pull in a six-pounder from a rocky cove. I was so impressed by its power, grace and beauty that I resolved to catch one myself. The first bass I handled was a two-and-a-half-pounder that I swapped for a whiting livebait with an angler who did not eat fish. The first bass I caught was a schoolie; the second one weighed 8¼lb. The third, the following night, weighed 10¼lb. “I’ve got it sussed”, I thought but I rapidly discovered otherwise. As each new season dawns, I still feel I am starting on a fresh adventure.

Bass have brains and anybody who fails to remember that will catch very few. Bass are clever enough to avoid trammel nets in clear water, and to see through clumsy attempts to catch them on rod and line. Of course, they do daft things at times; but not often. The moment you start taking short cuts while hunting wild quarry, is when failure starts edging in.

You have to be single-minded and ignore sleep and tiredness to catch big bass. You have to clamber out of bed at ridiculous hours, heave rocks for crabs and expend a great deal of energy. Bass are caught most consistently by anglers who visit their marks frequently, who keep tabs on the fish’s movements and who get a feel for the area that they fish. There are no fast tracks to success. Catching big bass requires time, hard work, patience and attention to detail. Each season a fresh stratum of experience is laid down, and over the years you develop an instinct for where to find bass and how to coax them into accepting your offering.

That is only as it should be because bass are such wonderfully sporting fish. They have an awesome turn of speed which they use to kill mackerel or smash the line of the unwary angler. It is only right that anglers should serve an apprenticeship, so that they can develop their skills, and fully savour the moment when they have fought an enormous fish to a standstill and ultimately draw it into the landing net.

This book is not a basic angling primer. It assumes that a certain amount of knowledge has already been acquired. Neither can I state places to fish or where to find bait because that would make me very unpopular with a lot of anglers. Bass anglers are an odd lot, coming from all walks of life but united by a desire for the wild, unspoilt shorelines or the remote loneliness of a calm sea beyond the horizon. We share our secrets with our friends but hate it when strangers discover our marks. We owe thanks to people like Donovan Kelley, MBE, who has worked so hard in the interests of conservation. He undertook the painstaking research into bass long before anybody else took much interest. His findings have proved immensely valuable, especially with regard to the nursery areas.

This book is dedicated to every angler who feels that inner agitation when a warm breeze stirs the surf and sets the trees sighing and creaking, or when the sea is a glittering calm and the birds are pounding baitfish along the edge of a reef, or when dusk steals over the shore line as the tide laps lazily at the rocks and the line draws suddenly tight.

1 Biology and Physical Characteristics

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Bass are almost impossible to confuse with any other European species of sea fish. Once seen, their appearance will never be forgotten. Their colour sometimes changes according to habitat. Although the belly is always silvery-white, the backs of bass caught over sand are often very pale, while those from reefs and offshore wrecks are usually very dark – almost black. This comes about because the fish can adapt their colour to blend into the background. Infant bass often have little black spots, which occasionally persist into adulthood. Very rarely, one encounters specimens with a yellowish hue over the back and flanks.

The shape of the head may sometimes vary, too. The head of most bass is usually pointed, but that of some is much more blunt. This foreshortened appearance makes them look as if they have received a punch on the nose at some time.

Anglers should beware that bass have a way of taking revenge on their captors, who should approach them with caution and handle them with care. An aggressive bass will raise its spiny dorsal fin and flare its gill cover to make two razor-sharp bony plates – the opercula – stand out. These plates can make nasty cuts on wet hands, and if a spine jabs you and the tip breaks off, the wound will linger for a long time.

Plump winter bass like this prefer large baits anchored to the sea-bed.

DISTRIBUTION

Most bass fishing is practised to the south of a line imagined between Morecambe Bay and The Wash, though some are caught from the Solway Firth and the mouth of the River Luce on the west coast of Scotland. Some are caught in Yorkshire and a few have been taken as far north as Aberdeen. In Ireland, most bass are found south of a line between the estuaries of the River Moy and River Boyne. Their range extends southwards as far as Morocco, and eastwards throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Bass have been caught all round Scotland at one time or another, some large ones, but not in any abundance. This might be set to change with what some scientists are calling global warming. Fish from abundant year classes are caught all round the British Isles, as far as the north of Scotland. As adolescents, they range over a wide area and may restock some fished-out areas. Global warming may induce bass to over-winter farther east than normal, perhaps off Beachy Head and in the lower North Sea.

Bass happily forage for food in any depth of water from the fifty-metre line (as provided by marine charts) up to the inshore shallows. They will often hunt in water that is barely deep enough to cover their backs. They are also one of the few marine species adapted to living in brackish water and can even cope with river water that is bordering on fresh.

The large mouth and crushing jaws of bass make short work of baitfish.

They are powerful swimmers, but that does not mean that they are particularly willing to ride strong currents. They find eddies and areas of slack water close by. They conserve energy for when (with powerful sweeps of the tail) they dash into the attack keeping every other fin flattened against the body. The main reason why bass strike spinners and plugs so violently is that they launch themselves like missiles at lures.

THE MOUTH

The bass’s mouth is so large that it dwarfs big hooks. It is noted for being decidedly bony and lightly covered with a thick leathery skin that can be penetrated by only the sharpest of hooks. The outer part is like a pair of bellows. The maxillary jaws extend forwards, but are connected to the skull by only a thin membrane. The hook often lodges in this membrane, which tears slightly under pressure, forming a small hole. The bigger the fish and the harder it fights, the bigger the hole will be. All the fish needs is a bit of slack line as it lies on the surface, and it is likely to thrash around in every direction and throw the hook. I have seen it happen time and time again, particularly while landing fish from a boat.

In a moment’s loss of concentration, while reaching for the landing net or watching your friend go to slide it under the fish, you forget to keep the line tight. In an instant, the bass thrashes its head and throws the hook. The fish sinks in the water then realizes it is free. With a few sweeps of its tail, it dives and disappears from sight.

Big bass can only be beaten with a bent rod and a tight line. It needs to be tight to the fish not the lead weight. That is how a friend of mine, who is new to bass fishing, lost an eleven-pounder last summer. It was a memorable fish, not least because we were fishing a local specimen competition. It would have cleaned up a lot of prizes.

SENSORY PERCEPTION

Bass have excellent eyesight. Their large, expressionful eyes cover 360 degrees, and are very quick to spot potential prey and assist them to catch it at lightning speed. They have little trouble seeing anglers moving against the skyline. It is advisable to keep low or out of sight when fishing clear shallow water, as though you are fishing a stream for chub.

At night it is most unwise to use a light that shines over the water. Although bass use bright lighting to silhouette their prey, I doubt if they are attracted to lights for any other reason. The flash caused by a torch shone out onto the water, or by somebody walking near a Tilley lamp, is likely to frighten them. They often swim close to the angler’s feet at night, and a misdirected beam of light at the wrong moment might make all the difference between a successful trip and a blank. Even when landing fish, it is wise to keep the lights off. Use whatever is coming from the night sky when directing a fish into the net.

A fifteen pounder, caught by a specialist bass angler.

Bass have frequently shown that they spend a lot of time in a small area, so it is quite possible that they take a dim view of finding a bright light where none should be. Most night bassmen carry a small torch or headlamp and only turn it on when they are facing away from the sea. On a big beach, a pressure lamp at a base camp above the highwater mark is acceptable, provided that it is a long way from the fishing area.

The bass’s senses of taste and smell are highly developed, and it may use them to map migration routes. It is certainly very good for locating big, juicy baits of squid, mackerel and crab, but they do need to be big and juicy. Because bass feed more by sight, their sense of smell is not as good as that of an eel or a dogfish.

Nobody really knows precisely what vibrations bass pick up on their lateral line, but their sonar system certainly enables them to swim around in rough, murky conditions at night without any trouble at all. Under these conditions, bass rule the roost in European waters because they are safe from sharks, seals, porpoises and nearly every other predator, except man. During the day, it is possible that the bass are summoned to dense masses of baitfish by the sound of mackerel, bass, garfish and other predators striking the fish, by the sound of baitfish as they endeavour to escape, and by the sound of splashing, dive-bombing sea birds.

The bigger the fish, the bigger the swim bladder, and the more it resonates with underwater vibrations (and the better it shows up on the fish finder). These vibes are fed to the inner ear by a chain of small bones. The implication is that bass can ‘hear’ better as they get older and wiser, so they are increasingly likely to be more scared of the noise of sport-fishing boats

Nowadays bass rarely tolerate boats whizzing around them unless they are in a feeding frenzy. Sometimes anglers are too keen to catch them. Just when the birds are starting to work, somebody goes charging through them in his boat, anxious to begin a drift. The fish go down, the birds drift away and another golden opportunity is scuppered by ignorance.

Rock ledges like this enable bass to be caught by a wide variety of methods.

In common with cod, bass are circumspect of an anchored boat. In calm water, you can easily see the wave of disturbance that the hull sends out to each side and this seems to disturb the fish. They also dislike the vibrations coming from the anchor rope. If you imagine the boat as a soundboard, as on a guitar, and the anchor rope as a single string, it is easy to appreciate that the presence of a boat can disturb the bass.

For this reason up-tide casting is widely practised, casting baits away from the hull and out of the zone of disturbance. When riding at anchor in a small GRP bass boat and fishing with rods in rests, the tide acting on the line causes it to sing in an eerie manner, like the singing of distant whales or an old woman humming. It sounds quite loud on calm days, but it does not seem to upset the fish.

HABITAT

People and boats are most active during the day, and for this reason many harbours and estuaries are devoid of bass of any decent size by day. However, such places are good larders, full of small fish and crustaceans, and the bass know it. They visit under cover of darkness, coming in with the tide when everything is quiet. At high water around two o’clock in the morning is a good tide for these bass.

Bass feel more secure and feed throughout the day in deep water, offshore – 75–100ft (23–30m). While in shallow water inshore – 20–30ft (6–9m) – they may be disturbed by bathers, li-los, surf-boards, jet-skis, boats, water-skiers, ferries, nets, and other unnatural goings-on. Unless the shoreline is rarely disturbed, I suspect that some bass hole up during the day in deep gullies among reefs, inside wrecks and within the structure of seaside piers (the ones that stand on stilts). The exception to this general rule is when baitfish are around. Bass refuges are also baitfish refuges, and although the bass may not be hunting very actively, they are unlikely to pass up an easy meal.

In many areas, inshore fishing with bait is generally more successful shortly after dawn or as dusk comes in, but a lot of good bass have been caught on plugs and spinners within a short distance of the edge during bright, calm, sunny conditions. I have also caught them from the rocks on crab under similar circumstances. On a few occasions I have caught them from the surf in bright, sunny weather. However, bass do appear to have become more circumspect about their daytime activities over the years. This, fortunately, permits anglers to ambush them when they leave their lairs at dusk.

Night fishing in autumn, with a large squid bait just beyond the waves.

Bass that are large enough to interest anglers can be found in a wide variety of habitats: seething surf, tide-races, rocky bays and headlands, around sandbanks, reefs, wrecks and inside estuaries where they penetrate upstream to where the water is brackish. Each of these different areas will be dealt with in greater detail in a later chapter, but they all share one factor in common: they are places where bass can find their prey at a disadvantage.

Bass shelter from raging spring tides in large estuaries, in harbours, around large reefs and the largest wrecks. They do not relish very rough seas, big swells or heavy undertows. I have caught more bass in calm seas and gentle surfs than I ever have in rough weather, other than by seeking out sheltered corners. Middling tides and more gentle conditions generally produce the best catches. Local knowledge should be heeded, but some local habits may have grown out of laziness rather than perspicacity. Bass are often caught by anglers who ignore local knowledge and follow their own instincts.

Bass will tolerate a wide variety of temperatures, but prefer water around 10–20°C (50–68°F). Fish in estuaries and shallow water move to slightly deeper more comfortable water when the air temperature drops sharply, and they are attracted into sun-warmed shallows, particularly early in the season when the sea is still warming up. It is well known that bass are attracted to warm-water outfalls, like those from power stations and industrial cooling plants. These warm outlets are favoured by juvenile bass, which often spend the entire winter close by them. In autumn, as the sea cools, adult fish migrate to deeper water, down to 260ft (80m) off the south-west of England, where the temperature is more constant, and they spend the winter there.

Rustington Beach, 1950: my first ever crabbing expedition.

Algal blooms are a problem. Unfortunately it seems that theses are being encouraged these days by the amount of pulverized sewage that is being pumped into the sea. Algal blooms reduce oxygen levels considerably and are absolutely no good for bass fishing. The bloom eventually sinks. Divers tell me that the sea can look clear on top, but down below there is a thick layer of algae which blocks out the light.

MIGRATION

A few tagged fish have been found to travel large distances in a short time, suggesting that they swim quite fast while migrating, possibly 20 miles (30km) or more in a day and 150 miles (240km) in a week. Tagging has shown that some fish cross the Western Approaches between England and the coast of France, although it is no longer believed that there is a mass migration of what used to be referred to as ‘Biscay bass’. There appears to be no mixing of Irish and British stocks, suggesting that they do not migrate across the Irish Sea. They are rarely found more than 50 miles (80km) offshore but have been trawled up from 180ft (55m).

Many species of fish migrate by making use of tidal currents. This is called ‘selected tidal stream transport’. The fish use the tide to carry them over towards their destination. When the tide changes and the current reverses its direction, they hunker down, get into shelter, rest and sometimes feed, while waiting for the tide to turn again.

When migrating, bass often form very large shoals offshore. Each May two or three vast shoals appear off Beachy Head in Sussex. These shoals can sometimes be up to a mile (1.6km) long, and are believed to be everybody else’s bass migrating up-Channel to Kent, the Thames Estuary, the North Sea and beyond. While migrating, the fish are generally to be found at one or two well-known marks for a day, with only a few stragglers remaining the following day. They appear to migrate under cover of darkness.

Years ago huge shoals like this could sometimes be seen close to shore, and seine netters working from beaches like Pendine in Glamorgan and some Cornish and Sussex beaches made large catches, sometimes of very big fish, but not any more. Nowadays trawlers working in pairs look for groups of bass boats on their radar and plough into the shoal.

Tagging has shown that most bass are remarkably faithful to their migration routes. The majority of fish that are tagged in a specific area are caught in the same area, within 20 miles (30km), over succeeding years. However, some fish have been recaptured hundreds of miles from their tagging site. One from the Thames Estuary was recaptured on the north coast of Spain after a journey of about 600 miles (950km).

When the sea pinks come into bloom, the crabs are peeling and the bass return to the reefs.

Little can be deduced from this. It might have been a fish from Biscay that travelled north to feed (a journey it could achieve in little over a fortnight); it might have originated in Brittany; it could have been an English bass. Maybe it had developed a taste for young tuna, which would be in keeping with the bass’s buccaneering spirit. In the end, evidence points to the fact that most bass stick to the same migration route year after year once they mature.

Casting into a gentle surf on Inch Strand, Co. Kerry. Bass now receive some measure of protection in Ireland.

After spending four to five years of their childhood exploring a particular patch of territory, it is not surprising that bass return to it in each successive migration. This bodes ill for conservation. If bass stocks are wiped out through overfishing in a specific area, there is little chance of mass recruitment from outside areas. Bassmen everywhere can testify to an overwhelming pile of evidence to show that this has happened, and is still happening, around the British Isles. Other species, particularly birds, return to the same square yard where they were hatched after spending months at sea, circumnavigating the world. Many wild creatures memorize maps of where they live. Woodpigeons, for example, spend two months showing their young around their home patch so that they memorize the landmarks. We have yet to discover precisely what steers bass around the unimaginably huge expanses of sea – magnetite perhaps, in the pores of the lateral line, like salmon, or perhaps they recognize the characteristic smell of their home range.

The movement of bass around the British Isles is understood well enough, from the angler’s point of view. In general terms, the first bass of the year can be expected in late February in Cornwall, and in the West Country and the Channel Islands in March. April sees the first fish in Sussex and the Thames Estuary, but for most of us it is May before catches become reliable. In June and July bass are everywhere, on into August, September and October. Some are caught in November and occasionally in December, further west. They are caught in December in Ireland where the Gulf Stream brushes the shore, although the best times for the Kerry surf beaches are January to June and then again in the autumn.

As a general rule, bass from the North Sea and the English Channel drift south and west in October, November and December, while those along the west coast drift south. The bass around Cornwall seem to hang around the vicinity throughout the year. The migration would appear to start earlier on the west coast, in September. By January, bass are somewhere in the mild Atlantic between Cornwall and Brittany.

Years ago my friends and I used to catch the occasional 7–10lb bass around Christmas and early in the New Year from beaches in Sussex, which suggests that some fish might have been over-wintering in deeper water farther from shore. Most juvenile bass keep to within 30 miles (50km) of their home patch, but a few juvenile and adolescent bass yearn for the open road, as befits a species with a buccaneering temperament. They roam miles from home, particularly as they approach maturity. Big bass range farther as they grow older. Fish from the Thames Estuary and Anglesey have to travel in excess of 300 miles (480km) to their over-wintering area, and back again the next year. Some 12–15lb bass will have wandered thousands of miles during their lifetime.

The bass start to move north and east from their over-wintering areas in February, spawning as they go, but anglers don’t encounter meaningful shoals until May, when the fish have all but completed spawning and the water has warmed up sufficiently to induce feeding. This is when the scales first show signs of new-season growth. By mid-summer, nearly all of the bass will have returned to the same area that was to their liking the previous season. This naturally separates British bass into fairly specific groups.

PREY AND FEEDING

Bass are opportunists and readily exploit any source of food that comes their way. They are not above taking food waste that is thrown overboard from ships or is dumped from restaurants on piers, where they can be caught on balls of cheese paste. Years ago a Newhaven angler used to thread baked beans up his hook and onto the line, and free-line this offering among the slops that were thrown overboard from cross-Channel ferries. Bass regularly visit harbours and estuaries where fish waste is dumped overboard by netsmen.

A friend of mine, Digger Derrington, once caught a bass from a sewer outfall. It contained a drowned mouse. He set some traps in his garden shed, caught some mice, and ended up catching a 4lb bass on one of them Other friends have caught bass containing a packet of kippers (with its plastic wrapper intact), and a packet of cheese (also complete with its plastic packaging). This surely says something about the sensitivity of the bass’s sense of smell. They have been found with chicken bones inside them, and one perfectly healthy specimen was caught with a meat skewer sticking out of its flank. In time, it would probably have passed right through and the wound would have healed. After all, it is not uncommon to find boa constrictors with the horns of their prey sticking out of one side. Bass are often caught in crab and lobster pots, which they have entered, intent on filching the bait.

Inshore, bass tend to hunt in loose gangs, moving quite rapidly through an area and on to the next likely larder. I have seen shoals foraging over the sea-bed with their heads down, hunting for crabs, molluscs, fish, worms and anything else that looks edible. When they find shoals of baitfish, they set about them with a vengeance, driving them upwards and away from cover. These attacks are usually related to some sort of structure on the seabed, where the bass wait in ambush, and where the tidal currents put the baitfish at a disadvantage. They are usually picked off individually, but when the bass are numerous and so are the baitfish, I think that the bass drive into the shoals to stun them.

On several occasions while fishing in my boat over large shoals of feeding bass, I have observed dead sprats drifting away with the tide some 20ft (6m) below the surface. In calm conditions, the bass can be seen swirling at the surface, until some boat ploughs through and puts them off the feed. Years ago the shoals of bass were so thick off some parts of Britain that you could drive through them at full speed and still catch fish.

I once saw seventeen boats off Beachy Head complete the drift together when I was just starting. It looked for all the world like a powerboat race coming towards me. Often I have been drifting through a shoal of bass, with the gulls screaming and diving all around me, and have seen a sprat go dashing away just under the surface, throwing out a wake like a miniature torpedo. A gull has dived onto the fish, but a bass has got there first, and the desperate baitfish has disappeared amid a heavy swirl. By that time, my rod was usually locked over and bucking to a wildly fighting eight-pounder – or I would anxiously be wondering why it wasn’t.

Even in quite deep water – 100ft (30m) for example – the bass drive the bait upwards, and very often the seagulls can see the action going on beneath them. The bass go into a feeding frenzy, which is matched by the gulls. No other sight gladdens the heart of a bass angler more than that of a plume of seagulls, their white wings flickering in the early morning sunlight, working over a shoal of feeding bass – unless they are miles out of casting range. A feeding frenzy acts like a magnet to all other fish around.

Diving gulls often reveal where fish are feeding.

Years ago I anchored up very close in on a reef. I was fishing with some perfect crab bait, and I saw three other boats whizzing around a couple of miles farther out. The weather was blindingly bright, so I should have been spinning instead. As if to tell me that they were hunting for fish, two large bass swam up and closely inspected the dimples where my line entered the water. The boats offshore loaded up, but the fish were also close in and were on the lookout for prey.

Structure – wrecks, reefs and sandbanks – is not always essential. Sometimes bass find a shoal of baitfish on open ground, far from cover. Opportunities like this are more frequent than some anglers realize. The birds look as if they are working over mackerel shoals, but bass are beneath them.

The speed with which a bass attacks its prey can be awesome, particularly when you are fishing with livebait. For this reason, I don’t wait around much if takes are slow in coming. If the fish are there, I usually get an offer within minutes of casting out or dropping a bait down to them. I have often hooked bass within seconds of presenting my bait. When this is the first fish of the day, it usually foretells a hectic session. Unless the water conditions change, a lot more fish are likely to be down there waiting for the bait.

From the shore, however, you have to wait for the fish to move with the tide and be influenced by the much more changeable sea conditions that are found around the edges of the ocean. None the less, a similar sort of certainty can be expected from the shore. In many places, at a specific hour in the tide, the bass may come past and be willing to feed. Success at any method of bass fishing requires careful calculations and some input from the bass. They may not be obliging on seven trips out of ten, but those three successful sessions can be relied on to refuel your enthusiasm for at least another season.

The speed with which bass take is relative to the size of the shoal and the amount of competition among the individual fish, but it should also be noted that when there is little competition, as when fishing with crab inshore, the takes can be very slow. Under these conditions, the only indication that a bass is at the bait may be a light drawing on the line, or a slight tap such as a crab would give. Almost always, these gentle takes occur close to shore and where the current is negligible. I was taught very early in my bassing career that unless I could recognize these offers, I might miss the opportunity of the day. I have watched the rod-tip of inexperienced bassmen and have seen bass gently move it without the angler realizing that he has just had an offer. Having said that, a friend of mine was out in my boat on one of his first ever fishing expeditions, and his rod was dragged the full length of the cockpit. The only thing that saved it from being lost overboard was the reel, which jammed against a cleat at the stern. He turned to me, his eyes full of innocence, and asked, ‘Was that a bite?’.

One advantage of living in a shoal is that experiences can be shared. It often seems that every bass in a shoal is aware of what its colleagues are up to. This is most dramatically illustrated when a large, rampaging gang of bass is found feeding on baitfish and one is hooked. After the main part of the fight, as the fish is being drawn towards the bait, you might see that the rest of the shoal has followed the hooked fish. Sometimes it is hard to pick out which one is hooked because there are so many dark shapes swimming behind it. More often than not, the one with the bait is dwarfed by the fish swimming alongside it, some of them well into double figures.

This can be turned to advantage by flicking a spinner or other lure in front of the ones that have swum up to see what is happening. The twisting and turning of a hooked bass looks as if it is snapping individuals out of a shoal of baitfish. The others, keen to get in on the act, are naturally curious. Like mackerel, they can then be caught by the stringful.

However, I once found a school of tiny bass fry beside my boat and crumbled some bread into fine pieces to see if they would take. One of the basslings at the head of the shoal darted up, grabbed a crumb, tasted it, then spat it out. Another fish, farther back in in the school, went up and inspected the crumb from a distance of about an inch (2.5cm), dropping back with the current as it did so. Then it turned away and resumed its original position. After that the entire shoal completely ignored the breadcrumbs. At the time, it was getting towards low tide, and the barnacle-encrusted rails of a ladder had become exposed. I used the back of a knife to scrape off some barnacles, mashed them up and tempted the basslings once again. Recognizing the smell of blood (rather than yeast) they all piled in and gulped down the tiny scraps of meat.

A few days later, in Newhaven Marina, I found a freshwater outflow that drains into the river. It was high summer, and the flow of water was negligible, but I saw a few bass fry down there and decided to try an experiment. I popped into the Harbour Tackle Shop, where Dennis O’Kennedy donated a razor-fish to a good cause.

I shelled the razor-fish, then pulverized it and fed it into the water outlet. Within seconds, the bass fry were crowding round, and I whipped them into such a frenzy with the mashed razor-fish that it looked as if I had sprinkled silver Christmas glitter into the outfall. One of the advantages of feeding at speed is that the bass can get a lot down their gullet quickly.

When bass are hungry, they eat lots. They may go after a large number of individual items, like crabs or even tiny slaters and sand-hoppers, but sometimes they prefer to attack the biggest items of prey that won’t attack them first. Bass are frequently caught from estuaries, their stomachs hard and tight with shore crabs. One seven-pounder that I caught from the rocks had three 6in (15cm) wide soft edible crabs inside it. I have frequently caught bass on very large live and dead baits. Sometimes