2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

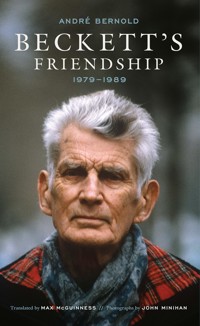

'Despite his deep sense of privacy, Beckett's persona has been so widely written about that it has become unavoidably mixed up in our imagination with what Bernold calls his "creatures". Whether or not Barthes and Foucault were right to dismiss the figure of the author, when confronted with Vladimir wincing or Krapp hunched over his tape recorder or Molloy resting on his bicycle, one's mind always seems to turn to the "gentle mask" placed over the "severe ossature" that has been immortalized in John Minihan's photographs, surely among the most iconic images of the twentieth century. We simply cannot help it.' (From the translator's preface) Meeting in the cafés and streets of Paris, with conversations noted and hesitancies observed, the gradual exfoliation of a personality is revealed across the last decade of Beckett's life as one intellectual appraises another. This is a charming and sympathetic study of one of literature's most opaque writers and of his interests in music, philosophy, visual arts and the spoken arts. In shedding sympathetic light on a famously private Irishman abroad, these verbal exposures complement John Minihan's contemporaneous and intimate black-and-white photographs, taken in the same environs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

BECKETT’S FRIENDSHIP 1979–1989

André Bernold

Translated byMax McGuinness

Photographs byJohn Minihan

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Dedication

For Josette Hayden, and for Bernard Pautrat

In memory of Nicolas Abt (1889–1965)

TO MY SON,

NICHOLAS BERNOLD

Contents

Preface

BECKETT’S FRIENDSHIP 1979–1989

Preface

Max McGuinness

‘Abook is the product of another self than the one we display in our habits, in society, and in our vices.’ So wrote Marcel Proust inContre Sainte-Beuve, the name given to an unfinished critical essay-cum-novel that constitutes an early version ofÀ la recherche du temps perdu. Yet Proust’s social self has become so comprehensively identified with his book that the village of Illiers, where he spent summers as a boy, even took the step of officially transforming art into life, rebranding itself as Illiers-Combray in 1971 to mark the centenary of his birth.

This was three years after Roland Barthes published a brief essay proclaiming ‘the death of the author’, a nostrum that quickly acquired near-axiomatic status for a generation of literary theorists.1This was not exactly a new idea: T.S. Eliot had insisted just as forcefully that facts about an author’s life were of no direct relevance to our understanding of his work. However, in the wake of 1968 it was invested with a new political fervour as Michel Foucault, in his lecture ‘Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur?’, vowed an end to the ‘author concept’ for the sake of the ‘free circulation, free manipulation, free composition, decomposition, and recomposition of fiction’.2

Samuel Beckett was caught up in this debate from the off. Foucault opens his lecture with a quotation fromTexts for Nothing: ‘What matter who’s speaking’. (Ironically, this is attributed to Beckett himself, then at the height of his fame as an author, in the very year when he would be awarded the Nobel Prize, with no mention of the text in which it is found.) The choice can hardly have been accidental. There is probably no other author whose works lend themselves so readily to the kind of criticism Foucault is endorsing, for which expansive polysemy constitutes the guiding principle. And few have resisted the temptation to treat Beckett’s work as a literary Rorschach test.Waiting for Godotalone has,inter alia, been interpreted as an allegory for British colonialism in Ireland, for the author’s experiences in the French Resistance, for the Cold War and fear of nuclear holocaust, for the death of God, for the Second Coming, for Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, for Freud’s structural model of the psyche, for Jung’s theory of the self, and for Camus’ ideas about the absurdity of existence. A few years ago, I attended a talk following a performance of Peter Brook’s production of five short Beckett plays where two respected Beckett scholars immediately disagreed about whether Beckett was an ‘existentialist’ and the discussion pretty much failed to move on from there.

But at the very point when large sections of the academy resolved to do away with the author, the public became increasingly interested in these allegedly sepulchral figures (though not always in their inconveniently long and difficult books) – Illiers’ opportune hyphenation being symptomatic of an emerging global boom in literary tourism. (The local councillors responsible for this name change had perhaps not read as far asLe Temps retrouvéwhere Combray becomes the scene of heavy fighting, unlike their own pleasant little town, which is located over 100 kilometres south-west of Paris and thus remained far from the front line throughout the First World War.) Meanwhile, the love lives, feuds and bank accounts of living authors were regularly transformed into front-page news. Beckett, as André Bernold puts it here, became ‘the most watched silhouette on the boulevard Saint-Jacques’.

Not all of this was mere prurience. The latter part of the twentieth century, despite the rise of post-structuralism, was also a golden era for literary biography, which yielded, among others, Richard Ellmann’sJames JoyceandOscar Wilde, Claude Pichois and Jean Ziegler’sBaudelaire, Norman Sherry’sThe Life of Graham Greene, Graham Robb’sBalzac, R.F. Foster’sW.B. Yeats: A Life, and Jean-Yves Tadié’sMarcel Proust, not forgetting James Knowlson and Anthony Cronin’s biographies of Beckett. We thus know infinitely more about these writers than we did fifty or sixty years ago. This can but have an influence on how we approach their works.3Despite his deep sense of privacy, Beckett’s persona has been so widely written about that it has become unavoidably mixed up in our imagination with what Bernold calls his ‘creatures’. Whether or not Barthes and Foucault were right to dismiss the figure of the author, when confronted with Vladimir wincing or Krapp hunched over his tape recorder or Molloy resting on his bicycle, one’s mind always seems to turn to the ‘gentle mask’ placed over the ‘severe ossature’ immortalized in John Minihan’s photographs, surely among the most iconic images of the twentieth century. We simply cannot help it.

This is perhaps less true of other writers, even those whose lives have been similarly well documented. We can appreciateThe Waste Landwithout being irresistibly drawn to the prickly man behind it; we can puzzle over ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’ without being entranced by its fastidious creator; Bertolt Brecht’s indignities need not intrude upon our enjoyment ofThe Threepenny Opera. But the depth of Beckett’s personal kindness and humanity constantly seem to shine through his work.

Bernold records an occasion when Beckett’s German translator, Elmar Tophoven, noticed that someone was using a mirror to flash a beam of light into Beckett’s apartment. It transpired to be an inmate in neighbouring La Santé Prison who ‘was sending a signal to the free man opposite, the nondescript man, who, alone, would make sweeping semaphore gestures in return, which signified nothing save for: “Courage!”’ There, in microcosm, is Beckett’s perennial feeling of solidarity with the underdog, the intuitive sympathy for the outcast, which left over a thousand convicts in rapt silence during the 1957 production ofWaiting for Godotinside San Quentin Prison. And it reappears here in the closeness offered to an isolated young man, met randomly on the street, who was ‘unequal in everything, besides in affection’. Beckett even used to worry about whether his friend had a warm coat.

As Bernold admits, by themselves, facts about an author’s appearance or behaviour do not necessarily offer any particular insight into his writing:

There was in Beckett’s very appearance something like an undefined mute exclamation. Always verticality, the cliff face, the bird. Immersion in silence could become so deep that when one of us reverted to words he would take care to articulate them slowly, as if the other had become deaf. […] Perhaps this has no relation to this writer, one writer among so many others, that is not purely contingent and assuredly without significance for his work, or interest for anybody, unless linked to thisponderación misteriosais the event of friendship.

Ponderación misteriosa– the entry of God into a work of art, the moment, in other words, where the creator is juxtaposed with his creation. To what effect? What can the creator tell us about his creation that is not already there for all to see?

All friendship can offer is one potential point of entry into the hermeneutic circle. For it is through friendship that otherwise incidental details about a person are invested with meaning. In this way, over ten years of regular meetings, consisting of long silences punctuated with wry remarks, lovingly exchanged quotations and moments of exquisite tenderness, Bernold became increasingly attuned to the centrality of the voice in Beckett’s life and later work. ‘I have always written for a voice,’ he says during one of their meetings. And as the man’s physical powers faded, so his language became ever more refined and spare; the voice seems to be investing its final energies in a display of extreme concision before fading out for good. This comes across in the numerous pithy quips, infused with a distinctive Franco-Dublin irony, that peppered their conversations: ‘I will be there if they need obscurement’; ‘all my life, I’ve been banging on the same nail’; ‘put a bit of order in my confusion’; ‘getting down to insomnia’; ‘you’re looking surgical this morning’. It also emerges in Beckett’s rare comments about his work: ‘I’ll need some substantive-actors,’ he tells Bernold, who interprets this curious expression as being suggestive of a parallel between voice and movement in his final plays – each stripped back to its barest, most essential elements. ‘The immobile or almost immobile actor,’ writes Bernold, ‘is like a substantive forgotten in a big unfinished sentence.’ Both language and movement here approach a vanishing point – a fantasy of musical purity within nothingness that at once reflects the preoccupations of some of Beckett’s juvenilia and the perspective of an old man. ‘Things get simpler,’ he remarks to Bernold, ‘when the horizon shrinks.’

Becoming Beckett’s friend entailed challenges similar to those presented by his work. Like the audience members at the first production ofWaiting for Godot, many, on this evidence, would not have stuck around for the second act:

A card by return post gave day, time, and place for a meeting. This was the first interview; it lasts exactly one hour in near total silence. I don’t remember a single word. We sat opposite each other, royally mute. I believe I remember that we were hunched forward a bit, so as to examine the deep breathing of this silence.